by Neville Buch | Mar 4, 2024 | Concepts in Educationalist Thought Series, Concepts in Public History for Marketplace Dialogue, Essay for Social Change

“Police” might not be ‘a great’ acronym, but I referring to each person “policing” their own thought. What I am referring to, is not “self-censorship” in the way the libertarians discuss this concept of “self-censorship”. Libertarians get themselves in knots in thinking that “they”, as individuals, must not fail in the cognition of acknowledging each personal thought as valid, and sound, basis on its libertarian valuing. Principles of the Critical Theory field are being referenced here. When libertarians are not critiquing the field in the effort to rescue a libertarian argument (negativity: the attempted negative argument), there is automation in the action between stating the “valid and sound” acknowledgment and the alleged logical-ontological compatibility (positivity; the attempted positive argument). Compatibility [1], valid and sound philosophy ought to be the aim, but there is no automation – as in the alleged claims of “artificial intelligences” – which is valid and sound. There is not one (singular) paradigm at work and, in fact, it is intelligence, philosophically understood, which is the organising principle. It is akin to Aristotle’s view of the Soul as the organising principle. Rationality is abused in the paradigm of hard rationalism. And this is the reason why the rationality is abused, as in the militancy, of acknowledging each personal thought as valid, and sound automatic. Most (but not all) of the libertarian rhetoric are assertions. The rhetoric does not have the elements and dynamics of Jürgen Habermas’ communicative action. Libertarianism is historically a product of several culture–history wars during the 20th century.

Philosophically Ontology Logic Intersect Compatibility Education (POLICE) is a claim as follows: to sufficiently defunct the practice of the culture-history wars, philosophically turn to reading the ontology and logic, and intersect truthful claims as a stance of compatibility, achieved as this being–logically education. Here is a theory in the philosophy and sociology of education.

The philosophy is very applicable in applied educational settings. A few examples can be given. In a discussion of community education, the subject of “A.I. hallucination” was explored: we are not talking about a personal experience of hallucination but the machine as a representational mirror of the human experience. There is a legitimate disassociation here. The machine cannot have any agency. It deliberately “chooses” (metaphor) to misrepresent, in other words, the machine itself is determinate and cannot self-correct, in the exact way that the libertarian falls into the half-life cognition of acknowledging each personal thought as valid, and sound automatic. In the discussion an astute mind stated: “Unfortunately, so many of my Rationality-worshipping colleagues treat ChatGPT like it was an ideal [sic]”. My friend meant to tap “idol” rather than “ideal” but, with many cases of the stupidity of the self-correcting technology, the machine, in total unawareness, appears to be “clever”. The hard rationalist-libertarian-materialist is saying that, “If only we could get rid of our emotions and feelings, we could then be completely rational and logical.” It is an Ideal, and as an ideal it works. BUT ideals cannot work as daily practice. There are impractical ideals, and ideals which can effectively work in the long-run. If this ideal – to become a machine – was worked as daily practice, the individual cognition is deformed. Such a case is nearly impossible, and the question has to be, is it advisable (work of “the ought”)? Dissidents might rebel to this extreme but the ethical question is ought a person evolve into a machine. The question is answered in the compatibility between the “No Harm” principle and the characteristics of a flourishing human being. In our poor reading, though, we are currently going from the ideal to the idol: mindless worship of the machine.

There is difficulty in the idealism of rationality, and what I trying to explain is that the seeds of the difficulty (“little”) started in the philosophy discipline, in the development of a school of thought militantly to what came before and what comes after. The difficulty dramatically increases in the popularism, as fallacies are added upon one another on the sacrificial table of the idol.

The first example, just explained, is the legitimate negative argument. A second example of POLICE is a positive example of three community educational managers, as scholars, putting our joint interest, opportunity and benefit together in exploring overlapping intelligence. It is the philosophical compatibility practice by Dr Neil Peach, Dr Donnell Davis, and Dr Neville Buch. Intelligence matters, and as per Habermas, it is achieved in both as a compassionate community and as a democratic society.

The “socio-community” work of these scholarly-managers, as policing their own thoughts, on the histrio-theorio-politico outline of various movements in thought, shaping a community and a society. The scholars review, in the momentary selection, the linkages in order to better connect with the communal knowledges and ideas. In the other direction, that of the culture-history war, is the ‘efficiency’ cause, with the impetus and momentum for putative ‘progress’ created by the combination of science, technology and commerce. The concept-in-practice of efficiency has steam rolled many dimensions of human agency and thought, and due to the speed and the energy people need to respond to this speed-change, memory is lost and the absence of memory is filled with techno-experiences that flood the human in a sea of ‘what is’ and ‘now’.

The critic of the essay messaging will attempt to conclude that the essay is a case of cognitive dissonance. The dismissive is nonsense, but it will be said by the average citizen and too-smart-ass academics. In the field of psychology, cognitive dissonance is the perception of contradictory information and the mental toll of it. As an action or idea, it is psychologically inconsistent, as a set of claims with the other, people do all in their power to change either the argumentative agenda, stress, or acceptance of the hard stoics’ of “what it is” (resignation or fatalism) so that they become consistent. In this negative argument part of the dismissive, we have a logical misnomer. The argument of the essay has not changed: the argumentative agenda, stress, nor changed the criticism in the acceptance of the hard stoics’ of “what it is” (resignation or fatalism).

In the positive argument of cognitive dissonance, the theory proposes that people seek psychological consistency between their expectations of life and the existential reality of the world. To function by that expectation of existential consistency, people continually reduce their cognitive dissonance in order to align their cognitions (perceptions of the world) with their actions. This is exactly what the essay has achieved as its argument. Only in the positive argument of cognitive dissonance can a claim be made of the essay, not a charge of unethical behaviour.

People who actively avoid situations and information are likely to increase cognitive dissonance – the discomfort from holding contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values, or dealing with new information that conflicts with existing beliefs, ideas, or values. People do not think much about their attitudes, let alone whether they are in conflict. They can come to conclusions as observers without much (or no) emotional or intellectual (cognitive) reflection.

The situation is most likely worse. No one has time to think, and to recognise what is lost….almost no one in the global demography. However, there is a growing (at this stage) non-school grouping who are performing in POLICE. Drs Peach, Davis, and Buch, are showing a better understanding, and a better practice. In this way, it is not only good for a community and a democratic society, but energy and efforts are made towards a more complete and contributory economy.

Acknowledgement of the work of Dr Neil Peach and Dr Donnally Davis in the composition of this teaching essay. Note the links to Wikipedia does not necessarily take you to an article that you intuitively think. Be aware that separate words might be separately linked.

