Spirituality and Queensland Society

The problem with an especially uneducated reader who is unfamiliar with these terms of the humanities and the social sciences, is that they think the author is saying something false because of the constructivist view of history (the historiography). So, let’s put all our “cards on the table.” What is not constructed in thought? Nothing can only be the true answer. Theology is constructed, and faith without theology can speak not a single word. To bastardise Wittgenstein, “if you cannot express your mysteries into communicable words than you are not in the game of telling the story.” That might seem unkind, but we have been living in a modern world where nonsense has greatly increased, and the power of education has eroded. Jesus wants to save us all from fundamentalist belief (of any type). Such dogmatic belief is the antithesis of faith. It is hoped that the essays have been pushing the level of reading common for most, somewhat further – a rethink at an undergraduate level for most students in the humanities and social sciences. This is particularly important for Queensland readers of the Queensland story, for populist gossips would have it that we are all bunch of ‘dumb-asses’ who no love of serious literature.

Gossip, memes, reference to mere memory, do not come close to capturing the spirit of what needs to be said.

Spirituality cannot be captivity or expressed in dogma, indeed, the Holy Spirit does not reside in any dogmatism. Fundamentalism has eroded at Christian education, and, unfortunately, that included education in and around Teen Challenge Inc., albeit against the best efforts of the educators. The next essay will explore Teen Challenge’s education in and of spirituality.

That spirituality began in 1972 with the common touch, with Charles & Rita’s North Queensland Tour (Cairns, Karanda). Mixing it up with a wide range of personalities, landscapes, and lifestyles. However, it does not finish with the common touch. It always finishes with an extraordinary touch of Jesus Christ, the touch in which the institutional Church resists.

Social Justice

What makes the spiritual touch of Jesus Christ extraordinary is the understanding of social justice. In the late 1980s Teen Challenge Social Workers, led by Ian Goodson, working in the Teen Challenge Inc. Head Office, this time at 41 MacGregor Terrace, Bardon (QLD 4065), are envisioning the social ethos of the previous years in Teen Challenge.

By 1991 Charles is the part-time senior research assistant in the Department of Social Work and Social Policy, The University of Queensland. Charles Ringma developed a history of Australian Disability Policy and Legislation and a history of the Development of non-Government Disability Services in Australia. It involved evaluation and write-up of a New Disability Services Program for physically disabled persons (Catholic Social Welfare), as well as an analysis and write-up of a Consumer Study on Services for the Disabled in Queensland, and an evaluation of a new independent living service for intellectually disabled consumers (Community Living Program).

The equivalent large study of the ‘Alcohol and Other Drugs’ (AOD) area and Teen Challenge still waits investigation. The challenge is often that the social history has to be completed first.

Civil Disobedience, and State Corruption

From the essays we see that social justice of Teen Challenge was bigger than the AOD area. It involved civil disobedience and challenges to state corruption was at the fore. John Robertson, as the solicitor contracted by Teen Challenge Inc., did what could be done within the existing laws to protect clients.

However, in 1977, it required more, and Charles Ringma, among a minority in the Church leadership, participated in the Right-to-March Street March, and was subjected to controversy in the midst of Police Violence and the National Party’s anti-democratic strategies. Charles Ringma and Noel Preston, as reported in the Courier Mail, from the Press Conference (25 October), among 16 Church leaders on the Right to March as a democratic right.

Religious Politics of Christian New Left

Contrary to the unthinking and conventional pew-seaters, politics is inescapable to being a Christian, in a world devoid of the compassion and kindness of Jesus. What is worse for conventional thinking is that ideological framing comes into play. The essays have been sketches with regard to the global response of the Christian New Left to the brutal ‘neo-con’ (neo-conservatism) masquerading as Christian realism. The Neo-Orthodox Niebuhrs most likely did not intend the type of the cultural centeredness expressed in the writings of William F. Buckley, but American realism of the mid-century grew into something very ugly: – the cultural legitimisation for wars, climaxing in the American staging among the Vietnamese civil wars. Much of the evangelical left or left-of-centre in the 1970s were overshadowed by the neo-con backlash of the 1980s with the ideas that wars of liberation could never be a mistake, and countries of western European heritage were Christian nations which had to be defended to the last man (gender specific).

