Bélanger (2011:14) outlines the different directions that Dewey and Thorndyke, and others, came into the teaching, learning, and assessment theories. These differences are important to understand why machine learning is not learning. In learning tasks where personable judgements are to be reported, nearly all of the schools Bélanger outlined would support a view of learning assessment being consensual, descriptive, verbally owned (‘I believe…’), and respectful to the personable effort made. Only the behaviourist school separated with this ‘fairness in assessment’ approach since the mid-century.

From the literature that Bélanger identifies, Hidi (1990) provides a clear argument for a self-reporting of the subjective evaluation from the objective teaching, which is has been the standard understanding of human learning since the mid-century. Other forms of ‘learning’, of animals and machines, are mimicking behaviour without self-reflections; humans may reduce themselves to the dispositional level. Hidi demonstrates the key human factor of ‘interest’, which is self-reflection:

Dewey (1913, 1916) was one of the first North American psychologists to emphasize the important role of interest in learning and to argue that interest should be seen as a result of an interactive process between an individual and his or her environment: In interest the “self and world are engaged with each other in a developing situation” (Dewey, 1916, p. 126). Dewey, and later, Thorndike (1935), both acknowledged that learning is influenced not only by personal interest but also by the interestingness of tasks and objects. Bernstein (1955), in an early and isolated study on reading comprehension and interest, also emphasized that interest is derived from the characteristics of the reader, factors inherent in the text, and the interaction of the two. This interactive view forms a common basis of much of contemporary interest research (e.g., Fink, in press; Hidi & Baird, 1986; Prenzel, Krapp, & Schiefele, 1986; Renninger, 1990; Renninger & Leckrone, in press). (1990: 550)

When we talk of machines and animals “learning” or having “interest”, it is a human projection in the language that humans created. The evaluation is in the self-reflection, and thus, learning. Calfee (1981) supports the argument by outlining the history of the education theories and practices:

Behaviorism. At mid-century, the behaviorism of Thorndike dominated American psychology. The approach focused on the relations between stimulus and response. The theoretical efforts Spence amounted to curve-fitting overlays; they were close kin of There was great emphasis on learning, on the acquisition of over brief periods of time. Members of this school assumed the basic learning principles of broad generality over organisms and Rats, pigeons, undergraduates, children, mental retardates-the the learner mattered little. Tasks were selected for convenience t-maze, button press, nonsense syllable).

The behaviorist tradition was marked by a driving optimism (Thorndike, 1910) partly justified by the practical utility of some of the methods findings. …

Two features distinguished the new paradigm. One was the infusion of new techniques for theory development. I have already mentioned Estes’ stimulus sampling theory (Estes, 1959; Neimark & Estes, 1967), which evolved into a system of remarkable proportions. In addition, there were developments in signal detection theory (Green & Swets, 1966), rational decision making (Simon, 1980a, reviews the history), transformational grammar (Miller & Chomsky, 1963), and information theory (Garner, 1962.) The second feature of the psychology was a renewed effort to understand the nature of mental activity. Psychologists had originally relied on introspection to understand the mind. The method informs us about the content of thought, but reveals precious little about the process of thinking. By judicious combinations of innovative theory and methodology, cognitive psychologists tried once more to trace the mind’s pathways. Reaction time became a critical indicator-S. Sternberg’s (1963) paper, a major advance, showed that it was possible to identify cognitive stages by decomposition of reaction times (also cf. Chase, 1978; Posner, 1978; R. J. Sternberg, 1977).

The main point is that it became legitimate to talk about what was going on in the mind. Mathematical psychologists began to discuss learning as changes in mental states and in the level of storage. With the gradual emergence of the computer as an analogy, it became increasingly natural to talk about short-term and long-term memories, control processes and executive routines, storage capacity, decay rates, selective filters, and the like. (1981: 4, 5). [Add emphasis, so the point is read carefully]

I note too that Calfee (1981: 19) states that “One of the chief functions of education is to provide the individual with a wide array of conceptual and semantic frameworks for arranging knowledge in organizational networks that differ substantially from the results of natural experience.”

