by Neville Buch | Oct 26, 2022 | Article, Blog, Concepts in Educationalist Thought Series, Concepts in Public History for Marketplace Dialogue, Concepts in Religious Thought Series, Intellectual History

Introduction

Today, we hear stories of Orthodox Judaism, and in this recent article from The Chronicle of Higher Education, we learn that ‘new orthodoxy’ is a ‘thing’.

Image: Online story, Sylvia Goodman. ‘Alternative’ or ‘Sham’? Yeshiva U. Created a New LGBTQ Club — but Won’t Recognize the One That Sued, The Chronicle of Higher Education, October 24, 2022.

Dogmatists have been great at denying ‘new orthodoxy’ as a ‘thing’ since the claim brings modification to ‘correct belief’, creating incorrect belief; according to the dogmatists. However, the existence of many ‘new orthodoxies’ proposes an inescapable problem, for the dogmatist. The problem here is not confided to Orthodox Judaism, or even western religions, but any belief system which attempts to avoid admitting systemic error.

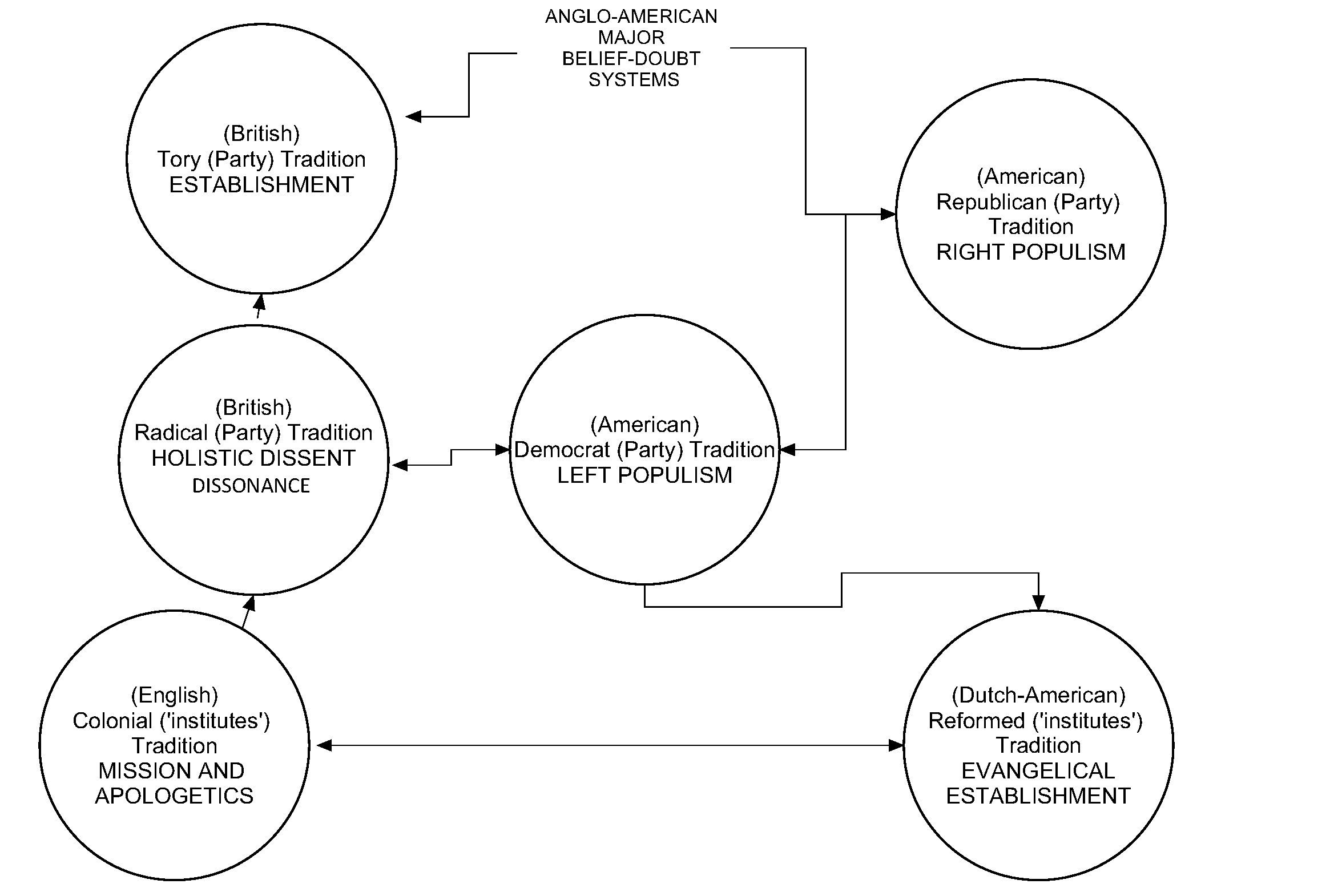

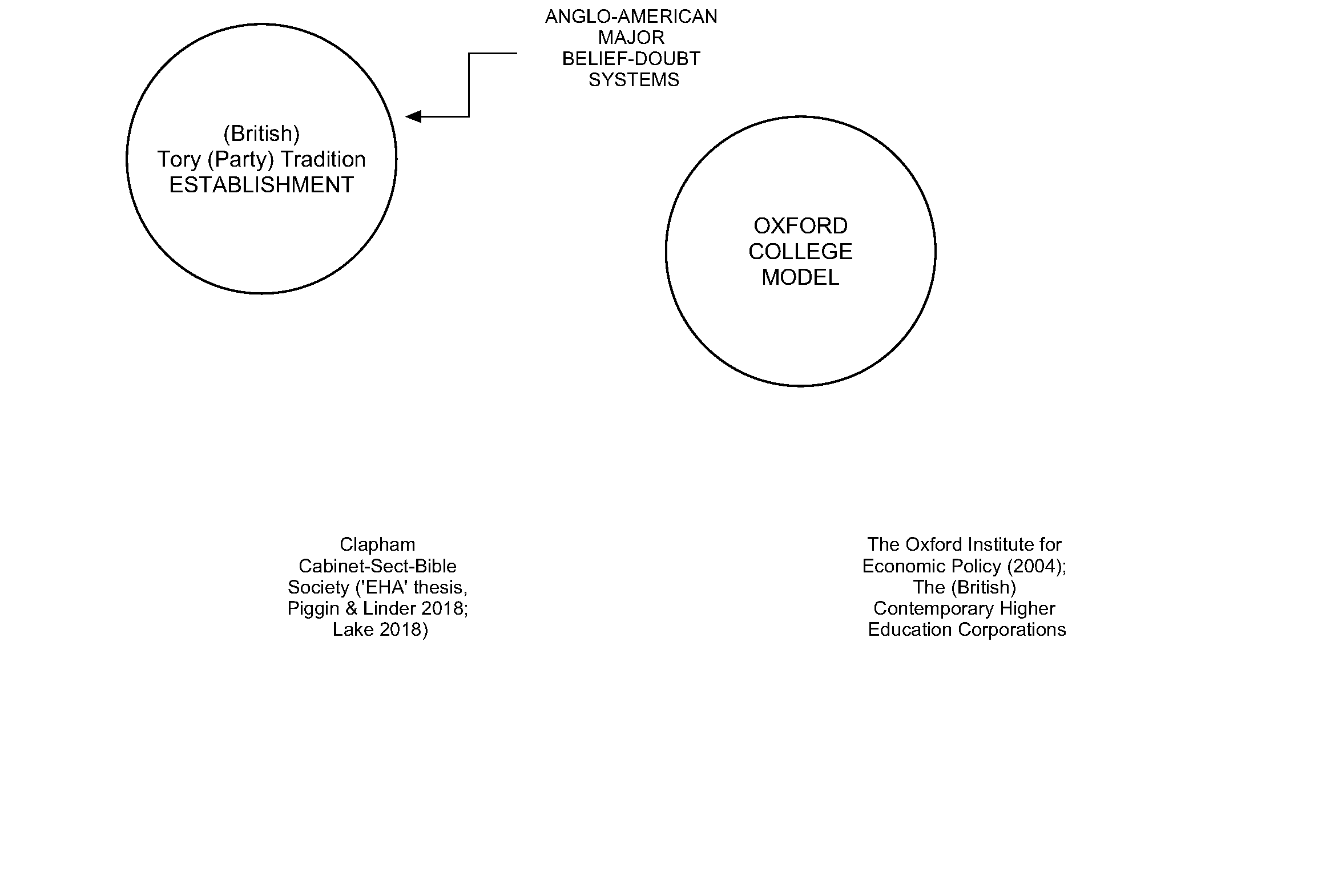

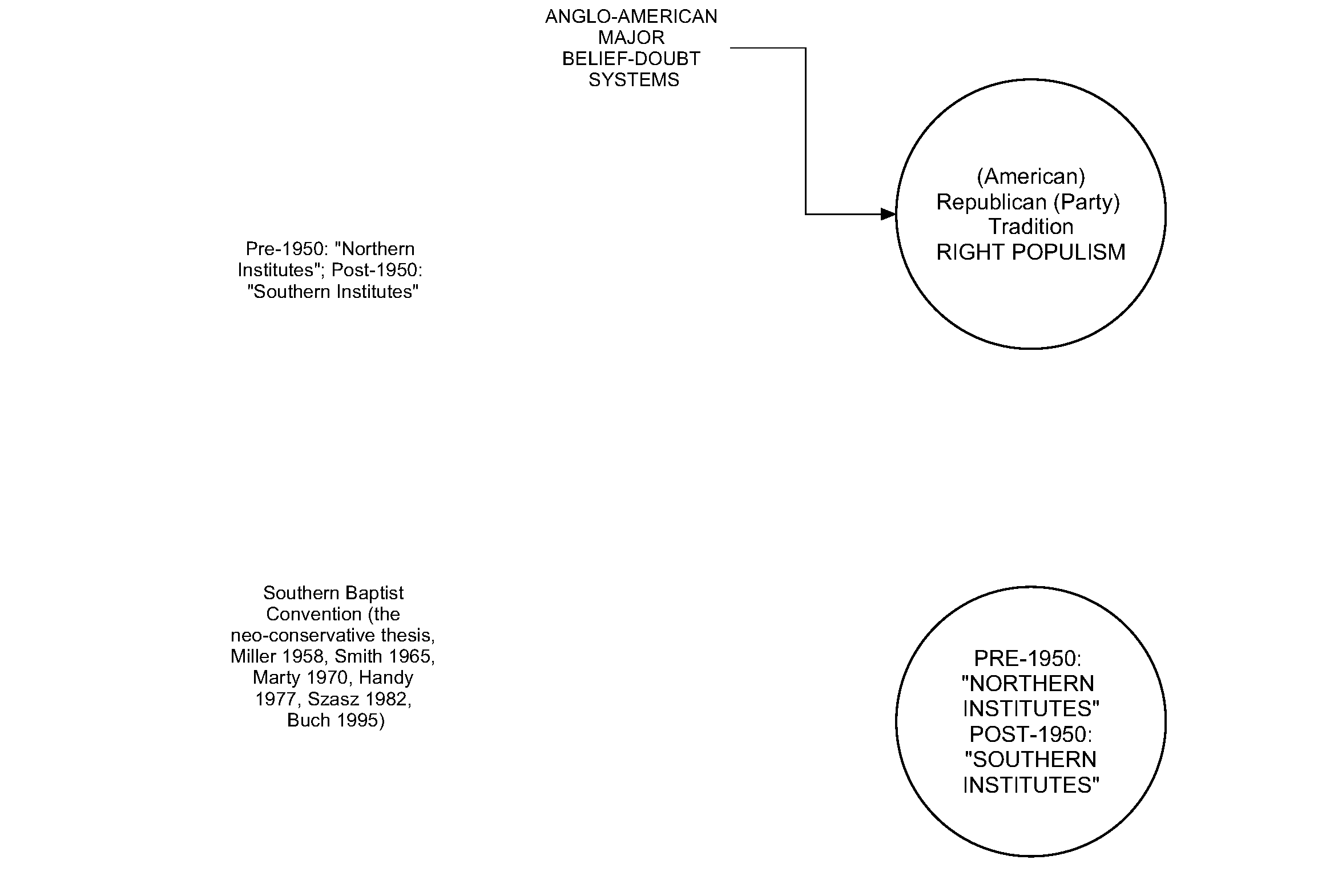

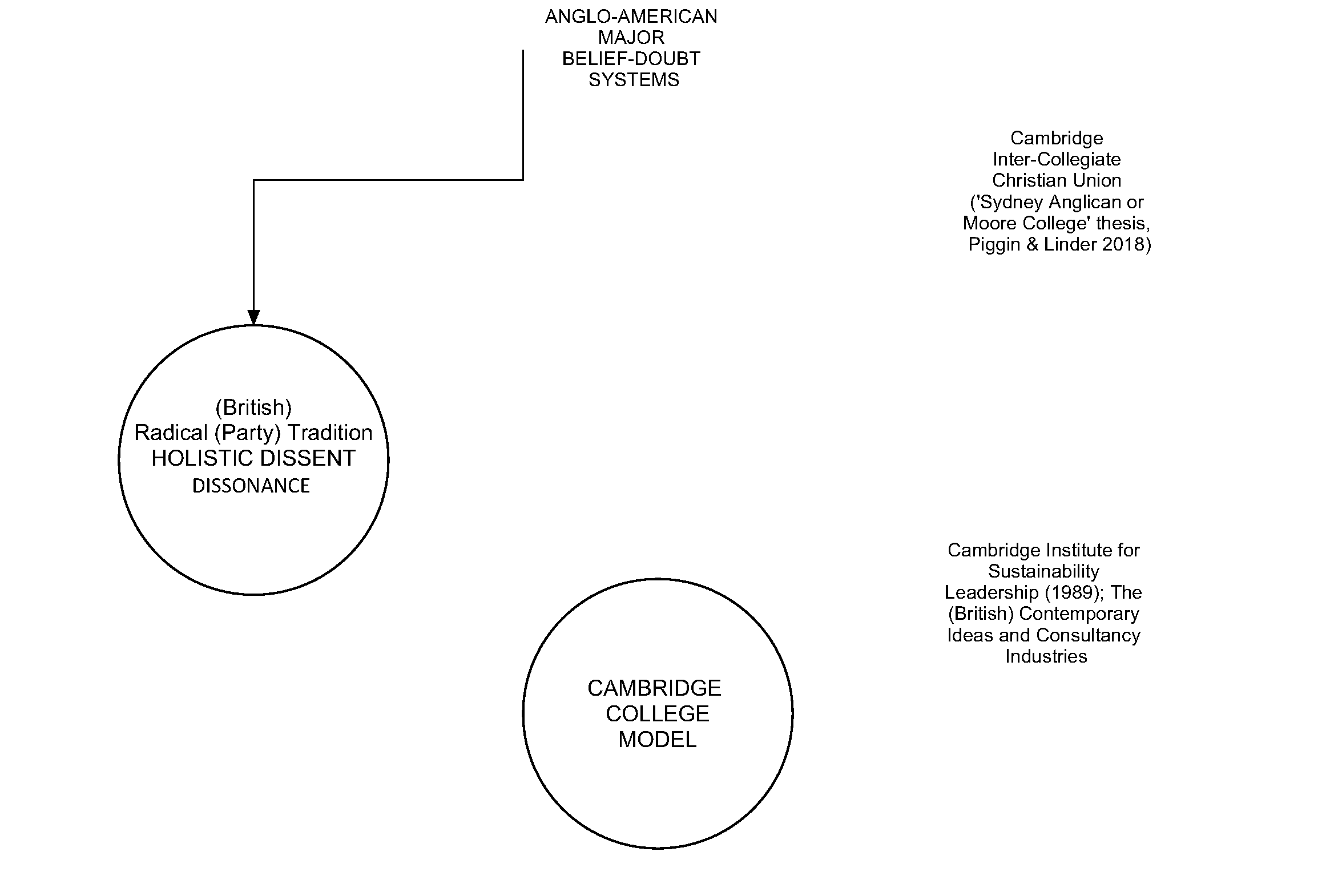

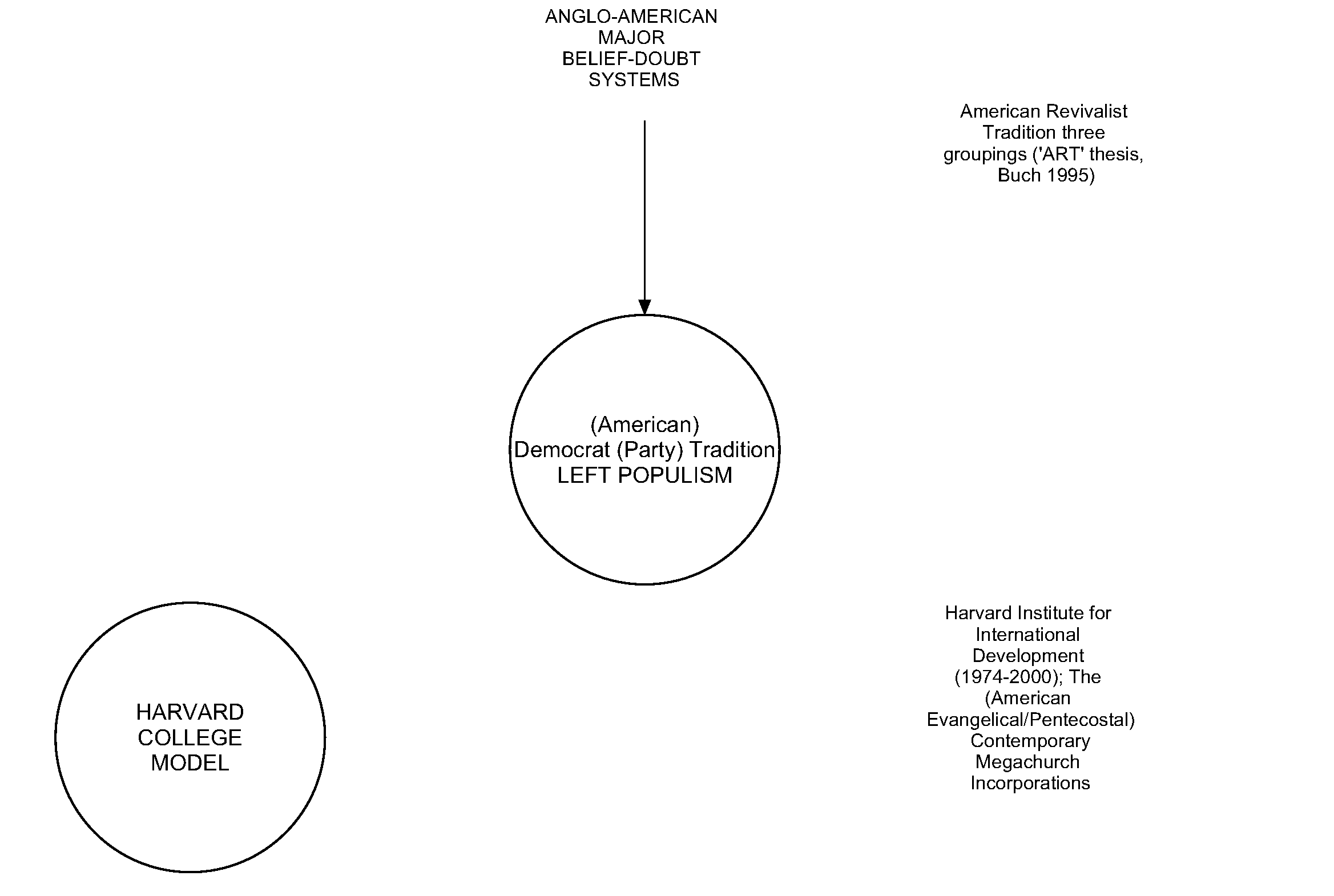

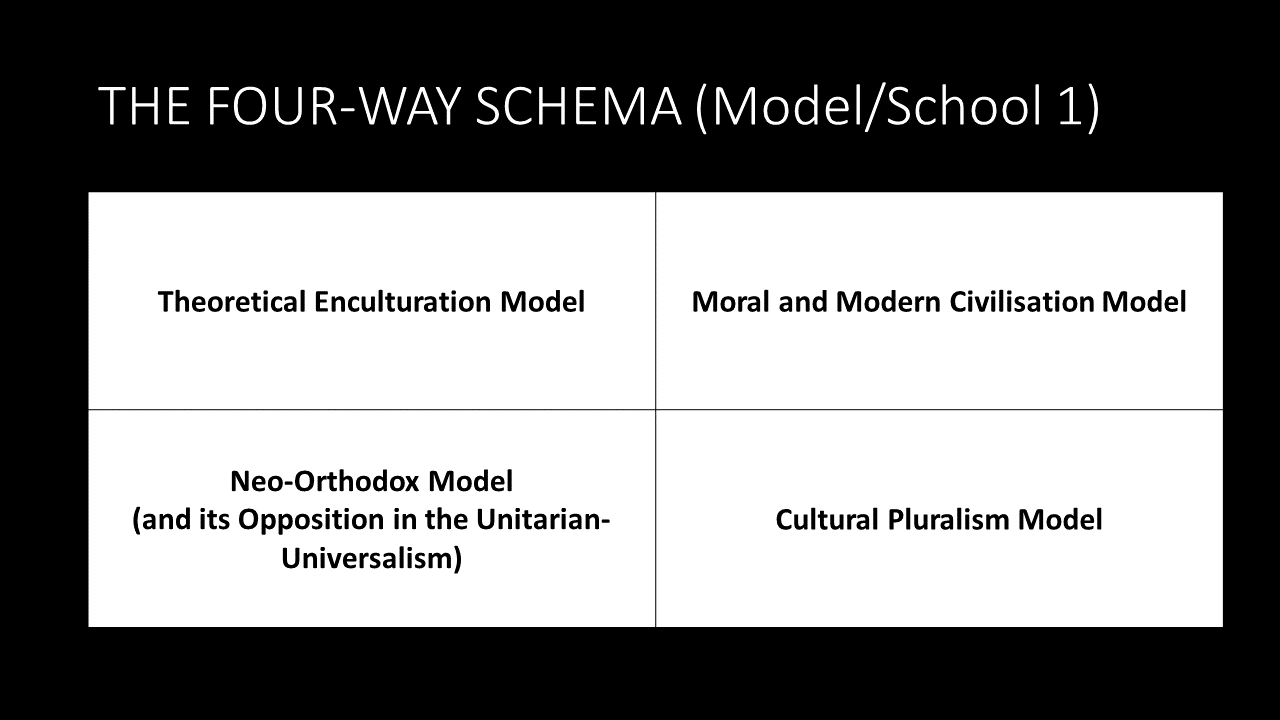

The focus here, for the concept of a new orthodoxy or neo-orthodoxy, goes to the worldviews of the Protestant and Catholic schemas, including secular expressions. So, the paper/article/blog (is there a difference today?) puts aside Orthodox Judaism and the Orthodox Christian traditions for obvious reasons, that ‘new orthodoxy’ is intellectually denied. Islam is too complex a story for orthodoxy and lies outside the specialist work of the author. In any case of ‘other religions’ and their schemas, it may well be the case that in ‘other religion’ new orthodoxies exist. The author argues that in the last few centuries the creation of new orthodoxies had come from the evolution in Protestant thought. The key understanding is the three Broad Academic Schools in Studies of Religion and 14 Academic Schools in the Philosophy of Religion

Three Broad Academic Schools in Studies of Religion and 14 Academic Schools in the Philosophy of Religion

The three main academic schools are:

1. That which centred on a general theory of religion developed by Rudolph Otto (1869 – 1937) and then later by Paul Tillich (1886 – 1965). The school had universal thought towards ‘religion’ and it is what began the larger enterprise of the academic studies of (or in) religion. The distinction between ‘academic studies’ and education broadly is made below.

2. That which centred on phenomenon, in opposition to a general theory. It was known as phenomenology of religion and developed by Mircea Eliade (1907 – 1986) but the concepts applied were generated from the leading phenomenologists and existentialists, and in particular, Edmund Husserl (1859 – 1938) and Martin Heidegger (1889 – 1976). In this regard, Paul Tillich’s ‘ultimate concern’ becomes phenomenological. This is a movement in the academic studies that predominated in the mid-twentieth century. It, nevertheless, coexisted with the education of the general theory, and arguably would not have existed without it.

3. That which centred on cultural pluralism. This is particularly the British school of Ninian Smart (1927 – 2001; Lancaster University) and John Hull (1935 – 2015; Birmingham University) in the academic studies, but a fair number of American and British philosophers of religion have been particularly important in the education: Huston Smith (Why Religion Matters, 2001) and Don Cupitt (After God: The Future of Religion, 1997) are significant. The school of ‘religious’ thinking came late; in the last few decades of the twentieth century, and is now predominant in the early 21st century. The school conjoins the phenomenological concern as cultural pluralism and the deeper skepticism of the fourth school emerges from the work of Fitzgerald and McCutcheon which focuses on the conceptual challenges of cultural pluralism.