[1] An oppositional system to the negative-positive inclusiveness is “forward compatibility” which destroys the capacity of “history” for the system. There is “backward compatibility” but the transference in these cases filters the understanding of the technology history.

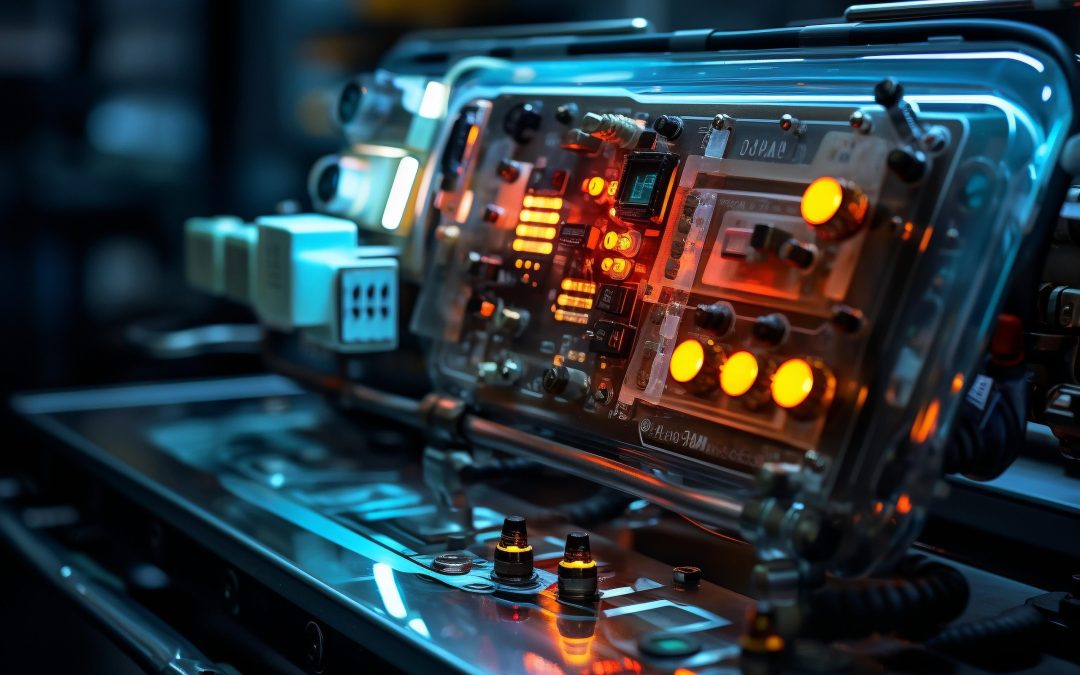

Featured Images: Illustration 301363328 © Artofthew33k | Dreamstime.com

Dreamstime.com Description as the Narrative: “A close-up of a high-tech gadget with glowing lights and buttons, symbolizing the control and manipulation of technology. A sleek and modern device sits in front of us, its smooth surface reflecting the light around it. The camera focuses on one button, which is illuminated by an LED light that gives off a soft glow. The background is dark, emphasizing the contrast between the high-tech gadget and the rest of the world. The device has multiple buttons arranged in a circular pattern, with each button having its own unique function. Some are labeled with symbols or letters, while others have no markings at all. As we zoom in closer, we can see that there is a small screen on the top of the device, displaying information and data. The glowing lights on the buttons create an almost otherworldly effect, as if they were some kind of magical tool for controlling technology. The contrast between the dark background and the bright lights draws our attention to the device itself, making it stand out from everything else around us. Overall, this stock image represents the power and control [over the human] that comes with modern technology. It shows how even something as simple as a button can have a profound impact on our lives, and how we use technology to manipulate and shape the world around us. AI Generated.

by Neville Buch | Jun 7, 2024 | Concepts in Public History for Marketplace Dialogue, Important Public Statement, Intellectual History

“… Last Friday, Salem Media Group announced that it had removed the fabulist film 2,000 Mules from its platform and said it would no longer distribute either the movie or an accompanying book by the right-wing activist and Trump-pardoned felon Dinesh D’Souza. It also issued an apology to Mark Andrews, a Georgia man whom the film had falsely depicted participating in a conspiracy to rig the 2020 election by using so-called mules to stuff ballot drop boxes. After being cleared of any wrongdoing by the Georgia Bureau of Investigation, Andrews filed a defamation lawsuit in 2022 against D’Souza, Salem, and two individuals associated with a group whose analysis heavily influenced the film.”

Ken Bensinger, ‘2,000 Mules’ Producer Apologizes to Man Depicted Committing Election Fraud, The New York Times, May 31, 2024

