This is a research note to preserve copyright and notice to this new and substantive thesis of the Anglo-American major belief-doubt systems, since the seventeenth century, which at the end of that century expanded, and transformed, the power of the English monarchy to a new entity known as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The constitutional and national development coincided with the securing of the fledging English colonialism in North America, with entry, in the next century (18th) into the waters and landmass of the Asia-Indian-Pacific spheres. The concept of colonialism is not limited nor unique to the English-speaking worlds. However, in both threatening and beneficial ways, it produced Anglo-American belief systems, and both for the powerful colonisers and the disempowered colonised.

These belief systems, which includes its necessary skepticism (doubt), have usually been 1) called ‘ideology’, and 2) boxed as categories of ‘religion’ and ‘secularity’. Both these outlooks are problematics and are based on gross intellectual misunderstanding. First, ‘ideology’ is commonly used as a swearword to dismiss systems thought: out-of-hand, as (to be frank) a ‘blood-minded’ and ignorant defence mechanism. So, to be clear, references to ‘ideology’ and ‘ideological’ are used here merely as references to systems thought, either for good or bad. Secondly, the studies-in-religion field, more than half century, has clearly demonstrated that the hard categorisation between references to ‘religion’ and ‘secularity’ are false. Those who continue in that ‘categorical mistake’ (Gilbert Ryle, The Concept of Mind, 1949) are usually culture-history warriors.

