“… Last Friday, Salem Media Group announced that it had removed the fabulist film 2,000 Mules from its platform and said it would no longer distribute either the movie or an accompanying book by the right-wing activist and Trump-pardoned felon Dinesh D’Souza. It also issued an apology to Mark Andrews, a Georgia man whom the film had falsely depicted participating in a conspiracy to rig the 2020 election by using so-called mules to stuff ballot drop boxes. After being cleared of any wrongdoing by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, Andrews filed a defamation lawsuit in 2022 against D’Souza, Salem, and two individuals associated with a group whose analysis heavily influenced the film.”

Ken Bensinger, ‘2,000 Mules’ Producer Apologizes to Man Depicted Committing Election Fraud, The New York Times, May 31, 2024

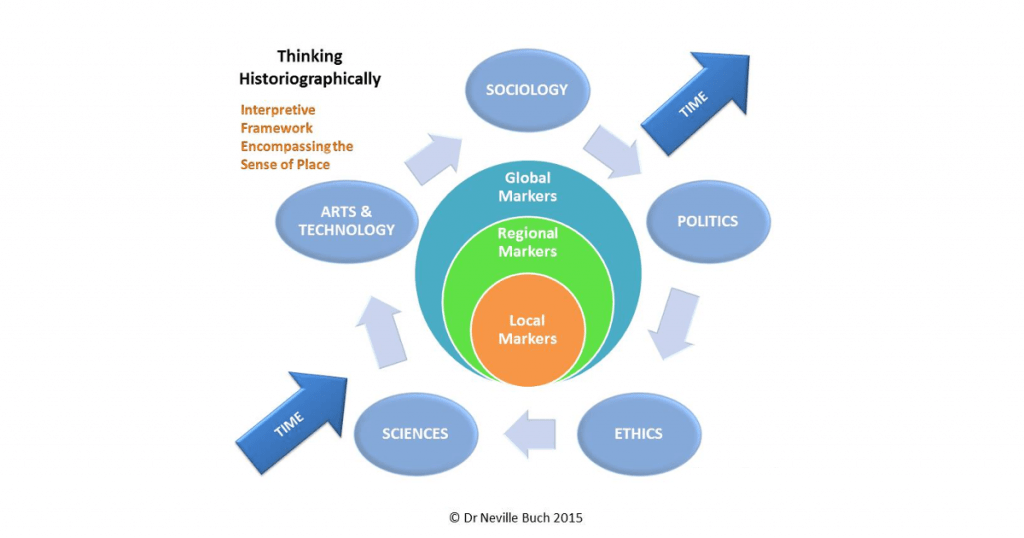

Graph: Thinking Historiographically 1024×538.

History spirals. There’re at least four main steps in the spiraling action.

1. Widely-Believed Falsehood:

Recently, we have seen the widely-believed falsehood in the the fabulist film 2,000 Mules. Films have been a platform of widely-believed falsehood since the beginning of Hollywood at the turn of the 20th century. In the last half century, though, films have become more bluntly politically-charged. The Washington’s Watergate-charged atmosphere of the 1970s, not ceasing from the late 1960s other American political intrigues, made the messaging very blunt. On the Left, was the later Emmy Awards-winner history drama TV movie, KENT STATE, 1970 (2023 Monarch Films). The film dramatization could not be done for a decade, so painful had the event been in American cultural life. The leftwing roots meant a romanticism which did not help to get an accurate historical sense for its present. On the Right, were the American 1970s evangelical apocalyptic movies. On the first uneducated glance, these films may not appear to be politically-charged. However, the pre-millennial message of A Thief in the Night (1972), A Distant Thunder (1978), Image of the Beast (1981), and The Prodigal Planet (1983) brought the themes of the Rapture and the Tribulation, where either politics was portrayed as a-politically irrelevant (itself a politically-charged message) or politics was portrayed as a secular government out to destroy the religion of the devout. The films were alarmist for the political agenda to destroy the leftwing (other) agendas of the late 1960s and 1970s. The falsehood was widely-believed but was always one large section of the society. In the United States it is estimated that supporters of Donald Trump is only one-fourth of the population. It estimated 30 to 35% (90 to 100 million people) are Evangelicals in the United States. Australia is not remotely distant to such widely-believed falsehood. Even as there has been significant resistance to Americanization in Australia, recent militant protests during the short era of the global pandemic shows a sizable section of the Australian population captive to far right narratives.