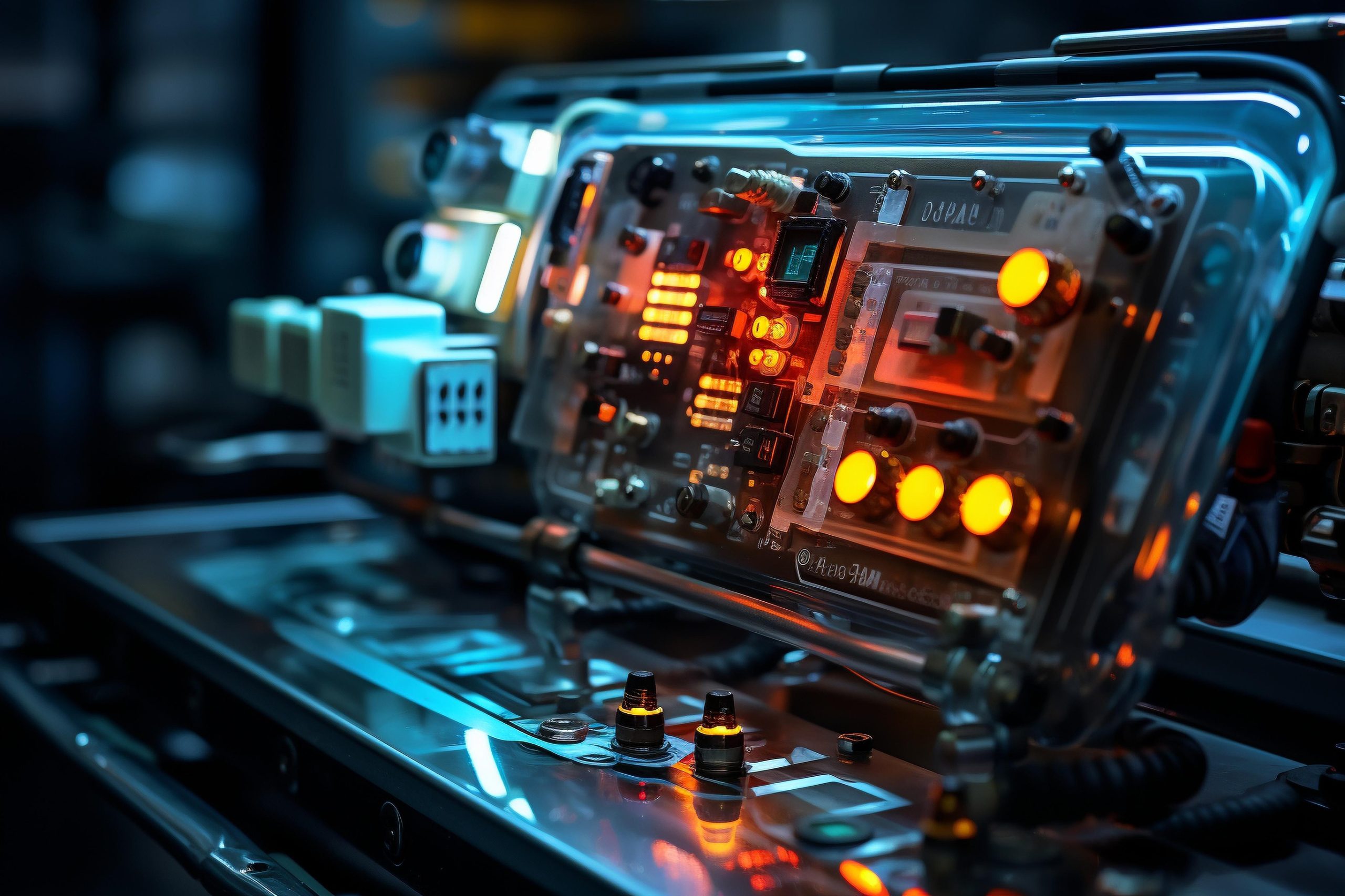

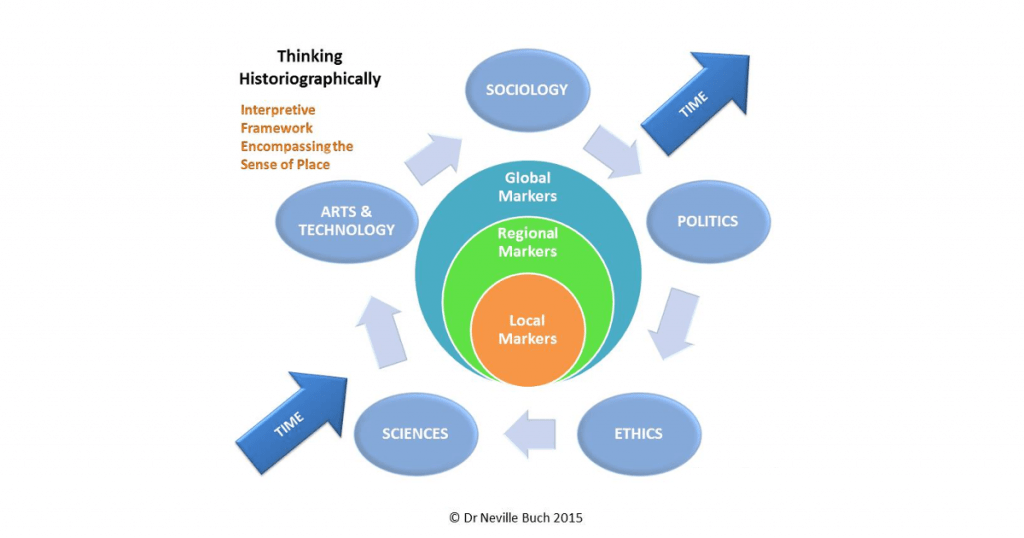

Graph: Thinking Historiographically 1024×538.

History spirals. There’re at least four main steps in the spiraling action.

1. Widely-Believed Falsehood:

Recently, we have seen the widely-believed falsehood in the the fabulist film 2,000 Mules. Films have been a platform of widely-believed falsehood since the beginning of Hollywood at the turn of the 20th century. In the last half century, though, films have become more bluntly politically-charged. The Washington’s Watergate-charged atmosphere of the 1970s, not ceasing from the late 1960s other American political intrigues, made the messaging very blunt. On the Left, was the later Emmy Awards-winner history drama TV movie, KENT STATE, 1970 (2023 Monarch Films). The film dramatization could not be done for a decade, so painful had the event been in American cultural life. The leftwing roots meant a romanticism which did not help to get an accurate historical sense for its present. On the Right, were the American 1970s evangelical apocalyptic movies. On the first uneducated glance, these films may not appear to be politically-charged. However, the pre-millennial message of A Thief in the Night (1972), A Distant Thunder (1978), Image of the Beast (1981), and The Prodigal Planet (1983) brought the themes of the Rapture and the Tribulation, where either politics was portrayed as a-politically irrelevant (itself a politically-charged message) or politics was portrayed as a secular government out to destroy the religion of the devout. The films were alarmist for the political agenda to destroy the leftwing (other) agendas of the late 1960s and 1970s. The falsehood was widely-believed but was always one large section of the society. In the United States it is estimated that supporters of Donald Trump is only one-fourth of the population. It estimated 30 to 35% (90 to 100 million people) are Evangelicals in the United States. Australia is not remotely distant to such widely-believed falsehood. Even as there has been significant resistance to Americanization in Australia, recent militant protests during the short era of the global pandemic shows a sizable section of the Australian population captive to far right narratives.

Ken Alder in an article called, “A Social History of Untruth: Lie Detection and Trust in Twentieth-Century America,” wrote:

…the efforts of twentieth-century American experts to oblige recalcitrant men and women to tell the truth about themselves. How different are these two enterprises [detecting lying and trust]? When Albert Einstein inscribed above his fireplace the motto, ‘‘Nature’s God is subtle, but He is not malicious,’’ he surely acknowledged as a corollary the possibility that people might be malicious, if also sometimes subtle. It is this latter corollary that has inspired the proponents of an American science of lie detection. Their premise is that while a human being may tell a conscious lie, that person’s body will ‘‘honestly’’ betray his or her awareness of this falsehood…(1-2)

2. Accountability:

There is accountability to teachers, mentors, supervisors, and others who guide us through life. Well, at least there once was. Accountability has undergone significantly challenges in the last six decades. On one level it is a perennial theme in “thumbing one’s nose,” not at authority, but each at their own sense of comprehensive responsibilities. Persons always “thumbing one’s nose at authority,” and that is healthy, if it is also not very effective. However, responsibilities that one’s owns is far more than the comfort that is given in the “freedom of speech.” To take responsibility, that is, to be accountable, rewards the person with integrity of being a person. In other words, it is normative mental health. The challenge is understanding “responsibilities that one’s owns.” Central to holding it together is the truth of the knowable and unknowable. The glue of integrity is knowable and it is also unknowable. Contrary to populist bullshitting, epistemology has not destroyed what we might designate as knowledge nor the capacity to know. Any technical epistemic justification, somewhere along the trees of argumentation, would be suffice. So, be accountable, and stop the bullshitting. Still, there are many matters which are unknown, and it is still undecided whether matters will ever be known (so, unknown). The glue chemistry for the unknowable is humility.

