The purpose of this article is to demonstrate the broad-humanist outlook which exists across multiple worldviews of actual thinking persons, by way of a summary of the Pew Research Center’s report, entitled “What Makes Life Meaningful? Views From 17 Advanced Economies.” The report is produced by Laura Silver, Patrick van Kessel, Christine Huang, Laura Clancy and Sneha Gubbala, published on 18 November 2021. The summary of this particular Pew report, to make the main point on broad-humanism, is significant. According to secular humanists or secularists, the Pew organisation is religiously-bias towards religion against ‘humanism’ or, at least, places ‘religion’ well-above humanist evaluation. Whether the charge is true of the Pew organisation or not, the charge cannot be made against this particular report, one that demonstrates the strength of broad-humanist values among the global population, but with less strength for religion among those who inhabit particular national cultures. The case of the United States of America being the exception, and being the predominant case of anti-humanist attitudes – hateful and nasty misanthropy. It is not that misanthropy does not appear strongly in other cultures, but it is that, during the 20th century, a dominant cultural and history narrative arose in the United States: the argument that ‘true religion’ and ‘true secularity’ were incompatible with each other, and cultural warfare was greatly promoted. Those intellectuals and educated populations from other global-transmissible cultures find Americans in this argument completely absurd, and totally ignorant to many better worldviews, and the ways of the world.

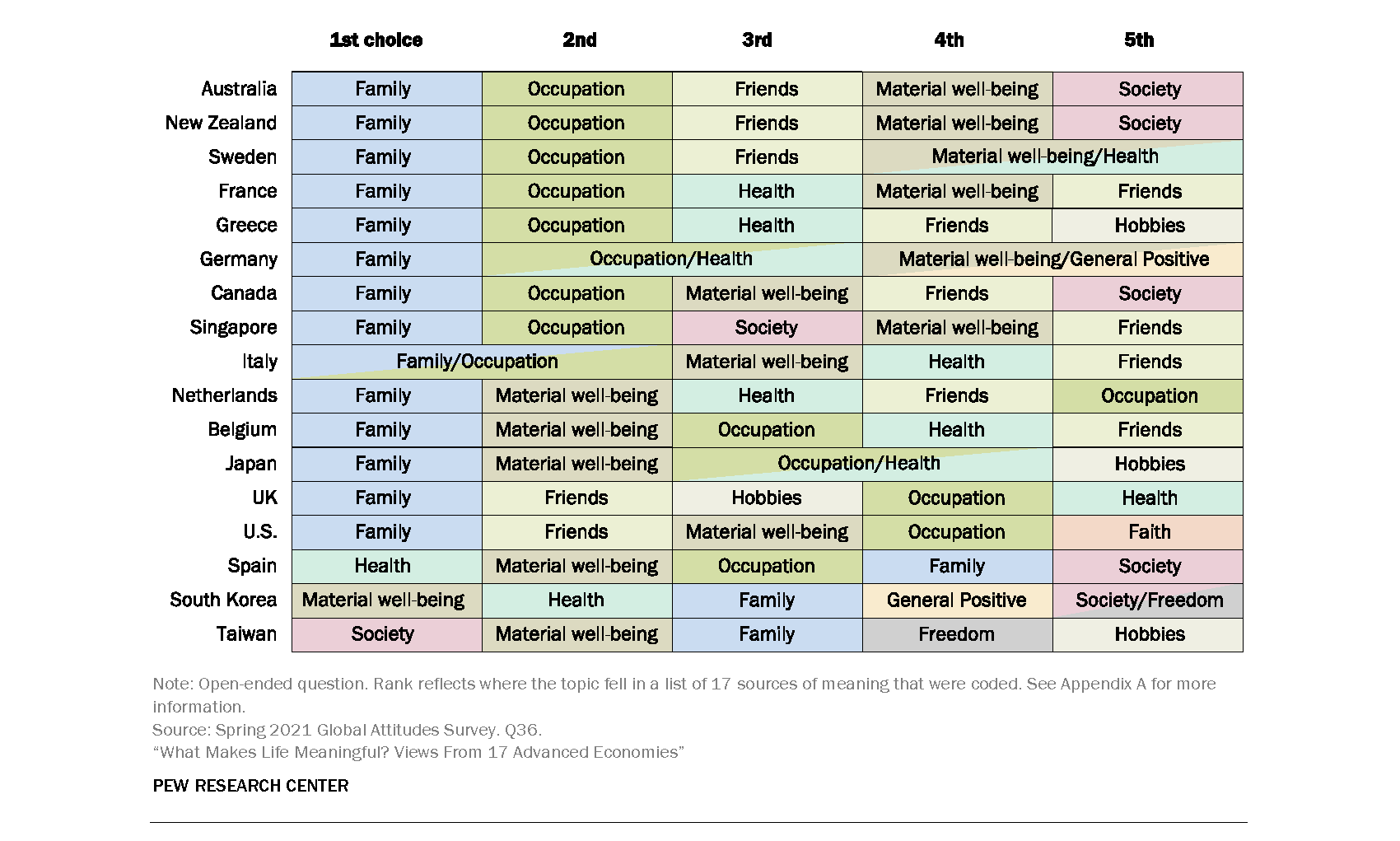

This Pew report contradicts the warfare view of dogmatic religionists and secular humanists/blockheaded secularists. For an organisation which is supposed to be promoting religion, the report demonstrates the opposite of the polemics. What makes life meaningful in the views of 17 advanced economies is family, with work, material well-being and health also play a key role. Religion is comparable down the list of evaluation, and even ‘spirituality’ is low. Nevertheless, religion and spirituality are listed and its evaluation still ranks broadly.

My argument is that the full list of values ranked are what makes the characterisation of broad-humanism. No matter the personal priorities, contra the argument of cultural warriors, the broad population are human, not inhuman, fostering the values of what it is to be human.

Nevertheless, each is behold to a cultural bubble which shaped the personal identity and the outlook of each and upon each other. I am an Australian. So, this drawing out the global humanist characteristics must come from an Australian perspective, which also explains why I have adopted a critical thinking view of Americans; NOTE, not an anti-American view but a view which is critical because he sees much worth in the American culture, enough for it to be criticised. I love several American persons I know personally, and I do not begrudge their cultural outlook. My criticism is only upon a way of thinking which needs modification or radical reform, not to be overthrown or dismissed out of hand.

The Pew Research Report Conclusion

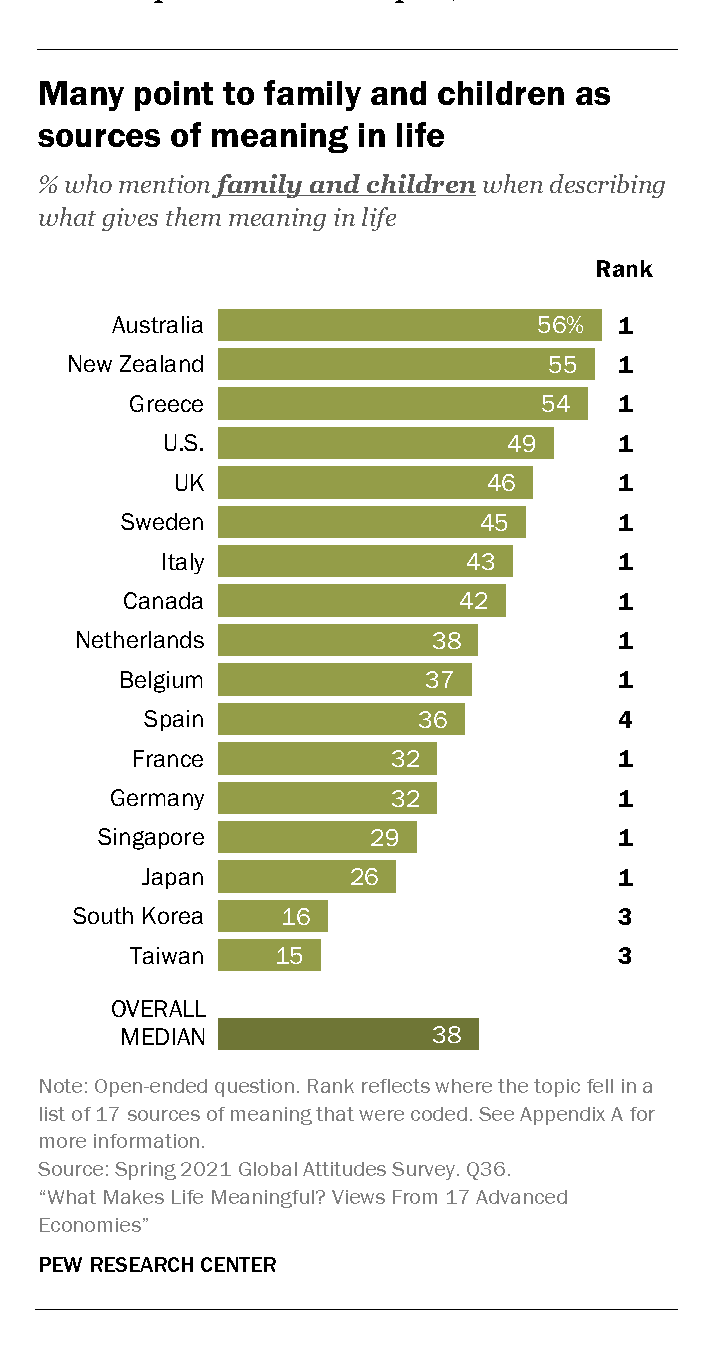

There are two major conclusions from the report. Family is a global value, but it is not the only valuing.

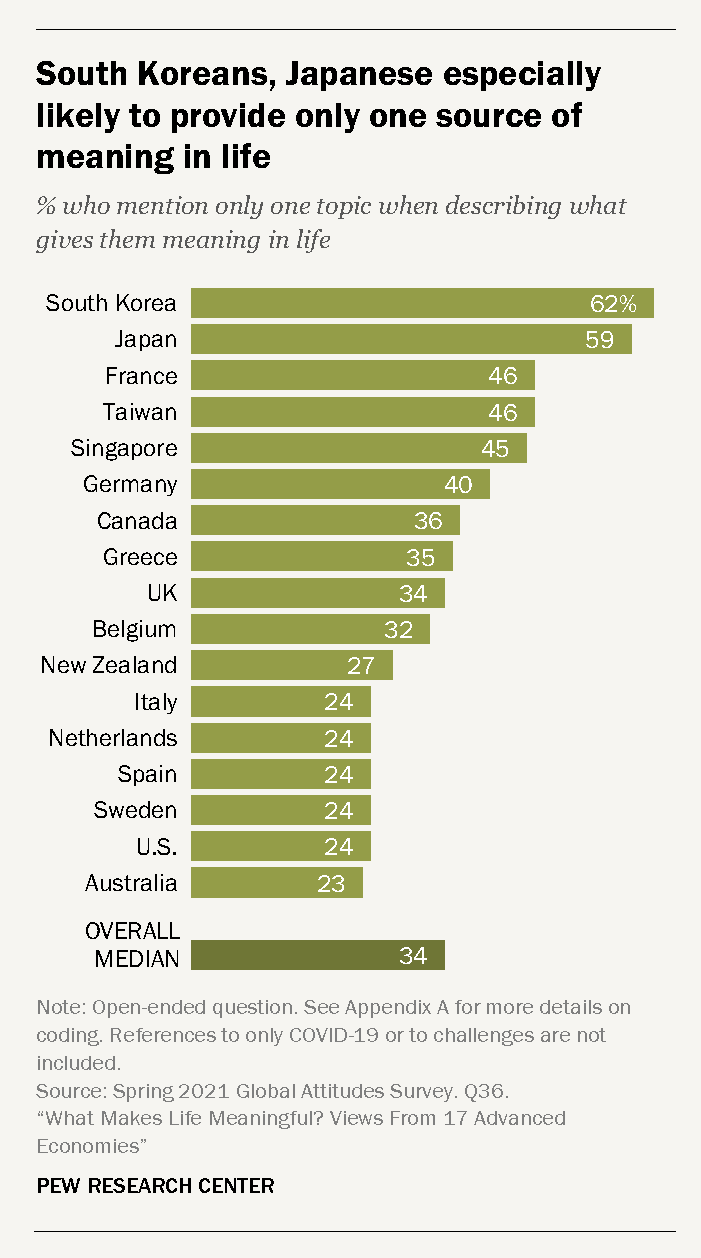

And there are some places where the population are more likely to reduce the meaning in life to one value. And there are other places where the population can deal with the diversity of value better. Nevertheless, there are large sections of the population (23% and over; 34% overall median) who keep reducing human valuing to one ideological statement. They are the ones with the problem, given that knowledge never works in such a naked reduction.