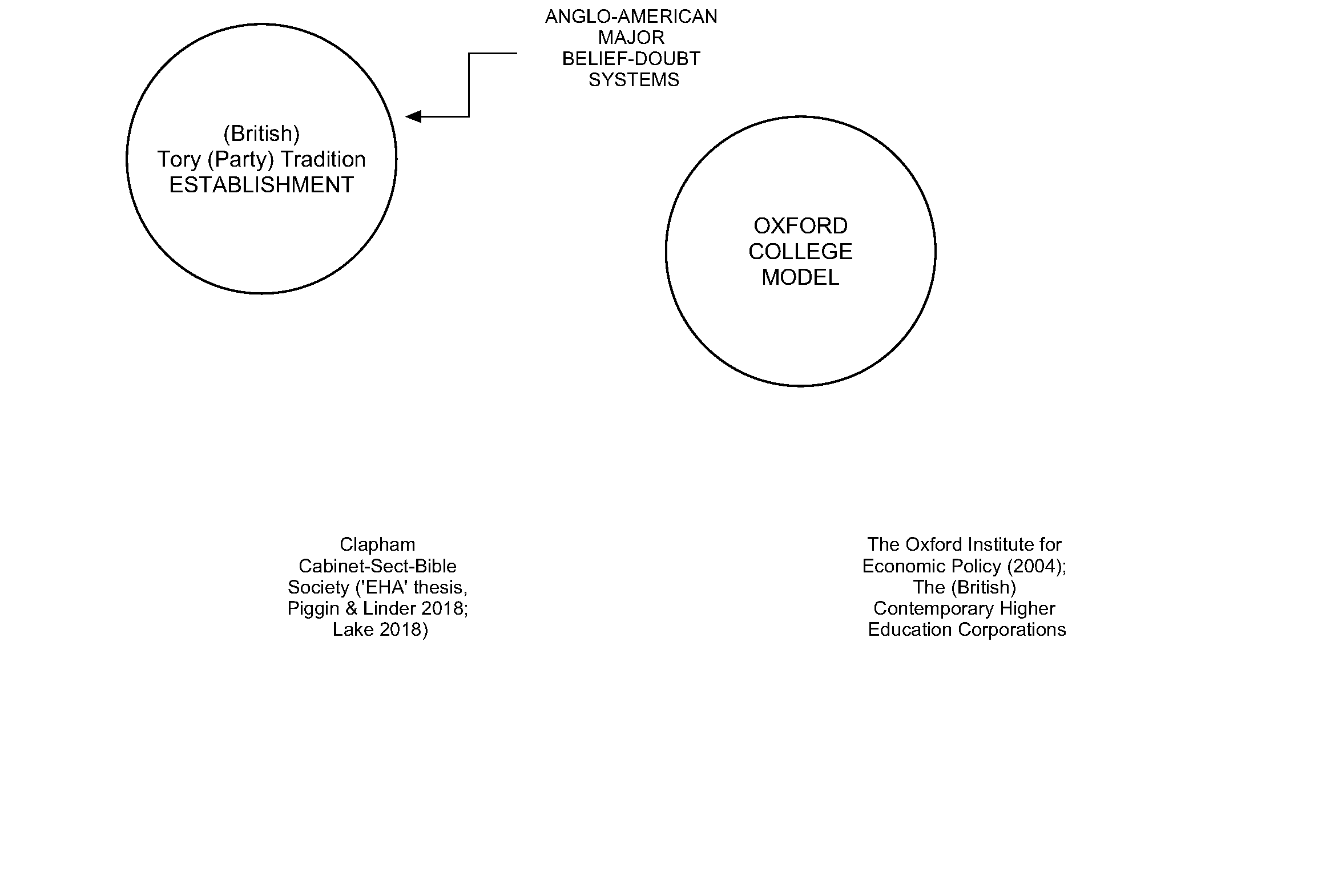

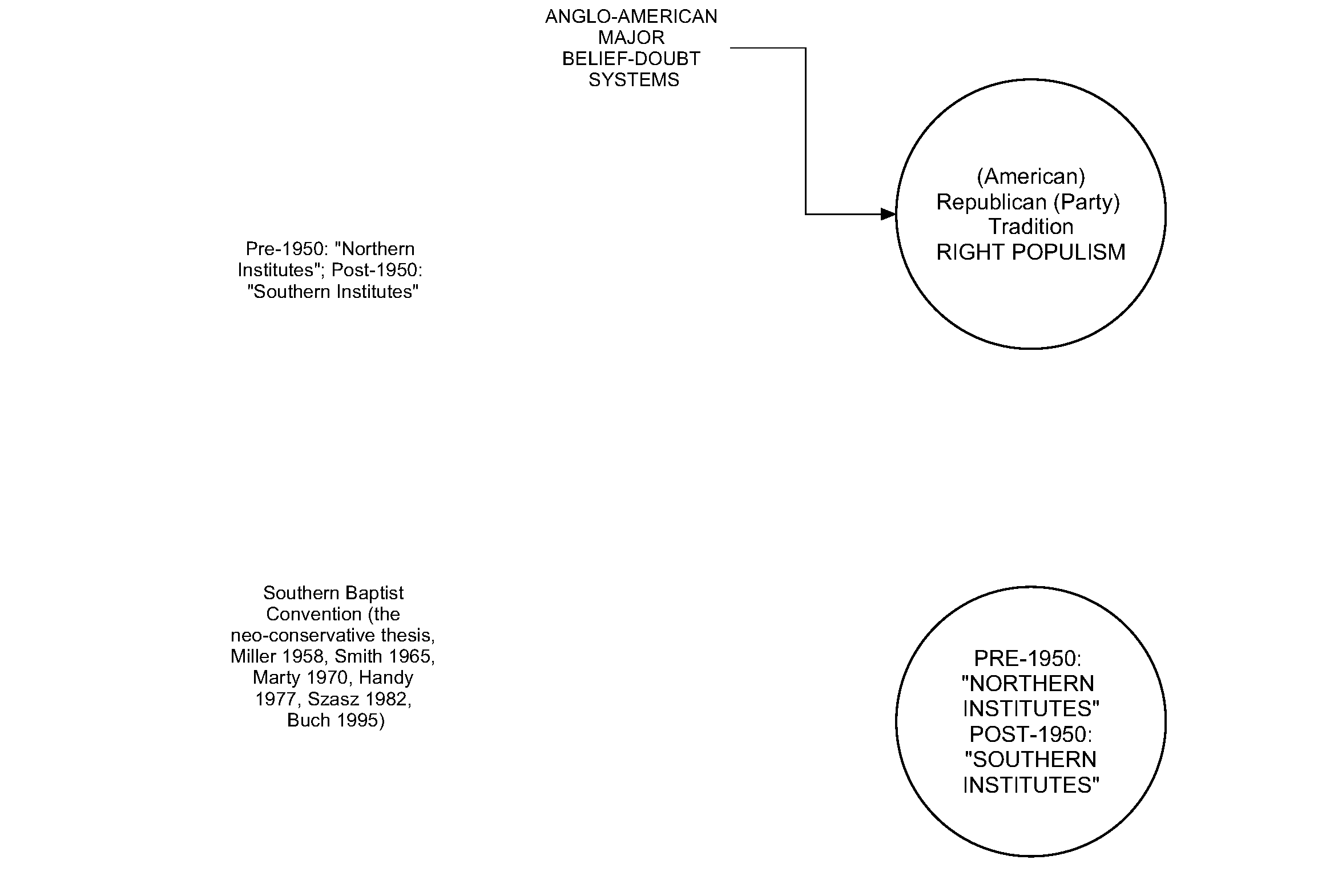

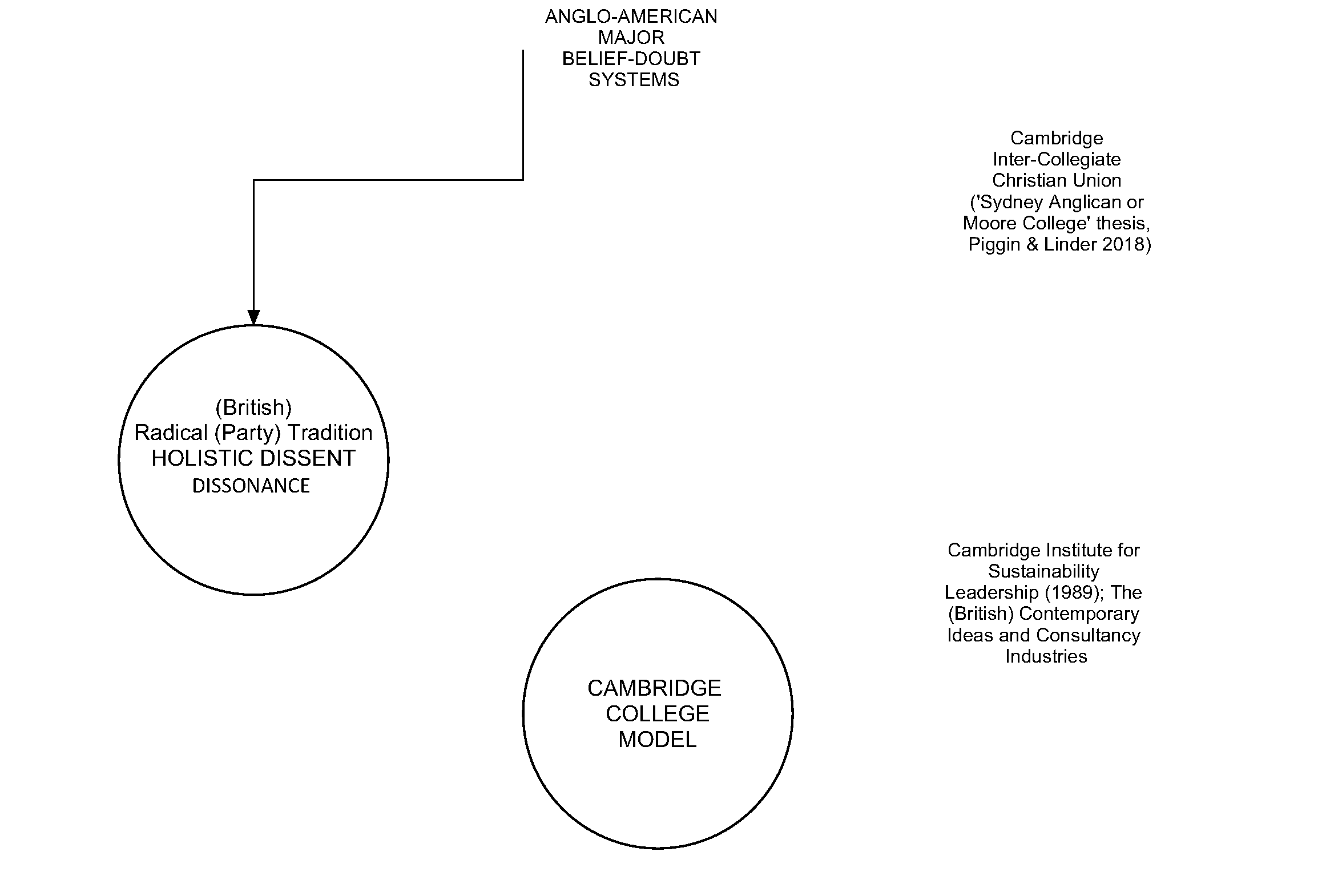

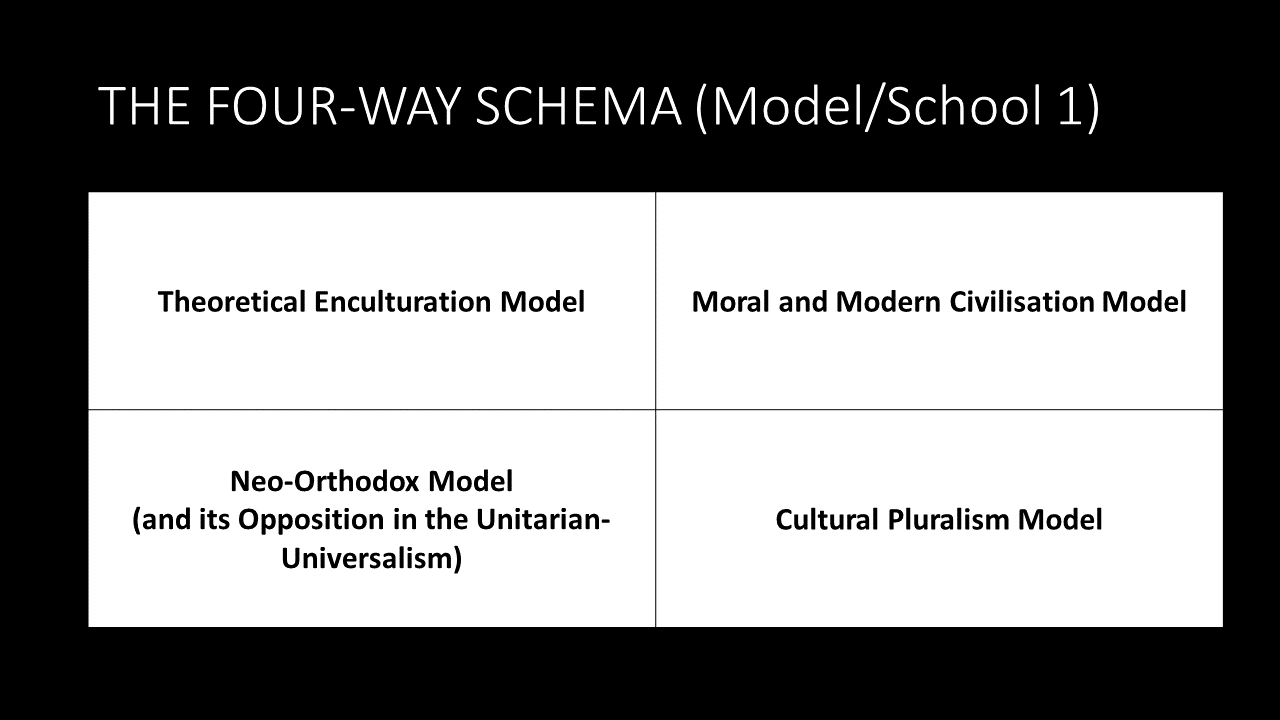

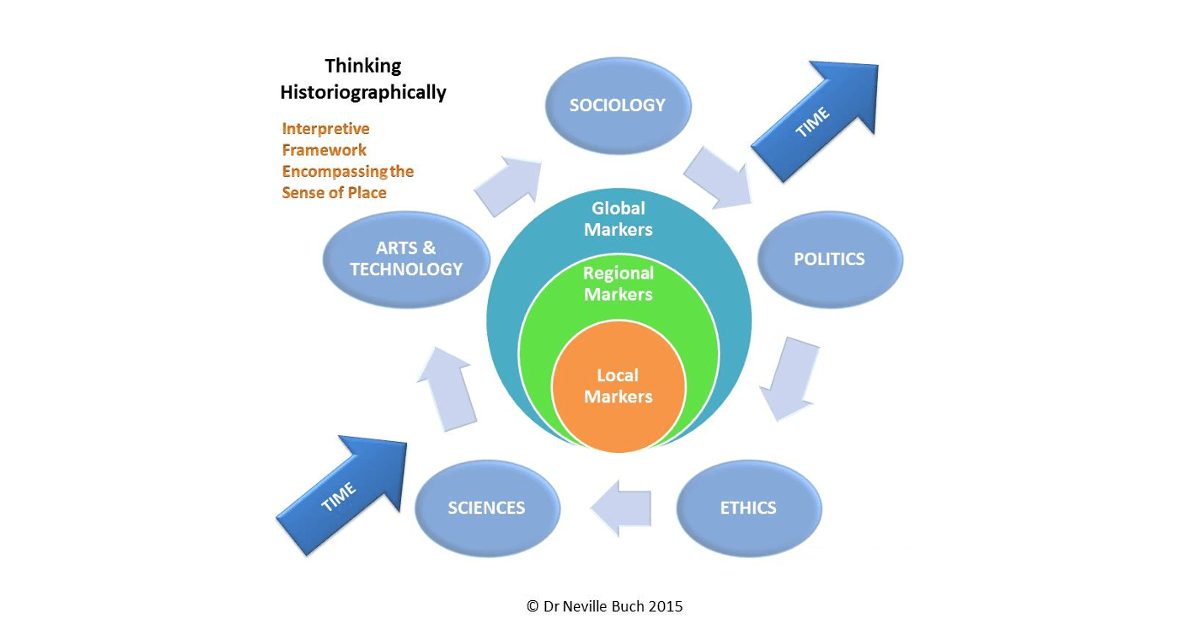

The structure of the research to 1) identify a basic worldview, 2) describe a model of that worldview which usually ties the evolutionary thread to a global university school or college or networked institutes. From those two steps is a selection of one key example in 3) the historic Evangelical World and one in 4) the (‘secular’) Corporate World, usually in a dual sense of a singular institute or school of thought and an industry or corporate grouping. In this way, a web of belief can be both described and explained.

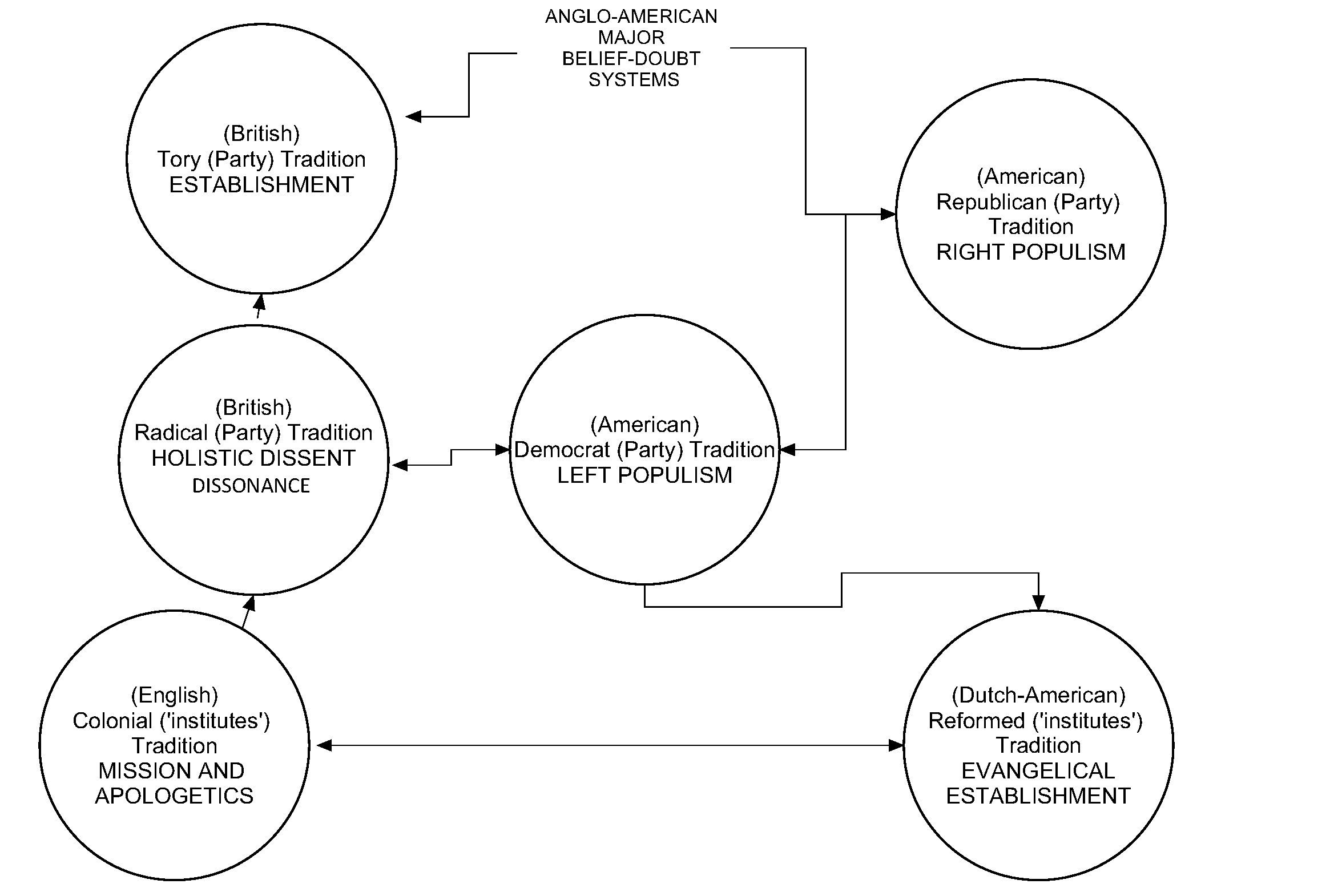

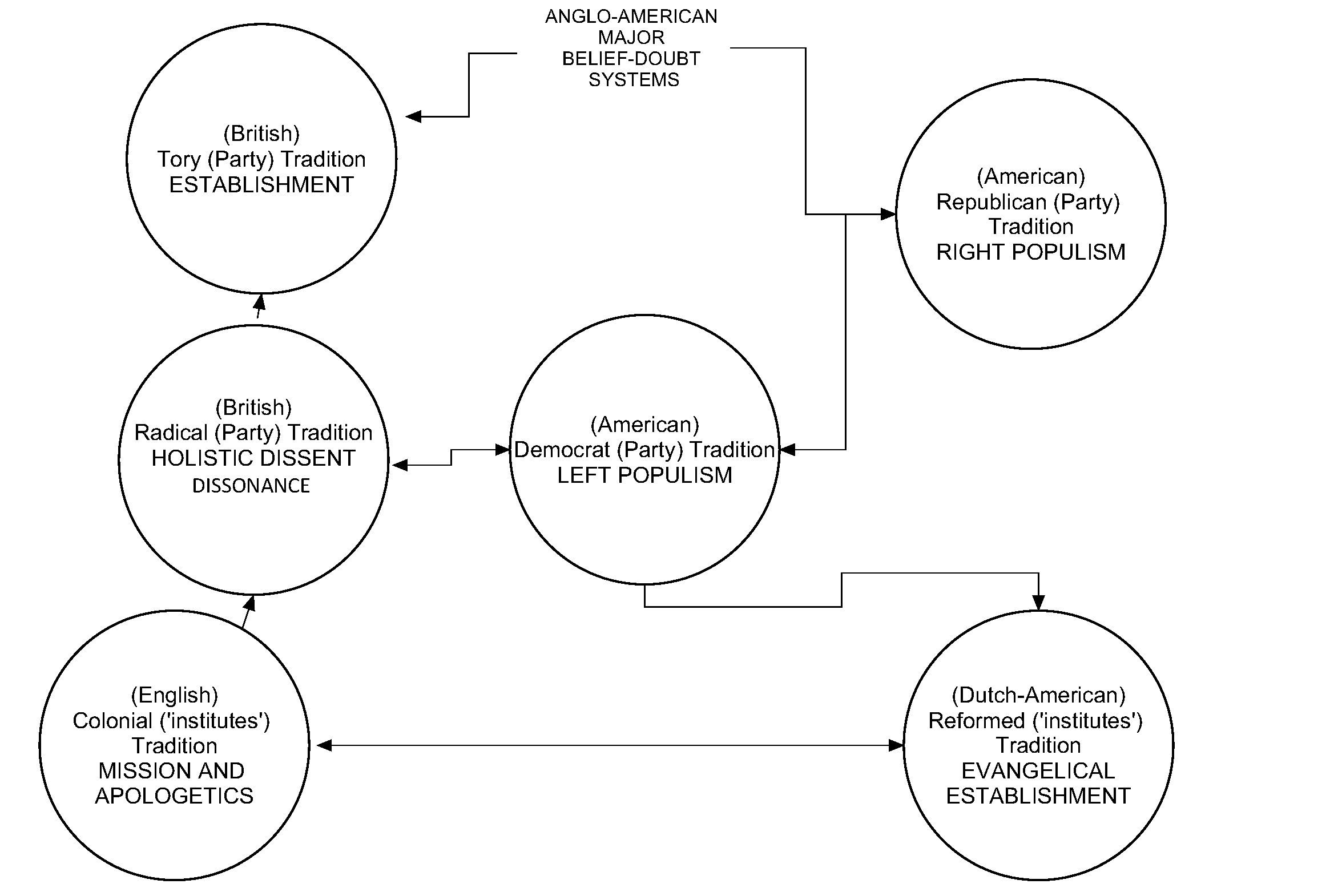

There are six basic socio-political worldviews. The descriptors identify a cultural reference, the usual ‘socio-political’ name, its usual status as either a political party or a social institute, describing the worldview as a tradition, and the usual tag as a common language by-word (in that order of the descriptive phrase):

