by Neville Buch | Dec 10, 2023 | 2023 Sydney-Auckland Tour, Article, Concepts in Educationalist Thought Series, The History Of Ruth

I am alone, not like this blank page to which I start to write. We are thrown into a world (Heidegger).

I woke up slowly this morning. I slept in. Each morning since 17 December 2016, I awake with a sense of disorientation, and in loss and grief. I am alone.

Isolation is different from person to person, and what is common is the experience is only to a smaller group of persons. I am a widower who lost the love of his life at her young age of 55 years. The context immediately places the loss and grief in a certain way. My wife was “sick” with a brain cancer and I was her carer for seven years. It has been seven years since Ruth died. While Ruth lived with the ‘death sentence’, she was determined to live life as best she could on her own terms. Her work career had just started after many years of study and parttime work, and then it was turned around. She took on a retired life in those seven years, that meant that I did not, or could not, engage as much as, in retrospect I wish I had. Worse, being close to her elderly mother it seemed to me that she became an elderly companion to her mother, well-aged beyond her actual years. It seemed I suddenly became married to a much older woman who I was caring for. It created something of a barrier for myself and my two daughters who were frustrated that their mother had prematurely loss her vigour. We had just hit on a solution to which Ruth agreed – that she would return to her social work studies – when the tumour returned, and her hope for an M.A. in social work was abandoned. Then the laborious and dark year of 2016, of initial vain hope, heartbreak, and isolation. Ruth died alone. Ruth did not die alone. It is a paradox. No one could really be there for Ruth as she was in the dying stages of six months. She was alone, slipping away from us. Nevertheless, we – I, family, friends – were in her presence to the end. I felt the distancing from the love of my heart. The love remained, but it became distant, as Ruth slipped into long periods of sleep, and there was less engagement to express love: too few hugs, too few words. The barrier was also self-preservation in the shock of losing not only a loved one, but my life, my life with Ruth. Ruth was alone. I was alone.

Writing these words on the remaining blank page, tears are running down my face after seven years.

Being alone, however, in the last seven years has another dimension.

I have just completed four conferences in two weeks, as I write these words on a Sunday morning and afternoon from Room 603 at the Marriot in Auckland. It is a sign of an achievement in my new life, and yet I feel very much alone, a different kind of aloneness. In my life with Ruth, we had compromised much in our work careers, mutually. Both of us lost those opportunities of advancing in our career. Both of us had hopes for advancement, but I was particularly ambitious to be the teacher and researcher at the head podium of the conference. But to achieve such ambitious status, I would have to have had the paid position in the university, but much more, I would have had to put in the required hours away from the family. This was not possible in life with Ruth, and it was part of our mutual compromise.

Now in the absence of Ruth, the opportunities have come too late. For the whole of my life, with or without Ruth, it was always too late: too late to make my own mark in the cognitive revolution of the 1960s and 1970s, being too young. Too late as an undergraduate student, moving on into my late 20s. Too late as a doctoral student in my early 30s, which meant too late in my initial career as a higher education researcher in my late 30s. Very few excelling scholars can get ahead of the crowd and stake the direction of the mass culture. Working in a university office, you are in the midst of the madness with temporary and insignificant tasks. It was only in the years after I left the Office of Vice-Chancellor, University of Melbourne, that it made any sense what was happening. It is the concept of historical distancing. Hegel’s ancient owl. Now, I can write the exceptionally important papers for the intellectual histories of higher learning, but, tragically, my colleagues have moved onto other important and critical matters; so, who cares what a 62-year-old has to say, “isn’t he retired.” I am alone.

Furthermore, what I have to say is incredibly discomforting to my university colleagues who remain in the madness. I am saying, for the communities I work for, is that academics across the fields, are only “shifting the deckchairs” of higher learning, and higher learning still remains as aloof to the lebenphilosophie of public space communities. There are too few scholars, who are actually inside the public space communities, translating the vast literature of higher learning, and we are the ones with the crushed university ambitions. And we are also the ones without payment for our work since voluntary work is so undervalued in our society. Academics talk about doing voluntary work for the scholarly societies but they forget that they do so from a wage that is paid by the university. I am alone.

Ambition is thawed away, not merely in the closed-off opportunity. One is self-aware of the shortfall of living one’s life. For me, it was always languages. It was something in my childhood disposition, that growing up I could never distinguish well, audiologically, in pronunciation and tone. Tone also meant that I could express anger without understanding the tone heard as aggression. If I felt the aggression in myself, I had translate it as frustration at the lack of attention I felt I was receiving. Life had meant I knew humility, but the lack of attention was interpreted in my historian’s frame: I was continually misunderstood due to wilful historical forgetfulness. Academics caught up in rabbit holes of specialisation just did not want to know, and why should they care? I was alone.

I must admit to the marginality of attending and participating in the four conferences, and that I was not alone. It is a similar paradox of the life with Ruth, mentioned above. Academics feel that their position is at the margins. Everyone in public space communities feel at the margins. It is a strange life-experience of being alone, and very much not alone. So, to get academic attention, what does the literature says on being alone?

Most the literature relates dispassionate and clinical studies, as expected, but there were nine works directly related to my argument on being alone (Hughes and Gove 1981; Ranta, Rita, Lindstrom 1993; Stack 1998; Coleman 2009; Gaymu, Springer, and Stringer 2012; Demey, Berrington, Evandrou, and Falkingham 2014; Holt-Lunstad, Smith, Baker, Harris, and Stephenson 2015; Frank, Froese, Hof, Scheffold, Schreyer, Zeller, and Rödder, 2017; Wilkinson, Tomlinson, and Gardiner 2017).

As to the dispassionate and clinical studies, the literature mostly focuses on the conditions of older persons in Asian cultures and philosophies (Raymo 2015; Kim 2015; Min-Ah Lee 2016), with two European or western paralleled concern (Kemp and Acheson 1989; de Jong, Dykstra, Schenk 2012). Another area of clinical concern was young persons living alone in one-person households (Cheung and Yeung 2015, 2021);

- Raymo (2015) uses Japanese census data to evaluate how much of the growth in one-person households at ages 20–39 between 1985 and 2010 is explained by change in marital behaviour and how much is explained by other factors. The analyses indicate that marital behaviour had correlated with certain increase in one-person households for men and three-fourths of the increase for women. That is interesting but that does not go anywhere in understanding the film, Lost in Translation. Surprise, surprise, the second set of analyses indicated that those living alone are significantly less happy than those living with others.

- Kim (2015) has a more honest appraisal from the data, concluding it is not clear whether public transfers for the elderly will increase or decrease their independent living. Furthermore, as is supported in much intergenerational studies of the last 60 years, multigenerational co-residence is prevalent and norms and preferences for that form of living arrangement remain strong. I do love my daughters living at home when they do;

- Min-Ah Lee (2016) used data from the four waves of the Korean Longitudinal Study of Ageing (KLoSA) over a period of six years, discrete time event history analyses were conducted to analyse the determinants of the transition to living alone for older Koreans. What was found was that home ownership and higher household income at a previous wave were negatively associated with the transition to living alone in general, whereas prior depressive symptoms were positively associated with the transition to living alone for older Koreans. It is certainly counter-intuitive. To say, physical health conditions did not have significant effects on the transition to living alone is aggressively opposite of the lebenphilosophie, as the global population finds it. Although Min-Ah Lee does conclude that the transition to living alone in disadvantaged older adults may amplify the harmful effects of living alone on their well-being in the long run, his approach to the data is problematic. Statistics is always subject to false reading from what the expectations of the participants have in what should be reported;

- In 1989 Kemp and Acheson did better work in tying the experience of being alone to the care of community. They sampled 2,000 elderly people from 20 general practitioner practices in the East Anglia area. Those living alone exhibit a higher level of independence than those living with others, but nearly a quarter of those aged 75 and over living alone did rely on someone else entirely for specific tasks;

- de Jong et al (2012) used data from the Generations and Gender Surveys of three countries in Eastern Europe and two countries in Western Europe. Latent Class Analyses was applied to develop intergenerational support types for (a) co-residing respondents in Eastern Europe, (b) respondents in independent households in Eastern Europe, and (c) respondents in independent households in Western Europe, respectively. On this basis, a six-way typology was produced. It is fascinating reading, but, again, the lebenphilosophie is simply not there;

- In Cheung and Yeung’s (2015, 2021) major paper, they drew data (from previous studies to the meta-data) from a subsample of young adults (aged between 20 and 35) from China 1% Population Sample Survey 2005 (ni = 582,139; nj = 345). They concluded that young adults living in one-person households (OPHs) had increased remarkably worldwide. This analysis is informative to both living alone and having to migrate to live alone. A second paper was published, but it appears almost the same as the earlier study.

There is an academic game-playing which distorts the intelligence in the academic research and findings, and particularly, missed lebenphilosophie.