Organisational Issues of National Profiling and Media, and Resourcing

National Profiling

The point has already been made in the last essay, that Australian organisations do not do federation well. State revelries tend to make organisations inward looking to local and regional concerns, disconnected to the national and global perspectives. Too little is understood of operations in New South Wales, Victoria, and South Australia.

Media from What it Was

The previous essay began a consideration of Teen Challenge media. In the early days it was possible for mass communications in personable presence. In 1972 John Healey gave an ‘Occult Talk’ in front of 1,000 students at Kelvin Grove High School, Victoria Park Road, Kelvin Grove, (QLD 4059).

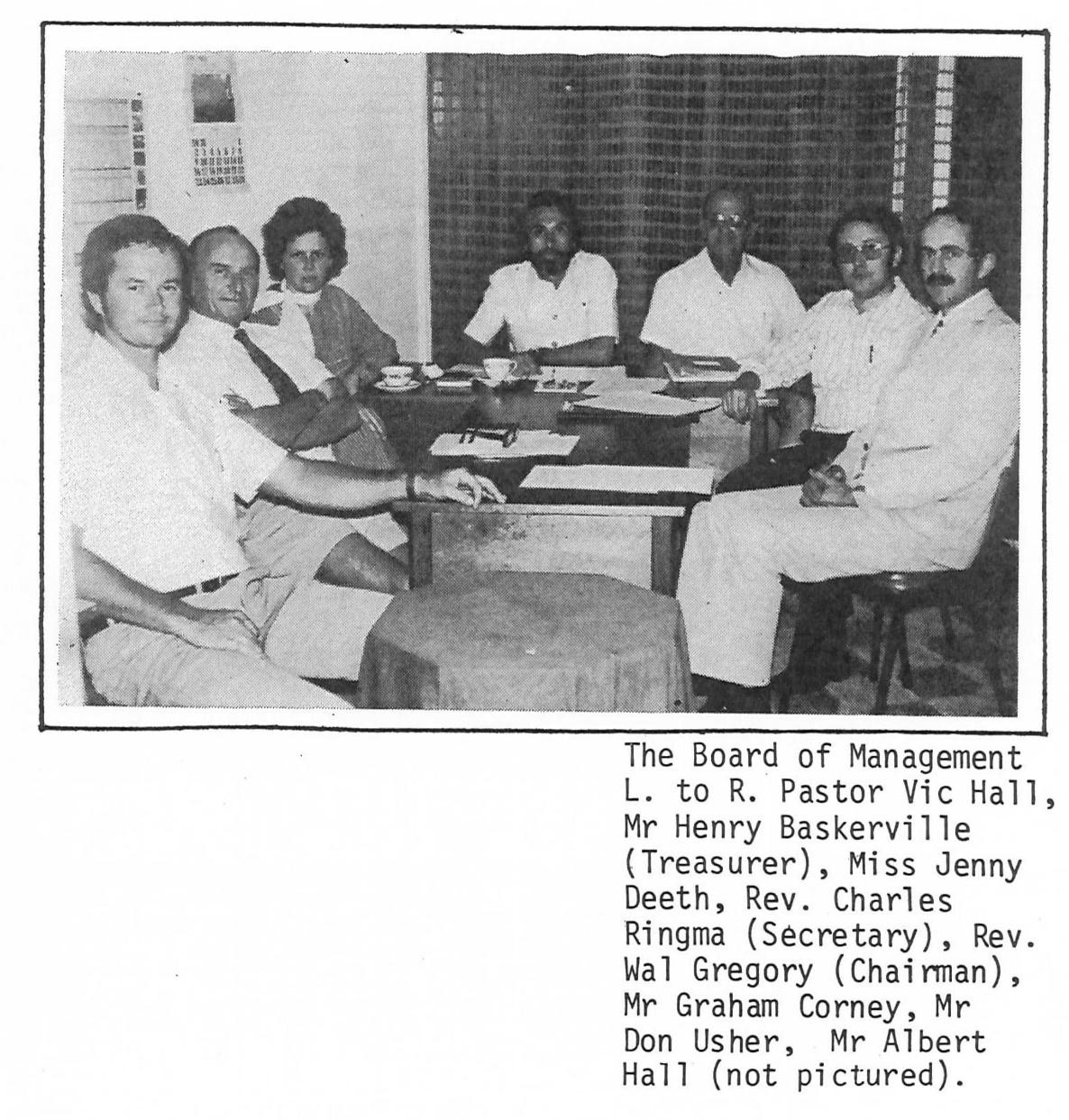

Figure 1. One of the Teen Challenge Board of Management, circa 1977. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The heyday for Teen Challenge media was to establish a permanent and long-running Teen Challenge Times (G.P.O. Box 2086, Brisbane QLD 4001). Chris Adams was the Editor. The Contributing Editors were Ian Thomson, Geoff Dean, Eddie Blaiklock, Denis Smith, and Bob Adsett who also responsible for the layout and design. During these years Chris Adams was holding broadcast sessions as the 4BC Sunday Night Radio Program.

Formal Openings, Dedications, and Launches

By the last 1980s periodicals and radio broadcasts were thinning out. Formal openings, dedications, and launches during the decade helped to keep promotion of Teen Challenge going. For example, the opening of the Lady Musgrave Home for Girls (14 November 1987), 31 Simpsons Road, Bardon (QLD 4065). In two weeks after that event Joh Bjelke-Petersen would reign as Premier and head of the Nationalists. There is no casual connection but an indication of the risk of any political association in such promotion. In these later years of the collapse of the Nationalist vote, was a false perception that Teen Challenge Inc. and other evangelical-orientated organisations were allies of the failing Nationalist government. The Queensland Minister for Welfare and Family Service, Yvonne Chapman, opened the Lady Musgrave Home for Girls. Her policies were not popular with the social work profession, including Teen Challenge Inc. The policies were the last reactionary gasp of conservative government which still believed in the rigid moralistic framework of the century previous.