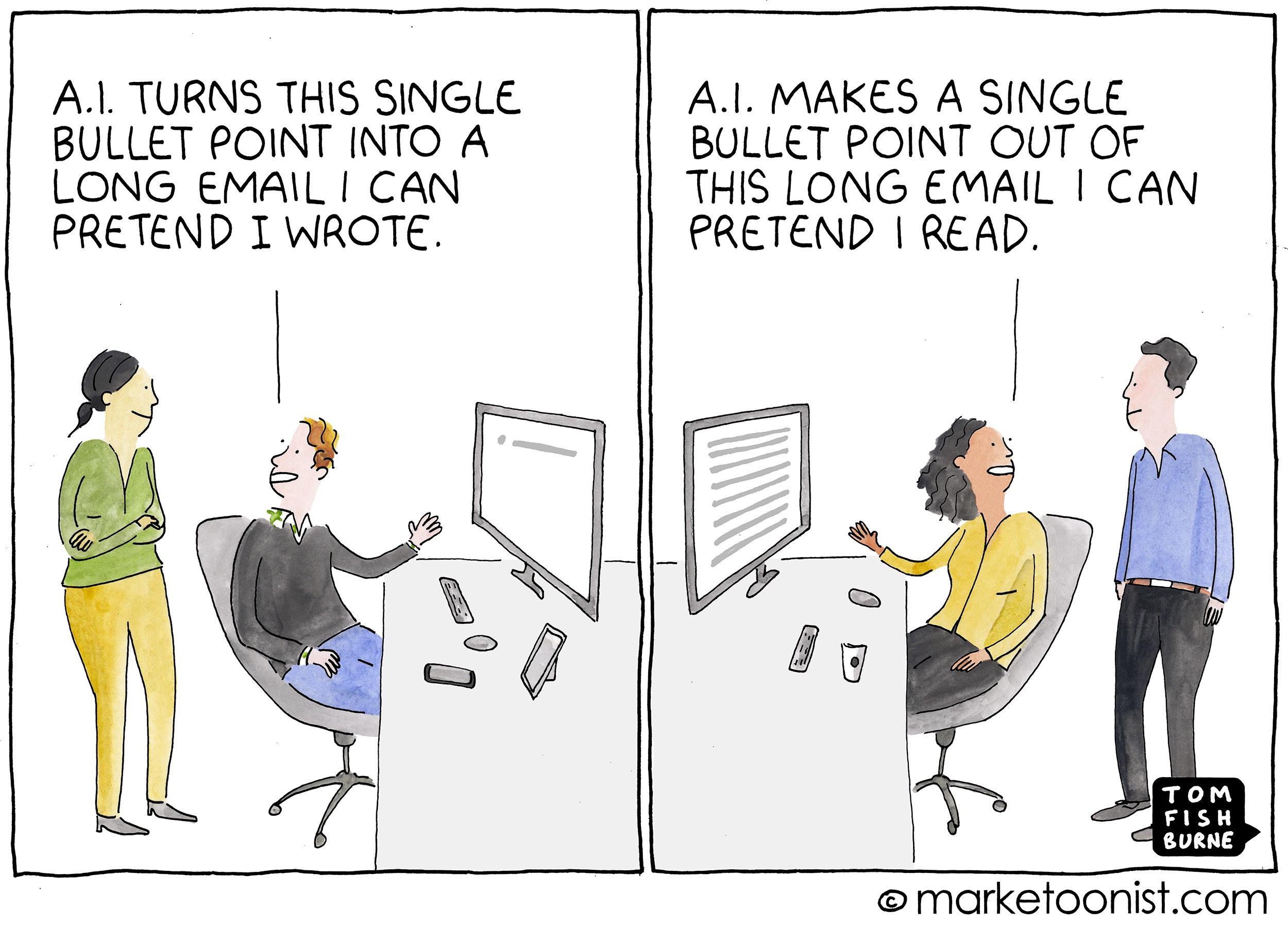

This is why I am arguing that machine learning is not learning. The I.T. Industry lacks this level of multi-disciplinary knowledge in its misnomer usage of the term, “machine learning.”

REFERENCES

Bélanger, P. (2011). Introduction to Adult Learning Theories. In Theories in Adult Learning and Education (1st ed., pp. 13–16). Verlag Barbara Budrich. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvbkjx77.5

Calfee, R. (1981). Cognitive Psychology and Educational Practice. Review of Research in Education, 9, 3–73. https://doi.org/10.2307/1167182

Hidi, S. (1990). Interest and Its Contribution as a Mental Resource for Learning. Review of Educational Research, 60(4), 549–571. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170506

Image Source: Marktoonist (Tom Fish Burne). Licenced No. 27175, 28 March 2023, US$100

Featured Image: Machine learning concept as modern technology. Photo 134730803 / Machine Learning © Elnur | Dreamstime.com

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- Dear grossly, ethically, corrupted - December 21, 2024

- Thoughts with a Professional History colleague on “Artificial Intelligence” - December 21, 2024

- Stephanie M. Lee on “AI by omission”, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Thursday, December 19, 2024 - December 20, 2024