As to the actually academic articles writing on the being alone:

- In 1981 Hughes and Gove immediately went to the much better research, and providing an examination of the effects of living alone on mental health, mental well-being, and maladaptive behaviours. Their work reflects the general ethos of the 1980s, in that there was much more concern among academics for compatibilist philosophy and horizon worldviews. The work in academy, in later decades, trended the statistical analysis without the quality consideration of the philosophic concepts in the works. Hughes and Gove showed there is no evidence that persons who live alone are selected into supported living arrangement because of preexisting psychological problems, noxious personality characteristics, or incompetent socioeconomic behaviour, and that, contrary to structural functionalism or symbolic interactionism, unmarried persons who live alone are in no worse, and on some indicators are in better, mental health than unmarried persons who live with others. The big gap in their work is the absence of references to widows and widowers. Most academics cannot deal with loss and grief until it becomes their own lebenphilosophie;

- In 1993 Ranta et al produced a very bland paper, which reported to speak to “Competition Versus Cooperation”, Admittedly it was an anthropological paper about food foraging alone and in groups. They argued that the option of foraging alone may easily be a better strategy than that of a low-ranking individual foraging in a group. However, as a generic argument, it is bullshit. As interdisciplinary scholars are aware, the competitive and Darwinian social models does not work for the benefit of the individual nor the group. The argument of Ranta et al is so obviously agenda-ed, as all academic works are. There is no evidence that the lebenphilosophie of a low-ranking individual is better without the deep group interaction and worldview;

- In 1998 Stack pointed out that previous research on loneliness had often neglected the role of marriage and family ties, comparative analysis, and cohabitation. Using the data from 17 nations in the World Values Survey, they concluded (1) marriage is associated with substantially less loneliness, but parenthood is not, (2) being married was considerably more predictive of loneliness than cohabitation, indicating that companionship alone does not account for the protective nature of marriage, (3) both marriage and parental status were associated with lower levels of loneliness among men than women, (4) marriage is associated with decreased loneliness independent of two intervening processes: marriage’s association with both health and financial satisfaction, (5) the strength of the marriage-loneliness relationship is constant across 16 of the 17 nations. Again, there is not the consideration of the end of marriage through experience of ‘pre-mature’ death;

- In the new century Coleman (2009) went to the characteristic urban experience of solitude and its challenges to traditional anthropological theories of urban life. It challenged theoretical perspectives with ethnographic cases of gay identities and ‘being alone together,’ drawn from fieldwork in New Delhi, India. Personally, in the different context of heterosexuality, I found Colman’s heuristic concept of ‘social solitude’, in contrast to ‘solidarity’, and his examination of the political and philosophical consequences of focusing on solitude as an urban way of life and an expression of sexuality, an epistemic fit. Coleman drew his informative model from a reading of Deleuze;

- Gaymu et al (2012), finally, lands on the lebenphilosophie directly. They looked at the influence of living conditions on the life satisfaction of men and women over 60 years of age in ten European countries using data from the European survey SHARE 2004 (wave 1). The features that they examine are the same of my lebenphilosophie argument: income levels, homeownership, and the relationship between family roles and economic status;

- Demey et al (2014) examined studies which found that the duration since a union dissolution and the number of union dissolutions are associated with psychological well-being. Again, the lebenphilosophie of widows and widowers are not relevant – not a matter of ‘union dissolution’ in the full semantics of the experience;

- Holt-Lunstad et al (2015) comes closer with an examination of actual and perceived social isolation in that both are associated with increased risk for early mortality. They conducted a literature search of studies (January 1980 to February 2014) using MEDLINE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, Social Work Abstracts, and Google Scholar. Again, the interdisciplinary scholarship shows that there is something is wrong, when concluding no differences between measures of objective and subjective social isolation. Their approach was admittedly, marginally, to the compatibilism side, and they did say, “the influence of both objective and subjective social isolation on risk for mortality is comparable with well-established risk factors for mortality”, but that overlooks many object-subject lessons in the interdisciplinary knowledge;

- Frank et al (2017) go directly to my main point here: “The ability to conduct interdisciplinary research is crucial to address complex real-world problems that require the collaboration of different scientific fields, with global warming being a case in point.” Their classroom experiment reminds me of David Kayrouz’s presentation at the PESA conference on knowing and knowledge (images of Kayrouz’s models in the photo album);

- Wilkinson et al (2017), finally, goes to my sorrowful-happy reflections of my life with Ruth, with their examination of the dominant understanding of work–life balance or conflict as primarily a ‘work–family’ issue by exploring the experiences of managers and professionals who live alone and do not have children – a group of employees traditionally overlooked in work–life policy and research but, significantly, a group on the rise within the working age population. Of course, Ruth and I had two wonderful children, but Wilkinson et al’s analysis does not go to lebenphilosophie of widows and widowers, with or without children.

The always continuing conclusions

I have spent this Sunday writing this “academic article”, without family close-by, and without a loving partner, has provided the insight to what being alone is about. As an interdisciplinary scholar, outside the university, and for the public square community, I am alone. So much for academic collegialism! Still, I am supported in kindness by individual academics and former academics. And I thank them dearly, for when I do not feel alone.

REFERENCES

Cheung, A. K.-L., & Yeung, W.-J. J. (2021). Socioeconomic development and young adults’ propensity of living in one-person households: Compositional and contextual effects. Demographic Research, 44, 277–306. https://www.jstor.org/stable/27032913

Coleman, L. (2009). Being Alone Together: From Solidarity to Solitude in Urban Anthropology. Anthropological Quarterly, 82(3), 755–777. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20638659

de Jong Gierveld, J., Dykstra, P. A., & Schenk, N. (2012). Living arrangements, intergenerational support types and older adult loneliness in Eastern and Western Europe. Demographic Research, 27, 167–200. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26349921

Demey, D., Berrington, A., Evandrou, M., & Falkingham, J. (2014). Living alone and psychological well-being in mid-life: does partnership history matter? Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health (1979-), 68(5), 403–410. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43281754

Frank, A. M., Froese, R., Hof, B. C., Scheffold, M. I. E., Schreyer, F., Zeller, M., & Rödder, S. (2017). Riding alone on the elevator: A class experiment in interdisciplinary education. Learning and Teaching: The International Journal of Higher Education in the Social Sciences, 10(3), 1–19. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48561574

Gaymu, J., Springer, S., & Stringer, L. (2012). How does Living Alone or with a Partner Influence Life Satisfaction among Older Men and Women in Europe? Population (English Edition, 2002-), 67(1), 43–69. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23358620

Holt-Lunstad, J., Smith, T. B., Baker, M., Harris, T., & Stephenson, D. (2015). Loneliness and Social Isolation as Risk Factors for Mortality: A Meta-Analytic Review. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 10(2), 227–237. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44290063

Hughes, M., & Gove, W. R. (1981). Living Alone, Social Integration, and Mental Health. American Journal of Sociology, 87(1), 48–74. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2778539

Kemp, Frances M., and Roy M. Acheson. “Care in the Community – Elderly People Living Alone at Home.” Community Medicine 11, no. 1 (1989): 21–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45156782.

Kim, E. H.-W. (2015). Public transfers and living alone among the elderly: A case study of Korea’s new income support program. Demographic Research, 32, 1383–1408. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26350156

Min-Ah Lee. (2016). Effects of Economic and Health Conditions on the Transition to Living Alone: A Longitudinal Study on Older Koreans. Development and Society, 45(3), 591–617. http://www.jstor.org/stable/deveandsoci.45.3.591

Ranta, E., Rita, H., & Lindstrom, K. (1993). Competition Versus Cooperation: Success of Individuals Foraging Alone and in Groups. The American Naturalist, 142(1), 42–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/2462633

Raymo, J. M. (2015). Living alone in Japan: Relationships with happiness and health. Demographic Research, 32, 1267–1298. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26350152

Stack, S. (1998). Marriage, Family and Loneliness: A Cross-National Study. Sociological Perspectives, 41(2), 415–432. https://doi.org/10.2307/1389484

Wilkinson, K., Tomlinson, J., & Gardiner, J. (2017). Exploring the work–life challenges and dilemmas faced by managers and professionals who live alone. Work, Employment & Society, 31(4), 640–656. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26500128

Yeung, W.-J. J., & Cheung, A. K.-L. (2015). Living alone: One-person households in Asia. Demographic Research, 32, 1099–1112. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26350146

by Neville Buch | Apr 26, 2024 | American-Australian Relational History, Concepts in Public History for Marketplace Dialogue, Concepts in UQ Philosophy and History, Important Public Statement

From ALEX BOLLINGER, “George Santos Boils In Rage After He Was Tricked Into Celebrating Pedophilia,” APRIL 25 2024, in CityWatch.

“LGBTQ – Disgraced former Congressman George Santos (R-NY) is willing to say anything to make a buck. He even made a video celebrating NAMBLA, the National Man/Boy Love Association, an organization that promoted pedophilia in the U.S.

…

When he was called out on social media for supporting the harmful group, he was outraged… at the woman who pointed it out.

…

Santos replied to Carducci, saying that he thought he was making a video for a person named “Nambla.” But instead of just admitting his mistake, he lashed out at Carducci with misogynist invective.”

The news story opens up what can be a philosophical definition of “Stupidity”. A politician dismissing “blame” via the dismissal he-she-it-they was ignorant. This does not work as an apologetic tactic. The Oxford definition:

Definitions from Oxford Languages · Learn more

stupidity

/stjuːˈpɪdɪti,stjʊˈpɪdɪti/

noun

behaviour that shows a lack of good sense or judgement.

“I can’t believe my own stupidity”

Similar:

lack of intelligence

unintelligence

foolishness

denseness

brainlessness

ignorance

mindlessness

dull-wittedness

dull-headedness

dullness

slow-wittedness

doltishness

slowness

vacancy

gullibility

naivety

thickness

dimness

dumbness

dopiness

doziness

craziness

folly

silliness

idiocy

senselessness

irresponsibility

injudiciousness

ineptitude

inaneness

inanity

irrationality

absurdity

ludicrousness

ridiculousness

fatuousness

fatuity

asininity

pointlessness

meaninglessness

futility

fruitlessness

madness

insanity

lunacy

daftness

Opposite:

genius

sagacity

the quality of being stupid or unintelligent.

“a comedy of infantile stupidity”

Wikipedia says, “Stupidity is a lack of intelligence, understanding, reason, or wit, an inability to learn. It may be innate, assumed or reactive.”