For better understanding I am reinterpreting a few of the measurements by philosophic terms.

Where Australian Culture Ranked Higher in Humanist Evaluation

First

Where Australia ranked first among the 17 countries was in the human valuations of family, friends, and community, and education and learning being significantly ranked and proportioned in the population. A few stereotypical values then follow.

At 56% of Australians described the meaning in life as family.

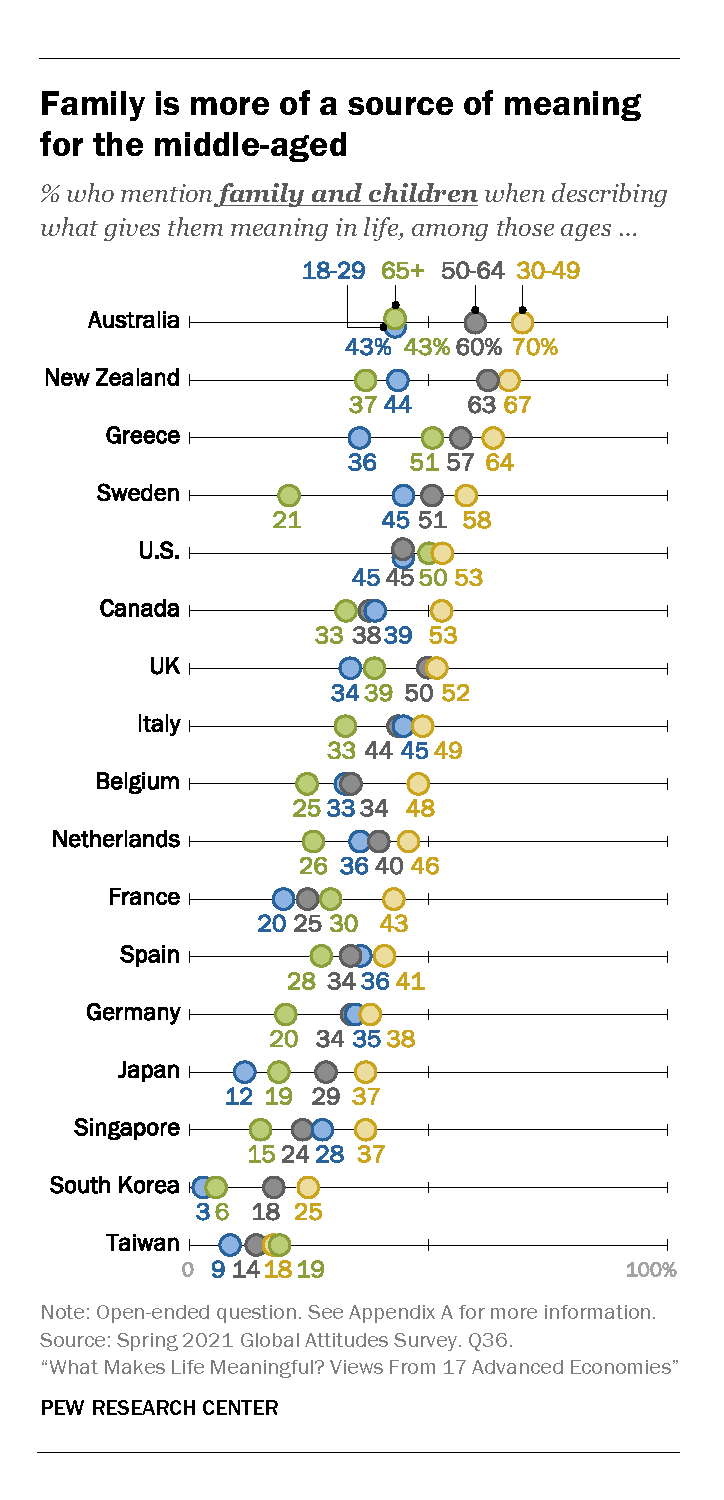

The difference between the age groups in Australia was the highest in the evaluation of family as the meaning of life. The 30-49 age group achieved 70% against the much lower share from other countries.

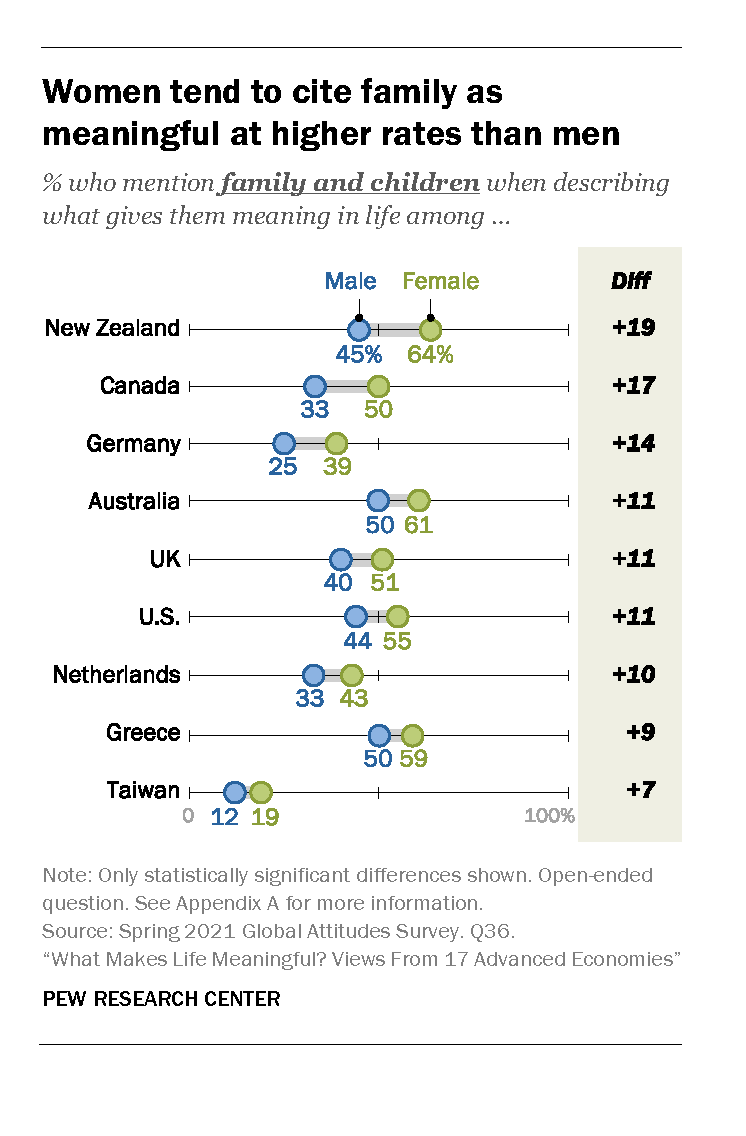

The difference between male and female respondents in Australia, speaking for family, was +11 but that gap was much less than the top three, New Zealand, Canada, and Germany.

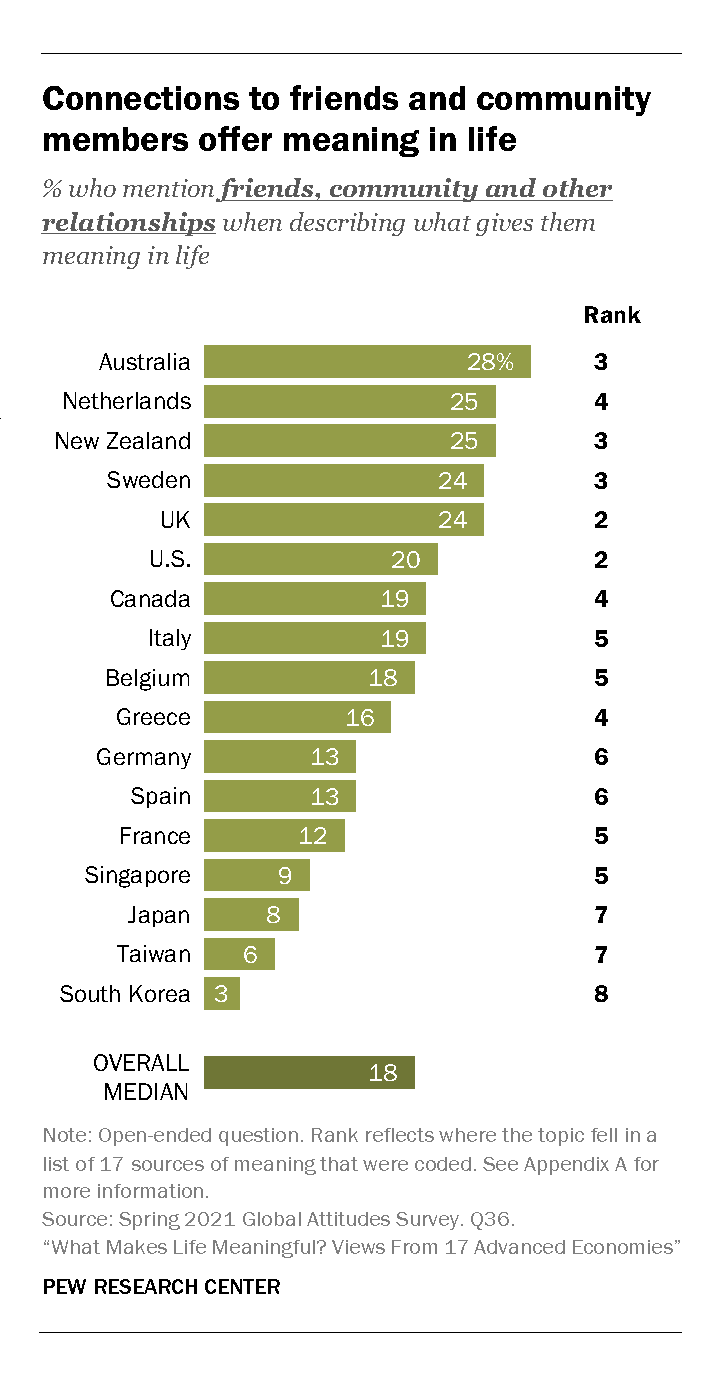

As ranked, 28% of Australians described the meaning in life as the relation among friends or in the community.