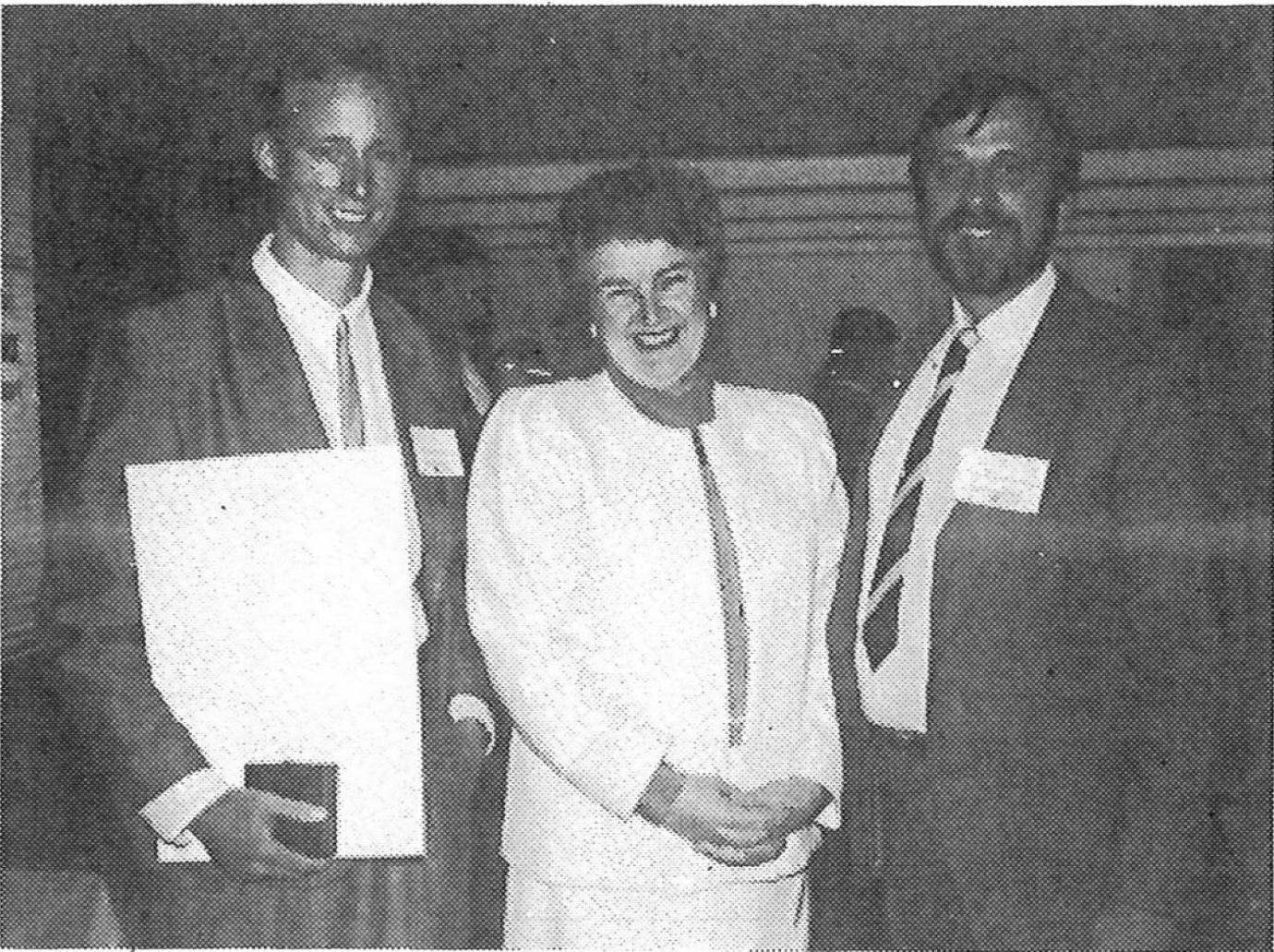

Figure 2. Queensland Award for Youth Achievement, presented by Yvonne Chapman MP, with Alex and Claude, 1987. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