When I use “Stupidity” in my work, I am particularly using the semantics of ‘a lack of intelligence’, the ‘inability to learn’, and the model of reactionary thinking (‘reactive’). This is why pleading ignorance does not save anyone from a charge of stupidity. It is not the synonym “ignorance” which is on display, but

- a lack of intelligence’;

- the ‘an inability to learn’; and

- the model of reactionary thinking (‘reactive’).

REFERENCE

Alvesson, M., & Einola, K. (2018). Excessive work regimes and functional stupidity. German Journal of Human Resource Management / Zeitschrift Für Personalforschung, 32(3/4), 283–296. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26905591

Bennington, G. (2011). A Moment of Madness: Derrida’s Kierkegaard. Oxford Literary Review, 33(1), 103–127. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44030838

Brunsson, K. (2020). Effective or Stupid? – A Note on the Organizational Economy. Management Revue, 31(1), 92–109. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26996603

Carrier, D. (1998). The Pleasures of Stupidity: Gary Larson as a Baudelairean Caricaturist. Nineteenth-Century French Studies, 27(1/2), 62–70. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23537558

Dillet, B. (2013). What Is Called Thinking?: When Deleuze Walks along Heideggerian Paths. Deleuze Studies, 7(2), 250–274. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45331542

Feyaerts, K., & Brône, G. (2005). Expressivity and Metonymic Inferencing: Stylistic Variation in Nonliterary Language Use. Style, 39(1), 12–36. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/style.39.1.12

Hall, R. B. (2009). The New Alliance Between the Mob and Capital (and the State). St Antony’s International Review, 5(1), 11–26. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26227136

Heldke, L. (2006). Farming Made Her Stupid. Hypatia, 21(3), 151–165. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3810956

Hutchings, K. (2018). War and moral stupidity. Review of International Studies, 44(1), 83–100. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26619466

Massey, H. (2011). When Are We When We Think? Arendt’s Temporal Interpretation of Thinking and Thoughtlessness. Philosophical Topics, 39(2), 71–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43154605

Penteado, B. (2015). The Epistemology of the Parrot. Nineteenth-Century French Studies, 43(3/4), 144–157. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44122722

Polachan, W. (2014). Buddhism and Thai Comic Performance. Asian Theatre Journal, 31(2), 439–456. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43187435

Robertson, D. G. (2015). Conspiracy Theories and the Study of Alternative and Emergent Religions. Nova Religio: The Journal of Alternative and Emergent Religions, 19(2), 5–16. https://doi.org/10.1525/nr.2015.19.2.5

Saxton, A. (2009). The God Debates and the Materialist Interpretation of History. Science & Society, 73(4), 474–497. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40404591

Segall, S. (2010). Is Health (Really) Special? Health Policy between Rawlsian and Luck Egalitarian Justice. Journal of Applied Philosophy, 27(4), 344–358. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24356088

Zins, D. L. (1986). Rescuing Science from Technocracy: “Cat’s Cradle” and the Play of Apocalypse (Sauver la science de la technocracie: “Le berceau du chat” et le Jeu de l’Apocalypse). Science Fiction Studies, 13(2), 170–181. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4239744

Featured Image:Mind-Reality-dreamstime_xs_45497563.jpg

Perspectives Of Mind

by Neville Buch | Sep 23, 2024 | American Revivalist Tradition (ART), Concepts in Religious Thought Series

Getting knocked back for a publication is not a concern, in and of itself, but the issue is how today’s academics are not yet understanding the emerging scholarship of cognition histories and cognition sociology.

Below is such a rejection letter. Here is the edited submission of the draft where there was scope for a process of learning:

Fundamental Theology, Second Edition- NDB Accepts VL edits

I let you be the judge of my review draft article’s content and messaging: whether it is appropriate, and where it meets the standards of scholarship. Further below is an explanation.

Dear Neville,

The JASR Book Reviews editor passed the attached review on to us, the Co-Editors. She is considering declining the review but wanted a second opinion. Having read the review, we concur that the review is not publishable. While we understand the Book Reviews editor agreed to a review of this book, we think the book itself is not of sufficient interest to JASR readers to warrant a review, furthermore, the quality is not of the standard we expect.

The process to get to this point has been frustrating for all concerned. There are two options moving forward: either, the reviews you submit should require minimal editorial oversight and work to be publishable, and the tone of your communication with the Book Reviews Editor should remain professional; or we will no longer accept your reviews for publication in JASR.

Warm Regards,

Rosie

Rosemary Hancock

Academic Lead, Graduate Research

Senior Lecturer and Convener, Religion, Culture and Society

The University of Notre Dame Australia

Co-Host, Uncommon Sense

Co-Editor, Journal

I acknowledge the Traditional Owners – the Gadigal people of the Eora Nation – upon whose ancestral land I live and work, and pay my respects to Elders past and present.

Disclaimer

IMPORTANT: This e-mail and any attachments may be confidential. If you are not the intended recipient you should not disclose, copy, disseminate or otherwise use the information contained in it. If you have received this e-mail in error, please notify us immediately by return e-mail and delete or destroy the document. Confidential and legal privilege are not waived or lost by reason of mistaken delivery to you. The University of Notre Dame Australia is not responsible for any changes made to a document other than those made by the University. Before opening or using attachments please check them for viruses and defects. Our liability is limited to re-supplying any affected attachments.

To demonstrate the knowledge, it has, today, been confirmed in the Australian and New Zealand History of Education Society (ANZHES) my abstract for the 2024 conference. It speak to the global cognition histories and cognition sociology where Australian academics are generally out-of-touch:

Resolving Educational Epistemology to Defeat the Culture-History War

The paper is an accumulation of thinking for the last three decades and represented in the recent work of David W. Kim and Duncan Wright (2024, edited). The main issue is “the problem of schooling.” (Illich 1971 and Collins 1998)

None of this is new knowledge, which has been understood for well-over a half century, particularly as philosophy of educational anthropology, sociology and historiography (e.g., Voget 1960). Even in the early 21st century, educators still think and talk in the modes of 19th century evolutionists (Voget 1960:943): “As anthropologists groped their way forward to a distinctive reality for their discipline, selecting culture as their proper focus and domain, some claimed to have settled the issue of human nature and culture, but more often the issue was dispersed in immediate engagements, such as historicism, culturalism, and functionalism.” What many educators are wilfully ignorant of is “the rise of social interactionism and new linkages with sociology.”

The History of Education goes as far back as Rudolf Steiner (1886, 1892). Buch argues that the Australian education system suffered for three reasons: 1. An uncritical understanding of Anglo-American Major Belief-Doubt Systems (Buch 2023) due to the gutting of intellectual history courses and research programs in Australian universities; 2. An uncritical understanding of how ideological systems pervasively work in the Australian education system, something well-understood from the North American context (Giroux 1981, Aronowitz and Giroux 1985); and 3. An inability (to date) for Australian curriculum writers and authorities to critically and comprehensively understand and apply the global history in the educational histories (e.g., Watt 1981, Kolig 1995, Popkewitz 1997, Paul and Marfo 2001, Roberts 2015). There are several explanations for the state of affairs in the Australian educational curriculum and authorities. Kaaronen (2018) points to the neglected need to “Reframing Tacit Human–Nature Relations.” Warnke (2015) points to confusions in “Philosophical Hermeneutics and the Politics of Memory.” A good example is the historical forgetfulness of today’s academics in “the problem of knowledge” discourses (as an example of the memory history, Fenstermacher and Sanger 1998).

The full paper will be the unpacking of the recent history of education, as stated above.

REFERENCES

Aronowitz, Stanley and Henry A. Giroux (1985). Education Under Siege: The Conservative, Liberal and Radical Debate Over Schooling, Routledge.

Blum, P. (2010). Michael Polanyi: The anthropology of intellectual history. Studies in East European Thought, 62(2), 197-216. Retrieved May 7, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/40927717

Buch, Neville (1998-2008). Speeches and PowerPoint Presentations for Vice-Chancellors at the University of Melbourne (Professors Davis, Lee Dow, Gilbert) September 1998 to April 2008, and for Vice-Chancellor at Griffith University (Professor Webb) July 1997 to August 2008.

Buch, Neville (2020). Economic Rationalism and University Course Pricing 1989-2020, for Australian Policy and History, published online, August 3, 2020

Buch, Neville (2023). Research Note: Anglo-American Major Belief-Doubt Systems, https://www.academia.edu/104984588/Research_Note_Anglo_American_Major_Belief_Doubt_Systems , 27 July 2023.

Collins, Randall (1998). The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change, Harvard Unversity Press.

Fenstermacher, G. D., & Sanger, M. (1998). What is the Significance of John Dewey’s Approach to the Problem of Knowledge? The Elementary School Journal, 98(5), 467–478. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1002325

Illich, Ivan (1971). Deschooling Society. London: Calder & Boyars.

Giroux, Henry (1981). Ideology, Culture and the Process of Schooling, Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Kaaronen, R. O. (2018). Reframing Tacit Human–Nature Relations: An Inquiry into Process Philosophy and the Philosophy of Michael Polanyi. Environmental Values, 27(2), 179–202. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26535164

Kim, David W. and Duncan Wright (2024, edited), Socio-Anthropological Approaches to Religion: Environmental Hope (Rowman & Littlefield)

Kolig, E. (1995). A Sense of History and the Reconstitution of Cosmology in Australian Aboriginal Society. The Case of Myth versus History. Anthropos, 90(1/3), 49-67. Retrieved May 6, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/40463104

Paul, J. L., & Marfo, K. (2001). Preparation of Educational Researchers in Philosophical Foundations of Inquiry. Review of Educational Research, 71(4), 525–547. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3516097

Payne, P. G. (2015). Critical Curriculum Theory and Slow Ecopedagogical Activism. Australian Journal of Environmental Education, 31(2), 165–193. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26422893

Popkewitz, T. S. (1997). A Changing Terrain of Knowledge and Power: A Social Epistemology of Educational Research. Educational Researcher, 26(9), 18–29. https://doi.org/10.2307/1176272

Roberts, P. (2015). Chapter Four: Paulo Freire and the Idea of Openness, Paulo Freire: The Global Legacy (2015), in special Counterpoints edition, 500, 79–91. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45178205

Steiner, Rudolf (1886). Theory of Knowledge Implicit in Goethe’s World-Conception, New York: Anthroposophic Press.

