Why the Confusion Over Professional History? Brewer’s Insights on Popular Historiography

Brewer’s Famous Quotations

Introduction

It is very difficult to communicate the art, the discipline, the profession of history to those who never have been immersed in it. There is much confusion about serious reflection on history because the idea of history, in the general mindset, is so conditioned by sound bites and other quotations. There are many books of quotations but Brewer’s Famous Quotations, with extensive annotations on 5,000 popularly referenced quotes, is one of the best, and has been recently produced by Nigel Rees. By delving into this one very large collection, and searching out references to the ‘past’ and to ‘history’, a picture forms to explain popular misconceptions about what history is supposed to do. Except for very few and dispersed history ‘enthusiasts’, people generally do not read books on history. In popular imagination history is conveyed by the novel, the film, or the television drama. Web formatted social media might be a counter-balance with recent popular sites for entertaining-yet-serious short ‘teaching’ videos. With the exception for those who do read extensively, the quip on the subject is about all that most persons can comprehend as history. The quotation is not necessarily false and, from a depositary of further understanding, it might be very insightful. Nevertheless, as the only basis to comprehend the subject it delivers a great misunderstanding on the past and also on the disciplinary effort to frame the past. Popular quotations on history and the past can be clustered together as historiographical threads. Taken together the threads are often contradictory conclusions, and they forgo the effort to dig a little deeper cognitively to get to a comprehensive image or scape. What follows are seven images of history and the past that are found as different threads of popular quotations in the Brewer’s Famous Quotations. Other dictionaries of quotations might bring forth other threads, but it would seem we have here a good start in untangling the confusion on history.

“Son, history is important because it’s the story of our past that we rewrite to understand our present”. Source: CartoonStock Order #282339, cwln3950_hi

History as Mere Notes on the Present

There is the notion that history is merely notes on the present. “News [or journalism] is the first [rough] draft of history”, was allegedly first said by Philip Graham in The Washington Post (24 November 1985) and has been a frequent quip of the media ever since. It might seem that the quote is about the nature of journalism but its meaning is a commentary on history. This view that history arises from the present, a latter version of current affairs and media outputs, is called ‘Presentism’. The historiography, or rather, anti-historiography was empathetically challenged by Lynn Hunt as President of the American Historical Association in May 2002:

…In this, they [history students] reflect the interests of the general public, which often resents the scholarly insistence on revealing all the foibles of past men and women. They don’t always want history to teach them the inadequacies of people in the past or even to reassure them about their own identities in the present. It’s the difference of the past that renders it a proper subject for epic, romance, or tragedy-genres preferred by many readers and students of history. The “ironic” mode of much professional history writing just leaves them cold.

Presentism admits of no ready solution; it turns out to be very difficult to exit from modernity or our modern Western historical consciousness. But it is possible to remind ourselves of the virtues of maintaining a fruitful tension between present concerns and respect for the past. Both are essential ingredients in good history…

Although affirming its appeal, the danger for Hunt was that “Presentism, at its worst, encourages a kind of moral complacency and self-congratulation”. It is a criticism that resides at the back of the quotation from Jawaharial Nehru: “History is almost always written by the victors and conquerors and gives their viewpoint.” It is similar to the ‘Zimbabwean proverb’: “Until lions have their own historians, history will always glorify the hunter.” One has to be careful that a critical view does not end up reinforcing the presentist’s misunderstanding of history. It should be acknowledged that the discipline has taken a hold of many non-western perspectives and non-traditionalist frameworks; even if not all practitioners are consistent to the cosmopolitan ideal. If the argument of presentism were true then histories of colonialism, racism, cultural pluralism (cosmopolitanism), and of national and cultural independence in the ‘third world’, would not be possible.