The strong sentiment, though, is among the younger Australians, 43% for the age group 18–29-year-old. Intuitively, that makes global sense of what most experienced at that stage of life. Leaving family and making new families. Young people also rate friendship and community highly, and there be a correlation with the responses to family and children.

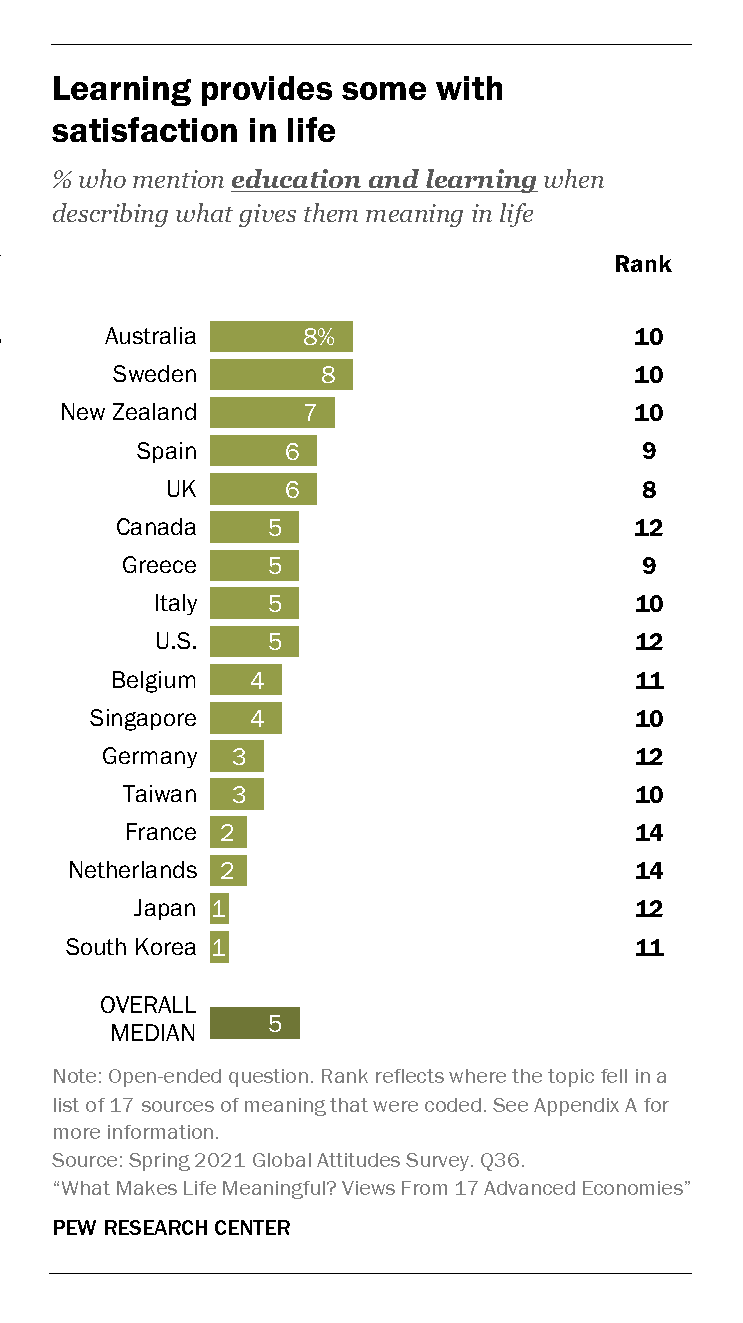

As ranked, 8% of Australians described the meaning in life as education and learning.

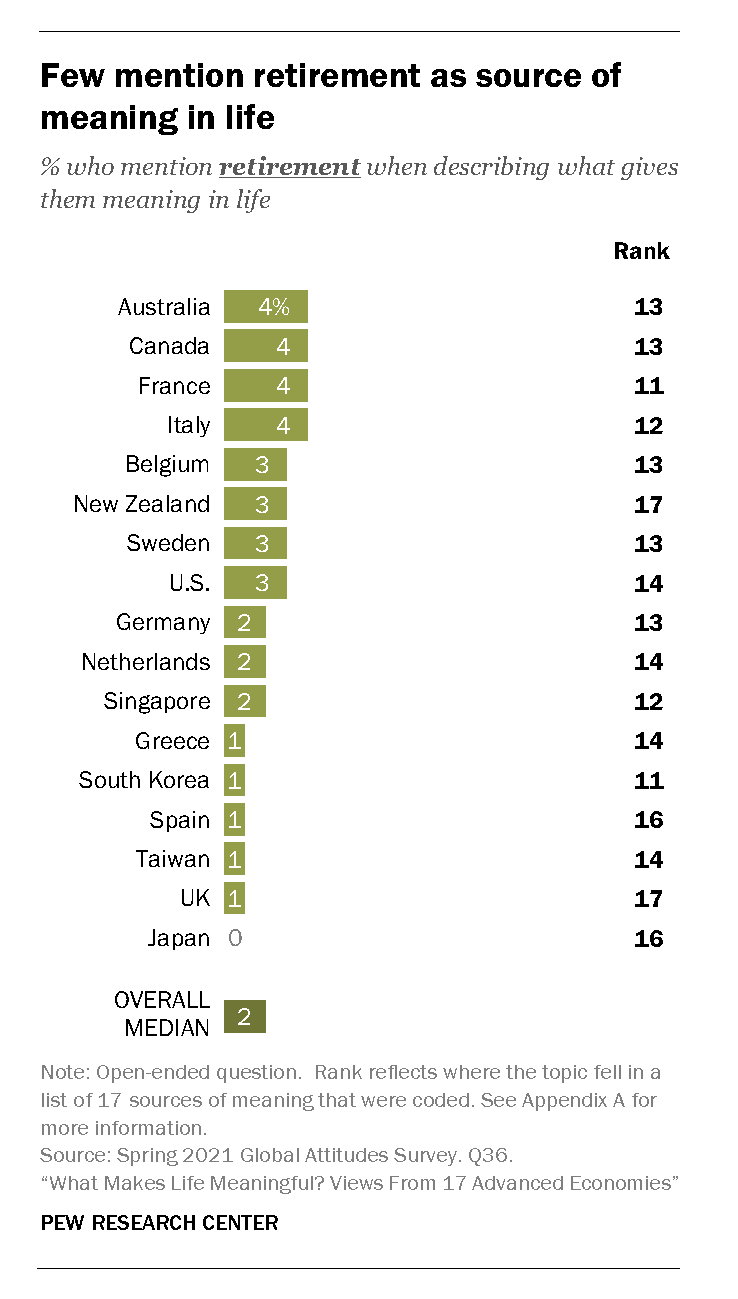

As ranked, 4% of Australians described their retirement (potential or actual) as the meaning in life. Four percent appears low, but as a section of the population anything in the range of 3-10% translates into sizable numbers, remembering that percentages are comparable. Minorities can rank in first position. In such case the numbers might speak to personal beliefs which do not match the larger portion of the population and where there are still dominant narratives which does not necessarily have to be statistically at the top to provide importance. Sociologists know that Australians have popular talk on work and retirement, where the dominant narrative is for less work and less career commitment. And the 4% suggests a possible correlation between retirement and the valuing of education.

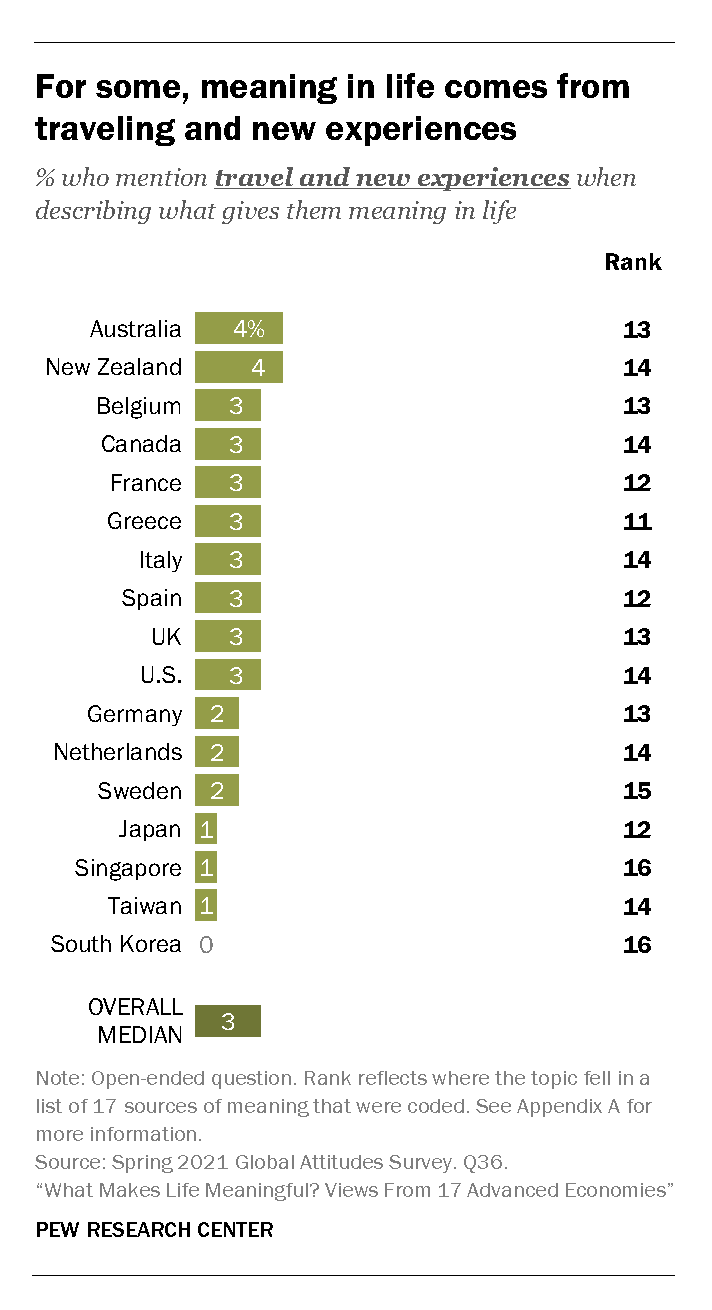

The same appears true as well with Australians (4%) who described their travel (potential or actual) as the meaning in life. Again, like retirement, travel is a stereotypical image of Australians.

Second

Where Australia ranked second among the 17 countries was in the human valuations of spirituality, nature, and civic engagement. And we do like our pets.

This is the second statistical tier. The percentage might be low but as a ranked comparison of 17 national populations, Australia comes out fairly well on top.