Jonathan Gorman in article called, “Historians and Their Duties,” wrote:

We need to specify what ethical responsibility historians, as historians, owe, and to whom. We should distinguish between natural duties and (non-natural) obligations, and recognize that historians’ ethical responsibility is of the latter kind. We can discover this responsibility by using the concept of “accountability“. Historical knowledge is central. Historians’ central ethical responsibility is that they ought to tell the objective truth. This is not a duty shared with everybody, for the right to truth varies with the audience. Being a historian is essentially a matter of searching for historical knowledge as part of a an obligation voluntarily undertaken to give truth to those who have a right to it. On a democratic understanding, people need and are entitled to an objective understanding of the historical processes in which they live. Factual knowledge and judgments of value are both required, whatever philosophical view we might have of the possibility of a principled distinction between them. Historians owe historical truth not only to the living but to the dead. Historians should judge when that is called for, but they should not distort historical facts. The rejection of postmodernism’s moralism does not free historians from moral duties. Historians and moral philosophers alike are able to make dispassionate moral judgments, but those who feel untrained should be educated in moral understanding. We must ensure the moral and social responsibility of historical knowledge. As philosophers of history, we need a rational reconstruction of moral judgments in history to help with this. [added emphasis]

3. Falsehood Retreats:

There are fools who argue that since perception is the mental filter we can never know truth from falsehood. There two basic reasons why this is a bullshit argument. First, perceptionism is not the opposite or disjuncture with Object-ism (not to be confused with Ayn Rand’s Objectivism). There are objects in the world, and we know that there are objects in the world by the fact of perception. It is perception that can tell us whether we have a true object perceived, or whether the ‘object’ is an illusion. Perception can lead to illusion in the mental reflection (i.e. the thought about the thought), thus, we have the falsehood. On the other hand (or in another direction of the brain firing), we can reasons ourselves to the truth from perception. The question is what truth is being established. For each truth proposition is relative to the other, until it networks out into a holism (Willard Van Orman Quine). Now, those who follow Rand “get very hot under the collar” at this point. However, Quine can help us out. He advocated a behaviorist theory of meaning which meant that the distinction between analytic and synthetic statements are defended ambiguously, undermining verificationism, and we have to retreat to behavioural judgements. For most epistemologists with the contemporary fallibilism, Quine’s critique is untroubling. Life, and knowing life, will always be ambiguous. The point is that Rand is very wrong in her Objectivism, we ‘know’ that we do not understand objects directly, otherwise nobody could even talk about perception. Quine helped by demonstrated that in stating ‘truth’ of analytic and synthetic statements we can never completely be there. Indeed, Quine is being inconsistent between his behaviouralist semantics and his scientific holism.

Now, there will be idiots who dismiss the above paragraph because it simply logic and epistemology, and not, as they proclaim, politics, history, or sociology. However, the above paragraph works perfectly well as political philosophy. An argument of falsehood might go like:

- There are those Right/Left persons who are all relative and cannot accept the Object in my politics;

- Such persons are confused in directly “perceiving” the Object;

- Conclusion — “I am right (correct) and they are wrong.”

W. Speed Hill in an article called, “Doctrine and Polity in Hooker’s ‘Laws’,” wrote:

If he is read today at all, Richard Hooker is read as the author of a single work, the massive treatise Of the Laws of Ecclesiastical Polity. Yet his other writings, if one includes Chapters iv-vi of Book vi, the “tract of confession” over which the dispute arose at Hooker’s death, amount to one-quarter of his extant work. Largely unexplored, they reveal the essentially inward bias of his mind, and they set forth, independently of the disciplinarian context of the Laws, the doctrinal assumptions that underlie its defense of established polity. From the perspective of these non-Polity writings, the Laws , for all its length, its wealth of illustrative detail, and meticulous argumentation, is simply an application in extenso of more general principles that Hooker enunciates elsewhere… But to see these doctrinal issues as Hooker himself saw them is to see the arguments of the Laws in a perspective nearer to Hooker’s own, one less colored by the pervasively controversial bias of his lay collaborators…[added emphasis]

4. Historical Forgetfulness:

In “Buckley’s Chance, Cultural Thinking of Trumpism, and History” I have stated:

The mob’s logic — all minority positions — is x = zero (liberalism offers nothing for me personally), so non-x (fascist thinking). Forgive my poor logic writing here. The better logicians are welcome to formulate the mathematical language in its better expression. But the point is historiographical solid. Historical forgetfulness leads a population into the spiral history theory of stupidity.

What is needed? Conversations and agreements to the compatibilism, as I have explained in my short piece, Finding Peace from the Culture-History War: A Historiographical Message for the Times.

My concern is that we have Buckley’s Chance to turn matters around, and we are trap on the spiral of eternal return (see links above, “the spiral history theory of stupidity”; each word here has a different link in the phrase, and the same with other phrasing above).

What humans need and want of life is Peace, if also Survival and Flourishing. This is what we have to keep foremost to Mind.

The last stage of the spiral is historical forgetfulness. And the cycle of the spiral begins again in the historical memory which is not re-discovery, as direct realism, but the shades of ideas brought back to a new life.