“Change, change, change – all we ever seem to get is change! Source: CartoonStock Order #282339, rben110_hi

Ideas of the Past… people doing history unawares

The upside is that most persons have an idea of the past and in reflecting on that idea of the past, mostly unawares; we are all doing history in a primal sense. “Life must be lived forwards, but it can only be understood backwards,” said Soren Kierkegaard. It is a two-part idea that is well encapsulated in the statement by the English playwright John Osborne in his play, Look Back in Anger (Act 2. Sc. 1, 1956): “They spend their time mostly looking forward to the past”. It is said that the American artist, Charles Demuth, when asked in 1929, ‘What do you look forward to?’ remarked, ‘The past’. ‘Looking Forward to the Past’ was the title of a history chat show on BBC Radio 4 in the 1990s. Our vision of the future is embedded in how we view the past, or it is for some persons, and/or some of time. The opposite is also true. When historians look at the fields of futurism (a rejection of the past for the modern art) or futurology (future studies from the past) there is a clear disjunction between our real past and real future. “The past is a foreign country: they do things differently there”, stated L.R. Hartley in his novel, The Go-Between (1953). Between Osborne’s play and Hartley’s novel, both composed in the 1950s Britain milieu, there are a host of historical themes which highlight the disjunction. In Look Back in Anger there is the disillusionment and rejection of traditional British society. Osborne and Kingsley Amis and other working and middle class British playwrights and novelists of the era became associated with the phrase, “angry young men”, and these were those “impatience with the status quo, refusal to be co-opted by a bankrupt society, an instinctive solidarity with the lower classes.” It contrasts strongly with the themes of nostalgia and childhood memory in The Go-Between. It is a work of tragedy with a plot around social taboo and a secret love affair which speaks about the idealism and romanticisation of the past. Look Back in Anger picks up on historical realism. Colonel Redfern, a character who admits being totally out of touch with the modern world is told by the character Alison that “You’re hurt because everything’s changed”, and that the main character Jimmy is “hurt because everything’s stayed the same”. Hence, our emotional disjunction with the past, with history, comes from either 1) being frustration with the lack of change in the present or the fear that our future will bring no new relief, or 2) that too much change is pressing upon our present and our fear that we lose what we value in the future.

It is an ancient conflict at the heart of history – history as pure change, chaos over time, or history as a stable pattern or teleology, a fixed structure over time. It is from Heraclitus that we have the former view. There are, in fact, several quotations associated with this view of Heraclitus, the most famous, “You could not step twice into the same river”. A fuller explanation from Heraclitus is the stanza:

Everything flows and nothing stays.

Everything flows and nothing abides.

Everything gives way and nothing stays fixed.

Everything flows; nothing remains.

All is flux, nothing is stationary.

All is flux, nothing stays still.

All flows, nothing stays.

The other view of history, one of fixed teleology, is a product of Plato and Aristotle’s wider philosophical arguments about the nature of things or being (ontology). At this point, the idea of history really did not come to the fore, from the ontological argument. It was not until Augustine of Hippo formulated a Christian teleological view that we get a clear idea of history as linearly structured towards Platonic final causes. Popular quotations on the static view of history are hard to find, but Augustine’s well-known commentary on ‘God’ and ‘Time’ captures the thought well:

For You [God] are infinite and never change. In You, ‘today’ never comes to an end: and yet our ‘today’ does come to an end in You, because time, as well as everything else, exists in You. If it did not, it would have no means of passing. And since Your years never come to an end, for You they are simply ‘today’… You yourself are eternally the same. In Your ‘today’ You will make all that is to exist tomorrow and thereafter, and in Your ‘today’ You have made all that existed yesterday and forever before.

In this teleological view purpose or design in the history is the same in every epoch. The medieval outlook saw human nature as the same, a constant battle between good and evil with very pessimistic expectations for human capacity. For Augustine the best and final outcome was the grace of God. However, the Augustinian view of history was also a linear progression toward history’s end. The radical parties of the Protestant Reformation (Unitarians, Quakers, and other English dissenters), influenced by greater optimism of the humanist Renaissance, separated out Augustinian historiography from its bleak determinism. Contra Augustine, there was the possibility of change in history, but the change for the good was never won easily and existed in the midst of a cosmic battle between heaven and hell. Seventeenth century saw the growth of millenarianism which mapped out history into stages with eschatological markers. John Bunyan’s The Pilgrim’s Progress (‘from This World to That Which Is to Come; Delivered under the Similitude of a Dream’, 1678) combines the doctrine of divine grace with the evangelical idea of a free agent who is on a long pathway towards redemption, with battles against temptation along the way. Even the deterministic Calvinists had a similar kind of idea of progression through the belief that increasing prosperity over time was the sign of divine grace.