Steiner, Rudolf (1892; Translated by R. F. A. Hoernle, 1921). Truth and Knowledge, doctoral thesis: Wahrheit und Wissenschaft Vorspiel einer “Philosophie der Freiheit.”, New York: Anthroposophic Press.

Voget, F. (1960). Man and Culture: An Essay in Changing Anthropological Interpretation. American Anthropologist, 62(6), new series, 943-965. Retrieved May 8, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/667593

Warnke, G. (2015). Philosophical Hermeneutics and the Politics of Memory. Perspectives on Politics, 13(3), 739–748. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43867353

Watt, A. J. (1981). Giovanni Gentile: Mussolini’s Favourite Educational Philosopher. The Journal of Educational Thought (JET) / Revue de La Pensée Éducative, 15(2), 124–136. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23768500

by Neville Buch | May 14, 2024 | Concepts in Educationalist Thought Series

The first in a series of articles about how today’s traditional-age college students experience the world — and how it affects their education.

Theresa MacPhail is a pragmatist. In her 15 years of teaching, as the number of students who complete their reading assignments has steadily declined, she has adapted. She began assigning fewer readings, then fewer still. Less is more, she reasoned. She would focus on the readings that mattered most and were interesting to them.

For a while, that seemed to work. But then things started to take a turn for the worse. Most students still weren’t doing the reading. And when they were, more and more struggled to understand it. Some simply gave up. Their distraction levels went “through the roof,” MacPhail said. They had trouble following her instructions. And sometimes, students said her expectations — such as writing a final research paper with at least 25 sources — were unreasonable.

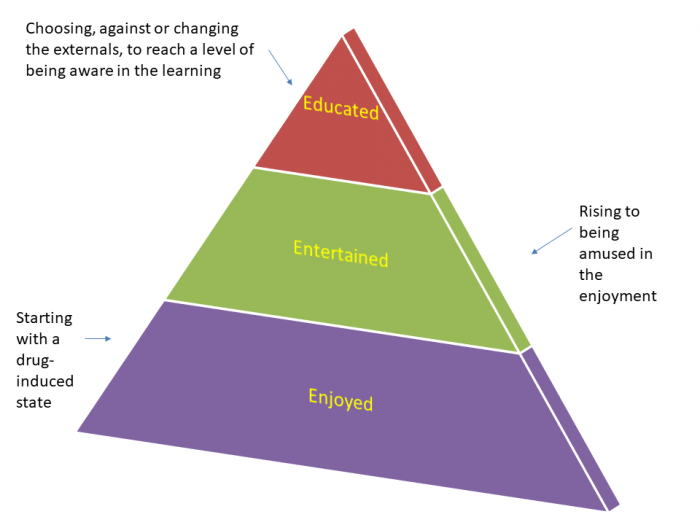

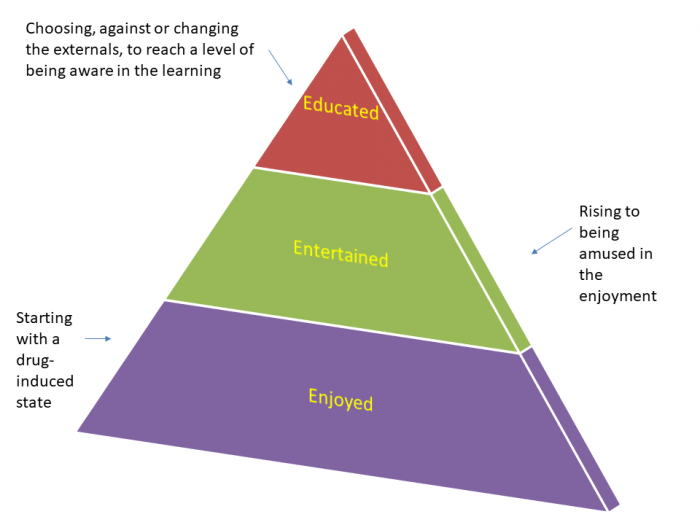

So, goes the reading of the opening paragraphs in Beth McMurtrie’s Is This The End of Reading? The Chronicle of Higher Education, MAY 9, 2024. The problem may have different elements but it does appear to come down to the issue of the entertainment mindset: a refusal to actually learn for a drug-like need to be entertain:

“If you make it easier, and go over what they should have read in class, students will participate. But then what are you doing, other than entertaining?”

Buch’s Pyramid Of Social Personal Development 700×525

It might be a waste of time to share this message with those who are actually reading what I am saying here. The persons who are caught up in the entertainment mindset, or drugged out their brain, are the persons who need assistance in changing their habits. There are many different guides to the practice of reading, some with substantive theory and other articles to be read with weak theoretical reading. In the References below are a selection of the reading, and the quality of the reading for each article I will leave up to the reader. As for Jennifer Rowsell and Anne Burke (2009), there are different types of learners when it comes to readers. Allow me to demonstrate one case of a misreading from one type of a poor learner, from Richard Cimino and Christopher Smith (2007).

Their primary and key message is:

“In conclusion, the secular humanist and atheist patterns of interaction and conflict discussed in this article suggest that these freethinkers’ hopes and visions of a secular America have been of little use in sustaining an identity within a highly religious (though pluralistic) society. In fact, the real and imagined culture wars and the forging of a subcultural identity may turn out to benefit the secular humanist movement far more than the much hoped for eclipse of faith and dawn of a humanist twenty-first century.” (2007: 424).

As the philosophical state of affairs within the United States, Richard Cimino and Christopher Smith (2007) have read correctly. As understanding global humanism, Cimino and Smith are very incorrect, dead wrong, and I can think of stronger language. The whole article is dominated by an American cultural way of thinking, I call the “American Revivalist Tradition” (ART). As the correct state of affairs Richard Cimino and Christopher Smith claim (2007: 407) for humanism:

- creating a niche for secular humanism among the unchurched and “secular seekers”;

- mimicking and adaping various aspects of evangelicalism, even as they target this movement as their main antagonist; and

- making use of minority discourse and identity politics.

Now, the reading mindset is entertainment for Richard Cimino and Christopher Smith because they get enjoyment out of the American cultural way of thinking. For global humanism, their ideals of Americanised humanism, makes humanists sick to the core. The American thinkers reject niches and “finding a place at the table.” Rather what they want is for “secularism to become a dominant force in the United States” and they are decrying the failure against compassionate and kind strategies (407).

