THREE ESSAYS (REVIEW COMMENTS) IN ONE ESSAY

An examination of D.H. Lawrence’s Kangaroo (The Cambridge Edition) in social philosophy, and demonstrating a fundamental policy problem in Australian political history.

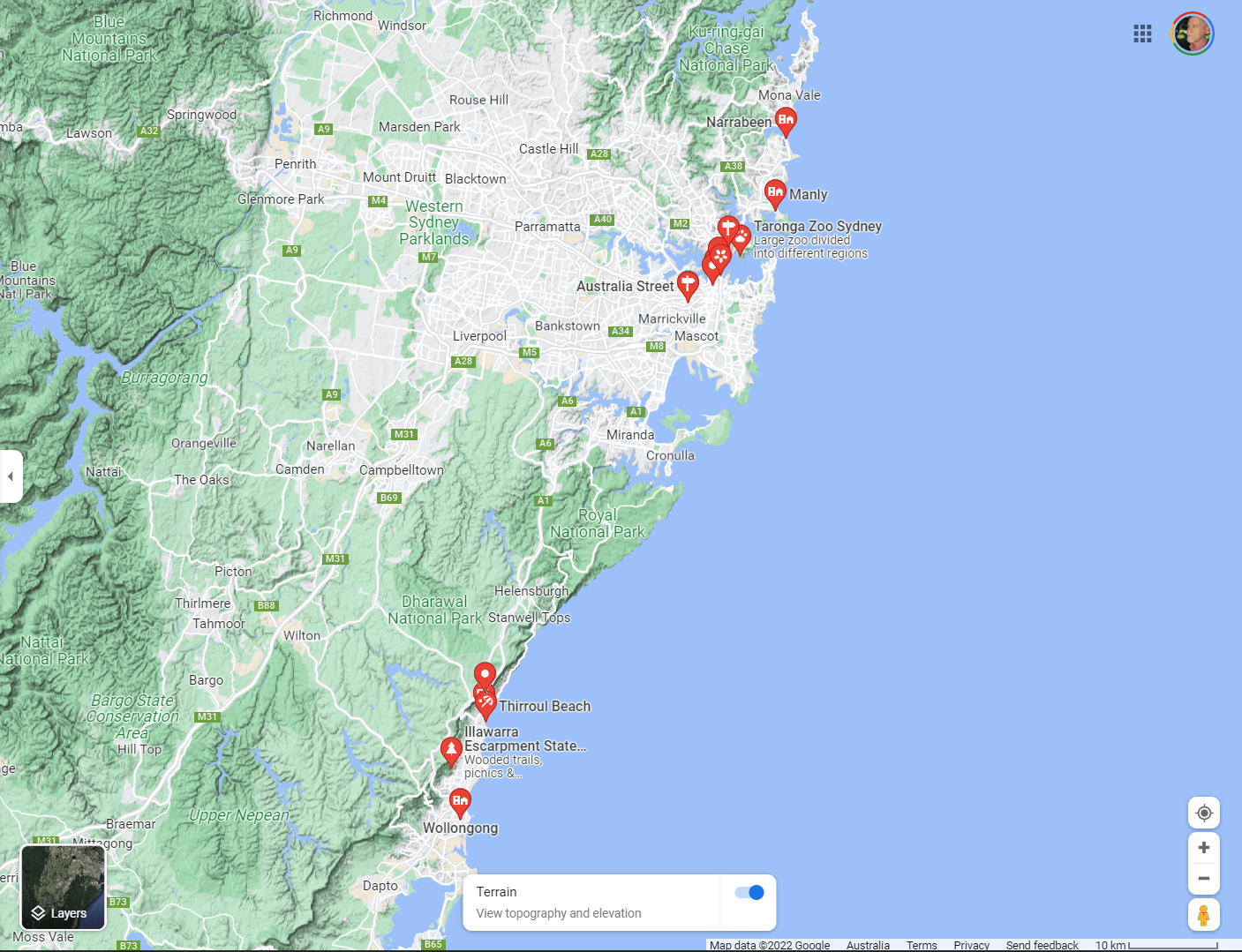

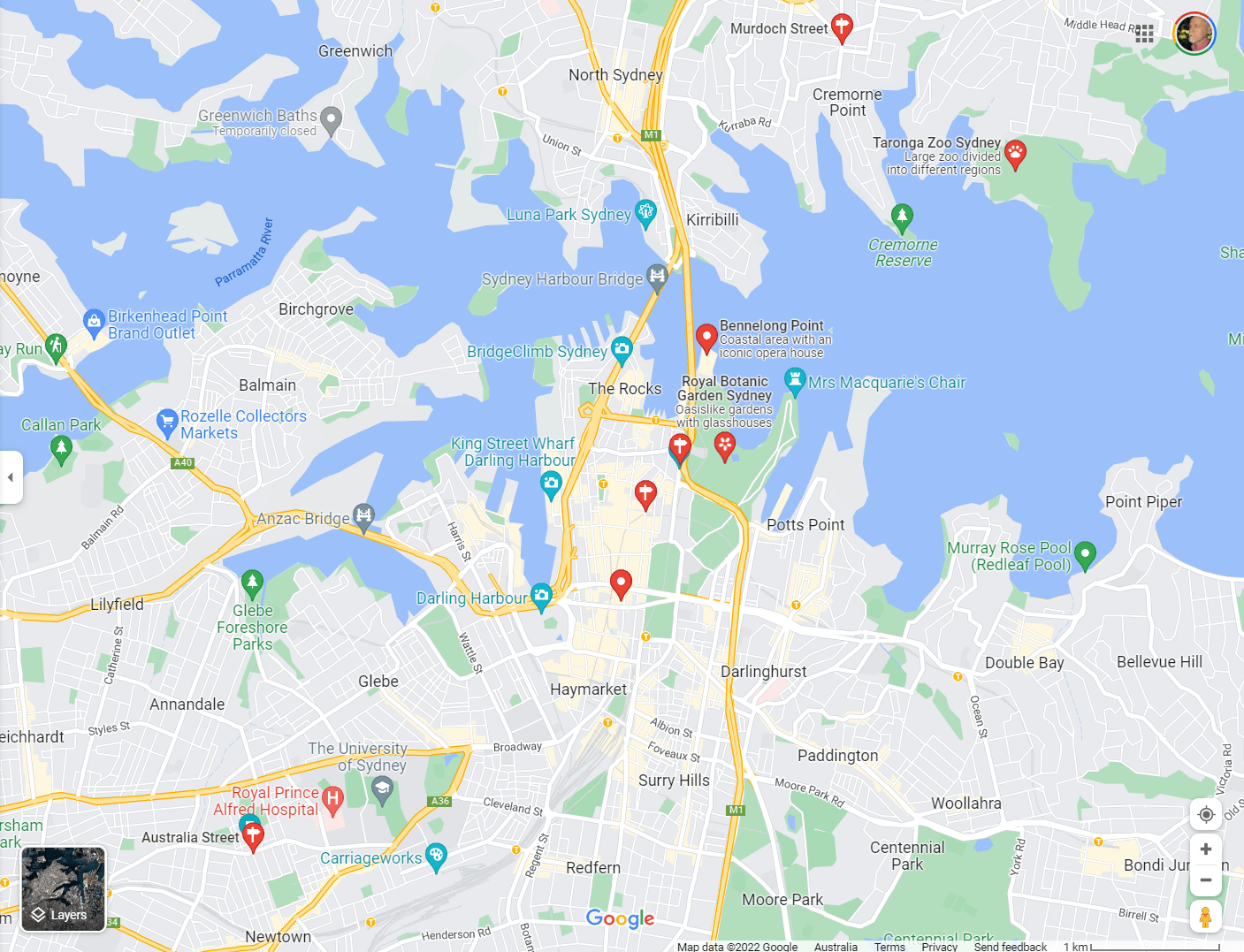

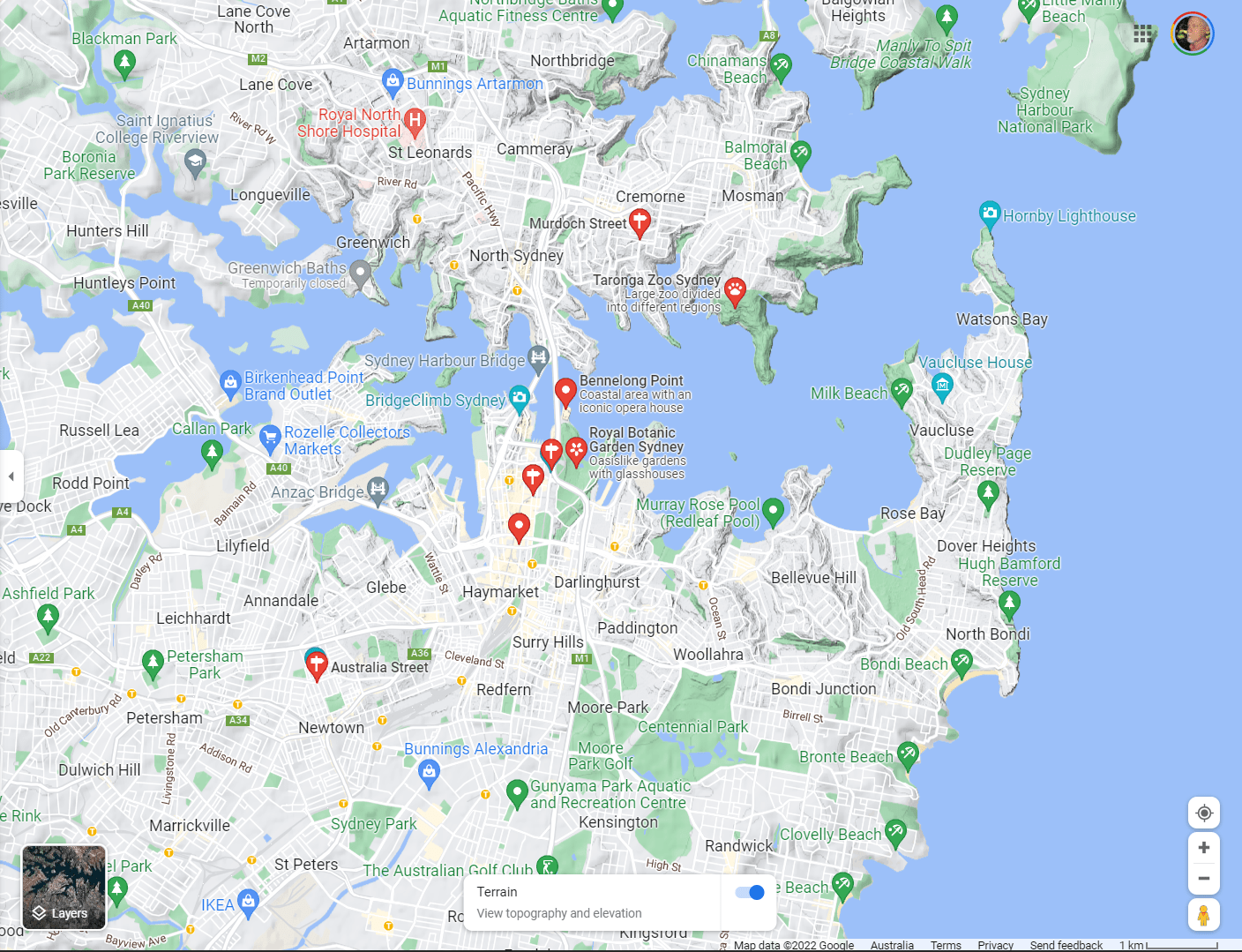

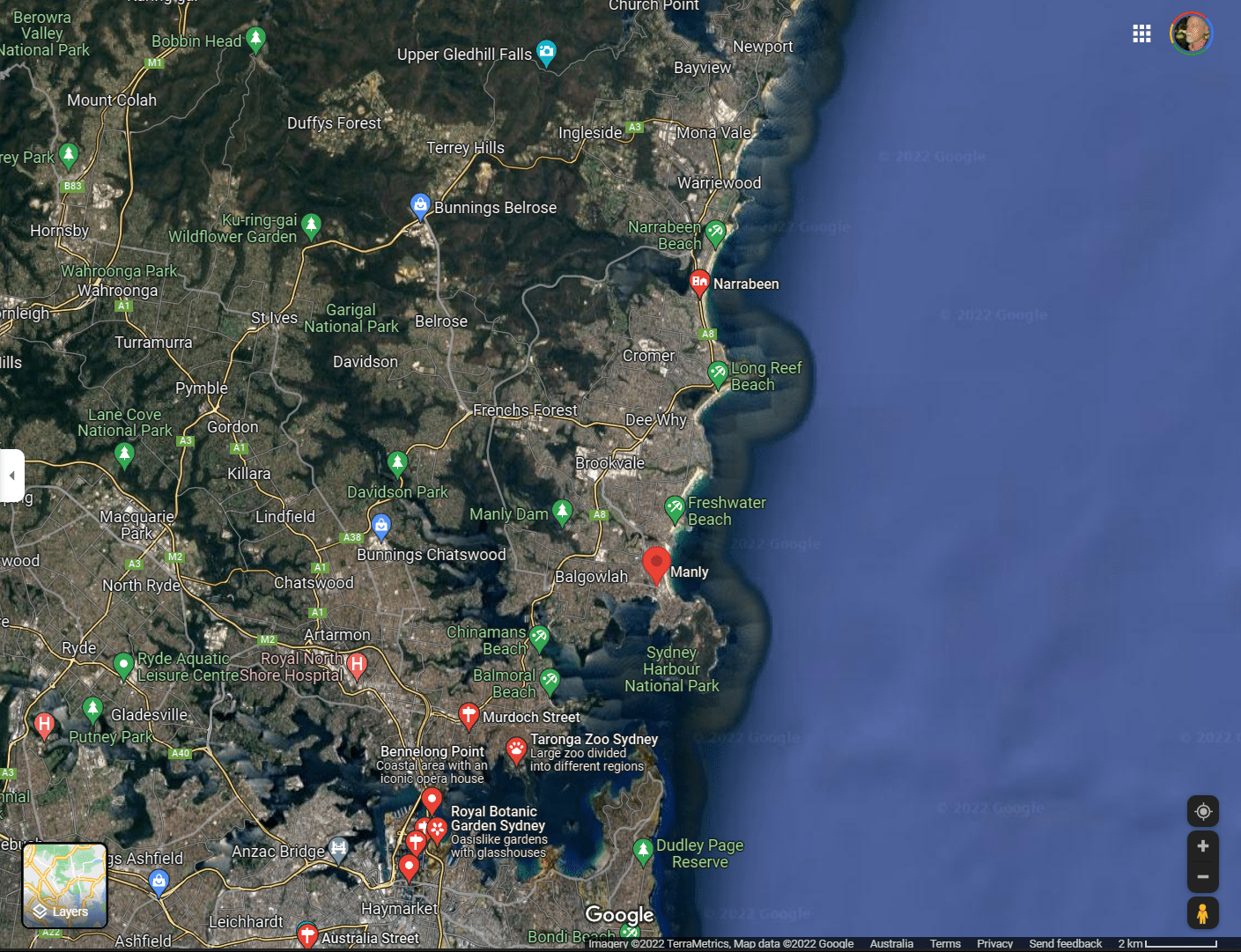

Image: Sydney Region and Central-South Coast Staging of Kangaroo (1923).

*****

List of Site Markers.

Order from north to south

Narrabeen

New South Wales 2101

One of three of the novel’s descriptions of the Pacific Ocean with its Australian coastal landscape.

Manly

New South Wales 2095

One of the three novel’s descriptions of the Pacific Ocean with its Australian coastal landscape.

Murdoch St

The name for the novel’s Sydney residential centre, but does not match the novel’s geographic location. Nevertheless, several descriptions of the Harbour views, from the described residences of minor characters, match the area.

Taronga Zoo Sydney

Bradleys Head Rd

Another flora and fauna centre of the novel.

Bennelong Point

As the site of the P. & O. Terminal, in Sydney, which is the site of both the beginning and end of the novel. P. & O. refers to Peninsula and Orient, inferring the Indo-Pacific colonialism.

Royal Botanic Garden Sydney

Mrs Macquaries Rd

The first flora and fauna centre for the novel.

Macquarie St

Where the novel begins, and remains as a social-political centre throughout the larger image of the story.

‘Canberra Hall’ (MacDonnell House), 315-321 Pitt St

Sydney NSW 2000

Another socio-political centre of the novel as Canberra Hall, Macdonnell House as history.

Martin Pl

Another socio-political centre of the novel.

Australia St

The site of “Murdoch Street ” of the novel, according to the description of the novel’s geographic location.