By the eighteenth century these religious ideas were politically transformed into the Whig interpretation of history, as it was later referred to by Herbert Butterfield (The Whig Interpretation of History, 1931). The theological arguments were secondary to the new political discourse from the advocates of the Whig Party. It was a rather parochial outlook compared to the scope of world history, but the teleology was in the destiny of the British parliament to bring liberty to the whole of mankind. The continental Romantic Movement also had a teleology of liberalism. The cry of Jean-Jaques Rousseau, “Man was born free, and everywhere he is in chains” (L’hommes est né libre, et partou il est dans les fers), was a call for change where nationalist revolutionaries attempt to break out of the social imprisonment of the ancien régime. Rousseau had a different idea of change than most revolutionary progressives. He wanted humanity to return back to state of nature which he envisaged as a paradise of innocence. This was reversing Thomas Hobbes’ original idea of the state of nature (Leviathan or The Matter, Forme and Power of a Common Wealth Ecclesiasticall and Civil, 1651). Hobbes believed the state of nature was a ‘war of all against all’ (bellum omnium contra omnes) before the creation of civil society. These political movements of ‘progress’ had greatly shaped modern thinking, and thus popular historiography. Whether it is a belief in history as a movement from brutality to civilisation, or contrary, from innocence to imprisonment, and hopefully back to paradise, or whether a political fight for parliamentary democracy or the religious search for salvation, the concept of history as progression has been inescapable.

The twist in the debate between two basic historiographies of chaos and structure is that the homogeneity of change and ‘final causes’ means a coming together in perceiving history as single unity. There is another commonly quoted stanza of Heraclitus that is not very far apart from Augustine’s statement on time:

The past and present

Are as one –

Accordant and discordant

Youth and age

And death and birth –

For out of one came all

From all comes one.

As popular quotations, we commonly say, “The more things change, the more they stay the same”, and it is not uncommon to reverse the statement and come to the same conclusion: “The more things stay the same, the more they change”. The idea of the oneness of history, whether the indeterminate change or a teleological pattern, is a step into another historiographical thread.

Having one God, instead of many Gods, will save tons of money. Just in sacrificial lambs alone! Source: CartoonStock Order #282339, jcon3211_hi

History as One and the Many

The argument of ‘The One and The Many’ or ‘The One Over Many’ is a perennial metaphysical discussion. In modern philosophy it has had a new release of life, in the problem of identity, particularly personal identity. Am I the same person I was (say) twenty years ago? The connection here to the idea of history is apparent. The question is whether history, the past, is one, or is there just disconnected plurality. Archilochus, the ancient Greek poet, put it, “The fox knows many things – the hedgehog one big thing.” The same or different versions of the proverb appeared several times over the centuries. It was quoted by Plutarch, in Moralia, ‘The Cleverness of Animals’. Erasmus renders the idea in Adagio (1500); “The fox has many tricks, and the hedgehog has only one, but that is the best of all.” It was brought to modern attention by Isaiah Berlin in his well-known piece, “The Hedgehog and the Fox: An Essay on Tolstoy’s View of History” (1953) where he stated:

Scholars have differed about the correct interpretation of these dark words, which may mean no more than that the fox, for all his cunning, is defeated by the hedgehog’s one defence. But, taken figuratively, the words can be made to yield a sense in which they mark one of the deepest differences which divide writers and thinkers, and, it may be, human beings in general. For there exists a great chasm between those, on one side, who relate everything to a single central vision, one system, less or more coherent or articulate, in terms of which they understand, think and feel – a single, universal, organising principle in terms of which alone all that they are and say has significance – and, on the other side, those who pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory, connected, if at all, only in some de facto way, for some psychological or physiological cause, related to no moral or aesthetic principle. These last lead lives, perform acts and entertain ideas that are centrifugal rather than centripetal; their thought is scattered or diffused, moving on many levels, seizing upon the essence of a vast variety of experiences and objects for what they are in themselves, without, consciously or unconsciously, seeking to fit them into, or exclude them from, any one unchanging, all-embracing, sometimes self-contradictory and incomplete, at times fanatical, unitary inner vision. The first kind of intellectual and artistic personality belongs to the hedgehogs, the second to the foxes; and without insisting on a rigid classification, we may, without too much fear of contradiction, say that, in this sense, Dante belongs to the first category, Shakespeare to the second; Plato, Lucretius, Pascal, Hegel, Dostoevsky, Nietzsche, Ibsen, Proust are, in varying degrees, hedgehogs; Herodotus, Aristotle, Montaigne, Erasmus, Molière, Goethe, Pushkin, Balzac, Joyce are foxes.