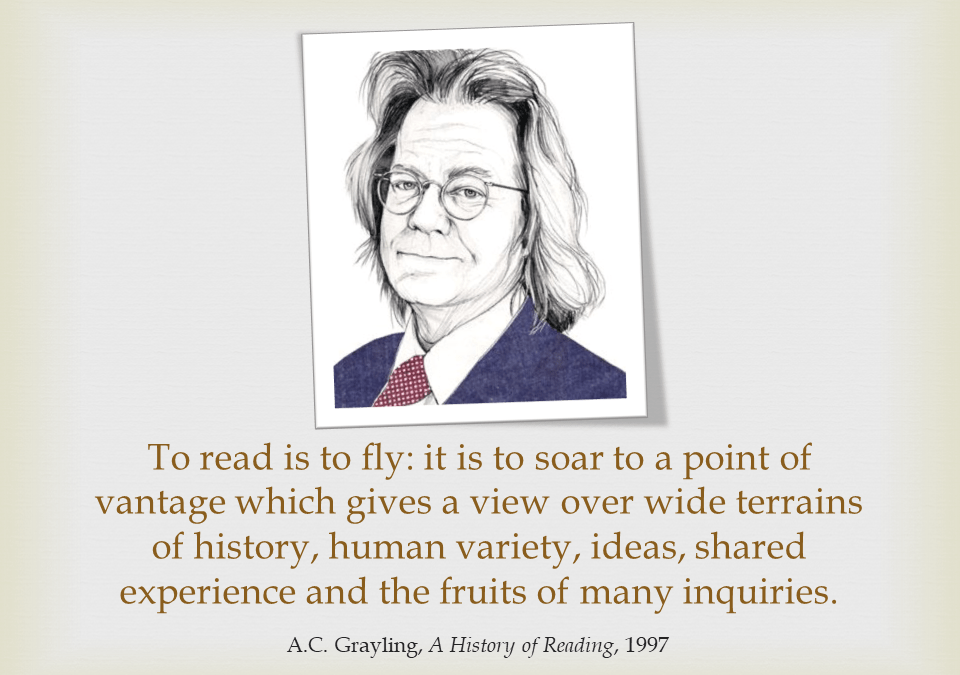

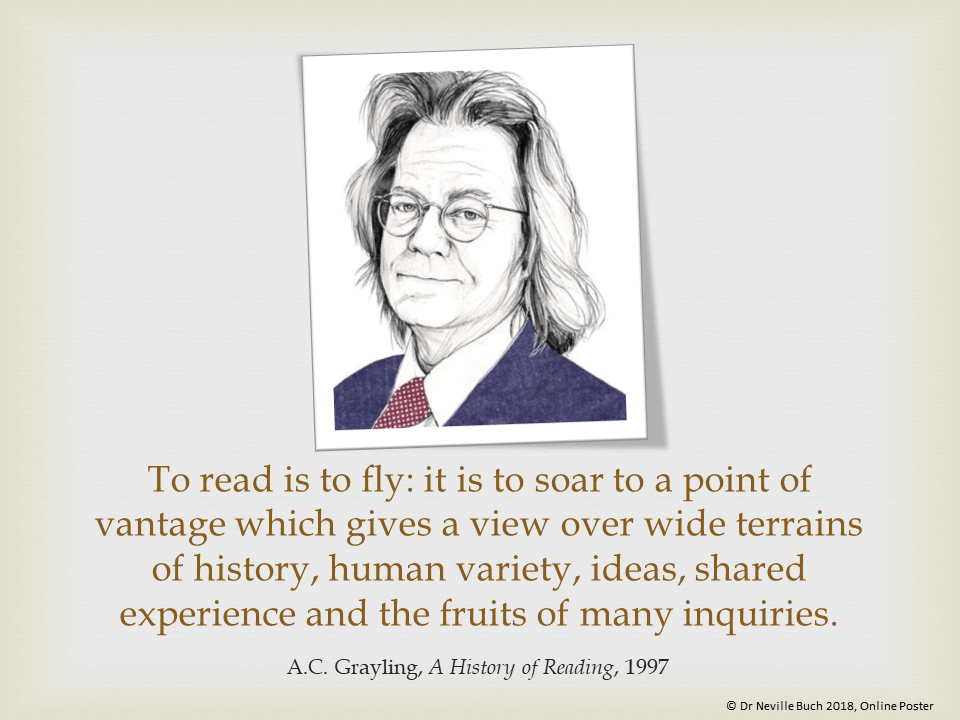

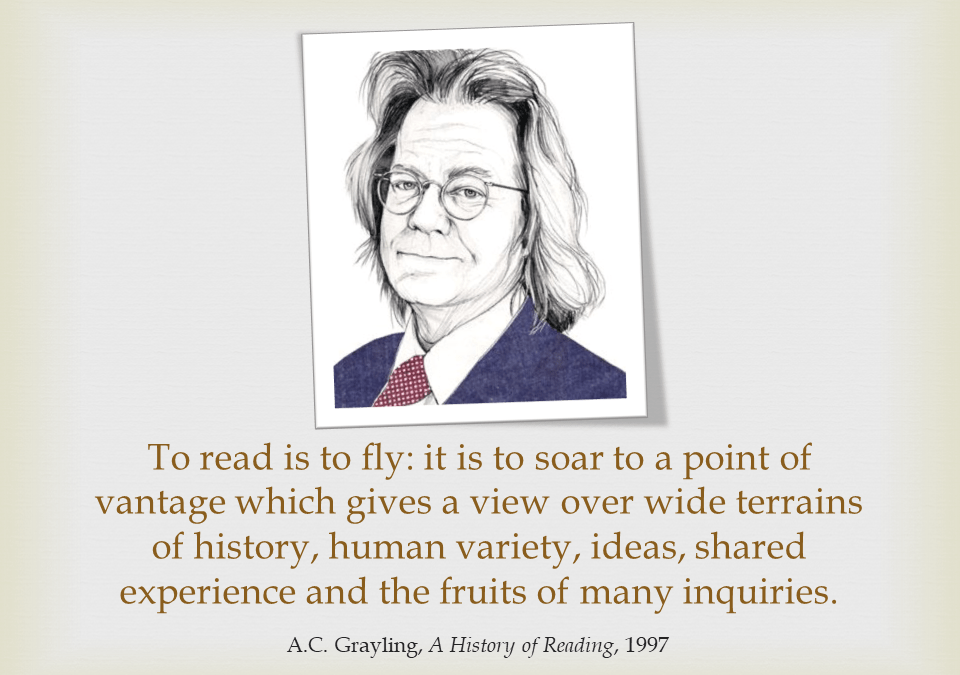

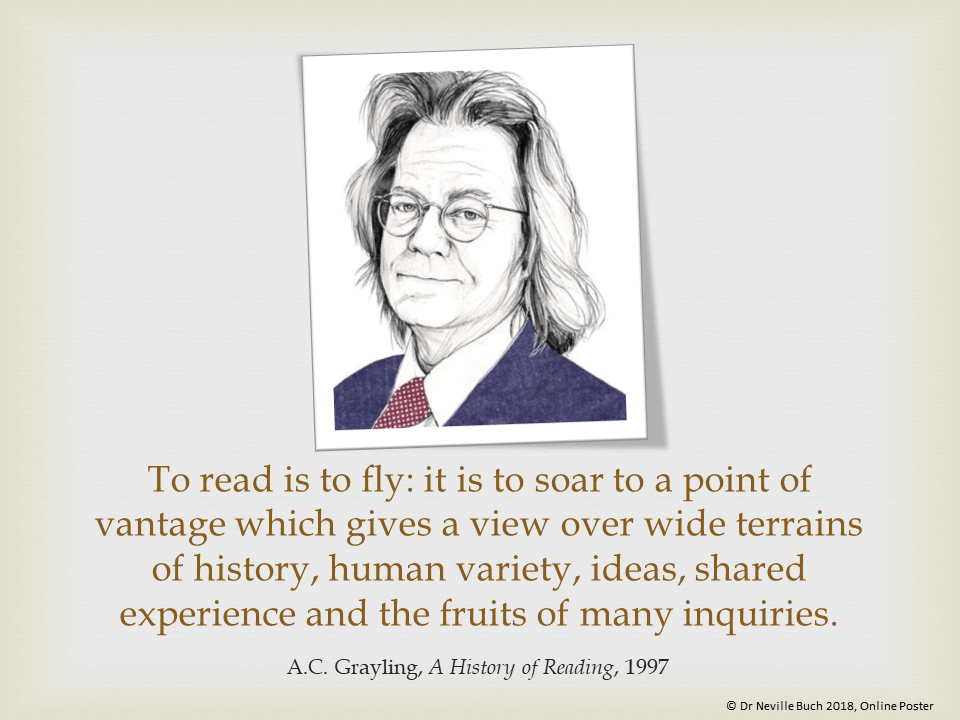

The cultural and reading attitude is what A.C. Grayling rejects in the quote, but, more than that, it teaches how to read:

” To read is to fly: it is to soar to a point of vantage which gives a view over wide terrains of history, human variety, ideas, shared experience and the fruits of many inquiries “

REFERENCE

Cimino, R., & Smith, C. (2007). Secular Humanism and Atheism beyond Progressive Secularism. Sociology of Religion, 68(4), 407–424. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20453183

DelConte, M. (2003). Why You Can’t Speak: Second-Person Narration, Voice, and a New Model for Understanding Narrative. Style, 37(2), 204–219. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5325/style.37.2.204

Hamington, M. (2015). Care Ethics and Engaging Intersectional Difference through the Body. Critical Philosophy of Race, 3(1), 79–100. https://doi.org/10.5325/critphilrace.3.1.0079

Jackson, I. (2004). Approaches to the History of Readers and Reading in Eighteenth-Century Britain. The Historical Journal, 47(4), 1041–1054. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4091667

Jolley, K. (2008). Video Games to Reading: Reaching out to Reluctant Readers. The English Journal, 97(4), 81–86. http://www.jstor.org/stable/30047252

Kort, W. A. (2013). Calvin’s Theory of Reading. Christianity and Literature, 62(2), 189–202. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44324128

Newell, G. E., Beach, R., Smith, J., VanDerHeide, J., Kuhn, D., & Andriessen, J. (2011). Teaching and Learning Argumentative Reading and Writing: A Review of Research. Reading Research Quarterly, 46(3), 273–304. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41228654

Robertson, J. E. (1968). Pupil Understanding of Connectives in Reading. Reading Research Quarterly, 3(3), 387–417. https://doi.org/10.2307/747011

Stivers, C. (1994). The Listening Bureaucrat: Responsiveness in Public Administration. Public Administration Review, 54(4), 364–369. https://doi.org/10.2307/977384

Sweeney, M. A., & McBride, M. (2015). Difficulty Paper (Dis)Connections: Understanding the Threads Students Weave between Their Reading and Writing. College Composition and Communication, 66(4), 591–614. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43491902

Rowsell, Jennifer, and Anne Burke. “Reading by Design: Two Case Studies of Digital Reading Practices.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 53, no. 2 (2009): 106–18. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40344356.

Vallecorsa, A. L., & deBettencourt, L. U. (1997). Using a Mapping Procedure to Teach Reading and Writing Skills to Middle Grade Students with Learning Disabilities. Education and Treatment of Children, 20(2), 173–188. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42899487

Wolf, M. (2018). The science and poetry in learning (and teaching) to read. The Phi Delta Kappan, 100(4), 13–17. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26552479

Wu, S., & Pope, A. (2019). Three-Level Understanding: Recovering Self-Awareness in the Art of Critical Thinking. Journal of Thought, 53(1 & 2), 21–37. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26727283

Featured Image:

Slide 026. Grayling On Reading

by Neville Buch | Apr 10, 2023 | Article, Blog, Concepts in Educationalist Thought Series, Concepts in Public History for Marketplace Dialogue, Concepts in Religious Thought Series, Road Trips, The Importance Of History In Our Own Lives?