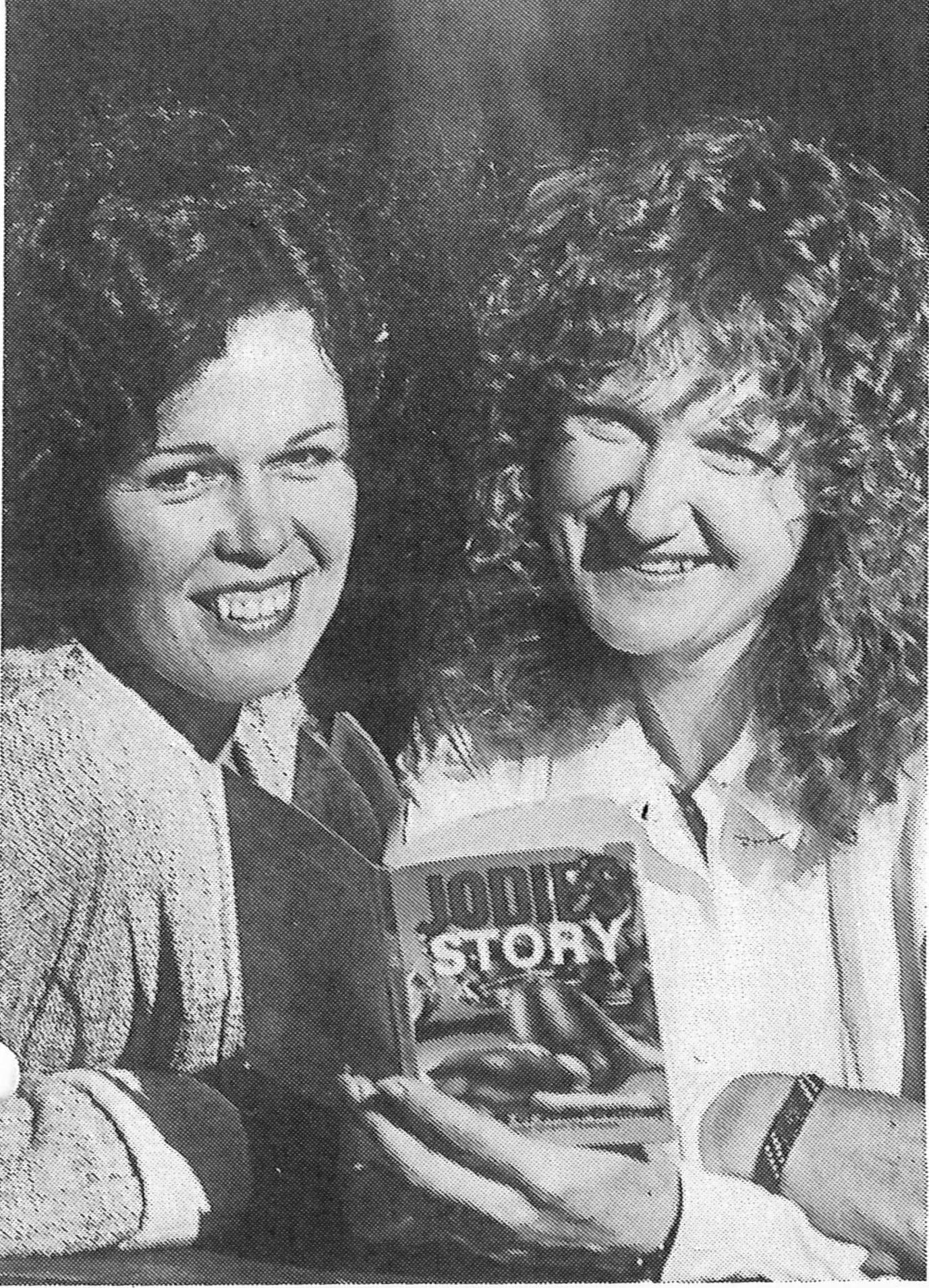

Such policies contrasted with the 1991 book of Jeanette Grant-Thomson, Jodie’s Story: The Life of Jodie Cadman. It was a history from below of a Teen Challenge convert.

Figure 3. The Launch of Jodie’s Story, Jeanette Grant-Thompson and Jodie, 1991. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Corporate and Public Fundraising.

In the 1980s and 1990s a pathway was forged in Teen Challenge’s Corporate and Public Fundraising.

