by Neville Buch | Nov 4, 2022

The Cultural Influence of the 1970s Mainstream Evangelical Conservatism

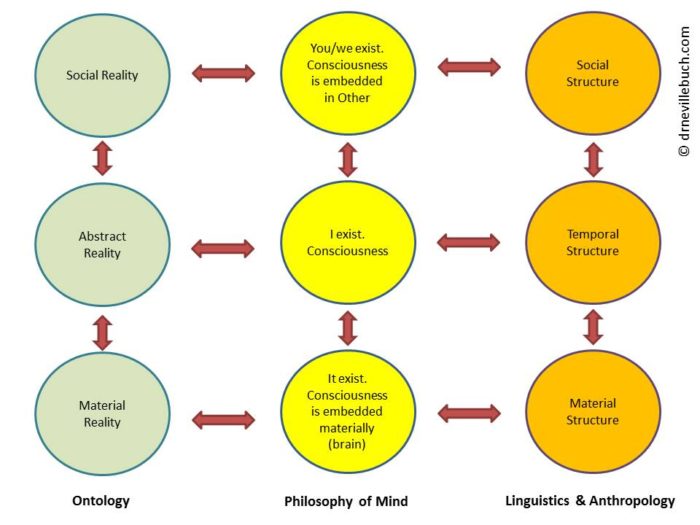

In the previous essays the organisational history of Teen Challenge Inc. has been described under the activities and intellectual headings of ‘evangelical outreach,’ ‘Christian community’, and ‘social work’ with both secular and sacred regard for the person.

Organisational Teen Challenge Inc. workers across the timelines represented the thinking, collectively, of the triangular thinking of the mission, commune valuing, and working for a better, improved, or transformed society.

