The early mission and Reformed Theology of Charles Ringma

Charles Ringma’s formative Christian education was at Reformed Theological College, Geelong. Charles and Rita Ringma’s other educative process were in mission. When Charles had been appointed probationary minister at Broomehill, Western Australia, in 1967, there is a collision with what Reformed Theology taught and their spirit-inspired experience among the local peoples. It is the classical lesson in missiology. Formal theological categories are shaped in culture, whether in Niebuhr’s typology the Christ is below, aligned, or above. The idea of reformed Christianity is a reformation inside of western culture, and that is not necessarily a bad thing. What has been learnt in global Christianity over the past half century, and for Teen Challenge Inc., is not to be satisfied with the surface judgements, and to explore the cultural thinking much deeper.

Charles Ringma brought to the construction of an Australian experience of Teen Challenge Inc. an indigenous experience, while remaining outside the parochial bubble. The word ‘parochial’ is related to the idea of a church parish. The sad reputational history of local communities is about closemindedness. In Ringma’s leadership, there was the thinking and action whereby God Father, Jesus Christ, and the Holy Spirit, was not to be understood as closed inside any cultural paradigm. This was not, neither, a form of mysticism, although Charles was personally inspired by Christian mystics. Reformed theology could still speak truth, but not without a great scaling off its cultural pretence. This might not be enough for post-Christian readers of the history. Nevertheless, it was something wonderful, renewing, and Christlike. And for that Queensland society greatly benefited.

The Queensland movements of Charismatic Renewal (1967-1975)

Charles and Rita were among the younger generation, who in 1967, came into an experiential movement, known as the baptism with the Holy Spirit and the use of spiritual gifts (charismata). One of the movement’s important features was to transcend theological traditions. It is said that it first appeared among Anglicans in 1958, in places such as the United States and the United Kingdom. By 1962 it was recognised among the fellowships of Lutherans, and Presbyterians, and had reached both Methodist and Roman Catholic communities by 1970. The phenomenon would be widespread within the Christian world, but it had an older history which linked the American Holiness and Pentecost movements to the Apostolic tradition of the first century CE.

As a result of these types of charisma interdenominational links, Charles joined in with the Assemblies of God and became a denominational minister. Furthermore, there was a coalescing here with another denomination, the Methodist Church. It was the Methodist ministry, LifeLine, which first supported Charles’ vision of local street ministry in South Brisbane around 1968. This came about through personal friendship with the Rev. Ivan Alcorn, the Director of the LifeLine Office. LifeLine would fund Charles’ world tour in 1971 to produce a model organisation for drug rehabilitation, and the Methodists assisted Charles in the process of incorporating an independent para-church organisation in the following year. Teen Challenge Inc., in the early years, was very much a collaboration of Charismatic Christians belonging to the Assemblies of God and the Methodist denominations. The first Chairmanship (1971-1974) in the new Board of Management was Gerald Rowland, the leading evangelist in the Queensland Assemblies of God (AOG). The Chairmanship was passed onto the Rev. Wal Gregory, the Director of Methodist Department of Social Welfare & Pastoral Care and Chairman on the LifeLine Board of Management. The two leaders represented the two important nodes in the local charismatic movement, cojoining with the Catholic Church community in Bardon.

Figure 1. West End Methodist Church, circa 1900. Source: State Library of Queensland

Rowland was the minister at AOG Glad Tidings Tabernacle in ‘the Valley’ (Fortitude Valley), while Gregory was the minister at the Methodist Church at Kangaroo Point, ‘Wesley.’ When the Uniting Church in Australia was created – the cojoining of Methodist, Congregational and Presbyterian traditions – in 1977 the charisma collaboration was strengthened by formal organisations in each denomination, Methodist, Catholic, and the Neo-Pentecostal AOG. The term, ‘Neo-Pentecost’ is a reference to the third-wave charismatic or hypercharismatic movement, a descriptive qualification on the broader interdenominational phenomena. The difference is not a term of spirituality, there is the same gifts of the Holy Spirit, such as speaking in tongues and faith healing. The difference is one of history and organisational philosophy. In the Neo-Pentecostal thinking the Assemblies of God saw themselves as a postdenominational movement of the Holy Spirit. There was a blunt flaw in the thinking. The praxis did not sit well with the collaboration where organisational prejudice was form of blind sightedness. There could not be an acknowledgement of its negative corporatism – an aggressive action to build a movement into one corporate ‘body.’