- The (British) Tory (Party) ESTABLISHMENT

- The (American) Republican (Party) Tradition RIGHT POPULISM

- The (British) Radical (Party) Tradition HOLISTIC DISSENT Dissonance

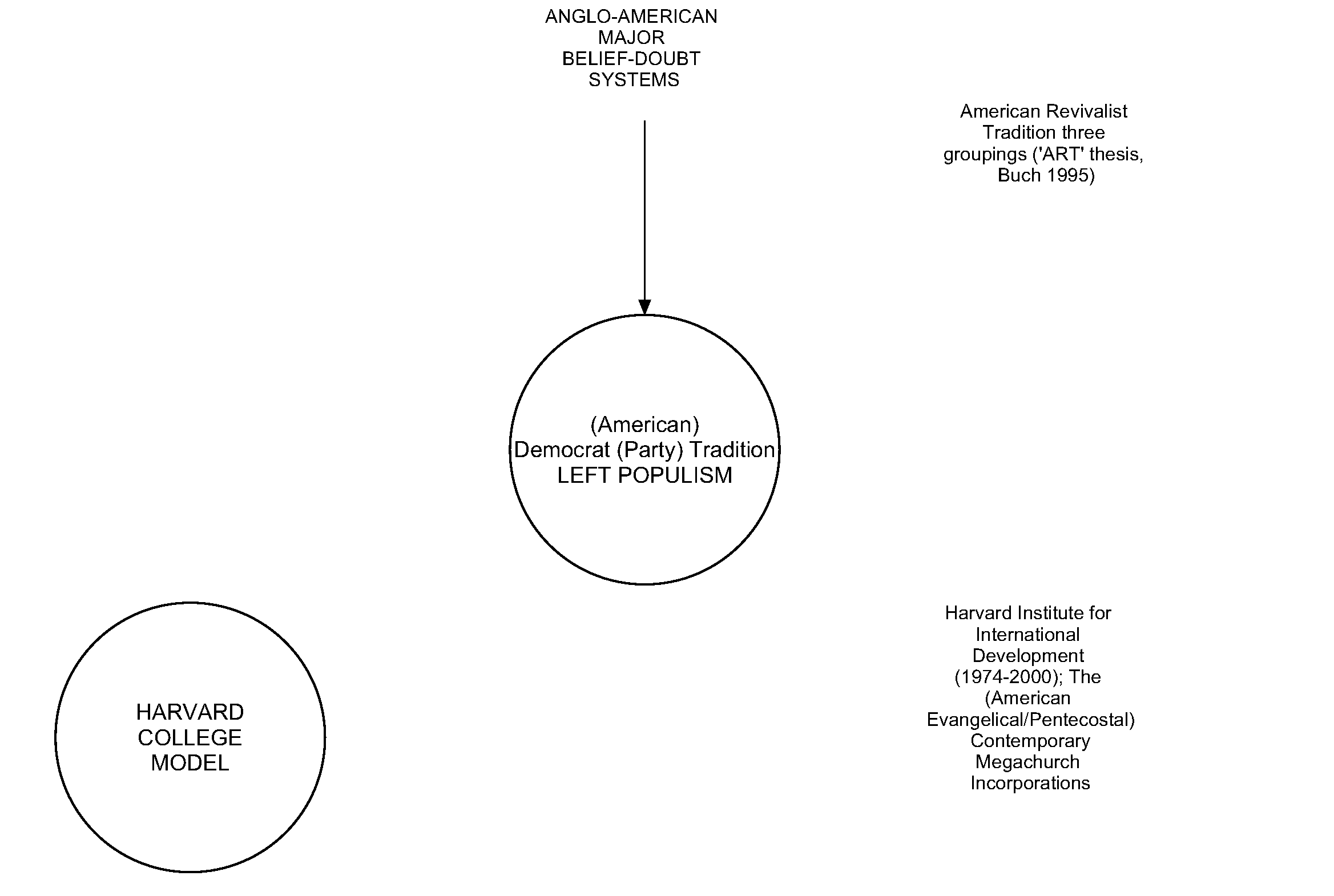

- The (American) Democrat (Party) Tradition LEFT POPULISM

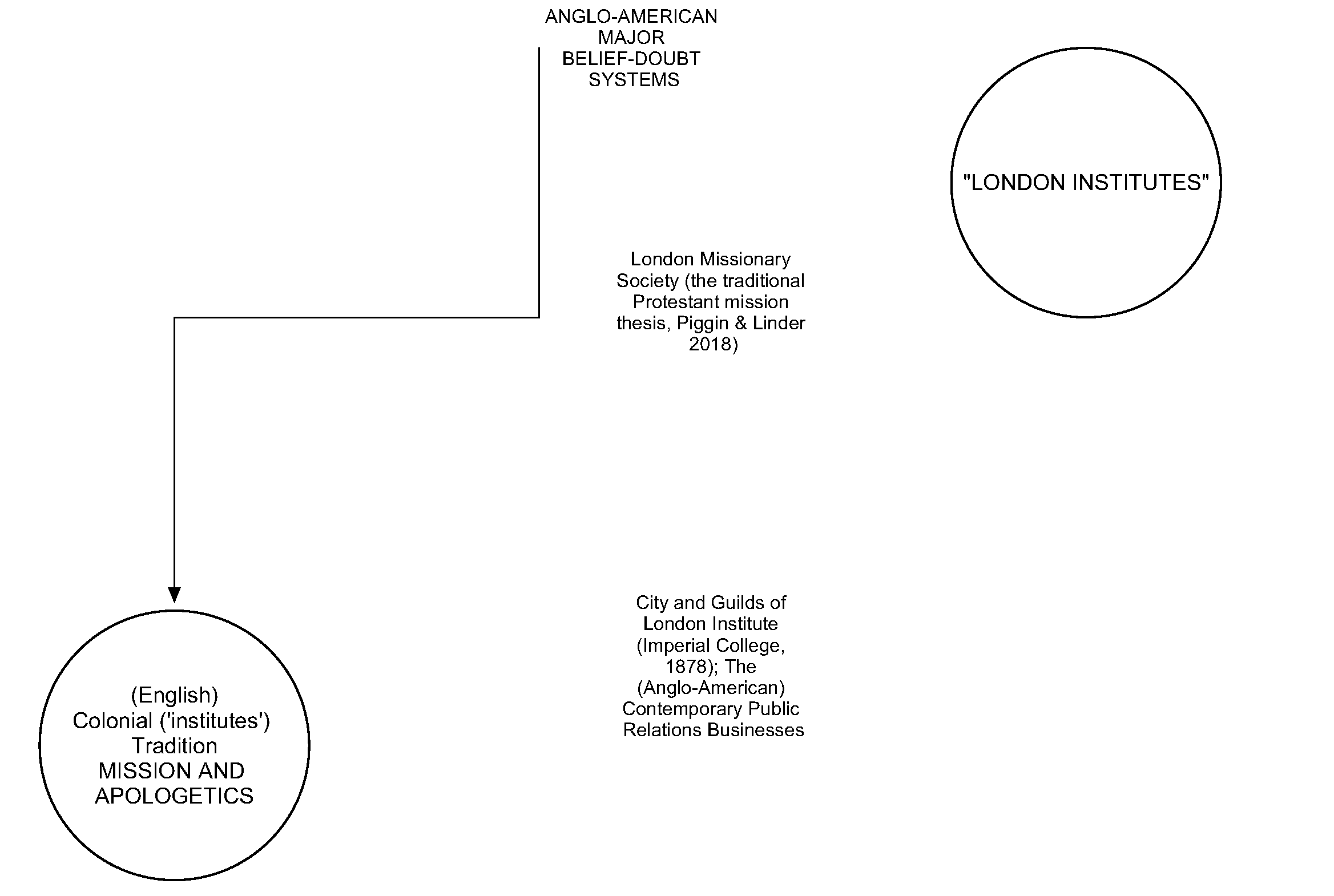

- The (English) Colonial (‘institutes’) Tradition MISSION AND APOLOGETICS

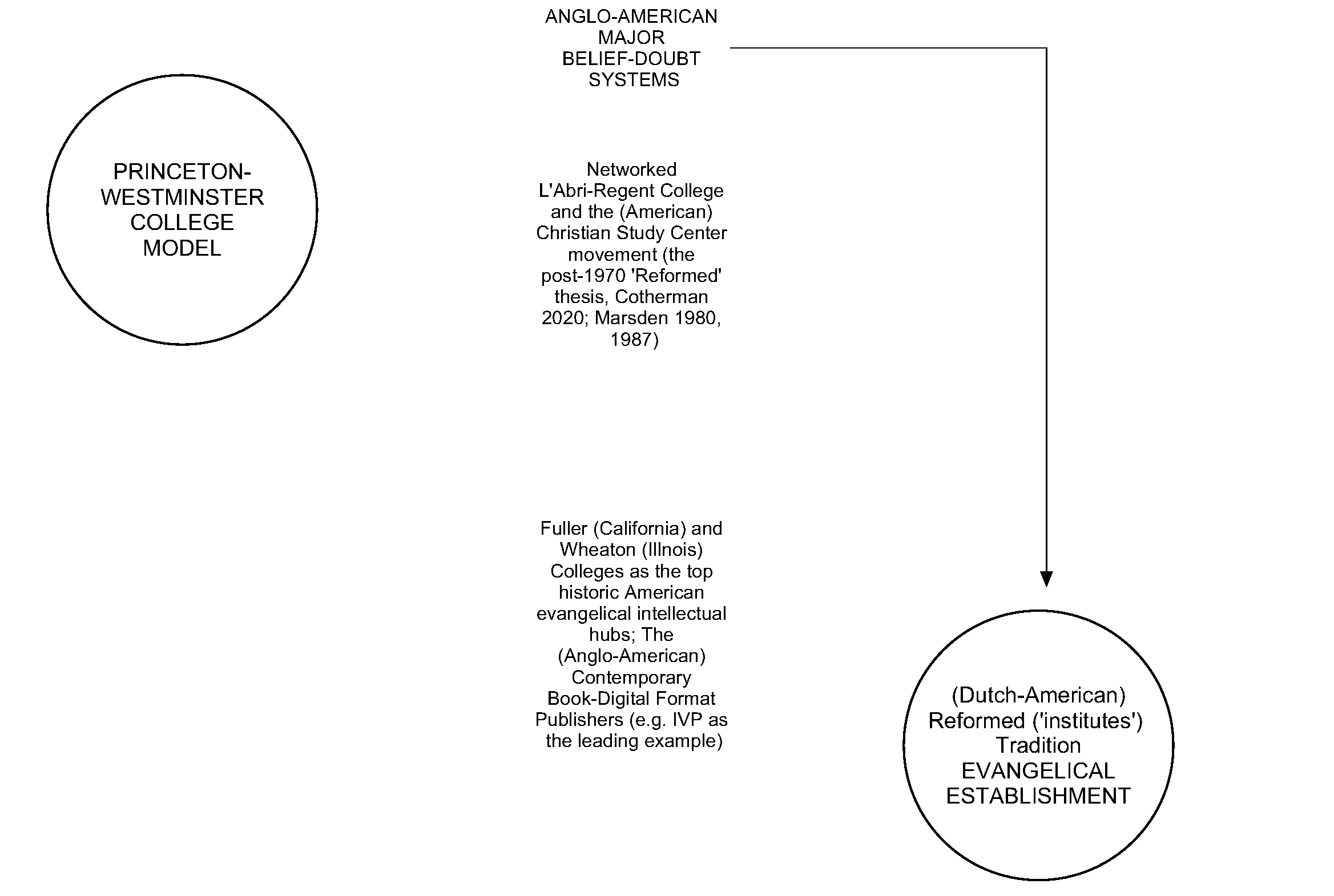

- The (Dutch-American) Reformed (‘institutes’) Tradition EVANGELICAL ESTABLISHMENT

- (British) Tory (Party) Tradition. ESTABLISHMENT.

The conservative tradition in the English-speaking world is best expressed by the ‘British Tory Party’: a descriptor for organisations such as the Conservative Party UK or the Conservative Party of Canada. Political organisations do not align perfectly with ideology, so Toryism is like any other social science model, a genealogical method (as in philosophical term of Nietzsche and Foucault), and, as Bernard William describes it, an origin-type fiction, paralleling the concept of myth, which broadly structures out the non-fiction truth (truthfulness propositions); thus, having accuracy but not the logical accuracy of mathematical truth (Truth and Truthfulness: An Essay in Genealogy, 2002). “The Conservative Mind” (Russell Kirk, 1953) appears to continually to trip-over with this misunderstanding of social science, in its rejection of the thought propositions within the outlook of modernity; ironically, the modernist propositions of hard scientific humanism (in the mid-century) led to a neo-conservative outlook to reject the Nietzschean genealogical method since mythology could not be taken as accurate scientifically. This is done in employing the fallacy of cherry-picking details and failing to understand the mythological or constructivist’s point; or to employ another metaphor, chopping down one tree (or even a few) and think that the concept of the forest has been destroyed; or extending the metaphor: being deaf to the forest in chopping down the tree. Starting with the concept of tradition, the new conservatism, particularly Americanised neo-conservatism (William F. Buckley Jr., God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom”, 1951), has ended up in the cognitive trap of scientism. This has meant that “The Conservative Mind” had the incapacity to see its own ideological faults, in terms of the political and social critiques, and, indeed, the overall ideological critique in terms of systems analysis.