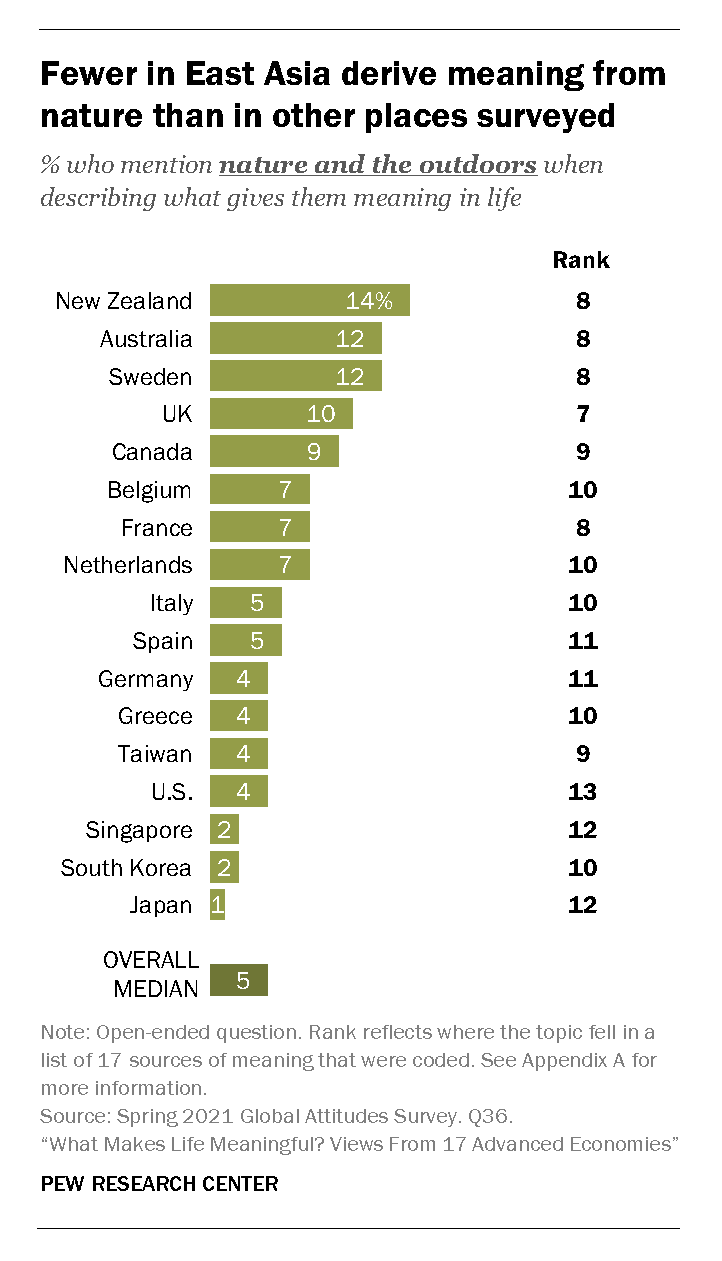

Rather than the anti-religion narrative one hears on social media and the ‘twit’ world of persons, what we are seeing in Australia (14%) is a reprioritising of nature and the outdoor valuing over formal religion, and that Nature narratives includes both valuations and motifs of spirit and material. Nature (14%), whatever it be, has certainly outweigh the narratives of formal religion (4%).

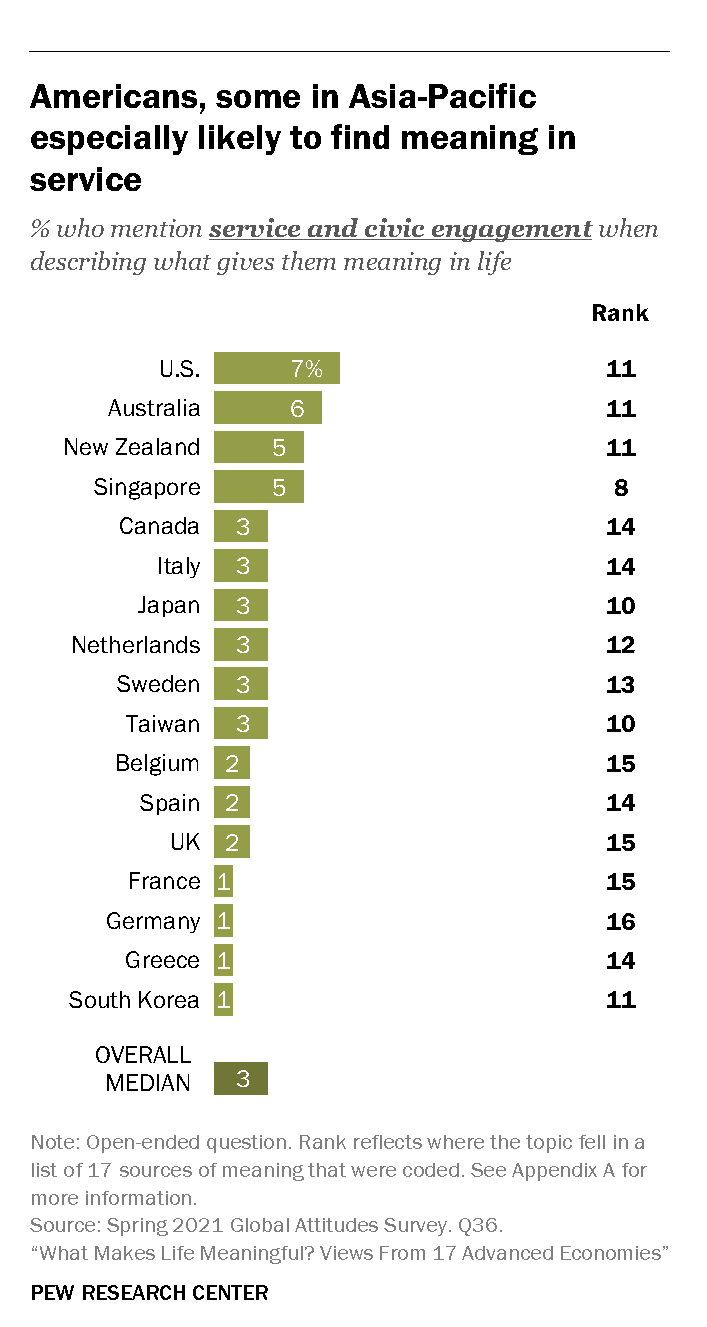

Like the United States, there are large numbers of those who do carry the weight of the nation’s service and civic engagement, but that number is a very small minority of those who find meaning in life from such work (6-7% of the population).

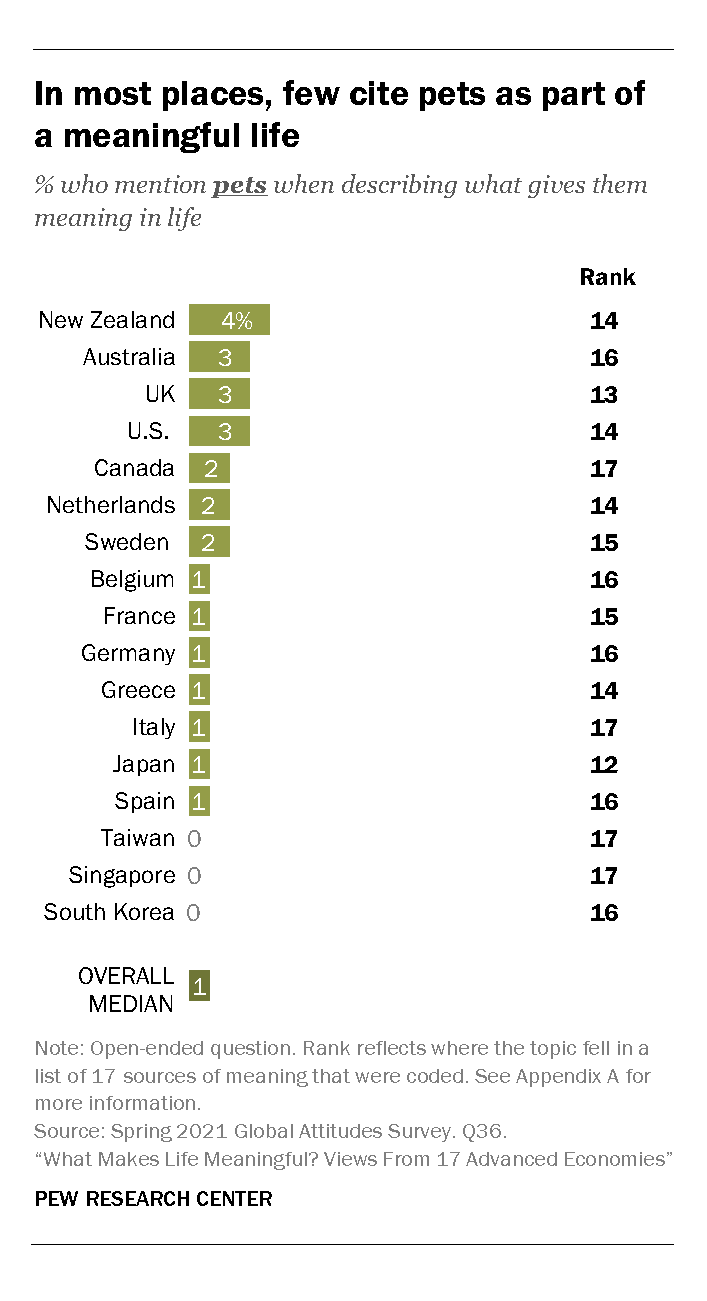

Perhaps, pet-owning expresses the comparison nature of a minority of Australians, significant when ranked. There is an argument that pet-owning is kinder than over-populating the earth with human children. The meaning in life comes from pets when they are the substitution for child-bearing and child-rearing. Perhaps, if enough of the population choose this evaluation the rest can produce children for sustainable populations.

Third

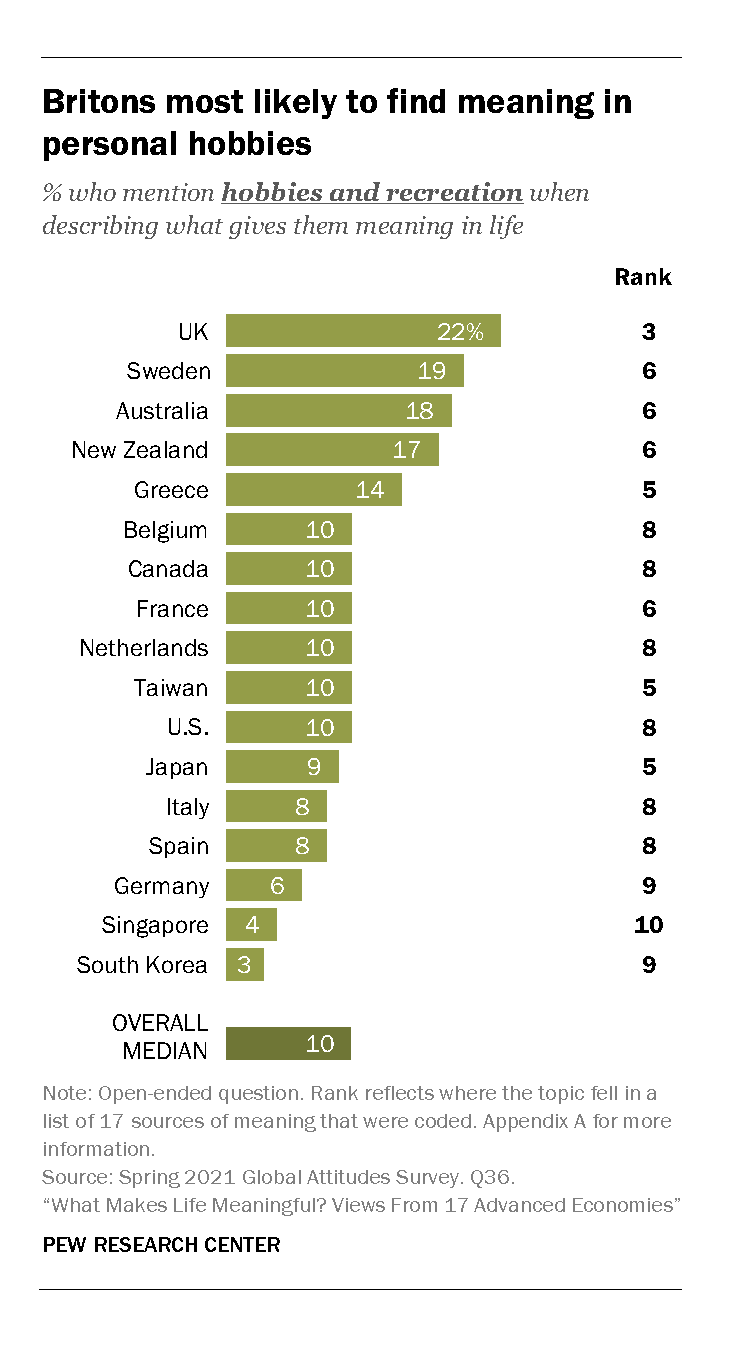

Where Australia ranked third among the 17 countries was in the human valuations of hobbies, with spirituality and faith taking an important place in Australia as far as a sizable section of the population.