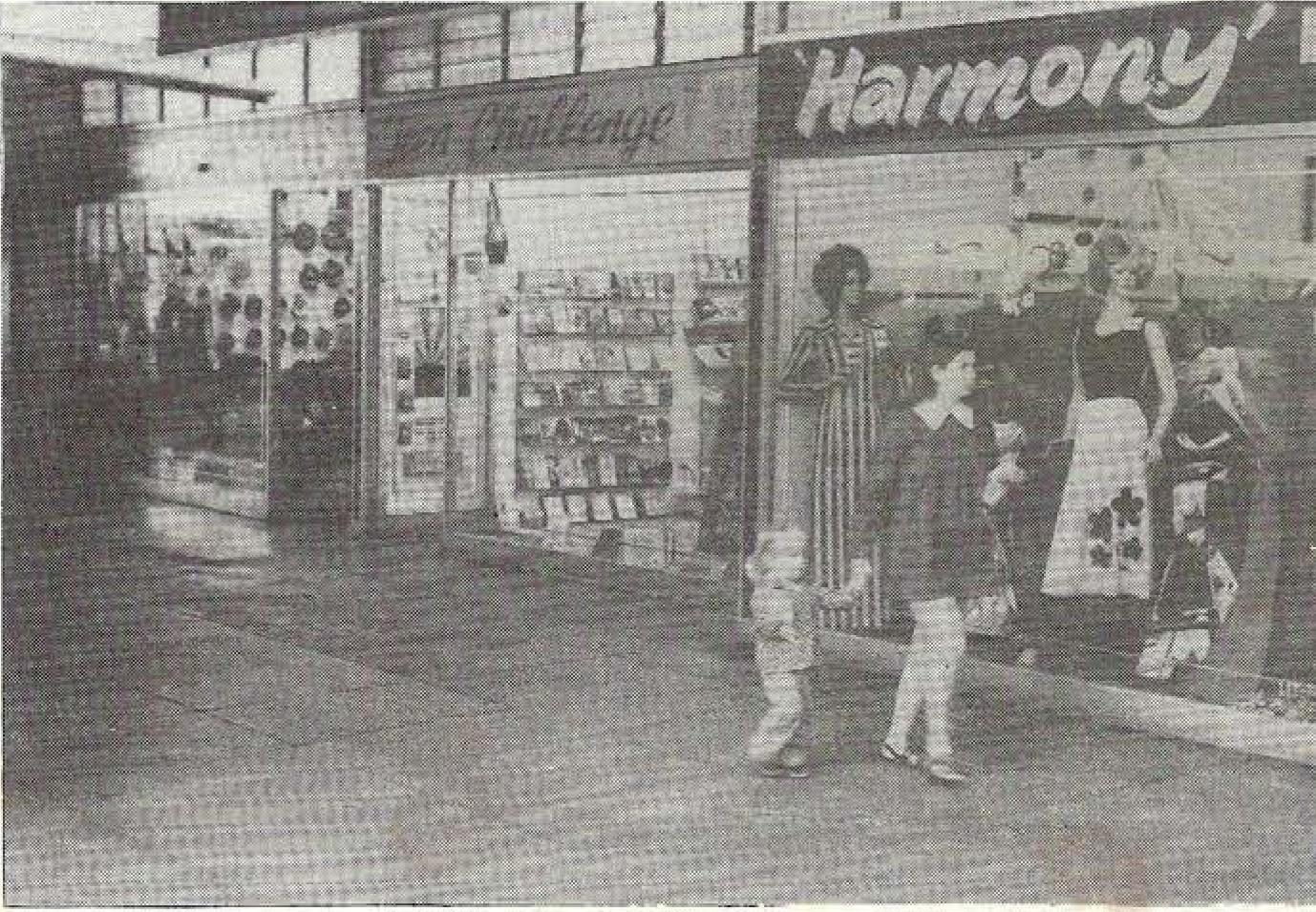

Figure 1. Teen Challenge Inc., Enoggera Terrace, Red Hill. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

To take a snapshot of the early days of the Teen Challenge Inc. Office, from circa 1975 to 1984, at the Woolworths Shopping Centre, 107 Latrobe Terrace, Paddington (QLD 4064). It was a centre-point in time, coming from a location usually describe in the earliest years (circa 1974-1975) as located at Enoggera Terrace, Red Hill (QLD 4059). It would have been the third ‘Head Office’ following Newmarket and South Brisbane and combined with the Rehabilitation Home at the same address. The confusion of locations might be simply a matter of suburban boundaries, but there is more at play. There is a time shift here, and there is the common geographic confusion for common office workers, possibly stuck at their desks much of the time, and/or lacking good knowledge of their surroundings. The previous office site, up to circa 1975, was Newmarket ‘around the corner’ from ‘Enoggera Terrace’ in Enoggera Road (Confusing?). One of the hardest lessons for Christian missions is understanding landscape and understanding persons in landscape. Memory is not good enough to interpret the past and testimonies need further examinations.