In Berlin’s list only Herodotus and Hegel could be said to have a formative philosophy of history, but the two thinkers are clearly archetypical; one being the literary father of the discipline, and the other taking the discipline into its most ‘logical’ and structured genre. Herodotus’ The Histories (Ἱστορίαι) focused on the cultural and anthropological differences of the Ancient world. In contrast, Hegel’s Lectures on the Philosophy of History (Vorlesungen über die Philosophie der Weltgeschichte, 1770–1831) is the tome which sought to bring history into the one great metaphysical pattern of thesis-antithesis-synthesis (the dialectic). In fact, Hegel’s argument is that the history discipline has moved in three stages: from the original history of Herodotus and Thucydides, a matter of recording multiple deeds and events; to reflective history of those who impose interpretative framework, the cultural prejudices and ideas of the historians’ era which is shaping our understanding upon the past; and finally to Hegel’s own philosophical history, where the historian must bracket his [and her] own preconceptions and go and find the overall sense, the driving ideas out of the very matter of the history considered.

Few believe that Hegel achieved what he set out to do, but the idea of a stable oneness of history has stuck with the modern ‘hedgehogs’ against the supposedly ‘postmodern’ ‘foxes’. This is partly because of the claims on sameness of time, as discussed above. It was either the British writer Philip Gueoalla or Oscar Wilde who first said, “History repeats itself. Historians repeat each other.” There is a suggestion here of the cyclical view of time or of the eternal recurrence. There is a question, whether the cyclical view really put the matter beyond history. Such non-linear arguments focus on cosmology rather than human deeds and events, and are of little significance to the meaning of such historical paradigms. We will return later to this question. For the moment it should be noted that the very nature of what we understand as history is linked to those small incremental actions and events.

“This history paper is about an event that happened a long time ago, but in the great scheme of things isn’t all that important, making my report very short. The end!” Source: CartoonStock Order #282339, pkpn34_hi

History as Biography

Biography, the history of the one person in the incremental space, then moves the argument in the opposite direction of cosmological time; to reduce the whole cosmic past to a historical figure. “Cometh the hour, cometh the man” is a quote from John 4:23 and has since been countlessly recounted in slightly different versions. The ‘great man’, and more recently, ‘great woman’, has plagued the literary world, to the ‘great’ distaste of many social historians. The extreme libertarian view of Margaret Thatcher – “…there is no such thing as society” – has its roots in conservative populist enthusiasm for biography.

Ralph Waldo Emerson, a hero to both conservatives and radicals, quibbled, “There is properly no history; only biography” in his piece, ‘History’ from his Essays (1841). Nigel Rees explains in the Brewer’s Dictionary that Emerson means only that there is the primacy of experience over second-hand knowledge, and that what is read has no meaning for a person until it is directly experienced. Yet it is a misnomer as popular historiography. The argument collapses at the first hurdle. The vast majority of the past is beyond direct experience but there is no reason not to uphold the apparent meaning of distantly recorded history. Even Bernard Russell’s famous thought experience of the five-minute hypothesis – that everything was created only five minutes ago – shows the meaningfulness of an unknown or unknowable past, and it is a reasonable step from that conclusion to history (what is claimed to be known of the past) – where there is no strict experiential connections. Biography as history is too short sighted. This is well revealed in the quotation from Benjamin Disraeli, as one of Thatcher’s predecessors (British Conservative Prime Minister, 1804-1881), “Read no history: nothing but biography, for that is life without theory”. The social and philosophical historian asks what is life without theory, and it is certainly not a Socratic life, and nor is it an informed one.

