The task on hand is to overcome misunderstandings of humanism, in the same way that Jean-Paul Sartre attempted to overcome misunderstandings of existentialism; explained in his ‘Existentialism Is a Humanism.’ It is beneficial to examine Jean-Paul Sartre’s statements on humanism, and to rethink on what is meant by humanism. Sartre provided one version, but it has been influential in the general semantics for the last 75 years and more. His partners in ‘French existentialism’, Albert Camus and Simone de Beauvoir, provided different but related versions of humanism. Beauvoir’s ‘softer’ or feminine existentialism explains subjectivity, intersubjectivity, and humanism better, since it had more regard to gendering, and the thinking can be explored in de Beauvoir’s ‘the ethics of ambiguity’ and the autobiographical ‘All Said and Done.’

In the following quotations of Sartre, I have translated gendered references to ‘the person.’ I am not suggesting that gendering is not significant, but if humanism means anything it has to have a commonality in the ‘universal human condition’, as Sartre says.

There are several passages that captures Sartre’s meaning of humanism throughout the original lecture at the Club Maintenant in Paris, on 29 October 1945, and the French book of the lecture published two years later. It was the last part of the lecture/book that captured the main statements of humanism, but it is worth noting the difficulty that Sartre had in giving the audience clarity without tripping himself up. In the section before the main humanist statement, there are two pages which unpacked the concept of freedom [pp. 48-9]. It is not Sartre at his finest. His far harder idea of existential freedom got him into trouble, even as he talked of ‘the freedom of others.’ One thinks of the recent Canadian Truckers’ protests which shutdown Ottawa. Isaiah Berlin’s distinction of the ‘freedom to’ and the ‘freedom from’ would have been more beneficial than Sartre’s ‘freedom of.’ These distinctions run into the problem that Sartre had in the accusation that Sartre held an anti-humanist stance. And so Sartre attempts to explain himself:

“Things must be accepted as they are. What is more, to say that we invent values means neither more nor less than this: life has no meaning a priori. Life itself is nothing until it is lived, it is we who give it meaning, and value is nothing more than the meaning that we give it. You can see, then, that it is possible to create a human community.” [51]

Sartre’s humanism is not libertarianism. Although his philosophy is highly individualistic, he does not place a barrier to a communitarian outlook.

“Some have blamed me for postulating that existentialism is a form of humanism. People have said to me, ‘But in Nausea you wrote that humanists are wrong; you even ridiculed a certain type of humanism, so why are you reversing your opinion now?’ Actually, the word ‘humanism’ has two very different meanings. By ‘humanism’ we might mean a theory that takes person as an end and as the supreme value. For example, in their story Around the World in 80 Hours, Cocteau gives expression to this idea when one of his characters, flying over some mountains in a plane, proclaims: ‘Man is amazing!’ This means: even though I myself may never have built a plane, I nevertheless still benefit from the plane’s invention and, as a man, I should consider myself responsible for, and honored by, what certain other men have achieved. This presupposes that we can assign a value to person based on the most admirable deeds of certain men. But that kind of humanism is absurd, for only a dog or a horse would be in a position to form an overall judgment about person and declare that he is amazing, which animals scarcely seem likely to do — at least, as far as I know. Nor is it acceptable that a person should pronounce judgment on humanity.” [51-2]

Although Sartre stated that this masculine humanism is absurd, in the original text he spoke in the masculine language. Perhaps in 1945-7 we can forgive Sartre, but the point is mooted. The more significant point is that Sartre stated that there were two different meanings to humanism, and thus created an unnecessary binary. There are several versions of humanism, and, in fact, it is how one ‘cuts the cake.’ To ‘cut the cake’ indicates that categories, concepts, models, are differently shaped from the dissecting of material life. ‘To eat the cake’ is to make the existential choice to consume in the intellectual awareness of one of the slices. ‘To have the cake,’ perhaps, is to consider the paradigm and to walk away, another existential choice. Sartre said, it is not acceptable “a person should pronounce judgment on humanity.” This is not completely true, as Sartre stated earlier,

“…people tell us: ‘You cannot judge others.’ In one sense it is true, in another not… Nevertheless we can pass judgement, for as I said, we choose in the presence of others, and we choose ourselves in the presence of others.” [46-7]

As I indicated, it would be a mistake to see Sartre as a libertarian.