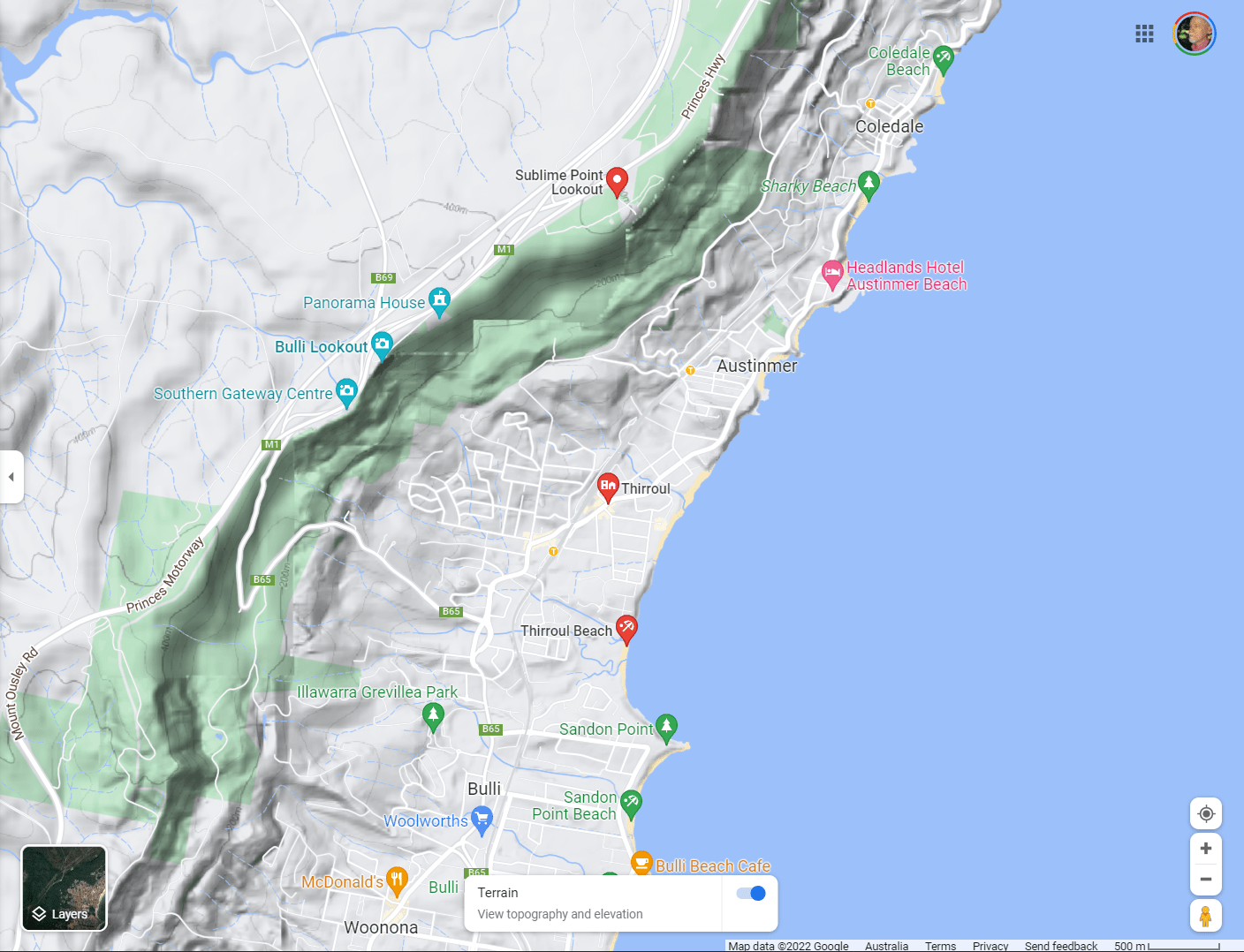

Sublime Point Lookout

661 Princes Hwy, Maddens Plains NSW 2508

Another area of flora and fauna descriptions in the novel, and inland to Loddon Creek.

Thirroul

New South Wales 2515

Main area of the novel.

Thirroul Beach

One of the three novel’s descriptions of the Pacific Ocean with its Australian coastal landscape.

Illawarra Escarpment State Conservation Area

Another flora and fauna centre of the novel.

Wollongong

New South Wales 2500

Major city in novel, outside of Sydney.

*****

KANGAROO. REVIEW COMMENT 1: INTRODUCTION AND GEOPOLITIC-MAPPING OF THE NOVEL

The book will disturb some readers for good reasons. The description of racism, antisemitism, the whitewash on Aboriginal histories, the overblown masculinity matched with the sympathetic-but-disempowered feminism, the strange conflations of Nietzsche, Freud, and Jung, in British Christian thought, all is there in the now-lost landscape of 1920s Australia, or at least 1920s Central-South region of New South Wales. The book is disturbing for those who know the history, as much as for those who do not, and for this reason it is the most beautiful book of Australian literature, albeit written by an Englishman looking from the outside-inward. In the end, the main character, a pale reflection of the author (perhaps), “love Australia”, and departs the land as an ‘Australian’ of sorts, or as an image of 1920s Australia. What is wonderful about this book for an Australian, or anyone interested to understand Australian history and culture, or to be exact, the national mythology, is that it provides the architecture of the intellectual frameworks which is recognised as the ethos and landscape of 1920s Australia, and beyond its NSW locality as the staging, and yet we are left with serious questions about how much of that Australia has actually disappeared, a century ago.

One landscape which overshadows the present, which is much less than what it was for the novel of the 1920s, is economic rhetoric: bloated promises, and hyped warnings. The global-flying ship, ‘Social Philosophy’, and its policies tends to, in these contemporary times, sink serious socio-political thought by the economic hype and rhetoric. It is not that economics should not have some serious consideration, but it has become such a political game, since 1945, a mechanism to the more critical question of how we should live together. In the other post-world war world, that of the 1920s, the economic model was either, one, the hype of Wall Street and the conservative view of minimal government and non-interference, two, as the hostile reaction to the zeitgeist, the hope in revolution (right or left) where a regime totally set both social and economic policies. The second post-war world (1945-1989) achieved this position without revolution in places like Australia, and contra the United States with its obsessions with markets. The contemporary world (1989-present) has become more a re-working from the 1920s: ideological rhetoric but this time in the denial of its ideological ontology, the distrust of government and the high hopes in minimal government (in contradiction to the continuing reality), and hype in market models. Missing is considering social philosophy and its policies on its own terms. Kangaroo can assist. To be successful the geo-politics has to be mapped on the locality.

Image: Central-South Coast Staging of Kangaroo (1923). See List of Site Markers above.

KANGAROO. REVIEW COMMENT 2: THE PHILOSOPHICAL MAPPING OF THE NOVEL

Make no mistake, Kangaroo (1923) is a serious work of social and ontological philosophy. For all of the references to Australian ‘indifference’ and a lack of serious care, the novel holds serious philosophic commentary for the world of the 1920s. Australia is ‘a new country’ as a blank canvas, the tabula rasa, and the writer’s first blank page. This, no doubt, whitewashes the Aboriginal persons, landscapes, and histories. The world and Australia, however, was in the grip of the World War I depression, psychic depression, and not economic depression which fools are so obsessed with; although through the historical pathway of the 1920s and 1930s the two are well linked. It was an era of isolationism, as well as soft racism – ‘we do not begrudge the rights of ‘brother brown’ or ‘brother yellow’ but their affairs are completely separate to ours’.[i]

The ontology and sociology are very mixed, and reading the novel inspired my composition and design for The Ontological Compass. It was a design to get my bearings on all of the proposed arguments from the novel’s characters, and the idea of character-personality is central to the argument of these essays. It is not a case of reading into the novel the philosophic frameworks. D. H. Lawrence knew the literature of his time.[ii] He began his writing career, in 1908, with a teaching certificate from University College, Nottingham (then an external college of University of London). True, he had an education of the world – a wanderlust which took Lawrence to Australia, Italy, Ceylon (Sri Lanka), the United States, Mexico and the South of France. But let that be no nasty populist quip against the education of book learning. It is for this reason that the Australian cultural themes of equality and individualism is explored at depth between the rhetoric of Benjamin Cooley –the ‘Kangaroo’ of the novel – and of the nemesis in Willie Struthers. There is a strange mixing of the ideals, where Cooley articulates the Australian (proto) version of fascism and Struthers the Australian Soviet spokesperson.[iii] Australian fascism is killed, in that Kangaroo is killed from the violent melee in the block bounded by Pitt and George Streets, Sydney (Macdonell House, ‘Canberra House’ in the novel).[iv] The novel’s historical reference is to the NSW ‘Red Flag’ demonstration of 1921 but the Queensland Red Flag Riot of 1919 is more informative.[v] Other violent clashes happened over the period.[vi] With the novel published in 1923, there is an eery reference forward to the 1930s New Guard movement, a secret anti-communist militia, however, whether organised or not in the 1920s (as a suggested ‘Old Guard’), the bitter Digger sentiments were there.[vii] Kangaroo lingers from his terminal wounds in hospital, and it is in the final dying conversation between Cooley and Somers that the key message of the novel is revealed. Lines of class distinction and ideology are untangled and re-designed.