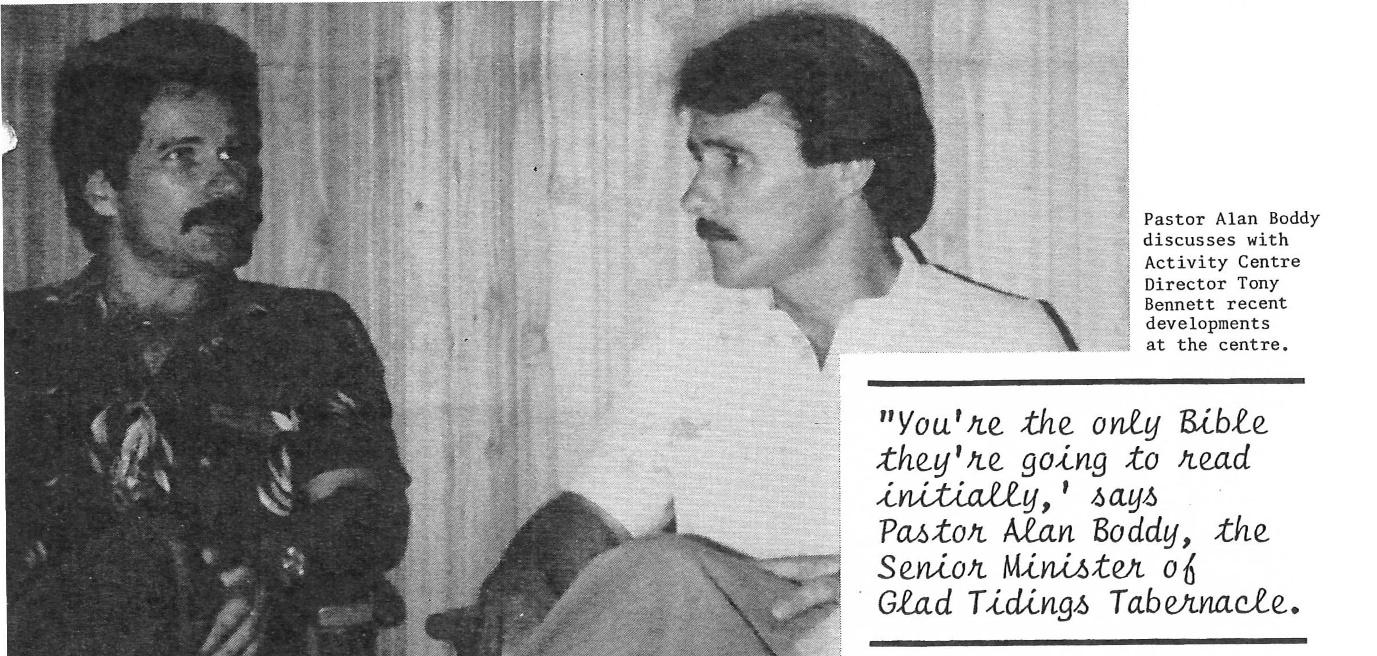

Figure 2. Teen Challenge Inc. Connection with Glad Tidings Tabernacle, 1984. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The word ‘corporate’ is related to the idea of a material body. In this case it was the Full Gospel Business Men’s Fellowship International (F.G.B.M.F.I). Spiritually, it was imaginatively the Body of Jesus Christ. The problem was its material intent. The organisation was founded in 1952 in Los Angeles by Demos Shakarian, and although ‘interdenominational’ as legal entity, in local practice, it has been the Assemblies of God which has formed the management of the organisation. AOG member Keith Kelly was Vice-Chairman of the Teen Challenge Inc. Board of Management and was Vice President of the F.G.B.M.F.I. Brisbane Chapter. Characteristically, a F.G.B.M.F.I. meeting was hypercharismatic in the worship hour rather than gentler Catholic and Methodist charisma form. Socially, the meetings were about business networking within the Neo-Pentecost frame. Although there is no necessary sharp distinction between interdenominational collaboration and postdenominational assimilation, there is, for the history, an acknowledgement of power plays or desire for firm control in the corporate, albeit without self-acknowledged intent (as it happened, i.e., pre-history judgement). Charles and Teen Challenge (TC) had good relations with the F.G.B.M.F.I. local chapters, and there were ‘TC’ speaking engagements among the Neo-Pentecostal businessmen. It explains why, during the executive directorship of Ringma, the Assemblies of God and its people would be so integrated with the ‘TC’ organisation. It was more than the fact that its global founder, David Wilkerson, was an Assemblies of God minister.

Teen Challenge in the early decade would greatly benefit from persons of other Christian traditions but it had an entangled relationship with the AOG’s Neo-Pentecostal traditional thinking. The TC Youth Activity Centre largely operated within the sphere of the Glad Tidings Tabernacle. Charles was an AOG minister, but he was grounded in the Reformed tradition, and was greatly influenced by the dissenting Christian traditions, Methodism and Mennonite most significantly. There was also the influence of the Anabaptist tradition through the relationship with the other Brisbane street mission workers, Dave, and Angie Andrews. By the 1990s the AOG local organisations were losing touch with the deeper Christian missions thought. The Neo-Pentecostal movement was captive to corporatism. Local AOG churches were rebranding and adopting an organisational restructure on the Megachurch model. Charisma was reduced to a movement of the corporation. Teen Challenge Inc. was working on a different model.