All together the scholars across the academic studies are known as ‘religionists’. Before looking closely at the three main schools, religionists need to be distinguished with ‘religious educators’. There is a separate academic field of education which is also concerned with the academic studies of religion, but concerned with marrying these theories and concepts of religion to those of educational studies. In this regard, a few more scholars also have to be examined in relation to the Queensland history. John Dewey (1859 – 1952) was a very well-known broad educator whose views on ‘religion’ were very influential among American educators of religion. Dewey’s general theory was A Common Faith (1934), a humanistic study of religion originally delivered as the Dwight H. Terry Lectureship at Yale University. Influencing Dewey and other educators on religion was William James (1842 – 1910). James’ ‘The Will to Believe’, a lecture first published in 1896 is seminal. It brought ideas of Personal Idealism (George Holmes Howison 1834 – 1916) and of Personalism (F. C. S. Schiller 1864 – 1937) into the arrangement of American Pragmatism. Other major influences in the American Religious Education movement were Eric Erikson (1902 – 1994) for his work in the psychology of religion, and Charles Hartshorne (1897 – 2000) for his work in process philosophy. The institutions and persons in the American Religious Education movement will be considered further on.

The 14 Theological Directions from Studies of Religion and Wider Consideration of the Philosophy of Religion

The philosophic thinking has streamed between 30 to 40 theological directions and taken aboard wider consideration of contemporary philosophy of religion than what has generally been recognised in academic theological discourse in relation to the curriculum, but nevertheless has representation in 20th century education for belief and doubt, including formal programs of religious education or Christian education. Seeing how philosophical thinking streams and overlaps into the diverse theological directions, which are represented in educational programs, better provides the wide range of the educational discourse. Ranging from the earliest shift in Christian thought, following from the conventional to the less popular or less known programs, the schools of thought can range from the German Neo-Orthodox Stream to the Anglo-American Atheist-Deist Stream. At this point of the research, the focus is the scoping of Protestant Thought, bearing in mind that innovations in Catholic thought and the continuing non-innovation from the Orthodox tradition will also need to be considered. Furthermore, there are often officially-unstated influences between the three Christian broad traditions. For this reason, Catholic ‘theologians’ who are influential in Queensland, a state where Catholic thought overlapped into the thinking of broad ‘Protestant’ institutions, have to be noted. The following might not be a comprehensive listing of the theological or atheological streams, but the list is extensive and includes all major players who informed religious/Christian education:

- German Neo-Orthodox Stream – Liberal Neo-Orthodoxy

Karl Barth

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Jürgen Moltmann

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Karl Rahner |

Nouvelle théologie; Transcendental Thomism |

| Romano Guardini |

|

| Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI) |

|

- European Reformed ‘Neo-Orthodox’ Stream – Liberal Neo-Orthodoxy

Emil Brunner

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Edward Schillebeeckx |

Dominican |

- German ‘Neo-Orthodox-Process’ Stream – Liberal Neo-Orthodoxy

Wolfhart Pannenberg

- German Existentialist ‘Neo-Orthodox’ Stream – Liberal Neo-Orthodoxy

Rudolf Bultmann

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Jacques Maritain |

Existential Thomism |

- American Neo-Orthodox-Realist Stream – Liberal Neo-Orthodoxy

Reinhold Niebuhr

Richard Niebuhr

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Bernard Lonergan |

Transcendental Thomism |

| Avery Dulles |

|

- Anglican ‘Orthodox’ Stream

Richard Swinburne

John Milbank

- Anglo-American Existentialist ‘Neo-Orthodox’ Stream

Paul Tillich

John Macquarrie

- Anglo-America Process ‘Neo-Orthodox’ Stream

Paul Weiss

Charles Hartshorne

Robert Cummings Neville

John B. Cobb

- American ‘Neo-Liberal’/Universalist Stream (‘Neo-Orthodox’?)- Quietism-New Thought-Unitarian-Universalist (Christian) Stream

Langdon Gilkey

John Shelby Spong

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Hans Küng |

Rejection of Papal Infallibility; Global Ethic |

| John Courtney Murray |

Religious Liberty; Dignitatis Humanae |

- East ‘Asian’ Influence of Confucian-Buddhist-Tao-Shinto (‘Neo-Orthodox’?) Stream – Evangelical Sub-Steams 3. and 4. Radical Discipleship and Liberation

Watchman Nee

S. Song

Simon Chan (AOG)

Kwok Pui-lan (Asian feminist theology)

Chung Hyun Kyung (Asian feminist theology)

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Thomas Merton |

Trappist |

| Bernadette Roberts |

Carmelite |

| Aloysius Pieris |

Sri Lankan Jesuit |

- Anglo-American African Black Revolutionary- Africana Stream (‘Neo-Orthodox’?)