“Atilla the Hun, sadly neglected by historians for his progressive approach to personnel management” Source: CartoonStock Order #282339, bven32_hi

History as Pessimism

Although there has yet to be definite studies on the question, one senses that the popularity in the formats of biography, and also oral history, is the psychological comforts it provides. The alternative of a more traditional history format is much more pessimistic. Surprisingly, for a theoretical utopian, it was Karl Marx who said, “History repeats itself – the first time as tragedy, the second time as farce”. He was discussing Hegal’s historical dialectic in The Eighteenth Brumaire of Louis Napoleon (1852), saying that Hegal forgot to see the repetition first as tragedy, and second as farce. Perhaps, Marx was not serious and was only adding humour to very dry Hegelian world, as he sort to turn it upside down. There was, however, an important idea here that the Communist successors took on-board. Although the dictatorship of the proletariat would complete history in the stateless utopia, the Marxist revolutionaries saw ‘history’ as something that was deposed. As Leon Trotsky put it in his History of the Russian Revolution (Volume 3, Chapter 10, 1933): “You are pitiful isolated individuals; you are bankrupts; your role is played out. Go where you belong from now on – into the dustbin of history!” There is a dispute about who Trotsky was directing his attack, the Kerensky’s Provincial Government in the Winter Palace in 1917, or the Mensheviks generally (as suggested by E.H. Carr in his Socialism in One Country, 1958)? The concept, though, is clear. History is a place where you put your rubbish.

There are those, however, who can find hope in the hopelessness of history. The Irish Poet, Seamus Heaney, exclaimed:

History says, Don’t hope

On this side of the grave.

But then, once in a lifetime

The longed-for tidal wave

Of justice can rise up.

And hope and history rhyme.

It is a stanza of The Cure at Troy (1990), Heaney’s retelling of Sophocles’ Philoctetes, and is associated with Ireland’s drive towards self-determination, quoted by Mary Robinson at her inauguration as the Irish President in December 1990. It is also said to be a particular favourite poem of the American Vice President, Joe Biden. Hence, history’s realism is not necessarily tied to a destructive hopelessness; something is saved in the past that has value and is able to continue towards a final victory.

“I’m sick of history – is there never an end to it?” Source: CartoonStock Order #282339, twln900_hi

The End of History

If history is not a pessimistic determinism, what is more commonly called ‘fate’ or ‘fatalism’, the alternatives are history as a collection of accidental events or history as a kind of progression. The idea of historical progression came to dominate the outlook of most of the twentieth century, until the failures of civil rights movements and environmental reforms since the 1980s created a generally more pessimist mood (again; it seems we have been here before). The American Progressivist Movement, along with the stage of United States history called the Progressive Era (1890s to 1920s), was a model for other westernized societies. This is a large topic in historiography linking themes and ideas back through the nineteenth century to the era of the eighteenth century enlightenment. As a too concise synopsis, the historical idea of progress draws from the arguments of Voltaire (François-Marie Arouet, 1694–1778), and Immanuel Kant (1724–1804), and among other writers of the European Enlightenment. It gained a specific political paradigm in the new nation of the United States with the liberal doctrines of Benjamin Franklin (1706-1790), Thomas Paine (1737-1909), Thomas Jefferson (1743-1826), and John Adams (1735-1826). The Idea of Progress would also have other branches, developing concepts of scientific progress or scientific revolution, social progress, economic development and the ideas of prosperity and growth, and technological change. All these concepts, including those belonging to American liberalism and republicanism, feed back into the historiography of progression. In the nineteenth century the historiography of progression was theorized by Whig historians, particularly Thomas Babington Macaulay (1800-1859). British political philosophers and ethicists, namely the utilitarian John Stuart Mill (1806–1873), also contributed to the historiography with concepts of social and personal improvement. Herbert Spencer (1820–1903) brought ideas of social evolution and harsh libertarianism into play. It is largely from these different threads in the Idea of Progress that the concept of Modernity was put together.