Jesus Revolution (1967-1971)

Incorporation of Teen Challenge was a means to an end, but it did not define the organisation. The different model was another movement, one which overlapped with the Charisma. The ‘Jesus Revolution’, or simply, the Jesus movement originated on the West Coast of the United States. The exact date is difficult since it was a series of spontaneous gatherings outside of any institutions (supposedly). It is said to begin in the Los Angeles or San Francisco areas, among those who were called, Jesus people, or Jesus freaks, originally young people looking for an escape from their drug habit. It was part of the mid-1960s turn to religion as a pop cultural phenomenon. The American West Coast was flooded with gurus of transcendental meditation, and soon joined by Christian evangelists, such as Arthur Blessitt.

Blessitt was an important archetype. He had been street preaching in Hollywood, California, with the reputation of being the “Minister of Sunset Strip.” The movement was more showbusiness than revolutionary. The revolutionary feature was the motifs of the youth counterculture in the German and French Romantic traditions: coffee shops of radical thought in seedily intercity districts of student habitations. In March 1968, Blessitt had opened a coffee house called ‘His Place’ in a rented building next door to a topless go-go club. Ann Wilkerson had much earlier organised the first coffee houses of the Teen Challenge movement.

Figure 3. Teen Challenge Inc.’s The Jesus Revolution Poster, circa 1972. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