It begins with Somers (the voice of Lawrence?) declaring that the educated classes (or the ‘educated world’) had “preached the divinity of work at the lower classes.” What the new Soviet world of the working classes then done was to create the sacredness of work, according to Cooley, and what this did was to prevent the knowledge and practice in the ‘love of man.’ Work sucked the love out of mankind, or at least the masculine side of humanity. There are here key messages from Christian, Fascist, and Communist thought. Throughout the whole novel, the Australian proto-fascists (not yet in the full-blown version of Benito Mussolini, and more a form of militarism) are trying to rescue some version of the human commune while worshipping the egoistic and the heroic individual. Here the different visions were either a fascist bureaucracy making the trains run on time or making the world safe for/from (mob) democracy.[viii] On the other hand, the Australian Labour movement, politically and more successfully-represented in the Australian Labor Party (ALP), modifies its reformed Fabian ‘communism’ (British socialism) with the landscape’s rugged individualism. Each man a king in his own ‘castle’ (‘bungalow’ in the Australian vernacular), and with the sympathetic-but-disempowered feminism. In the end, though, all Struthers wanted was a generalised love in the brotherhood of the workers, but the coloured and indigenous brotherhoods were of no real concern to the revolution. In the end, though, all Cooley wanted was for the individual Somers to love him, like the beloved dictator Benito Mussolini needed to be loved. Both Cooley and Struthers saw themselves as ‘of the People’, but that worldview was a terrible conflation of persons and masses. In the end, though, Somers rejected both Struthers’ ‘generalised love’ and Cooley’s ‘say you love me’. Tying this together was the God of love and fear, and Somers’s decision for the ‘dark God’.

ENDNOTES FROM THE EXPLORARY NOTES (EN) OF THE CAMBRIDGE EDITION (Repeated)

[i] EN. 311:24

[ii] EN. 190:16

[iii] EN. 193:2

[iv] EN. 185:14

[v] EN. 313:22; Raymond Evans (1988). The red flag riots: A study of intolerance. St. Lucia, Qld.: University of Queensland Press.

[vi] EN. 314:33

[vii] EN. 259:28; 320:34; The idea that Lawrence drew on the existence of organised secret armies in the 1920s (‘Old Guard’), rather than the 1930s (‘New Guard’) goes to the work of Andrew Moore.

[viii] EN. 296:24

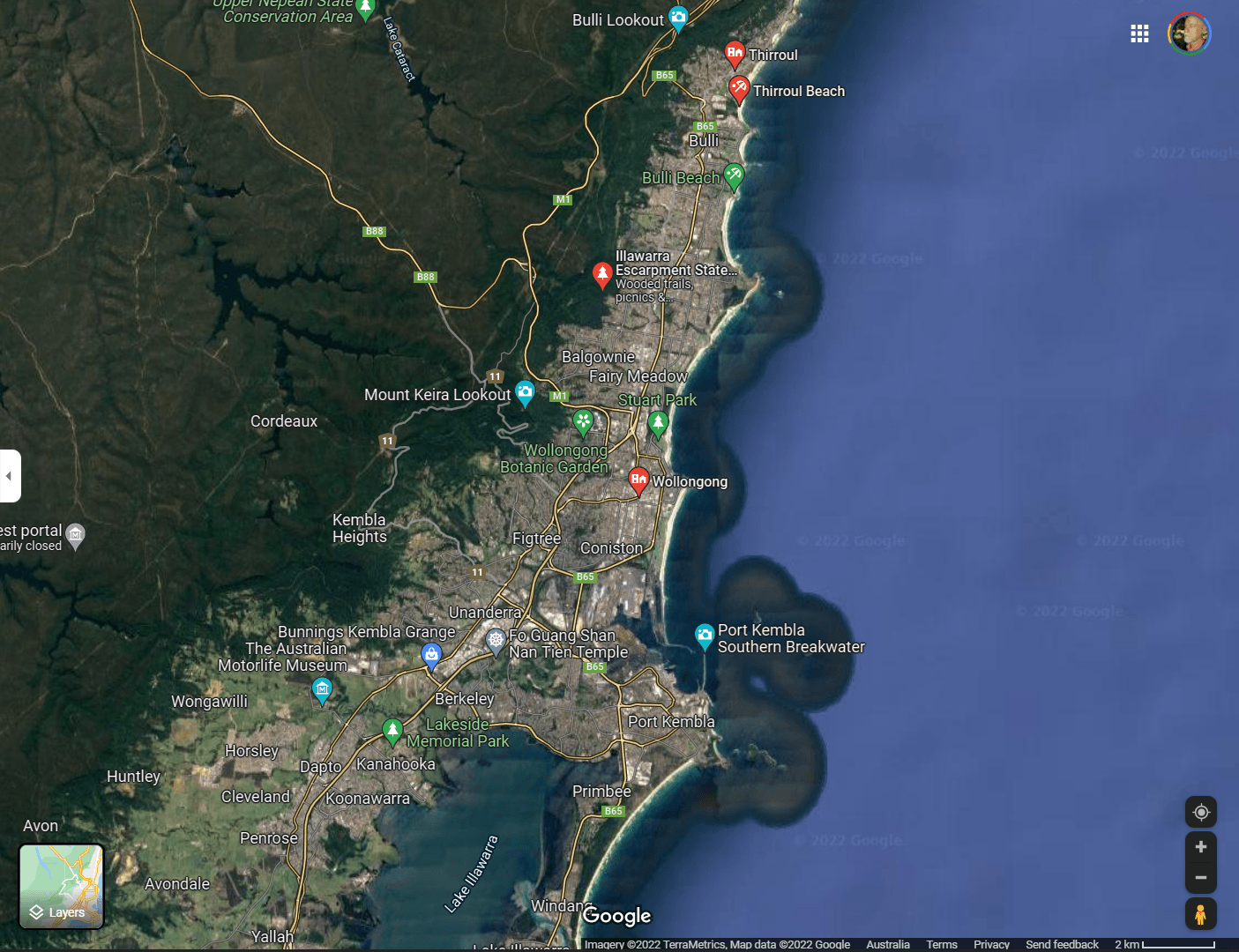

Image: South Sydney/Botany Bay-Central-South Coast Staging of Kangaroo (1923). See List of Site Markers above.

A ’god/God’ is a metaphor device which a writer will use to unify multiple themes and messages. Theologians and other religious thinkers would accept that basic idea, whatever literalism is accepted or rejected. The religious dogmatists and fundamentalists use ‘god/God’ as a political device to unify a nation, and the analysis, across the three sub-essays here, will show that, when we arrive to the final questions, we should put to death such ‘god/God’, although this to confirm the metaphorical truth and condemn the literalist falsehood.

So, my argument is that Somers-Lawrence’s ‘dark-God’ unifies several themes into a key message:

- Freedom (‘perfect love’) and Orthodoxy (each man, or the love itself, kills the thing it loves);

- Masculine Comrades (Walt Whitman) and ‘the Woman’ (who must be obeyed, Harriet/Freida);

- Mob Psychology (American Eric Hoffer) and Fabian Democratic Socialism (the folkish William Morris);

- Humanism (‘the global perspective’) and National Culture (‘the Australian perspective’);

- Sociobiology (ecology and biogeography, Wilfred Trotter, Louis Berman, E. O. Wilson) and Personality-Character (Personalism); and

- Cultic-Magical-Mythical Beliefs and Sacrifice-Martyrdom (James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough: A Study in Comparative Religion, themes examined in the last sub-essay).

Often the themes overlap in various conceptions in world literature, across the humanities and social sciences. The unity is bringing various landscapes (including seascapes) into the single personality of Australian culture, which (and here is the key problem) is politically described as a federation. The concept of the ‘Commonwealth of Australia’ is depended on the actual federation, and not merely the federation rhetoric. The third sub-essay explores this problem.