Ken Alder in an article called, “A Social History of Untruth: Lie Detection and Trust in Twentieth-Century America,” wrote:

…the efforts of twentieth-century American experts to oblige recalcitrant men and women to tell the truth about themselves. How different are these two enterprises [detecting lying and trust]? When Albert Einstein inscribed above his fireplace the motto, ‘‘Nature’s God is subtle, but He is not malicious,’’ he surely acknowledged as a corollary the possibility that people might be malicious, if also sometimes subtle. It is this latter corollary that has inspired the proponents of an American science of lie detection. Their premise is that while a human being may tell a conscious lie, that person’s body will ‘‘honestly’’ betray his or her awareness of this falsehood…(1-2)

2. Accountability:

There is accountability to teachers, mentors, supervisors, and others who guide us through life. Well, at least there once was. Accountability has undergone significantly challenges in the last six decades. On one level it is a perennial theme in “thumbing one’s nose,” not at authority, but each at their own sense of comprehensive responsibilities. Persons always “thumbing one’s nose at authority,” and that is healthy, if it is also not very effective. However, responsibilities that one’s owns is far more than the comfort that is given in the “freedom of speech.” To take responsibility, that is, to be accountable, rewards the person with integrity of being a person. In other words, it is normative mental health. The challenge is understanding “responsibilities that one’s owns.” Central to holding it together is the truth of the knowable and unknowable. The glue of integrity is knowable and it is also unknowable. Contrary to populist bullshitting, epistemology has not destroyed what we might designate as knowledge nor the capacity to know. Any technical epistemic justification, somewhere along the trees of argumentation, would be suffice. So, be accountable, and stop the bullshitting. Still, there are many matters which are unknown, and it is still undecided whether matters will ever be known (so, unknown). The glue chemistry for the unknowable is humility.

Jonathan Gorman in article called, “Historians and Their Duties,” wrote:

We need to specify what ethical responsibility historians, as historians, owe, and to whom. We should distinguish between natural duties and (non-natural) obligations, and recognize that historians’ ethical responsibility is of the latter kind. We can discover this responsibility by using the concept of “accountability“. Historical knowledge is central. Historians’ central ethical responsibility is that they ought to tell the objective truth. This is not a duty shared with everybody, for the right to truth varies with the audience. Being a historian is essentially a matter of searching for historical knowledge as part of a an obligation voluntarily undertaken to give truth to those who have a right to it. On a democratic understanding, people need and are entitled to an objective understanding of the historical processes in which they live. Factual knowledge and judgments of value are both required, whatever philosophical view we might have of the possibility of a principled distinction between them. Historians owe historical truth not only to the living but to the dead. Historians should judge when that is called for, but they should not distort historical facts. The rejection of postmodernism’s moralism does not free historians from moral duties. Historians and moral philosophers alike are able to make dispassionate moral judgments, but those who feel untrained should be educated in moral understanding. We must ensure the moral and social responsibility of historical knowledge. As philosophers of history, we need a rational reconstruction of moral judgments in history to help with this. [added emphasis]

3. Falsehood Retreats:

There are fools who argue that since perception is the mental filter we can never know truth from falsehood. There two basic reasons why this is a bullshit argument. First, perceptionism is not the opposite or disjuncture with Object-ism (not to be confused with Ayn Rand’s Objectivism). There are objects in the world, and we know that there are objects in the world by the fact of perception. It is perception that can tell us whether we have a true object perceived, or whether the ‘object’ is an illusion. Perception can lead to illusion in the mental reflection (i.e. the thought about the thought), thus, we have the falsehood. On the other hand (or in another direction of the brain firing), we can reasons ourselves to the truth from perception. The question is what truth is being established. For each truth proposition is relative to the other, until it networks out into a holism (Willard Van Orman Quine). Now, those who follow Rand “get very hot under the collar” at this point. However, Quine can help us out. He advocated a behaviorist theory of meaning which meant that the distinction between analytic and synthetic statements are defended ambiguously, undermining verificationism, and we have to retreat to behavioural judgements. For most epistemologists with the contemporary fallibilism, Quine’s critique is untroubling. Life, and knowing life, will always be ambiguous. The point is that Rand is very wrong in her Objectivism, we ‘know’ that we do not understand objects directly, otherwise nobody could even talk about perception. Quine helped by demonstrated that in stating ‘truth’ of analytic and synthetic statements we can never completely be there. Indeed, Quine is being inconsistent between his behaviouralist semantics and his scientific holism.

Now, there will be idiots who dismiss the above paragraph because it simply logic and epistemology, and not, as they proclaim, politics, history, or sociology. However, the above paragraph works perfectly well as political philosophy. An argument of falsehood might go like:

- There are those Right/Left persons who are all relative and cannot accept the Object in my politics;

- Such persons are confused in directly “perceiving” the Object;

- Conclusion — “I am right (correct) and they are wrong.”