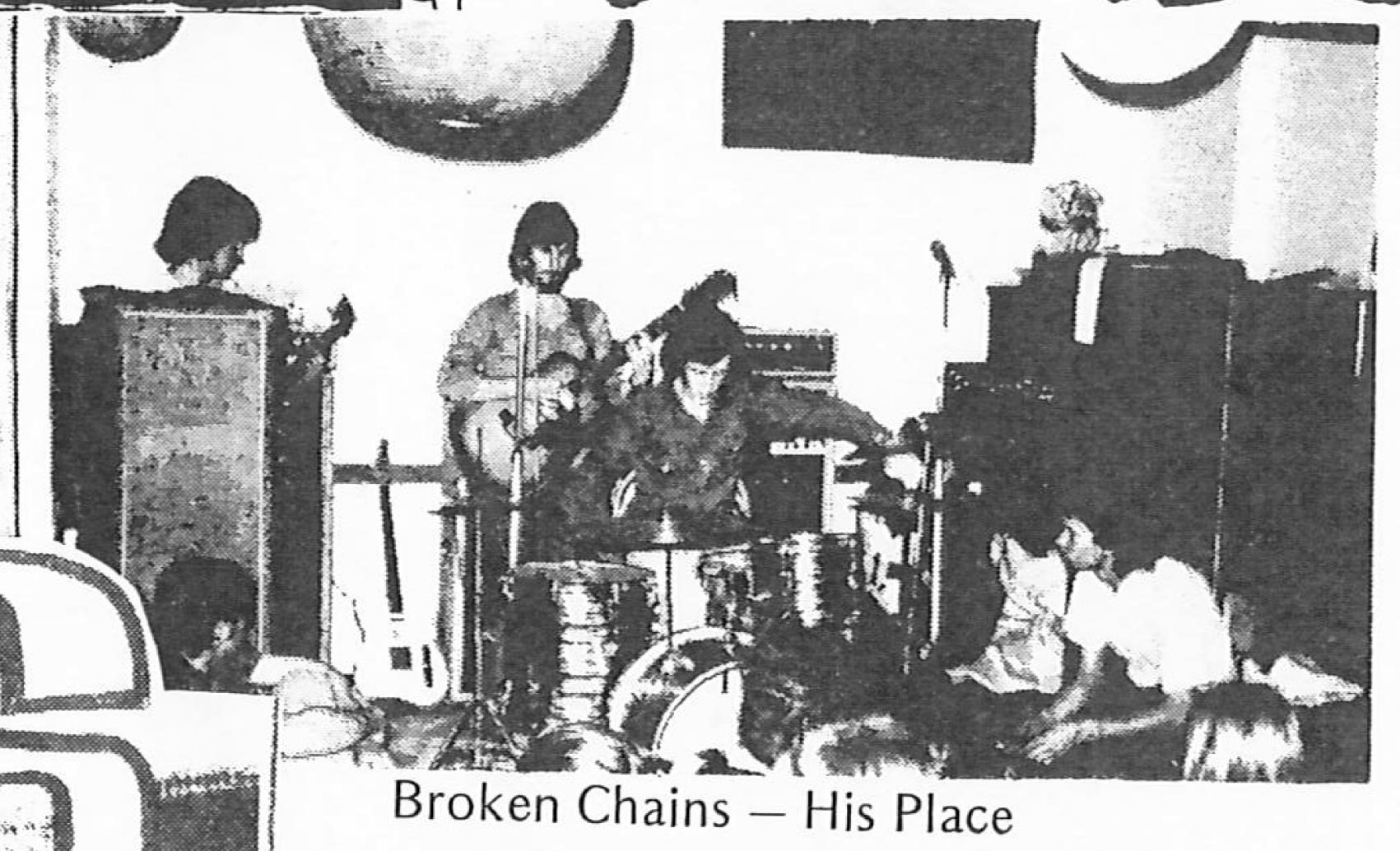

Teen Challenge, in Brisbane, would adopt the same motifs of the global Christian Coffee Shop Outreach, and spreading out to the campus and other counterculture sites, all in the first three years of the organisation. In only a few months of the formalisation, Charles Ringma, now Executive Director rather than a street worker, organised a small team to open ‘His Place’ Coffee House, 40 Elizabeth Street, Brisbane City. Its first director was Malcolm Cory (1971-1975). Terry Gatfield also quickly took on the coffee shop ministry directorship. In 1972 a second ministry was opened in the Turning Point Coffee House, Alfred Street, Fortitude Valley with TC workers, Peter Justice, Barry Bruton, and Rhonda Kretschmann. It was the rear basement of Glad Tidings Tabernacle. When Teen Challenge Inc. opened its head office, Enoggera Road, Red Hill, David Engwicht was the director of the coffee shop ministry, with Malcolm Cory taking the hands-on management at Elizabeth Street. In 1976 David Engwicht became Director of Evangelism, based at the Valley’s Turning Point Coffee House. By 1982 the facility became known as the Turning Point Coffee House and Teen Challenge Youth Activity Centre, with Derek Matthews, a theological student, as its chief counsellor. He was partnered with Carol Matthews, another Activity Centre counsellor. In 1984 Malcolm Cory took on the directorship of the coffee shop ministry based at the head office at 41 MacGregor Terrace, Bardon. By then ‘His Place’ had closed, the main work was the Turning Point Coffee House with workers, David Engwicht, Claire Fielding, and Alan Ruthford.

Figure 4. The Happening inside His Place Coffee House, with the Christian rock band, Broken Chains, performing, circa 1972. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

These types of ministry sites, called coffee houses, shops, or cafés spread across the local landscape, beyond the TC direct ministry, e.g., ‘Potter’s House’ in the Moorvale Shopping strip in suburban Moorooka. Again, para-church collaboration came to the fore, and TC persons were integrated into the mainly Methodist Church-run coffee ministries. The His Place Coffee Shop Ministry, though, was the main hub. Street evangelists would walk around the city blocks inviting young people, or anyone interested, to walk down to the Elisabeth Street basement. What they would find is an early 1970s mod décor lounge, a ‘uni students’ hangout, with a small kitchenette serving coffee and cinnamon toast, and sometimes with a folk or small rock band playing; the other new sub-cultural movement, Christian folk and rock music. A Jesus Music Festival was held on the 28 July 1972 at His Place Coffee Shop. The week earlier the Shop held screening of drug educational films (21 July 1972). A small bookshelf of Christian pop paperback books, yet another new sub-cultural movement, was placed in the corner. The conversations ‘hung’ around the recent trends in theology, politics, and sociology.

There were different audiences. Often Christian youth would come to simply to enjoy fellowship. The zealous among them were there to convert. The streetwise-but-unwise were curious, and they could be a mixed lot. Some were drug addicts who were looking for a way out of the ‘wayout’ experience. Others were simply impoverished by other means and were hoping for charity or their way out (more than charity). There were many opportunities for service, and it was delivered. An important means of delivery was in the LifeLine model. The Elizabeth Street basement was fitted with a 24-hour hotline and counselling facility. The service was an important means of practical help, whether furthering in friendly support of the coffee shop ministry, or the new drug rehabilitation ministry at The Way centre in South Brisbane.

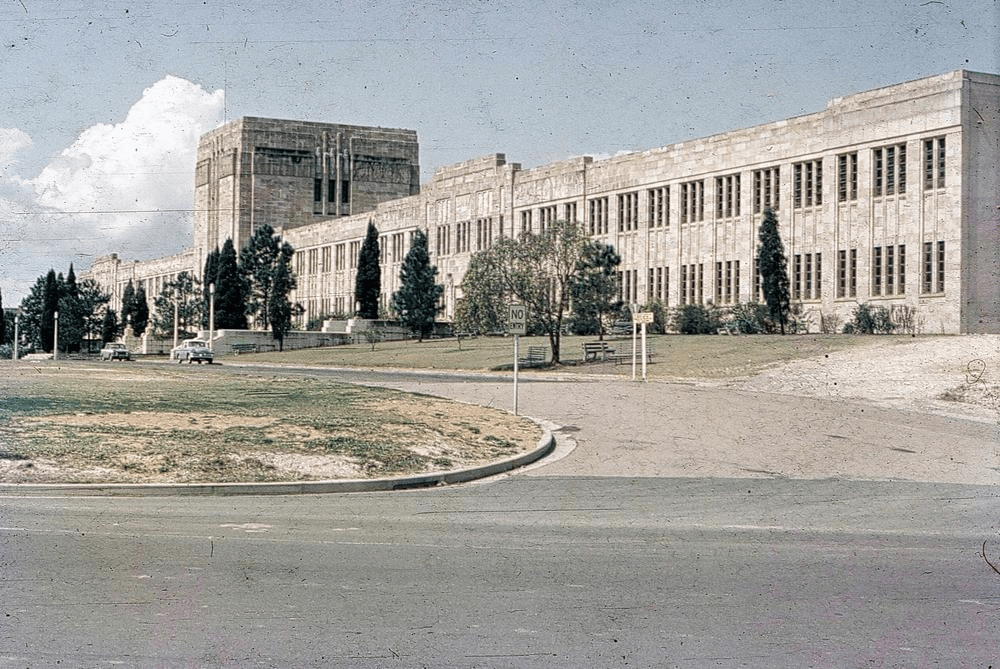

Figure 5. The Source of Teen Challenge Radicalism — The University of Queensland, circa 1963. Source: State Library of Queensland