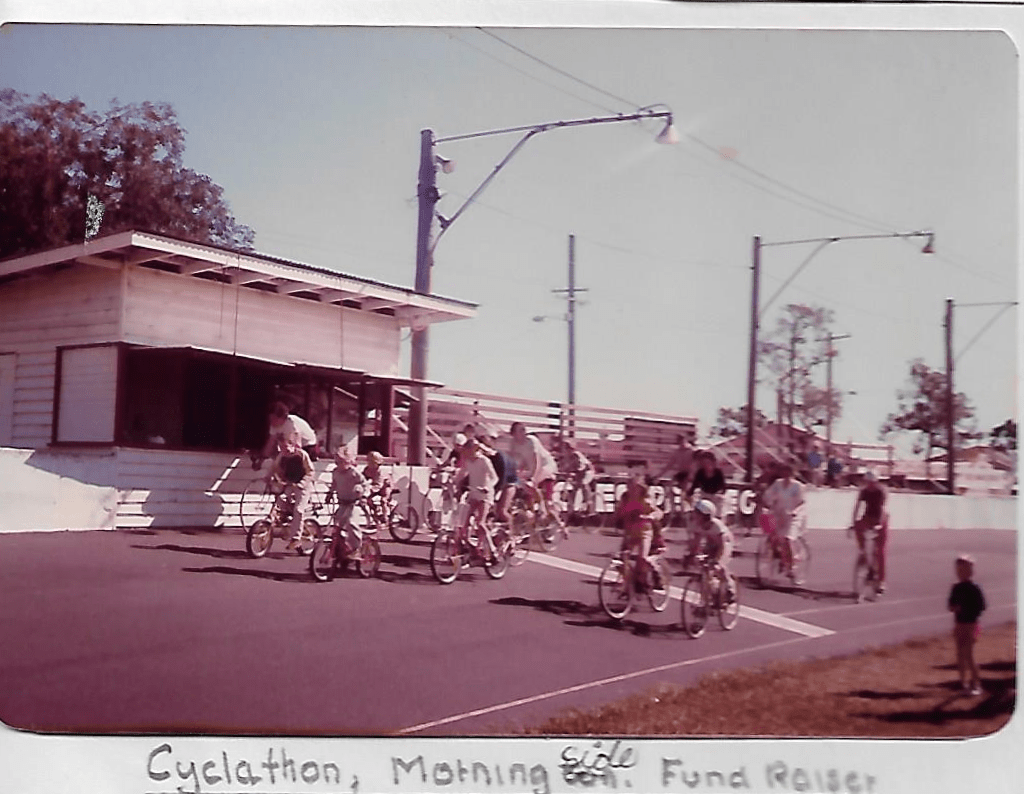

Its beginning appears to be the Teen Challenge Cyclathon, on 19 November 1983, at the Hawthorne Park Velodrome, Hawthorne QLD 4171. Around the same time, the local Channel Seven celebrity, Mike Higgins, was appointed the Patron of Teen Challenge Inc. The exercise of having a high-profile patron did not outlast the decade. There were other major fundraising events as the cycling events in different circuits became an annual happening. There was also the Peters Billa Bong Fun Run. In 1992 Jim Coward became the Director, Public Relations and Fund Raising, working at the Teen Challenge Inc. Head Office, 400 Wickham Street, Fortitude Valley (QLD 4006).

Figure 4 The First Teen Challenge Cyclathon. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Respite: Spirituality

The concept of respite was always important in Teen Challenge Inc., and the theme was introduced in the previous essay. Here the theme is developed.

Teen Challenge Bookshop

Popular texts on spirituality were purchased from the Teen Challenge bookshop in Newmarket, and it happened in the days of the first wave of Christian retail shops in Brisbane. Book reading for many Christians is a form of respite, rather than a study. It is a time for quiet reflection and inspiration.

Figure 5. Teen Challenge Bookshop, Newmarket, circa 1978. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Farms and Camps outside of the Urban Setting

The formal part of respite in Teen Challenge was the farm in Laidley (QLD 4341) with Steve Jeanerret as the Farm Manager, and the farm at Palen Creek, (QLD 4287; referred to as the (Rathdowney farm in the records?) with Farm Managers Hilkka and Perry McKenzie.

Figure 6. A Teen Challenge Farm Camp Out with Peter Wilson, circa 1978. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Craft and Pottery Studio

Led by Rita Ringma, Teen Challenge artists practice spiritual respite. Her Craft and Pottery Studio was a centre of calm creativity.

