Synopsis: A review of F. Scott Fitzgerald‘s The Great Gatsby (read copy, Penguin Books 1950, 2008 edition). The book was published in 1926, from notes of 1922 and as set in New York’s Long Island and Manhattan Island in 1922. The landscape of the narrative, is considered, in the first section of the review, with reflections of a 2023 tour around the geography of The Great Gatsby, a hundred years later. The second section is a discussion of personalism from the book, and the third section makes a few comments of the relationship of the book and the messages of American modernism in the 1920s, considered a century later.

CONCEPT OF LANDSCAPE

Re-reading novel The Great Gatsby and watching Baz Luhrmann’s film (2012 trailer), The Great Gatsby, I realised I had been in the novel’s fictional geography, albeit a century later, during my 2023 American research tour. The film re-creates the fairly accurate sense of the novel‘s historic landscape, but fails to capture well the novel‘s personalism and cultural modernism, as American modernism was just emerging as literature in 1922. Henry James’ theme of New York’s binary of old money and new money is there, but added is the modern thematic visionary of Sinclair Lewis‘ Main Street (1920). If you wander around American townships you inevitably find a Main Street, somewhat updated, but nevertheless in both the intellectual and parochial small-mindedness which Lewis described in the early twentieth century. The more things change, the more it does not; a paradox of any intellectual history. Perennial themes in new or recycled frameworks. I had spent an afternoon in Main Street, Northport, Long Island.

Image: Main Street, Northport, 10 Feb 2023

This is not the part of Long Island of Fitzgerald’s geographical recreation, using different names but with the same contours and pathways which existed. But the Centerport-Northport area, which is further east than Fitzgerald’s Manhasset Bay area, is a good place to start, as it is the location of Vanderbilt Museum and Planetarium, what remains of the ethos of the Jay Gatsby’s mansion, on an island famous for playboy mansions and parties.

These days the beaches of northern Long Island are more inviting to the American middle classes, and basically gone are the symbolic representation of the old-new moneyed Gilded Age. Summers are full of young families less concerned with the cultural prejudices of modernism. Sophisticated and moneyed hedonism is less to be seen on the summer vacation, but with the remaining private mansions some of the ethos lingers in the shadows.

