Let me be straight up, so as not to be confused on my clear and intelligent point. I do not expect fiction to be any closer to accuracy than what it is, fiction. It is rather an issue of the antiquarian, and what that truly means. Antiquarianism, according to the Wikipedia article should be seen as follows:

The essence of antiquarianism is a focus on the empirical evidence of the past, and is perhaps best encapsulated in the motto adopted by the 18th-century antiquary Sir Richard Colt Hoare, “We speak from facts, not theory.”

Immediately we have the critical problem of antiquarianism. There are no facts without theory. Ask Charles Sanders Peirce who was an American intellectual in the Late Victorian era. The issue I am addressing is not that films and novels are not accurate, but they have become incredibly loose with facts, and, indeed, the truth. It is a confusion in modern fiction between surrealism and the type of modern fiction that does better to deliver a factual and truthful point (see Virginia Woolfe’s remarks in the modern fiction link) . Take Christos Tsiolkas’ film review of Yorgos Lanthimos’s Poor Things.

In this film, Lanthimos has ceded ground to McNamara, whose ambiguous fascination and repulsion with royalty and power shows a decidedly English influence. The screenwriter’s vision worked magnificently for The Favourite, which both celebrated and derided aristocratic privilege, but it was less successful in McNamara’s television series The Great, where his portrayal of the Russian monarch Catherine the Great was limited by his Anglocentric lens. The Empress’s court was ridiculous but never terrifying. The Great’s surrealism was comic but without danger, and reminded me of the films of Terry Gilliam. I adore Gilliam’s work with Monty Python, but his films take the accoutrements of surrealism and graft them onto childlike phantasm. In the process, he strips them of any threat. Brazil denuded George Orwell’s 1984 of terror and 12 Monkeys was an undisciplined reimagining of Chris Marker’s uncanny short film La Jetée. Even with dangerous material, Gilliam’s impulse was to tame it, to switch on the light. I don’t think it’s an accident that his aesthetic is the dominant cinematic influence on Poor Things.

Poor Things is entertaining as surrealism but it is not entertaining as modern fiction. Surrealism is deliberately and truly antiquarianism, as everything out of place and time; to make a philosophical point, not a historiographical one.

In his essay “On the Uses and Abuses of History for Life” from his Untimely Meditations, philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche examines three forms of history. One of these is “antiquarian history”, an objectivising historicism which forges little or no creative connection between past and present. Nietzsche’s philosophy of history had a significant impact on critical history in the 20th century.

I have explained this in one of my previous blog articles.

And yet the local obsession for modern fiction, outside of Virginia Woolf’s warning, keeps shitting on history. It is not merely the antiquarianism but that such local attitudes hides any understanding of the intellectual history. If Poor Things is taken as modern fiction, and not pure surrealism, there is the loss of truly understanding Gothic Revival architecture, infrastructure, and the period innovation. Indeed, such an entry is hopeless in understanding Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus, as an 1818 novel, which makes it Georgian era, not Late Victorian.

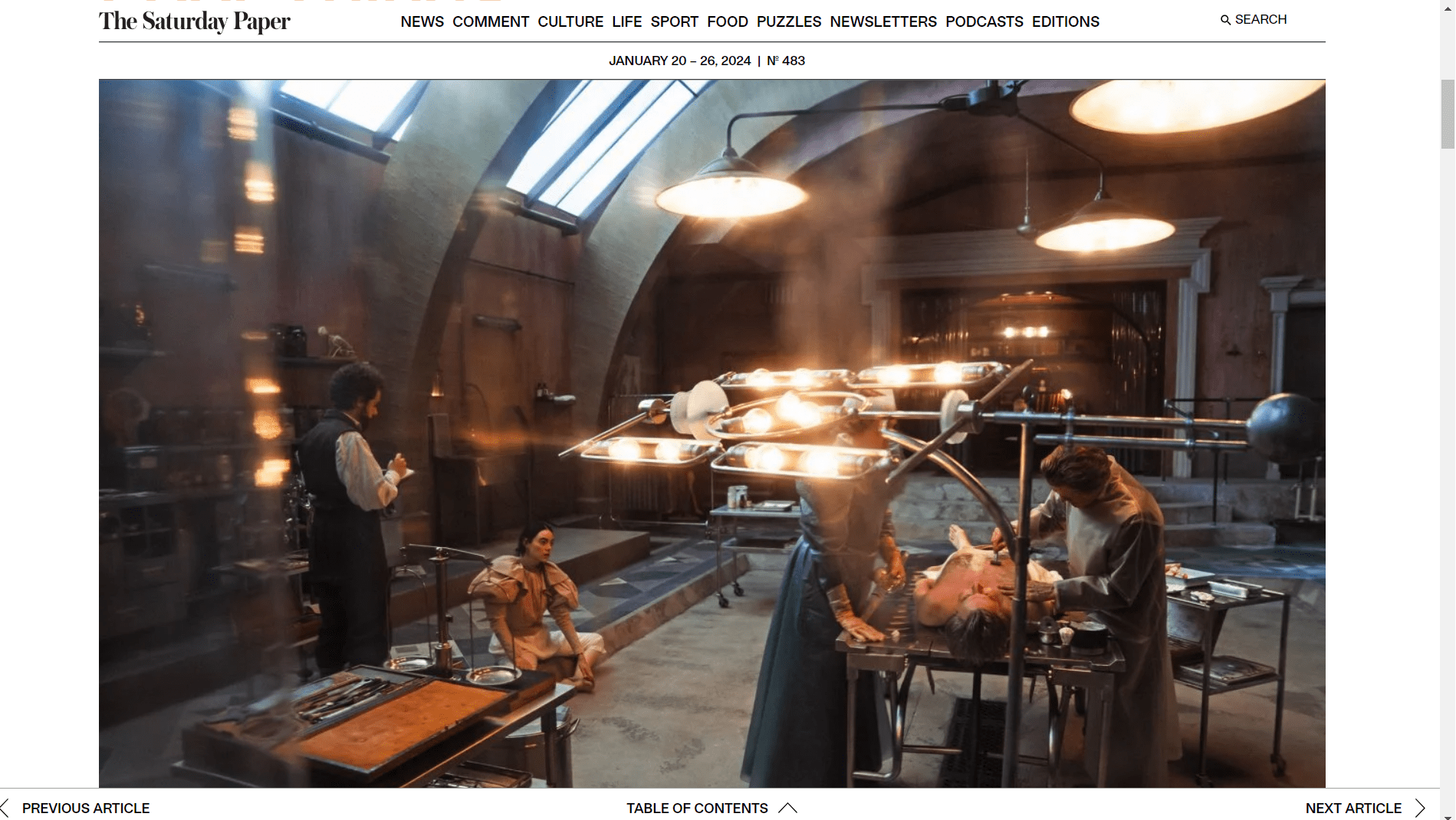

Featured Image: A still from the film Poor Things in Christos Tsiolkas’ film review, ” Frankenstein revision falls flat as Emma Stone and Mark Ruffalo fail to save Poor Things” In The Saturday Paper, January 20 – 26, 2024 | No. 483. How many items of antiquarianism can you find in the image? The scene is set as Late Victorian.

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- Dear grossly, ethically, corrupted - December 21, 2024

- Thoughts with a Professional History colleague on “Artificial Intelligence” - December 21, 2024

- Stephanie M. Lee on “AI by omission”, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Thursday, December 19, 2024 - December 20, 2024