Spiritual Healing and Spiritual Retreat

Camps were annual time for respite for the whole organisation. Memories would differ as to Teen Challenge camps as special time for respite and spiritual renewal. Among the records attention was drawn to:

- Teen Challenge Staff Volunteer and Family Camp (4-6 December 1987), Kenilworth Homestead, Kenilworth (QLD 4574) with guest speaker, Noel Gibson;

- 1982 Teen Challenge and Jubilee Fellowship Camp, with speaker Greg Passmore, Neranwood Conference Centre, with guest speaker, Greg Passmore;

- Teen Challenge Camp (28-30 May 1982), Burleigh Heads Convention Centre, Burleigh Heads (QLD 4220); and

- Teen Challenge Training Camp (21-23 November 1986), Kenilworth Homestead, Kenilworth (QLD 4574), with guest speaker, Gordon Broussard.

Retreats have a double-edge spirituality. There is the respite from ordinary pressures and the humdrum, but the return from the ‘mountain top’ experience can be painful. The experience reflects the gap in a too simplistic binary of the sacred and the profane.

Education in the ‘Institute in Basic Youth Conflicts’ Public Seminars, and the Teen Challenge Training Institute

The other hand to spirituality is education. What good is spirituality if the person is not learning?

Drug Prevention Program (Schools and Churches)

The longer educative program in Teen Challenge Inc. is the drug prevention programs at schools and churches. Most of these records have been lost and so it is certain as to the regularity of the program.

Teen Challenge Training Institute

The later and larger, formal program was the Teen Challenge Training Institute. There is no definitive record of the graduates, but from other records we have these 1981 names of graduates:

- Sue Ball.

- Roger Clarke.

- Neil Earl.

- Sandra Eyles.

- Warren Hodgson.

- Tracey Pryor.

- Wayne Talbot.

- Robin Turner.