The historical criticism (historiography) of Toryism does the best in plain English terms to demonstrate the shortfall in the thinking. Historically seen, retrospective in time, Tories were monarchists, engaged in a high church Anglican religious heritage, and were opposed to the liberalism of the Whig party. The Conservative model was only ‘recently’ changed – mid-century – with is usually described as ‘Neo-Conservativism’ – the works of Kirk and Buckley Jr., as well as Daniel Bell, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and Irving Kristol. There is then a disjunction between Toryism and the new conservative model, with neo-conservative writers strangely disparaging modern liberal thinkers of having Tory attitudes; in the same twisted logic of Buckley Jr., in accusing academics of having “supernaturalism”. In terms of critical thinking, it does not take much logical understanding to see that the new conservativism is an argument made of fallacious thinking, and is historically a replay of the ancient Roman “language game” of rhetoric to bewilder the public in accepting the false arguments of the modern industrial/post-industrial “The Power Elite” (C. Wright Mills, 1956).

The Oxford College Model is based on the Oxford University Commissioners’ Report of 1852: “The education imparted at Oxford was not such as to conduce to the advancement in life of many persons, except those intended for the ministry.” It is a model of the power elite in the way that the liberal sociologist C. Wright Mills (1956) described it in the American mid-century. Historically, the Oxford College Model has been tied to the Torys’ high church Anglican religious heritage. The link here with the Evangelical world is ambiguous but the intellectual thread is connected in what was called the “Clapham Cabinet” or ‘Sect’ and the history of the Bible Society (‘EHA’ thesis, Piggin & Linder 2018; Lake 2018). The Clapham Sect (technically not a sect but as much part of the established Church of England), or Clapham Saints, were a group of social reformers associated with Clapham in the period from the 1780s to the 1840s. Stuart Piggin & Rob Linder (2018) use the term, Clapham Cabinet, which was made up of its organisational leadership, across Oxbridge and the London Anglican base. The reformers were partly composed of members from St Edmund Hall, Oxford and Magdalene College, Cambridge, where the Vicar of Holy Trinity Church, Charles Simeon had preached to students from the university, and were encouraged by Beilby Porteus, the Bishop of London, himself an abolitionist and reformer, who sympathised with many of their aims. The British and Foreign Bible Society and the Church Missionary Society were associated with the reformers. The Bishop of Oxford in this period (1816-1827) was Edward Legge, Warden of All Souls College, Oxford, from 1817. Catholic emancipation was a long road with strong Puritan and Evangelical opposition, with the markers of the Papists Act 1778, the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1791, the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1793, the removal of the Sacramental Test Act in 1828, and the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, followed by “the Tithe War” of the 1830s (the last of legal anti-Catholic discriminations were not removed until the 1920s). In a three-way political competition, the Anglo-Catholic Bishops and Evangelical reformers, stood together in opposition to any appeasement to Roman Catholics; in the same way, in the mid-century Cold War, that American fundamentalists stood together with American neo-conservatives in opposition to any appeasement to global socialists (and in the ideological language of the Americans, “communist”).

The ambiguity, part from cross-institutional connections, was also that the Claphamites, from about the 1830s, often exemplified Nonconformist conscience with many ended up as the Methodists and the Plymouth Brethren thinkers in a broader socio-political movement against Catholic emancipation. The bigot attitude was part and parcel of the growth of evangelical Christian revivalism in England, which had direct links through Anglo-American revivalists, particularly in the American colonial experience of John Wesley, to the American Revivalist Tradition (ART; Buch 1995). Intellectually, at the time, Evangelical Protestant thought necessitated a conspiratorial evaluation of Catholic thought, aided in the growth of American nationalistic thinking. The liberal historiographical critique of mid-century to late century, among the Anglo-American historians, have developed this critique of ART (including Neo-Evangelical scholars). Yet otherwise excelling Evangelical historians continue to “paper over” the intellectual problem – the too high emphasis on doctrine and inability to conceive the ‘dogma’ problem fully in these histories of evangelicalism. It has to be noted that younger “neo-evangelical” scholars, and older scholars in the field are driving the critique (such as the author, Buch, Lucas, 3:1, June 2023, and forthcoming).

The Oxford College Model is historically linked to English Conservativism because of the university’s role during the English Civil War (1642–1649), as the centre of the Royalist party. From the beginnings of the Church of England as the established church until 1866, membership of the church was a requirement to receive an Oxford BA degree from the university and Protestant dissenter were only permitted to receive the Oxford MA in 1871. In contrast, historically, Cambridge University, has been closely associated to radical thought, although the intellectual history is (again) ambiguous. The history of Cambridge is well-associated with several important “anti-establishment” thinkers or mavericks to conventional thought: Isaac Newton, Francis Bacon, Oliver Cromwell, John Milton, Lord Byron, Charles Darwin, Vladimir Nabokov, John Maynard Keynes, Jawaharlal Nehru, Bertrand Russell, Alan Turing, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Stephen Hawking. It is a far-too simple, and thus false, to set up an Oxford and Cambridge University Model comparison, but if main collegial networks are the truthful point as several important references to the ‘Oxford School’ or the ‘Cambridge School’, the modelling holds (Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change, 1998). Outside of the intellectual history, what made Cambridge distinct, in the terms social organisational history, was the Cambridge Apostles, founded in 1820. Stephen Toulmin, the philosopher of thinking in this research, was a member, so was Alfred Tennyson, Bertrand Russell, G. E. Moore, and John Maynard Keynes. The Soviet spies Anthony Blunt, Guy Burgess and John Cairncross, three of the Cambridge Five, and Michael Straight were all members of the Apostles in the early 1930s, which would also explain intellectual tensions that had existed with the Oxford establishment.

In the Studies-in-Religion field, there is a strong Cambridge-Birmingham-Lancaster network (English north-west direction) with Ninian Smart, John Hick, and Don Cupitt. The Oxford-Cambridge distinction, however, is even stronger in historiography. Historically, a major network thread in the “Oxford School” has been the conservative ‘Great Man’ tradition, originated in the multi-volume Dictionary of National Biography (which originated in 1882 and issued updates into the 1970s); it continues to this day in the new Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. On the other hand, there is a significant connection between radical thought and the “Cambridge School” of historians. Again, this is ambiguous truthfulness (not straightforward): at Oxford, Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton (though, moved to Birmingham) but at Cambridge, G. M. Trevelyan, E. P. Thompson, and Eric Hobsbawm. Other places and centres of English radical thought was much closer to Cambridge than Oxford: Dona Torr at University College London and John Saville at Hull University. The work of the American Peter Novick’s, That noble dream: The ‘objectivity question’ and the American historical profession (1988) was published by Cambridge University Press, and can be contrast to the anti-communist liberal historiography of Oxford’s Isaiah Berlin. Indeed, the strength of Berlin’s history of ideas approach was the benefits in “the Oxford idealism”, a much more clearcut set of critiques of ideas in the Continental tradition, which is seen as too highbrow by social historians in the English radical tradition. These historians of a Cambridge bent were not adverse to systems thought but their ideological criticism rode on a perceived social realism from the social historical context in history-from-below. The Cambridge History of Latin America is eleven volume treatment which is much more honest and open to criticisms on Spanish, Portuguese, English Colonialism.

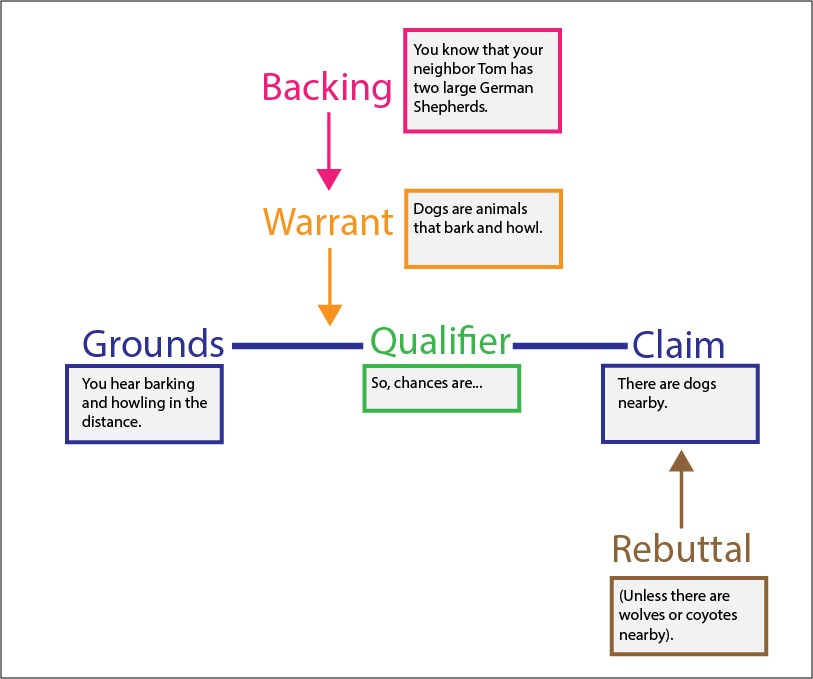

Other fields also reflected in this approach to more contextual and informal logical modes of thought. Stephen Toulmin developed his basic argument of informal logic at Cambridge: the dissertation as An Examination of the Place of Reason in Ethics (1950), where he was influenced by contact with Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose examination of the relationship between the uses and the meanings of language shaped much of Toulmin’s own work. The Toulmin model of argumentation is a diagrammatic six interrelated components used for analysing arguments (The Uses of Argument 1958), and led to “the good reasons approach” a meta-ethical theory that ethical conduct is justified if the actor has good reasons for that conduct, developed in the thinking of Stephen Toulmin, Jon Wheatley and Kai Nielsen. The good reasons approach is not opposed to ethical theory per se, but is antithetical to wholesale justifications of morality and stresses that our moral conduct requires no further ontological or other foundation beyond concrete justifications. The thinking was brought to Oxford when Toulmin was appointed University Lecturer in Philosophy of Science at Oxford University (1949-1954). Toulmin also brought the thinking to Australia when he was Visiting Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Melbourne (1954-1955). The English modern social and theoretical science has a stronger association with Cambridge.

The Toulmin model of argumentation

There are also important economic developments associated with the paradigm of Anglo-American conservative thought, but there is very little distinction between universities, except for the London School of Economics. The economic thinking coming out of Oxford is seen as conservative or conventional, but that is due to the comparison to the history of the London School, which has always been “radical” in both Left and Right semantics. Indeed, while Oxford desires an overall stable historiography (“conventional wisdom”), London expresses the seesawing between 19th century Free-Market Capitalism (Right), Keynesian “Middle-of-the-Road” Regulation (Left), and Neoliberalism (Right). These cognitive risings and falls take place over decades. The neo-liberal thinking as theoretical works came into being during the 1970s. The Adam Smith Institute, a United Kingdom–based free-market think tank and lobbying group that formed in 1977, was a major driver of the neoliberal reforms. The 1980s saw Thatcherism and Reaganism. Then the economic thinking could not be divorced from shifts in international development theory and trade interest from theorists in the United States. In the 1990s there was the neo-liberal politics of Alberto Fujimori in Peru, and the North American Free Trade Agreement. In the culture-history war since the collapse of communist states (1989-1993), the neoliberal turn was much more about the ideological attack of the neo-conservatives upon the social thinking of mid-century liberals like Walter Reuther or John Kenneth Galbraith or Arthur Schlesinger, than the statistical obscure economic models. The Oxford Institute for Economic Policy was founded (2004), and has been for the last 20 years an independent and non-profit think tank focused on analysis, discussion and dissemination of economic policy issues. However, globally it is still unclear what new economic vision will emerge, but it will, and the historiographical spiral will turn Left in a new way. Unfortunately, the social damage has been done, most significantly in the creation of “The (British) Contemporary Higher Education Corporations”. The damage is significant because a common economic complaint, and the new mantra, are the loss of many specific sub-fields of the humanities and social sciences once taught and researched within the universities, creating a skills shortage for global communities, seeking out a new vision. This will be seen in the third section, examining the Cambridge College Model in further details.

- (American) Republican (Party) Tradition. RIGHT POPULISM.

A basic worldview of the Republican Party (United States), founded in 1854, is difficult to sum up as an accurate summative account, but usually read as the ideology of traditional conservativism. The evidence of the ‘shift thesis’ demonstrated that today’s contextual hermeneutics has made this idea of conservatism a false proposition. The ‘shift thesis’ is a widely held view by American historians that the successes of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, meant that the Republican Party’s core base shifted to the Southern states (and intellectually, the Post-1950: “Southern Institutes”), and as the Northeastern states increasingly Democratic (and intellectually reflected the outlook of Pre-1950: “Northern Institutes”). The Republican Party has become the party of right-wing social reaction.