Dr Neville Buch’s Philosophy and History Article: Downloadable PDF Version

2018-08-30 Neville at the 2018 PHA Conference, ASKING THE QUESTIONS AND PROVIDING THE FRAMEWORKS

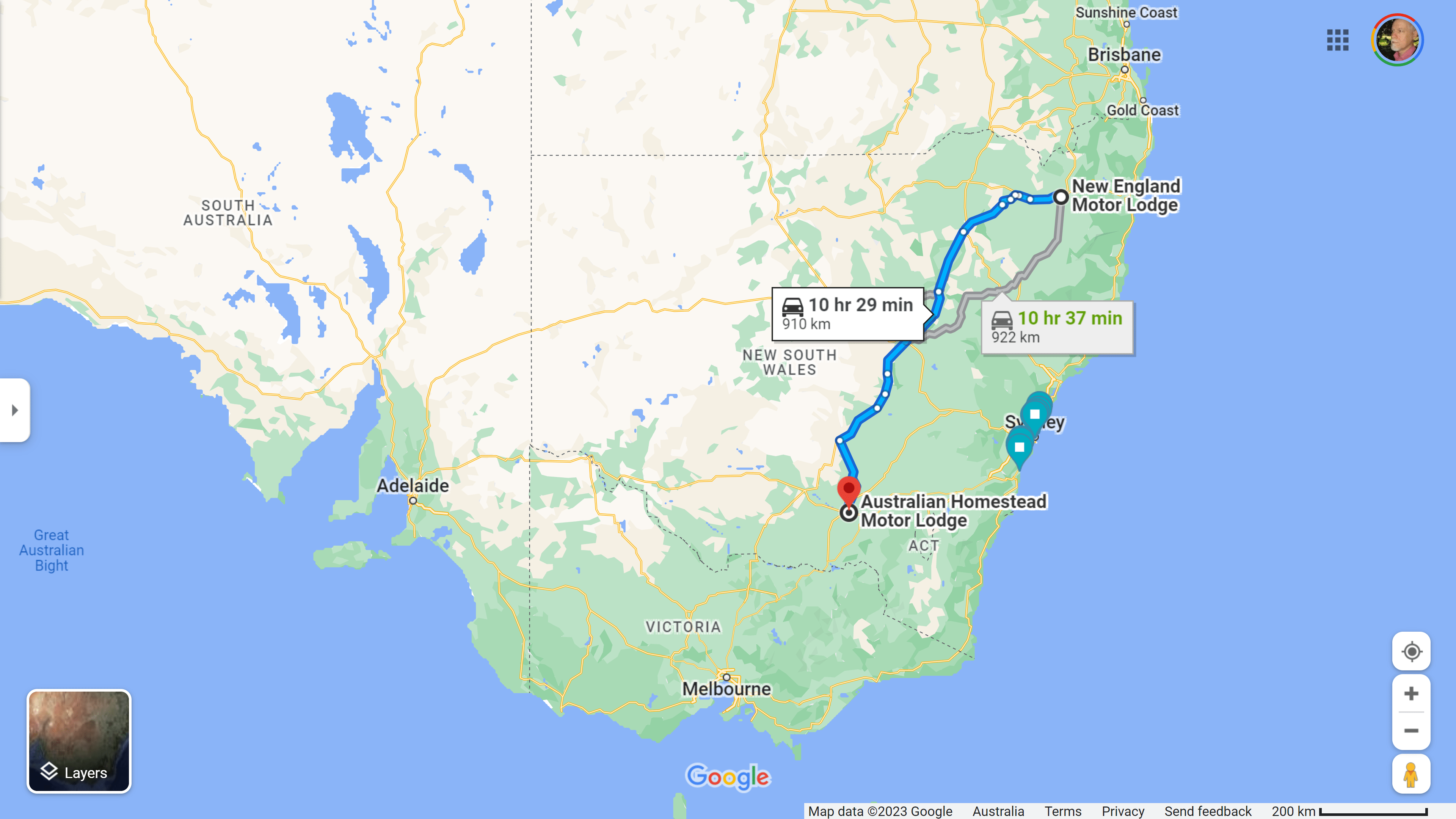

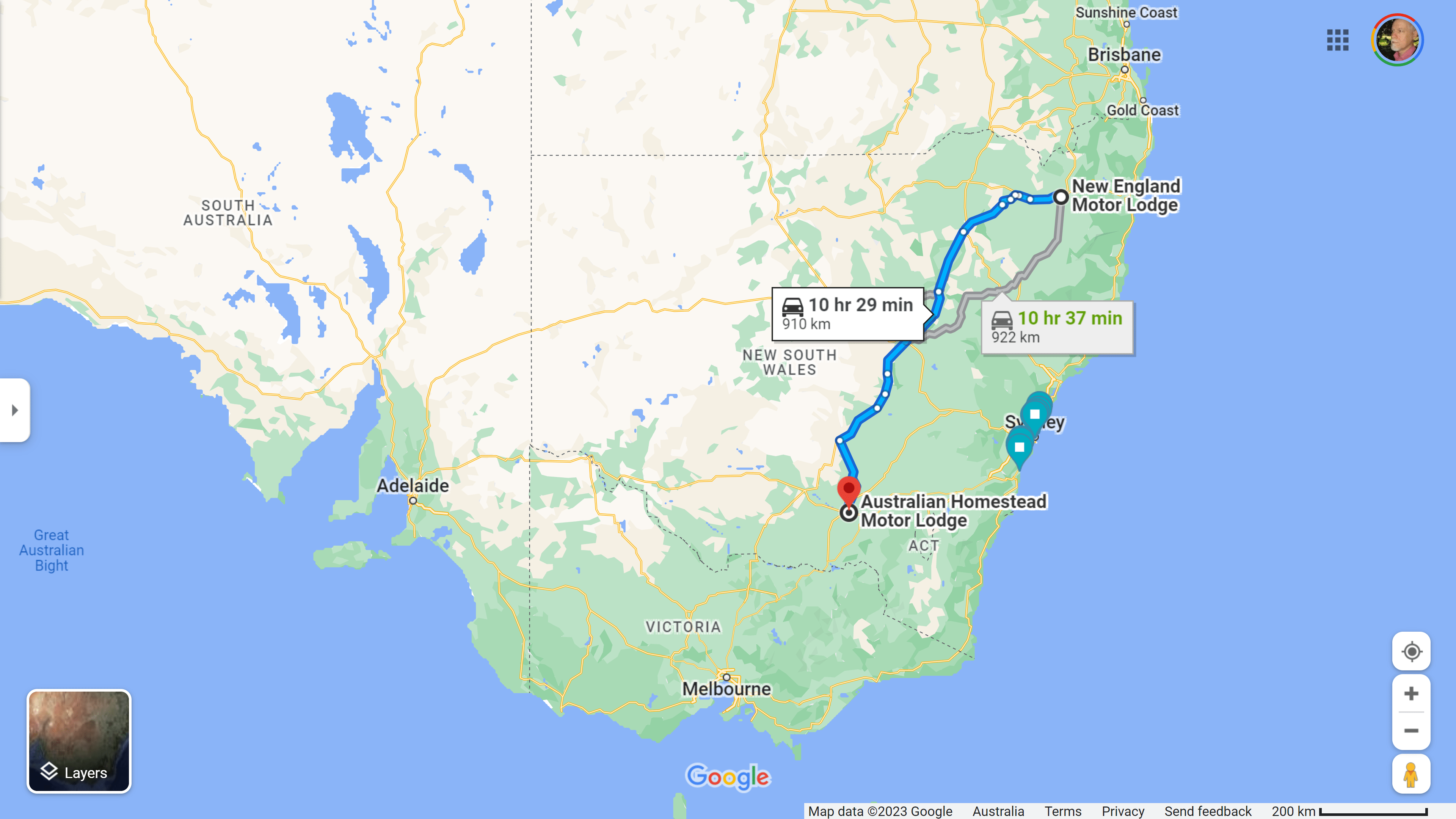

In the early morning, before dawn broke, I dreamed of how to explain my philosophy and history (historiography).

