Institutions and Schools…

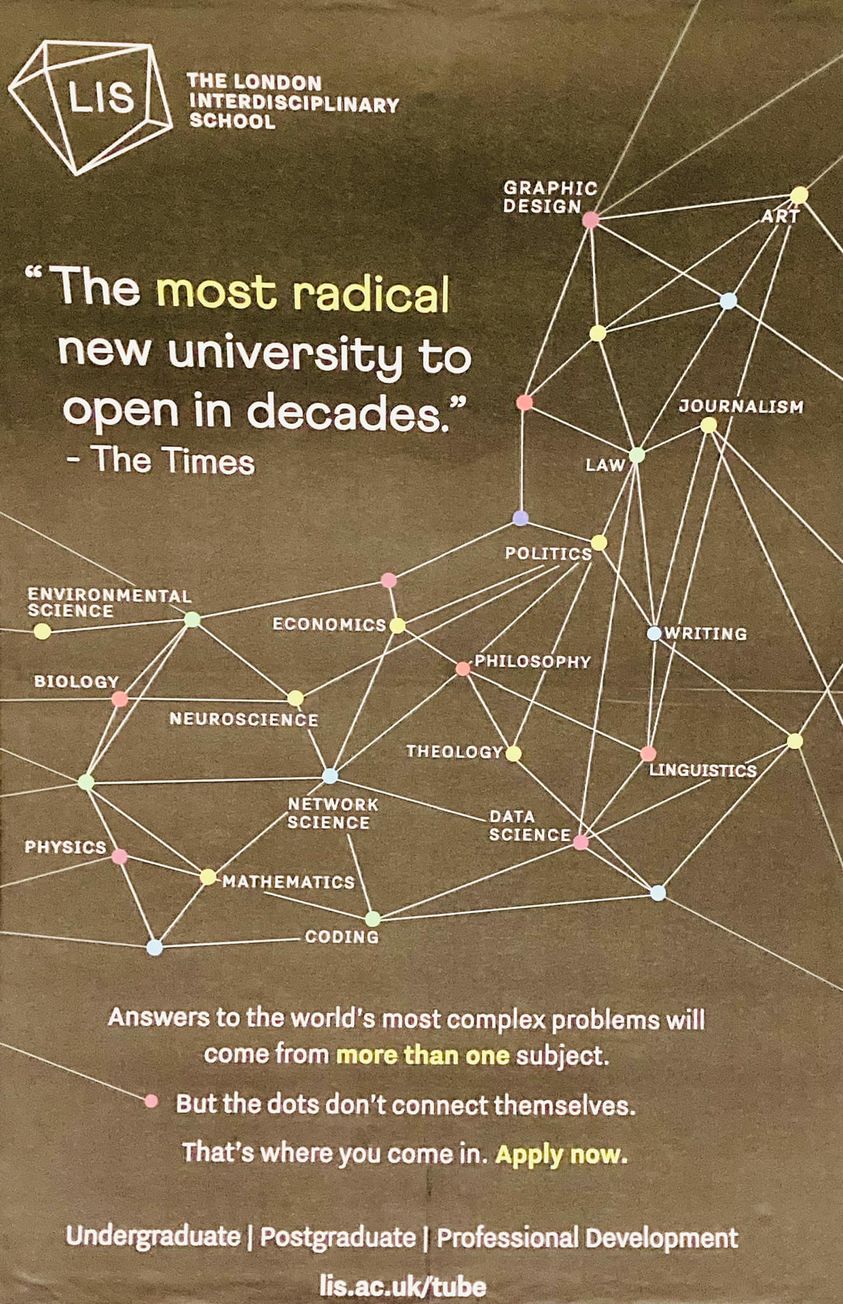

A friend passed on, through the online world, this image of an advertisement in the London tube, Baker St. on the northbound Bakerloo line (read critically the image).

This is not a paid advisement. It is yet-another call for university management to wake up to itself, and realise that in rejecting persons and models 30 years ago, and racing after the nouvelle or nouveau sub-cultural trend of the times, “only … [then] the dusk starts to fall does the owl of Minerva spread its wings and fly” (Hegel, Philosophy of Right).

“The most radical new university to open in decades.” Only since higher education policies were diverted, three decades ago, into neo-liberal and neo-conservative schemas, in a blanket (stupidity in the willful sense) judgement that rejected previous and worthy schemas from the 1950s to the mid-1970s. And so, the history spirals around. I have explained the historiography, but am I listened to as independent higher education researcher, with ten years’ experience employed in the University of Melbourne?