Cornel West

James H. Cone

Albert Cleage

Barney Pityana

Allan Boesak

Zephania Kameeta

- Anglo-American Quietism-New Thought-Unitarian-Universalist (Christian) Stream (the original modern Christian ‘neo-orthodoxy’?)

Parker Palmer (Quaker)

Elton Trueblood (Quaker)

Rufus Jones (Quaker)

Richard Foster (Quaker)

Emil Fuchs (Quaker)

Ernest Holmes (Christian New Thought)

Johnnie Colemon (Christian New Thought)

James Luther Adams (Unitarian-Universalist)

Webster Kitchell (Unitarian-Universalist)

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Henri Nouwen |

Catholic Quietism |

| Jean-Luc Marion |

Postmodern Phenomenology |

- Anglo-American ‘Death of God’-Secular Theology Stream (the basis for secular ‘neo-orthodoxy’?)

Harvey Cox

Don Cupitt

Paul van Buren

(14) With 30. Anglo-American Atheist-Deist Stream

Antony Flew

Brand Blanshard

There might be other ways to slice the Protestant and Catholic pie, but the schema is a very accurate worldview outlook in the widest scoping, and it has secular expression in every case.

The collapse of ‘religion’ and the rise of Studies-in-Religion

In last 40 years, the studies in religion discipline had been shaken by a broad set of criticisms for the philosophical category of ‘religion’ and ‘secular’; from a large body of literature, led by well-known scholars, Jonathan Z. Smith (1982), Wilfred Cantwell Smith (1990), Talal Asad (1993), Russell T. McCutcheon (1997, 1999, 2001, 2003, 2012 with William Arnal, 2014), Timothy Fitzgerald (2000, 2007), and Tomoko Masuzawa (2005).

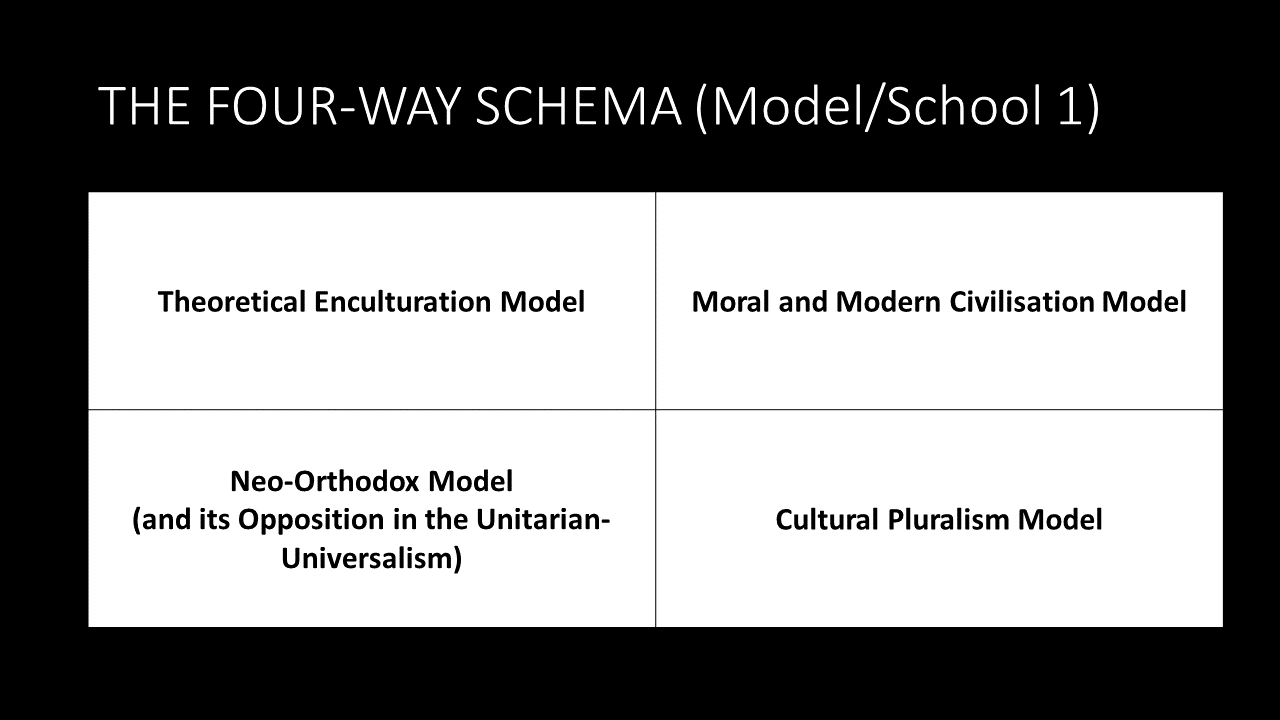

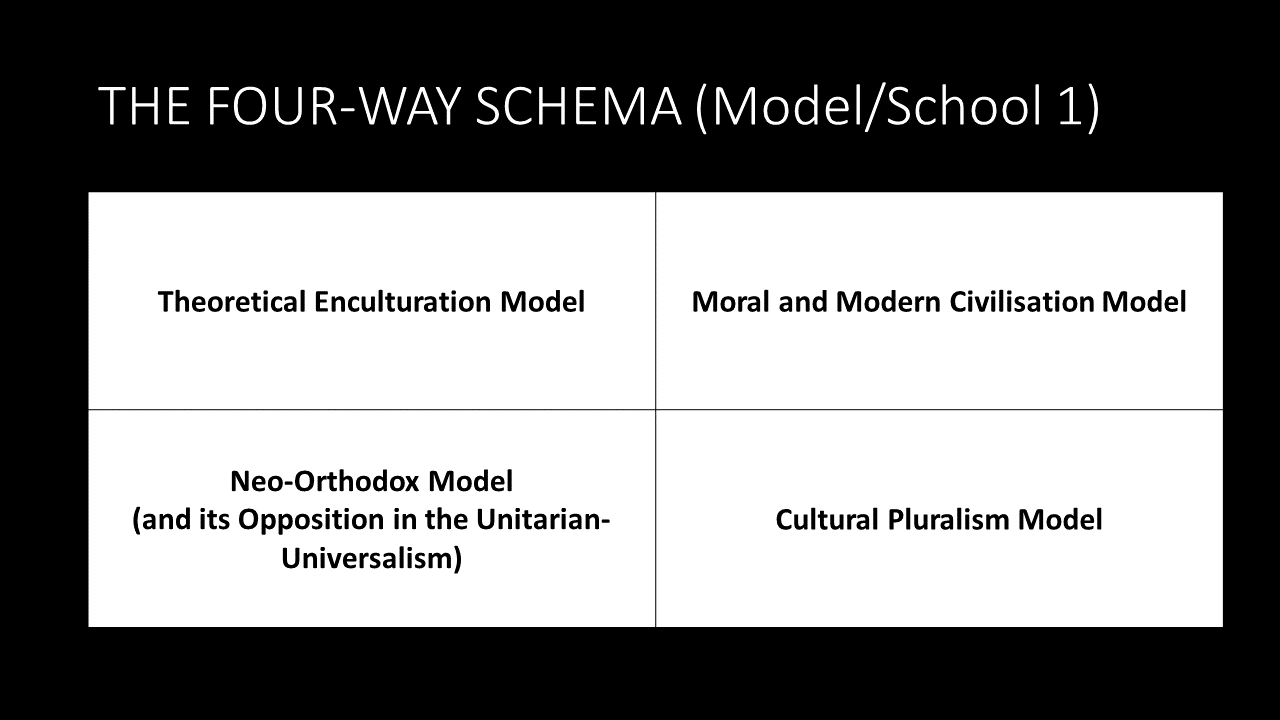

There is urgency in providing education which will defuse the explosive confusion of popular misconceptions in the history of ‘religious’/Christian instruction/‘education’.[1] Education policy makers and the general public have not caught up with the trend in higher education scholarship, and are still thinking in the outdated models of the academic discipline. If we take the last four decades as being the era of the fourth school of philosophical skepticism, there have been three previous academic schools of thought that shaped religious/Christian education: that which focused on a general theory of religion; focused on phenomenology; and focused on cultural pluralism.

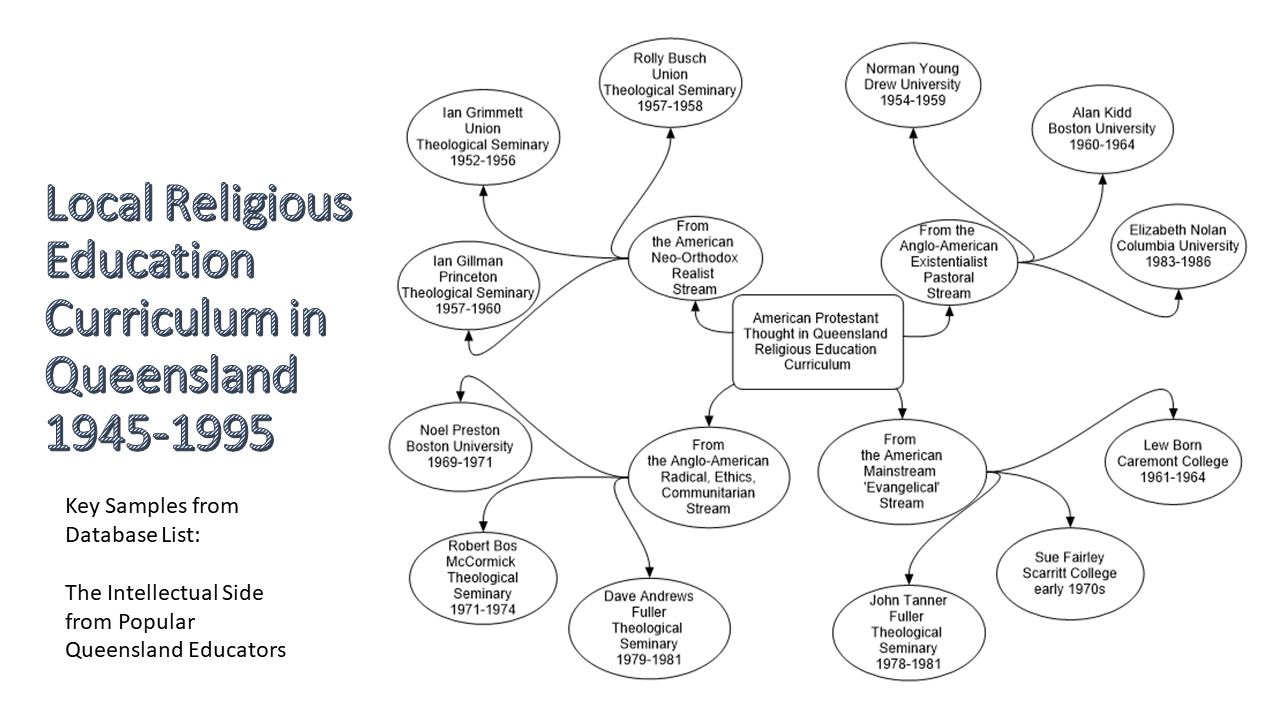

These four-way schemas are being applied in research for a book to provide the Queensland case study. This is an important and urgent analysis since the characterisation of Queensland reinforces the retrograde national narrative for outdated models of church-state relations, and will continue to do so, unless better education for faith and belief is provided. This paper will mark out the Queensland historical players and events on the pathway that shifted back and forth between religious instruction, Christian education, and religious education.

The collapse of ‘orthodoxy’ and the rise of nuanced pluralist models in monist frameworks.