Image: Neville at Centerport Beach, 10 Feb 2023

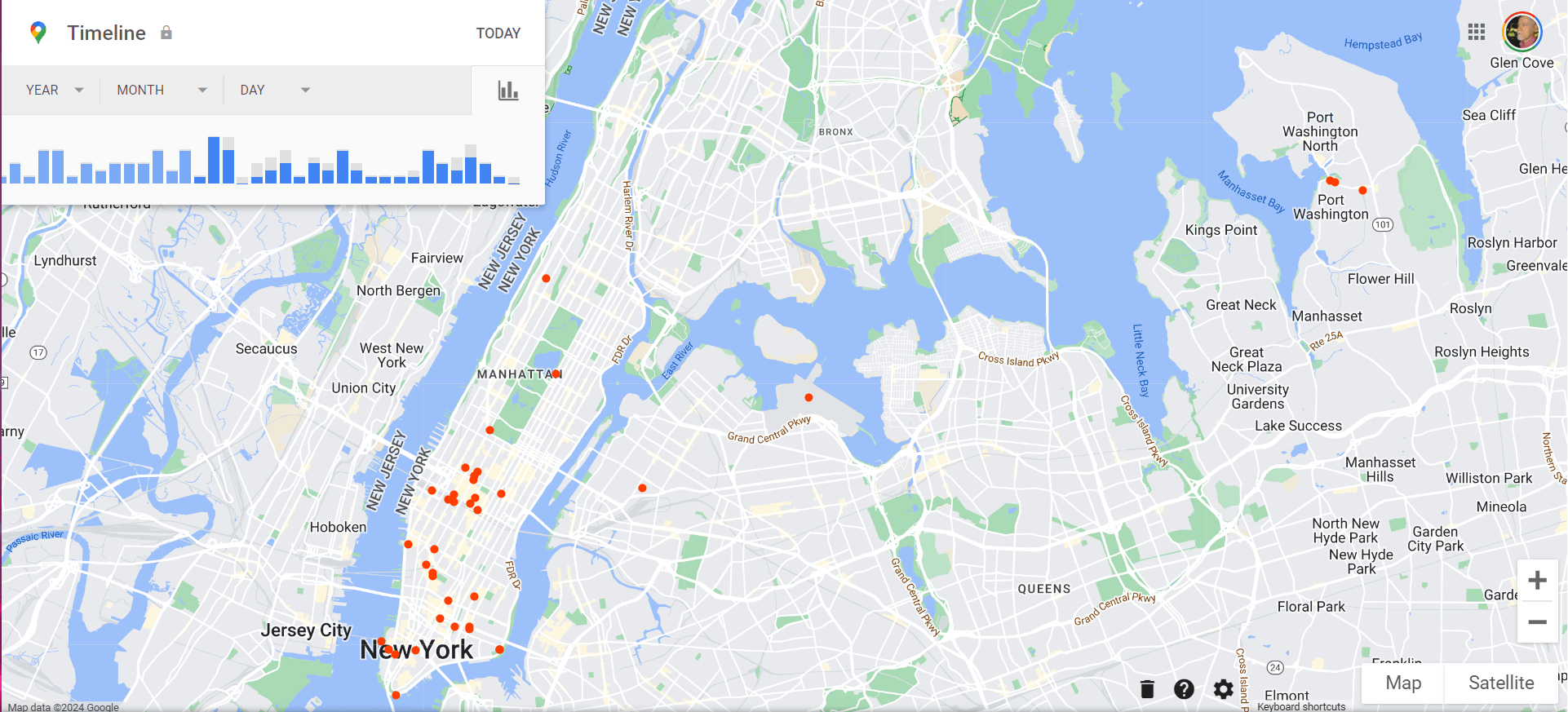

When not being driven in fast automobiles, Nick Carraway transverses between the ‘West and East Eggs’ area and Midtown and Lower Manhattan by the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR). It was a February sunny afternoon I headed out of Pennsylvania Station on a journey to Port Washington, joined by my travelling host, Herb Klitzner, in Queens. This meant traveling through the Fitzgeraldian geography. At the time I had not taken the significance of the journey. I was on my way to the Port Washington Library with Lewis more in mind. The Library had a good size collection of Lewis’ papers and first edition books, but also had a few Fitzgerald reference materials. Lewises and Fitzgeralds were known to each other, mixing in New York literary circles during these early years of the 1920s.

Image: Neville at the Port Washington Library between the Fitzgerald and Lewis collections, 11 Feb 2023

