Popular Culture, Religion, Ethics, and the Compassion of Jesus Christ

When Charles Ringma began street ministry with a Drop-In Centre at the former convent in South Brisbane, which would become known as the Good News Centre, the mission was broadly an intercity outreach. Those who were being outreached were vague groups of persons seen under a range of ‘urban’ or ‘street’ issues. The City Mission movement dates to David Nasmith and the founding of the Glasgow City Mission, Scotland, in January 1826. From there 31 intercity missions were established in North America and Europe included the London City Mission. The Australian movement is traced to the establishment of the Brisbane Town and Country Mission in 1859, the forerunner of the Brisbane City Mission. Australian organisations became ‘non-denominational’ rather than interdenominational, an outgrowth of the Sydney City Mission’s motto ‘Need, Not Creed’. Although the early work included bible distribution, prayers before meals, and auxiliary Sunday School programs, the missions were soft evangelisation, with greater emphasis on Christian charity.

This is the type of evangelisation that Charles Ringma conducted on the streets of South Brisbane. The area was rich in local working-class heritage. It was/is the Labor heartland. The history includes Emma Miller’s radical unionising among the boot factories. Industrial development moved along Montague Road from the 1880s, including the South Brisbane Gas Works, sawmills and a steam joinery. The area was also home to the infamous Lane family among the comfortable middle-class houses on Highgate Hill. Inner-city local areas will be a mixture of wealth and abject poverty. Urban gentrification creates this back-and-forth flow of development and redevelopment, and its social-human losses and gains. At its heart is Aboriginal land never seceded and centred in Musgrave Park. Up until recent times, the reputation of the seedy locations of Musgrave Park and the Stanley Street docklands were of drunk Aboriginal persons and white wharfies and seamen. Prior to the recent stage of urban gentrification, the South Brisbane area was never considered safe at night; that is, until you get to walk up the wealthier Hill End-Highgate ridge.

Figure 1. Craft Time at The Way (Good News Centre). Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The idea of Boundary Street in West End and in Spring Hill, along with Vulture Street and Wellington Road, was that they formed the original boundary of the Town of Brisbane, and, in practice, prevented the Jagera and Turrbal peoples from being within the boundaries at night and on Sundays. Nevertheless, the Aboriginal people were always present. The original placename of West End was Kurilpa, derives from Kureel-pa meaning place of water rats. The distant history to the untrained eye might appear irrelevant to our story. Nevertheless, it goes to the close and equal relationship that Aboriginal persons and white missionaries occasionally shared. For some time in the district, albeit with the atrocious failures of the local institutions in the behaviour towards indigenous folk, there would be small acts of compassionate and just mission. In October 1873, the Primitive Methodist Church opened in Hill End, among the riverside Queenslanders (an architectural style of homesteads). It was joined by St Peter’s Anglican Church (1888) and St Francis of Assisi Catholic Church (1923). Hill End was also the early location of the Baptist Theological College. One church, though, was particularly important for our story. Eventually the Methodists would be located on the centre of the South Brisbane area, on Vulture Street, near the main West End town intersection with Boundary Street.

Figure 2. Lunch at The Way (Good News Centre). Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

A large brick Gothic style church was built in 1885 with a community hall. It would be the site for the Christian social movements of progressivism. From 1948 to 1962 Rev. Arthur Preston was the superintendent minister at Brisbane’s West End Methodist Mission. He was an extraordinary figure as far as the history of social evangelicals goes. Preston has been state director of Crusade for Christ (1949-1952) and Mission to the Nation (1953-1956). He had a weekly radio program on 4BK and wrote a column for the Courier-Mail. For a time, he held Sunday evening services in at the Lyric picture theatre, West End, where, on occasions had around one thousand attending. Of particular interest, Preston, in 1960, began the activities known as the ‘teen cabaret’ at the West End Hall. This was more than the traditional church-organised social dancing. As the name ‘cabaret’ implied, there was a genuine attempt to meet young people in the language and motifs of the sub-culture, albeit minus the ‘seedy’ performance of Jill Haworth (1966) or Liza Minnelli (1972). The narrative is based on novelist Christopher Isherwood’s ‘Sally Bowles’ character, from the true-life dancer, Jean Ross (The Berlin Stories, 1945). There is a lifetime of change between Liza Minnelli and her mother, Judy Garland, known for her childhood performance as Dorothy Gale in The Wizard of Oz (1939). And the same is true for our local story.

Arthur and Clare Preston’s son was the nationally well-known ethicist, Noel Preston, an academic at Queensland University of Technology and an adjunct Professor at Griffith University in the Key Centre for Ethics, Law, Justice and Governance. Noel was a close friend to Charles Ringma. Although theologically they diverged on certain points, they shared the same progressivist outlook of their generation. More significantly, Noel and Charles are the local representations in the imaginative rethink on morality. For their parents’ generation, morality had become too conventional, returning to Victorian pretences which rode on notions of reputation. What was right or wrong was rigidity based on reputational appearance. There was little Christian mercy and much self-righteousness in such judgements. Noel and Charles’ understanding of ethics was in the compassion and care of Jesus Christ, the saviour and healer. The seediness or sordidness and disreputableness of others was appearance. It was not the heart of the matter.