At a local and regional level, as in my research on Queensland intellectual paradigms, neo-orthodoxy is translated, and can be translated, into nuanced frameworks during particular time periods, based on who lived in that local society at the time and the global waves of reading and dialogues (often overlapping):

- Colonial Period

Anti-Erastian Christianity

British Classical Education

Christian Biblicalist Education

Christian Broad-Curriculum Education

Christian Church Education

Christian Classical Education

Christian Conservative Education

Christian Secular Education

Christian Secular Modernist Education

Literary Austra-European (Colonial-Patriotic) Intellectual Education

Pre-Vatican I Catholic Education

- Federation Period

Recap: Colonial Literary Folk Education

British Classical Education

Christian Biblicalist Education

Christian Classical Education

Christian Conservative Broad-Curriculum Education

Efficient Broad-Curriculum Education

International Laborite Education

Irish Loyalist Catholic Education

Liberal-Left Evangelical Education

Vatican I Catholic Education

- Nation-Building Period

Adult and Community Education

Christian Biblicalist Education

Christian Broad-Curriculum Education

Christian Classical Education

Christian Conservative Modernist Education

Christian Modernist Education

Christian Secular Education

Conservative-Liberal Evangelical Education

Egalitarian Utilitarian Agrarian-valued Education

Irish Loyalist Catholic Education

Liberal-Left Evangelical Education

Literary Folk Education

Megachurch Prosperity Gospel Education

Modernist Social Work Education

Post-Idealist Christian Modernist Education

- Period of Mid-Century Neo-Orthodoxy and Heresy

Broad-Curriculum Education

Charismatic Christianity

Christian Broad-Curriculum Education

Christian Conservative Broad-Curriculum Education

Christian Conservative Modernist Education

Christian Modernist Liberal Education

Christian Modernist Social Work Education

Christian Secular Modernist Education

Confucianism (‘foreign’ integrated/appropriated syncretic)

Conservative Evangelical Education

Conservative-Liberal Evangelical Education

Conservative-Liberal Evangelical Indigenous Education

Diagnosis and Remedial Education

Domestic Technical Education

Educational Psychology

Fundamentalist Christianity (Creationism)

Liberal-Left Evangelical Education

Literary Modern Education

Megachurch Prosperity Gospel Education

Modernist Liberal Indigenous Education

Progress Philosophy

Renegade Laborite Education

Traditional Reformed Theology Education

- The Late Modern Period

Charismatic Christianity

Christian Conservative Broad-Curriculum Education

Christian Evangelical Skeptical Education

Christian Modernist Social Work Education

Christian Modernist-Postmodernist Liberal Education

Christian Multiculturalism and Religionist Historiography

Conservative Evangelical Education

Conservative-Liberal Evangelical Education

Conservative-Liberal Evangelical Indigenous Education

Fundamentalist Christianity (Creationism)

Liberal-Left Evangelical Education

Megachurch Prosperity Gospel Education

- The New Century

Christian Modernist Liberal Education

Christian Modernist-Postmodernist Liberal Education

Conservative-Liberal Evangelical Education

Modernist Social Work Education

Traditional Reformed Theology Education

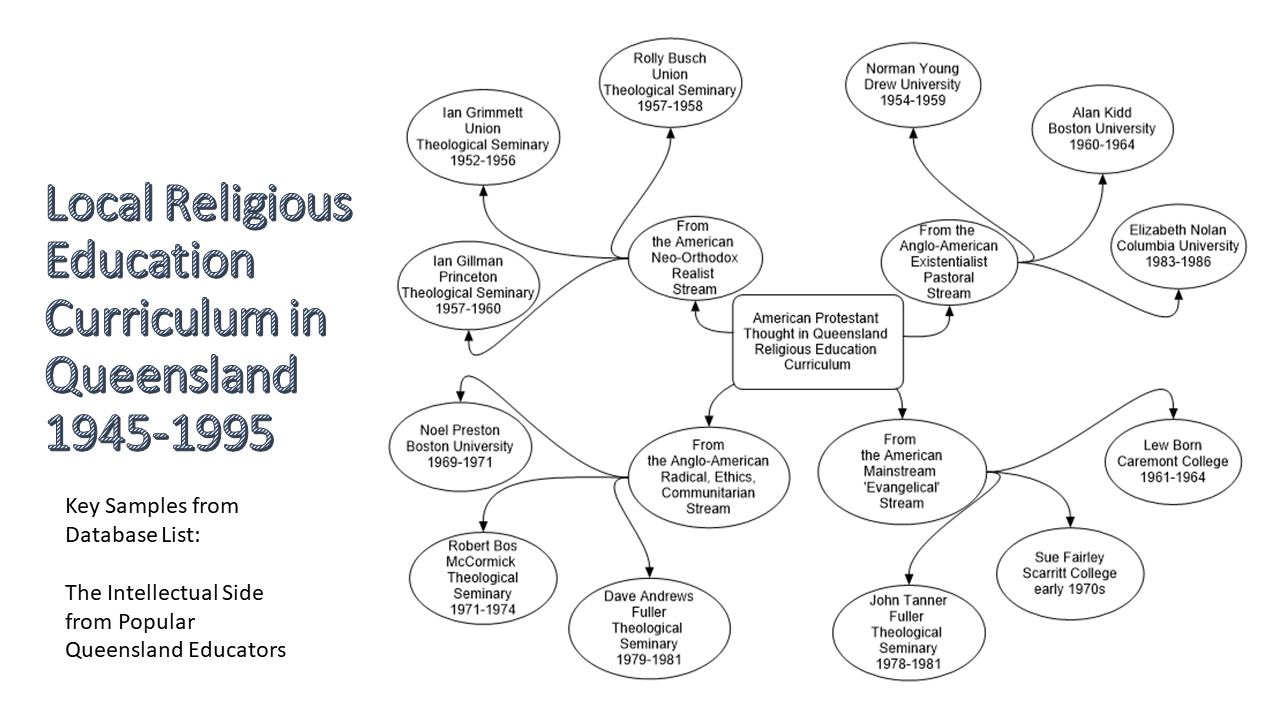

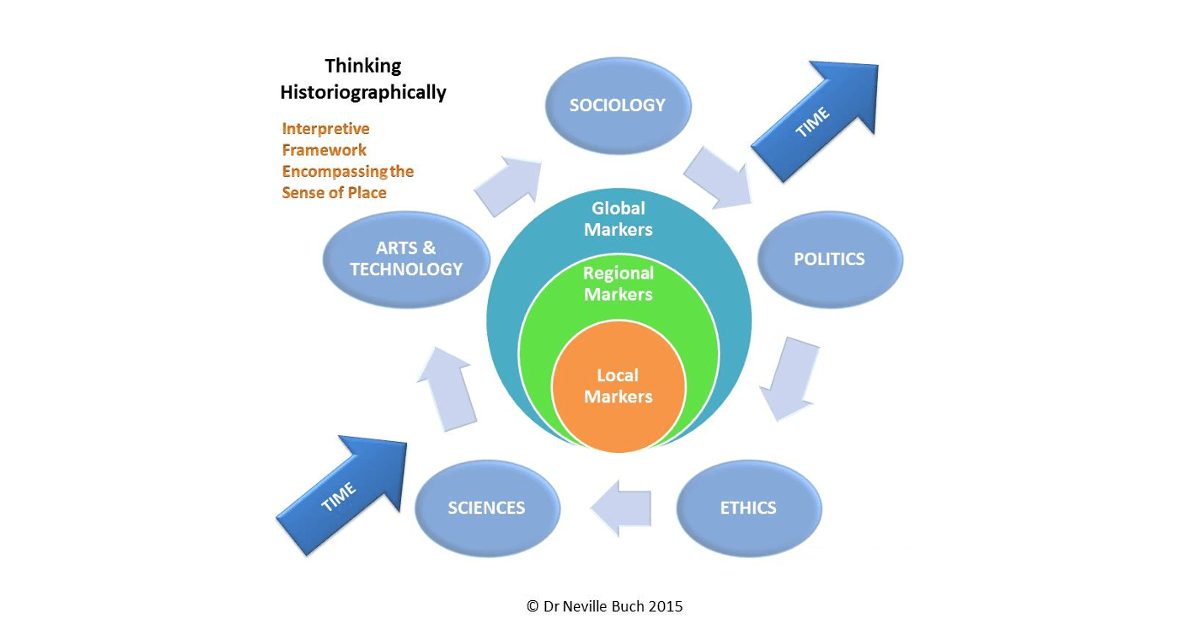

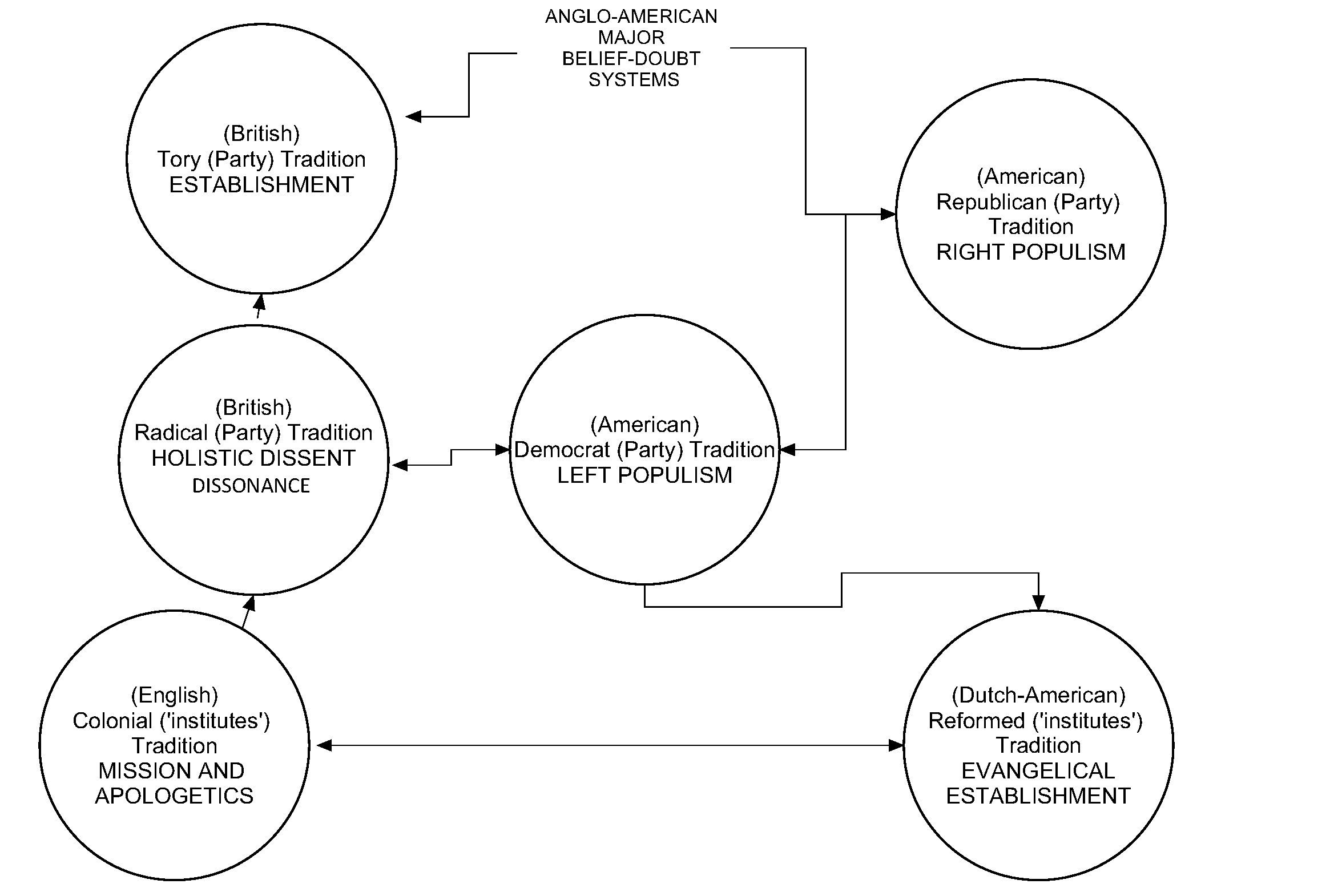

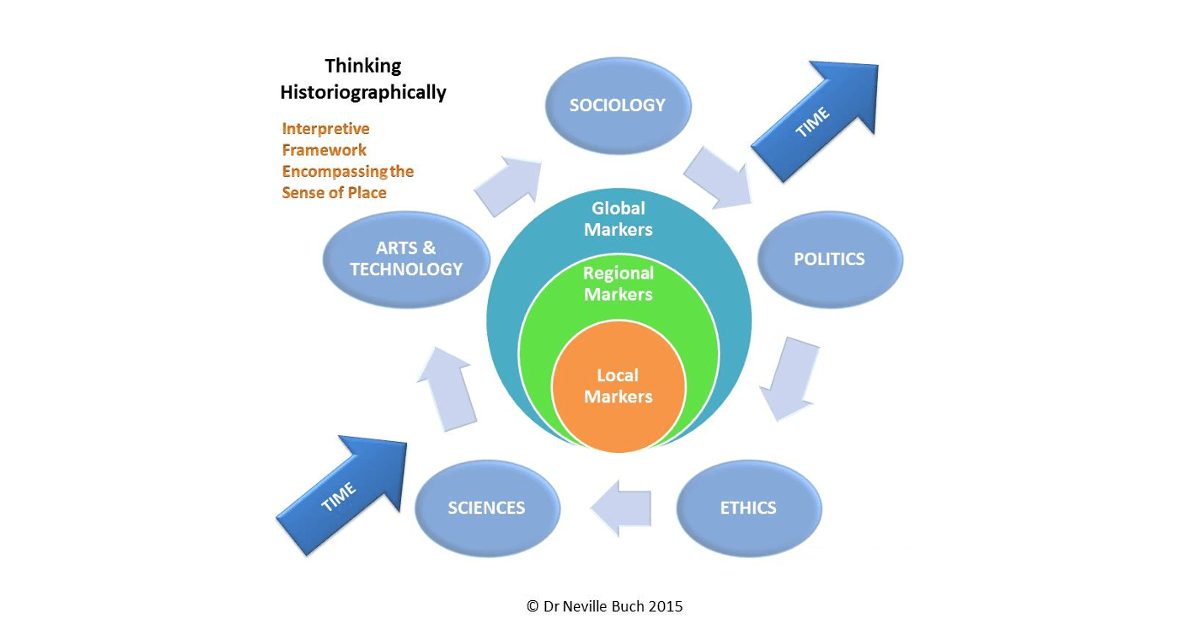

The continual reinvention of orthodox belief was a key part of the frameworks.[2] Together, it works, not as a singular belief system, but as Randall Collins’ The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change model for charting relationships of cultural and social transmissions (e.g., ‘Queensland Intellectual Scatterplot Matrix’). The historiographical model is an explanation of the global-local layering, and in my research specifically to:

- Theological Education;

- Church Education Programs; and

- Christian schooling.