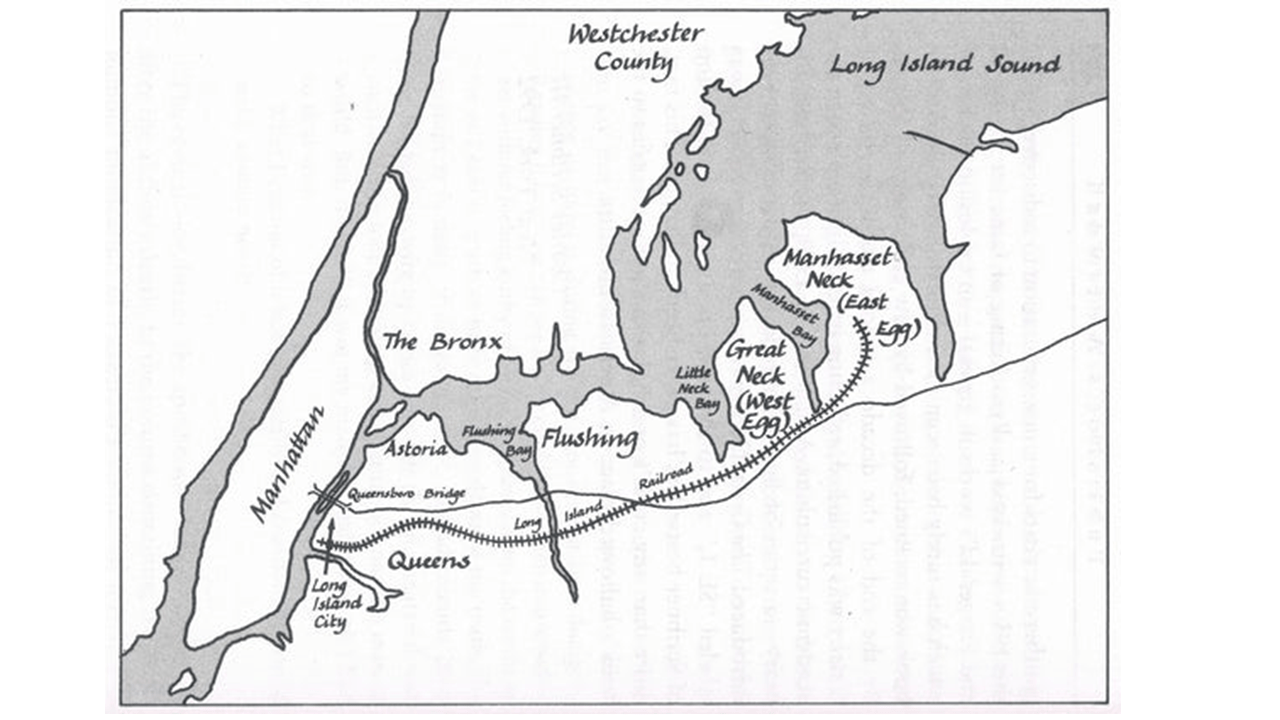

The trip to Port Washington is basically the same in 1922 but the appearance of the landscape has changed greatly. The webpage, Century Press, Letter No. 7 – Gatsby’s Geography, helpfully matches the novel’s fictional names to the actual Long Island sites.

Image: 1920s Sketch Map NY to LI. From Century Press, Letter No. 7 – Gatsby’s Geography, https://www.centurypress.ca/blogs/letters-from-century-press/letter-no-7-on-gatsbys-geography