Charles Ringma, as the LifeLine researcher and director of the fledging work at Good News Centre, on the corner of Cordelia and Peel Streets, was greatly shaped by the Methodist-inspired social work at the West End church. Furthermore, it enabled Teen Challenge Inc. to get a good foothold in Brisbane society. Queensland Methodism had been socially popular for two opposite-and-yet-overlapping reasons. Firstly, as in the West End Mission, it was the height of Christian charity and progressivism. Secondly, as in the Wesley Methodist Church in nearby Kangaroo Point, it was an important local centre of the charismatic movement (Rev. Wal Gregory mentioned in the previous essay). The popular relationship was opposing because personalities of former were liberally and outwardly disposed. In the latter the personalities tended to be conservative and inwardly meditating. However, these were opposing dispositions and all personalities had a certain mixture of the two archetypal worldviews at an individual measure. Charitable Catholicism, Presbyterianism, Congregationalism also had this dynamic, as did the Anglicans, the Salvation Army, the Reformed Churches, Lutherans, etc.

Don Wilkinson’s Teen Challenge strategy

The more sophisticated thinking in charity and in ‘evangelical social-class lift’ is what produced the chief mission of Teen Challenge Inc., drug rehabilitation. City or urban mission, however, has different layers of thinking. In 1968-1969 what Charles and LifeLine managers, led by the Brisbane director, Rev. Ivan Alcorn, are thinking, and come to express many issues. There are alcoholics. There are impoverished renters. There are the dispossessed. Different types of abnormal mental health conditions. And then there were increasing numbers of drugged-out ‘street youths.’ It is to the last group that the attention of Charles’ and LifeLine was drawn towards. That was the idea of Charles’ LifeLife-sponsored overseas research tour (Holland, United Kingdom, United States). There seemed that there was a new social problem – drug habits and overdoses among young people. There was, although, a longer history in the same dark heritage. Founder David (Dave) Wilkerson’s brother, Don Wilkerson, worked as the director for the Teen Challenge New York operation 1965-1972. This is where the drug rehabilitation programs were designed and developed.

Figure 3. Paperback copy Cover of ‘Cross and Switchblade’, circa 1963. Source: teenchallengeusa

Dave Wilkerson’s 1958 Call of God Moment in Philipsburg, Pennsylvania, was to youth caught-up in urban gangland culture. It was not specifically a matter of the drug culture, but the two issues were very related. The first Teen Challenge facility, 416 Clinton Avenue, Brooklyn, New York City, was about breaking the drug habit of the first groups of converts – “cold turkey” with prayer. It was a feature of Dave Wilkerson’s The Cross and the Switchblade paperback (1963), the 1965 Life magazine article, and the 1972 film. This was a world away, however, from when Charles Ringma had become a youth leader at the Reformed Church, Toowong, Brisbane, Queensland, at the end of the 1950s. Drug abuse increased as the counterculture of the 1960s took hold. It was an anti-establishment cultural phenomenon, and there were different drug subcultures. Psychoactive drugs were a particular challenge among the flower-power generation (1965-1975 ‘hippies’). Nevertheless, the broader issue had been circling around the ongoing criminal legal status of the recreational drug industry since the 1920s, and mostly around the ‘soft’ drugs, such as cannabis.

Prohibition, though, had clearly been a failed social experiment in dealing with problems of alcohol and narcotic abuse. If you had an anti-establishment counterculture of drugs, psychedelic music, psychedelic art and social permissiveness, state prohibition is not going to work. The line can only be held at regulation. Teen Challenge was in the same boat as charities and urban missions going back centuries (symbol of the ecumenical movement). It was not an agency of the state, but it needed to operate within the law, but the same time it had to secure the confidences and life value of those they were aiding. These types of organisations, to be effective, must be arms-distance to the state and protect the privacy rights of clients. This meant, not so much bending the rules, but ‘hiding’ client activities from state enforcement of the law. Though, with compassionate decisionmakers in government, this is not so much a matter of failing to enforce the law, as a liberal reading of the law.

Nevertheless, the internal condition had to be rigorous rule-following. Between the client and the organisation there was a bound of trust outlined in clearly defined rules. Infractions of the rules usually meant a removal from the rehabilitation program. With Teen Challenge and similar charities, there was the new ethical model developing. The older model was one of lunatic or mental or insane asylum, and it developed into the archetypal prison psychiatric hospital of the 1940s and 1950s (One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, novel 1962, film 1975). It was punitive and moralistic. Deinstitutionalization began with health resorts for the wealthy in the 1920s and grew into the celebrity sites of residential treatment for substance dependence, such as the famous Betty Ford Center (founded 1982). Such programs were no longer about moral judgement and overinflated fears of the insane or weird. It was about medical treatment, spiritual support, and holistic healing.

The leadership of the Teen Challenge, globally, did deliver this type of service, and it is certainly the Christian service of today. However, the historian must be honest to say it did not come overnight, and there were battles within the organisation between reformers and those who lacked the education. Indeed, the medical fraternity was right in their initial skepticism. There was a bigger battle between therapeutic medicine and the conventional discipline. Neither side, as it turned out, had the complete and correct picture, and mistakes were made by both sides in the unfortunate binary debate. Teen Challenge Inc. made mistakes. This matter will be picked up in the other essays, but one matter was very much not a mistake, and that was the educational thinking which was achieved in the first few years of the organisation. In 1981 Charles was appointed a lecturer, to teach medical students on the drug culture at the Faculty of Medicine, University of Queensland.