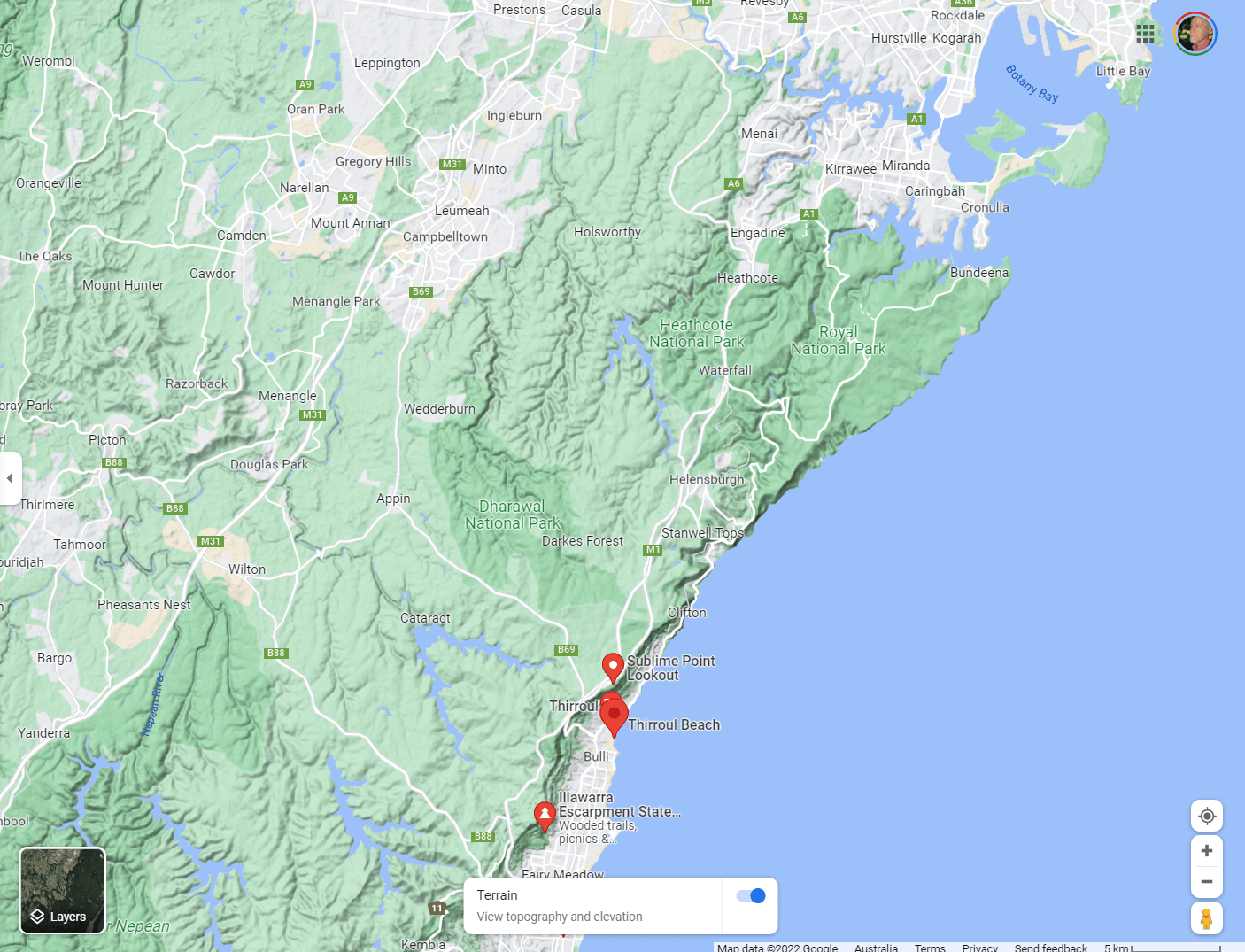

Image: Sydney Region Staging of Kangaroo (1923). See List of Site Markers above.

To the ideological sub-themes which crosses ideological boundaries, I say something in summaries which ‘The Cambridge Edition’ has extensive notes, and its own introductory essay and appendix, and extensive textual/manuscript notes (of this latter part I have not engaged; these are philosophic-history essays, not literary criticism). For further details, it is recommended to go to this work, and also to the work of Joseph Davis, in the two texts for D.H. Lawrence at Thirroul (1989, 2022 online).

The themes of Freedom (‘perfect love’) and Orthodoxy (each man/or love itself kills the thing it loves) speak loudly to those who have ears to hear. It is a theme that bean-counters are deaf to, with tragic literature remaining unread and unthought.[i] It easier to ‘count-down’ bureaucratically than to activate the mind. If D.H. Lawrence had written the novel today, Clive Palmer, the maverick would-be politician from Queensland, would have been the model for Kangaroo. His billboards screamed ‘Freedom’ as perfect love. It is all rhetoric and without any careful policy crafting from social philosophy. Nietzsche expressed it well when he said, “‘Freedom’, ye all roar most eagerly: but I have unlearned the belief in ‘great events,’ when there is much roaring and smoke about them.”[ii]

The original text in the novel made references to ‘Orthodox patriotism’ and ‘Orthodox religion’ where “The very word freedom is a satire in itself…”.[iii] There is often in the discourse a shying away from the critique of orthodoxy, with heresy (‘hearsay’) still stands out as albatross around a person’s neck. Lawrence still made the critique by the chapter on marriage, with Somers’s critique of ‘perfect love’ in metaphors of the Pacific Ocean and the literature, in Melville’s Moby Dick (1851)[iv] and Coleridge’s The Rime of the Ancient Mariner (1797): marriage as the albatross around the neck, with the partner killing the beloved in perfect love.[v] The reference to the song, Plassir d’ Amour, had the words, “The joy of love lasts but a moment; its sorrow ‘lasts for a lifetime’.”[vi] The widower, the widow, knows this truth deeply.

The theme of Masculine Comrades (Walt Whitman) contrasts with the theme of ‘the Woman’ (who must be obeyed, Harriet/Freida).[vii] The sorrow of this widower lies in that struggle between Australian ‘mateship’ and the deeply-loved woman for whom deep conflicting passions arise: love and fear, freedom and obedience. It is all there still from another lost world. Lawrence connects his introduction of the Australian emerging notion of ‘mateship’, from the 1890s bush mythology with Walt Whitman’s ‘Love of Comrade’[viii] which was reformulating in the ANZAC mythology of the 1920s.[ix] In the last 30 years many Australian social historians have written on the interconnections of all of these themes – masculinity, femininity, mateship, love, marriage. However, in the themes of the bush and ANZAC mythologies we find polemicists who makes lies or falsehoods about our humanity and the histories to our collective face. Curse these deaf idiots!

[i] EN. 198:32; 313:22

[ii] EN. 101:32

[iii] EN. 169:22

[iv] EN. 279:2

[v] EN. 169:22; 169:32

[vi] EN. 43:19

[vii] EN. 132:8

[viii] EN. 197:25

[ix] EN. 46:16; Australian and New Zealand Army Corps (ANZAC).

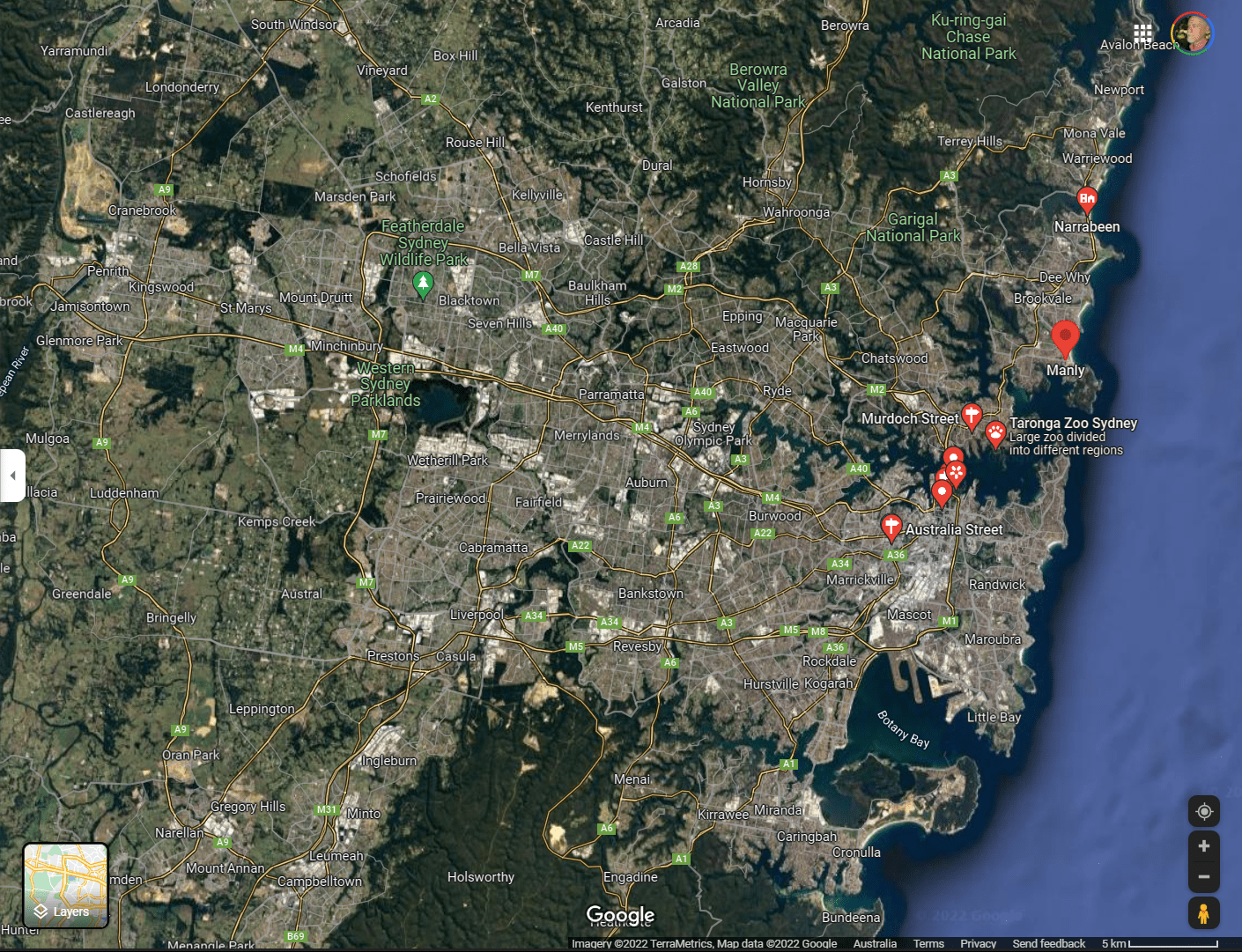

Image: Sydney City Staging of Kangaroo (1923). See List of Site Markers above.