Image: Neville’s Travel Map in the New York-Port Washington Area, Feb 2023

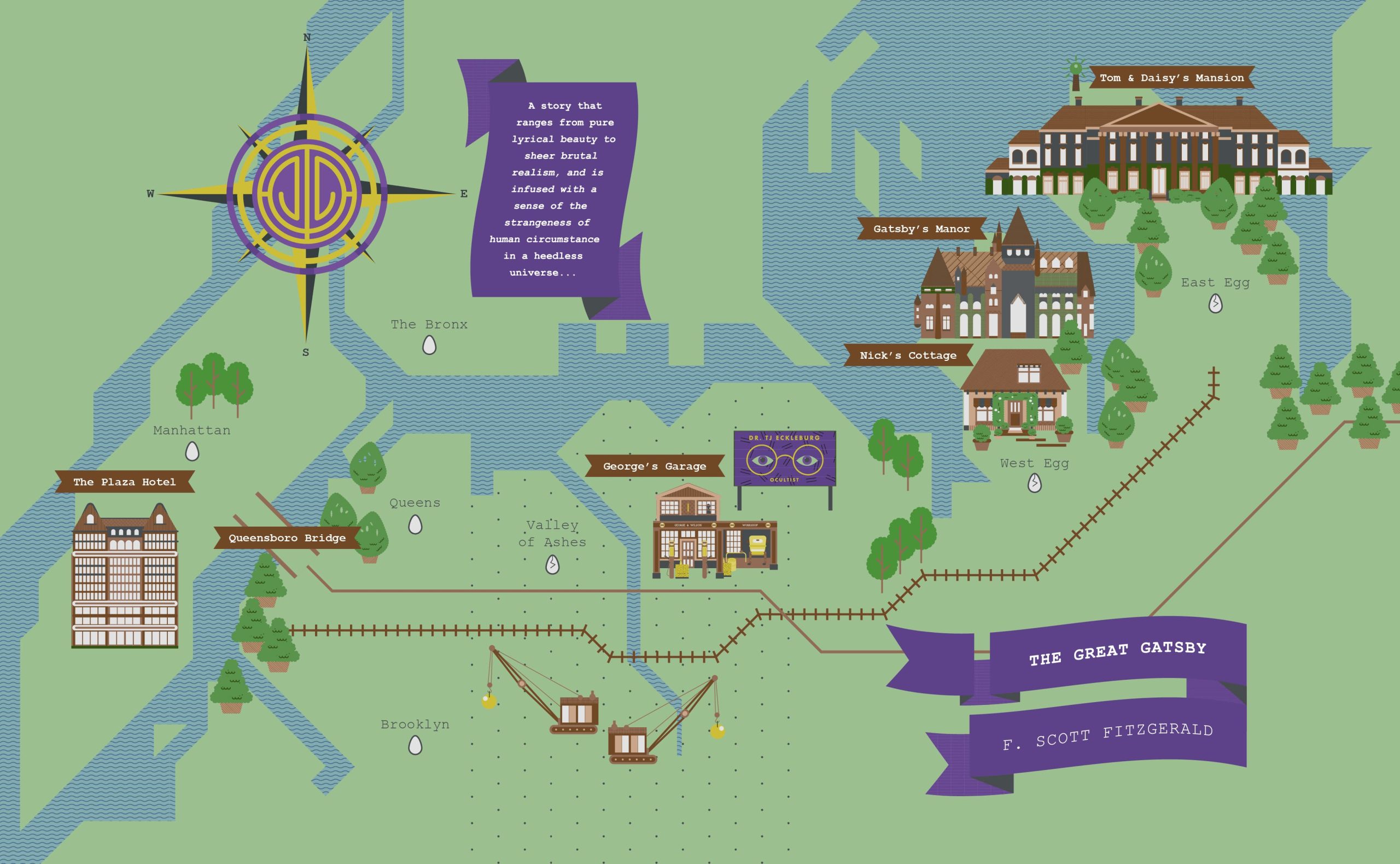

Flushing (true name) is part of Queens where George Wilson’s Garage is located, stared at by the eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg’s billboard. Jay Gatsby’s mansion is in the fictional West Egg (new money) and is actually Great Neck. East Egg is the area of the Buchanan’s mansion, and more precisely it is Plum Point, looking across the Bay to Gatsby’s Kings Point. Plum Point is just north of Port Washington. The fictional/actual Valley of Ashes is just across from the Queens railway stop (as in 1922), on the other side of Flushing creek which has been mostly built over, and exposed as Flushing Meadows Corona Park.

Source: http://treadwellburket.mtaspiring.edutronic.net/the-great-gatsby-analysis-settings/

The desolate scenes of the novel are gone, except in the evidence of swampland, feed from the Long Island Sound.

Image: View from the Long Island Railway journey, 11 Feb 2023

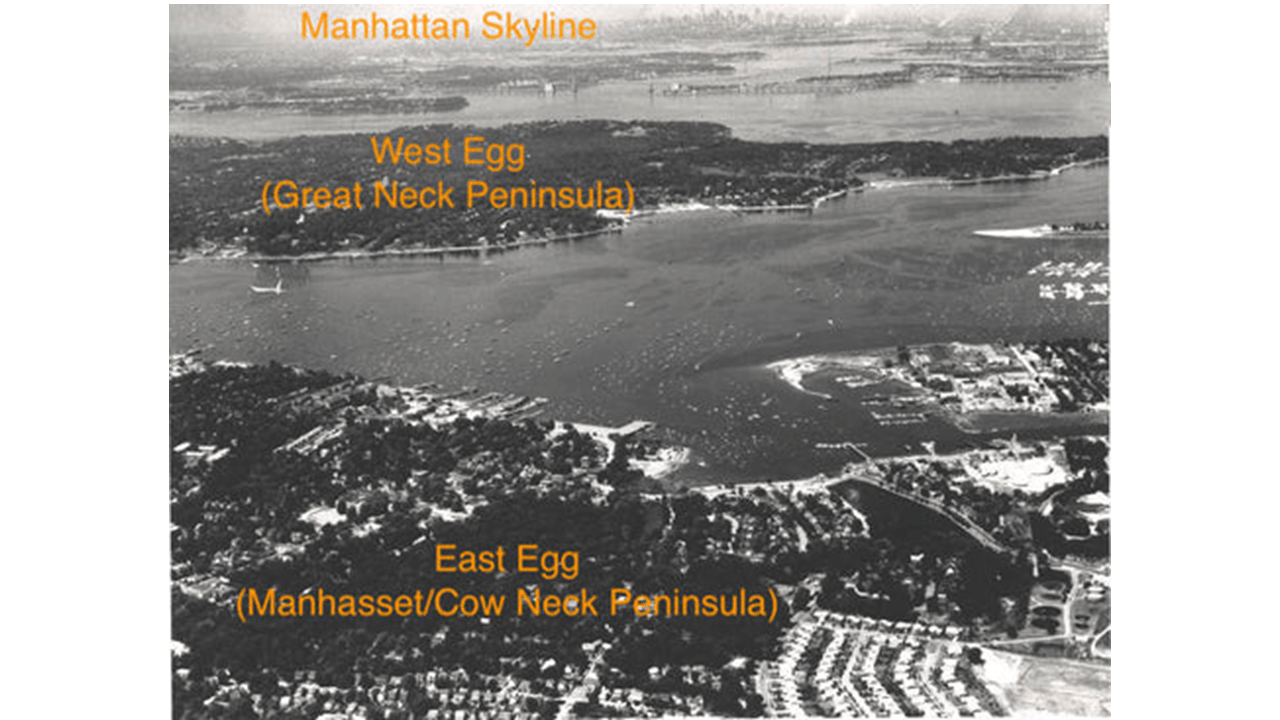

The landscape viewed in 2023 is not the imagined landscape of Fitzgerald in 1922. What we have to imagine are desolate hamlets, coastal villages, set through small inlets and lightly forested and narrow roadways. There are only a few old black and white photographs which capture the 1920s landscape of the Long Island playground.