The stereotypical description of Australians is of a practical people, so it is no surprise that Australia is ranked 18% of those who find the meaning of life in hobbies and recreation. Personal identity is shaped by the dominant national narratives, and if a people are told that they are practical they will be practical.

In Australian mythology religion is associated with unpractical abstraction, and the secular as practical.

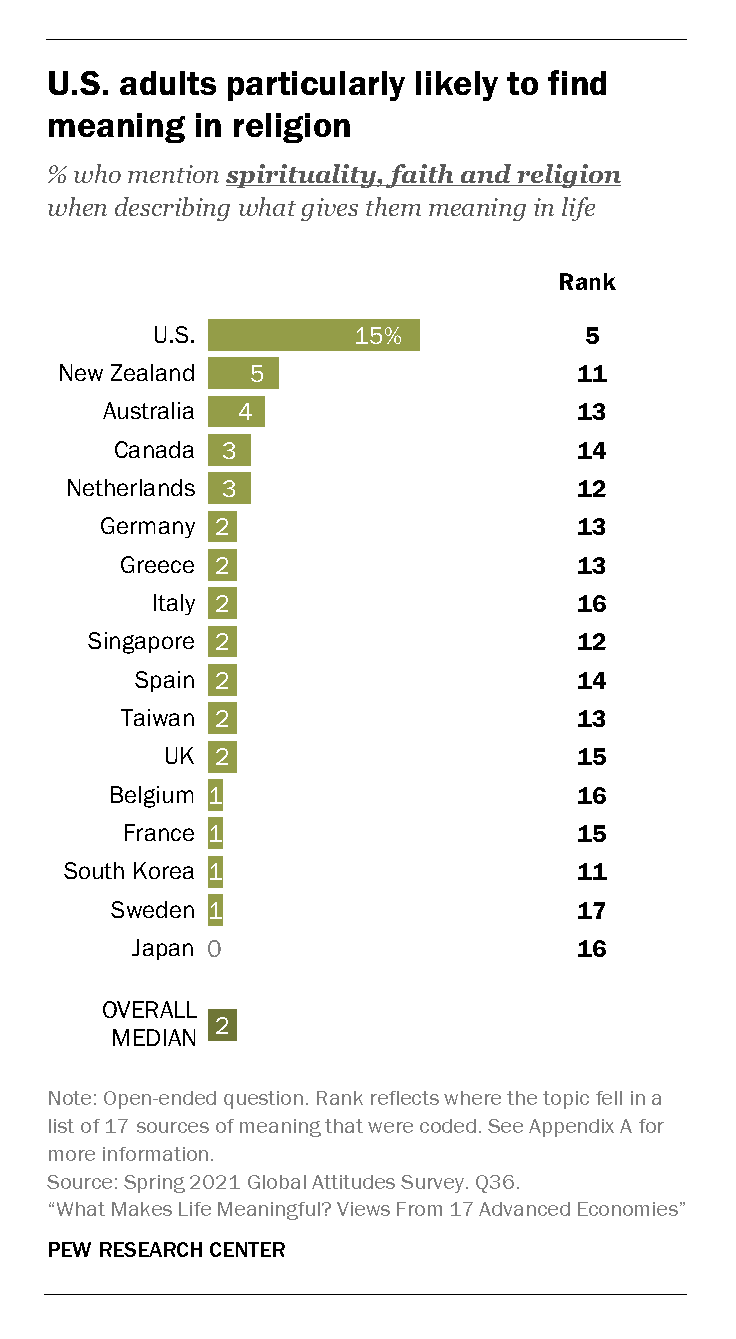

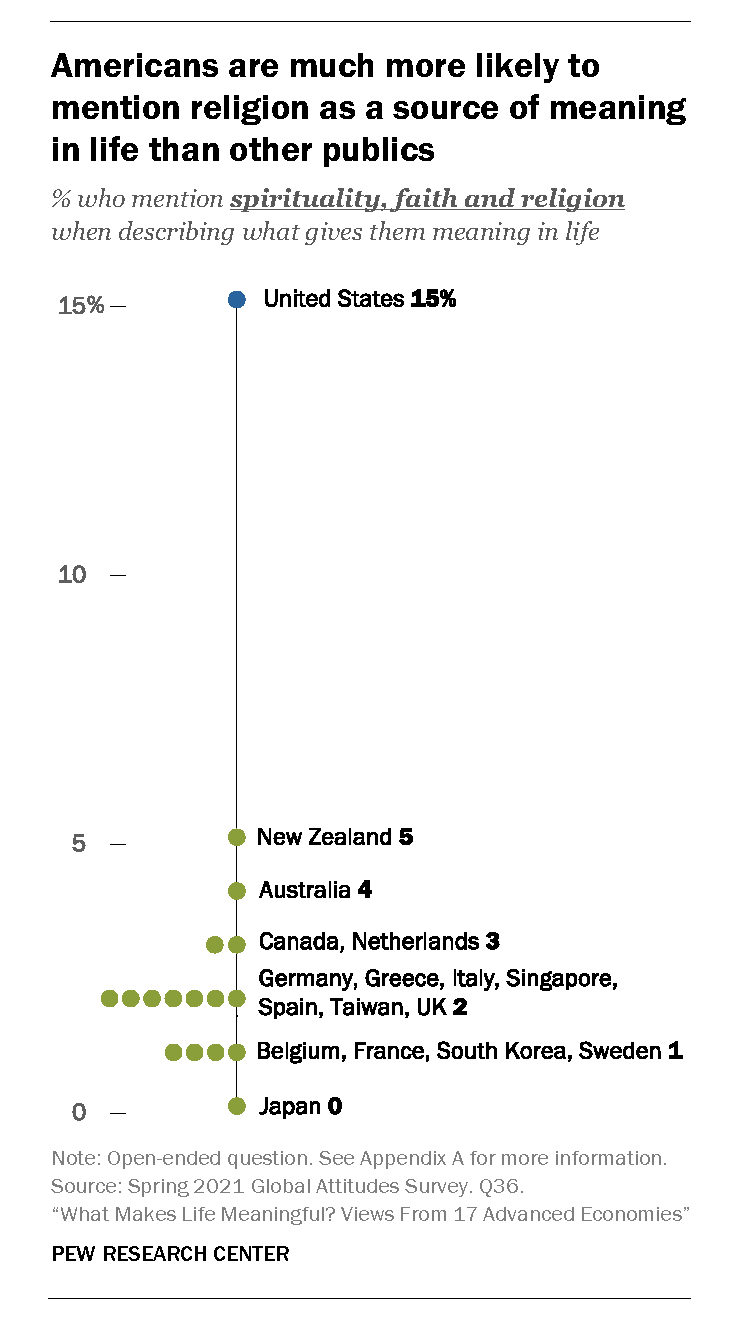

The secularist has argued that Australia is a secular country, but it is polemically designed to counter the other ridiculous argument that Australia is a Christian country. Sociologically, both arguments are, to be frank, stupid. They do sit at all well with the sociological studies of the last 30 years and are only the polemic fuel for the fires of the cultural-history war. Australia (4%) is well down on the ranking for spirituality, faith, and religion, and particularly compared to the United States (15%). Four percent of the Australian population is still significant in the social-political making (25,739,256 population by 4% = 1,029,571 persons).

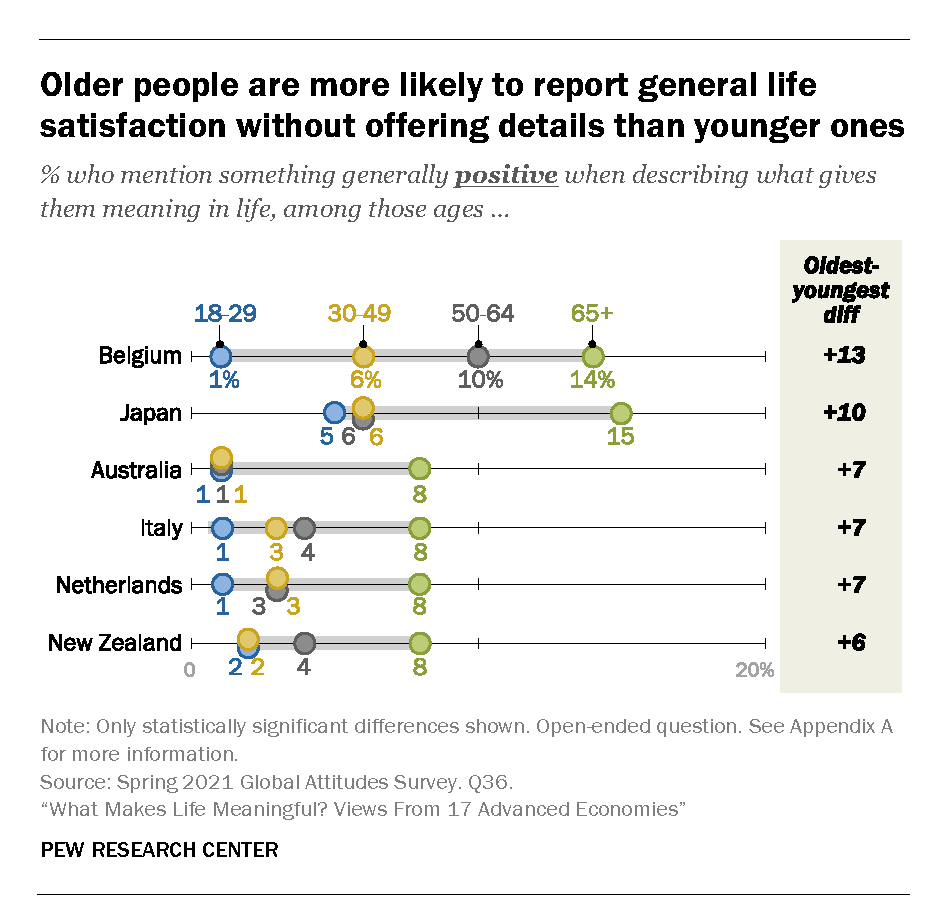

As will be mentioned further on, positivity in describing meaning in life is ranked low for Australia, but Australia has a more positive outlook with the same measurement according to the difference between the youngest and oldest in age. Both Younger and Older Australians are more positive, with a drastic reduction in positive thinking for the middle aged.