On a global scale Collins (1998) argues that cultural and social transmissions happen as networks of scholars, in different types of relationships, and often beyond boundaries of the instituted ‘schools’. The traditional ‘schools’ outlook leads into the critique of Ivan Illich (1970) for “Deschooling Society”. Schools lack the capacity of correcting for the inadequacies for established and personal worldviews. With the movements of transnational histories and the dynamics of global-regional-local relations, we can see how the Queensland intellectual and educational environment was reshaped by scholars between the University of Queensland, Griffith University, and the rest of the educated society.

REFERENCES IN THE PRIMARY SOURCE RESOURCE AND BIBLIOGRAPHY ON THE TOPIC

Ackerman, J. M. (1991). Reading, Writing, and Knowing: The Role of Disciplinary Knowledge in Comprehension and Composing. Research in the Teaching of English, 25(2), 133–178. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40171186

Adam, R. (2008). Relating Faith Development and Religious Styles: Reflections in Light of Apostasy from Religious Fundamentalism. Archiv Für Religionspsychologie / Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 30, 201-231. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/23907899

Alford, R. (1961). Catholicism and Australian Politics: A Case Study of ‘Third Parties’ and Political Change. Berkeley Journal of Sociology, 6(1), 15-33. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/42888980

Almond, P. (1983). Wilfred Cantwell Smith as Theologian of Religions. The Harvard Theological Review, 76(3), 335-342. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/1509527

Almond, Philip C. & Woolcock, P. G. (1978). Dissent in Paradise : Religious Education Controversies in South Australia. Magill, S.A : Murray Park College of Advanced Education

Andrews, D. (1996). Case study in holistic mission No. 20: And now for the Good News from the “Waiters’ Union”. Transformation,13(3), 17-21. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/43054943

Arcus, M. E. (1980). Value Reasoning: An Approach to Values Education. Family Relations, 29(2), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.2307/584067

Ata, A., & Windle, J. (2007). The Role of Australian Schools in Educating Students about Islam and Muslims. AQ: Australian Quarterly, 79(6), 19-40. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/20638519

Badger, C.R. (1971). The Reverend Charles Strong and the Australian Church, Melbourne, Charles Strong Memorial Trust

Bagood, A. (2010). Complexity System and Our Catholic Faith. Angelicum, 87(1), 177-202. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/44616488

Baker, L., et al (2001). Soul, Body, and Survival: Essays on the Metaphysics of Human Persons (Corcoran K., Ed.). Ithaca; London: Cornell University Press. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctv3s8s32

Barcan, A. (1990). The Control of Schools and the Curriculum. The Australian Quarterly, 62(2), 170-177. doi:10.2307/20635582

Barcan, A. (2007). Whatever Happened to Adult Education? AQ: Australian Quarterly, 79(2), 29-40. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/20638464

Belzil, C., & Leonardi, M. (2013). Risk Aversion and Schooling Decisions. Annals of Economics and Statistics, (111/112), 35-70. doi:10.2307/23646326

Berger, Peter L (1973). The Social Reality of Religion, Harmondsworth, Penguin.

Berger, Peter L. (1998). ‘Protestantism and the quest for certainty’, The Christian Century, 115 (23), 782–796.

Black, A. (1985). The Impact of Theological Orientation and of Breadth of Perspective on Church Members’ Attitudes and Behaviors: Roof, Mol and Kaill Revisited. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 24(1), 87-100. doi:10.2307/1386277

Bouma, Gary (2007). Australian Soul : Religion and Spirituality in the 21st Century, Cambridge University Press

Bowler, Kate, and Wen Reagan (2014). ‘Bigger, Better, Louder: The Prosperity Gospel’s Impact on Contemporary Christian Worship,’ Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation, vol. 24, no. 2, pp. 186–230.

Brennan, Damien & Barry, Graeme (1997). A syllabus for religious education for Catholic schools : Brisbane Archdiocese : years 1 to 12. Brisbane Catholic Education.

Brennan, Damien & Barry, Graeme (1997). Religious education : a curriculum profile for catholic schools. Brisbane Catholic Education.

Brown, David (2006). Richard Hofstadter: An Intellectual Biography, University of Chicago Press

Bruner, Jerome S. (1977). The Process of Education, Cambridge: Harvard University Press,

Bruno-Jofré, Rosa (2022). Ivan Illich Fifty Years Later: Situating Deschooling Society in His Intellectual and Personal Journey, University of Toronto Press

Buch, Neville (1995). ‘Americanizing Queensland Protestantism’, Studying Australian Christianity 1995 Conference, Robert Menzies College, Macquarie University, July.

Buch, Neville (1995). The Significance of the American Invasion for Australian Churches: A Preliminary Examination, War’s End Conference (Queensland Studies Centre, Griffith University), University Hall, James Cook University, July.

Buch, Neville (1997). ‘‘…many distractions confronting the Church’: The Responses of Protestant Religion to Popular Culture in Queensland 1919-1969,’ Everyday Wonders Popular Culture: Past and Present’, 10th International Conference, Crest Hotel, Brisbane, June.

Buch, Neville (2007). Religion Remain a Problem. The Skeptic. Summer.

Buckley Jr., William F. (1951). God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom”, Washington, D.C: Regnery Publishing.

Burritt, A. (2022). Jesus in Schools: The Education (Religious Instruction) Act 1950. Journal for the Academic Study of Religion, 35(1), 94–111. https://doi.org/10.1558/jasr.22394

Carson, D.A. (2008). Christ and Culture Revisited, Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company

Chant, Barry (1984; revised edition). Heart of Fire: The Story of Australian Pentecostalism, Unley Park: House of Tabor.

Chant, Barry (1999), ‘The spirit of Pentecost: Origins and development of the Pentecostal movement in Australia, 1870–1939’, PhD thesis, Macquarie University.

Chant, Barry (2006). The Hallowed Touch: A Reflection on the Assembly of God Church, North Queensland, 1924-1949, Australasian Pentecostal Studies, 9, webpage

Chant, Barry (2011). The Spirit of Pentecost: The Origins and Development of the Pentecostal Movement in Australia, 1870-1939, Emeth Press.

Chappell, D. (2004). Prophetic Christian Realism and the 1960s Generation. In A Stone of Hope: Prophetic Religion and the Death of Jim Crow (pp. 67-86). University of North Carolina Press. Retrieved May 22, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/10.5149/9780807895573_chappell.7

Chilton, Hugh (2019). Evangelicals and the End of Christendom: Religion, Australia and the Crises of the 1960s, Routledge.

Clark, William (2006). Academic Charisma and the Origins of the Research University, University of Chicago Press

Clifton, Shane (2009). Pentecostalism and the Age of Interpretation: A Response, Australasian Pentecostal Studies, Issue 11. Retrieved from https://aps-journal.com/index.php/APS/article/view/96

Clifton, Shane J. (2005). An analysis of the developing ecclesiology of the Assemblies of God in Australia, PhD thesis, Australian Catholic University.

Collins, Randall (1998). The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change, Harvard University Press.

Connell, W.F.. 1980. A History of Education in the Twentieth Century World. Canberra.

Crook, Paul (2017). Intellectuals and the Decline of Religion: Essays and Reviews, Brisbane: Boolarong Press

Crown, A. (1977). The Initiatives and Influences in the Development of Australian Zionism, 1850-1948. Jewish Social Studies, 39(4), 299-322. Retrieved April 28, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/4466971

Curthoys, Ann (1991) Teaching applied history, Australian Historical Studies, 24:96, 192-197, DOI: 10.1080/10314619108595880

Davis, Glyn (2017). The Australian Idea of a University, Melbourne University Press

Davison, Graeme (1988) The Use and Abuse of Australian History, Australian Historical Studies, 23:91, 55-76, DOI: 10.1080/10314618808595790

Dayton, D. (1988). Pentecostal/Charismatic Renewal And Social Change: A Western Perspective. Transformation, 5(4), 7-13. Retrieved May 9, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/43053010

De Souza, M. (2014). Religious Identity and Plurality amongst Australian Catholics: Inclusions, Exclusions and Tensions. Journal for the Study of Religion, 27(1), 210-233. Retrieved May 6, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/24798877

Del Nevo, Matthew (2007). Pentecostalism and the Three Ages of the Church, Australasian Pentecostal Studies, Issue 10. Retrieved from https://aps-journal.com/index.php/APS/article/view/23

Dening, G. M. (1973) History as a social system, Historical Studies, 15:61, 673-685, DOI: 10.1080/10314617308595498

Deverell, Garry Worete (2018). Theology : A Trawloolway man reflects on Christian Faith, Morning Star Publishing

Dewey, John (1934, 2013). A Common Faith, Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn.

Dewey, John (1909). Moral Principles in Education, Boston : Houghton Mifflin

Dewey, John (1916). Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education, London: Macmillan and Co. Limited.

Dewey, John (1938). Experience and Education, New York: Simon and Schuster.

Dulles, Avery (1988). Models of the church (2nd ed). Dublin: Gill and Macmillan,

Dux, Monica (2021). Lapsed: Losing Your Religion is Harder Than it Looks, ABC Books

Emison, Mary (2013). Degrees for a New Generation: Marking the Melbourne Model, University of Melbourne Press

Erb, F. (1916). The Development of the Young People’s Movement. The Biblical World, 48(3), 129-192. Retrieved May 6, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/3142079

Erdozain, Dominic (2016). The soul of Doubt : the religious roots of unbelief from Luther to Marx. Oxford University Press

Evers, Colin and Gabriele Kakomski (2022). Why Context Matters in Educational Leadership: A New Theoretical Understanding, Routledge, Abingdon, Oxan, UK.

Fitzgerald, Timothy (2000). The Ideology of Religious Studies, Oxford University Press.

Fitzgerald, Timothy (2007). Discourse on Civility and Barbarity : a critical history of religion and related categories. Oxford University Press, Oxford

Fogarty, Stephen (2011). The Dark Side of Charismatic Leadership, Australasian Pentecostal Studies, 13, webpage

Freire, Paulo. (1970a). Cultural Action and Conscientization, Harvard Education Review 40, (3), 452-477.

Freire, Paulo. (1970b). Pedagogy of the Oppressed, New York: Seabury Press.

Freire, Paulo. (1972b). A letter to a theology student, Catholic Mind, 70, 1265.

Freire, Paulo. (1973). Education for Critical Consciousness, New York: Seabury Press.

Freire, Paulo. (1975). Conscientization, Geneva: World Council of Churches.

Freire, Paulo. (1976). Education, the Practice of Freedom, London: Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative.

Freire, Paulo. (1985). The Politics of Education: Culture, Power and Liberation, South Hadley: Bergin & Garvey.

Freire, Paulo. (1994). Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed, New York: Continuum.

Freire, Paulo. (1998b). Politics and Education, Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center Publications.

French, E. (1965). The Australian Tradition in Secondary Education 1814-1900. Comparative Education, 1(2), 89-103. Retrieved April 28, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/3098340

Friesen, G., & Taksa, L. (1996). Workers’ Education in Australia and Canada: A Comparative Approach to Labour’s Cultural History. Labour History, (71), 170-197. doi:10.2307/27516453

Ganter, R. (2018). Engaging with missionaries. In The Contest for Aboriginal Souls: European missionary agendas in Australia (pp. 107-146). Australia: ANU Press. Retrieved May 6, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv301dv4.9

Ganter, R. (2018). Protestants divided. In The Contest for Aboriginal Souls: European missionary agendas in Australia (pp. 23-48). Australia: ANU Press. Retrieved May 6, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv301dv4.6

Garrison, J. (1995). Deweyan Pragmatism and the Epistemology of Contemporary Social Constructivism, American Educational Research Journal, 32(4), 716-740.

Gilbert, Bennett (2020). A Personalist Philosophy of History, Routledge

Giroux, Henry (1983, co-edited with David E. Purpel). The Hidden Curriculum and Moral Education: Deception or Discovery? Berkeley: McCutchan.

Giroux, Henry and Stanley Aronowitz (1985). Education Under Siege: The Conservative, Liberal, and Radical Debate Over Schooling, Westport: Bergin and Garvey Press.

Giroux, Henry and Stanley Aronowitz (1991). Postmodern Education: Politics, Culture, and Social Criticism, Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Goldburg, P. (2008). Teaching Religion in Australian Schools. Numen, 55(2/3), 241-271. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/27643310

Gough, Austin (1962) Catholics and the free society, Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand, 10:39, 370-378, DOI: 10.1080/10314616208595243

Gowers, Ann & Scott, Roger. 1979. Fundamentals and fundamentalists : a case-study of education and policy-making in Queensland. Australasian Political Studies Association, Bedford Park, S.A.

Graeber, David (2018). Bullshit jobs (First Simon & Schuster hardcover edition). Simon & Schuster, New York

Grey, Jacqueline (2002). Torn Stockings and Enculturation: Women Pastors in the Australian Assemblies of God, Australasian Pentecostal Studies, Issue 5/6. Retrieved from https://aps-journal.com/index.php/APS/article/view/51

Gwenda Tavan (1997) ‘Good neighbours’: Community organisations, migrant assimilation and Australian society and culture, 1950–1961, Australian Historical Studies, 27:109, 77-89, DOI: 10.1080/10314619708596044

Hally, C. (1960). Student Formation in Australia. The Furrow,11(10), 662-666. Retrieved May 6, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/27657937

Handy, Robert T. (1976). A History of the Churches in the United States and Canada, Oxford at the Clarendon Press.

Handy, Robert T. (1977). A Christian America: Protestant Hopes and Historical Realities, New York. Oxford University Press.

Hannah-Jones, A. (2003). Competing Claims for Justice: Sexuality and Race at the Eighth Assembly of the Uniting Church in Australia, 1997. Journal of the History of Sexuality, 12(2), 277-304. Retrieved April 28, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/3704615

Hans, N. (1939). History of Education in the British Commonwealth of Nations. Review of Educational Research,9(4), 361-367. Retrieved April 28, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/1167565

Harris, F. (2007). Dewey’s Concepts of Stability and Precariousness in His Philosophy of Education, Education and Culture, 23(1), 38-54.

Harrison, John. (2006). The Religious Culture of Queensland: Pietism in Religious Practice, Congregationalism in Ecclesiastical Polity. Ph.D. thesis, University of Queensland.