Image: 1920s Aerial Image of Gatsby Area. From Century Press, Letter No. 7 – Gatsby’s Geography, https://www.centurypress.ca/blogs/letters-from-century-press/letter-no-7-on-gatsbys-geography

The landscape of the early 1920s Long Island speaks to us of American modernism. Visions of relaxing suburban life outside of the madness of the Megacity, and yet the truth was that it came with the Valley of Ashes. It is the industrial dumping site, a significant representation of industrialisation in the landscape, which in the twentieth century came and went, and the prosperity of the Jazz Age had long gone with the loss of this economy.

CONCEPT OF PERSONS

There are two main frameworks in thinking about the concept of persons. Personalism, a diverse set of philosophical doctrines on what a person is, and Philosophical Psychology, as oppose to therapy, and is the explanatory basis for psychology.

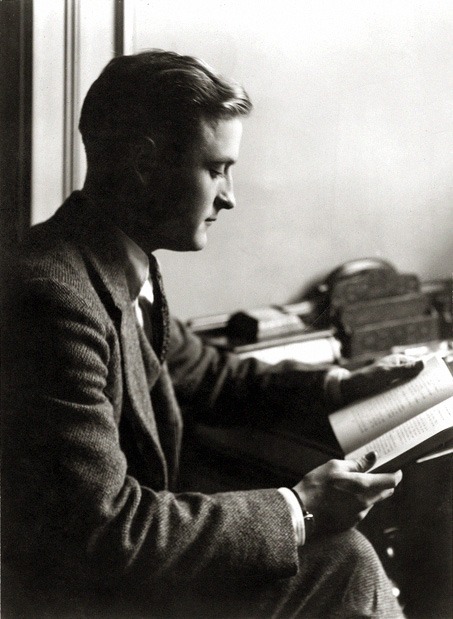

Wikipedia Image: A black-and-white photographic portrait of Jazz Age writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society. This photo appeared on the rear of the original dust jacket of Fitzgerald’s second novel, The Beautiful and Damned, which was published in March 1922 by Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Which any frameworks are being considered, there are common terms to illuminate the thinking of the text: personality, and gendered relations (including sexuality). The philosophic reflection on the text can go much further to types of judgement, caring and carelessness or ruthlessness, and thinking on ourselves and the significant other.

In personality:

“If personality is an unbroken series of successful gestures, then there was something gorgeous about him”

“He smiled understandingly-much more than understandingly. It was one of those rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it, that you may come across four or five times in life. It faced–or seemed to face–the whole eternal world for an instant, and then concentrated on you with an irresistible prejudice in your favor. It understood you just as far as you wanted to be understood, believed in you as you would like to believe in yourself, and assured you that it had precisely the impression of you that, at your best, you hoped to convey.”

Nick Carraway is not Fitzgerald as the narrator, but it is clear that Fitzgerald, across the novel, is speaking to personalities he came across in his life, before writing the book. It is also clear, from the above quotations, that Fitzgerald introduces persons as the modernist perceives beauty and aesthetics. How many times in the “public relations” rhetoric are we told to smile.

Nick Carraway – a Yale University alumnus from the Midwest, a World War I veteran, and a newly arrived resident of West Egg, age 29 (later 30) who serves as the first-person narrator. He is Gatsby’s neighbor and a bond salesman. Carraway is easy-going and optimistic, although this latter quality fades as the novel progresses. He ultimately returns to the Midwest after despairing of the decadence and indifference of the eastern United States.

Jay Gatsby (originally James ‘Jimmy’ Gatz) – a young, mysterious millionaire with shady business connections (later revealed to be a bootlegger), originally from North Dakota. During World War I, when he was a young military officer stationed at the United States Army’s Camp Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky, Gatsby encountered the love of his life, the debutante Daisy Buchanan. Later, after the war, he studied briefly at Trinity College, Oxford, in England. According to Fitzgerald’s wife Zelda, he partly based Gatsby on their enigmatic Long Island neighbor, Max Gerlach. A military veteran, Gerlach became a self-made millionaire due to his bootlegging endeavors and was fond of using the phrase ‘old sport’ in his letters to Fitzgerald.

Daisy Buchanan – a shallow, self-absorbed, and young debutante and socialite from Louisville, Kentucky, identified as a flapper. She is Nick’s second cousin, once removed, and the wife of Tom Buchanan. Before marrying Tom, Daisy had a romantic relationship with Gatsby. Her choice between Gatsby and Tom is one of the novel’s central conflicts. Fitzgerald’s romance and life-long obsession with Ginevra King inspired the character of Daisy.