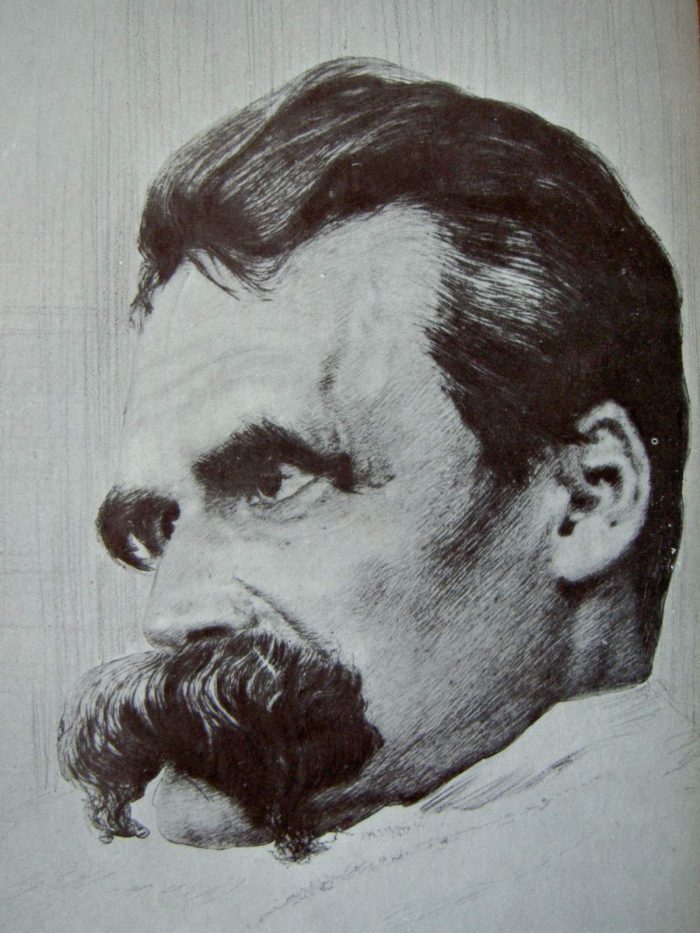

The challenges to the modernist conceptions were the reasons that the pessimism returned. The Idea of Progress failed on reflections regarding the Marxist (or other socialist) utopias unrealized, on most violent violation of human rights in the holocaust and other noted genocides during the century, with the failure of international peace movements, and on the almost untouchable global environmental damage and the lack of economic and political will to take radical action to save the planet. The ill-defined Post-Modernist movement (c. 1980s-2010s?), however, went much further than repudiating the Idea of Progress; it reject any concept of progression in history, preferring a return to the flux of Heraclitus. However, such an assessment goes too far and is short-sighted for two reasons. It overlooks that the fact leading theorists of a pessimistic historiography in the nineteenth and early twentieth century still could not do without an idea of progression, and it was merely replaced from linear to cyclical progression. For Thomas Malthus (1766–1834) it was a case of a rebalance of the socio-economic ratio once the population had collapsed. For Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) it was the classical model of ‘eternal recurrence of the same’. The cyclical theory of history was clearly described by Oswald Spengler (1880–1936) in The Decline of the West (1920). The more optimistic Arnold J. Toynbee (1889–1975) developed the modernist cyclical theory of history into the multi-volume study of civilizations, A Study of History (1934–1961). These were not merely the ancient cosmic cycles but spoke of the spiralling affairs in history of the human species.

Secondly, a repudiation of history as progression destroys the very valuation of the failures that led us back to pessimism. The Progressive Era was a period of widespread social activism and political reform, not only for the United States, but for the countries of New Zealand, Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom, what was the Anglo-Saxon political settlements of the British Empire (and very material invasions of indigenous lands). Other nations, on the landmasses of Europe, Africa, the Middle East and Asia, also had their history of socio-political reforms. This era of progressivism was the undoing of imperialism, and while very uneven in its progression, without these ideas there would have neither been Gandhi nor Nehru. The Post-Modern in latching onto the ethical failure of the Progressive Era – the managerialism, the scientism, and the social puritanism (Prohibitionism) — failed to acknowledge the achievements – the movements against political and economic corruption, beneficial health regulation, anti-child labour laws and enforcement, family welfare benefit schemes, women’s and minorities’ enfranchisement, the peace movement, and a belief in the value of humanity if not a renewed humanism. Without those Progressivist achievements the Post-Modernist has no basis to judge the last half of the twentieth century as a total modernist failure.

The historian J.B. Bury provided the better perspective, the more reasonable one, on the historical conception of progression, when he wrote in The Idea of Progress (1920):

To the minds of most people the desirable outcome of human development would be a condition of society in which all the inhabitants of the planet would enjoy a perfectly happy existence….It cannot be proved that the unknown destination towards which man is advancing is desirable. The movement may be Progress, or it may be in an undesirable direction and therefore not Progress….. The Progress of humanity belongs to the same order of ideas as Providence or personal immortality. It is true or it is false, and like them it cannot be proved either true or false. Belief in it is an act of faith.