The World of University Education

As a countercultural set of ministries, the early Teen Challenge organisation branched out onto the University of Queensland campus. A large portion of the first TC workers pool were students, across different fields, Engineering, Medicine, Social Work, and the Humanities, as well as learning for a few in the theological colleges. Sometimes it was a matter of gaining professional experience, other times it was a matter of Christian mission; the two were not exclusive. The first major step was the running of the Jesus Family Teach-In at the University (5-6 August 1972). These were the days before Charles involvement in university studies but there were a few older Christian university teachers who helped to make the campus links. Frank Anderson, the Old Testament scholar at the University was active in the Australian Fellowship of Evangelical Students (AFES), related to the British and American Inter-Varsity Christian Fellowship (IVCF). The IVF tradition tended to be apologetic-driven and connected many Teen Challenge persons with IVF authors, such as Os Guinness, and Francis and Edith Schaeffer at the L’Abri community in Huémoz-sur-Ollon, Switzerland.

The oldest campus group was Student Christian Movement (SCM). Theologically, it crossed the territory of liberal, radical, and left-wing evangelical Christianity. Teen Challenge enjoyed fleeting connections from personal friendships of SCM leaders, such as Ray Barraclough. The Newman Society represented Catholic interests, but it never had had a formative Charisma connection. Evangelical Union (EU) represented the interests of the Reformed, Anglican, or traditional biblical Christianity. It was an outgrowth of the Scripture Union organisation, a major in-school ministry for High School students in Queensland, and Australia. There were a few personable links with Evangelical Union, but the institutional mentality of conventional Evangelical Christians hit hard against those who had a counterculture ministry. Many EU students were anti-charismatic and militantly Reformed in their thinking.

“The Lay Institute For Evangelism (L.I.F.E., Sydney) for Campus Crusade for Christ” – in its long formal name – came to be the main vehicle for the campus linkage of Teen Challenge. The American organisation was founded by Bill Bright, famous or infamous for the tract publication, “The Four Spiritual Laws.” The organisation was well known for its large and small pop literature (tracts, booklets, manuals, and paperbacks) from Here’s Life Publishers in Santa Ana, California. In Queensland the organisation became known as Student Life, a sub-division of Life Ministries. The model was the American discipleship movement, informed by the host of American published paperbacks written on Christian discipleship in the 1970s (i.e., Johnny Ortiz’s Disciple, Robert E. Coleman’s The Master Plan of Evangelism, Watchman Nee’s The Normal Christian Worker), and American youth missionary organisations (i.e., Agape Force, Operation Mobilisation, Youth With A Mission). Neil Barringham, with partner Penny Barringham, was the Queensland Director of Student Life in the 1980s. Personal friendships among members of Student Life, and the other Christian Campus organisations, included the Barringhams and the Ringmas, forged new directions for Queensland evangelical organisations into social justice action and advocacy.

Figure 6. The ‘Four Spiritual Laws’ Type Coffee House, Teen Challenge. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