Thomas ‘Tom’ Buchanan – Daisy’s husband, a millionaire who lives in East Egg. Tom is an imposing man of muscular build with a gruff voice and contemptuous demeanor. He was a football star at Yale and is a white supremacist. Among other literary models, Buchanan has certain parallels with William “Bill” Mitchell, the Chicago businessman who married Ginevra King. Buchanan and Mitchell were both Chicagoans with an interest in polo. Also, like Ginevra’s father Charles King whom Fitzgerald resented, Buchanan is an imperious Yale man and polo player from Lake Forest, Illinois.

Jordan Baker – an amateur golfer with a sarcastic streak and an aloof attitude, and Daisy’s long-time friend. She is Nick Carraway’s girlfriend for most of the novel, though they grow apart towards the end. She has a shady reputation because of rumors that she had cheated in a tournament, which harmed her reputation both socially and as a golfer. Fitzgerald based Jordan on Ginevra’s friend Edith Cummings, a premier amateur golfer known in the press as ‘The Fairway Flapper’. Unlike Jordan Baker, Cummings was never suspected of cheating. The character’s name is a play on two popular automobile brands, the Jordan Motor Car Company and the Baker Motor Vehicle, both of Cleveland, Ohio, alluding to Jordan’s ‘fast’ reputation and the new freedom presented to American women, especially flappers, in the 1920s.

George B. Wilson – a mechanic and owner of a garage. He is disliked by both his wife, Myrtle Wilson, and Tom Buchanan, who describes him as “so dumb he doesn’t know he’s alive”. At the end of the novel, George kills Gatsby, wrongly believing he had been driving the car that killed Myrtle, and then kills himself.

Myrtle Wilson – George’s wife and Tom Buchanan’s mistress. Myrtle, who possesses a fierce vitality, is desperate to find refuge from her disappointing marriage. She is accidentally killed by Gatsby’s car, as she mistakenly thinks Tom is still driving it and runs after it.

Source: Wikipedia.

The modernist sensibilities are clear, in defiance to Nick’s father’s advice on judgement. Tom is a prig, while Jay is “worth the whole damn bunch put together”. These modernist sensibilities, however, do not escape, criticism of the modernist outlook. Daisy is shallow and George is a brute.

In Gendered Relations:

“He looked at her the way all women want to be looked at by a man.”

“Angry, and half in love with her, and tremendously sorry, I turned away.”

Jay’s quality of personality is mysterious. He has that secret knowledge of knowing the “way all women want to be looked at by a man.” Most men would also like to know. It is not only Jay’s imagined relations with Daisy, the singular and large dream he has build up, symbolised by the West Egg mansion. Nick’s relations with Jordan is also complex and full of illusions. The affairs of the heart are entangled with conflicting emotions and thoughts.

In Philosophic Reflection:

“In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since.

“Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,” he told me, “just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.”

“There are only the pursued, the pursuing, the busy and the tired.”

“I was within and without, simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life.”

“They’re a rotten crowd’, I shouted across the lawn. ‘You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together.”

There is irony in Nick’s final judgement of Jay. Jay’s character had no scruples other than his romantic vision of Daisy as the “nice girl”. He was in the end revealed as the bootlegger in the crime network of ‘Wolfsheim’ who is based on New York gangster, Arnold Rothstein. One of the biggest shortfalls in American modernism of the 1920s, and 1930s, was the celebration of brutal crime and thuggish characters, as if there were no significant moral or ethical judgements; only aesthetical ones. Unfortunately, there is a swing back to this kind of nasty love of criminality in our own time. Swings and round-a-abouts. For example the Ned Kelly mythology is celebrated, and then it is correctly criticised.