There are several “Southern Institutes” which could be mentioned as closer to the Republican Party, however, because of Buckley Jr.’s 1951 thesis (God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom), universities are marginalised in Republican discussions. Republicans have either attacked the university sector of higher education, or created a new college sector which reflected the traditional conservative curriculum, and often called, “Christian”. In the social reality, but as most cases, these colleges are not ‘traditional conservative’ but the powerhouse of American neo-conservatism. The analysis has to say, “most cases”, as an increasing number of evangelical college communities are fighting back at the colonialisation of “religion” by the Republican Party. Indeed, the excelling evangelical scholars have been, more than half a century back, critics of “American religion”. The smaller but more powerful colleges for the Party are still thinking in terms of neo-fundamentalism, i.e., centralising every argument on the biblical inerrancies. The challenge is that many good evangelical scholars have yet to realise that the modern evangelical apologetic movements of Bill Bright, Chuck Colson (very politically directed under a theological mask for the contemporary Republican ideology) James Dobson, D. James Kennedy, C. Everett Koop, Francis Schaffer, and R.C. Sproul, are eroding the Neo-Evangelical movement in the uncreditable, invalid, and unsound biblical inerrancy claims.

In the middle of this mess of the American South is the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC; the neo-conservative thesis, Miller 1958, Smith 1965, Marty 1970, Handy 1977, Szasz 1982, Buch 1995). I have already explained the role of the SBC in the American neo-conservative thinking in previous publications, but to again recap: Sydney Alhstrom sees anti-intellectualism as a corollary of American revivalism in A Religious History of the American People (1972), and recounted that large elements of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), in their opposition to higher education, worked havoc in the academic program of Southern Theological Seminary in Kentucky. The SBC has had a history of forcing academics out of their seminary positions, often due to academics critical study of the scriptures and Church history. It was under these circumstances that Dr. Crawford Howell Toy was pressured to resign from Southern Baptist Seminary in 1879. Martin Marty (1970) saw Toy’s downfall as a pattern that is typical of southern churches. William H. Whitsett, professor of Church History, also at Southern, had the same fate as Toy nineteen years later (1898). When Whitsett condemned the populist Landmark theory, sectarian Baptists, for whom Landmarkism was a sacred doctrine, threatened to withdraw financial support for the seminary.

Such interference in the academic standards of Southern Baptist seminaries has also been evident in the post-1945 period. In 1962, Professor Ralph H. Elliot was dismissed from his position at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary when his published book, The Message of Genesis (1962), was deemed ‘liberal’. It is important to note that anti-intellectualism does not pervade all areas of the American Revivalist tradition (ART), but is only a common characteristic of the majority which articulate American revivalism. In the case of Neo-Calvinist and Neo-Evangelical scholarship, it is not a matter of anti-intellectualism, but a matter of pseudo-intellectualism, flawed or out-dated scholarship which continues to avoid relevant contemporary criticism of its assumptions. This is why otherwise many good evangelical scholars are blind-sighted to the intellectual problems in their midst, and what the contemporised Republican Party represents. Much of that comes from a vehement anti-liberal populism. The history of the Convention has only pushed further in this direction in recent years.

Apart from the Republican Party and the Southern Baptist Convention and likeminded colleges, it is difficult to say what educational entities are that generates the worldview in a singular institute or school of thought. This is due, as indicated, that the anti-liberal populism is also anti-intellectual and anti-education in the full understanding of the concept of education. One of the important historical marker as an institutional shaper is “The (American federal) Senate’s Southern Caucus (1964)” in a fight against “Civil Rights” being legislated. The type of thinking has been carried through into the new century with the Tea Party movement (2009) and the House Freedom Caucus (2015), and developing into the ideology of Trumpism (2016-).

There is a link here between the contemporised information technology thinking in relation to social visions of the future, cemented into the mythology of the American Dream, or in cynical disappointment, creating its dystopian mirror vision. These are the conversations and rhetoric of the “The (American) Contemporary Informational and Data Corporations”. There are only a few works which makes the linkages clear, historically Jacques Ellul (1964): the original and formative in a strange but effective Neo-Calvinist and Reformed-Marxist mixture of thought. Nevertheless, the cyber-capitalism is well documented, even if few works described the intellectual relationships with concepts of culture, history and nations.

- (British) Radical (Party) Tradition. HOLISTIC DISSENT Dissonance.

English Radicalism or “classical radicalism” or “radical liberalism” had its earliest beginnings during the English Civil War with the Levellers and later with the Radical Whigs, as the retrospective reading of the history in and around the English Civil War. From that development we have, not merely an outdated Whiggish historiography of the 19th century, but the emergence of the new 20th century Progressivist historiography. The new framework is currently evolving in the Postmodern phase. It is not a tradition which will disappear, since philosophically, we can say that somethings are better than others, and since policy says we should not make the better an enemy of the perfect, but the demand for ideological purity is the enemy of social improvement. Hence English Radicalism, or radical parties have been sociologically negative: against the purity of social conservatism, arguing for taking on risks for social change, in the way conservatives continually resist social change to the point of zero (ideologically purity). It is thus ironical that conservatives, still today, accuse the reformist Left of being ‘ideological’. Certainly ‘radicals’ are “ideological” in different variants of: liberalism, republicanism, modernism, secular humanism, antimilitarism, civic nationalism, abolition of titles, rationalism, secularism, redistribution of property, freedom of the press, ‘left-wing causes’, and etc. The ongoing agendas of reforms is what the conservative negatively charge as “being political” with the presumption that most areas of life are generally, on principle, “pre-political”. This is the cause in Conservative blind-side to their own locked-in ideological thinking. Nevertheless, Anglo-American radicalism has its own blind-side.

When conservatives tend to be highly logical in their intellectualism (bubble thinking of logicism), radicals suffer from what I describe as “ Holistic Dissent Dissonance”. The problem is not in taking a holistic approach per se. Nor is the problem in dissenting from convention, or even dissenting from the school of perennial philosophy. It is that there is too frequently cognitive dissonance in the way the poorer radical scholars articulate a positioning of equalitarian holism or any other positioning of radical dissent. Leon Festinger proposed that human beings strive for internal psychological consistency to function mentally in the real world, from his works, When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group That Predicted the Destruction of the World (1956) and A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (1957). Festinger goes on to say that a person experiences internal inconsistency tends to become psychologically uncomfortable and is motivated to reduce the cognitive dissonance, this then leads to a person justifying the stressful behaviour, either by adding new parts to the cognition causing the psychological dissonance (rationalization) or by avoiding circumstances and contradictory information likely to increase the magnitude of the cognitive dissonance (confirmation bias). More simply, persons avoid admitting mistakes in their thinking, and either rationalise what is poorly rational or blocks emotions by removing the thinking from the situation (context). Psychological dissonance affects the conservatives – the avoidance of admitting mistakes – by the logicism which is something like rationalising in Aristotelian universal spirals (adding cycles upon cycles Infineum). Radicals do not have the traditional recourse and so, despite its universality, the argumentations became fragmented and only signal holism without substantiation. For conservative and radical thinker, none of this is pre-determined, and the solution is the model of communicative rationality (Jürgen Habermas, Communication and the Evolution of society, 1979). In its post-metaphysical model, the argument is:

- called into question the substantive conceptions of rationality (e.g., “a rational person thinks this”) and put forward procedural or formal conceptions instead (e.g., “a rational person thinks like this”);

- replaced foundationalism with fallibilism with regard to valid knowledge and how it may be achieved;

- cast doubt on the idea that reason should be conceived abstractly beyond history and the complexities of social life, and have contextualized or situated reason in actual historical practices;

- replaced a focus on individual structures of consciousness with a concern for pragmatic structures of language and action as part of the contextualization of reason; and

- given up philosophy’s traditional fixation on theoretical truth and the representational functions of language, to the extent that they also recognize the moral and expressive functions of language as part of the contextualization of reason.

The model comes out of post-1945 German radicalism, as the school of Critical Theory. Which is to say that the Anglo-American belief systems of radical and conservative thought could fairly engage, even overlap, before 1945, but after 1945 there was a great disjunction, and this uncoincidentally coincided with the bitter reaction of American neo-conservatism.

It explains the disjunction in the Evangelical World. The European influence in the American Neo-Evangelical movement was to fallibilism from the Barthian reading of Kant. This is directly opposed to the positioning of the American (neo-) fundamentalist movement linked into the American neo-conservatist’s ideological purity (e.g., the purity of Americanism and biblical inerrancy).

The Cambridge College Model has been described above as the contrast with the Oxford Model, however, it might be further suggested that Cambridge had more significant ties to Continental Philosophy than Oxford. That is seen in a Cambridge thinker like Wittgenstein, however, Bernard Williams is better to be said to be an Oxbridge thinker, the philosopher who overcame useless divide between the Anglo-American analytic tradition and the European continental tradition. Williams was able to do that by making links between the Cambridge Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language and Frankfurt Habermas’ philosophy of language, all in a deep historiography influenced by Oxford Berlin’s history of continental ideas.

In the Anglo-American evangelical world, the role of the Cambridge Inter-Collegiate Christian Union provided something of the radical influences from both Anglo-American and German thinking. In the former is the Protestant dissenter’s Arminianism, the Reform’s opposition to the deterministic and highly-doctrinaire classic Calvinism. The latter is more British with the links of Hegelian idealism in liberal evangelicalism, before the American variant of Neo-Orthodoxy killed it, for the United States, from its anti-liberal biases. In the Australian evangelical variant, Piggin & Linder tied the Cambridge outlook to the Keswick movement and the suspicion towards doctrinal fundamentalism in the ranks (2018: 449, 501; 2020: 304). Here is the same link to Protestant dissenter’s Arminianism. I refer this historical description as the Sydney Anglican or Moore College’s thesis. It is a fair institutional self-criticism in the history, particularly as the “Sydney Anglican” historical phenomena. Nevertheless, it misses the deeper layer of the intellectual history, particularly framed in Critical Theory.

The historical debates go to what was sustainable in the intellectual framing. On a wider canvas, ‘secular’ (?), we can look at the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (1989). It has been for thirty years examining the same intellectual questions for high-end businesses and technology corporations. (https://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/). Hence, there is a wider ‘secular’ framework in “The (British) Contemporary Ideas and Consultancy Industries”.

- (American) Democrat (Party) Tradition. LEFT POPULISM.

Many of the descriptions of the American Democrat (Party) tradition and American radicalism are the same as described above for English radicalism. There are important differences. As in the ‘shift thesis’ for the Republican Party, the Democrat Party was not in the camp of “social justice” until the late twentieth century, Kennedy-Johnston politics. Democrat Party has to be remembered as the party of carpetbaggers of the 19th century. Something of the legacy lingers in the Party room. Neither can populist American radicalism escape charges of cognitive dissonance, the same cases of English Radicalism. Historian Gordon S. Wood articulated the differences for American Left Populism and Establishment Democrats from their English counterparts in the 1993 Pulitzer Prize book, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (Vintage Books). The American revolution was a completely different to the English Civil War, and has some, but not all, overlap in the concept of a Puritan Revolution. Wood argues that the American colonists appropriated Whig absolute ideals of ‘liberty,’ different to the articulations of the English Civil War. The American variant ultimately came to represent the unity of personal liberty and public liberty, and a residue of representation in a ‘natural aristocracy’. Differences are drawn out by writers like Henry James. The difference is subtle but go to a power play on informal (America) and formal (British) characteristics.

Most significant, is that these differences are moral characteristics. The question is who was more respectable? The practical informality of the Americans, which the British saw as coarse (disrespectful), or the ancient formality of the British, which the Americans saw as hypocrisy (disrespectful). The question arose from the emergence of the Harvard College Model. Daniel Walker Howe (1970) articulated the tradition of Harvard Moral Philosophy in connection to the Unitarian ‘revolution’ at Harvard (The Unitarian Conscience, Harvard University Press). That ‘revolution’ of thought is the rejection of orthodoxy and dogma for informal logic, or as said today, critical thinking. This kind of thinking was reflected in the short-lived Harvard Institute for International Development (1974-2000). Liberal organisations have been plagued on the American scene from anti-liberal biases which arises from the culture(s).

This is what we have today in the crisis of Americanised evangelicalism. ‘The battle of bible’ of the 1970s and 1980s was only the shaper end, theologically, of intellectual framings, which goes to, one side, outside of traditional evangelicalism, Unitarian-Universalist Thought, and the other side, a hard-driven Calvinistic (neo) fundamentalist thinking, all within the United States. This research began as the doctorate of the current author (‘ART’ thesis, Buch 1995). The current crisis of evangelicalism extends back in a history to the 1960s, and also back to the American neo-conservative paradigm of the Cold War 1950s. There are three ART groupings (American Revivalist Tradition, Buch 1995). American revivalism is expressed by the three distinct characteristics of the American Revivalist tradition; biblicalism, anti-intellectualism, and mechanisation of the Christian faith. Biblicalism is the ideology which gives the biblical canon an exalted authority over the life of the believer.

All aspects of belief, doctrine, thought is expected to conform to precepts that biblicalists claim are recorded and supported by the 66 books of scripture. Biblicalism is based on the belief that the whole biblical canon is a harmonious revelation of God, the Word of God. Although most biblicalists would claim that there are areas of scripture that are vague in their meaning and may be given differing interpretations, the fact that the biblicalists make themselves the interpreters of the divine Word of God means biblicalism, like all sacred book traditions, ends up being the tyranny of the believers over themselves. The believer is locked into a cyclical existence where belief is said to come from the Word of God which is itself the belief of the believer. In such an existence, the process of hermeneutics is avoided.

