Although it is not apparent from the philosophical subject matter, this essay is a plea for historians to find the compatibility, for the writing of public history, of the personal and the social. More fashionable historiographies of memoir, oral history, biography, are driving the conversation of history into solipsistic direction. It is the opposite extreme to the absolutist historiography we had at the beginning of the last century.

*****

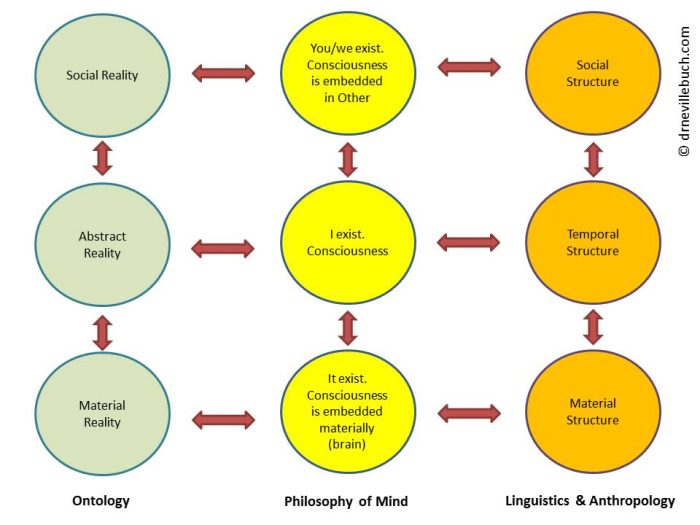

Different fields of philosophy and the humanities investigate the same ideas. The purpose of this chart is demonstrate the interrelation of ideas on consciousness and reality across three fields, and to show that the interrelation rejects the extreme positioning, one which articulates too simplistic dichotomies, and the other to reduce everything to the one idea or thing.

What has been brought together here is the acknowledgement of several working assumptions of philosophers. One is that we can, and ought to, talk of existence, and thus reality. What is spoken of, or referenced, has the possibility of existing or not, of being real or an illusion. Modern philosophy begins with Descartes’ idea that ‘I exist’. There are philosophers who continue to argue that the idea of self, personal identity, or ego, is an illusion. My concern, which seems to have gone unnoticed in the literature, is what it is to have an illusion. ‘I’ believe that the talk of ontological illusion is confused. What is understood as ‘illusion’ is a trick to prevent a reality being perceived. A magician’s illusion is only understood when the trick is revealed against the background of reality. The magician had temporally been successful to elude our view of what she is really doing. When the trick is revealed we see that we have fallen for an illusion because there was something really happening which we were not perceiving. Hence, I cannot see how self, personal identity, or ego, is an illusion in any ordinary meaning. How is it possible to perceive that I do not exist, that I only have an illusion of existing, when it is ‘I’ that is the thinking thing which is doing the perceiving?

There are three possible counter-arguments here. One is to say that it is ‘God’, nirvana, or some ‘Other’ from where the perception lies and ‘I’ am merely the dream or the idea of that perception. The second and third possible manoeuvres are to point to the misapprehension in language. The human species developed language within a cosmology which is fundamentally flawed. One option is to then to dismiss all metaphysics as unworthy of any serious comment. We accept mysteries as mysteries and speak not of them. The other option, and the third manoeuvre, is to conclude that the logic of language does not reveal what is happening, and so we must abandon ‘logicentrism’. Thus we find the post-structuralist ‘postmodernist’. The first manoeuvre is that of traditional religion. The second manoeuvre is a pragmatic or Wittgenstein’s idea of a language game that merely works but does not reveal anything universally. The third manoeuvre is to reject any need to reason and merely assert what is ‘willed’. However, what it is to ‘understand’ rebels against these manoeuvres. If there is surrender to fate, predestination, or to the void, understandably it is something that acts which is not just fate, predestination, or nothingness. Secondly, although what is ‘I’ is certainly contextualised, having particulars temporarily (that is, passing into nothingness) does not make it less real. Satire’s view of consciousness as ‘nothingness’ appears to accept that temporal reality of past-future and future-past, where the present is elusive but still a moment in a process that happens, and that happening or action is understandably ‘some-one’. Finally, one might choose to assert all types of illogicalness as evidence of not being fooled by rational language, but what we have is not merely the ‘power of will’, the cosmic force of the universe, not if there is understanding.

So, in understanding, I exist. There is consciousness. From that central idea, flows the interrelation of other ideas which form the ‘common sense’ worldview, the worldview that is referred to as modernity. It may sound strange to the modern mind (‘I’) but solipsism and immaterialism were once taken as serious options; the former concluding that only ‘I exist’ and the latter that only the idea exist and there is no material substance. In the modern world these anti-realist options have become no more than epistemological exercises; thus, in common usage, no sane person will deny that other persons exist, or that we live in a hard material world, but there are still serious questions of the knowledge of such perceptions. Explaining reality is a little harder, and non-realist options remain. The modern anti-realist, however, has to conclude universality in non-reality. If the class ‘other persons’, or ‘inanimate objects’, do not exist in total, than neither do ‘I’. There are connections which flow from acknowledging consciousness. In pushing out, in time-space, there is action upon something else, or someone else. As well as being described as temporal movement, consciousness (‘I’) understands. It also seeks understanding from others. If I believe that I have understanding from others, there is direct evidence that other persons exist, since what it is to be a ‘person’ involves, not only the capacity to perceive, but the capacity to understand. In that we can also say other non-human species also share a capacity for understanding, but the quality and degree of understanding is different according to cognitive structures. Equally, we are individually conscious of objects where we discern no understanding, nor the capacity. I do not expect that the chair I am sitting on understand what it is I am doing right now. There are material objects, and persons are not material objects in the same way as basic material objects. The difference is consciousness, but it is not to re-introduce ‘the ghost in the machine’ as we have in Cartesian dualism. Consciousness is not a thing; it is the processes of the functioning brain. If we choose not to recognise consciousness, even as a substantially nothingness, as in a process of temporal movement, which is to say it is an existence, then it is difficult to understand how it is to understand anything else.

From an argument of interrelation of ideas inherited on consciousness and reality, it is difficult to see how one cannot but reason a conclusion of an order which recognise self, others, and a material world. One can try package the lot as a complete illusion, dream, or the misapprehension of language, but the order still stands as reality. The impregnability of the total illusion, dream, or language means that the interrelated order is unmoved. What changes, even chaos, is managed within that order. To argue otherwise, is to abandon logic, to abandon reason, and to abandon understanding. And that seems impossible to do.

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- Dear grossly, ethically, corrupted - December 21, 2024

- Thoughts with a Professional History colleague on “Artificial Intelligence” - December 21, 2024

- Stephanie M. Lee on “AI by omission”, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Thursday, December 19, 2024 - December 20, 2024