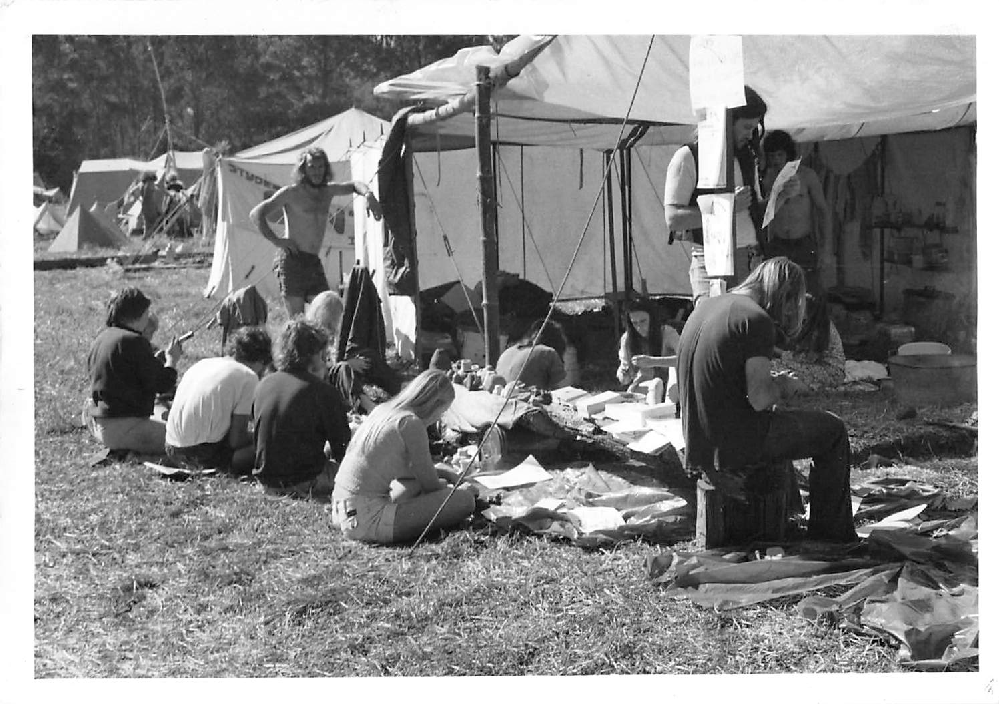

The author is privilege to be part of that second-generation of Teen Challenge work. However, the story needs to return to the first generation in the first half of the 1970s. The campus story and the world of university education is only one half. The other half goes back to the idea of a spontaneous ‘Jesus Revolution’. It was spontaneous in the tradition of American Folk music festivals, particularly Woodstock (15-18 August 1969) – mud and ‘the wayout’, but, behind the scenes, with massive organisation scrambling to keep on top. For Australia, it was the Nimbin Folk ‘Aquarius Festival’ in 1973. The counter-cultural arts and music festival had been organised by the Australian Union of Students, had been held three times (1967 Sydney, 1969 Melbourne, and 1971 Canberra). The theme of the Aquarius Festival was to celebrate alternative thinking and sustainable lifestyles and is considered the Australian version of Woodstock.

Figure 7. The House of Freedom at the Nimbin Folk ‘Aquarius Festival’ in 1973. Source: House of Freedom Archive

Teen Challenge fitted right in. In the 1970s the ‘Jesus Fish’ started to be used as an icon of modern Christianity, and it is said that the symbol and message was prominent at the 1973 Aquarius Rock Festival. It was the high point in the national Jesus youth movement. Much credit, though, goes to a sister organisation of Teen Challenge Inc. The House of Freedom was founded by Rev. Athol Gill, the New Testament lecturer at the Baptist Theological College of Queensland. His students want a practical dimension to his teachings on the commune ethos of the early Christian Church, first century CE. Its purpose was for the more seriously minded Evangelical youth to gather to discuss the interface between their Christian faith and the issues that were raised by the world in which they lived (i.e., Christian responses to militarism, poverty, racism, sexism, etc), and to follow in praxis. House of Freedom had first met as an organisation in the hall of the Jireh Baptist Church, Fortitude Valley, early in 1971. It happened at the same time as Teen Challenge’s beginnings. Many of the leaders and activists between the two organisations were known to each other as Christians deeply immersed in the counterculture. They participated in each other’s organised events. Loving friendships and companionships would grow and still exist to this day. Furthermore, the House of Freedom assisted Teen Challenge in developing a national profile. The Gill’s vision for the ‘Brisbane House’ was the same as the evangelist’s John Hirt’s House of the New World in Sydney and the House of the Gentle Bunyip, which Gill later founded in Melbourne. Eventually a national network of Christian community fellowships would be formed. The Ringmas and Teen Challenge shared in the same commune practices. And while the new Christian movements grew nationally, the members of ‘conventional’ local churches were being tested or being testy with their brethren, including those persons who dogmatically spoken in the good news of Jesus Christ.

A rupture broke out among Queensland Christian Churches in 1973. Teen Challenge and the House of Freedom was in the middle of it. The churches and parachurches had a decision. Retreat into fundamentalistic morality or embrace the progressivism of the Spirit. At first the Baptist Union retreated. It protested about the alleged nudity and smoking of marihuana and the use of public money through the Arts Council for the Festival of Aquarius at Nimbin. However, the other denominations with the help of the new Teen Challenge Inc. created their own solution to youth counter-culture celebrations. One of the first Christian music festivals in Queensland, came about when the Methodist Department of Christian Education (DCE), in conjunction with local television station Channel Seven, organised a 12-hour Christian Pop festival called “The Village Pop Revolution” at the Olympic Pool at Broadwater, Southport, in January 1971. The Methodist DCE Director, Rev. Lew Born, was a member of the Teen Challenge Council of Reference. The largest Christian music festival in Queensland, during this era, was the Warana Jesus Rock Festival in October 1972, organised by the House of Freedom in conjunction with the House of the New World and the Methodist DCE.