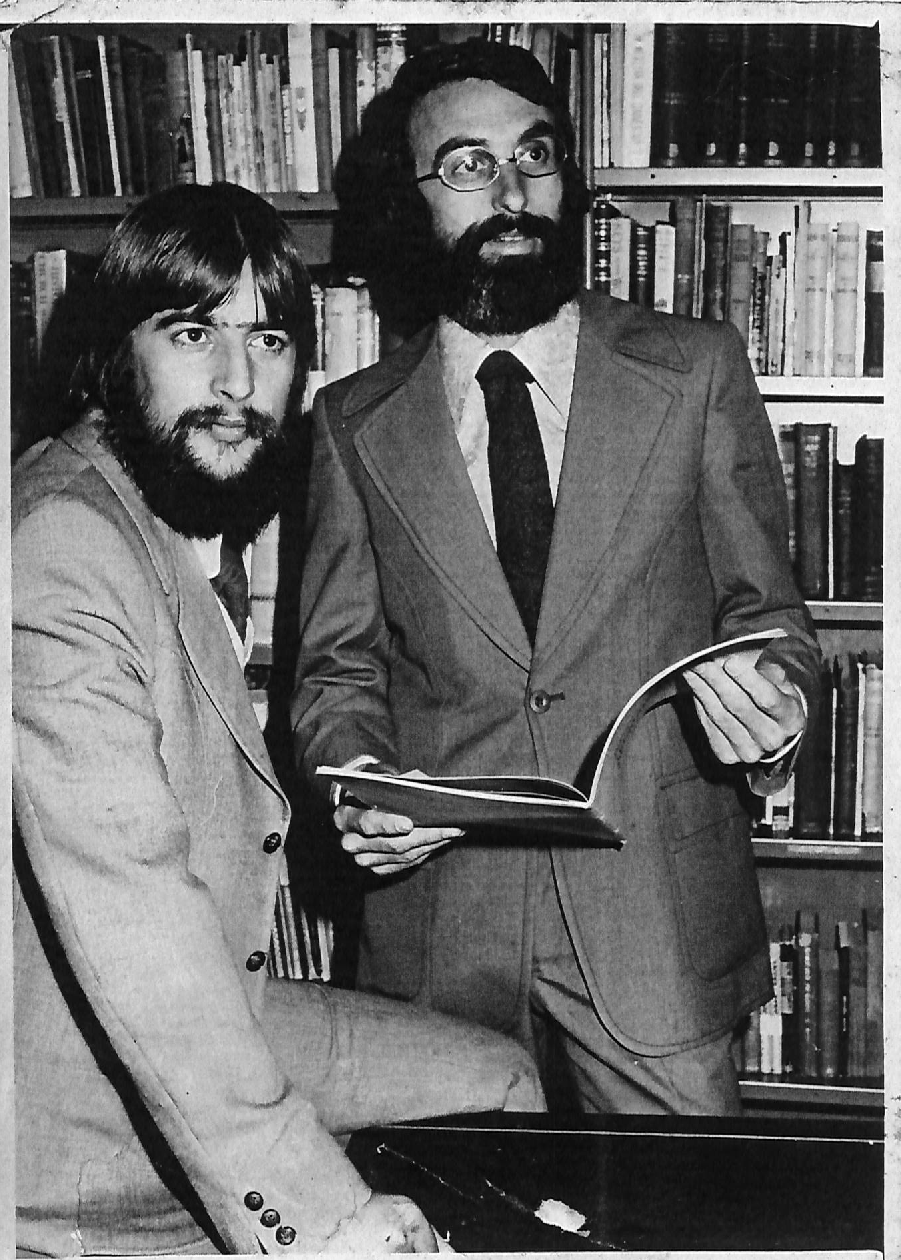

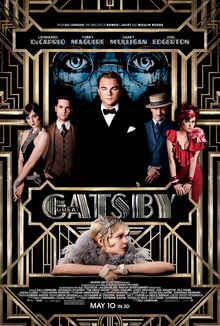

Figure 2. The Teen Challenge Bookshop, Newmarket. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

With Charles and Rita Ringma, mission is a driving force among the office workers. The Office was run in these days by John and Pat Healey, who came to Teen Challenge Inc. as workers of Youth With A Mission (YWAM). YWAM had a much stronger ethos of discipleship and evangelism than many other of the similar organisations in Brisbane. Among the YWAM literature there was a revivalist crusade theme, lacking a certain critical edge in the far more socially conscious Teen Challenge Inc. There were other early Teen Challenge workers who shared the same rough street preacher approach.

