The last set of essays brings the narrative closer into a set of analytical histories. Greater empirical work is left for the parallel book chapters. What is being attempted at this point of the drafting are summaries from the unfolding of the previous essays for the keener of mind. The chapters of the book will elaborate further, with the assistance of the reader, where it is hoped that the reader will provide the author feedback which will be developed into the book.

Since readers need not be familiar with the art of history writing and the construction of historical narrative, some small insight into the historiography needs to be presented. The Rankean School of History and the British Empirical School tended to become over-obsessive with details in creating the narrative. Any true and accurate well-read story cannot be over-burdened with details of events and every fine factor. It is not that accuracy in details and facts are not important, but they cannot drive the narrative if understanding is to be possible. Theoretical frameworks are what drives the narratives, while remaining true to empirical observations, as much as observations are a matter of different perspectives. That historiography is a statement of both the science and art of history.

The History Wars, in Australia and globally, has done great damage to person’s perceptions of the history profession and what is history. Great stupidity has arisen from cultural warriors hellbent to destroy one school or another for political gain. Peter Ryan’s History War casted upon the reputation of Manning Clark in 1993, and it opened the door to John Howard’s Cultural-War, and confusion and chaos reigned upon the land. Several Australian historians have been repairing the damaged caused in the last twenty years, but the recovery will take time. This is the Challenge of the historian writing the history of Teen Challenge Inc. Organisations have missions, the purpose of its existence, and in that there is stability, but in how the mission is understood always come great change. Persons do not deal with change as well as their think. There are cognitive anchors in the familiar and memory shines a comfortable tale, and in doing so, it is less than the truth of the past. Australian social historians, such as Manning Clark, were misunderstood, and the imperfect grand storyteller more so. He was a great disruptor to the school histories taught from the 1930s to the 1970s, even as he imperfectly thought out the histories from the influences of those schools.

The historian, if honesty and truth is highly valued, has to be a disrupter to the groupthink. Knowledge is power and here, as the history of Teen Challenge Inc. it has to be used wisely.

Recognition in the 1980s Neo-Conservative Society

Between the radicalism of the 1970s and the full-blown neo-conservativism of the 1990s, the decade of the 1980s was simply conservative with the creeping neo-conservative way of thinking and its schemes. To explain. Radicalism can mean different sets of beliefs but in Christian Thought it has the distinct framing of The Way, or the spirit/ethos/ethics of Jesus of Nazarene. This is the Jesus who is outside the institutional system. He is the prophetical Son of God, sometimes condemning worldly ways, sometimes weeping for those of the world, sometimes shaking the dust from his sandals and walking away from the world. Camus’ The Outsider (1942) or L’Étranger. There is here a love for the outcast, not the pew-sitter.

Conservatism, broadly speaking, is the conventional attitude. It is the general attitude of the shallow thinker (exceptions in the intellectual variant unrelated to the common), who cares little for education, except training for ambition, and who is obedient for success. It is the conservation of obeying your parents, obeying church leaders, and obeying all in authority…religiously. As ethical judgement, the thinking can be neither good or bad, and it can be both good and bad, and that can be teased out. The judgement is contextual with questions of the harm done, fairness and human flourishing.

Neo-Conservatism is something different and it is contentious whether it is really conservative in its stance. From a slight position to the extremes, the ideological outlook is reactionary. The positioning is certainly not Burkean conservatism where Edmund Burke’s principles made room for revolutionary thinking, but with a heavy dose of caution and moderation. This thinking is not reflected in William F. Buckley’s writings, even as the prose comes heavily with friendly and polite reasoning. In neo-conservatism, the capacity for compromising moderation is replaced by binary thinking, the forces of good and evil, whereby civil rights legislation, argued by Buckley, had the appearance of the good, but therein lurked the evil. Buckley’s primary positioning was a militant defence of the American South as the pure stable state, as the mythologies of the South would have it. ‘The North’ was always the greatest threat (a motif in The Witcher series). Civil rights were a Trojan horse to dismantle the South and its culture.