“Existentialism dispenses with any judgment of this sort [holistic view of humanity or an overall judgment about person]: existentialism will never consider person as an end, because person is constantly in the making. And we have no right to believe that humanity is something we could worship, in the manner of Auguste Comte. The cult of humanity leads ultimately to an insular Comteian humanism and — this needs to be said — to Fascism. We do not want that type of humanism.” [52; Sartre’s own emphasis]

According to Sartre, humanism is not a religion, and certainly not a secular religion as seen in political ideologies of any doctrines, including democracy, even as it be our existential choice.

“But there is another meaning to the word ‘humanism.’ It is basically this: person is always outside of themself, and it is in projecting and losing self beyond themself that person is realized; and, on the other hand, it is in pursuing transcendent goals that the person is able to exist. Since person is this transcendence, and grasps objects only in relation to such transcendence, the person is themself the core and focus of this transcendence. The only universe that exists is the human one — the universe of human subjectivity. This link between transcendence as constitutive of person (not in the sense that God is transcendent, but in the sense that person passes beyond oneself) and subjectivity (in the sense that person is not an island unto themself but always present in a human universe) is what we call ‘existentialist humanism.’ This is humanism because we remind person that there is no legislator other than self and that the person must, in their abandoned state, make their own choices, and also because we show that it is not by turning inward, but by constantly seeking a goal outside of oneself in the form of liberation, or of some special achievement, that person will realize themself as truly human.” [52-3]

Not only is existentialism a humanism, but it is also a personalism. Personalism is an intellectual stance that emphasizes the importance of human persons. One can trace the concept back to earlier thinkers, back two or three centuries, in various parts of the world, and constructing into various versions of personalism. Friedrich Schleiermacher first used the term personalism (German: Personalismus) in print in 1799. Sartre is providing one version of personalism, what it is to be a person.

“From these few comments, it is evident that nothing is more unjust than the objections people have brought against us. Existentialism is merely an attempt to draw all of the conclusions inferred by a consistently atheistic point of view. Its purpose is not at all to plunge mankind into despair. But if we label any attitude of unbelief ‘despair,’ as Christians do, then our notion of despair is vastly different from its original meaning. Existentialism is not so much an atheism in the sense that it would exhaust itself attempting to demonstrate the nonexistence of God; rather, it affirms that even if God were to exist, it would make no difference — that is our point of view…” [53]

Humanism cannot be reduced to religion, theism, atheism, or nihilism. That is clear from what Sartre is saying. Certainly, there are variants of humanism which align to these concepts. However, what all of the French existentialists tell us – Camus, Sartre, and de Beauvoir, and among others – is that these variants come too short in the outlook of humanism.

Jean-Paul Sartre (1947; 2007). Existentialism Is a Humanism, Yale University Press, New Haven, Conn. p. 51-53. Gendered words replaced by phrasing in ‘the persons’ or other substitutes.