A modest skeptical view paves the way to remove the faith in a never-ceasing linear Progress, but retains always the possibility of history as progression. So why is Postmodernism incredibility hard on hoping for a better future while retaining the structured habits of the past? The phrase ‘Postmodernity’ clearly suggests a new structural stage in history and it is one which I suggest is linked to the New Millennialism. By this term I mean a renewed eschatological obsession around the idea of a thousand years and the host of theories of how the end of history is to be played out. In the nineteenth and twentieth century it has had significant global influence through the American evangelical revivalism, however, different versions of modern millennialism are formative in other religious and secular cultures as well. The idea of millennialism is very present in popular historiography, even in very subtle ways. In light of the recent referendum in the United Kingdom where the country decide to ‘brexit’, it is interesting to see the use of millennialism in earlier fears around Britain emerging into the European community. On 14 February 1948, speaking on the subject of European unity, Winston Churchill said, “We are asking the nations of Europe between whom rivers of blood have flowed, to forget the feuds of a thousand years.” Although Churchill was not deliberately being apocalyptic, his words plainly conjure that image. On the other side of politics but with the same millennial vision, Hugh Gaitskell, at the Labour Party Conference in October 1962, and speaking on a proposal that Britain should join the European Economic Community, stated, “It does mean, if this is the idea, the end of Britain as an independent European state… it means the end of a thousand years of history.” A different kind of millennialism, an utopian one, came at the end of the century when Francis Fukuyama, declared, “What we may be witnessing is not the end of the Cold War but the end of history as such; that is, the end point of man’s ideological evolution and the universalization of Western liberal democracy.” Fukuyama’s well-known proclamation came in the Summer 1989 edition of National Interest, during the collapse of the communist paradigm in the Soviet Union. The idea that the collapse of Soviet Communism would remove the last systematic challenge to the triumph of the capitalist system was very premature to say the least. History continued with about 24 major national and global economic crises since 1989 and the ill-named ‘war on terrorism’ since 2001.

‘Drawing by Hans Olde, 1899’ Source: By Hans Olde – Reproduction of a reproduction on a book cover, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=205102

The Desirable Absence of History

Fukuyama’s neo-liberal end of history was closely associated with the Post-Modernist Movement in last days of the 1980s. Daniel Zamora’s revelation, in 2014, of Michel Foucault’s sympathy for neoliberalism strengthens the argument that de- historicization in postmodernity was not radical, but a push to keep the global socio-economic systems from away from reform towards equity and fairness. The Post-Modernist’s rejection of a distinctive history discipline for disassociated stories aligns with an old conservative’s desire for the absence of history. Nigel Rees in Brewer’s articulates the genealogy of this idea of an absent history. According to Rees in The French Revolution – A History (1838), Thomas Carlyle had explained the original steps; “A paradoxical philosopher, carrying to the uttermost length that aphorism of Montesquieu’s, ‘Happy the people whose annals are tiresome.” has said. ‘Happy the people whose annals are vacant’.” The saying was also ascribed to Montesquieu by Carlyle in his History of Frederick the Great (1838-1863), in the form, “Happy the people whose annals are blank in history-books!” George Eliot (Mary Ann Evans) makes the statement even stronger in the novel The Mill on the Floss (Book 6, Chapter 3, 1860): “The happiest women, like the happiest nations, have no history.” What is meant by the absent history is the absence of defining moments in striving for achievements, whether successful or not. This is seen in a speech 10 April 1899 from the imperialist Theodore Roosevelt:

It is a base untruth to say that happy is the nation that has no history. Thrice happy is the nation that has a glorious history. Far better it is to dare mighty things, to win glorious triumphs, even though checkered by failure, than to take rank with those spirits who neither enjoy much nor suffer much because they live in the grey twilight that knows neither victory nor defeat.

The heavy cost to other nations and communities from such ambition is certainly a significant part of the history as well. The point, nevertheless, is that history, as to life, is never mere existence, but the essence which follows (l’existence précède l’essence). This is true for ‘history from below’ as it is for traditional national histories.