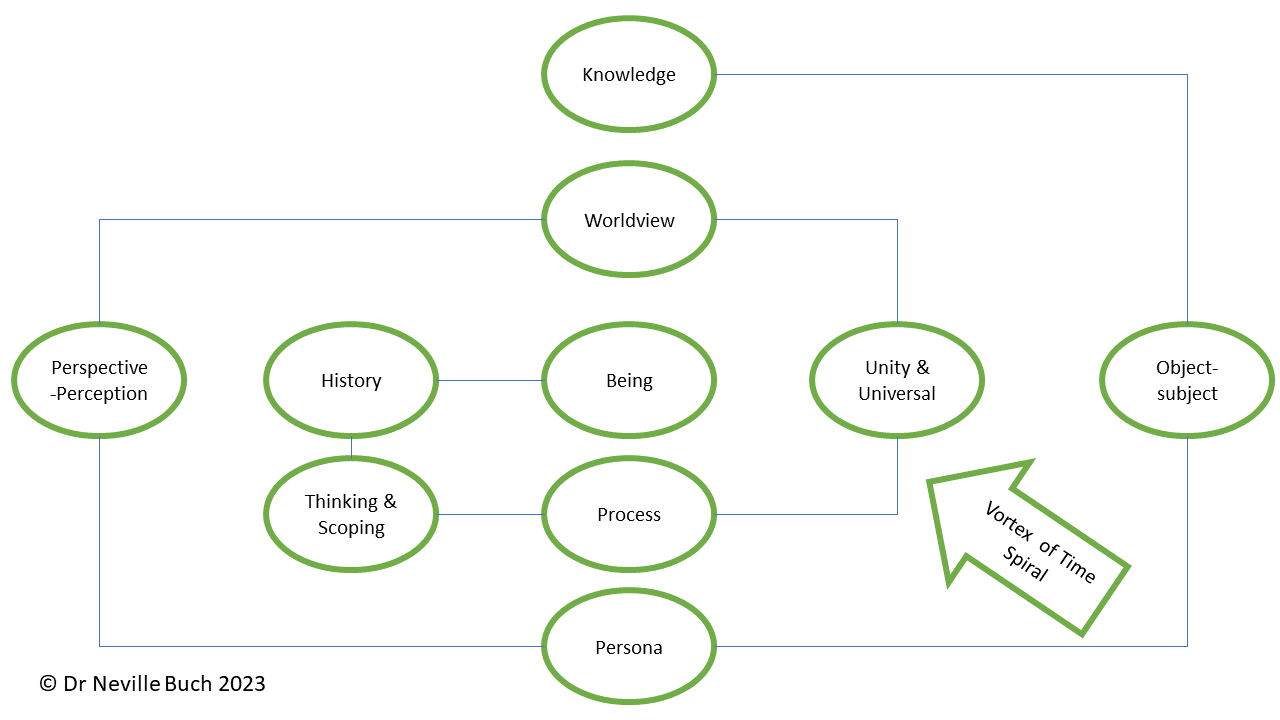

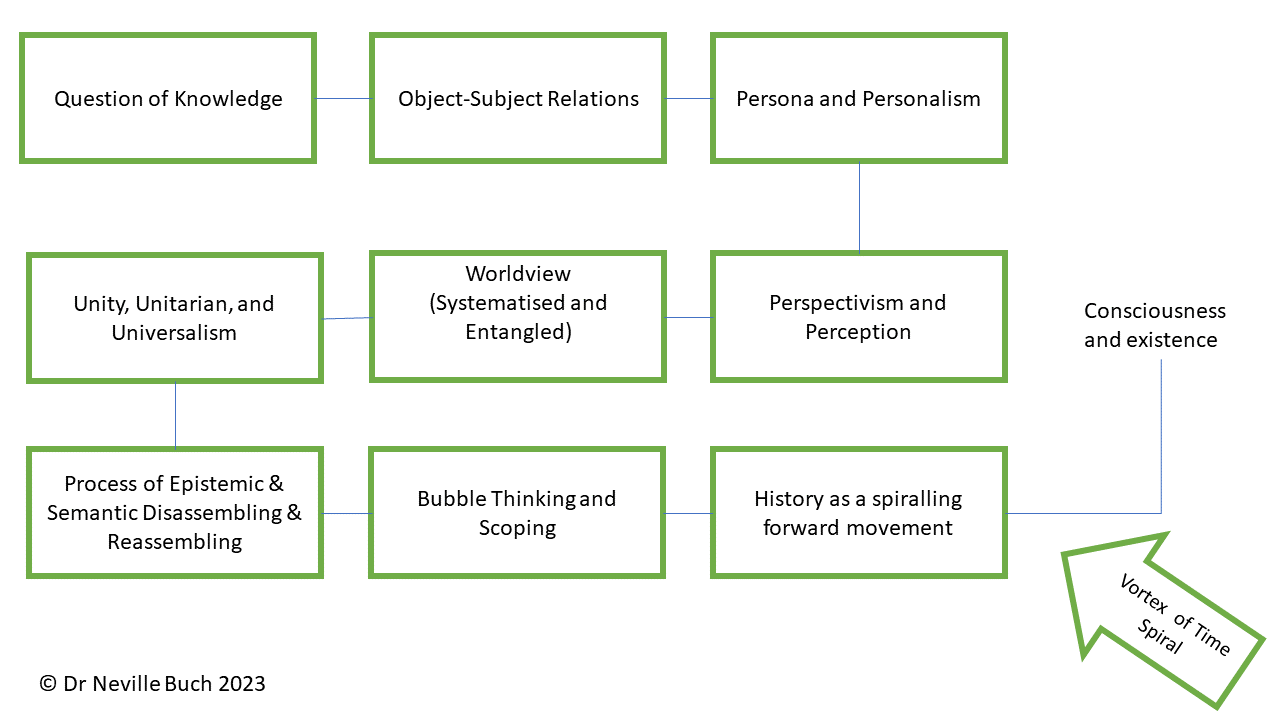

It came as my mind recovered from the slightly-over twelve-hour drive from Glen Innes to Gumly Gumly, just outside of Wagga Wagga; no, for the non-Australians, I am not talking in tongues. These are real named places. The physically distance is a little under 1,000 kilometres (621.3 miles). These are two objects with a subject in-between. Furthermore, the places are physically real. The names are conceptually real. The language is inter-subjective, lived in an object world of communication. This morning (10 April 2023), after the stress on body, mind, and perhaps soul (the vague spiritual connection between body and thought, between the material physics and abstract thought), I can close my eyes and I see the long road before me, in motion. This is the imagination of the real world, but it is not normatively how we experience reality. I lived a day on the road drive, and now I imagine it, or recall it. The recall of memory is, however, entangled. It is imagined, and thought to be re-imagined from the past experience, which is now conceptualised as personal history. It is not imagined in the way that the process was originally experienced. Already, in a matter of a short number of hours, there has been a process of disassembling and reassembling in the brain (material) / mind (abstraction). On these journeys, I use a dash camera. When I download the video segments to the PC, the images are very different to when I close my eyes and those ‘mind images’ rush in, as consciousness.

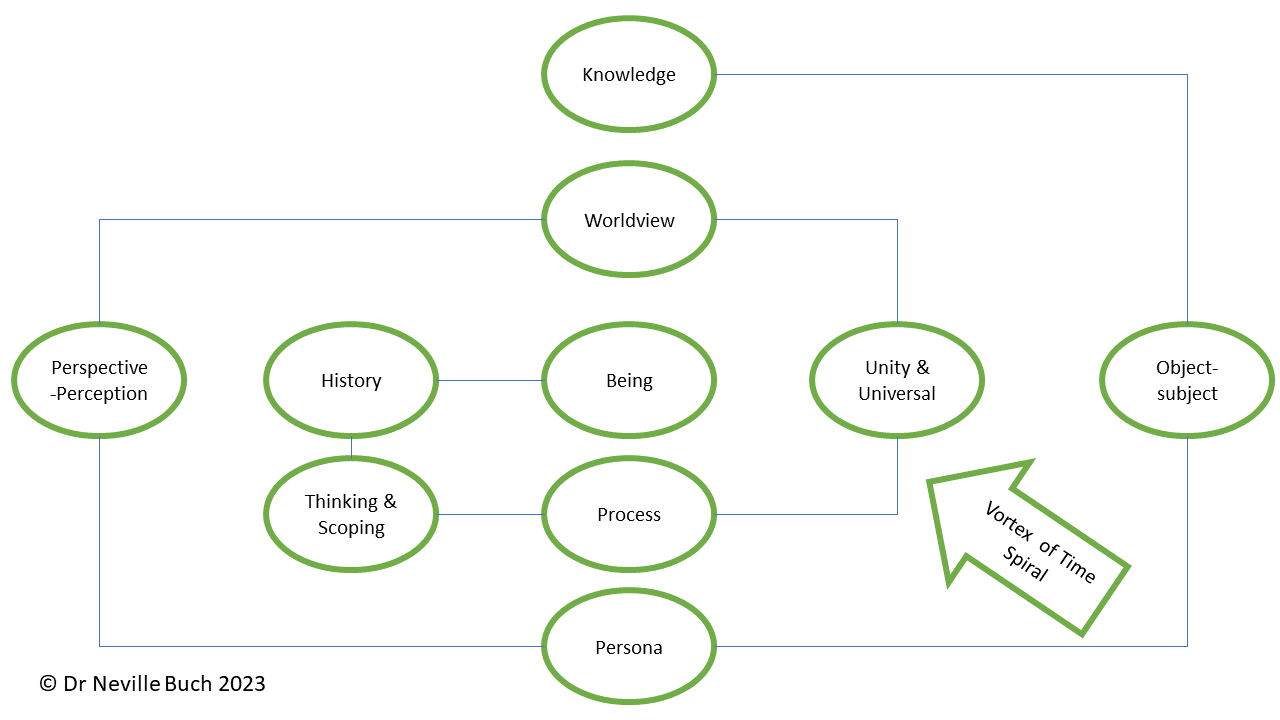

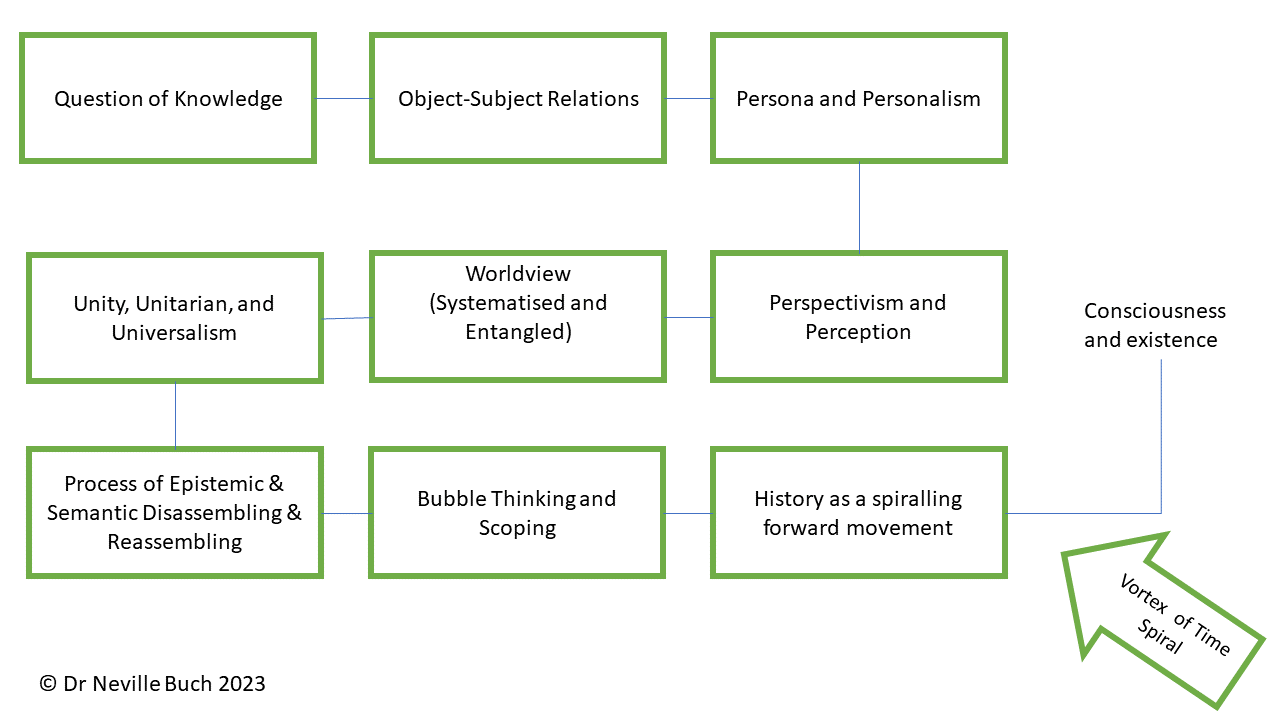

In what was explained in the above paragraph are a number of steps in philosophy and history. It is not necessary to follow those steps in the exact order of my overview below, however, there is sense to my mind in how they flow, from asking the question of the knowledge to that existential sense of being – a self-awareness, which we call consciousness.