Wikipedia Image: Arnold Rothstein, New York Daily News – https://www.newspapers.com/image/391466253/ Daily News 29 Oct 1920, Fri · Page 40

In the more philosophic reflection, this is caring and carelessness or ruthlessness:

“I couldn’t forgive him or like him, but I saw that what he had done was, to him, entirely justified. It was all very careless and confused. They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

Carelessness description is a judgement appropriate for Tom and Daisy for most of the novel, but, at the end, when Daisy is vulnerable and Tom take something of redemption, Nick observes a tenderness between Tom and Daisy; after all, Daisy could not declare that there was never a time she loved Tom. It is only that the care within the coupling is exclusive and is careless to others. Daisy is shallow in her judgement, and Tom is an outright white supremacist. Their affective politeness is a matter of class behaviour, not genuine personal caring. When it comes to Wolfsheim or Arnold Rothstein, the situation is outright ruthlessness but masked within civil sensibilities. Against the romantic illusion, such criminals destroyed lives. The character of Jay Gatsby begins as an enigma, but, as his hidden life history is revealed, he is not so much careless or ruthless, but confused of mind. After his death, James’ father, Gatz senior, reveals a son who redeemed himself to the original family, making something of amends for his reckless ambition. His father had been given a house two years before Gatsby’s untimely end. Another aspect of the carelessness is the misjudgment that Nick’s father warned about. Tom had clearly set up George to murder Gatsby under the misjudgment of both Tom and George that it was Jay at the wheel of the vehicle that killed Myrtle. If Tom and George knew that it was Daisy, the judgement would have led in another direction.

In even more philosophic reflections, in how we each think of ourselves and the significance other:

“There must have been moments even that afternoon when Daisy tumbled short of his dreams — not through her own fault, but because of the colossal vitality of his illusion. It had gone beyond her, beyond everything. He had thrown himself into it with a creative passion, adding to it all the time, decking it out with every bright feather that drifted his way. No amount of fire or freshness can challenge what a man will store up in his ghostly heart.”

In the end, it is the capacity to revaluate our judgements that matters. As a good stoic, Nick’s father’s approach was to suspend judgement, but that is, realistically, a temporary position. It is only the romantic who fears disillusion who refuses the need for revaluation in judgement, which means that judgement has already been secured.

CONCEPT OF TIME-PAST

The Great Gatsby is a work that draws out the concept of time-past for us, a hundred years later. It would have been difficult for the readers in 1926 to appreciate the historiography which was only just happening in the emergence of American modernism as literature.