Hayot, Eric (2021). Humanist Reason: A History, An Argument, A Plan, Columbia University Press

Hedges, Paul Michael (2021). Understanding Religion: Theories and Methods for Studying Religiously Diverse Societies, University of California Press

Hey, Sam (2011). God in the Suburbs and Beyond: The Emergence of an Australian Megachurch and Denomination. Ph.D thesis, School of Humanities, Griffith University.

Hey, Sam and Geoff Waugh (2016). Megachurches: Origins, Ministry and Prospects. Morning Star Publishing.

Higgins, Jackie (1998, 2022). Sister Girl: Reflections on Tiddalism, Identity and Reconciliation, University of Queensland Press

Hilliard, David (1991) God in the suburbs: The religious culture of Australian cities in the 1950s, Australian Historical Studies, 24:97, 399-419, DOI: 10.1080/10314619108595856

Hilliard, David (1997) Church, family and sexuality in Australia in the 1950s, Australian Historical Studies, 27:109, 133-146, DOI: 10.1080/10314619708596048

Hoffer, Eric (2002). The True Believer : thoughts on the nature of mass movements (First Perennial Modern Classics edition). Harper Perennial Modern Classics, New York

Hogan, M. (1979). Australian Secularists: The Disavowal of Denominational Allegiance. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion, 18(4), 390-404. doi:10.2307/1386363

Horne, Donald (2022). The Education of Young Donald Horne Trilogy, NewSouth Publishing

Howe, Brian & Hughes, Philip, et al. (2003). Spirit of Australia II : religion in citizenship and national life. ATF Press, Hindmarsh, SA

Hudson, Wayne (2016). Australian religious thought. Monash University Publishing, Clayton, Victoria

Hughes, Philip (1996). The Pentecostals in Australia, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, ACT.

Hutch, R. (1987). Biography, Individuality and the Study of Religion. Religious Studies, 23(4), 509-522. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/20019245

Hutchinson, Mark (1999). The New Thing God is Doing: The Charismatic Renewal and Classical Pentecostalism, Australasian Pentecostal Studies, 1, webpage

Hutchinson, Mark (2017). Australasian Charismatic Movements and the “New Reformation of the 20th Century?” Australasian Pentecostal Studies, Issue 19.

Illich, Ivan (1971). Deschooling Society. London: Calder & Boyars.

Illich, Ivan (1973). Tools for Conviviality. New York: Harper & Row.

Illich, Ivan (1974). Energy and Equity. London: Calder & Boyars.

Illich, Ivan , et al (edited,1977). Disabling Professions, New York Marion Boyars

Jagelman, Ian (1999). Church Growth: Its Promise and Problems for Australian Pentecostalism, Australasian Pentecostal Studies, Issue 1. Retrieved from https://aps-journal.com/index.php/APS/article/view/46

Jagelman, Ian (1999). Harvey Cox and Pentecostalism: A Review of Fire from Heaven, Australasian Pentecostal Studies, 1,webpage

Jones, Adrian (2011) Teaching History at University through Communities of Inquiry, Australian Historical Studies, 42:2, 168-193, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2010.531747

Jordan, Trevor L. (2007). Scapegoating Girard: Violence and the future of religion. St Mark’s Review, (202), 31-38.

Jordan, Trevor. (1992). Ethical education after Fitzgerald: return to a golden past or the end of civilisation as we know it? Social Alternatives, 11(3)

Jordan, Trevor. (1998). Studies in Religion as a Profession. Australian Religion Studies Review. 11(2)

- S. Inglis (1958) Catholic historiography in Australia, Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand, 8:31, 233-253, DOI: 10.1080/10314615808595120

KIRK, G. (2015). The Shortcomings of Abstraction (1871–2017). In The Pedagogy of Wisdom: An Interpretation of Plato’s Theaetetus (pp. 155-196). Evanston, Illinois: Northwestern University Press. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctv47wcf7.9

Kohn, Rachael (2003). The New Believers: Re-Imagining God, Harper Collins

Labaree, D. F. (1997). Public Goods, Private Goods: The American Struggle over Educational Goals. American Educational Research Journal, 34(1), 39–81. https://doi.org/10.2307/1163342

Lattke, M. (1985). Rudolf Bultmann on Rudolf Otto. The Harvard Theological Review, 78(3/4), 353-360. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/1509695

Lawry, J. (1967). The Development of a National System of Education in New South Wales. History of Education Quarterly,7(3), 349-356. doi:10.2307/367177

Lecompte, M. D. (2014). Collisions of culture: Academic culture in the neoliberal university. Learning and Teaching: The International Journal of Higher Education in the Social Sciences, 7(1), 57–78. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24717955

Leigh Boucher & Michelle Arrow (2016) ‘Studying Modern History gives me the chance to say what I think’: learning and teaching history in the age of student-centred learning, History Australia, 13:4, 592-607, DOI: 10.1080/14490854.2016.1249274

Loos, N. (1991). From Church to State: The Queensland Government Take-Over of Anglican Missions In North Queensland. Aboriginal History, 15(1/2), 73-85. Retrieved April 28, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/24046403

Macintyre, Stuart (2009) The Poor Relation: Establishing the Social Sciences in Australia, 1940–1970, Australian Historical Studies, 40:1, 47-62, DOI: 10.1080/10314610802663019

Macklin, Michael (1972). To Deschool Society, Cold Comfort, December 1972.

Macklin, Michael (1975). Those Misconceptions are not Illich’s, Educational Theory, 25 (3), 323-329

Macklin, Michael (1976). When Schools are Gone: A Projection of the Thought of Ivan Illich, St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Maddox, Marion (2001). For God and Country: Religious Dynamics in Australian Federal Politics, Canberra: Parliament of Australia

Maddox, Marion (2005). God Under Howard: The Rise of The Religious Right in Australian Politics, Sydney: Allen & Unwin

Maddox, Marion (2014). Taking God to School: The End of Australia’s Egalitarian Education, Allen & Unwin

Malcolm Vick (1992) Community, state and the provision of schools in mid‐nineteenth century South Australia, Australian Historical Studies, 25:98, 53-71, DOI: 10.1080/10314619208595893

Marginson, S. (1997). Imagining Ivy: Pitfalls in the Privatization of Higher Education in Australia. Comparative Education Review, 41(4), 460-480. Retrieved April 28, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/1189004

Marginson, Simon (2016). Higher Education and the Common Good. Melbourne University Publishing

Marsden, George M. (1987). Reforming Fundamentalism. Fuller Seminary and the New Evangelicalism, Grand Rapids: William B. Eermanns Publishing Company.

Marsden, W. E. (2000). Geography and Two Centuries of Education for Peace and International Understanding. Geography, 85(4), 289–302. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40573474

Marti, Gerardo (2020). American Blindspot: Race, Class, Religion, and the Trump Presidency, London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Marty, Martin E. (1970). Righteous Empire. The Protestant Experience, New York:The Dial Press.

Mavor, Ian. 1977. Religious education : its nature and aims : a statement of principles underlying the development work of the Religious Education Curriculum Project. Queensland. Dept. of Education. Religious Education Curriculum Project. Select

MAYRL, D. (2011). Administenng Secularization: Religious Education in New South Wales since 1960. European Journal of Sociology / Archives Européennes De Sociologie / Europäisches Archiv Für Soziologie, 52(1), 111-142. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/43282174

McCutcheon, Russell T (1997). Manufacturing Religion : the discourse on sui generis religion and the politics of nostalgia. Oxford University Press, New York

McCutcheon, Russell T. (2014). Entanglements: Marking Place in the Field of Religion, Equinox Publishing.

McDonagh, S. (2006). The Australian Church and Climate Change. The Furrow, 57(1), 48-53. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/27665281

McLoughlin, William G. (1987). Revivals, Awakenings and Reform: An Essay on Religion and Social Change in America 1607-1977, The University of Chicago Press.

Mead, Sidney E. (1975). The Nation with the Soul of a Church, New York: Harper and Row.

Meyer, C. (2000). “What a Terrible Thing It Is to Entrust One’s Children to Such Heathen Teachers”: State and Church Relations Illustrated in the Early Lutheran Schools of Victoria, Australia. History of Education Quarterly, 40(3), 302-319. doi:10.2307/369555

Miller, R. (1939). Is Temple a Realist? The Journal of Religion,19(1), 44-54. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/1197939

Mol, H. (1974). The Sacralization of the Family With Special Reference to Australia. Journal of Comparative Family Studies, 5(2), 98-108. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/41600888

Mol, J. (1969). Rites of Passage in Australia. The Australian Quarterly, 41(3), 64-74. doi:10.2307/20634302

Montessori, Maria (1914). Dr. Montessori’s Own Handbook, New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company.

Montessori, Maria (1949). The Absorbent Mind, Madras: Theosophical Publishing House.

Montessori, Maria (Translated by Anne E. George,1912). The Montessori Method: Scientific Pedagogy as Applied to Child Education in ‘The Childhood Houses’ with Additions and Revisions by the Author, New York: Frederick A. Stokes Company.

Montessori, Maria (Translated by Barbara B. Carter, 1936). The Secret of Childhood, New York: Longmans, Green & Co. Inc.

Montessori, Maria (Translated by Mary A. Johnstone, 1948). The Discovery of the Child, Madras: Kalakshetra Publications Press.

Mulder, Mark & Marti, Gerardo. (2020). The Glass Church: Robert H. Schuller, the Crystal Cathedral, and the Strain of Megachurch Ministry, Rutgers University Press

Murphy, Kate (2015) ‘In the Backblocks of Capitalism’: Australian Student Activism in the Global 1960s, Australian Historical Studies, 46:2, 252-268, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2015.1039554

Murray, Iain H. (1988) Australian Christian Life From 1788: An Introduction and an Anthology, Edinburgh: The Banner of Truth Trust.

Myers, Benjamin (2012). Christ the Stranger: The Theology of Rowan Williams, t & t Clark.

Nethersole, Reingard (2015). Twilight of the Humanities: Rethinking (Post)Humanism with J.M. Coetzee. Symplokē, 23(1-2), 57-73. doi:10.5250/symploke.23.1-2.0057

Niebuhr, Reinhold (1932). Moral Man and Immoral Society: A Study in Ethics and Politics, Charles Scriber’s Sons [Rev. Ed. Westminster John Knox, 2001].

Niebuhr, Richard (1937). The Kingdom of God in America

Niebuhr, Richard (1951). Christ and Culture, New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers

Niebuhr, Richard (1963). The Responsible Self : An Essay in Christian Moral Philosophy

Noddings, Nel (2013). Education and Democracy in the 21st Century, Teachers’ College Press

Noddings, Nel (1984). Caring: A Feminine Approach to Ethics and Moral Education, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Noddings, Nel (1996). Stories and Affect in Teacher Education, Cambridge Journal of Education, 26 (3).

Noddings, Nel (1999). Justice and Caring: The Search for Common Ground in Education, Teachers College Press, New York.

Noddings, Nel (2005). Identifying and Responding to needs in Teacher Education, Cambridge Journal of Education, 35 (2).

Noddings, Nel (2005). What does it mean to Educate the WHOLE child? Educational Leadership, 63 (1).

Noel Pearson (2021). Mission: Essays, Speeches & Ideas, Black Inc.

Nolan, Carolyn & Stuartholme Convent of the Sacred Heart (Brisbane, Qld.) (1995). Ribbons, beads and processions : the foundation of Stuartholme. Stuartholme Parents and Friends Association, Toowong, Qld

Nuyen, A. (2001). Realism, Anti-Realism, and Emmanuel Levinas. The Journal of Religion, 81(3), 394-409. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/1206402

Nye, Adele, and Marnie Hughes-Warrington, Jill Roe, Penny Russell, Mark Peel, Desley Deacon, Amanda Laugeson & Paul Kiem (2009). Historical Thinking in Higher Education, History Australia, 6:3, 73.1-73.16, DOI: 10.2104/ha090073

O’Brien, Anne (1993) ‘A church full of men’: Masculinism and the church in Australian history, Australian Historical Studies, 25:100, 437-457, DOI: 10.1080/10314619308595925

O’Brien, Anne (1996) The case of the ‘cultivated man’: Class, gender and the church of the establishment in interwar Australia, Australian Historical Studies, 27:107, 242-256, DOI: 10.1080/10314619608596012

O’Brien, Anne (1997) Sins of Omission? Women in the history of Australian religion and religion in the history of Australian women. A reply to Roger Thompson, Australian Historical Studies, 27:108, 126-133, DOI: 10.1080/10314619708596032

O’Brien, Anne (2002) Historical overview spirituality and work Sydney women, 1920–1960, Australian Historical Studies, 33:120, 373-388, DOI: 10.1080/10314610208596226

O’Farrell, Patrick (1977) Historians and religious convictions, Historical Studies, 17:68, 279-298, DOI: 10.1080/10314617708595552

Ono, A. (2012). You gotta throw away culture once you become Christian: How ‘culture’ is Redefined among Aboriginal Pentecostal Christians in Rural New South Wales. Oceania, 82(1), 74-85. Retrieved April 27, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/23209618

Osborn, D. (2010). CHAPTER THREE: Resisting the State: Christian Fundamentalism and A Beka. Counterpoints, 376, 35-45. Retrieved April 28, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/42980731

Otto, R., & Almond, P. (1984). Buddhism and Christianity: Compared and Contrasted. Buddhist-Christian Studies, 4, 87-101. doi:10.2307/1389938

Pals, Daniel (2022). Ten Theories of Religion, Oxford University Press.

Perry, B. (2011). Universities and Cities: Governance, Institutions and Mediation. Built Environment (1978-), 37(3), 244–259. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23290044

Petersen, D. (1999). Missions in the twenty-first century: Toward a methodology of Pentecostal compassion. Transformation, 16(2), 54-59. Retrieved May 9, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/43053095

Phillips, R. (1978). John Dewey Visits the Ghetto. The Journal of Negro Education, 47(4), 355-362. doi:10.2307/2295000

Phillips, Walter (1981). Defending “a Christian country” : churchmen and society in New South Wales in the 1880s and after. University of Queensland Press, St. Lucia, Qld

Piaget, Jean (1953). Logic and Psychology, Manchester: Manchester University Press,

Piaget, Jean (1969). The Mechanisms of Perception, New York: Basic Books.