The staff of the TCTI shifted their work among the roles of Director and Senior Resource Officer – Brendan Scarce; Deans – Neil Paulsen; Training Coordinator – Craig Furneaux; School Administrator – Debbie Peters; and Trainers, Mike Power and Pym Kuipers. There was also Ian Goodson as Course Director, Careline, and Charles Ringma as a clinical teacher. The course was made up several seminars, some which were stand-alone and open to the public with priority for course students. Among those seminars recorded were:

- Gympie Youth Workers Training Seminar (26-27 August 1988), Gympie;

- Teen Challenge Training Institute Winter School (23 June-3 July 1992);

- Teen Challenge Training Institute Summer School (30 November-11 December 1992)

- Teen Challenge Training Institute Seminar (21-22 February 1992);

- Teen Challenge Training Institute Seminar (4 April 1992);

- Teen Challenge Training Institute Seminar (2 May 1992);

- Teen Challenge Training Institute Seminar (13 June 1992); and

- Teen Challenge Training Institute Seminar (7-8 August 1992).

The TCTI seminar organiser was Kevin Ryan. Among the stand-alone public seminars were:

- Teen Challenge Seminar on Homosexuality (15 May 1982), Bardon Professional Centre, Bardon (QLD 4065) with speakers, Charles Ringma, Peter Lane, Mary Santillon, and Ted Watson;

- Sexuality and Today’s Christian Seminar (30 October 1982), with speakers, Peter Lane, Pat Noller, Ted Watson, and Charles Ringma;

- Outreach to Troubled Youth Seminar, Bardon Professional Development Centre (22-23 July 1983), organised by Claude Boulenaz;

- 4th World Seminar (10 May 1986), Christian Community Church, 1148 Gold Coast Highway, Palm Beach (QLD 4221), organised by Colin Foote;

- 4th World Seminar (12 July 1986), Brisbane City Mission, Cnr Warner & Ann Street, Fortitude Valley (QLD 4006), organised by Claude Boulenaz;

- 4th World Seminar (8 August 1987), Glad Tidings Tabernacle, Barry Parade, Fortitude Valley (QLD 4006), organised by Claude Boulenaz and with keynote address by Charles Ringma;

- Crying on the Inside Seminar (8 July 1991), Queensland Development Centre, 59 Costin Street, Fortitude Valley (QLD 4006) with speakers, Raymond Brock Chris Cantor, and Pierre Baume; and

- Teen Challenge Parenting Seminar (19 August 1993), Sheraton Hotel, Turbot Street, Brisbane (QLD 4001), coordinated by Alec Spencer, and hosted by Wayne Alcorn, National Director Youth Alive, with speakers, Margaret Bunker, Mike London, Rama Spencer, Denis O’Brien, Paul Squassoni, Claude Boulenaz, and Bob Engwicht.

Figure 7. AOG Pastor and Teen Challenge Worker, Wayne Alcorn. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The book will explore the pedagogies of these educative events, where there will be an uncomfortable discussion between the ideology and the critical thinking scholarship. Other similar events outside of Teen Challenge Inc. formal sphere were also happening. When Peter Lane left the work of Teen Challenge Inc. behind, he developed his own Liberty Ministry, not formally recognised by Teen Challenge, and become the Director of Exodus South Pacific. Lane was involved in the organisation of the National Conference of Christian Ministries to the Homosexual (26-27 October 1990), Brisbane Life Centre, Munro Street, Auchenflower (QLD 4066).

Concluding Remarks

Queensland Pedagogies (and research).

In contrast to the hypo-conservative reactionary thinking, Brisbane and Queensland were experiencing a Christian scholarly renaissance, with several different writers, but formidably with two of the earliest evangelical street workers, Charles Ringma and Dave Andrews. Charles Ringma was named a joint winner of the 1995 Australian Christian Book of the Year Award presented by the Australian Christian Literature society for the book, Catch the Wind. In the last three decades, Ringma and Andrews have been the country’s prolific producers of paperbacks on Christian faith, social justice, and flourishing, institutionally-unbounded, spirituality.

Christians can often have funny ideas about spirituality, which do not accord with the critical thinking reading of scripture, tradition, and insight from knowledge depositories. The flawed view is prejudicial, believing that the spirit or the sacred has nothing do with secularity which too easily described as vulgar. The history of Teen Challenge Inc. has shown differently.