Anti-intellectualism is the second characteristic present in the American Revivalist tradition. Anti-intellectualism is a state of mind which suspects complex and abstract concepts in favour of dogmatic and poorly-constructed beliefs. It has generally involved the slander, censorship, or prohibition of certain academics and their writings. Richard Hofstadter identifies anti-intellectualism as a significant part of the American culture in Anti-intellectualism in American Life (1966). American anti-intellectualism frequently appeared through the use of American apocryphal stories which were recorded in denominational periodicals, as well as the over-the-top criticism of non-evangelical paradigms in literature (usually paperbacks, tapes, and then digital podcasts) of the Apologetics Industry.

Mechanisation of the Christian faith is the third characteristic of the American Revivalist tradition. The American Revivalist tradition sought to implement various techniques to bring about a ‘revival’, and in the process, reduced the Christian life to a series of techniques in evangelism and discipleship. In this way, the Christian faith was merely mechanical, the elements of faith (belief, prayer, worship, etc.) all locked into a machine-like plan. In the post-1945 period, American revivalism became consumed by searching out revivalistic techniques in the form of evangelistic methodologies. There were many American evangelical writers who claim to have discovered the “techniques” that Jesus used with his disciples. To understand the technological nature of the American Revivalist tradition, one needs to turn to the sociological works of Jacques Ellul, Professor of History and Sociology of Institutions at the University of Bordeaux, and a European evangelical in the Calvinist tradition. Ellul formed the thesis that the predominant characteristic of the contemporary human condition is, in the French definition of the word, technique. Technique, once a tool developed for science, is now a mindset that dominates the affairs of humanity; a mindset where the question of “How it works” becomes all important while the question of “Why it is so” becomes increasingly irrelevant. Method is valued more than content.

In the 21st century, then, “The (American Evangelical/Pentecostal) Contemporary Megachurch Incorporations” has become the expression of the paradigm. The current research analysis is based on a large volume of American liberal historiography during the twentieth century, hovering between the consensus and conflictual schools, with a focus on Richard Hofstadter (1963, 1965). It demonstrates that a megachurch can only exist as a business organisation, with membership growth as the prime reason for that existence.

That the megachurch problem is sourced in the history of the American culture, and some might disagree, having described the Australian Pentecostalism as indigenous. The ‘indigenous’ view is supported by Rocha & Hutchinson (2020: 3-4; 2002: 26), Barry Chant (1999: 39), Byron Klaus (Klaus in Dempster, Klaus & Petersen 1999: 127), and Philip Hughes (1996: 3). It is posited that Australian Pentecostalism is local rather than sourced from overseas missions. However, the American history described and explained the phenomenon of the global megachurch. In Australia, the local megachurch phenomena of the 1970s and 1980s were a product of the American revivalist tradition (Buch 1994). The tradition is a historical series of parochial mass movements which shaped the American ideological narrative, and then exported as Americanism (as in American modernism). Mark Hutchinson and John Wolffe (2012) attempt to link the new direction of the ‘indigenous’ view in the era of 1870-1914 with what they describe as a ‘New Global Spiritual Unity’. There is some bearing here, but it is more accurate to say that it was a vision of world mission undergirded by western cultural values rather than being a true vision of global unity. That new vision had to wait for the mid-twentieth century sociology revolution. Sam Hey’s recent works (2011, 2016) has greatly helped to understand the Australian experience of megachurch in the sociologies of Peter L. Berger (1973), Rodney Stark and William S. Bainbridge (1987), Robert Wuthnow (1988), Wade C. Roof (1999), and Scott Thumma and Travis Dave (2007). The new sociology of religion has done much to have shaped the understanding of and for the megachurch, which for the large part is American, and framed in the American culture.

- (English) Colonial (‘institutes’) Tradition. MISSION AND APOLOGETICS.

In popular fiction – novels, television, films – the landscape of London is the signifier of colonialism. This is true as references to “London Institutes”. The “London Missionary Society” (the traditional Protestant mission thesis, Piggin & Linder 2018: 107-15) is at the top of the list. Piggin and Linder refer to the ‘triumphalist spirit of the missionaries’ (110). The ‘religious’ adjoins to the ‘secular’ in City and Guilds of London Institute (Imperial College, 1878). The Institute is an educational organisation in the United Kingdom. Founded on 11 November 1878 by the City of London and 16 livery companies – to develop a national system of technical education, the institute has been operating under royal charter (RC117), granted by Queen Victoria, since 1900. Today, one of it main historical functions is as a registered charity, thereby funding itself as the awarding body for City & Guilds and ILM qualifications, offering many accredited qualifications mapped onto the Regulated Qualifications Framework (RQF).

Here is another great social problem of our times, “The (Anglo-American) Contemporary Public Relations Businesses”. The world of charities and higher education have succumbed to the great mistakes of public relations thinking: 1) dumbing down the narrative of a singular message, 2) engage criticism as unintelligent Apologetics, the system of defence by diverting criticism into fallacious propositions, and 3) produce neo-colonial arguments:

1.0. The Dumbing Down Thesis is well-established, and yet there are ‘religious’ and secular’ readers who act as if it is a surprising new thesis. However, the literature is volumes and sharper to the accurate point than the dismissive institutional apologetics:

1.A. On higher education there is Kenneth Minogue, emeritus professor in political science at the London School of Economics, Alan Smithers, professor of education at Liverpool University, and Frank Furedi, writer and sociologist at the University of Kent, Canterbury (Where Have All The Intellectuals Gone? Continuum, 2004);

1.B. On Secondary Schooling: John Taylor Gatto’s Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling (1991, 2002), where for 30 years there has been nothing new in the criticism of the conventional institutional outlook:

-

-

- It confuses the students. It presents an incoherent ensemble of information that the child needs to memorize to stay in school. Apart from the tests and trials, this programming is similar to the television; it fills almost all the ‘free’ time of children. One sees and hears something, only to forget it again.

- It teaches them to accept their class affiliation.

- It makes them indifferent.

- It makes them emotionally dependent.

- It makes them intellectually dependent.

- It teaches them a kind of self-confidence that requires constant confirmation by experts (provisional self-esteem).

- It makes it clear to them that they cannot hide because they are always supervised.

-

1.C. The Sociology from Below: in the well-known sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s (1930–2002) book, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (1979), proposed that, in a society in which the cultural practices of the ruling class are rendered and established as the legitimate culture, said distinction then devalues the cultural capital of the subordinate middle- and working- classes, and thus limits their social mobility within their own society.

1.D. Sociology from Above: the social critic Paul Fussell touched on the same themes but speaks of “prole drift” in Class: A Guide Through the American Status System (1983) and focused on them specifically in BAD: or, The Dumbing of America (1991). The difference here is that Fussell’s work can be read as a critique of the ruling class thinking or as the ruling class thinking apologetics: the American neo-conservatism.

2.0. The author has already began a series researched essays on the great problem of unintelligent Apologetics and the Apologetics Industry in our social narratives. The first essay is here: “Why the Disciplines and No Apologetics? Part 1: The Collapse of Schaefferan Apologetics”. In James Fodor’s Unreasonable Faith: How William Lane Craig Overstates the Case for Christianity (Hypatia Press, 2018), Foder shows that many of apologetic arguments are not on historical Christianity per se, but rather presents other related targets for skeptics; arguments which are fallaciously abusive in exclusivist claims for faith. “Christian Apologetic” is nothing more than of a dominion theory, which is a majority thinking of American evangelical believers (i.e., right-wing and where the American left-wing evangelical positioning is the minority), BUT a small fundamentalist minority in the Christian world. To those who label themselves “Neo-Evangelical” and to dismissively disagree with the positioning of others in the argument, the call is to consider the weight of evidence in the critical works against Apologetics, not merely for any ‘religion’, but as a ‘secular’ characteristic of the linguistics , and be open to the suggestion that one may have not understood the story of the “Neo-Evangelical rebellion” from fundamentalist orthodoxy, as shown in the historiography of George Marsden and Mark Noll. The historiography starts the analysis as discipline learning, but it then proceeds into seven other sub-disciplinary areas.

3.0. Neo-Colonial Narratives, which is a reference to the debate of the narrative(s) itself (apologetics) and the criticism of the narrative(s) (critical theory). Neocolonialism is the continuation or reimposition of imperialist rule by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony). Neocolonialism takes the form of economic imperialism, globalization, cultural imperialism and conditional aid to influence or control a developing country instead of the previous colonial methods of direct military control or indirect political control (hegemony). That the roots of City and Guilds of London Institute was in Imperial College (1878) is not coincidence but expresses the correlation between technical forms of education and colonialism. In 1907, Imperial College London was established by royal charter, unifying the Royal College of Science, Royal School of Mines, and City and Guilds of London Institute. Here the ethos of scientism and concept of tékhnē is clear.

- (Dutch-American) Reformed (‘institutes’) Tradition. EVANGELICAL ESTABLISHMENT.

The wider neo-colonial criticism of ‘Anglo-American Major Belief System 5’ goes to the historical heart in the broad and various sub-sets of the Dutch Reformed Tradition (‘6’). However, since Charles Hodge of the Princeton-Westminster College Model, in the 19th century, that Dutch Reformed Tradition was reshaped as American Neo-Colonialism. Since the 1960s, the Dutch-American Reformed Tradition has become the intellectual powerhouse of the American Evangelical Establishment, since the Left-Wing Evangelicalism has had to contend with its own cognitive dissonance. Neo-Calvinism works better as system thought because of its tight logic, but that logicism is the means in the loss of critical thinking. The American Evangelical Establishment is neocolonialism in the evangelical world, but now there is a revolt against American evangelical institutions and politics from the Europeans, Brits, Australians, Pacific Islanders, the Africans (ethnic and national variants), groupings of the Middle East (ethnic and national variants), and Central-South-East Asians (ethnic and national variants). The world has had enough of Americans mistaking their own “national culture” for the economic superpower and its neo-colonial agenda. On the ground in the United-States, and overflowed into Canada, Australia, and New Zealand, this can be documented in the ‘Networked L’Abri-Regent College and the (American) Christian Study Center movement’ (the post-1970 ‘Reformed’ thesis, Cotherman 2020; Marsden 1980, 1987). Added to the network, as the American Evangelical intellectual engines, are Fuller (California) and Wheaton (Illinois) Colleges, as the top historic American evangelical intellectual hubs. Furthermore, the great neo-colonial distributors have been “The (Anglo-American) Contemporary Book-Digital Format Publishers (e.g. IVP as the leading example)”.

Concluding remarks

Recently I had to correct an observation on the ‘disbelieving’ ‘Sunday Assemblies’ movement from an evangelical scholar, linking the observation that the movement declined faster than mainline Christian fellowships in the last five years, and all but disappeared while most evangelical groups at least limp on. There was a misunderstood conclusion of the ‘disbelieving’ movement’s telos, ethos, and mission for non-evangelical organisations. The idea of observing “play church without all that Jesus-talk” is another example of completely misunderstanding the telos, ethos, and mission here. There is a distinction between “Jesus-talk” and “God-talk”. A wide gap in the western intellectual histories since the Reformation. Dominic Erdozain’s (2016) The Soul of Doubt: the religious roots of unbelief from Luther to Marx (Oxford University Press) is an excelled treatment why the evangelical criticism is utterly wrong.

It is another great example that Anglo-American evangelical colleges have dropped the ball very badly in missing and substantive fields of the intellectual histories. But then again, such arrogant evangelical leadership — as with the whole arrogance in the Anglo-American belief systems — rejected systems thought ignorantly in succumbing to the faulty thinking of American pragmatism. What “works” is measured by the frameworks of “ideas” (idealism), but if you fail to scope out sufficiently, the thinking is lost in a smaller bubble. Having read Charles Cotherman’s To Think Christianly (2020) this is very clear to me, comparing the bubble scoping of the Americanised Christian study center movements to wider intellectual frameworks.

The Readings which have Developed The Multi-Thread Worldview(s) of this Researched Multi-Layered Critique

Ahlstrom, Sydney E (1972). A Religious History of the American People, New Haven/London. Yale University Press.

Almond, P. (1983). Wilfred Cantwell Smith as Theologian of Religions. The Harvard Theological Review, 76(3), 335-342. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/1509527

Almond, Philip C. (2016). The devil: a new biography. I.B. Tauris, London

Almond, Philip C. (2018). God : A new biography, I.B. tauris, London

Apter, E. (1997). Out of Character: Camus’s French Algerian Subjects. MLN, 112(4), 499-516. Retrieved May 22, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/3251325

Arcus, M. E. (1980). Value Reasoning: An Approach to Values Education. Family Relations, 29(2), 163–171. https://doi.org/10.2307/584067

Barcan, A. (2007). Whatever Happened to Adult Education? AQ: Australian Quarterly, 79(2), 29-40. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/20638464

Bashford, Alison (2007) World population and Australian land: Demography and sovereignty in the twentieth century, Australian Historical Studies, 38:130, 211-227, DOI: 10.1080/10314610708601243

Beaumont, Joan (2015). Remembering Australia’s First World War, Australian Historical Studies, 46:1, 1-6, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2015.1000803

Berger, Peter L (1973). The Social Reality of Religion, Harmondsworth, Penguin.