American sociologist Randall Collins’ The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change (1998) explained the sociology, 25 years ago. His The Credential Society (1979, republished 2019) is a classic on the role of higher education in American society and an essential text for understanding the reproduction of inequality. Note the original publication date, 1979.

“Radical” !!!!! It seems university managers’ ignorance (in the true sense of not knowing) or stupidity — take your pick – knows no boundaries. Of course, the excuse of today’s university managers is that they were not born when these decisions of managerialism were made. But the excuse is only good in the current decisions to reverse mistakes made in the past. Perhaps, the reader can send this blog piece to a university or even a college manager, to assist them by creating the historical awareness. I am all for learning from mistakes.

So, lets dig deeper into the history of Australian higher education policy, and there should be no doubt to the argument presented. In 1975 Griffith University, Queensland, was founded. The policy created in the Griffith model (and similar with other universities, such as Latrobe in Victoria) was to have faculties made up of interdisciplinary schools (and thus ‘schooling’). Again, note; this is 1975. This was an educational trend of the mid-1970s, and whatever problems, it was very worthy, and the London Interdisciplinary School should be praised for following the minority well-tread pathway (“radical”). The larger institutions (“competitors”) then have problems turning back the ship of state! Explaining the reason why in the neo-neo-liberal and neo-neo-conservative policies, from the 1980s, goes to the text of Stanley Aronowitz’s, and Henry A. Giroux’s Education Under Siege: The Conservative, Liberal and Radical Debate over Schooling (1985).

Here the point is that university managers have issues understanding the past-present problem because their cognition is far too institutionalised and ‘schooled’.

The interdisciplinary literature on institutionalisation and critical thinking goes back to the mid-to-late 1960s, and to the radicals of the time, such as Stokely Carmichael and Herbert Marcuse. With the revolutionary rhetoric cut out, the radical propositions are mainstreamed today. It is only the militant “New Right” (a term coined in the 1980s) who disagree because they wish to ferment their own revolution. The mainstream university managers will quietly admit the critique, but ignore the call to do something about the damage that neo-liberal and neo-conservative policies have done. What something? How about starting with discriminatory practices based on the older age of an applicant.

As these neo-liberal and neo-conservative schemas were institutionalised, persons who resisted the ‘trendy’ paradigm were removed from employment or had opportunities for work contracts curtailed.

That is the institutionalising problem. The schooling problem was unmasked by Iván Illich’s Deschooling Society (1971). Recently, in Rosa Bruno-Jofré’s Ivan Illich Fifty Years Later: Situating Deschooling Society in His Intellectual and Personal Journey (2022) there is clear demonstration of a willful political diversion away from Ivan Illich’s schooling critique in the institutions; working off tactics of ideological boxing and misconstruing Illich’s claims. Any yet there is nothing new here. In 1976 we had a Queensland senior lecturer, Michael Macklin, publish When Schools are Gone: A Projection of the Thought of Ivan Illich (note: St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press, 1976). Macklin made it undeniable to the hearing of the University of Queensland what the Illich model meant. That senior lecturer went onto to be the Dean of New England University, another institution with some familiarity with interdisciplinary schooling.

The Illich model was never about the destruction of any school, it was about de-institutionalisation of schools by removing the schooling structures which create institutionalised cognition. The claim of Illich wanting to destroy the (any) school was the rhetoric of the late-1970s-1980s militant “New Right”, and to their shame, university and college (the institutions) managers believed them.

The Illich model was informed by the movement of Catholic personalism and, as a so-called ‘radical’ model, today it is mainstreamed in minority pathways. The problems are that university and college managers, and the governors they inform, are either still stupid or ignorant (both in semantic sense outlined), when there are no honest conversations from the institutions in the public square (see the critiques of American sociologist, Robert Wuthnow).

The fact is the Australian higher education policies are not changing and the funding model which supports it is not changing. University managers make the mea culpa at in-house conferences, but to date they have not yet committed to make the uproar to initiate serious policy changes. The meaning of an uproar is to be ready on the verge to revolt. Institutions have revolted against other institutions (state-federal governments) in history.

Perhaps, it will take an uproar in the public square. The fact is that the Australian public is being severely under-educated on the global scale. Is there really equality of opportunity? This call is the same as the call for peace from the culture-history war, by knowing the history and acting in good faith.