David Michael Kleinberg-Levin in an article called, “The Court of Justice: Heidegger’s Reflections on Anaximander,” wrote:

… In his commentary, Heidegger draws on Nietzsche’s thoughts about justice, the will to power, and nihilism to formulate an interpretation of the fragment that connects it to the epochal history and destiny of being. This “ontological” interpretation, constructed in a compelling reading of the history of philosophy, requires that Heidegger first address the historicism and “onto logical forgetfulness” prevailing in historical consciousness and historiography, in order to begin thinking towards the possibility of another epoch of being, releasing us from the injustice that is inherent in the ontology that rules in the present historical dispensation. Although Heidegger avoids moral prescription, he cannot avoid critical entanglement in the moral-juridical sense of justice, despite his claims and protestations, since, as his own account of the fragment implies, justice and ontology must be inseparable. Reading Heidegger’s commentary in relation to Benjamin’s philosophy of history, I argue that Heidegger’s reflections on justice suggest a narrative of tragic hope that resembles Benjamins configuration of justice in his reading of the Baroque mourning-play, where the hopelessly fragmented and imperiled image of justice is revealed as emerging from a Leidensgeschichte fatefully bound up in the continuum of a Schuldgeschichte [added emphasis]

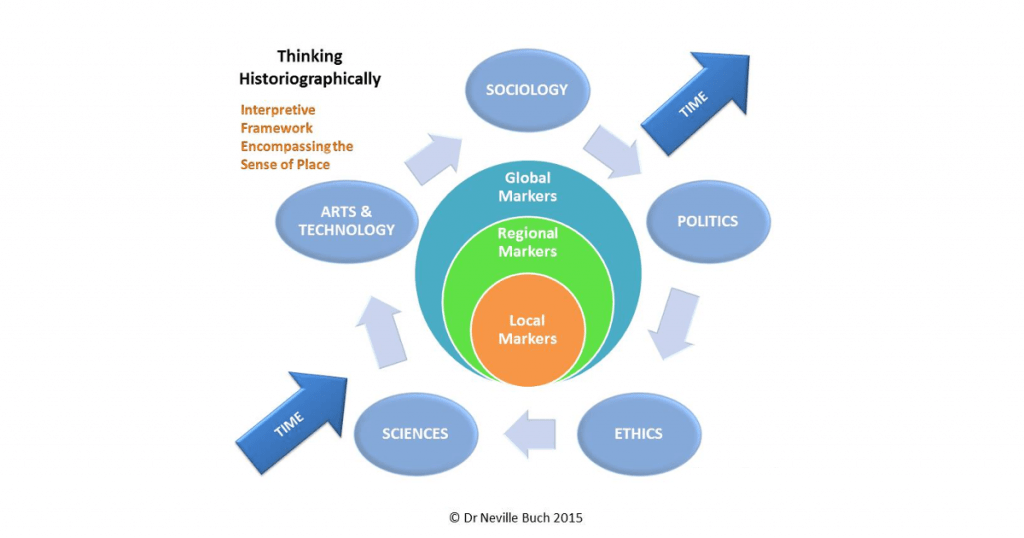

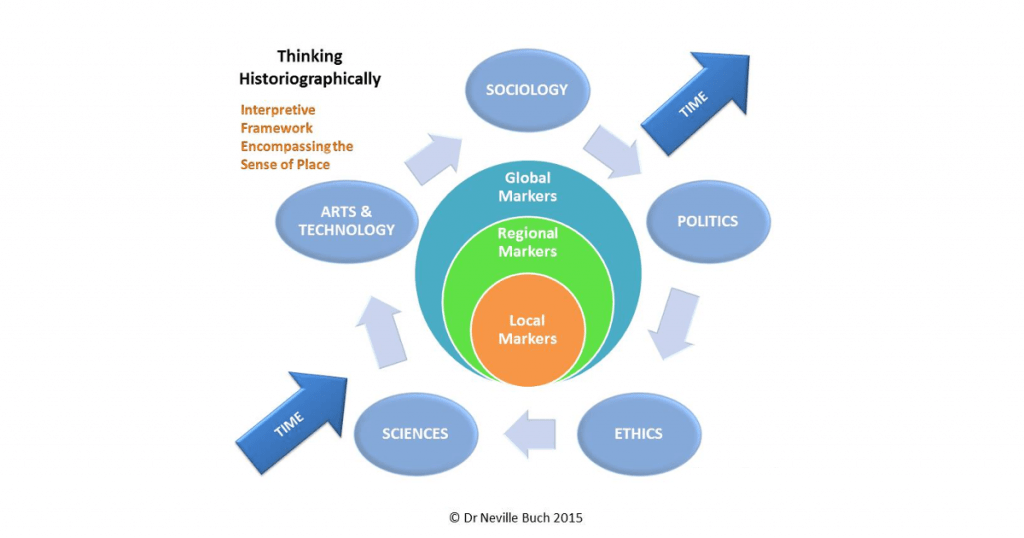

Conclusion in Australian Intellectual Historiography

On the eternal returns, as an intellectual historian examining the previous era of 1945-1985, we find, in the revaluations (Nietzsche’s perceptionism reconsidered), that Manning Clark and Donald Horne, from the two ends of the political spectrum, had already given us four stages of spiral historiography.

See, Progress and Popular Thinking in the United States & Australia 1945-2020, and, Geo-Political Debate in Australia: An American-Australian Relational (Intellectual-Cultural) Reading.

How stupid we are in not paying attention to the intellectual histories which just spiral around, a little forward, and a little retreat.

REFERENCES

Alder, K. (2002). A Social History of Untruth: Lie Detection and Trust in Twentieth-Century America. Representations, 80(1), 1–33. https://doi.org/10.1525/rep.2002.80.1.1

Gorman, J. (2004). Historians and Their Duties. History and Theory, 43(4), 103–117. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3590638

Hill, W. S. (1972). Doctrine and Polity in Hooker’s “Laws.” English Literary Renaissance, 2(2), 173–193. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43446757

Kleinberg-Levin, D. M. (2007). The Court of Justice: Heidegger’s Reflections on Anaximander. Research in Phenomenology, 37(3), 385–416. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24660579

by Neville Buch | Dec 17, 2018 | What Time Is It?

Anniversaries and commemorations come and go daily. Most of us, even the best historians, miss most occasions. If we think of history as events then we are faced with a continually showering in the grains of sand. Nevertheless, we do pick out certain patterns in the remembrance of historical dates. The blog here reminds us of some dates where the local, state, national, and global perspectives entwine.

On 17, Sunday December 1843, Charles Dickens’s novella A Christmas Carol is first published in London, England. Released on December 19, it sells out by Christmas Eve.

On 17, Tuesday December 1918, The Darwin Rebellion takes place, with 1,000 demonstrators demanding the resignation of the Administrator of the Northern Territory, John A. Gilruth.

On 17, Tuesday December 1918, Darwin Rebellion in Australia: Disaffected workers march on Government House, Darwin, demanding the resignation of the Administrator of the Northern Territory, John A. Gilruth.

On 17, Tuesday December 1918, Dusty Anderson born, American actress, model

On 17, Friday December 1943, Ron Geesin born, British musician and songwriter (Pink Floyd)

On 17, Friday December 1943, Rick Nolan born, American politician

On 17, Tuesday December 1968, In England, Mary Bell, aged 11, is found guilty of murdering two small boys and sentenced to life in detention, but is later released from prison in 1980 and granted anonymity.