W. Speed Hill in an article called, “Doctrine and Polity in Hooker’s ‘Laws’,” wrote:

If he is read today at all, Richard Hooker is read as the author of a single work, the massive treatise Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity. Yet his other writings, if one includes Chapters iv-vi of Book vi, the “tract of confession” over which the dispute arose at Hooker’s death, amount to one-quarter of his extant work. Largely unexplored, they reveal the essentially inward bias of his mind, and they set forth, independently of the disciplinarian context of the Laws, the doctrinal assumptions that underlie its defense of established polity. From the perspective of these non-Polity writings, the Laws , for all its length, its wealth of illustrative detail, and meticulous argumentation, is simply an application in extenso of more general principles that Hooker enunciates elsewhere… But to see these doctrinal issues as Hooker himself saw them is to see the arguments of the Laws in a perspective nearer to Hooker’s own, one less colored by the pervasively controversial bias of his lay collaborators…[added emphasis]

4. Historical Forgetfulness:

In “Buckley’s Chance, Cultural Thinking of Trumpism, and History” I have stated:

The mob’s logic — all minority positions — is x = zero (liberalism offers nothing for me personally), so non-x (fascist thinking). Forgive my poor logic writing here. The better logicians are welcome to formulate the mathematical language in its better expression. But the point is historiographical solid. Historical forgetfulness leads a population into the spiral history theory of stupidity.

What is needed? Conversations and agreements to the compatibilism, as I have explained in my short piece, Finding Peace from the Culture-History War: A Historiographical Message for the Times.

My concern is that we have Buckley’s Chance to turn matters around, and we are trap on the spiral of eternal return (see links above, “the spiral history theory of stupidity”; each word here has a different link in the phrase, and the same with other phrasing above).

What humans need and want of life is Peace, if also Survival and Flourishing. This is what we have to keep foremost to Mind.

The last stage of the spiral is historical forgetfulness. And the cycle of the spiral begins again in the historical memory which is not re-discovery, as direct realism, but the shades of ideas brought back to a new life.

David Michael Kleinberg-Levin in an article called, “The Court of Justice: Heidegger’s Reflections on Anaximander,” wrote:

… In his commentary, Heidegger draws on Nietzsche’s thoughts about justice, the will to power, and nihilism to formulate an interpretation of the fragment that connects it to the epochal history and destiny of being. This “ontological” interpretation, constructed in a compelling reading of the history of philosophy, requires that Heidegger first address the historicism and “onto logical forgetfulness” prevailing in historical consciousness and historiography, in order to begin thinking towards the possibility of another epoch of being, releasing us from the injustice that is inherent in the ontology that rules in the present historical dispensation. Although Heidegger avoids moral prescription, he cannot avoid critical entanglement in the moral-juridical sense of justice, despite his claims and protestations, since, as his own account of the fragment implies, justice and ontology must be inseparable. Reading Heidegger’s commentary in relation to Benjamin’s philosophy of history, I argue that Heidegger’s reflections on justice suggest a narrative of tragic hope that resembles Benjamins configuration of justice in his reading of the Baroque mourning-play, where the hopelessly fragmented and imperiled image of justice is revealed as emerging from a Leidensgeschichte fatefully bound up in the continuum of a Schuldgeschichte [added emphasis]

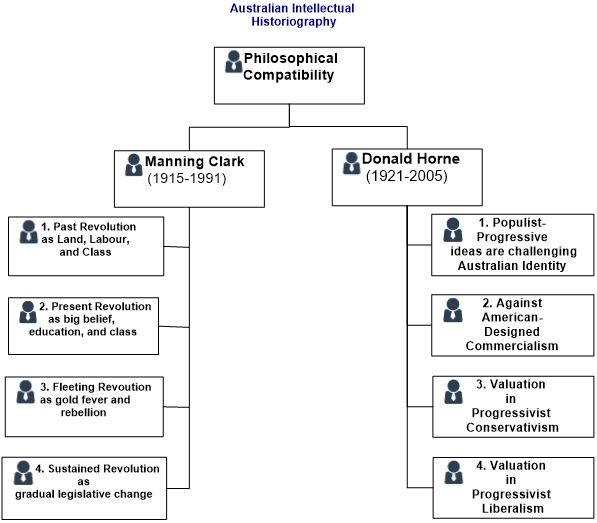

Conclusion in Australian Intellectual Historiography

On the eternal returns, as an intellectual historian examining the previous era of 1945-1985, we find, in the revaluations (Nietzsche’s perceptionism reconsidered), that Manning Clark and Donald Horne, from the two ends of the political spectrum, had already given us four stages of spiral historiography.

See, Progress and Popular Thinking in the United States & Australia 1945-2020, and, Geo-Political Debate in Australia: An American-Australian Relational (Intellectual-Cultural) Reading.

How stupid we are in not paying attention to the intellectual histories which just spiral around, a little forward, and a little retreat.

REFERENCES

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- Dear grossly, ethically, corrupted - December 21, 2024

- Thoughts with a Professional History colleague on “Artificial Intelligence” - December 21, 2024

- Stephanie M. Lee on “AI by omission”, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Thursday, December 19, 2024 - December 20, 2024