The Valley Festival, organised by the New South Wales Methodist DCE (Rev. Alan Walker), was said to be “Australia’s first Christian Pop Festival”, with 3,500 people over a long weekend, held at a site called Vision Valley outside of Sydney. The Baptist Union would soon join in, but not without the parochial battles far worse than what existed in the Methodist Church. The Union was hampered by a fundamentalist bastion and had been responsible for forcing Athol Gill out of its theological college and reassigned to the Methodist’s Alcorn College. The House of Freedom survived because of a bottom up-top down two-tiered system. The House of Freedom Inc. also had a ‘Board of Reference’ as Teen Challenge Inc. had its Council of Reference. In both cases the members of the Board were mixed in personality, education, worldview, and a division between honourable and dishonourable reputation from the perspective of history in the year 2021. The Board of Reference for the House of Freedom included Inspector J.H. Allsopp (educationalist), Rev. Ray Hunt (University Chaplain), Dr. L. G. Knott (consultant psychiatrist), Mr Kel Richards (radio personality), and Mr Keith Wright M.L.A. (then shadow Minister for Justice). The Board of Reference for Teen Challenge included:

- Felix Arnott, Anglican Archbishop of Brisbane

- Paul Wilson, Acting Head of Department in Anthropology and Sociology, University of Queensland

- Reg Leonard, Managing Director, Queensland Newspapers Pty. Ltd.

- Hadyn Sargent, local radio and television personality

- Phillis Cilento, famous-infamous medical practitioner

- Arthur Crawford, less-known medical practitioner

- Charles Noller, Director of Counselling for LifeLine

- Lew Born, Director, Methodist Department of Christian Education

- Gloster Udy, Theologian

The role for members of reference council or board was organisational guidance but, in a conservative society like Queensland of the 1970s, they were an asset in protecting the organisation from external attacks. Of course, the actions could go both ways and organisational directors and managers could be subject to internal criticisms by board members or governing counsellors. We, the general reader, may never know. No records have been kept of those confidential conversations, and formal directors and managers are generally too polite. The forthcoming book, however, might come up with details.

The Personal Retreat of the Camping Movement.

The events of Christian folk festivals and communes expressed an older theme of a larger history for Queensland and Australia, and indeed, the world: the Christian Camping movement. In the first three short years there were frequent and different types of camps which Teen Challenge organised. In the first year of full operation (1972) the target group were high school students as a drug prevention program. Teen Challenge worker Hans Booy organised the Jesus People Secondary School Camp, Caloundra (9-10 December). The following year saw evangelistic camps organised, the Jesus to the Surfies Witness Camps (called ‘Temporary Communes’) at the Gold Coast, on Bribie Island, the North Coast (now called, Sunshine Coast), and Cairns. Christmas-New Year family camps were also a regular feature in the Christian world. One of the first such camp organised by Teen Challenge was the Accent on Youth, 1973 Christmas Camp, at Beulah Heights on the North Coast.

Alcorn College is named after the Alcorn brothers, Cyril and Ivan, famous Methodist ministers. Rev. Ivan Alcorn was the Australian National President of Christian Endeavour in the 1940s. In 1949, Alcorn was appointed Queensland Director of the Methodist Young People’s Department (YPD). Under Alcorn’s directorship, the youth ministry of the Queensland Methodist Conference was revolutionised by building upon the emerging modern Methodist camping movement of the early twentieth century, and integrating new innovations, most of which had American origins. These strategies and tactics combined with the older tradition, of the British Australian Keswick movement which were the heir of the Holiness movement. The purpose and outlook of the Tamborine missionary combined camp sites, close to Brisbane, are part of this ethos. It was the American Keswick movement which had originated the “The Four Spiritual Laws.”

Alcorn had brought an American-style entrepreneurial spirit to the YPD. He was described by his wife, Iris Alcorn, as having the personality of an innovating salesman who was always looking for money-making schemes. It was not necessarily a bad trait. Camping, communes, and shared housing projects can be expensive. The two-tier system brought challenges, problems, as well as opportunities and pragmatic solutions for Teen Challenge Inc. There were members and leaders like Ivan Alcorn who could govern well in the corporate sense, a top-down process. It did not necessarily discount the bottom-up, but populism brings unfortunate tension in the uneducated state.

Concluding Remarks

All these comments bring the reader finally to understanding the first Teen Challenge Inc. Board of Management. The Council of Reference was a separate body for guidance and for corporate credibility and ceased function around 1975. The Board was the governing body, and it was made up, between 1972-1974, of Gerald Rowlands, Charles Ringma, Wal Gregory, Keith Kelly, Ralph Read, Harvey Pollock, Ted Watson, Henry Baskerville, and Don Usher.

Several members have been introduced in the essay: Charles Ringma was the Board’s Secretary & Executive Director; Gerald Rowlands, the Chairman and Pastor of Glad Tidings Tabernacle; Keith Kelly, Vice-Chairman and F.G.B.M.F.I. Brisbane Chapter Vice President; Wal Gregory, the Director of Methodist Department of Social Welfare and Pastoral Care; Chairman, as well as a member of the LifeLine Board of Management. The other members were no less important: Henry Baskerville, who was the Board Treasurer and the state Vice President of Gideons, as well as the Manager at Newmarket Commonwealth Bank; Ralph Read, General Superintendent, Assemblies of God Australia; Harvey Pollock, Presbyterian Minister; Ted Watson, Church of Christ Minister; and Don Usher, a chartered accountant.