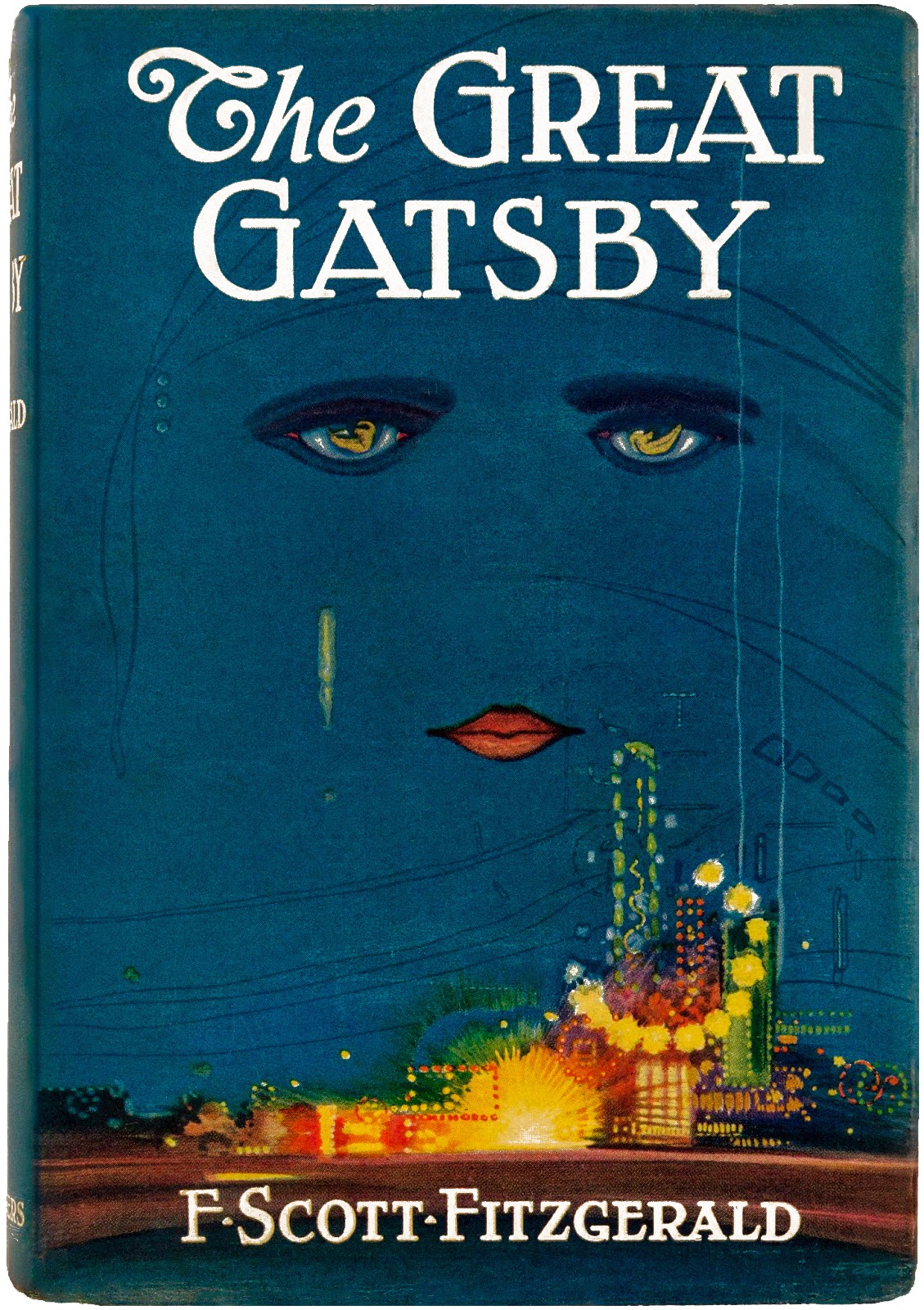

Wikipedia Image: The front dust jacket art with title against a dark sky. Beneath the title are lips and two eyes, looming over a city. Digitally restored and enhanced image of the first edition cover for F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby (1925). Original cover illustration by Francis Cugat (1893–1981) and published by Charles Scribner’s Sons.

The historiography of American modernism draws out several important themes: the nature of the past between what we think is modern and what came before; and the romantic recurrent past where modernism is confusingly represented as realism, but, in truth, European Enlightenment (as 20th century modernism) never escaped its Romanic roots. Fitzgerald originally, as American modernism, proposed the question of time-past: can we re-grasp what has come before?

On the nature of the past:

“Can’t repeat the past?…Why of course you can!”

This is the cry of the romantic Jay, and his great dream of Daisy became his mental prison. There are matters which cannot be changed. Time past is the most significant. History, the story of the past, spirals rather than repeats; which is to say there is a pattern of never returning to the exact same point, but a similar point of the past, just some way forward. Things have to change.

On Life and Death in the Time-Past:

“Let us learn to show our friendship for a man when he is alive and not after he is dead.”

“Life starts all over again when it gets crisp in the fall.”

“So we drove on toward death through the cooling twilight.”

If there are any perennial finality, it is life and death. One lifetime. One death (most usually). Yet, as the romantic would have it, there are cyclic seasons. We can be born again, in a sense. Things do go around in a spiral, but finally, “So we drove on toward death through the cooling twilight.”

On the romantic recurrent past:

“And so with the sunshine and the great bursts of leaves growing on the trees, just as things grow in fast movies, I had that familiar conviction that life was beginning over again with the summer.”

“His heart beat faster and faster as Daisy’s white face came up to his own. He knew that when he kissed this girl, and forever wed his unutterable visions to her perishable breath, his mind would never romp again like the mind of God. So he waited, listening for a moment longer to the tuning fork that had been struck upon a star. Then he kissed her. At his lips’ touch she blossomed like a flower and the incarnation was complete.”

Fitzgerald is influenced by the Nietzschean ideal of history as recurrence. But then, again, the words, “his mind would never romp again like the mind of God”, is striking. The phrase “mind of God” is romantic and mysterious. There is a strong sense that the reference is beyond the human mind. The sensible hermeneutics would guide us to merely the idea that, in the end, in death, there is stationary nothing. In the romantic mind, in life, there is a rapturous moment when time does stand still. The search for meaning has ended, not in the thought, but in simply being (or non-being).

On the conclusion of American modernism:

“And as I sat there brooding on the old, unknown world, I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn, and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.”

“Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—to-morrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther. . . . And one fine morning——

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

Wikipedia Image: The Great Gatsby, a film directed by Baz Luhrmann, 2013 Poster. Image linked to Film Trailer.

While we are still alive we dream in a green light, something romantic. It can become a prison for the mind, if we are unaware in judgement, but Realism does not end the Ideal. How can we say what is real unless we prepared to reevaluate our hidden idealism.

*****

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- J. D. Vance’s Insult to America is to Propagandize American Modernism - July 26, 2024

- Why both the two majority Australian political parties get it wrong, and why Australia is following the United States into ‘Higher Education’ idiocy - July 23, 2024

- Populist Nationalism Will Not Deliver; We have been Here Before, many times… - July 20, 2024