Figure 4. The new “The Way’, Enoggera Terrace, Paddington. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Philosophy of Outreach, Counselling and Rehab,

The educational program on how you do drug rehabilitation began with Charles’ interaction with Don Wilkerson (TC New York) and Bob Bartlett (TC Philadelphia) in 1971. Charles, though, did not simply import an American model. He adapted it for the local and national conditions. The thinking here was at two levels. The first is the immediate and messy process within the historical past. There is a secondary overlapping of traditional Christian categories of thought – outreach, counselling, and rehabilitation (‘rehab’) – combined with the Australian cultural motifs. The other primary overlapping is the retrospective historical construction, which Charles, as the main philosopher of Teen Challenge described, decades after the gestation, as “Second Order, Cluster Living, Healing, Education, and Advocacy.”

Figure 5. The original ‘The Way’, corner of Peel and Cordeia Streets, South Brisbane. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Outreach

In Christian outreach, the early Teen Challenge workers, such as Terry Gatfield, Peter Jones, Peter Justice, and Geoff and Robyn Dean, drew from the immediate work an informal education. The work then takes what is learnt and redelivered it into formal education. Terry Garfield was an early director of The Way and the His Place Coffee Shop. In the early 1980s he was appointed to the Teen Challenge Board of Management. From 1975 to the mid-1980s, Peter Jones worked as a Teen Challenge administrator. He was the organisation’s newsletter editor and was also appointed to the Board. Peter Justice worked at the Turning Point Coffee House. Robyn Dean was also a TC worker with her partner, Geoff, who is a linchpin in the story. Geoff Dean would much later become a leading academic at the Griffith Criminology Institute, Griffith University, with expertise in policing, security and terrorism studies. In these early years he was the Contributing Editor for Teen Challenge Times. Communication delivered what we now call ‘lifelong learning’, formally and informally. The action here (praxis) spoke deeply within Christian thought of renewing forms, such as baptisms in creeks, rivers, on the beaches, and, allegedly, in the ‘Brisbane city hall fountain.’

Counselling

The same can be said of the early Teen Challenge Counsellors, Chris Adams and Harvey Whiteford. Chris Adams, who studied under Francis Schaeffer, L’Abri, formally got the process going as a trainer at the Youth Workers Training Seminar (14-18 January 1974) held at the West End Methodist Church. Chris became the main drug counsellor during these years. He was another Editor for Teen Challenge Times. He soon established Teen Challenge radio ministry, becoming a minor media personality through his 4MK and 4TO (Townsville) program (Adams had been a radio announcer in Melbourne). The counselling program began as the Outreach and Counselling Training Seminar, Brisbane, in 1973. In early 1980s Harvey Whiteford took the process further and created a recognisable Teen Challenge Counselling Team. By the mid-1980s Neil Paulsen took over as the Coordinator of the Teen Challenge Counselling Service, which was housed at the Head Office in MacGregor Terrace, Bardon.

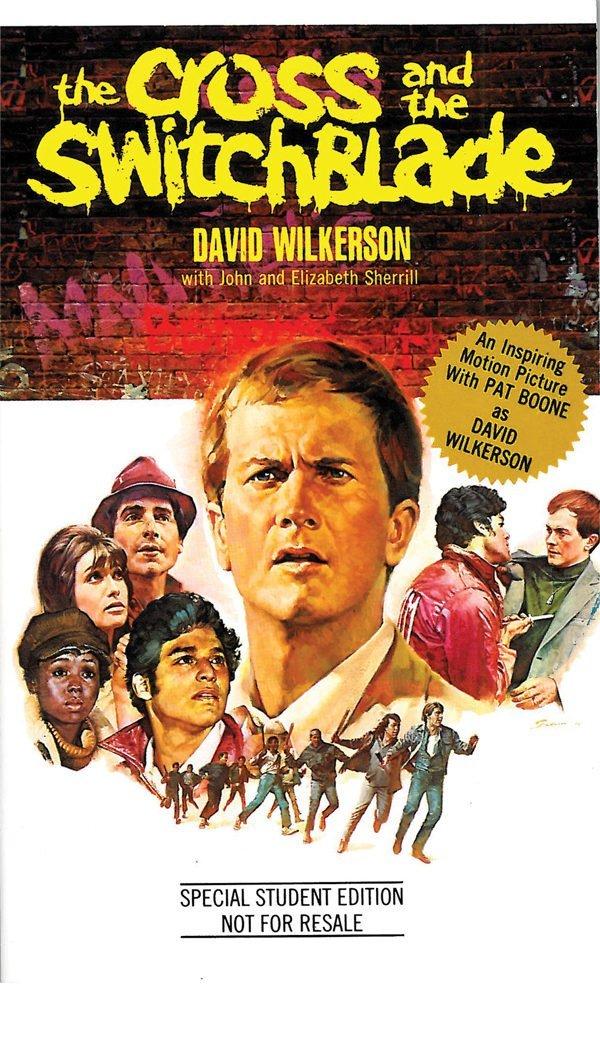

CareLine (the youth telephone counselling service) opened at the end of 1985; a re-formalisation of the service first installed at His Place. Volunteer counsellors that had completed the CareLine Training Course would man these phones. Sarah Hains/Sarah Henderson would be the Counselling Coordinator, Teen Challenge Inc., during the 1990s and into the new century. Sarah Hains, with TC workers, such as Alan Le May, developed the Sandgate-Redcliffe Counselling Service. Alan Le May was on the Board (eventually becoming Chairman) and worked as the Manager, Prevention and Outreach Program, Teen Challenge Inc. He would later be the Executive Editor for the Live Free, The Teen Challenge Magazine, of the Teen Challenge Care (Qld) Ltd, at the Mount Gravatt office. Cross the decades the lessons for counselling from the early years stayed. They were build up, with new training strategies and counselling methods, from the subject-object framing; an application of an individual level for empathy, subjective-listening, and the educative equipping of the client.