On 17, Tuesday December 1968, Paul Tracy born, Canadian race car driver

On 17, Sunday December 1978, Manny Pacquiao born, Filipino boxer and politician

On 17, Sunday December 1978, Chase Utley born, American baseball player

On 17, Saturday December 1988, David Rudisha born, Kenyan middle-distance runner

On 17, Saturday December 1988, Rin Takanashi born, Japanese film and television actress

On 17, Saturday December 1988, Jerry Hopper died, American film and television director (b. 1907)

On 17, Friday December 1993, Ralph Willis replaces John Dawkins as Federal Treasurer after John Dawkins goes to the backbench, announcing his imminent retirement.

On 17, Friday December 1993, Kiersey Clemons born, American actress and singer

On 17, Friday December 1993, Janet Margolin died, American actress (b. 1943)

On 17, Thursday December 1998, Martin Ødegaard born, Norwegian footballer

On 17, Thursday December 1998, Jasmine Armfield born, English actress

On 17, Thursday December 1998, Claudia Benton died, Peruvian-born child psychologist (b. 1959)

On 17, Tuesday December 2013, Cricket: Australia regains The Ashes for the first time in seven years, after winning the first three tests of the 2013–14 Ashes series.

Other On This Day days in history

by Neville Buch | Apr 27, 2024 | Important Public Statement, Intellectual History, What Is History Meaning?, what-time-is-it

An excellent piece, Christofer:

“At issue between these two interpretive poles is the basic presumption of applied social science: to what extent can the recognition of recurring patterns translate into effective political policy? Yet, Thucydides was not writing social science as we know it. To the extent that his text articulated anything like fundamental laws of political behaviour, it did so through exemplary instances and carefully curated parallelisms.”

The author is Mark Fisher is assistant professor of government at Georgetown University in Washington, DC. His research focuses on the history of democratic thought and, especially, on early attempts to understand and theorise Athenian democracy. Published in Aeon

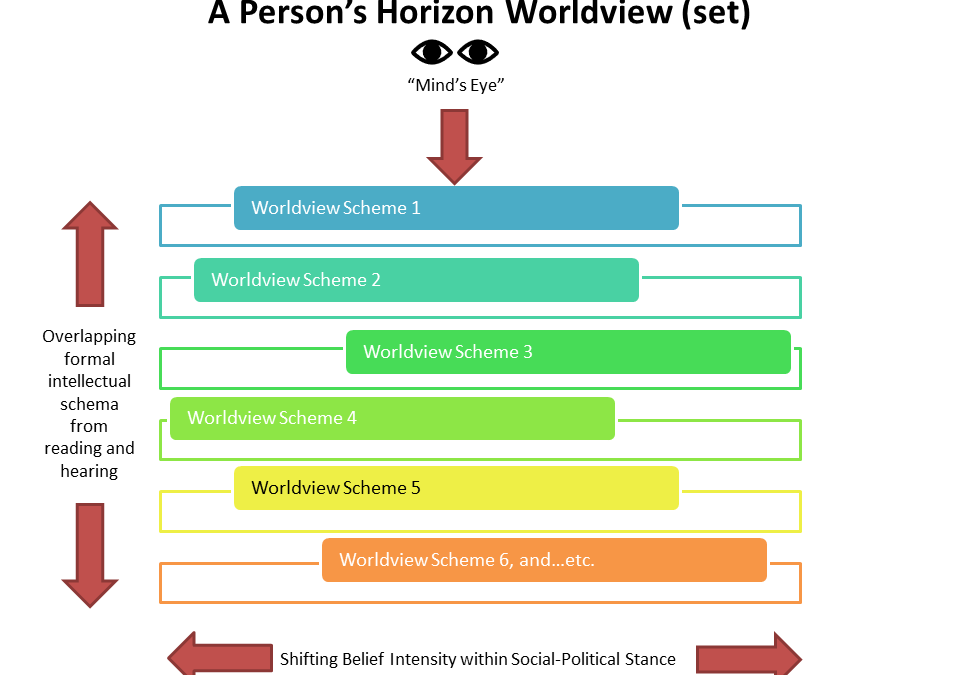

The outlook on parallelism confirms the general ethos of global historians. The population is too generally captivated by presentism. Presentism, which is the reading from the present has a correct and incorrect status. Correct, it is, that everyone asks the question from the present. The present is the starting point, even as we might ask what was the actual view at the time past. Our understanding is an amalgamation of outlooks from the past which presents as present. If we remember that, we are safe in truthfulness and holistic meaning.

Incorrect, it is, in the ignorance of the present, that is, we have no idea (or too few ideas) how we are each subject to the personal amalgamation of outlooks from the past which presents as present.