The American South wanted to religiously continue its separation and isolation. What has this to do with Australia? The same structure of the debates, with different geography, was happening in the 1980s Australian society. There were arguments of distinct cultures and ways of life in the federation. Queensland was unique, so was Northern Territory, Western Australia, Tasmania, and so forth. We debated the politics of the Deep North, the Southern States, and Tasmania and South Australia were generally ignored, and Western Australia always feel that it was a different country to the rest of the nation. It was not only the Blainey’s ‘tyranny of distance’, but it was also the politics of Canberra and of each capital city. It had always been this way and continued to be so, however, the 1980s saw the greater militancy as the last decade of the Joh Bjelke-Petersen Government against the Federal progressivist Labor Government; the Hawke era.

The neo-conservative or ‘neo-con’ in small measure creep into a few of the Teen Challenge Newsletter, with Peter Jones as Editor at MacGregor Terrace, Bardon (QLD 4065). It was of no real consequence as a lasting impact, but only to say that Teen Challenge Inc. did not completely escape the politics of fear. As argued in previous essays, it was the educated that kept the stability in the organisation, but there were times that the best leaders let fear get the best of them. So, it is still very important to understand.

Figure 1. The Teen Challenge Bus, circa 1981. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Teen Challenge Inc. was a broadly conservative organisation which had a radical edge. This is seen in the awards it won during the decade:

- 1980. Charles Ringma received a 4BC Golden Award for Excellence for community service through the work of Teen Challenge;

- 1982. Charles Ringma received a Certificate of Award from the Bardon Lions Club in recognition of outstanding community service;

- 1983. Charles Ringma received the 1982-1983 Lions District Governors Community Service Award for the work of Teen Challenge; and

- 1987. Alex Spencer received 1987 Queensland Award for Youth Achievement by the Queensland Day Committee

The broader Queensland society saw the organisation in a certain light – with a certain conventional attitude to the way things were done, and a safe organisation to honour. The perspective was true as it goes, but it also meant that few understood the nuances in the scope of beliefs within Teen Challenge Inc., where conventionality was not so respected. Nevertheless, the awards also related a sense of the new, and of progress.

Figure 2. Claude as the first Post-Ringma Directorship. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The New Post-Ringma Governance and Administration in the mid-to-late 1980s inevitably took a firmer conservative turn. Governance and Administration often is more conservative from the perspective of professionals on the ground, who are impatience for needed change. The changing of the guard in Teen Challenge Inc., with the absence of those, who cut their teeth in the organisation with radical gusto, the corporative concerns took centre stage, particularly as the passage through the 1990s and its neo-con spirit. The language of corporation was in transition or entanglement during these years, and several trends followed. It meant a slide into the thinking from broader thinking of conservative business models and ending up in the full neo-con speak on the corporation competing in markets, language of defence and even war.

The language is traditional, biblical, and defensively conservative, however, it ebbs and flows in the historical shifts, and the early, mid, and late 1980s you can see the global temper rising during the Iran–Iraq War (1980-1988), Contra War (1980-1983), Lebanon War (1982), Falklands War (1982), Invasion of Grenada (1983), First Intifada (1987), Bougainville Civil War (1988-1989), Invasion of Panama (1989-1990) First Liberian Civil War (1989-1997), and with bloody conflicts on the Arabian Peninsula and the Horn of Africa, and the successful or attempted coup d’état. It was not that more was killed in this decade, or that wars lasted longer or more intense, but it was the language of culture legitimation for war. It was ideological in the extreme, returning to the imperialistic rhetoric that a decade ago had thought no longer existed as the dominant partisan policy. The influence was there across the whole culture and resistance was difficult.