The problem of Mob Psychology[i] stands out in the novel, and is juxtaposition with the quieter Fabian Democratic Socialism (the folkish William Morris).[ii] The novel makes passing references to writers who argued that masses had lost their authentic humanity, such as Feodor Dostoievsky.[iii] The Cambridge Edition connects the Fabians with Lawrence’s interest in William Morris and the British folk movements, and with Lawrence’s connections to the Mid-Lands and Cornwall. The Fabian Society (founded on 4 January 1884 in London) had a wider ideological scoping, a forebear of the British Ethical and humanist movements, and with the earliest members (then called ‘The Fellowship of the New Life’) being poets Edward Carpenter and John Davidson, sexologist Havelock Ellis, and early socialist Edward R. Pease. The notion of ‘new life’ is significant in Lawrence’s work. At the time of the Lawrences’ world tour, Fabian members included Sidney and Beatrice Webb, George Bernard Shaw, H. G. Wells, Annie Besant, Graham Wallas, Charles Marson, Sydney Olivier, Oliver Lodge, Ramsay MacDonald, Emmeline Pankhurst, and, briefly before resigning, Bertrand Russell. The only unifying message across such a diverse group is the developing education of the humanities, the arts, and the social science, against a reductively materialist and ‘unscientific’ science of the age (‘the grossly unphilosophical’). True democracy was quietly reformist, compatibilist, and for all humanity, and not ‘a mob’.

Like Somers, the reader is enticed to a hatred for the mob of ‘little people’ whose fear of the unknown brings them into the stupid arrogance of anti-intellectualism. Lawrence read deeply as he wrote, and his books engaged the literature of the age. The novel speaks to gross failings in mob psychology, the mass movements of fascism and communism. Capitalism with its commercialism also comes under critical examination, for economic systems work between the elites and the mob or masses of ‘little people’. Much of that was capture critically well, thirty years later, in the (American) Eric Hoffer’s The True Believer: Thoughts on the Nature of Mass Movements (1951). The alternative to the historiography of gradual reform is a cyclical view of history where mass movements kill the thing it loves. Like the phoenix, each polemicist fails to learn the histories and deliberately burns itself out, leaving questionable institutes of religion and their socio-political institutions. Fanatically, zealots and martyrs, like St. Paul (Saul) of Tarsus, are resurrected souls where the conversion and their version of the institution has to be challenged. Whereas the oral tradition for the Nazarene speaks of a Jesus who wished to disregard the mob for a small band of followers. The Christian religion made Jesus’ call to follow him a mass movement in a false appeal to the mob.

The challenge of the Industrial Workers of the World (“Wobblies”, IWW) is a backdrop to novel’s concerns for actualising revolution in places like Australia and the United States.[iv] There was also a crossover in syndicalism (owners being the producers, more than the industrial producers to other sectors of the economy) and this was represented in the General Confederation of Labour.[v] The political context for New South Wales in 1922 was the NSW Labor conference in June, after the loss in the March election to the conservatives.[vi] The uproar came in the clash between Fabian-Reformed Labor and the revolutionary IWW grouping of the Party. The revolutionary side won out with bolshevism declared the Party’s fixed objective. This contrast to the calmer transference into state socialism under the Queensland Labor administration (T. J. Ryan and Ted Theodore). Queensland’s advantage in the less hostile passage was that the Labor’s agendas, to a measure, aligned with the conservatives’ agricultural priorities which became known as an agrarian socialism. It was celebrated as the ideals of Steele Rudd’s On Our Selection series (rag novels and radio broadcasts) – socialist cooperatives of the small plot Nationalist landholders, and not the large pastoral station owners from New South Wales. In the end, the ideological distance between the proto-fascists and the militant IWW was small, and hung on the different priorities between agriculture and heavy industries. In the Nationalist-Country Party regime of Joh Bjelke-Petersen (1968-1987) there was no distance, and the different priorities were made one in the lying or false rhetoric: the degradation of the landscape (including the seascape, primary the Great Barrier Reef).

[i] EN. 233:12

[ii] EN. 247:27

[iii] EN. 112:13

[iv] EN. 90:15

[v] EN.196:16

[vi] EN. 160:7; 304:22; 307:31

Image: Sydney Harbour Staging of Kangaroo (1923). See List of Site Markers above.

The theme of Humanism (‘the global perspective’) and National Culture (‘the Australian perspective’) are quietly made. The references to humanism are subtle in the novel, but is clearly pronounced in the reference to Erasmus of Rotterdam.[i] The references to the Rights of Man also speak to this tradition.[ii] The novel’s reference to “Homo sum!”[iii] was well expressed by the ancient playwright, Terance, in “I reckon nothing human (is) indifferent to me…”. Indifference is a mental state of our zeitgeist. Somers’s claims for indifference and not caring speaks to the problem, a twisted British stoicism where passion is sucked out of any life. Jack’s criticism of Somers’s caution seems to draw from Somers’s stoicism.

More prominent is the theme of Sociobiology (ecology and biogeography, the writings of Wilfred Trotter, Louis Berman, and later E. O. Wilson) and its opposition in Personality-Character (Personalism). Lawrence’s Kangaroo can be said to among the several post-war explorations to attempt an explanation for ‘the great event’, the global human tragedy. To find answers Lawrence read Wilfred Trotter’s Instincts of the Herd in Peace and War (1916). Lawrence disagreed with Trotter’s overall sociobiological perspective, but he drew some important insights. In the social psychology, used by Lawrence, we have the idea of passionate revenge.[iv] It is a Nietzschean herd instinct, the will-to-live, and the will-to-power.[v] The problem is that it gets caught, again, in a cyclical historiography with never-ending wars, and not Kant’s perpetual peace.

The basic idea of personality and character mechanically driven by the body’s chemistry was found in Louis Berman’s The Glands Regulating Personality (1921).[vi] It offers a particular view of human nature which is instinctive and opposed to human reason.[vii] It is captured in Kangaroo’s quip on Thomas Hardy’s Blind Fate. Berman also introduced the idea of Kangaroo’s repulsion to careerist ‘ants’.[viii] E. O. Wilson’s Sociobiology: The New Synthesis (1975) and The Ants (1991) developed this early twentieth century ideological thinking, and as psychology it comes too short in knowledge. The novel’s reference to this thinking was the ’tragedy of righteousness’, with righteous heroes leading men (and women) astray in machine-like regimes of life-sucking stupidity, a chemical-induced unthinking or non-critical obedience to the leader.[ix] More often than not it is the sexual chemical drive, but it can be also the stoic, cold-fish, uncaring, personality.

The editors of the Cambridge Edition argue that Lawrence’s works are strongly exploratory of the effects of geographical locations on character”.[xi] Lawrence’s essay, ‘The Spirit of Place’ captures the basic proposition that while Lawrence is drawn to confirm something of the Sociobiology – the connection between landscape and persons – it is not reductive but emergent, coming from the literary side of personality, a consciousness which is not mechanically chemistry and physics. The Australian mechanical view, unfortunately, became far too seeded into the culture.[xii]

[i] EN. 281:26

[ii] EN. 276:27

[iii] EN. 125:37

[iv] EN. 260:2; 264:37

[v] EN. 294:20; 295:12

[vi] EN. 138:21

[vii] EN. 263:8

[viii] EN. 149:26

[ix] EN. 297:1

[xi] EN. 15:36

[xii] EN. 40:32; 188:11

Image: Sydney North Staging of Kangaroo (1923). See List of Site Markers above.

KANGAROO. REVIEW COMMENT 3: LANDSCAPES OF BELIEF-DOUBT AND PERSONS-NATIONS (WHAT IS A FEDERATION?)

The image of a ‘dark God’ and the ideological themes leads to a final comment, a coming together in the strange conflations of Nietzsche, Freud, and Jung, in British Christian thought, and the Australian landscape. It is the landscape that brings both Richard and Harriett Somers to the love of Australia. Richard is initially put off by Australian personality, variously described or framed in terms in ‘consciousness’ from Nietzsche, Freud, and Jung, and of Process philosophy/theology (Alfred North Whitehead). There is a sense that Somers’s references to the ‘dark God’ arises from Cornish or Celtic paganism, but it has been Christianised coming to the monism of a God-in-process with ‘mankind’ (humanity masculinely conceived at the time).[i] Here there is a terrifying contradiction in thinking (or be it paradox?). The individual is to be sacrificed for the common good, and the individual is not to be sacrificed for noble principle. The idea of sacrifice runs through both paganism and world religion, but its application is never straightforward.[ii] Who gets sacrificed and how it differs? Martyrdom adds another layer to the problem.