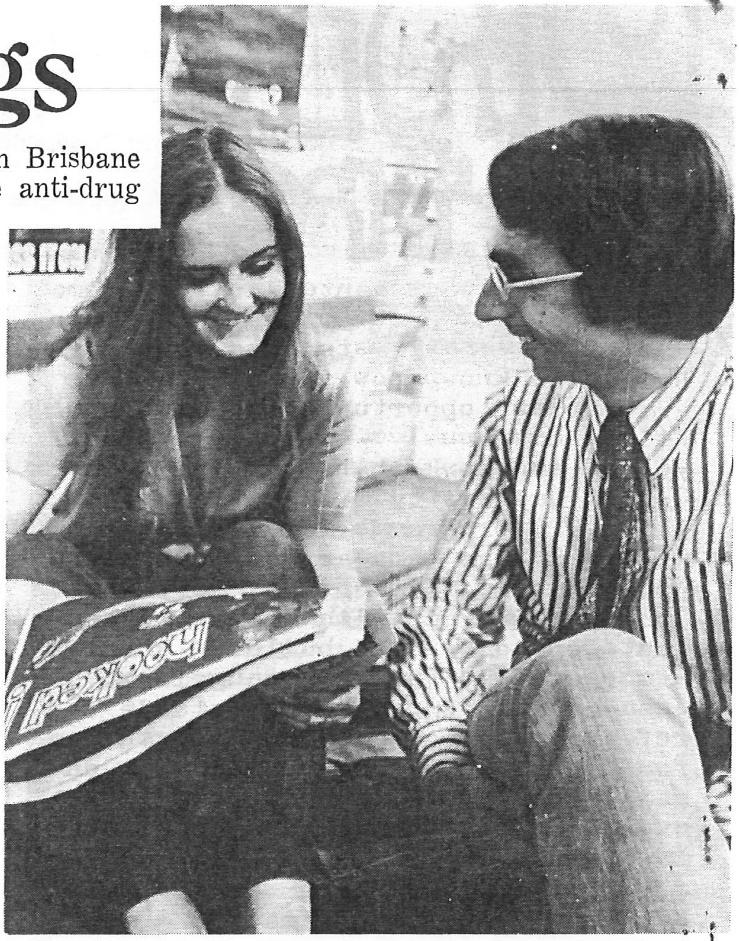

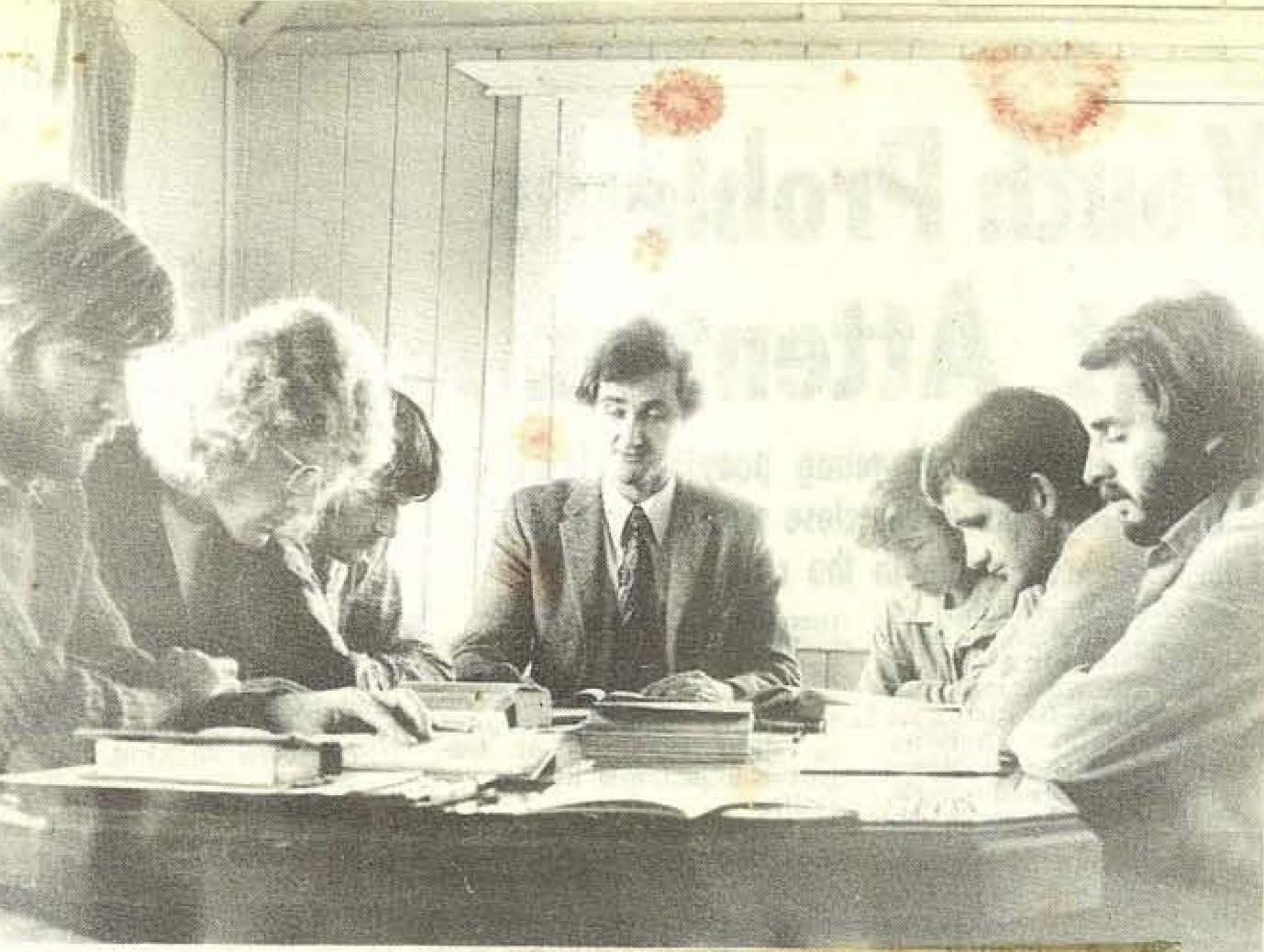

Figure 3. The Early Teen Challenge Inc. Office. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The Organisational Issues of Financial Philosophy and Strategy

However, Teen Challenge Inc. was a business from day one. The fourth area of the organisation was financial philosophy and strategy to keep the business running,