Figure 6. Teen Challenge Careline Training. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Rehabilitation

Even among the sub-set of global Christian churches in the 1970s, there were several models of drug rehabilitation. This was the reason for Charles Ringma’s Drug Rehabilitation Study World Tour. On the tour, Charles had an opportunity to see firsthand the American Teen Challenge program at New Jersey. The Way’s (South Brisbane) was a more informal rehab program. It had started only a few years earlier and developed as the Good News Centre. Most of the rehabilitation at this time were in people’s homes where they offered a therapeutic family model. The model began by a personable contract between the household and the ‘client.’ There were a clear set of rules. The rehabilitation rules provide an understanding of the program’s conditions and expectations, and so here is the surviving Sydney TC record:

- No liquor, drugs or tobacco will be allowed on the premises.

- There will be no street talk allowed in conversation nor reminiscing on past experiences.

- No emotional, mental or physical involvement be allowed between residents.

- You will not be allowed to leave the Centre unless under supervision of Teen Challenge personnel.

- If in a mixed group, there will be no pairing or on physical contact allowed.

- You will not be allowed to read any literature which has not been approved by the Director or Counsellor.

- No radio on television programmes will be allowed unless approved by the Director.

- Approved dress to be worn at all times.

- The Director reserves the right to open all mail.

- There will be a two-week trial period before induction into full program.

- You will receive counselling by an approved counsellor.

- Only prescribed medication will be allowed to be taken or on the premises.

- No visitors will be allowed for the first two weeks of the program.

- No phone calls are allowed for the first two weeks.

- All residents must be present at all Chapel services and Bible studies.

- No guest is permitted except at times set aside for this purpose.

- All resident are expected to at times assume regular assignment of duties.

- Any money which you might have on your person will be deposited in a personal fund. Amounts of $1.00 can be drawn out at a time, twice a week. More expensive purchases to be cleared by Counsellor.

- No resident may answer the telephone.

- The Director reserves the right to dismiss any resident who will not fully co-operate with the programme.

This version of the rules, typed-up in the early 1970s, would appear to a contemporary reader as far too controlling, and, indeed, there are questions of its legality under current legislation for privacy, anti-slavery, and human rights. However, even back in the 1970s, this overcontrolling set of rules expressed only the expectation in the first stage of the program. These rules were regularly bent as the trust levels between the house management and the client increased. There was, thus, ambiguity between petty rule following and the permissible relaxations of the rule.

A client could be reprimanded for something as petty as answering a telephone that nobody else seemed to be attending. The therapeutic family model had the underside of periodically treating clients as small children. The earliest rehabilitation workers were Doug Boyle, Peter and Dot Lane, with John Healey appointed Teen Challenge Rehabilitation Director in 1973.

Figure 7. The third ‘The Way’, 106 Simpsons Road, Bardon. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The concept of house management continued in the re-formation of the rehabilitation program in the early 1980s. In 1981 Koinonia Drug Rehabilitation Centre began, with a long-term lease on the 12-bedroom heritage house, located at 95 Banks Road, right on the Graceville riverbank (activities in kayaking). The working household over the years of its operation, included Neil Paulsen, Sue Paulsen, Roy Calic, Lyn Calic, Margaret Robertson, John Moutou, Mike Bellas, Mike Power, Chris Cummings, and Neville Buch. Neil and Sue Paulsen were the first director and partner ‘co-director.’ The remaining first Koinonia team members were John Moutou, Mike Bellas and Mike Power, the Full-Time Male Workers, and Margaret Robertson, Full-Time Female Worker. Other workers frequent the end of Banks Road, such as trainees, Sandra Isles and Annie Sharkey. In the second year Roy and Lyn Calic became the director partnership with their young infant charming the household. Chris Cummings was the Full-Time Female Worker, and Neville Buch (the author) was the Full-Time Male Worker. Different activities were periodically rolled out – informal music appreciation (listening to gospel music), counselling review sessions, occasional games, pottery (with Rita Ringma), shared meals, and occasional outings (e.g., country trips, cinema). The staff members had planning meetings. In truth, at times, it had a chaotic feel, like most households. The upside was that there was little-to-no institutional sense to the program. The downside was the experimental condition – haphazard and much learning-on-the-job. There were recognised successful graduates of the program. Their stories were published in the records by name, and more might be said in the book and the following essays.