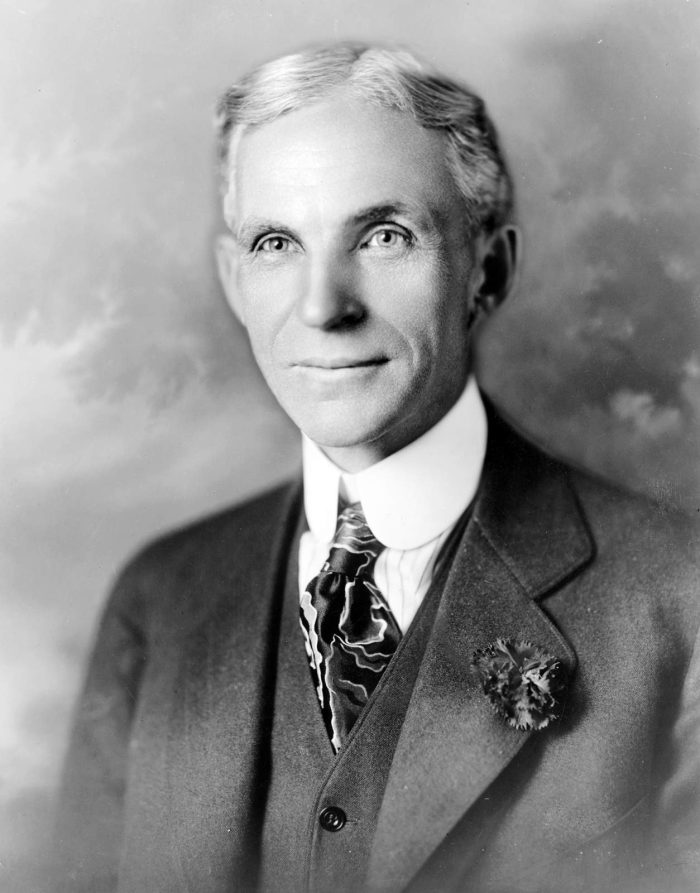

‘Portrait of Henry Ford (ca. 1919)’ Source: By Hartsook, photographer. – Library of Congress. This image is available from the United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division under the digital ID cph.3c11278. Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=531177

Conclusion

The misconceptions of history from quotations, quips, antidotes, and other popular expressions becomes understandable once we examine the genealogy of these thoughts and compare them to the evolving and diverse historiographies. There are, perhaps, two types of misconceptions of what has been considered. There are the ‘All-or-Nothing’ misconceptions. The popular quotations give a view that history is either always from the present or it is it only the past. It either traps us in the past or cast us into the future. History is either flux or structure. It is either static or progression. It promises salvation or dooms us to despair. History is the one or the many. It looks inward or outwards. History has final ends or it is just play-time. Simplistic dichotomies rules in popular historiography and it brings such misunderstanding about history as a discipline. The result is the other kind of misconceptions, the ones where is history is removed completely – the anti-history. History is replaced by the fiction of the novel, theatre, and film. Drama is everything and detailed description and explanation of the past are nothing. The annals are vacant. History is bunk.

In the Brewer’s dictionary, Rees has the story that Henry Ford explained of his famous quotation, “I did not say it was bunk. It was bunk to me… but I did not need it very bad.” The original source of the quotation was from an interview of Charles N. Wheeler with the motor magnate on 25 May 1916, and where Ford is said to have exclaimed, “History is more or less bunk. It’s tradition.” The quotation came to prominence in 1919 during a libel action Ford took against the Chicago Tribune. The newspaper editorial had described Ford as an ‘anarchist’ and an ‘ignorant idealist’. It is revealing to know that the court case did not go well for Ford, in that his ignorance of history was demonstrated publicly during cross-examination over a period of no fewer than eight days. Ford could not say when the United States came into being, and first suggested the answer of 1812. Although the Tribune was found guilty of libel and fined six cents, Ford’s ignorance of history had clearly shown that the field was not tradition, but a discipline, and in ignoring it, the danger is, not ‘playing the fool’, but being the fool, all the way through a past.

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- Dear grossly, ethically, corrupted - December 21, 2024

- Thoughts with a Professional History colleague on “Artificial Intelligence” - December 21, 2024

- Stephanie M. Lee on “AI by omission”, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Thursday, December 19, 2024 - December 20, 2024