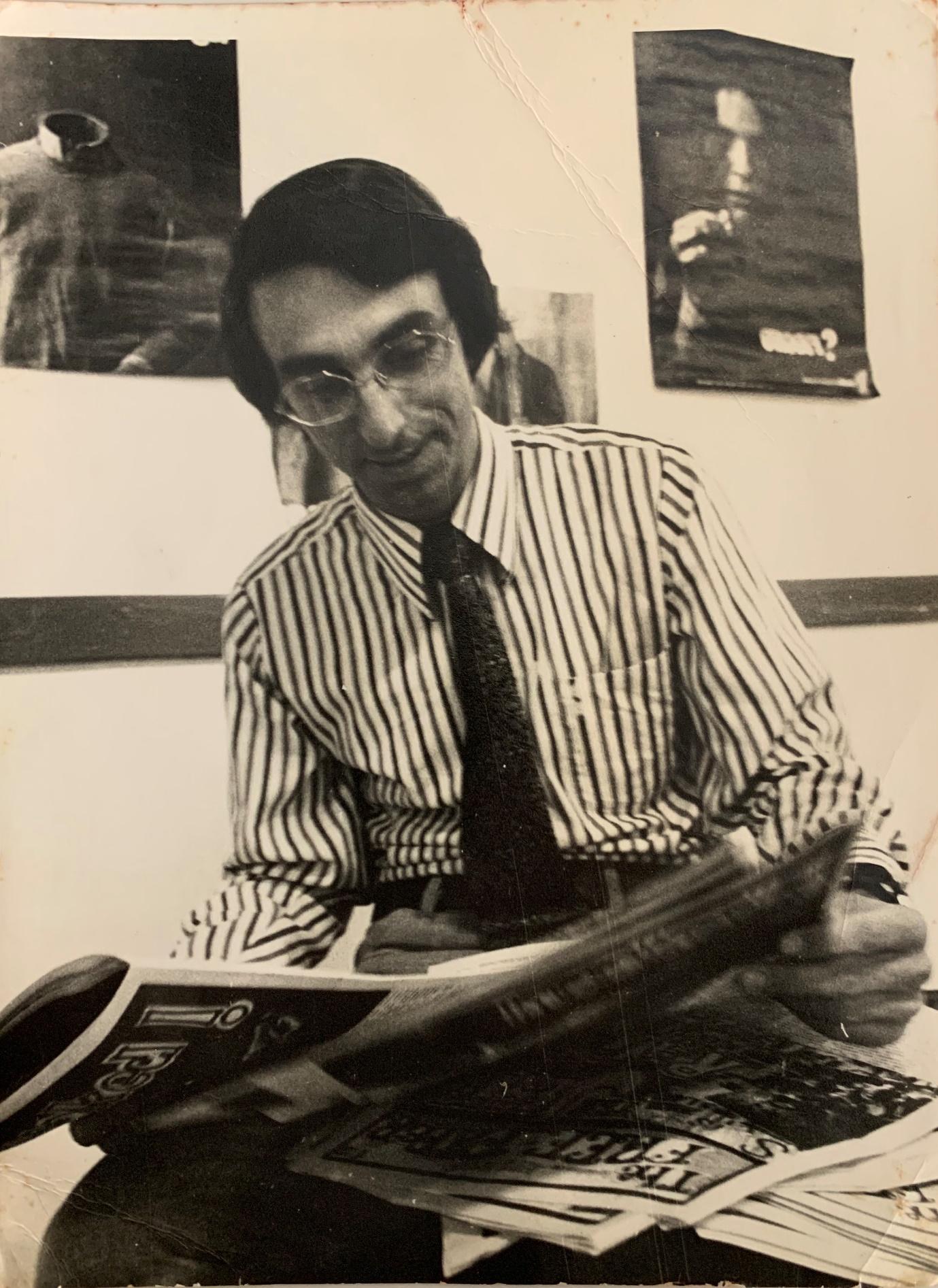

Figure 8. Charles Ringma at work in the Early Days. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Figure 9. Chairman of the first Board of Management, Teen Challenge Inc., Gerald Rowland. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The perspective here is top down, but that is no less or no more than the bottom-up perspective which has also been described in the essay. Teen Challenge Inc. is the work of the Holy Spirit, but that does not mean it is spontaneous and nor does it necessarily mean it is providential. The reader of today’s history must ask themselves what does ‘the past’ mean? Thinking about any past we see that there is always something that comes before, even ‘before’ an origin; Christians believe in an eternal God. With links with what comes before, there is no true spontaneity. There is a pattern to history, even though people cannot agree to what the pattern is. Without any such schema, there is no history. In our contemporary times, few historians believe in a straight linear timeline as a sufficient pattern. We may not be able to go back in time, we might only go forward in time, but this contested view is not the issue. Philosophers of history have argued that in any given moment, or in any given event, there are multiple actions, and thoughts at different layers: global, national, regional, and local. We now realise that we live in a networked universe, and, as the Holy Spirit, maybe we have always lived in a networked universe. Whether providential or imaginatively constructed, the point is that, as we read the history of Teen Challenge Inc. there needs not be great concern about ‘going up’ or ‘going down’. Scales are mere measurements. In the language of 1968, the better perspective is that we are spirit persons ‘hanging together.’