Knowledge is always personal, or else you’re fooling yourself, and you do not know. It is also objective, in that knowledge requires ‘reflection’ which is beyond the alleged demonstration of ‘knowledge’ in imitation or disposition.

Question of Knowledge

As Socratics shows, the conversation begins in the question of knowledge. Epistemology has had a long historical journey. A few hard-headed postmodernist thinkers believe that the journey has come to an end; replaced by imagination or fragmented stories. They are in their own world of fantasy here. The more you listen to them and their reasoning, the more you realise that their explanations are the very small bubble thinking of egoism. The bulk of the population gets-on in a very connected world of the object-subject, and of the real and imaginary – inclusively!

Object-Subject Relations

An object is a philosophical term often used in contrast to the term subject. A subject is an observer and an object is a thing observed. The contested matters are the relation between the two. Descartes argued that we can cut out all knowledge of objects through a process of skepticism, but it’s impossible to doubt the subject of our self (the thinking self for Descartes). There are philosophers who will argue that the relationship is not as Descartes describes in his thought experiment, nevertheless, it is a hard cynic who would argue that no relationship exists. In which case the hard cynic – doubting totally all meaning in the terms – would find it impossible to communicate an argument when there is no common semantics; we are back to the bubble thinking of egoism.

Persona and Personalism

There is a persona here for the locked-in egoist, as it is for the rest of the population. A persona, depending on the context, is the public image of one’s personality, the social role that one adopts, or simply a fictional character. Historically it relates to the idea of a theatrical mask – it is a construction of mind in presenting self to the world. Twentieth century philosophy had developed this framework as central to understanding phenomena, and it is called, psychology. Personalism, on the other hand, is an intellectual stance that emphasizes the importance of human persons. Personalism exists in many different versions, and is diversely defined across philosophical and theological movements. There is a great historical intersection here between the psychology, education, and historiography, through philosophers, such as F. C. S. Schiller, Wilhelm Dilthey, George Howison, and Max Scheler.

Perspectivism and Perception

In thinking who I am as a person, it a small step to understanding perspective and perception. Perspectivism is the epistemological principle that perception of and knowledge of something are always bound to the interpretive perspectives of those observing it. While perspectivism does not regard all perspectives and interpretations as being of equal truth or value, it holds that no one has access to an absolute view of the world cut off from perspective. Instead, all such viewing occurs from some point of view which in turn affects how things are perceived. Rather than attempt to determine truth by correspondence to things outside any perspective, perspectivism thus generally seeks to determine truth by comparing and evaluating perspectives among themselves. The list of philosophers who developed such an outlook is extensive, but importantly, Protagoras, Michel de Montaigne, Gottfried Leibniz, and, of course, Friedrich Nietzsche.

Worldview (Systematised and Entangled)

What is sustained in these thoughts is Weltanschauung, the fundamental cognitive orientation of an individual or society encompassing the whole of the individual’s or society’s knowledge, culture, and point of view. The term was first used by Immanuel Kant and later popularized by Hegel. Wilhelm Dilthey published an essay entitled “The Types of Worldview (Weltanschauung) and their Development in Metaphysics” that became quite influential. The typologies of worldview are always contested, but this matters little, in that typologies are only models with the pretence of stability. A model is being presented in this blog article. There are no final words which correctly describes how worldviews work. Furthermore, outside of the models, in how the mind actually works in its projection, worldviews are entangled with different schemas and fragments of ideas (or ideals).

Unity, Unitarian, and Universalism

The question then becomes how do mind-matters fit together if ideas are entangled. These are questions of unity, unitarianism, and universalism. Unifying is bringing things together, but not merely as an assemblage. The assemblage has to have fit. The assemblage must hold sustainably together – at least for some time. (western) Religion follows these schools of thought. Unity, known informally as Unity Church, is an organization founded by Charles and Myrtle Fillmore in 1889. It grew out of Transcendentalism and became part of the New Thought movement. ‘Unitarian’ is different. To be unitarian is to be for a singularity, a ‘one’. Unitarianism (1565–present) is the liberal Christian theological movement known for its belief in the unitary nature of God, and for its rejection of the doctrines of the Trinity, original sin, predestination, and of biblical inerrancy. University is different again. To be universal is to scope outwards to total inclusion. Universalism is the philosophical and theological concept that some ideas have universal application or applicability. The Christian universalism movement in the United States originally referred to the idea that every human will eventually receive salvation in a religious or spiritual sense, a concept also referred to as universal reconciliation. That idea generated into religious universalism, that all religion has largely a common groundwork of thinking. Unitarian Universalism (often referring to themselves as ‘UUs’ or ‘Unitarians’) is originally a North American liberal pluralistic religious movement that grew out of Unitarianism and Universalism. Unity, Unitarian, and Universal are the great schemes of the epistemic and semantic ‘fit’.

Process of Epistemic & Semantic Disassembling & Reassembling

In these acts of Unity, Unitarian, and Universal fitness is the process of Epistemic and Semantic Disassembling & Reassembling. A process is a series or set of activities that interact to produce a result; it may occur once-only or be recurrent or periodic. Process philosophy, also known as the ontology of becoming, or processism, is an approach in philosophy that identifies processes, changes, or shifting relationships as the only real experience of everyday living. There is a long list of philosophers which demonstrates the stupidity of egoists who frequently dismiss process philosophy as nonsense, and these philosophers includes: The Buddha, Heraclitus, Friedrich Nietzsche, Henri Bergson, Martin Heidegger, Charles Sanders Peirce, William James, John Dewey, Alfred North Whitehead, Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Iain McGilchrist, Eugene Gendlin, Thomas Nail, Alfred Korzybski, R. G. Collingwood, Alan Watts, Robert M. Pirsig, Pierre Teilhard de Chardin, Roberto Mangabeira Unger, Charles Hartshorne, Robert Cummings Neville, Arran Gare, Nicholas Rescher, Colin Wilson, Tim Ingold, Bruno Latour, William E. Connolly, Gilles Deleuze, Alain Badiou, and Arthur M. Young, and so on, and so forth. The thinking involves disassembling and reassembling ideas from the entangled worldviews. However, nothing is put back the way it once was perceived as a past worldview. In other words, learning occurs and there is a change in the outlook from the dynamic thinking. In the process epistemology is as important as the semantics.

Bubble Thinking and Scoping

So, why does the thinking go wrong, and produced the common entangled worldview? The article has already suggested an answer to the question in the boundaries of egoism, and this should be called, bubble thinking; an inability to think outside of a bubble thought. In logic, the scope of a quantifier or a quantification is the range in the formula where the quantifier ‘engages in’. In the formula ∀xP, for example, P (or xP) is the scope of the quantifier ∀x (or ∀). In simpler terms, to ‘scope’ is to judge an extension of the knowledge, and a decision can legitimately widen the circle or narrow it. The problem is that egoist’s scope is always too narrow for questioning knowledge and finding adequate answers.

History as a spiralling forward movement

In the whole model presented is movement; a movement of time as conceptualised. That the idea of time is contested is not a matter of consequence. Excluding those with timeless sense, and we all have those moments, we commonly live our lives forward: past, present, and future. This is not necessarily a linear historiography, and, in fact, I am arguing that it is not. It is a sense of time, or construction of time, as spiralling. All of these thoughts result from constructivist epistemology and semantics. We cannot reproduce as a digital video camera the motion of reality; however, our imagination reproduces as a mind construction, disassembling and reassembling ideas from the entangled worldviews, which emerged as lived experience.

Consciousness and existence, and the Vortex of Time Spiral (concluding thought)

It all comes back to life, and the questions of what is consciousness and existence, and who am I as a human being? We all have personal histories which need to be respected, not knocked down by the “asshole” egoist in the self-hatred. We currently living in such an anti-personal-history world with the silly arguments of European ‘right to privacy’ and the ‘end of history’, and of the Trumpian ‘my country right or wrong’ (and much more wrong). The idiocy or stupidity is the dismissal of abstract thoughts from other persons. Knowledge is constructed by the philosophers. To say you know and dismiss the abstract thought without understanding the philosophers is the definition of idiocy or stupidity. You do not know and yet act as if you do know, but that is acting falsely in the world.

And it is time we call out this nonsense, truly, as we all hurdle into the vortex. Time to get back on the road journey of life.