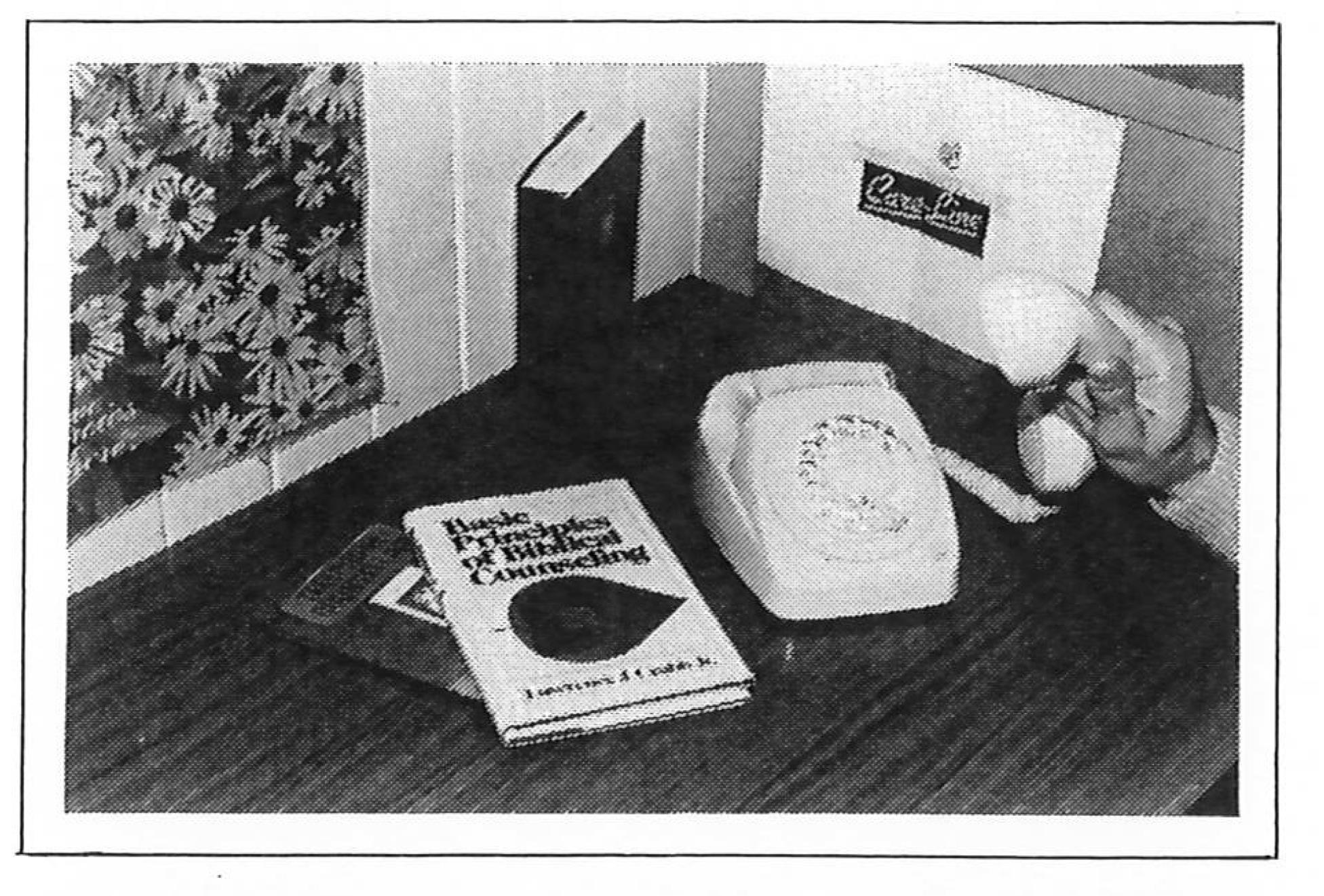

Figure 8. Teen Challenge Fundraising Brochure with Roy and Lyn Calic, Koinonia Managers on the Cover. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The American model in the early period segregated the genders between facilities. In Brisbane during the mid-1970s the same thinking applied. Gary and Lorna Swenson were the manager/co-manager at the Teen Challenge Girls Home in Red Hill. The American way of doing things had some hold. In 1987 Reg Yake, Executive Director Teen Challenge Rehresburg, and Ray Elder, Public Relations Director, United States Teen Challenge Training Centre, ran the “Success Factors in Christian Rehabilitation & Discipleship Youth Workers Seminar,” at the Brisbane City Mission. It is doubtful that the American compatriots understood the Australian model. The American model had originally formulated on a thick urban landscape. By 1977 Teen Challenge Inc. had acquired the Rathdowney Farm, south of Brisbane. As an extension of the rehabilitation, rural living became a significant development in the program. Around 1990 the program was relocated to the Maleny Rehabilitation Farm, which became known as the Sunshine Coast Rehabilitation Centre. Eventually the program became the Teen Challenge Rehabilitation Program at a purpose-built New Life Centre, Cedar Creek in Samford (now the suburb of Cedar Creek). In the late 1990s Judy and Nick Burns staffed the Teen Challenge Rehabilitation Centre at Charters Towers, and in the new century the centre was moved to Toowoomba.

Ringma’s concepts of Second Order, Cluster Living, Healing, Education, and Advocacy.

In his formal interview for the history, Charles Ringma articulated a set of concepts: Second Order, Cluster Living, Healing, Education, and Advocacy. The following sections comes as a cleaner and reedited scripting of Charles’ interview comments as his retrospective thinking.