Much of that work was the role of the Board of Management, and, in the early days, Board members needed to have a more hands-on approach in the Office. Henry Baskerville was the first Treasurer, for the Board of Management, Teen Challenge Inc. He was the finance man with one foot in sacred space and the other in the space for secular operations. He was the Manager at the Newmarket Commonwealth Bank, and also Vice President for Gideons in Queensland. Next came Albert Hall who formally took up the title of the Office Administrator, working closely with Charles Ringma as the Executive Director. Albert Hall was also a Board member and with his secular work connections, the Board in those days met at Shell House, Ann Street in the City (QLD 4001). The role of the Board Treasurer and Office Administrator, whether the same person or not, was as a financial advisor/bookkeeper.

Ringma modelled his directorship from Bob Bartlett, Director, Teen Challenge Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America. Around Charles was a team of personable directors for different divisions of the organisational work. John Healey was the Acting Executive Director, delegated as Charles’ representative. Other Office Administrators worked in the Office in the same period, Peter Jones with Brenda Jones as an office worker, and Dennis Everett. Geoff Job was a Centre Supervisor and an office worker, with Cathy Job as a Secretary.

Office workers were conflated as volunteers and stipend paid workers. Full award wages were unheard of in the charity organisation, and it was only Christian trust that keep this small business economy going. The workforce was not unionised, not by principle but by economic necessity, and kept running by the worker’s own professional pro bono attitude. In the last half century, the arrangement has reached a critical point, with the economy being little more than the worker’s self-serving slave labour. The fact is well recognised in the industry, but conservative governments wish it away.

The Organisational Issues of Governance and Administration

The Incorporation of Teen Challenge in Queensland in 1972 would have meant that the organisation had, at least, one Legal Advisor. What is known is that Board member Graham Corney was a solicitor.

Council of Reference

The Council of Reference might have been for show, a process of legitimatization. It did not last long, and there is very little information on the Council, except for who the members were. There were media personalities, one type of showmen. Reg Leonard was probably the most powerful figure. At the time he was Chairman (1971-82) of Brisbane TV Ltd, but he held Chairmanships and Board membership across the Australian media world. Former Church of Christ minister in Annerley, Hayden Sargent started his media career at the Christian Television Association. In those days of the 1960s, he hosted a daily half-hour program, Look, for Brisbane channel TVQ0. In these early days of the 1970s, he ‘pioneered’ local talkback radio at 4BC. He also hosting a daytime talk-back television program, Heartline, produced by Reg Grundy in Brisbane for the Seven Network, and would later hosted local current affairs programs Haydn Sargent’s Brisbane for BTQ7, This Week for QTQ9 and The Sargent Report for TVQ0. His recommendation for Teen Challenge carried much local weight.

There were a few medical show-persons on the Council of Reference, political operators. Arthur Crawford had the third biggest surgical practice in Queensland, it is thought, in the late 1960s. However, his role in the long history was as the Legislative Assembly member for Wavell (1969-1977) for the Liberal Party, and in that parliamentary role a loud and harsh critic of the State Health department and of the socialised medicine. Such a loud critic’s support for Teen Challenge meant that the organisation could overcome the skepticism in the medical profession. Crawford was joined on the Council by Phyllis Cilento. Another controversial figure, the grand old lady doctor, who did had a much softer demeanour than Crawford. Cilento was the conservative progressivist for maternity and child health reforms. Her controversial reputation has returned in recent times. With her famous husband, Ray Cilento, she spoke in very white-centric terms. Although she did not have the outright racism of Ray, as it is contemporarily considered, the naive motherly adornment for racial hierarchy is little tolerated today.

There also academics and associates of the academy among the Council members. The most noted, as an academic career, was Paul Wilson, and yet to be another controversial figure. A criminologist at the University of Queensland, and later Bond University, he would be found guilty of four counts of indecent treatment of a child under 12 years in 2016 from child sex offences (allegedly) committed in the early 1970s. This was an era that Wilson was writing on policing and criminal law courts from a social justice perspective. Hypo-conservatives are extremely unhappy with these exposures from historians. Historians, those good at the profession, breaks the illusion of the good-bad binary. Unfortunately, there are readers who are want the ‘great comfort’ and seek ethical understanding in such traditional and conventional theology, which does stand up to the historical scrutiny. Again, fallible persons in the landscape must be seen. This is no less true for Teen Challenge Inc.