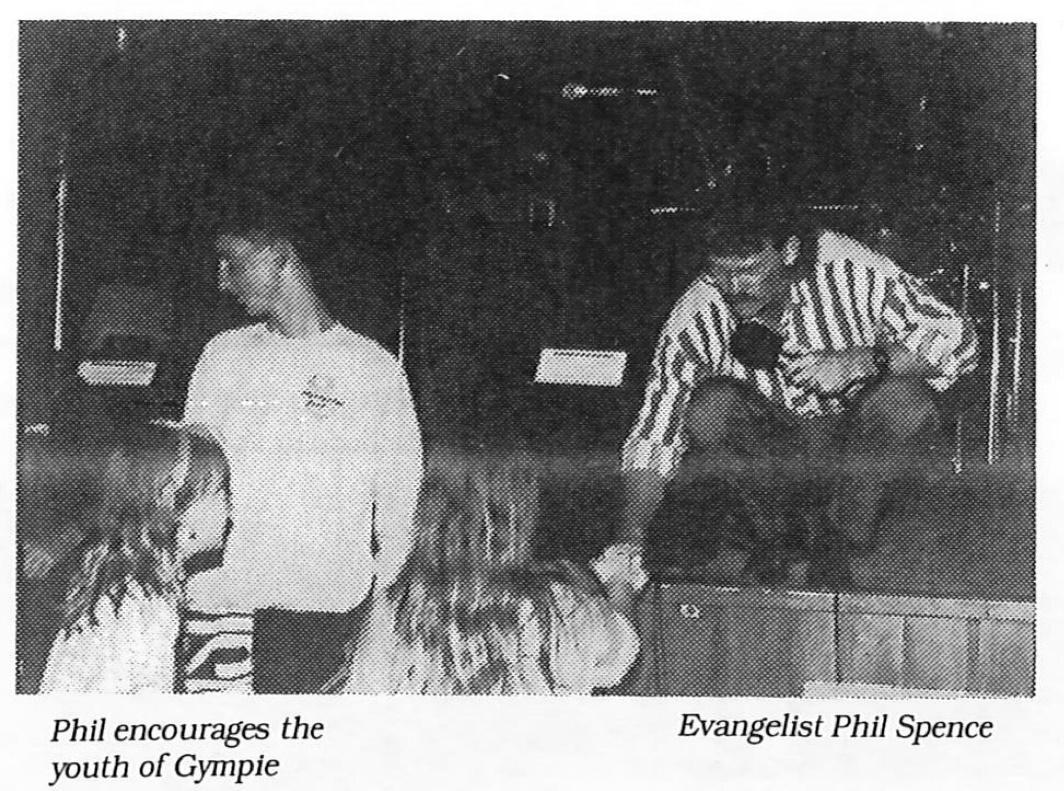

Figure 3. Alec Spencer, Manager, Hebron House, circa 1985. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Continued Outreach

In balance to the new language was the old language of saving souls. It provided, in the progressivist history of Teen Challenges, counterexamples to the influence of the American Revivalist Tradition (ART), as described in the author’s doctorate. Indeed, the author argued that Teen Challenge Inc. from the beginning was an archetypal example of the resistance to ART. What Teen Challenge Inc. did was theologically to turn the concept of revivalism on its head. Most of the rugged individualism was stripped away, and yet the revival was no longer the socializing devise of a nation. It was to revive a person in the Holy Spirt from a life of addict to a disciplined life. Gone was its imperialization from the United States, and the inability to critique the cultural bubble.

Outreach was now about healing the person, not a conformity to a worldview.

Community Education

The drug prevention programs of the 1970s in schools and churches were now becoming seen as community education. ‘Community education’ was the new buzzword but its semantics was substantive through communitarian scholars, such as Alasdair MacIntyre. In 1988 Claude Boulenaz was the speaker for the “Cooroy Community Drug Awareness Night” (15 July 1988). The tone of the lecture or talks differed to that of previous TC speakers. There was less concern to play up the dangers, and only highlighting a question of ‘drug awareness’, when there was a greater awareness than a decade before.

Youth Activity Centre

The Youth Activity Centre had remained the mainstay of outreach across the decades. However, by the end the politically-turmoil decade, this type of outreach was greatly declining. There are probably a few different factors, but one cannot ignore that the ministry had been struggling in the Fortitude Valley, the heart of the political and policing corruption. Even though, under Charles Ringma’s leadership, the organisation was among those who stood against a corrupt and immoral state governance, streetwise youth could not think well of a conservative Christian organisation in these circumstances.

Figure 4. Teen Challenge Gympie Sausage Sizzle and Gospel Concert, 1989. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Rallies, Concerts, and Reunions

For the 1980s, it is difficult to find large evangelical rallies where Teen Challenge Inc. was once so closely linked in. In 1989 the Assemblies of God pastor and Teen Challenge worker, Phil Spence, was the guest speaker at the Gympie’s Teen Challenge Sausage Sizzle and Gospel Concert, held in the Nelson Reserve in Monkland Street. It spoke of the continuing local mild revivalist affair.