Second Order

From 1975 to the early 1980s, as the organisation better formalised the Teen Challenge Inc. leadership, it adopted Mother Teresa’s concept of the ‘second order.’ The Missionaries of Charity organisation was the first order. The second order were people “who are living their normal lives” and their contribution to the organisation were as volunteers, often support workers. The example that Charles gave was a support role at Primmer Lodge, where volunteers would have “a couple of the kids [over] for a meal” or play table tennis with the kids or to volunteer on a Friday night… “to take them roller skating or whatever.” This process of the second order “keep staff [demand] at a constructive minimum.” It was not just a budgetary measure for the organisation. It had the primary advantage in the process of normalization for the street kids.

Figure 9. Inside the Valley Activity Centre, circa 1982. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Cluster Living

Jubilee Fellowship, which first met at St. Bartholomew’s Church (Anglican) in Bardon, was an interdenominational service in the afternoon, to allow members to have time to attend other church services on a Sunday. The highlight was the fellowship meal after the service, a common and traditional church activity. However, from Charles’ view, “it was structured and was in terms of a concept called cluster living.” It was a strategy of community-oriented churches to linkup two to four household facilities (e.g., ‘Koinonia’) and family commune homes. Charles’ ideal for ‘cluster living’ was that the households were within walking distance of each other, which is why Jubilee Fellowship, and the Teen Challenge Head Office were in Bardon. The households in a cluster living arrangement could meet a couple of times during the week for morning prayer and for breakfast. An evening social meal usually was held on a Friday night, and they would live in terms of sharing resources. For example, the sharing of one lawn mower and one set of tools and have common gardens. The activities were shared between the rehab and the homes of TC workers.

The downside to the strategy of cluster living was that the ‘fellowship’ and Teen Challenge Inc. organisation drifted apart. It was a long-term problem from the tension between the interdenominational mission and the Assemblies of God (AOG) management; discussed in the previous essay. Governance was largely in the hands of the AOG, but the core TC staff members were involved in Jubilee Fellowship instead of the mainstream churches. The main mission for the AOG churches was outreach (see the next essay). The AOG view was that Teen Challenge’s prime role was to funnel ‘their street kids’ back into the churches. The suspicion was that Teen Challenge was “just hanging on to [its] people.” The reality was that “not every young person wanted to go to Jubilee fellowship” and often did not. Furthermore, whether a young person was converted to Jesus or not, many youths had the wanderlust, coming from southeast Queensland and further field.

Healing

The Charismatic Renewal movement, which accompanied the founding of the Australian TC movement, emphasised what was called ‘divine healing.’ The view of acts of miraculous healing was diverse among different denominations, and even within a local congregation. In fact, in this era, it was becoming a ‘bone of contention’ in the global evangelical world. Non-Charismatic evangelical churches have had significant representation from the traditional medical fraternity, an outcome from basic needs for a missionary calling. The resistant to the charisma was often because evangelical believers felt that the claims for miraculous healing were overstated, if not fraud in wealthy megachurches.

Part of the interdenominational compromise on ‘divine healing’ was to soften the language and liberalise the semantics. Reference to healing in prayer, preaching, and advocacy meant something less miraculous and within the boundaries of traditional medicine. For an organisation such as Teen Challenge Inc. it saved much pain and insults. Part of that process for Charles and the Teen Challenge leadership were references to ‘social healing’. Healing for individuals was still very important, but the spiritual valuation in Teen Challenge was communitarian, if not outright commune. Healing had to be a collective effort, and traditional Pentecost beliefs and practices had always been collective since the Acts of the Apostles.

Teen Challenge sought to bring healing and wholeness to those who were wounded and troubled through drug abuse; the abuse which masked their problems and difficulties. So basically, it was a healing ministry to restore young people to health.

Education

As argued in the last essay, education was a key value for the organisation in these early years. The challenge in the last three decades, as a matter of policy, is that education had to pay its way. The youth train seminars for the public, called the ‘Institute in Basic Youth Conflicts’ was one of the main three sources of income, the other two being the bookshop and the tape sales (distributed recordings of TC speakers and lecturers). This was separate to the free seminars within churches discussing drug and drug related issues. The public seminars were oriented towards dealing with current youth issues and organised for educators and parents.

Figure 10. Advert for Teen Challenge Tape Catalogue, circa 1982. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

As the organisation grew interstate, and Charles functioned as the National Coordinator, the Brisbane-based organisation developed the ‘Institute’ into a one-year full time program, which trained young people on how to do Teen Challenge related ministry. The course was held only one day a week with the training component as an internship between the facilities. The graduates were expected to have time in all the branches of Teen Challenge, including residential work. One of the important educative components was to teach Christian young people how to engage with non-church youth. Often students came to the program as church-sheltered young people, lacking the necessary worldly wisdom. At the end of the program the graduates obtained a youth worker’s diploma.

Figure 11. Teen Challenge emphasis on Training and Education. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Charles and Teen Challenge had an educational bent. “I’ve always believed in the importance of knowing,” said Charles, “and doing after my breakdown, contemplation and action.” This is the meaning of praxis for Teen Challenge Inc. There was no nonsense of making an artificial division between those who are academic and those who are practical. In his (allegedly) “post-Teen Challenge” days, Charles took this a whole new level as a university, college, and seminary professor. Charles would be continuing to help the organisation to rethink its education after his ‘retirement.’ However, it was already happening in the early years. Social Work as a discipline at the University of Queensland was coming to the fore. From the mid-1970s social workers were utilised (as staff and interns; see the next essay). In the mid-1980s, with the Head of the Department, Dr Chris Brown, the lessons of Teen Challenge looped back into higher education teaching and research programs. Around 1984, Ian Goodson and Brendan Scarce were the leading social workers, working out of the Latrobe Terrace head office in Paddington. Teen Challenge Inc. introduced professional development where a staff member, after three years of fulltime work, could take-off a half-day a week, with financial support. The program usually meant part-time study in a Batchelor of Social Work or a diploma in counselling. A half day could simply be to explore solitude and silence with no set outcome. Staff members also enrol parttime in a bible college or a seminary. Charles calls it, “sabbatical space for the staff or volunteers.”