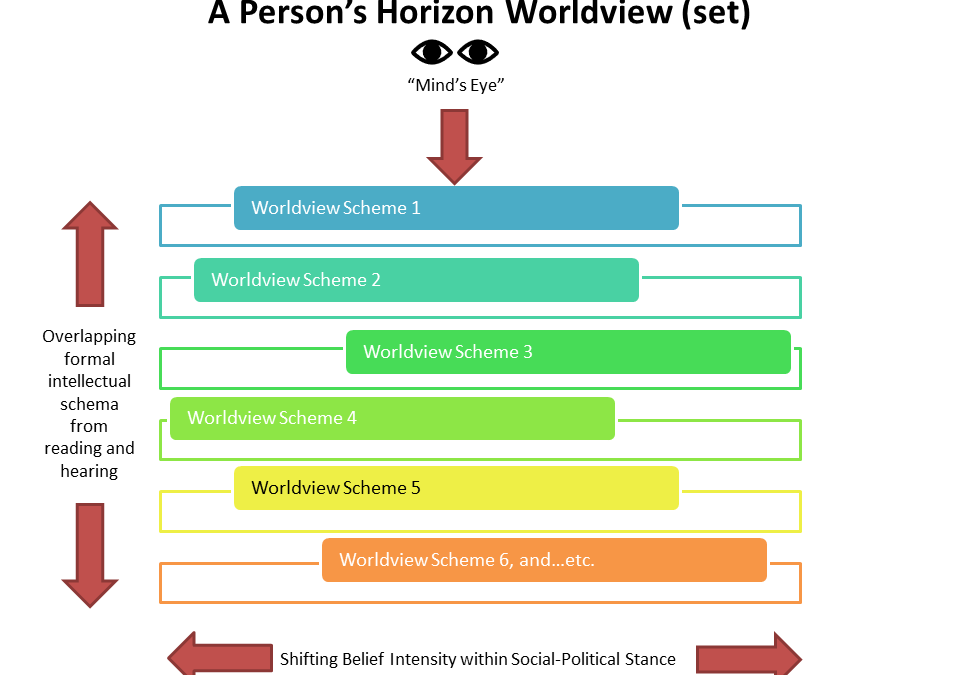

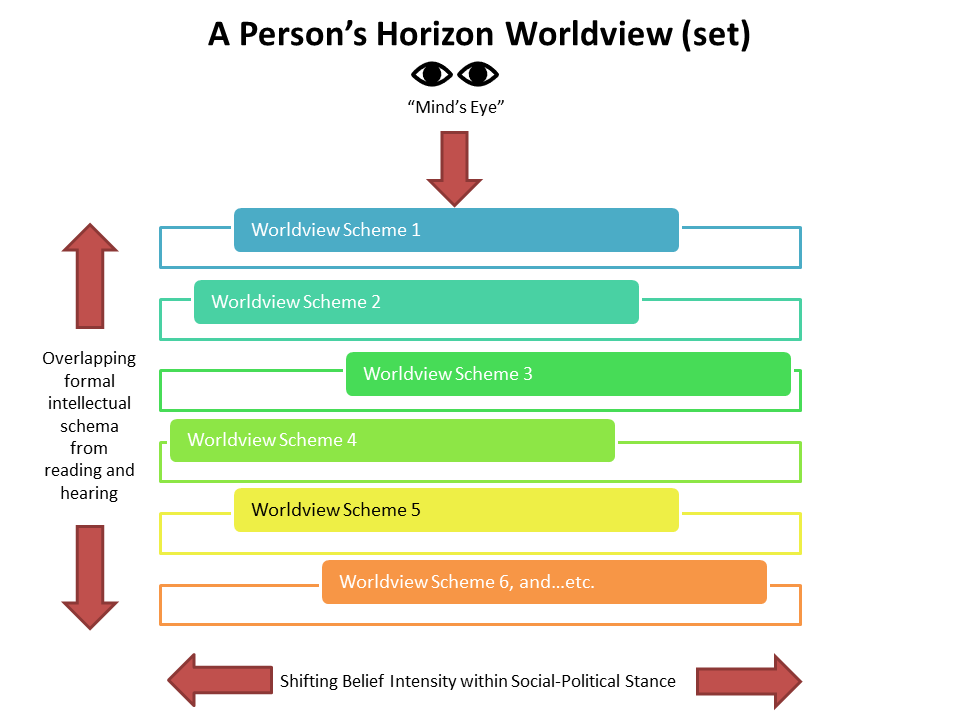

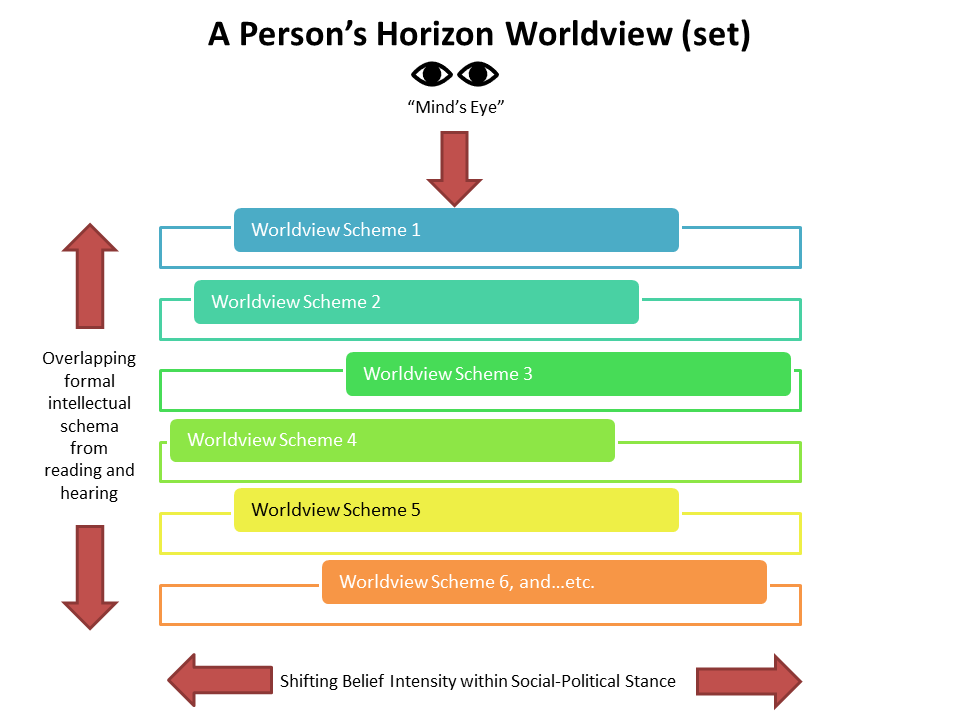

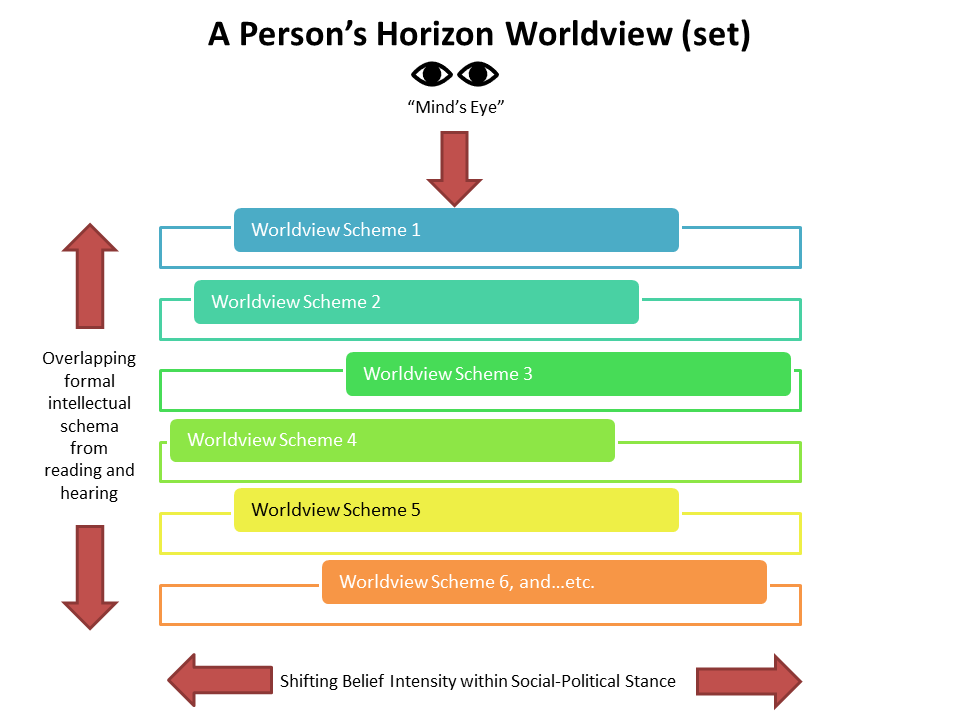

I “hear” with the “mind’s-eye” the politician, or other such political decision-maker saying, “I do not have time nor the funds to investigate history.” What they are really saying is, “do not disturb my view of the past…I need the political space to push my favoured decisions…and historians are only pessimistic-mongers…God damn, Thucydides, Marx, and Nietzsche.” These political thinkers are the ones (not the historians) – if they each do not choose to change – who have no hope.