Berlin, Isaiah (1958). Two Concepts of Liberty, Lecture, at the University of Oxford on 31 October 1958.

Berlin, Isaiah; with Bernard Williams (1994). ‘Pluralism and Liberalism: A Reply’ (to George Crowder, ‘Pluralism and Liberalism’, Political Studies 42 293–303), Political Studies 42 (1994), 306–9.

Binnion, Denis (1997). What’s New in Course Programming? A Brief Analysis of WEA Course Programs 1917-1976, Australian Journal of Adult and Community Education, 37:1, 27–32.

Binnion, Denis (2013). One Hundred Years of the WEA, Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 53:30, 478–481.

Blackstock, A., & O’Gorman, F. (Eds.). (2014). Loyalism and the Formation of the British World, 1775-1914. Woodbridge, Suffolk, UK; Rochester, NY, USA: Boydell & Brewer. doi:10.7722/j.ctt5vj7dp

Borghesi, Massimo (2021). Catholic Discordance: Neoconservatism vs. the Field Hospital Church of Pope Francis, Collegeville: Liturgical Press Academic

Bosworth, R.J.B. (2011) The Second World Wars and their Clouded Memories, History Australia, 8:3, 75-94, DOI: 10.1080/14490854.2011.11668389

Bourdieu, Pierre (1979). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste, Routledge.

Bourdieu, Pierre (with Jean Claude Passeron, 1990). Reproduction in Education, Society and Culture, London: Sage Publications Ltd.

Bourke, Paul (1976) Politics and ideas: The work of Richard Hofstadter, Historical Studies, 17:67, 210-218, DOI: 10.1080/10314617608595548

Brown, David S. (2006). Richard Hofstadter: An Intellectual Biography, University of Chicago Press.

Bruner, Jerome S. (1977). The Process of Education, Cambridge: Harvard University Press,

Bruner, Jerome S. (1996). The Culture of Education. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Buccola, Nicholas (2019). The Fire is Upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate over Race in America, Princeton University Press.

Buch, Neville (1994). American Influence on Protestantism in Queensland since 1945, Ph.D. thesis, Department of History, University of Queensland, August. (Awarded April 1995)

Buch, Neville (1995). ‘Americanizing Queensland Protestantism’, Studying Australian Christianity 1995 Conference, Robert Menzies College, Macquarie University, July.

Buch, Neville (1995). The Significance of the American Invasion for Australian Churches: A Preliminary Examination, War’s End Conference (Queensland Studies Centre, Griffith University), University Hall, James Cook University, July.

Buch, Neville (1997). ‘‘…many distractions confronting the Church’: The Responses of Protestant Religion to Popular Culture in Queensland 1919-1969,’ Everyday Wonders Popular Culture: Past and Present’, 10th International Conference, Crest Hotel, Brisbane, June.

Buch, Neville (2007). Religion Remain a Problem. The Skeptic. Summer.

Buch, Neville (2017). Hearts Lifted Up with the Spirit of Seton. A History of Seton College, Mount Gravatt East, Queensland, November 2017.

Buch, Neville (2018). Small is Big: Scaling the Map for Brisbane Persons and Institutions 1825-2000. ‘The Scale of History’ AHA Conference, Australian National University, 4 July 2018.

Buch, Neville (2019). The Australian Literary Setting of the ‘Queensland Character’ and Mid-Twentieth Century Philosophy: The Philosophical Development of Jack McKinney and the Problem of Knowledge 1935-1975. Revolutions & Evolutions in Intellectual History Conference. International Society for Intellectual History, University of Queensland, 6 June 2019.

Buckley Jr., William F. (1951). God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom”, Washington, D.C: Regnery Publishing.

Buckley, William F. (1959, 2016). Up From Liberalism, Martino Fine Books

Burns, A. (1962). Australia, Britain, and the Common Market: Some Australian Views. The World Today, 18(4), 152-163. Retrieved May 6, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/40394180

Burns, A. L. S. Encel & D. E. Kennedy (1969) The political sciences: A symposium, Historical Studies, 14:53, 73-79, DOI: 10.1080/10314616908595408

Carr, Helen and Suzannah Lipscomb (edited, 2021). What is History Now? How the Past and Present Speak to Each Other, Weidenfeld & Nicolson, London, UK.

Carter, Sarah (2018) Book Review: Building Better Britains? Settler Societies in the British World 1783–1920, Australian Historical Studies, 49:2, 277-278, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2018.1454269

Carwardine, Richard (1978). Trans-Atlantic Revivalism: Popular Evangelicalism in Britain and America 1790-1865, Connecticut: Greenwood Press.

Chant, Barry (1999), ‘The spirit of Pentecost: Origins and development of the Pentecostal movement in Australia, 1870–1939’, PhD thesis, Macquarie University.

Cherrington, E. (1923). World-Wide Progress toward Prohibition Legislation. The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 109, 208-224. Retrieved April 28, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/1015011

Chomsky, Noam (2004; edited by Donaldo Macedo). Chomsky on Mis-Education, Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield

Collins, Randall (1998). The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change, Harvard University Press.

Collins, Randall (1999). Macrohistory : essays in sociology of the long run. Stanford University Press, Stanford, Calif

Collins, Randall (2005). Interaction ritual chains. Princeton University Press, Princeton, N.J. ; Oxford

Collins, Randall (2008). Violence A Micro-sociological Theory, Princeton University Press

Collins, Randall (2019). The Credential Society: An Historical Sociology of Education and Stratification, Columbia University Press.

Corning, P. (2008). Holistic Darwinism: The New Evolutionary Paradigm and Some Implications for Political Science. Politics and the Life Sciences, 27(1), 22-54. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/40072944

Cotherman, Charles E. (2020). To Think Christianly, IVP Academic

Crawford, John (2019) Book Review: Race and Imperial Defence in the British World, 1870–1914, Australian Historical Studies, 50:3, 394, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2019.1633049

Crawford, R. M. (1945) History as a science, Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand, 3:11, 153-175, DOI: 10.1080/10314614508594856

Crawley, Rhys (2015) Marching to the Beat of an Imperial Drum: Contextualising Australia’s Military Effort During the First World War, Australian Historical Studies, 46:1, 64-80, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2014.994540

Crozier-De Rosa, Sharon (2019) Book Review: You Daughters of Freedom: The Australians Who Won the Vote and Inspired the World, Australian Historical Studies, 50:3, 389-390, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2019.1633042

Cupitt, Don (2008). The Meaning of the West: An Apologia for Secular Christianity, SCM Press

Cupitt, Don (2009). Jesus and Philosophy, SCM Press

Curtis, Jesse (2021). The Myth of Colorblind Christians : Evangelicals and White Supremacy in the Civil Rights Era, New York University Press

Dadswell, Gordon (2005). The Workers’ Educational Association of Victoria and the University of Melbourne: a Clash of Purpose? Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 45:3, 331–351.

Dadswell, Gordon (2007). From Idealism to Realism: the Workers’ Educational Association of Victoria 1920-1941, History of Education Review, 36:2, 61–73.

Davey, Gwenda Beed (2016) Book Review: Children, Childhood and Youth in the British World, Australian Historical Studies, 47:3, 496-498, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2016.1208721

Davis, Michael (2017) Book Review: Climate, Science, and Colonization: Histories from Australia and New Zealand, Australian Historical Studies, 48:1, 125-126, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2016.1273047

de Beauvoir, Simone (1972). All Said and Done: The Autobiography of Simone de Beauvoir 1962-1972, Paragon House.

Dempster, Murray A, Klaus, Byron D & Petersen, Douglas (edited, 1999), The Globalization of Pentecostalism: a religion made to travel, Regnum, Oxford.

De Sousa Santos, B. (1992). A Discourse on the Sciences. Review (Fernand Braudel Center), 15(1), 9-47. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/40241211

Dewey, John (1909). Moral Principles in Education, Boston : Houghton Mifflin

Dewey, John (1916). Democracy and Education: An Introduction to the Philosophy of Education, London: Macmillan and Co. Limited.

Dewey, John (1938). Experience and Education, New York: Simon and Schuster.

Dilthey, Wilhelm; Rudolf A. Makkreel and Frithjof Rosi (2019). Wilhelm Dilthey: Selected Works, Volume VI: Ethical and World-View Philosophy, Princeton University Press

Donnelly, Kevin (edited 2022). Christianity Matters: In These Troubled Times, Melbourne: Wilkerson.

Du Mez, Kristin Kobes (2020). Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation, New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation

Dymock, Darryl (2001). ‘A Special and Distinctive Role’ in Adult Education, WEA Sydney 1953-2000, Allen & Unwin, State Library of NSW Mitchell Library.

Echenberg, M. (2002). Pestis Redux: The Initial Years of the Third Bubonic Plague Pandemic, 1894-1901. Journal of World History,13(2), 429-449. Retrieved May 22, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/20078978

Edwards, Lee (2019). William F. Buckley Jr. : The Maker of a Movement, ISI Books

Elliot, Ralph H. (1962). The Message of Genesis, The Bethany Press

Ellul, Jacques (1964). The Technological Society. Translated from the French by John Wilkinson. With an introd. by Robert K. Merton Knopf New York

Ellul, Jacques (1973). Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes, New York:

Erb, F. (1916). The Development of the Young People’s Movement. The Biblical World, 48(3), 129-192. Retrieved May 6, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/3142079

Erdozain, Dominic (2016). The Soul of Doubt: the religious roots of unbelief from Luther to Marx, Oxford University Press

Fanon, Frantz (1963). The Wretched of the Earth, Penguin, London, UK.

Faye, Esther (1998). Growing up ‘Australian’ in the 1950s: The dream of social science, Australian Historical Studies, 29:111, 344-365, DOI: 10.1080/10314619808596077

Fisher, Helen (2019). Anatomy of Love: A Natural History of Mating, Marriage, and Why We Stray, WW Norton & Co.

Festinger, Leon (1956). When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group That Predicted the Destruction of the World, New York : Harper & Row

Festinger, Leon (1957). A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance, Stanford University

Fodor, James (2018). Unreasonable Faith: How William Lane Craig Overstates the Case for Christianity, Hypatia Press, US.

Frankfurt, Harry G. , Translated by Michael Bischoff (2014). Bullshit, Suhrkamp Verlag AG

Freeman, Mark (2013). ‘An Advanced Type of Democracy’? Governance and Politics in Adult Education C.1918-1930, History of Education, 42:1, 45–69.

Freire, Paulo. (1970a). Cultural Action and Conscientization, Harvard Education Review, 40, (3), 452-477.

Freire, Paulo. (1970b). Pedagogy of the Oppressed, New York: Seabury Press.

Freire, Paulo. (1973). Education for Critical Consciousness, New York: Seabury Press.

Freire, Paulo. (1976). Education, the Practice of Freedom, London: Writers and Readers Publishing Cooperative.

Freire, Paulo. (1985). The Politics of Education: Culture, Power and Liberation, South Hadley: Bergin & Garvey.

Freire, Paulo. (1994). Pedagogy of Hope: Reliving Pedagogy of the Oppressed, New York: Continuum.

Freire, Paulo. (1998b). Politics and Education, Los Angeles: UCLA Latin American Center Publications.

Freundlieb, Dieter & Hudson, Wayne & Rundell, John F (2004). Critical theory After Habermas. Brill, Leiden ; Boston

Friesen, G., & Taksa, L. (1996). Workers’ Education in Australia and Canada: A Comparative Approach to Labour’s Cultural History. Labour History, (71), 170-197. doi:10.2307/27516453

Fukuyama, Francis (2012). The End of History and the Last Man (Twentieth anniversary edition). London Penguin Books

Furedi, Frank (2004). Where Have All The Intellectuals Gone? Continuum

Fussell, Paul (1983). Class: A Guide Through the American Status System, Simon & Schuster

Fussell, Paul (1991). BAD: or, The Dumbing of America, Summit Books

Garrison, J. (1995). Deweyan Pragmatism and the Epistemology of Contemporary Social Constructivism, American Educational Research Journal, 32(4), 716-740.

Gatto, John Taylor (1991, 2002). Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling, New Society Publishers

Gert, B. (2005). Moral Arrogance and Moral Theories. Philosophical Issues, 15, 368–385. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27749850

Giovanni B. Sala & Spoerl, J (1994). Intentionality versus Intuition (pp. 81-101) in Doran R. (Ed.), Lonergan and Kant (pp. 81-101). University of Toronto Press. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/10.3138/j.ctt2tv28t.8

Goldberg, S. C. (2016). Arrogance, Silence, and Silencing. Proceedings of the Aristotelian Society, Supplementary Volumes, 90, 93–112. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26780423

Graham, Elaine (2013). Between a Rock and a Hard Place: Public Theology in a Post-Secular Age, SCM Press

Gray, John. Berlin. Fontana, 1995

Grayling, A.C. (2022). For the Good of the World : Is Global Agreement on Global Challenges Possible? Oneworld Publication

Griffiths, Tom (1989) ‘The natural history of Melbourne’: The culture of nature writing in Victoria, 1880–1945, Australian Historical Studies, 23:93, 339-365, DOI: 10.1080/10314618908595818

Haack, Susan (1993). Evidence and Inquiry: Towards Reconstruction in Epistemology, London: Wiley-Blackwell.