Figure 12. Rita Ringma and Brendan Scarce. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Advocacy

Teen Challenge was well known as the average outreach ministry, from a certain churched perspective. It was much more. One of its other major early activities was drug prevention talks in high schools and churches. It was education, but, retrospectively, Charles sees it as ‘advocacy.’ It is one area which, in memory of grief, still causes Charles great pain, although with the love and forgiveness of Jesus. In both conservative and liberal directions, advocacy was met with cynicism, rejection, and even bitterness. Conservatives “ritually never gets talked about [it].” Liberals often underrated the social dangers. Teen Challenge’s message of compassion during periods of increased drug abuse was not a popular message. Media turned up on the drama and genuine compassion was hidden under the news or current affairs entertainment. Human beings are happy to be entertained but much less opened to being challenged.

In such circumstance advocacy is the voice for the voiceless. For Queensland, with a corrupt police force and with an apparently uncaring Christian Premier, it became a matter of agitating “in terms of the whole prophetic tradition.” Charles tells this story:

…So, what would happen would be that at four o’clock in the morning, the police drug SWAT squad would break into a house and they would, they would marshal all the young people that were living in the house into one room. Then they would search the other rooms for drugs, for money, for guns, whatever. And, and two things then tended to happen. One was, if the drug raid was unsuccessful, so they didn’t find anything… The police would plant drugs and money and sometimes guns in a particular room. And they will then get the young people out of the room and say, ‘Look, this is what we found on your premises, we’re arresting you.’ So, they did that in order to demonstrate statistically how effective they were. It’s all about [a] drug race …are you yielding all of these outcomes? “We’re finding so much hash, and so many pills, barbiturates, and so much heroin, and so much money and blah, blah, blah, etc, etc.”

And so, what happened in was that these young people then would be up for criminal charges. So, the issue is not that they were not drug addicts, you understand I’m saying these young people were drug addicts, but are also young people that we knew and had regular contact with. And over time, when you hear from many, many people, exactly the same story, you begin to think like, hey, something’s really going on here. So, what the legislation was is that if you were a drug dealer, and particularly if you had even a couple of ounces of heroin, you could go to prison for the next 20 years.

There were also stories of watchhouse police falsely recording the amounts of drugs seized. Charles had difficulty getting interest from the mainstream churches, with “Christians who would say, this is really not our problem. We’re just on about evangelization. We’re on about helping people come to healing through our rehab programs. But this kind of stuff is really got nothing to do with us. So, let’s just forget about it.” It was left to Teen Challenge Inc. Brisbane’s top law firm, run by John Robertson was contracted to donating one whole day a week to those that TC brought to the firm. These were young persons who had been charged by the police, but it looked like that the police had planted drugs on their premises. In several cases John Robertson was able to get a leniency plea for those young people, however, some TC clients ended up, unfairly, with a long prison sentence. In which case, Teen Challenge prison ministry followed those convicted.

Charles and the TC leadership approached several state ministers, and finally the Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen. The Premier’s response was dismal: “…ah we’ve got the best police … we are on top of it, don’t you worry about it, we know what we’re doing.” Nothing was done, and the Commission of Inquiry into Possible Illegal Activities and Associated Police Misconduct (the Fitzgerald Inquiry; 1987–1989) would break the political illusion in a Queensland of moral uprightness. It was the media that took the steps on that road, not the churches, and Charles undertook several radio and television interviews in the social justice advocacy, laying out the allegations of police corruption. The public reaction was, in Charles’ words, “all hell breaking loose on our heads…” The Premier was beloved by AOG churches. Joh was a special guest at a number of Assemblies of God churches and conferences. His public denial of Charles’ allegations not only meant that the churches turned their backs on Teen Challenge Inc., but hundreds of persons also suddenly withdrew their support from Teen Challenge.

Several high flying AOG clergy took Charles aside and roundly condemned Teen Challenge for its social justice advocacy. Naive arguments on you are “not supposed to be criticizing the government” and quotations of Romans 13 abounded. The Assemblies of God hierarchy completely abandoned Teen Challenge at that point. Fearmongering took a hold of the congregations and they fell for the classic red-baiting, with Charles and his supporter being labelled as ‘Communists.’ Nevertheless, the Teen Challenge leadership team held strongly to their principles while Christian principles in the AOG churches crumbled. Due to the reduction of support, those who had been with the organization the longest took a significant income cut, but the new staff continued to be paid a full salary. It was tough. In Charles’ words, “When you’re battered you lament. And you grieve. And you hang in as best as you can.”