Where Australia ranked lower in the Pew rankings, taking only the first three positions was:

Very last

Where Australia ranked very last among the 17 countries was in reducing the human valuations to ‘the one’ (23%). It might be a weak signal that Australians are diverse thinkers.

Second Last

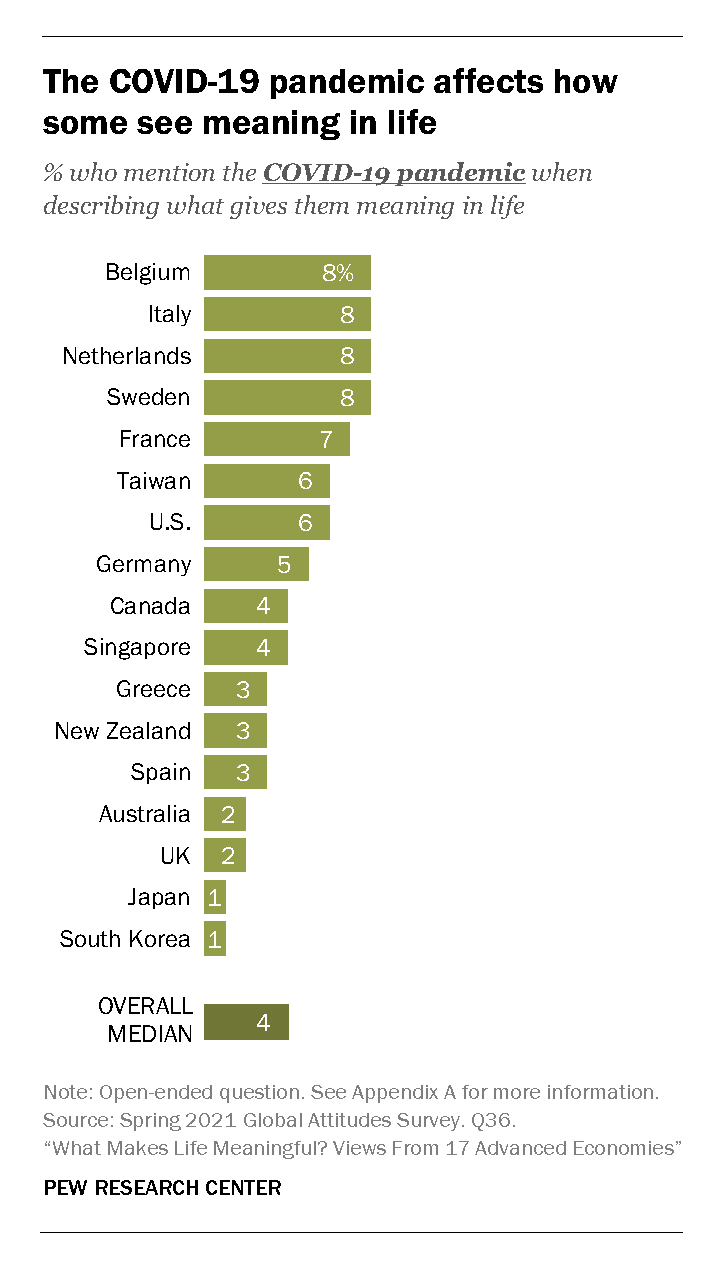

Where Australia ranked second last among the 17 countries was in the human valuations of whether the Covid-19 pandemic gave meaning of life. It was an open-ended question, and such a question is ambiguous. It would not be reasonable to place too much on Australia’s ranked position (2%).

Third Last

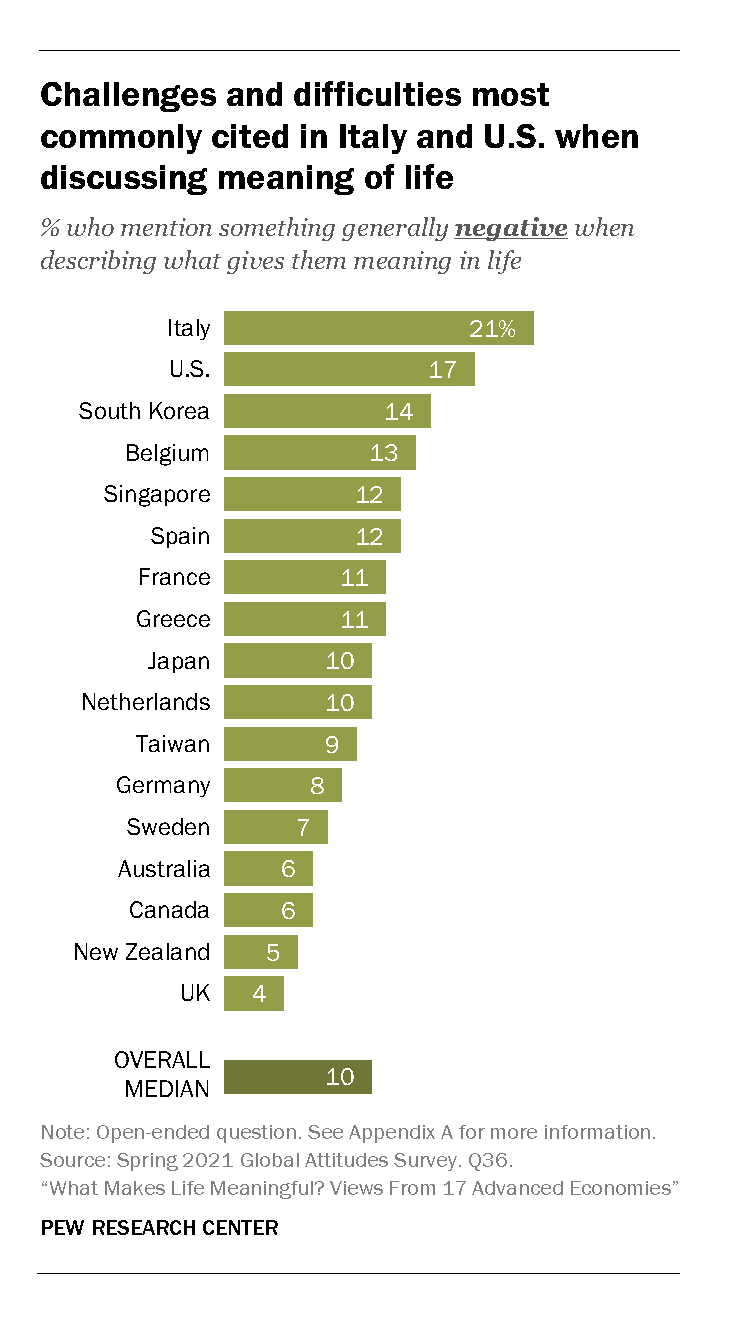

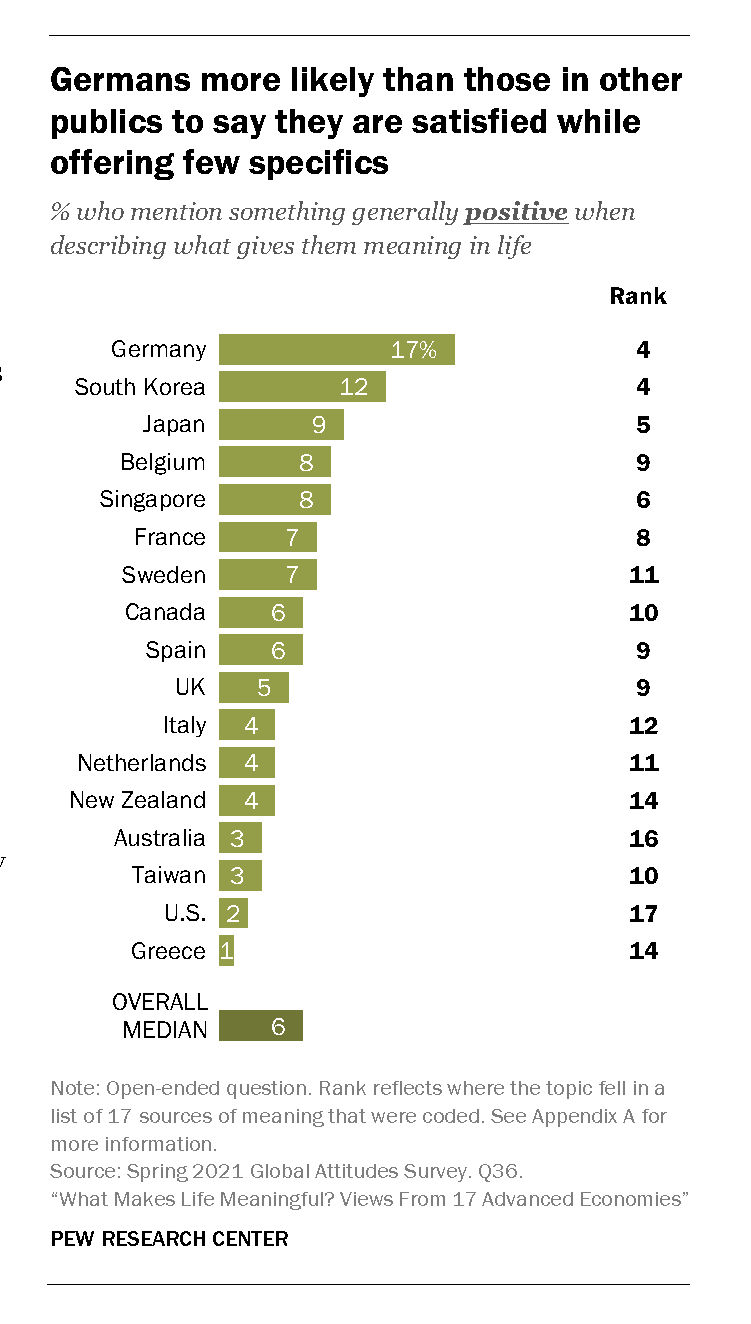

Where Australia ranked third last among the 17 countries was, oddly enough, in the human valuations of negativity (6%) and positivity (3%) for the meaning in life. What does that say? Perhaps, Australia is neither a particularly negative nor positive country.