Piaget, Jean (1977). The Grasp of Consciousness: Action and concept in the young child, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Pietsch, Tamson (2015). Empire of Scholars : Universities, Networks and the British Academic World, 1850-1939. Manchester University Press, Oxford

Piggin, Stuart & Linder, Robert D., (author.) & Scalmer, Sean, (series editor.) & Monash University Publishing, (publisher.) (2018). The Fountain of Public Prosperity : evangelical Christians in Australian history 1740 – 1914. Monash University Publishing, Clayton, Vic

Pizmony-Levy, O. (2011). Bridging the Global and Local in Understanding Curricula Scripts: The Case of Environmental Education. Comparative Education Review, 55(4), 600–633. https://doi.org/10.1086/661632

Rademaker, Laura; Noelani Goodyear-Ka’opua, April K. Henderson (2022). Found in Translation : Many Meanings on a North Australian Mission, University of Hawai’i Press.

Radford, M. (2007). Passion and Intelligibility in Spiritual Education, British Journal of Educational Studies, 55 (1), 21-36.

Riches, Tanya (2010). Next Generation Essay: The Evolving Theological Emphasis of Hillsong Worship (1996–2007), Australasian Pentecostal Studies, Issue 13. Retrieved from https://aps-journal.com/index.php/APS/article/view/108

Ringma, Charles; Chadwick, Remy. (2017). Three Graces for a Word of Truth. The church’s calling in a troubled world: the grand design and fragile engagement. Hawthorn, VIC: Zadok Institute for Christianity and Society.

Rocha, Cristina, Mark P. Hutchinson and Kathleen Openshaw (edited, 2020). Australian Pentecostal and Charismatic Movements: Arguments from the Margins, Leiden: Brill.

Rouse, Joseph (2015). Articulating the World: Conceptual Understanding and the Scientific Image, The University of Chicago Press

Rutland, Suzanne D. (2018) A Celebratory History of Queensland Jewry, History Australia, 15:1, 202-204, DOI: 10.1080/14490854.2018.1416547

Saperstein, D. (2003). Public Accountability and Faith-Based Organizations: A Problem Best Avoided. Harvard Law Review,116(5), 1353-1396. doi:10.2307/1342729

Shay, Marnee and Rhonda Oliver (edited, 2021). Indigenous Education in Australia: Learning and Teaching for Deadly Futures, 1st Edition, Routledge, Abingdon, Oxon, UK.

Sherlock, Peter (2008) ‘Leave it to the Women’ The Exclusion of Women from Anglican Church Government in Australia, Australian Historical Studies, 39:3, 288-304, DOI: 10.1080/10314610802263299

Sherlock, Peter (2018) Book Review: ‘Our Principle of Sex Equality’: The Ordination of Women in the Congregational Church in Australia 1927–1977, Australian Historical Studies, 49:3, 428-429, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2018.1495153

Sider, Ronald (1982). Lifestyles in the Eighties. An Evangelical Commitment to Simple Lifestyles, Philadelphia: Westminster Press.

Smith, Jonathan Z. (1982). Imagining Religion: From Babylon to Jonestown, The University of Chicago Press

Smith, Philippa Mein (2018) Locating Australia? How students view Australia’s region, History Australia, 15:2, 216-235, DOI: 10.1080/14490854.2018.1452161

Spearritt, G. (1995). Don Cupitt: Christian Buddhist? Religious Studies, 31(3), 359-373. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/20019757

Sperry, William L. (1945). Religion in America, Cambridge University Press.

Stacey, Jeff (2004). Does the Historical Phenomenon of Revival Have a Recognisable ’Pattern’ of Characteristic, Observable Features? Australasian Pentecostal Studies, Issue 8. Retrieved from https://aps-journal.com/index.php/APS/article/view/71

Stanczak, G. (2006). Engaged Spirituality: Social Change and American Religion. New Brunswick, New Jersey; London: Rutgers University Press. Retrieved May 9, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt5hj8ft

Stark, Rodney and William S. Bainbridge (1987). A Theory of Religion, New York, Peter Lang.

Starr, I. (1954). John Dewey, My Son, and Education for Human Freedom, The School Review, 62 (4), 204-212.

Starr, J. P. (2019). To improve the curriculum, engage the whole system. The Phi Delta Kappan, 100(7), 70–71. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26677377

Stauberg, Michael , Carole M. Cusask, Stuart A. Wright (edited, 2022). The Demise of Religion: How Religions End, Die, or Dissipate, Bloomsbury Publishing PL

Steiner, Rudolf (1907). The Education of the Child, New York: Rudolf Steiner Publications, Inc.

Stevens, Bruce (2006). “Why Feel Bad?” A Theory of Affect and Pentecostal Spirituality, Australasian Pentecostal Studies, 9, webpage

Swain, Shurlee (2005) Do You Want Religion with That? Welfare History in a Secular Age, History Australia, 2:3, 79.1-79.8, DOI: 10.2104/ha050079

Sweet, William Warren (1965). Revivalism in America, Gloucester: Peter Smith.

Szasz, Ferenc Morton (1982). The Divided Mind of Protestant America 1880-1930, Alabama: The University of Alabama Press.

Tacey, David (2000). ReEnchantment: The New Australian Spirituality, Sydney: Harper Collins

Tacey, David (2004). The Spirituality Revolution: The emergence of contemporary spirituality, London: Routledge

Tacey, David (2015). Religion as Metaphor: Beyond Literal Belief, London: Routledge

Tauber, Zvi. (2006). Aesthetic Education for Morality: Schiller and Kant. Journal of Aesthetic Education, 40(3), 22-47. Retrieved April 28, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/4140178

Teese, Richard (2000). Academic Success and Social Power: Examinations and Inequality, Melbourne University Press

Thompson, Roger C. (1997) Women and the significance of religion in Australian history, Australian Historical Studies, 27:108, 118-125, DOI: 10.1080/10314619708596031

Tobin, Susan M. (1987). Catholic Education in Queensland. Conference of Catholic Education, Queensland, Brisbane.

Truman, T. (1958). Church And State: The Teaching Of The Catholic Church On Intervention In Politics. The Australian Quarterly, 30(4), 35-43. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/20694699

Unnamed. (1975-1979). Catholic education : Policy and Practice. Catholic Education Council (Brisbane, Qld.).

Unnamed. (1983-1987). Religious Education: Teaching Approaches. Department of Education Queensland.

Unnamed. (1984). Religious Education Curriculum Project 1975-1983 : project report. Queensland. Department of Education. Curriculum Branch .

Unnamed. (1986). Religious Education: Teachers Notes – Years. Department of Education Queensland.

Unnamed. (1990). Growing together in faith : religious education content for Years P – 7. Catholic Education Office, Rockhampton, Qld.

Unnamed. (1998). Religious education in state schools : coordinators handbook. Brisbane Catholic Education.

Vondey,Wolfgang (2011).A Review Symposium on: Wolfgang Vondey, Beyond Pentecostalism, Australasian Pentecostal Studies, 13, webpage

Vygotsky, Lev (Russian edition from 1982). The Collected Works of L. S. Vygotsky, Soviet Union, including, Volume 3, Chapter 15: The Historical Meaning of the Crisis in Psychology: A Methodological Investigation (Plenum Press, 1987).

Walker, A. (1961). The Church in the New Australia. The Australian Quarterly, 33(3), 70-80. doi:10.2307/20633722

Wallis, Jim (1995). The Soul of Politics: Beyond “Religious Right” and “Secular Left”, Harcourt Brace.

Walter Phillips (1971) Australian Catholic historiography: Some recent issues, Historical Studies, 14:56, 600-611, DOI: 10.1080/10314617108595446

Warhurst, J. (1976). United States’ Government Assistance to the Catholic Social Studies Movement, 1953-4. Labour History, (30), 38-41. doi:10.2307/27508215

Warhurst, J. (2012). Religion and the 2010 Election: Elephants in the room. In Simms M. & Wanna J. (Eds.), Julia 2010: The caretaker election (pp. 303-312). ANU Press. Retrieved May 6, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt24h9hm.30

Weber, B. (2011). Design and its discontents. Synthese, 178(2), 271-289. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/41477275

Weiler, Peter T. (2000). Pentecostal Postmodernity? An Unexpected Application of Grenz’s Primer on Postmodernism, Australasian Pentecostal Studies, 2/3, webpage

Werpehowski, William (2002). American Protestant Ethics and the Legacy of H. Richard Niebuhr, Georgetown University Press

Wieneke, Peter, Phillips, Ian. 1979. Study of Christianity : Religious Education Curriculum for Years 11, 12. Villanova College. Select

Wild, M. (2015). Liberal Protestants and Urban Renewal. Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation, 25(1), 110–146. https://doi.org/10.1525/rac.2015.25.1.110

Williams, Stafford. 1986. R.E. lesson plans for secondary schools. Youth Concern Ltd, Gold Coast, Qld. Select

Wuthnow, R. (2004). Public Policy and Civil Society. In Saving America?: Faith-Based Services and the Future of Civil Society (pp. 286-310). Princeton; Oxford: Princeton University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctt7s2hm.13

Wyatt, T. (2009). The Role of Culture in Culturally Compatible Education. Journal of American Indian Education, 48(3), 47–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24398754

ENDNOTES

[1] B.01 Education for Faith & Belief: ‘Education for Faith and Belief’: The Problem of Popular Misconceptions in Queensland, 2022 Australian Historical Association, Geelong, Victoria, Australia, Thursday 30 June 2022.

[2] Historical Sociology of/for Christian/Religious Education in Queensland: Mapping 1859-2022 and Beyond, 2022 Australian Sociological Association Conference (TASA), University of Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, Wednesday 30 November 2022.

by Neville Buch | Mar 1, 2021 | Educationalist History

‘EDUCATION FOR FAITH AND BELIEF’: RELIGIOUS INSTRUCTION, RELIGIOUS EDUCATION, AND CHRISTIAN EDUCATION IN QUEENSLAND 1875-2020

In order to investigate, with any intelligence, the history of religious instruction, religious education, and Christian education in Queensland, between the years 1875-2020 (what was taught under the state as ‘education for faith and belief’), it necessary to understand the practical applications of different concepts. The educational structure in this work is an analysis of the Nolan-Buch’s Table ‘Education for Faith & Belief’ (see Appendix 1, at the end of the document). Quite simply, it is an argument is that, in the sphere of ‘religion’ and Christian belief, the typology in the education (broadly understood) covers six distinct sets of activities: religious instruction, evangelism, Sunday school, Youth movement events, religious education, and studies in religion. There are three philosophical schools of thought in the sphere of ‘religion’ and Christian belief, which generated the academic studies of religion as higher education, and which then translates as ‘religious education’ (broadly speaking, at this point). Furthermore, the philosophic thinking had streamed in 30 theological directions. It is necessary, to understand the history, to hold the process together across tertiary, secondary, and primary levels of education. Although the uneducated populist thinker will object, the dynamic is significantly top-down; however, the process does also have a feedback loop where local influences feedback the global discourse with local character added.

The top-down process is dominant for the very reason it is ‘historically given’, even as it is not epistemological ‘given’ (Sellars). The concept of ‘religion’ is contentiously given, and so with the three schools of academic studies, a fourth one has been emerging in the last twenty years which argues that the category of ‘religion’ is falsely understood or misconceived (Fitzgerald 2000, and 2007 a, b). Timothy Fitzgerald argues that historically, prior to modernity, ‘religion’ and ‘Christian Truth’ are concurrently understood fully. Although modernity had come to a different semantics (a vague private sphere), the users of the category will often infer (perhaps unknowingly) a privilege to Christian Truth or simply reflect such belief. Fitzgerald’s thesis, supported by many other scholars of similar arguments (McCutcheon 1997, 2019), makes the case for this history more urgent. The three main academic schools translate into the other schooling as 1) the basic idea and practise in unchurched Christian ‘dogma’; 2) churched instruction into schools; and 3) the education known as ‘religion’. At this point, it will be clear that the history has been a matter of contentious theories and schemas, and, importantly, that the three approaches in education or instruction (‘propaganda’ in the legitimating meaning of the old Catholic Church) are never tight compartments; concepts overlap in practice. The skepticism that the state mechanisms has not taught anything more than education or propaganda for the Christian faith and belief will be returned to at the end, and considers what could be an alternative for the space of belief and doubt in a large scope.

Academic Schools in Studies of Religion and Philosophy of Religion

The three main academic schools are:

- That which centred on a general theory of religion developed by Rudolph Otto (1869 – 1937) and then later by Paul Tillich (1886 – 1965). The school had universal thought towards ‘religion’ and it is what began the larger enterprise of the academic studies of (or in) religion. The distinction between ‘academic studies’ and education broadly is made below.

- That which centred on phenomenon, in opposition to a general theory. It was known as phenomenology of religion and developed by Mircea Eliade (1907 – 1986) but the concepts applied were generated from the leading phenomenologists and existentialists, and in particular, Edmund Husserl (1859 – 1938) and Martin Heidegger (1889 – 1976). In this regard, Paul Tillich’s ‘ultimate concern’ becomes phenomenological. This is a movement in the academic studies that predominated in the mid-twentieth century. It, nevertheless, coexisted with the education of the general theory, and arguably would not have existed without it.

- That which centred on cultural pluralism. This is particularly the British school of Ninian Smart (1927 – 2001; Lancaster University) and John Hull (1935 – 2015; Birmingham University) in the academic studies, but a fair number of American and British philosophers of religion have been particularly important in the education: Huston Smith (Why Religion Matters, 2001) and Don Cupitt (After God: The Future of Religion, 1997) are significant. The school of ‘religious’ thinking came late; in the last few decades of the twentieth century and is now predominant in the early 21st The school conjoins the phenomenological concern as cultural pluralism and the deeper skepticism of the fourth school emerges from the work of Fitzgerald and McCutcheon which focuses on the conceptual challenges of cultural pluralism.