Terry Lewis, the Police Commissioner, went to prison, as did four other states ministers. Joh Bjelke-Petersen just missed prison from a botched trial, with suggestions of jury rigging, but, from historical judgement, the reputation of the hillbilly Christian Premier would never recover. From the perspective of 2021, it is difficult to understand the behaviour of the AOG and the other hypo-conservative denominations towards Teen Challenge Inc. There has never been an apology or plea for forgiveness. It will be said that Teen Challenge and the TC workers did their duty in the prophetic traditions, and it was their cross to bear. While this might be true, it is a terrible excuse and it will only allow the foolishness to continue in such fundamentalist churches, when the lessons of the history are not taken seriously.

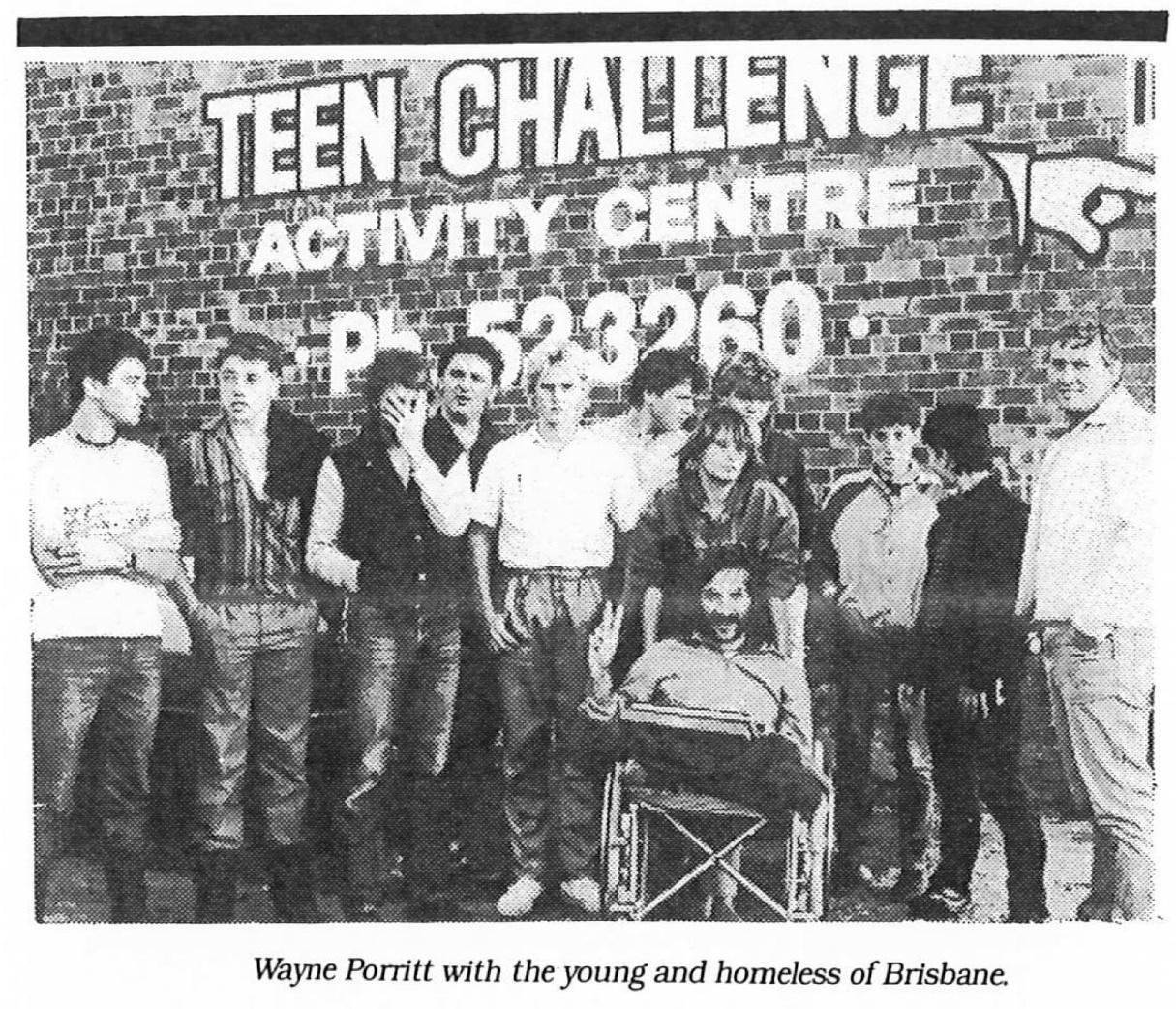

Figure 13. Teen Challenge and Homelessness. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Concluding Remarks

Social workers, such as Ian Goodson and Brendan Scarce, brought a specific way of thinking for the organisation. For Brendan Scarce, this role and thought also included chaplaincy. Another overlapping framing of community. As the head office is moved from Paddington to Bardon, there is in these early years different framing of the work. It is not how organisational managers see the work in the present midst of routines. It is a retrospective judgement of philosophic historians. Historians use different categories which are not apparent in the daily grind, but ‘ordinary’ TC workers were still mindful of, in the brief pause of reflection – class, gender, sexual orientation, and social status. For example, the historical record reveals an ambiguity for feminine partners of male TC leaders, such as Dot Lane and Bev Engwicht. The voice of the past is there but it is challenging to be heard. The women’s history of Teen Challenge, however, is central to Ringma’s concepts of Second Order, Cluster Living, Healing, Education, and Advocacy. In the next essay more will said on the relationship between the organisation and the person.