To understand the impact of the concepts, sacrifice and martyrdom, in social philosophy, the scoping has to be wide to also include scepticism and stoicism.[iii] Scepticism creates the disconnect with the Hebraic understanding of ‘knowledge’. Stoicism keeps killing any possibility for reform in its ‘calmness’ and disconnect to the outside world to which the passive meditator has no control. Hence, there is no necessary urgency for action, nor willingness to take the risk with the ‘dark God.’ “Fate leads the willing man,” but the fatalism of stoicism is too often egotism, the agenda of the State or the Community shaped in the ad hoc agenda of the leader, the Emperor, the dictator, and the individual reader.

James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough: A Study in Comparative Religion (1890) was the work that shaped the thinking of the times for “the nature and historical relations of magic and religion”.[iv] The idea of staging from a magical world to a religious one, draws from Hegel’s Lectures on the Philosophy of Religion (1832) which Frazer applied as an armchair anthropology. Today the work is greatly criticised by the shortcomings in the Hegelian historiography – that each stage of world history (triad) is a clean break from the past; hence, magic thinking does not assumingly appear in ‘religion’ – and the anthropology removed from field studies. Nevertheless, it greatly shaped the works of Nietzsche, Lawrence, Freud, and Jung. Frazer’s account of ritual prostitution and the female sacred sex workers is particularly important here.[v] Such sex workers, it is argued, is not merely instrumental but is worship, celebration, of the divine. It is a masculinised perspective, no doubt, and can infer feminine subservience and slavery.

If prostitution could be fully democratised and socialised (fully feminine, as well as masculine), as is the intent of today’s regulated industry, perhaps, you would have a full expression of life, something to be worship or at least celebrated. This was suggested by Somers’s suspicion of the Calcott marriage, the liberty provided by the ‘dark-God’. There is something of Freud’s father-image which works against this liberty. The Freudian metaphors abound in Somers’s ‘dark God’.[vi] Lawrence adds the mother-image and sister-image in his wider work, and it has a double edge.[vii] On one hand, mother insists that you (male) stop playing with your ‘willy’ and the sanctity of womanhood is preserved. On the other hand, full sisterhood is a voluntary openness to flirtatiousness and promiscuity. The phallic symbols were just below, near the surface, and the masculine literary works needs to balance out with feminine biology and the ‘woman’s works’. Better still would be the gendered merging in the sexual activity. The late 1960s literature and rock music, extending into the late 1970s, integrated so much of D.H. Lawrence’s Freudian themes, into the sexual revolution, often with a gendered sense of fear.[viii] The Women’s Liberation movement – no less a part of the sexual revolution – and the rise of the reactionary ‘Moral Majority’ brought a pulling back in the 1980s pop culture, however, the success of the sexual revolution killed itself, as well, in the excesses and abuses.

[i] EN. 142:39

[ii] EN.285:32

[iii] EN. 112:27

[iv] EN. 283:15

[v] EN. 33:15

[vi] EN. 172:40

[vii] EN. 96:27

[viii] “Mother, do you think they’ll try to break my balls? – Pink Floyd, ‘Mother’.

Image: The Thirroul Staging of Kangaroo (1923). See List of Site Markers above.

Psychology generally suggests that belief systems in origins and maintenance is personal. Somers is disgusted at first by the absolute equalitarianism of the Australian person, but he warms to its unpretentiousness, something that he remembers from the love of the Cornish folk.[i] Harriet is slightly put off by the unpretentiousness and the ingrained-ness of Australian casual companionship. Nevertheless, the bitter memories of wartime British authoritarianism[ii] for both Richard and Harriett Somers meant the Australian casual disregard towards authority and militarism is a ‘saving’ relief. It is also a reminder of similar attitudes, or perceived attitudes, among the Cornish, and, for that matter, among the Welsh, Scots, some Irish folk, and anyone except the English. The critical point of the novel, which perhaps escaped the Englishman Lawrence, is that he only partially captured the “Australian characteristic”, the attitudes or worldview of some Australians.

Equally, the racism which the Englishman Lawrence well depicts of the Australians is at most partially captured, even today: the historical attitude to the Japanese,[iii] Pacific Islanders, and the White Australia Policy.[iv] The unscientific (Nietzsche’s critique), but the nevertheless biological (Bismarck) obsession, was in ‘blood’, ‘blood and iron’. This combined with Australia’s positioning (landscape and seascape) of the tropic Pacific, which would ‘thin blood’.[v] In tropic Queensland we had Sir Raphael West (Ray) Cilento in this era, espousing intemperate thinking. Crossing over into racism, but with its own conceptual bearing, there is also antisemitism, and the Protestant hatred of Irish folk.[vi] Ethnocentrism is a soft racism. It continues to make ‘others’ outsiders from the favoured ethnic perspective. It is the problematic concept of there being a nation’s culture or personality (archetypes). This type of early twentieth century Sociobiology has been shown to be ‘unscientific’ (Nietzsche), a false and outdated model.

Australian always differed in their ethnic (ethos) orientation. Some were Irish-Australians. Other Australians were always British-Australians, and was beholden to that military order. It was for this reason that Somers could never love the militarist Cooley, and could never settle well with the forever-obedient Jack Calcott. Nevertheless, the novel is a global conversation with 1920s Australia. The conversation goes two-ways. The Neighbours, an archetypal image of the television series, Jack and Vicky Calcott, are as curious about Richard and Harriett Somers as they are about them. Jack has high hopes that Richard would come in with Kangaroo and the Digger Club movement, but he is cautious of Harriett and her possessiveness of Richard, as Harriett is cautious of Jack and his violent treatment of Vicky. Vicky is infatuated with Richard, or at least Richard thinks so, and it might be that Vicky is simply fascinated by Richard’s gentleman-ness. Vicky finds in Harriett a close feminine companionship, but where Harriett is cautious, and Vicky casually ignores cultural and class divides. Jack’s brother-in-law, ‘Jaz’, or William James Trewhella is perhaps the most philosophical of the Australian characters. With a little of Marx in character, he is a Nietzschean figure.[vii] Furthermore, with the formal name, ‘William James’, it is undoubtedly a signal to the American philosopher of that name, and his ‘Will to Belief’ thesis. Jaz wants both ways, to have (advocate the proposition) and eat (the skepticism thereof) the philosophy cake. He is in with both the proto-fascist and the quasi-Soviet aims, thinking, perhaps, when the latter revolution comes, the Kangaroo will hop in to provide what is needed to keep social change together.[viii] However, when the Sydney melee breaks out, Jaz takes the noble and philosophical way out. He retreats to the quiet place of dialogue and discussion, away from the violence, and in the process saves Somers from himself. Somers’s articulates the salvation of dialogue in the references to ‘the call and the answer’ and the Beatitudes (oral tradition of Jesus, a voice in the wilderness requiring an answer).[ix]

There is then both overlap and distinction in the Australian landscape of personality. This then brings us to consider the description of the Australian physical landscape in the novel, and the disconnectedness in the environment of the 1920s and today with landscape degradation and climate change happening, and happening faster than before. The most uplifting parts of the novel are the description of the landscape and seascape, and central to that are flora and fauna. The end of the novel, the last few pages, connects the message of the landscape with that of humanity. Australia is the “chief environment of man”. The proper study of mankind is not man, though, but persons in the environment. The central weakness of the novel are references to aboriginality. At least Lawrence did not speak of a “disappearing race”; the problem, though, was the absence of such persons and a misunderstanding of indigeneity. On a positive side, there was something of the ‘global indigeneity’ with memories of the Flora and Fauna of Cornwall, and the Australian descriptions (Flora and Fauna), although that had alien perspective. A new place is always judged from the place whence they came. This is not sufficient today and it does call us to the Uluru Statement from the Heart. Furthermore, the novel ends with a fictional account of the unusual-but-actual sub-tropic cyclone of 21-8 July 1922, and linking it to the China Sea. The cyclonic racism is fiction, a great falsehood for Australians. Cyclones are southern hemisphere bounded, and a winter cyclone is almost unheard of.[xi] The danger was never in the China Sea, but in our inactive calm or polemically passionate storms of judgements at home.

[i] EN. 217:11

[ii] EN.212:2; 212:15; 212:19; 213: 38; 235:35; 247:29

[iii] EN. 89:40

[iv] EN. 90:7

[v] EN. 145:12

[vi] EN. 104:3; 107:40; 110:33

[vii] EN. 201:12; 206:24

[viii] EN. 94:19

[ix] EN. 267:22; 267:27; 267:36

[xi] EN. 349:25

Image: Frieda and D.H. From Cover of Michael Squires, D. H. Lawrence and Frieda: A Portrait of Love and Loyalty (2008).