The best historian can find the hope for the political decision-maker.

Then there is the poor excuse of the political decision-maker, “no, we cannot afford to fund, contract, or employ professional historians.” It is such a poor excuse from professional politicians, that many would not think it worthy of a reply. But an intelligent reply, I would give: how can you make an intelligent political decision if you not received free and open advice from an Australian intellectual historian.

This is truly the historical understanding of Thucydides, Marx, and Nietzsche, and many more of speakers of truthfulness and holistic meaning.

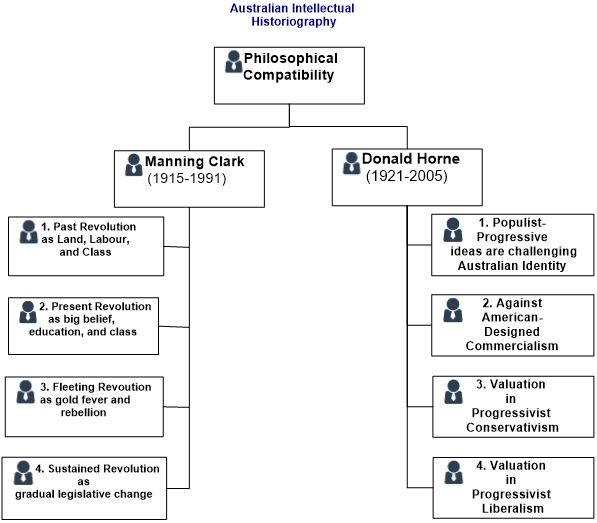

Featured Image: Designed and copyright by Dr Neville Buch ABN: 86703686642

by Neville Buch | Jul 24, 2015 | Uncategorized

Working with local history organisations has got me thinking about the crossover between group psychology and epistemology. If we are terribly honest with ourselves, historians – amateurs and professional alike, as with most human beings, we are petty empire-builders. It’s not that we are tyrants, or most of us are not, and we still value and act upon other things – particularly, for historians, on scholarship. But, attitudinally, most of us have a patch of scholarship, or some other work or play, that is our own, and we find ourselves threatened by what others are doing in the neighbourhood. Sometimes we lash out at or snub things and persons we don’t understand.

There are a number of psychological theories which might help explain why we, or maybe just I, don’t seek further understanding. It seems to me, observing many persons, that often the short-sightedness of any particular person is obvious to other persons around them. However, other people do not always find that same understanding – what the particular person has missed has escaped their attention. I wonder what I have missed. Among the psychological theories are cognitive dissonance and self-perception. A number of other psychological theories may also shed light on behaviour in this context, such as cost-benefit , and free-choice . What strikes me in the debates are several observations:

- People actively avoid situations and information likely to increase cognitive dissonance – the discomfort from holding contradictory beliefs, ideas, or values, or dealing with new information that conflicts with existing beliefs, ideas, or .

- People do not think much about their attitudes, let alone whether they are in conflict. They can come to conclusions as observers without much (or no) emotional or intellectual (cognitive)

Nevertheless, in spite of an over-emphasis in rational process or agency, there are basic elements in reasoning and choice which ought not to be ignored. Ideas on action and motivation may also provide some illumination. We continue to make ethical judgements. We can identify a person’s motivation as malice, intellectual laziness, or just plain ignorance. These are what Bernard Williams called thick concepts – the way we, at the same time, combine our valuation and facts of the matter in . We see it in others because we think and feel in the same way. It is an inescapable part of our socialization. It is also a fact about how the brain is “wired”. The big mistake of the ancients, and which we continue in modernity, is to emphasize the difference between emotion and reason.

Neuro-psychology is also a very important tool, but in describing brain function, explanation never escapes language, and language, as with any perception or psychological state, is from its only position of being the conscious being, and hence, from inside the norms of psychology. We don’t observe the brain from the outside of a brain. Although we believe that we have a better, scientific, understanding of our attitudinal states, we cannot be reductive in the way we live our lives. Ordinary and common social psychology and ethical judgements still come into play. What is needed is a fuller or more substantial consideration of our emotive-judgements, including the cognitive state in seeking objectivity.

So far the view here has been to a wider consideration of our attitudes. Something else is required. Unless we are a global skeptic, there is a special attitude which happens when we say we know something. It has become fashionable from post-modernist reasoning to abandon all endeavours in epistemology – to be able to say that what we claim as knowledge has a special status among beliefs. However, from the fact that radical post-modernity is forced, in the end, to reason itself into existence, we can see that there is a plain and vicious contradiction through which it just cannot leap out through faith. After being burnt once by hoodwinking liars and fools, people learn to evaluate reason. Our brain is wired to learn the difference between good and bad reasoning, and socially this becomes the process of learning critical thinking strategies – knowing the difference between logical arguments (good reasoning) and fallacies (bad reasoning). What the radical post-modernists have not noticed is that in understanding the role of passion, or the non-rational elements in cognition, reasoning is inescapable. The true global skeptic is forced to admit that he has no understanding.

To understand, the conscious being has to make judgements, and inevitably a series of judgements that flow from one conclusion to another. In living our lives, most of the time we do not reflect on that cognitive process. Reflection, though, enables us to identify the knowledge we believe we have. That we actually have knowledge is the project of epistemology. What this comes to, for historians, is an on-going applied epistemology in our work. It is using the skeptic’s doubt as a tool to refine our conclusions or overthrow them if they come up short. It is true that what I have explained here is far too simple if we were to push deeply into the epistemic field. Nevertheless, the epistemic boot-strapped grounding is still sufficient for what we do.

Many thanks to psychologist, Dr Kelly Dixon, and philosopher, Daniel Halverson, for reviewing this piece. Any omissions or errors are solely the responsibility of the author.