All together the scholars across the academic studies are known as ‘religionists’. Before looking closely at the three main schools, religionists need to be distinguished with ‘religious educators’. There is a separate academic field of education which is also concerned with the academic studies of religion, but concerned with marrying these theories and concepts of religion to those of educational studies. In this regard, a few more scholars also have to be examined in relation to the Queensland history. John Dewey (1859 – 1952) was a very well-known broad educator whose views on ‘religion’ were very influential among American educators of religion. Dewey’s general theory was A Common Faith (1934), a humanistic study of religion originally delivered as the Dwight H. Terry Lectureship at Yale University. Influencing Dewey and other educators on religion was William James (1842 – 1910). James’ ‘The Will to Believe’, a lecture first published in 1896 is seminal. It brought ideas of Personal Idealism (George Holmes Howison 1834 – 1916) and of Personalism (F. C. S. Schiller 1864 – 1937) into the arrangement of American Pragmatism. Other major influences in the American Religious Education movement were Eric Erikson (1902 – 1994) for his work in the psychology of religion, and Charles Hartshorne (1897 – 2000) for his work in process philosophy. The institutions and persons in the American Religious Education movement will be considered further on.

The Theological Directions from Studies of Religion and Wider Consideration of the Philosophy of Religion

The philosophic thinking has streamed in 30 theological directions and taken aboard wider consideration of contemporary philosophy of religion than what has generally been recognised in academic theological discourse in relation to the curriculum, but nevertheless has representation in 20th century education for belief and doubt, including formal programs of religious education or Christian education. Seeing how philosophical thinking streams and overlaps into the diverse theological directions, which are represented in educational programs, better provides the wide range of the educational discourse. Ranging from the earliest shift in Christian thought, following from the conventional to the less popular or less known programs, the schools of thought can range from the German Neo-Orthodox Stream to the Anglo-American Atheist-Deist Stream. At this point of the research, the focus is the scoping of Protestant Thought, bearing in mind that innovations in Catholic thought and the continuing non-innovation from the Orthodox tradition will also need to be considered. Furthermore, there are often officially-unstated influences between the three Christian broad traditions. For this reason, Catholic ‘theologians’ who are influential in Queensland, a state where Catholic thought overlapped into the thinking of broad ‘Protestant’ institutions, have to be noted. The following might not be a comprehensive listing of the theological or atheological streams, but the list is extensive and includes all major players who informed religious/Christian education:

- German Neo-Orthodox Stream

Karl Barth

Dietrich Bonhoeffer

Jürgen Moltmann

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Karl Rahner |

Nouvelle théologie; Transcendental Thomism |

| Romano Guardini |

|

| Joseph Ratzinger (Pope Benedict XVI) |

|

- European Reformed ‘Neo-Orthodox’ Stream

Emil Brunner

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Edward Schillebeeckx |

Dominican |

| |

|

- German ‘Neo-Orthodox-Process’ Stream

Wolfhart Pannenberg

- German Existentialist ‘Neo-Orthodox’ Stream

Rudolf Bultmann

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Jacques Maritain |

Existential Thomism |

- American Neo-Orthodox-Realist Stream

Reinhold Niebuhr

- Richard Niebuhr

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Bernard Lonergan |

Transcendental Thomism |

| Avery Dulles |

|

- Broad-Church Anglican Stream

Keith Ward

Rowan Williams

John McIntyre

Henry Chadwick

Owen Chadwick

- Anglican ‘Orthodox’ Stream

Richard Swinburne

John Milbank

- British Religious Pluralist Stream

John Hick (United Reformed, Quaker)

Ninian Smart

John Hull

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Gavin D’Costa |

Studied under John Hick |

| Gerard Loughlin |

Mirroring God’s World: A Critique of John Hick’s Speculative Theology (1987) |

- Canadian-American Religious Pluralist Stream

Wilfred Cantwell Smith

Huston Smith

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Hans Küng |

Global Ethic |

| David Tracy |

|

- Anglo-American Existentialist Stream

Paul Tillich

John Macquarrie

- Anglo-America Process Stream

Paul Weiss

Charles Hartshorne

Robert Cummings Neville

John B. Cobb

- British Mainstream Neo-Evangelical Stream

John Stott

- American Mainstream (overlap in centrist’s Free and Reformed streams) Neo-Evangelical Stream

Carl F. H. Henry

Alvin Plantinga

Norman Geisler

Richard Mouw

William Lane Craig

J.P. Moreland

Geoffrey W. Bromiley

- A. Carson

- Scottish Calvinist-Reformed Stream

Donald Macpherson Baillie

William Barclay

- American ‘Neo-Liberal’/Universalist Stream

Langdon Gilkey

John Shelby Spong

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Hans Küng |

Rejection of Papal Infallibility; Global Ethic |

| John Courtney Murray |

Religious Liberty; Dignitatis Humanae |

- American Calvinist-Reformed Stream

Donald G. Bloesch

Gordon Clark

Nicholas Wolterstorff

- C. Sproul

- Anglo-American Radical Neo-Evangelical Stream

Ron Sider

John Howard Yoder

- Anglo-American Christian Ethics-Communitarian Stream

Stanley Hauerwas

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Alasdair MacIntyre |

Augustinian Thomism |

| G. E. M. Anscombe |

Analytical Thomism |

| Charles Taylor |

|

| Jean Vanier |

|

- British-South African (white)-American Pentecostal-Charismatic Stream

David du Plessis

Donald Gee

John Wimber

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| William Storey |

Duquesne University, Pittsburgh |

| Ralph Keifer |

Duquesne University, Pittsburgh |

| Leo Joseph Suenens |

International Catholic Charismatic Renewal Office |

| Pierre Goursat |

Emmanuel Community |

| Martine Lafitte-Catta, |

Emmanuel Community |

- British Conservative Evangelical (‘fundamentalist’) Stream

- I. Packer

- American Neo-Calvinist (‘dominance’) Stream

Cornelius Van Til

Gary North

- J. Rushdoony

Francis Schaeffer

- American Conservative Evangelical (‘fundamentalist’) Stream

Carl McIntire

John Murray

- Latin-Palestinian-American-African-German Liberation Stream (mainly Catholic in origins) Steam

Martin Luther King Jr.

Naim Ateek

Miguel A. De La Torre

Rubin Phillip

Robert McAfee Brown

George V. Pixley

Dorothee Sölle

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Hélder Câmara |

|

| Gustavo Gutiérrez |

|

- Sub-Continent ‘Indian’ Influence of Christo-Hindu (Gandhi) and Western Counter-Culture (Christian Anarchism) Stream

Mahatma Gandhi

Dave Andrews

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Bede Griffiths |

Benedictine |

| Dorothy Day |

Catholic Worker Movement |

| Peter Maurin |

Catholic Worker Movement |

- Indigenous Influence of Anthropological / Anti-Anthropological Stream

David Unaipon (Aboriginal Australian)

Douglas Nicholls (Aboriginal Australian)

John Harris (Aboriginal Australian)

Whakahuihui Vercoe (Māori church)

- Scott Momaday (Native American Church)

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| René Girard |

Fundamental Anthropology |

| Samuel Ruiz |

indigenous populations of Chiapas. |

- East ‘Asian’ Influence of Confucian-Buddhist-Tao-Shinto Stream

Watchman Nee

- S. Song

Simon Chan (AOG)

Kwok Pui-lan (Asian feminist theology)

Chung Hyun Kyung (Asian feminist theology)

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Thomas Merton |

Trappist |

| Bernadette Roberts |

Carmelite |

| Aloysius Pieris |

Sri Lankan Jesuit |

- Anglo-American African Black Revolutionary- Africana Stream

Cornel West

James H. Cone

Albert Cleage

Barney Pityana

Allan Boesak

Zephania Kameeta

- Anglo-American Quietism-New Thought-Unitarian-Universalist (Christian) Stream

Parker Palmer (Quaker)

- Elton Trueblood (Quaker)

Rufus Jones (Quaker)

Richard Foster (Quaker)

Emil Fuchs (Quaker)

Ernest Holmes (Christian New Thought)

Johnnie Colemon (Christian New Thought)

James Luther Adams (Unitarian-Universalist)

Webster Kitchell (Unitarian-Universalist)

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Henri Nouwen |

Catholic Quietism |

| Jean-Luc Marion |

Postmodern Phenomenology |

- Anglo-American Feminist Stream

Marcella Althaus-Reid

Phyllis Trible

| Catholic ‘Theologian’ |

Tradition |

| Mary Daly |

|

- Anglo-American ‘Death of God’-Secular Theology Stream

Harvey Cox

Don Cupitt

Paul van Buren

- Anglo-American Atheist-Deist Stream

Antony Flew

Brand Blanshard

The General Theory School

The modern general theory of religion begins in Otto’s universalisation of the ‘Holy’ – the belief that all world religions express and interpret the same Christian ‘Holy God’/ holiness, achieved differently through distinctively shaped cultural filters. From this schema comes the task of religionists to develop models to explain diverse religious beliefs and practices. A central theme is an assumed division between ‘insiders’ and outsiders’ (McCutcheon). The premise is that only those acquainted with the inner life of a particular set of religious belief, experience, or practice are able to articulate that particular model of religion. It is a contentious point on a number of levels. Globally, it suggests that the historical category of religion in western thought is not applicable to non-western cultures, as argued by McCutcheon. Rather than seeing ‘foreign’ cultural practices as simply ‘insider and outside’, both Fitzgerald and McCutcheon created a more articulated political binary of the colonialized and colonizers. Locally, there is fragmentation in the possibility of reducing an organisational inside to one person. Furthermore, the insider-outsider binary is existentially suspect, given the fluid nature of being inside and outside over the course of a person’s life.

The General Theory School begins as a universal understanding of the Christian faith from those who were largely European religionists who shared Christian thought in a slow pluralistic turn. Jesus Christ was said to have died and redeemed the whole of humanity, and each ‘religion’ is a pathway of salvation which leads to ‘God’ as conceived by Christians. The General Theory provided a pluralist perception of a Christian exclusive belief. Placed on a spectrum of belief, from rigid (hard) confessionalism to a vague (soft) universalism, the General Theory allowed religionists and educators to combine a thorough understanding of ‘faith’ across cultures and personal soft confessionalism. The challenge to the General Theory is in the possibility for education. Knowledge of religion, in the General Theory, inferred an ‘essence’. However, the essence was assumed to be informed by Christian beliefs which cannot be known in other cultural contexts.

The Phenomenological School

The General Theory had to be modified in the very least. The Phenomenologists, and later Existentialists, rejected the over-theorising from logicism or rationalism. Whereas those who worked in general theory tended to place primary on reason and logical connections, the Phenomenological School emphasised the ‘pure’ experience. They were influenced by Absolute Idealism of F. H. Bradley (1846 – 1924) and Josiah Royce (1855 – 1916). The Phenomenologists took the original ideas of G.W.F. Hegel (1770 – 1831) which was the groundwork for the modern concept of Spirit (or Absolute). However, they stripped off the metaphysics and replaced it with James’ radical empiricism – an assumed sufficiency of the subject’s observation of its subjectivity. The idea of ‘being’ became ‘essential’ (pun) in the development of the school. What was an epistemological enterprise in the General Theory School now became studies in ontology.

Heidegger is an important historical figure for the contemporary ontological debates, centring on the arguments of his Being and Time (1927). His approach was known as Existential phenomenology, which distinguishes Heidegger’s philosophy from the established modern phenomenology of Husserl. Husserl’s approach is known as phenomenological reduction, an act of suspending judgment about the natural world to instead focus on analysis of experience. Husserl is singularly concerned about intentionality, what is no more than a person’s claim for intentionality and how mental representation occurs. All of these ideas and concepts feed into the academic study of ‘religion’. Furthermore, Henri Bergson (1859 – 1941), with his ideas of processes of immediate experience and intuition (coming together in a universal Élan vital, the process of creative evolution) was also very significant; significant in a great part because it bridged with the General Theory and the process philosophy of Alfred North Whitehead (1861 – 1947) where mathematics, logic, and physics played an important role for both Whitehead and Bergson. Within the Phenomenological School, then, there became a tension between the traditional method of Husserl, where education bracketed away any truth matters, and the inescapable universal theorisation which had to be epistemological justified. Eliade’s great use of mythology in what was called ‘History of Religion’ field (more abstract anthropology than what can be called ‘history’) abandoned any argument for the subject’s valid belief. Paul Tillich’s idea of ‘ultimate concern’, following Heidegger’s idea of Dasein (being there, presence, human being) provided a general theory to phenomenology. Ultimately, there was a universal truth in religion, according to Tillich’s liberal religion.

The Cultural Pluralist School

The World Religion movement could be the other identity of the Cultural Pluralist School. The concept of cultural pluralism as religion has its development in the larger movement. Although the concept of world religion goes back to the nineteenth century, with the clearest organisation in the Parliament of the World’s Religions (1893, 2018), the educational development is recent. Ninian Smart (1927 – 2001), with other scholars, formed the Shap Working Party on World Religions in Education in 1969. There was a concerned that the phenomenology of religion had taken over the field and had placed an emphasis on description rather than critical analysis. The alternative was to see ‘theology’ as being central to a given ‘religion’, and the emphasis for belief reflected the socio-political agendas of 1960s Britain. Smart was very much the driving force. In 1967 he established the first department of religious studies in the United Kingdom at the new University of Lancaster. Smart had come to the enterprise from the department of theology at the University of Birmingham. The enterprise was a better, more philosophical, formation to what had been, in the theology discipline, comparative studies in ‘religion’. Smart was the first J.F. Rowny Professor in the Comparative Study of Religions at University of California, Santa Barbara. Smart’s textbook, The World’s Religions (1989), achieved this by giving the category a sevenfold scheme of study:

- Doctrinal

- Mythological

- Ethical

- Ritual

- Experiential

- Institutional

- Material

It was helpful for the field, but it became apparent that the schema defined the perspective which could be taken but it still did not touch the problem of the categorisation. The approach took liberal Western Protestantism as its baseline and interpreted these different ‘religious’ traditions through the framework of liberal Protestant norms and values. As a result, the utility of the World Religions Paradigm had experienced a sustained and rigorous critique from many scholars of religion. In 1978 Jonathan Z. Smith called it a ‘dubious category’. Two other criticisms followed. The paradigm is rooted in the discourses of modernity, including the disproportionate power relations present in modern society. The paradigm is ultimately an uncritical and sui generis model of ‘religion’.