What would the Somers make of America, on the other side of the Pacific Ocean, the new country where the Somers were headed at the end of the novel? The metaphor of the Pacific Ocean is the key message between the novel and what lied beyond. The name which refers to calm and peace masks the brutal histories of colonialism. The Pacific might speak more to Eastern Australia, but the concept of Indo-Pacific indicates the same history for the Indian Ocean. We all in this together, as Australians, including our Western Australian cousins (‘black, coloured, white’). The era of the 1920s was not only the time of fascism, communism, and racism, it was the rise of the anti-colonial movements. Surely, this is an inverted message from both the (crest symbols) Kangaroo (ethnic NSW) and ‘Emu’ (ethnic VIC and QLD), and Lawrence’s view of Australian colonialism was only in the white experience. It was a problem that the denunciation of the Kangaroo and ‘Emu’ of the historical and continuing ‘slave-labour’ had too little to say about the majority of slaves and actual life lived (persons).

The ‘Emu’ of the novel is a reference to the Victorian equivalent of Kangaroo as the New South Wales military leader of the Digger Clubs and Maggie Squads. It suggested that ‘Emu’ is modelled on Sir John Monash, also Jewish and a military outsider from the conventional establishment.[i] The suggested model for Benjamin Cooley, Major General Charles Rosenthal (who is not Jewish), is too removed from Lawrence’s composite character. Along with the affairs of the New South Labour Conference, it seems historically deliberate to take the militant public discourse of New South Wales and Victoria as the full scoping of the novel. In hindsight, it again marginalises Geoffrey Bolton’s Outer States. The 1992 Boyer Lecture of Western Australian historian Geoffrey Bolton, “A View From the Edge: An Australian Stocktaking (history)”, is a message that the bean-counters in the Sydney-Canberra-Melbourne triangle would like to have every Australian forget, to save embarrassment to their grossly poor policies and policy-formation which had greatly harmed the actuality of the federation. Lawrence would have been ‘in the dark’ on this early chapter of the ever-continuing problem of Federation. The Australian Capital Territory (Canberra, the capital) had been poorly conceptualised when, in 1904, an area around Dalgety was first selected. The New South Wales government refused to cede the required territory and the matter was not decided until Yass-Canberra region was chosen in 1908, a site was closer to Sydney. The novel reference to ‘Canberra House’ in Sydney City depicts the political arrogance – one fuelled by the late nineteenth century rivalry between Sydney and Melbourne – of the State that declared itself as “Premier” of the Commonwealth.

It has put the rest of the country off, and the Victorian-New South Wales rivalry is matched by the “Cane Toads” (Queensland) and “Cockroaches” (New South Wales). The friendly ‘football’ (State of Origin series, an annual best-of-three rugby league series) is a populist mask to serious policy failure in the federation – better to have the hoi polloí blinded by ‘bread and circuses’; contented stomachs and mindless entertainment. Lawrence would have known nothing about the corrupting influences upon the actuality of the federation in 1922. Western Australia, Freida and D.H.’s first port of the call in the country, nearly remained a separate country on a shared continent in 1899-1902, and its distance from the eastern states has always meant difficulty to keep the country together conceptually in the minds of Australians. It is no accident that the “An Australian Stocktaking” was delivered by a Western Australian historian. The tone-deaf political and bureaucratic idiots have continued to ignore the message of 1992. The novel’s talk of secret armies and revolutions was the danger the country faced if it could not keep the hoi polloí in a blinding illusion about the federation. It is likely that if a proto-fascist or a quasi-Soviet revolution did occur in 1920s Australia, the federation would have been destroyed and the Commonwealth would have fallen apart. In 1922 the Canberra Capital was still being built and it was not until 1927 that a truly independent Federal Parliament was established, with the previous and temporary parliament in Melbourne. You would have had separated Nation-States of (possibly, and at least) a Tory-Liberal coalition Victoria, Socialist-Labor Queensland, and an unsettled New South Wales with a choice between a Premier Lang-radical Labor and a Governor Game-Conservative-Monarchical regime, depending on what militia defeated what militia. This is based on the actual trajectory which can now be read professionally in hindsight. The same politics was delivered without revolution and violence. In a small part Australians can be thankful but the cost has been the continuing ineffectiveness of the federation, in providing any sense that we are one country, one nation, and in any ‘real’ sense a single culture or a single people. This is one of the great examinations that Lawrences draws in references to Indian nationalism[ii] and Irish nationalism.

The underlying problem has recently become more apparent in the face of the Uluru Statement from the Heart (2017) – the best delivery of a unified indigenous voice and the final defeat of the ‘disappearing Aboriginal’ narrative and the reversed exporting of the Pacific Islander (Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples; “we are part of the Pacific world” but there is still historical refusal to recognise the harm against persons of Pacific immigration in the White Australia Policy and beyond). How do we find one voice in diversity?

How do we live together in a degraded and degrading landscape? The only way forward is to be able to map the historic landscape and then to act between equality and liberty, and not making an excuse for one to destroy the other. It involves compromise, and it can be understood in compatibilist philosophy, the highest achievement in dialogue and discourse. D.H. Lawrence’s Kangaroo (The Cambridge Edition) delivers much in this part of the seamless world.

[i] EN. 186:4

[ii] EN. 90:28

Image: Frieda Freiin von Richthofen in 1901 (August 11 1879 – August 11 1956, later Lawrence, from March 1912 until D.H. death in March 1930). Child unknown. Wikipedia.

*****

Music for the reading, Cognition: Both thinking and feeling as one.

Learning To Fly

Pink Floyd

Into the distance, a ribbon of black

Stretched to the point of no turning back

A flight of fancy on a wind swept field

Standing alone my senses reeled

A fatal attraction is holding me fast

How can I escape this irresistible grasp?

Can’t keep my eyes from the circling sky

Tongue-tied and twisted, just an earth-bound misfit, I

Ice is forming on the tips of my wings

Unheeded warnings, I thought I thought of everything

No navigator to find my way home

Unladened, empty and turned to stone

A soul in tension that’s learning to fly

Condition grounded but determined to try

Can’t keep my eyes from the circling skies

Tongue-tied and twisted, just an earth-bound misfit, I

Friction lock, set

Mixtures, rich

Propellers, fully forward

Flaps, set – 10 degrees

Engine gauges and suction, check

Above the planet on a wing and a prayer

My grubby halo, a vapor trail in the empty air

Across the clouds I see my shadow fly

Out of the corner of my watering eye

A dream unthreatened by the morning light

Could blow this soul right through the roof of the night

There’s no sensation to compare with this

Suspended animation, a state of bliss

Can’t keep my mind from the circling sky

Tongue-tied and twisted, just an earth-bound misfit, I

Source: Musixmatch

Songwriters: David Jon Gilmour / Anthony Jon Moore / Jon Carin / Robert Alan Ezrin

Learning To Fly lyrics © Emi April Music Inc., Pink Floyd Music Publisher, Gone Gator Music

*****

Composite Image from Social Media Sources. Relating D.H. and Frieda Lawrence, The Cambridge Edition of ‘Kangaroo’ (1923, 2002), and stills from the YouTube Au online video, Pink Floyd – “Learning to Fly ” PULSE Remastered 2019. Called, as art piece, “Fully Sexed and Knowing Kangaroo”.

The novel ‘Kangaroo’ is flying experience in reading. You’re deported to Australia one hundred years ago, where passions were flying, and the Lawrences were flying across the globe by ship. It was a “A flight of fancy on a wind swept field.” And the reader, Somers (D.H.) and Harriett (Frieda), all are:

Standing alone my senses reeled

A fatal attraction is holding me fast

How can I escape this irresistible grasp?

For the Lawerences, the characters, and the readers:

A soul in tension that’s learning to fly

Condition grounded but determined to try

Can’t keep my eyes from the circling skies

Tongue-tied and twisted, just an earth-bound misfit, I.

And in the novel’s ideological examination:

Ice is forming on the tips of my wings

Unheeded warnings, I thought I thought of everything

No navigator to find my way home

Unladened, empty and turned to stone.

In the landscapes and seascapes:

Above the planet on a wing and a prayer

My grubby halo, a vapor trail in the empty air

Across the clouds I see my shadow fly

Out of the corner of my watering eye

A dream unthreatened by the morning light

Could blow this soul right through the roof of the night.

And in the end (see The Ontological Compass):

There’s no sensation to compare with this

Suspended animation, a state of bliss

Can’t keep my mind from the circling sky

Tongue-tied and twisted, just an earth-bound misfit, I

*****

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- Dear grossly, ethically, corrupted - December 21, 2024

- Thoughts with a Professional History colleague on “Artificial Intelligence” - December 21, 2024

- Stephanie M. Lee on “AI by omission”, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Thursday, December 19, 2024 - December 20, 2024