Other Humanist Valuation

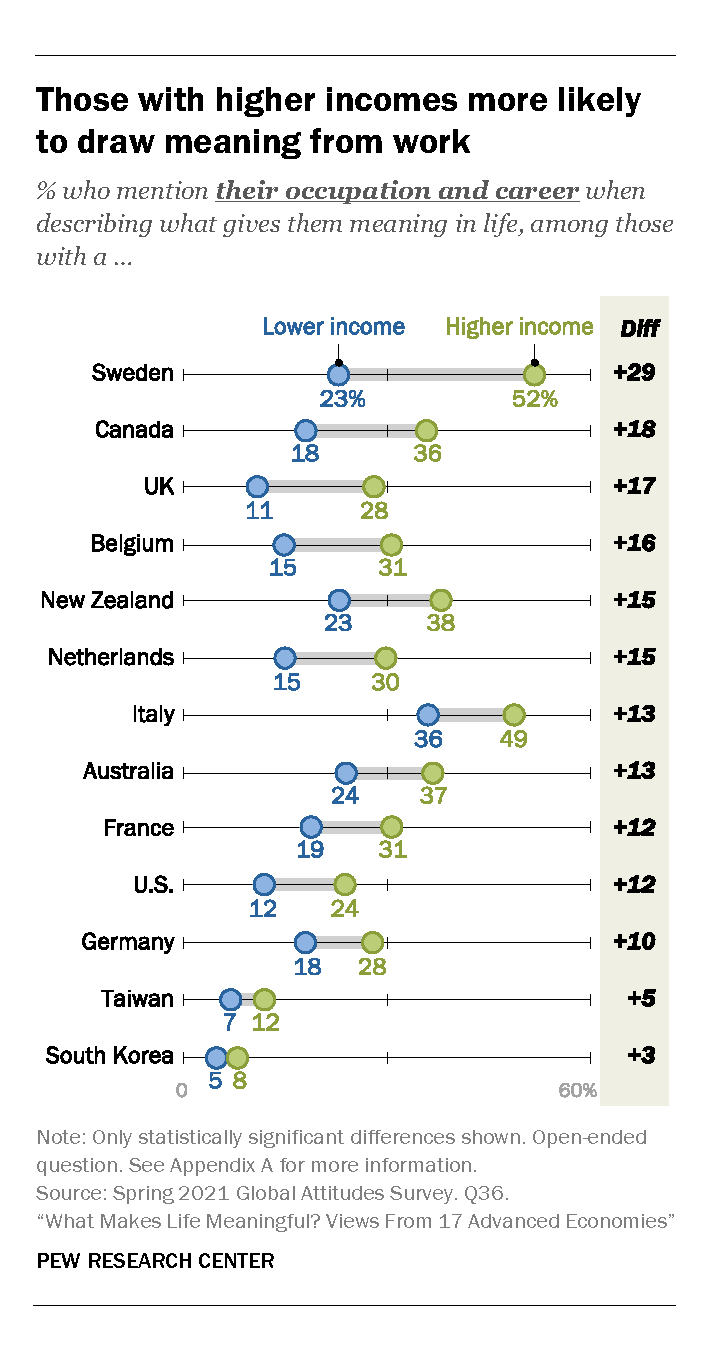

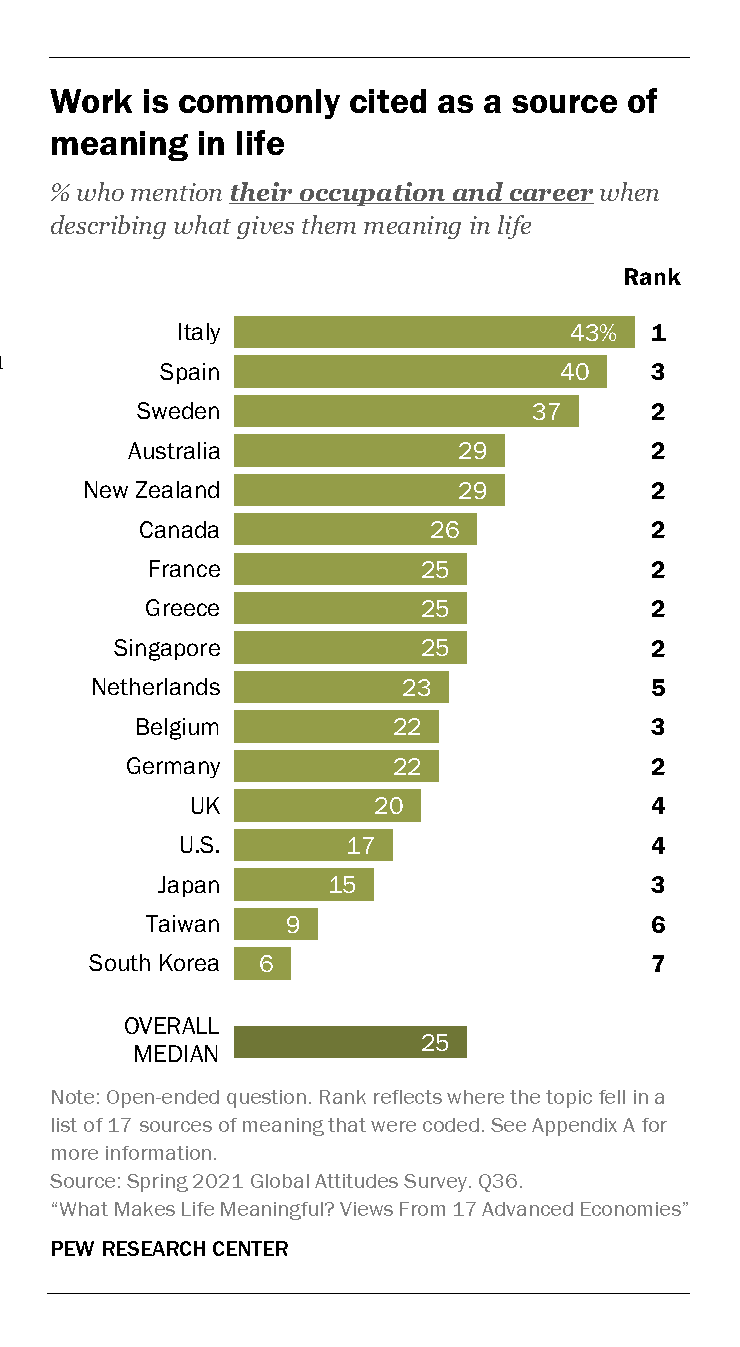

The feeling on occupation and career among Australians is neither high nor low comparably. Those with higher incomes (37%) would obviously value occupation and careers higher.

Australians value work (as occupation and career, 29%) but not as high as the top ranked in Sweden (37%), Spain (40%), and Italy (43%).

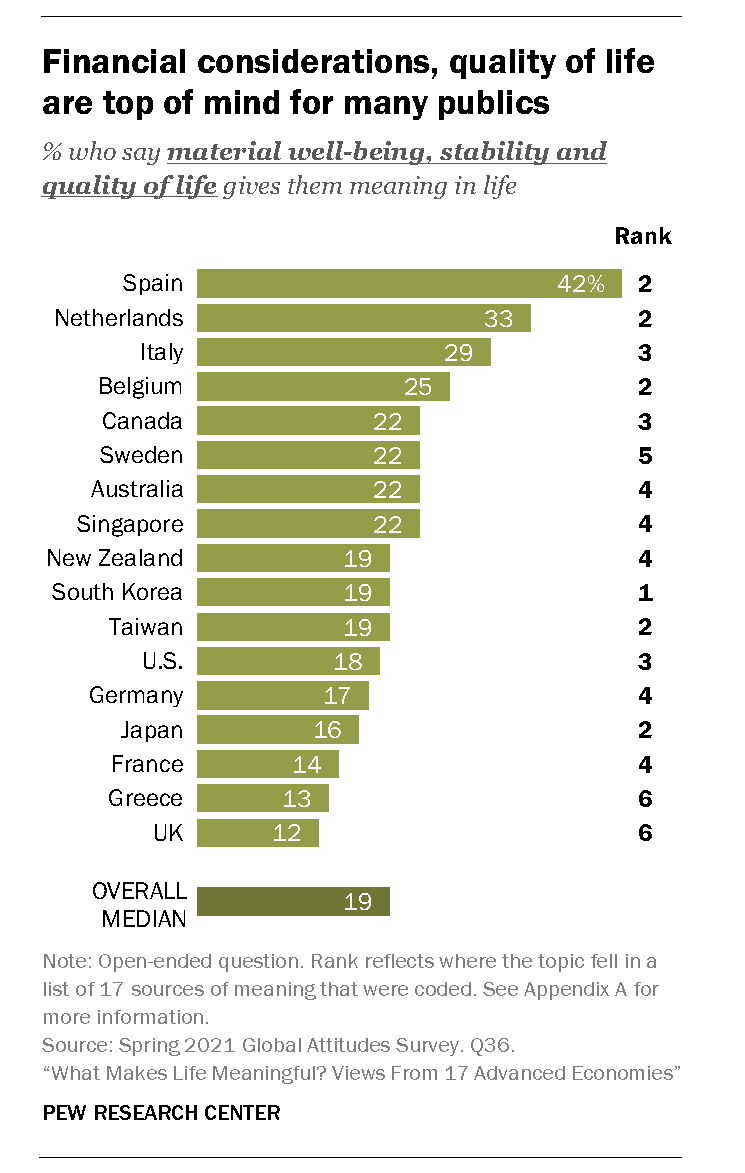

In this regard, as opposed to the national stereotyping, Australia is not particularly materialistic than other places, if we consider the meaning in life from material well-being, stability, and quality of life (22%).

In the silly materialistic against spirituality arguments (and visa versa), there is not much evidence that Australians are interested in the stupid cultural-history wars on such terms.

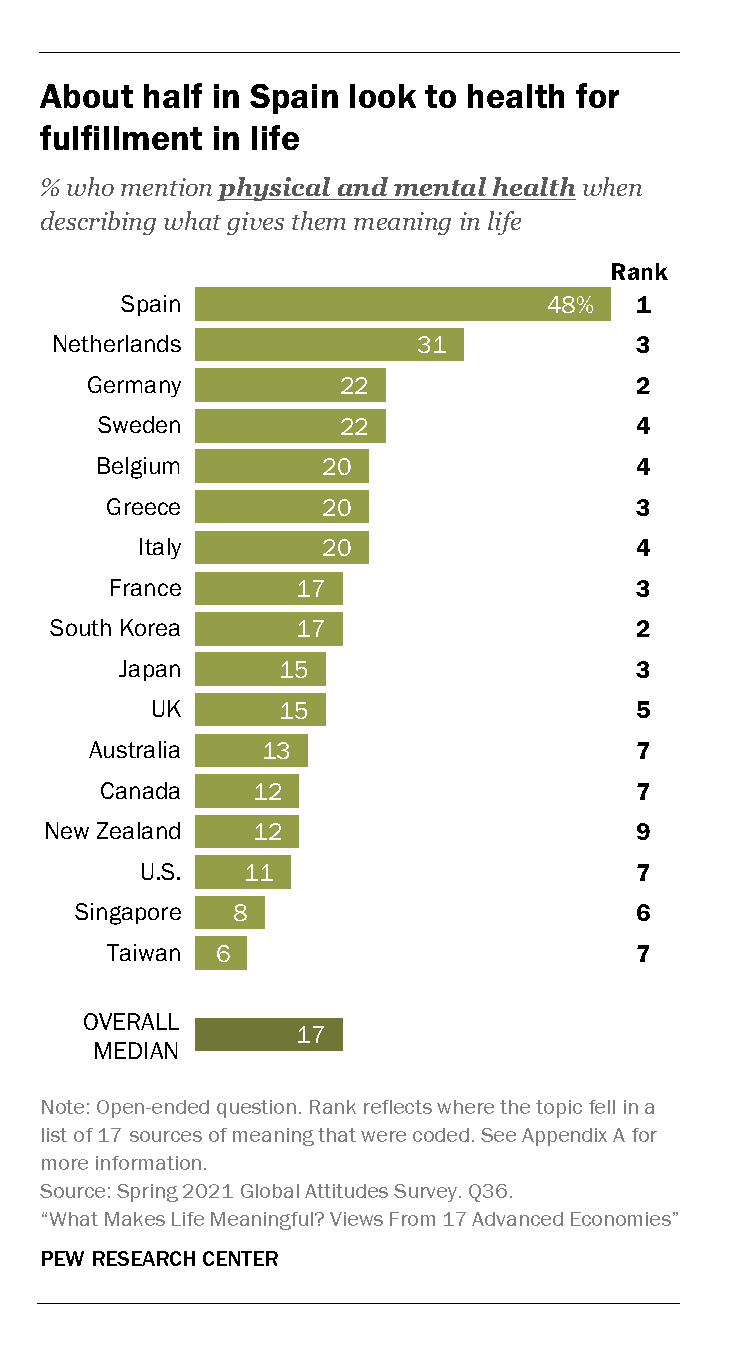

Australia is not particularly high in either rating physical or mental health (13%).