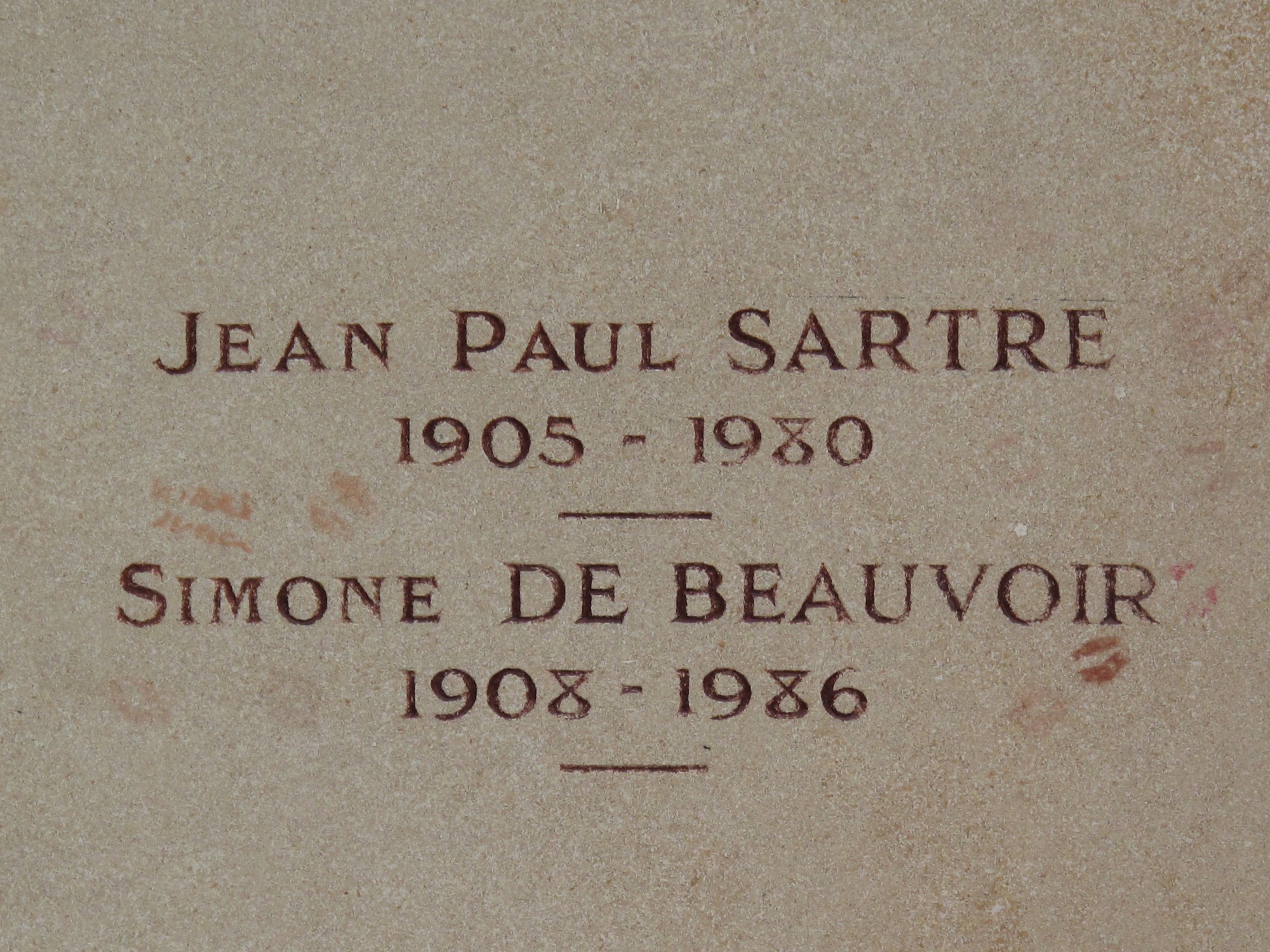

Image: Close-up of the Tombstone of French existentialist philosopher Jean Paul Sartre and of the Feminist thinker Simone de Beauvoir at the Montparnasse cemetery in Paris. Photo 141956785 © Aduranti | Dreamstime.com

I dedicate this blog article to my existential partner, Ruth Elizabeth Buch (nee Lohmann, 1961-2016).

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- J. D. Vance’s Insult to America is to Propagandize American Modernism - July 26, 2024

- Why both the two majority Australian political parties get it wrong, and why Australia is following the United States into ‘Higher Education’ idiocy - July 23, 2024

- Populist Nationalism Will Not Deliver; We have been Here Before, many times… - July 20, 2024