Habermas, Jürgen (1991). Knowledge and Human Interests, Polity Press

Habermas, Jürgen (1991). The Theory of Communicative Action : Lifeworld and Systems, a Critique of Functionalist Reason, Volume 2, Polity Press

Habermas, Jürgen (1997). Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy, Polity Press

Habermas, Jürgen (1992). Communication and the Evolution of Society, Polity Press

Habermas, Jürgen (2010). Legitimation Crisis, Polity Press

Hammonds, E. (2011). Race and the Genetic Revolution: Science, Myth, and Culture (Krimsky S. & Sloan K., Eds.). New York: Columbia University Press. doi:10.7312/krim15696

Handasyde, K. ., & Massam, K. (2022). Introduction to the Special Issue: Dialogues of Secular and Sacred: Christianity in Mid-Twentieth-Century Australian Culture. Journal for the Academic Study of Religion, 35(1), 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1558/jasr.22399

Handy, Robert T. (1976). A History of the Churches in the United States and Canada, Oxford at the Clarendon Press.

Handy, Robert T. (1977). A Christian America: Protestant Hopes and Historical Realities, New York. Oxford University Press.

Hardcastle, V. (1993). The Naturalists versus the Skeptics: The Debate Over a Scientific Understanding of Consciousness. The Journal of Mind and Behavior, 14(1), 27-50. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/43853732

Harris, F. (2007). Dewey’s Concepts of Stability and Precariousness in His Philosophy of Education, Education and Culture, 23(1), 38-54.

Heuer, Ulrike and Gerald Lang (eds., 2012). Luck, Value and Commitment: Themes from the Ethics of Bernard Williams, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hey, Sam (2011). God in the Suburbs and Beyond: The Emergence of an Australian Megachurch and Denomination. Ph.D. thesis, School of Humanities, Griffith University.

Hey, Sam and Geoff Waugh (2016). Megachurches: Origins, Ministry and Prospects. Morning Star Publishing.

Hoffer, Eric (2002). The True Believer : thoughts on the nature of mass movements (First Perennial Modern Classics edition). Harper Perennial Modern Classics, New York

Hoffer, Peter Charles (2014). Clio among the Muses: Essays on History and the Humanities, New York University Press

Hofstadter, Richard (1955, re-issued 1988). The Age of Reform: From Bryan to f.d.r., New York: Random House USA Inc.

Hofstadter, Richard (1963). Anti-intellectualism in American Life, New York: Random House USA Inc.

Hofstadter, Richard (1965; rev. edition, 2008) The Paranoid Style in American Politics, and Other Essays, New York: Random House USA Inc.

Holifield, B. (2010). Who Sees the Lake? Narcissism and Our Relationship to the Natural World. Jung Journal: Culture & Psyche, 4(1), 19-31. doi:10.1525/jung.2010.4.1.19

Hook, Sidney (1971). Illich’s De-Schooled Utopia, Encounter 37 (4), 53-56.

Horne, Donald. (1964; 2009). The Lucky Country, Penguin Random House Australia

Horne, Donald (1976). Death of the Lucky Country, Penguin Books Australia

Horne, Donald (2022). The Education of Young Donald Horne Trilogy, NewSouth Publishing

Howe, Brian & Hughes, Philip, et al. (2003). Spirit of Australia II : religion in citizenship and national life. ATF Press, Hindmarsh, SA

Howe, Charles (1999). Clarence R. Skinner: Prophet of New Universalism, Boston: Skinner House Books

Howe, Charles (2005). The Essential Clarence Skinner: A Brief Introduction to His Life and Writing, Boston: Skinner House Books

Howe, Daniel Walker (1970). The Unitarian Conscience: Harvard moral philosophy, 1805-1861, Harvard University Press

Howe, Neil and William Strauss (2007). Millennials Go to College, LifeCourse Associates

Howe, Renate (1980) Protestantism, social Christianity and the ecology of Melbourne, 1890–1900, Historical Studies, 19:74, 59-73, DOI: 10.1080/10314618008595624

Hudson, Wayne (1997). Constructivism and history teaching. Griffith University, Brisbane, Qld.

Hudson, Wayne (2016). Australian Religious Thought, Monash University Publishing

Hughes, Philip (1996). The Pentecostals in Australia, Australian Government Publishing Service, Canberra, ACT.

Huntington, Samuel (1996). The Clash of Civilizations and the Remaking of World Order, Simon & Schuster.

Hutchinson, Mark & Wolffe, John (2012). A Short History of Global Evangelicalism, New York: Cambridge University Press

Jackman, S. (1994). Measuring Electoral Bias: Australia, 1949-93. British Journal of Political Science, 24(3), 319-357. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/194252

James, Henry (1916, 2004). The Ivory Tower, Introduction by Alan Hollinghurst, Essay by Ezra Pound, New York Review Books.

Jiang, J. (2017). Character and Persuasion in William James. William James Studies, 13(1), 49-70. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/26203815

Kant, Immanuel (1781, 2007). Translated by Marcus Weigelt. Critique of Pure Reason, Penguin Books.

Kohn, Rachael (2003). The New Believers: Re-Imagining God, Harper Collins

Lake, Marilyn (2019). Progressive New World: how settler colonialism and transpacific exchange shaped American reform. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts ; London, England

La Nauze, J. A. (1965) Hearn on natural religion: An unpublished manuscript, Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand, 12:45, 119-122, DOI: 10.1080/10314616508595314

Lake, Marilyn (2013) British world or new world? History Australia, 10:3, 36-50, DOI: 10.1080/14490854.2013.11668478

Lake, Marilyn (2014) Challenging the ‘Slave-Driving Employers’: Understanding Victoria’s 1896 Minimum Wage through a World-History Approach, Australian Historical Studies, 45:1, 87-102, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2013.877501

Lake, Meredith (2018). The Bible in Australia: A cultural history, Sydney: New South.

Law, Stephen (2007). The War for Children’s Minds, London: Routledge.

Leaves, Nigel (2004). Odyssey on the Sea of Faith: The Life & Writings of Don Cupitt, Polebridge Press, Farmington, MN.

Lindvall, T., & Quicke, A. (2011). The Studio Era of Christian Films. In Celluloid Sermons: The Emergence of the Christian Film Industry, 1930-1986 (pp. 116-143). NYU Press. Retrieved May 9, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt9qfkzh.9

Lowenthal, David (1996). The Heritage Crusade and the spoils of history. Viking, London

Lowenthal, David (2015). The Past is a Foreign Country – revisited (Revised and updated edition). Cambridge University Press, Cambridge ; New York

Lowenthal, David (2019). Quest for the Unity of Knowledge. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group, London ; New York

Macintyre, Stuart (2009) The Poor Relation: Establishing the Social Sciences in Australia, 1940–1970, Australian Historical Studies, 40:1, 47-62, DOI: 10.1080/10314610802663019

Ma, W. (2008). Review of Miller & Yarmamori’s Global Pentecostalism in Transformation, 25(4), 274-276. Retrieved May 9, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/43052748

Macklin, Michael (1972). To Deschool Society, Cold Comfort, December 1972.

Macklin, Michael (1975). Those Misconceptions are not Illich’s, Educational Theory, 25 (3), 323-329

Macklin, Michael (1976). When Schools are Gone: A Projection of the Thought of Ivan Illich, St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Macklin, Michael (1986). Education in and for a Multicultural Australia, Australian Teachers Federation Conference, Sydney, October 1986.

Maddox, M. (2003). God, Caesar & Alexander. AQ: Australian Quarterly, 75(5), 4-39. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/20638202

Maddox, M. (2015). Finding God in Global Politics. International Political Science Review / Revue Internationale De Science Politique, 36(2), 185-196. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/24573460

Maddox, Marion (2001). For God and Country: Religious Dynamics in Australian Federal Politics, Canberra: Parliament of Australia

Maddox, Marion (2005). God Under Howard: The Rise of The Religious Right in Australian Politics, Sydney: Allen & Unwin

Maddox, Marion (2014). Taking God to School: The End of Australia’s Egalitarian Education, Allen & Unwin

Magee, Bryan (1997). Confessions of a Philosopher: A Personal Journey through Western Philosophy from Plato to Popper, New York: The Modern Library.

Mander, Jerry (1978, 2002). Four Arguments for the Elimination of Television, HarperCollins.

Mandik, P. (2011). Supervenience and neuroscience. Synthese, 180(3), 443-463. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/41477566

Marsden, George M. (1980). Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth Century Evangelicalism 1870-1925, New York. Oxford University Press.

Marsden, George M. (1987). Reforming Fundamentalism. Fuller Seminary and the New Evangelicalism, Grand Rapids: William B. Eermanns Publishing Company.

Marti, Gerardo (2020). American Blindspot: Race, Class, Religion, and the Trump Presidency, London: Rowman & Littlefield.

Marty, Martin E. (1970). Righteous Empire. The Protestant Experience, New York: The Dial Press.

Martyn Lyons (2010) A New History from Below? The Writing Culture of Ordinary People in Europe, History Australia, 7:3, 59.1-59.9, DOI: 10.2104/ha100059

Massam, K. (2022). ‘All Our Time’: Catechetics, Cardijn and the Jesus of Everyday Discipleship. Journal for the Academic Study of Religion, 35(1), 74–93. https://doi.org/10.1558/jasr.22396

Mays, C. (2013). Who’s Driving This Thing, Anyway?: Emotion and Language in Rhetoric and Neuroscience. JAC, 33(1/2), 301-314. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/43854552

McCutcheon, Russell T & Walter de Gruyter & Co (2018). Fabricating Religion: fanfare for the common e.g. De Gruyter, Berlin ; Boston

McKinney, Jack Philip (1971). The Structure of Modern Thought, London, Catto & Windus.

McLoughlin, William G. (1957). Modern Revivalism: Charles Grandison Finney to Billy Graham, New York. Ronald Press. 1957.

McLoughlin, William G. (1960). Billy Graham: Revivalist in a Secular Age, New York. The Ronald Press Company. 1960.

McLoughlin, William G. (1987). Revivals, Awakenings and Reform: An Essay on Religion and Social Change in America 1607-1977, The University of Chicago Press.

McGilchrist, Iain (2009). The Master and his Emissary: The Divided Brain and the Making of the Western World, Yale University Press

Meyer, Birgit (2005.) Religion, Media, and the Public Sphere, Indiana University Press

Michael Crozier (2002). Society economised: T.R. Ashworth and the history of the social sciences in Australia, Australian Historical Studies, 33:119, 125-142, DOI: 10.1080/10314610208596205

Milana, Marcella, et al. “The Role of Adult Education and Learning Policy in Fostering Societal Sustainability.” International Review of Education, vol. 62, no. 5, 2016, pp. 523–540.

Miller, D. (1943). G. H. Mead’s Conception of “Present”. Philosophy of Science, 10(1), 40-46. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/184881

Miller, Donald E. and Tetsunao Yamamori (2007). Global Pentecostalism: The New Face of Christian Social Engagement, Berkeley: University of California Press.

Miller, J. M., Saunders, K. L., & Farhart, C. E. (2016). Conspiracy Endorsement as Motivated Reasoning: The Moderating Roles of Political Knowledge and Trust. American Journal of Political Science, 60(4), 824–844. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24877458

Miller, Joshua L. (2011). Accented America : the cultural politics of multilingual modernism. Oxford University Press, Oxford ; New York

Miller, Paul D. (2022). The Religion of American Greatness: What’s Wrong With Christian Nationalism, IVP Academic

Miller, R. (1939). Is Temple a Realist? The Journal of Religion,19(1), 44-54. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/1197939

Miller, R. (1985). Ways of Moral Learning. The Philosophical Review, 94(4), 507-556. doi:10.2307/2185245

Miller, Robert M. (1958). American Protestantism and Social Issues 1919-1939, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. 1958.

Miller, Seumas, “Social Institutions”, The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Summer 2019 Edition), Edward N. Zalta (ed.), URL = <https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/sum2019/entries/social-institutions/>.

Morris, Roger K (2013). The WEA in Sydney, 1913 – 2013: Achievements; Controversies; and an Inherent Difficulty, Australian Journal of Adult Learning, 53:3, 487–498.

Mozley, Ann (1964) The history of Australian Science, Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand, 11:42, 258-259, DOI: 10.1080/10314616408595282

Murphy, Patrick D., & Hoffman, Michael J.(1992). Critical essays on American modernism. G.K. Hall ; Toronto : Maxwell Macmillan Canada ; New York : Maxwell Macmillan International, New York

Myers, Benjamin (2012). Christ the Stranger: The Theology of Rowan Williams, t & t Clark.

Nagel, Thomas (1986). The view from nowhere. Oxford University Press, New York

Naugle, David K. (2002). Worldview: The History of a Concept, William B. Eermann Publishing Company

Nelson, Eric S. (2019; edited). Interpreting Dilthey: Critical Essays, Cambridge University Pres