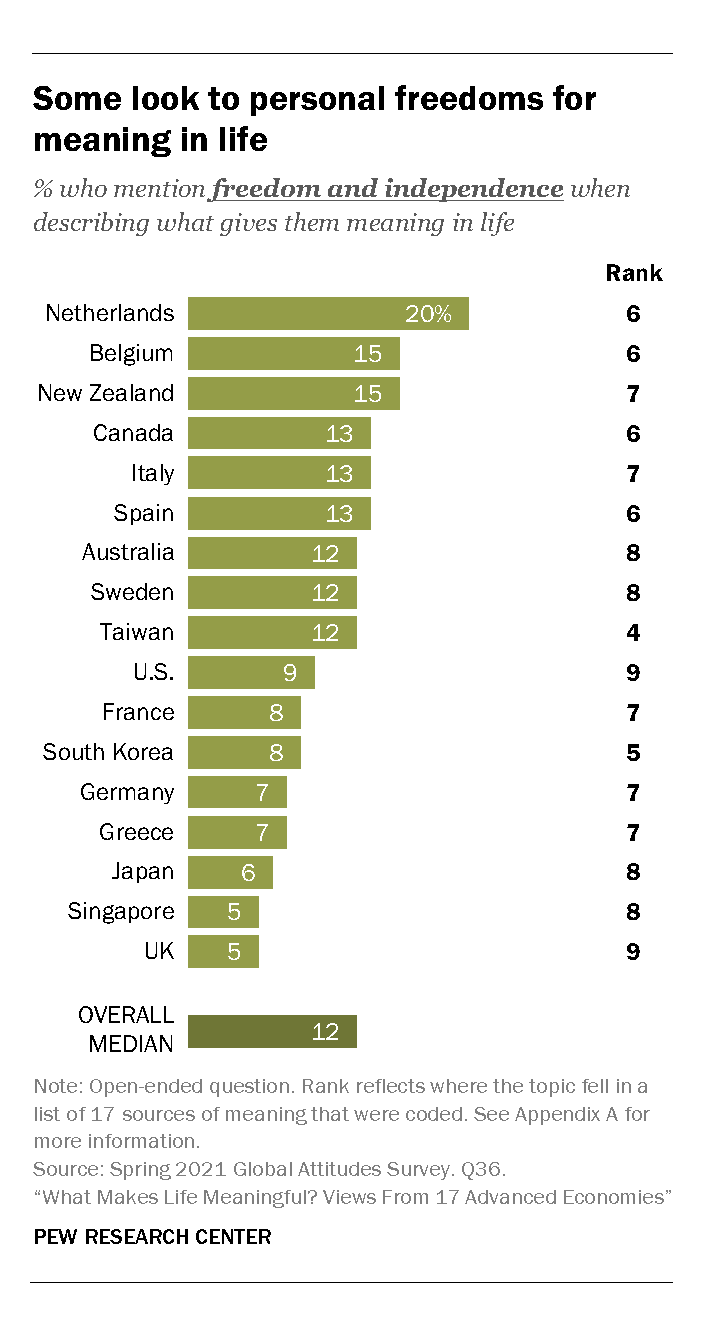

It is not that a sense of determinism or fate is driving matters for Australians who come fairly middling in seeing freedom and independence as meaning in life (12%).

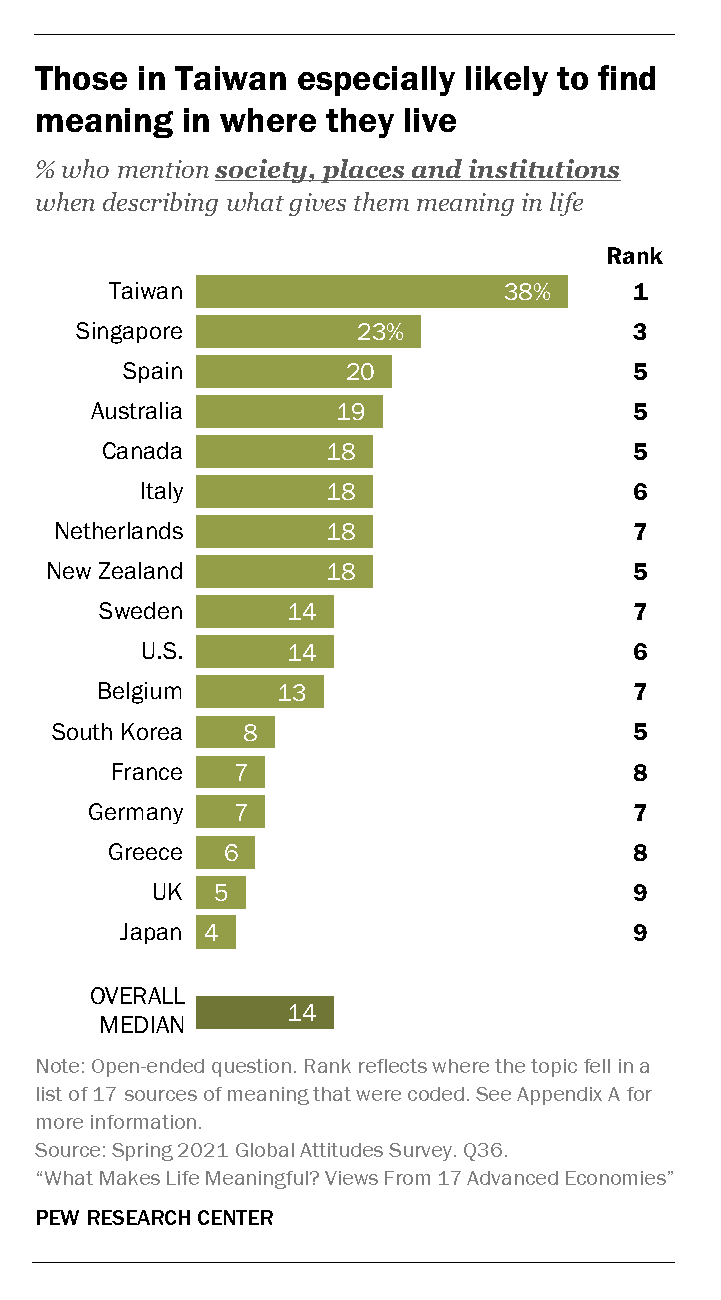

However, an Australian sense of place might be considered higher than many other places (19%) and is only out ranked by Spain (20%), Singapore (23%), and Taiwan (38%).

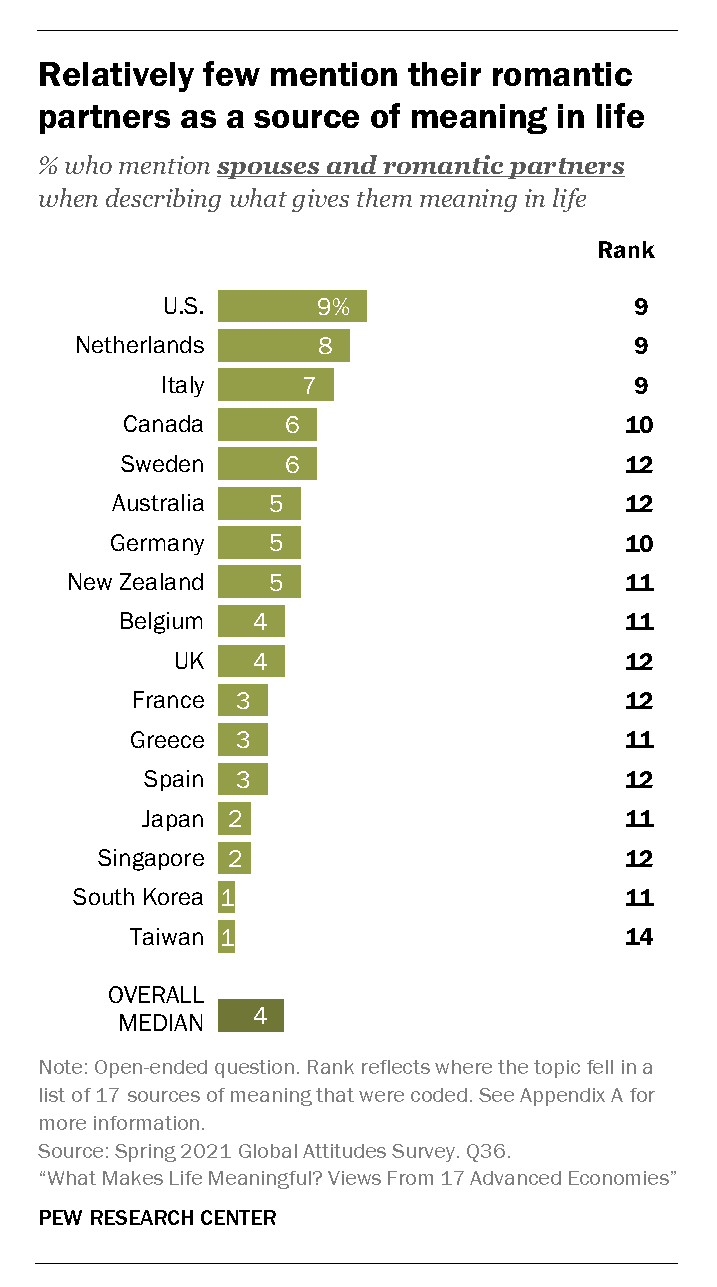

The lowest percentage, but not ranking, are for romance (5%) and religion (4%).

What does this mean? Perhaps, significant minorities at 4-5% who dominate the national story. Religion is certainly related to a certain kind of romance. Marriage ceremonies, and the bride-groom metaphor, speaks to the tie between religion and romance. The challenge is to understand how romanticism binds human evaluation together. Romantics cross religious and secular boundaries but they tend towards the reduction in sociological model. And that is where we have to build up again the pattern of beliefs.

***#***

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- Dear grossly, ethically, corrupted - December 21, 2024

- Thoughts with a Professional History colleague on “Artificial Intelligence” - December 21, 2024

- Stephanie M. Lee on “AI by omission”, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Thursday, December 19, 2024 - December 20, 2024