Figure 5. Walter Santo at Hebron House, 1988. Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The global evangelical world had been rethinking the value of the mass culture American revivalism. The critical literature was increasing among scholars, including this author. The 10th Anniversary Celebration of Hebron House (1988) had enjoyed the ministry of the guest celebrity, Teen Challenge evangelist Walter Santos. The location for the event was King George Square, the major site for ‘street-witnessing’ in the 1970s and early 1980s. Among the aging Teen Challenge workers were those who were wising up to the hollowness of cold-faced evangelism, and that discipleship was better without it. There were too many stories of streetwise youth finding ‘King George Square’ pronouncements on the ‘four spiritual laws’ a complete turnoff. It reeked of fundamentalism. No doubt Church-run evangelical rallies, concerts, and reunions continued into the 1990s, recycling with new zealots, but Teen Challenge Inc. had matured as an organisation.

Concluding Remarks

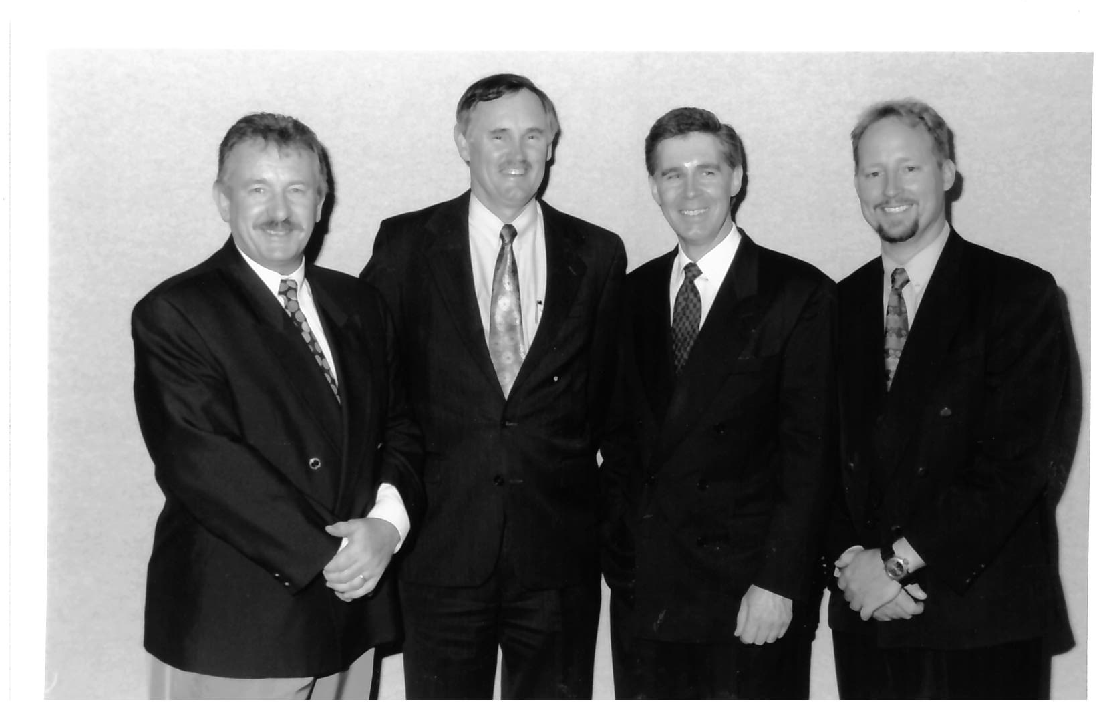

Figure 6. Teen Challenge Leaders of the 1980s, left to right: Pastor John Lewis (Northside Christian Church), Mike Tidbold (Chairman, Teen Challenge Inc.), Mike London (Patron), and Alec Spencer (Executive Director). Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The year 1989 marked in Queensland society the collapse of a corrupted Nationalist regime. Although the more militant conservative Christians defend the legacy in the long successive governments of Sir Johannes Bjelke-Petersen – by playing on the benevolence of the ‘regime’ (noun 1. a government, especially an authoritarian one) – forgotten is the spiritual damage done among a people.