The rest of the Council members were still being called ‘men of the cloth’ in the early 1970s. The Rev. Dr. Charles Geoffrey Noller was an academic associate with his wife, Patricia Noller, an internationally renowned professor of psychology. Charles and Patricia Noller came from New South Wales for Charles to become the Director of Lifeline Brisbane in 1971. From his career in LifeLine, Noller became involved in Legal Aid, Drug Arm, and the Family Council of Queensland. He also became a teacher in the short-lived interdenominational Brisbane College of Theology. Most of these local religious ‘showmen’ were well-known to each other in the small township mentality of Brisbane. It is not a negative criticism, but a factor in personality type. Religion is theatre and it is performance.

On the scale of the religious hierarchy among the Council members was Felix Arnott. Archbishop of Brisbane from 1970 to 1980, the highly educated Arnott was the closest thing Queensland Anglicans had as a public intellectual, and, as such, the churchgoing ‘ratbags’ regarded him as a dangerous theological liberal. Much of the criticisms of the hypo-conservatives was socio-political, although that could not be admitted. The height in the discord arrived in Arnott’s role as a member of the progressivist the Commonwealth royal commission on human relationships. At the annual diocesan synod in June 1978 Arnott decried against the erosion of civil liberties in Queensland, and, like Charles Ringma and Noel Preston, endured the self-righteous wrath of the Nationalists.

The Protestant mainstream in Queensland were moderately liberalising Christian believers, as were the remaining two members of the Council of Reference, Rev. Gloster Udy and Rev. Dr. Lew Born. Gloster Udy was a Director of Lifeline and would during his career served on the staff of the General Board of the Methodist Department of Evangelism in Nashville. Lew Born is a lesser-known figure but as Director of the Methodist – then also Uniting – Director of Youth People/Christian Education he was highly influential in a soft evangelicalisation through the camping movement.

The Council of Reference was brief in time and does not appear to have done much. However, in starting a progressivist enterprise in the early 1970s, it was important to have the Council of Reference as a ‘showboat’ from the high society Felix Arnott to the ‘touch-of-the-common man’ Lew Born. From the backroom power play Reg Leonard to the motherly Phyllis Cilento. It calmed nerves in the pews and installed confidence across radio and television.

Board of Management

The real power for Teen Challenge Inc., in terms of setting directions and capabilities, was in the hand of the Board of Management. Many of the members of the Board have been referenced across the essays. The dominance of the Assemblies of God has been noted – Rev. Ralph Read and Rev. Gerald Rowlands, with Charles Ringma, are at the top of the list, joined by F.G.B.M.F.I. Keith Kelly, Pastor Gary Swenson and Pastor Roy Short. The Board’s moderating voices to this Neo-Pentecostal outlook were Methodist Minister Wal Gregory, Presbyterian Minister Harvey Pollock, Church of Christ Minister Ted Watson, Chartered Accountant Don Usher and state public servant Gary Uhlmann.

The Organisational Issues of The Outreach Issues Including Ventures and Tours

As in all humanity, Charles Ringma had/has different parts of his personality. The personally of an AOG minister is the work in the concept of outreach. The lost become saved and are brought from the street into the ‘temple’ – middle class church congregations. It is more than a fishing exercise but, at its basics, this is what outreach is. This was the reason why Charles was reluctant to start Jubilee Fellowship. He had hoped that Teen Challenge converts would be integrated into the established churches; theologically, this is understood as sanctification. Culturally, the old Catholic doctrine of there being no salvation but as the Church (Body of Christ) became there are no true Christians except on the cushioned seats of the Megachurch. The lives of the young converts changed the lives of Charles and Rita. The counterculture thinking never disappeared by the time Jubilee Fellowship became an ‘established’ and regular congregational gathering. Charles, over time, articulated polite institutional critiques in his writings, but under the politeness the majority of Jesus-informed Christians believe that the Church (institutionally) had betrayed Jesus Christ, the son of God.

In Christian literature that critique is becoming more forthright, over the last half century, and openly defiant since the betrayal of the Evangelical Right in the Trump era.

AOG Branches

There was a period of hope for AOG churches in the late 1970s and the 1980s and 1990s. For a quarter of century, AOG churches were active in Teen Challenge Inc. with official branches in regional centres. For example, among the early TC branch leaders centred in the local AOG churches were Berend and Moss Boer, the Townsville Contacts; and the Pauline Peake, Toowoomba Worker.

In the era before the Charter Towers and Toowoomba physical facilities, this was the only way that Teen Challenge Inc. could achieve regionalisation.

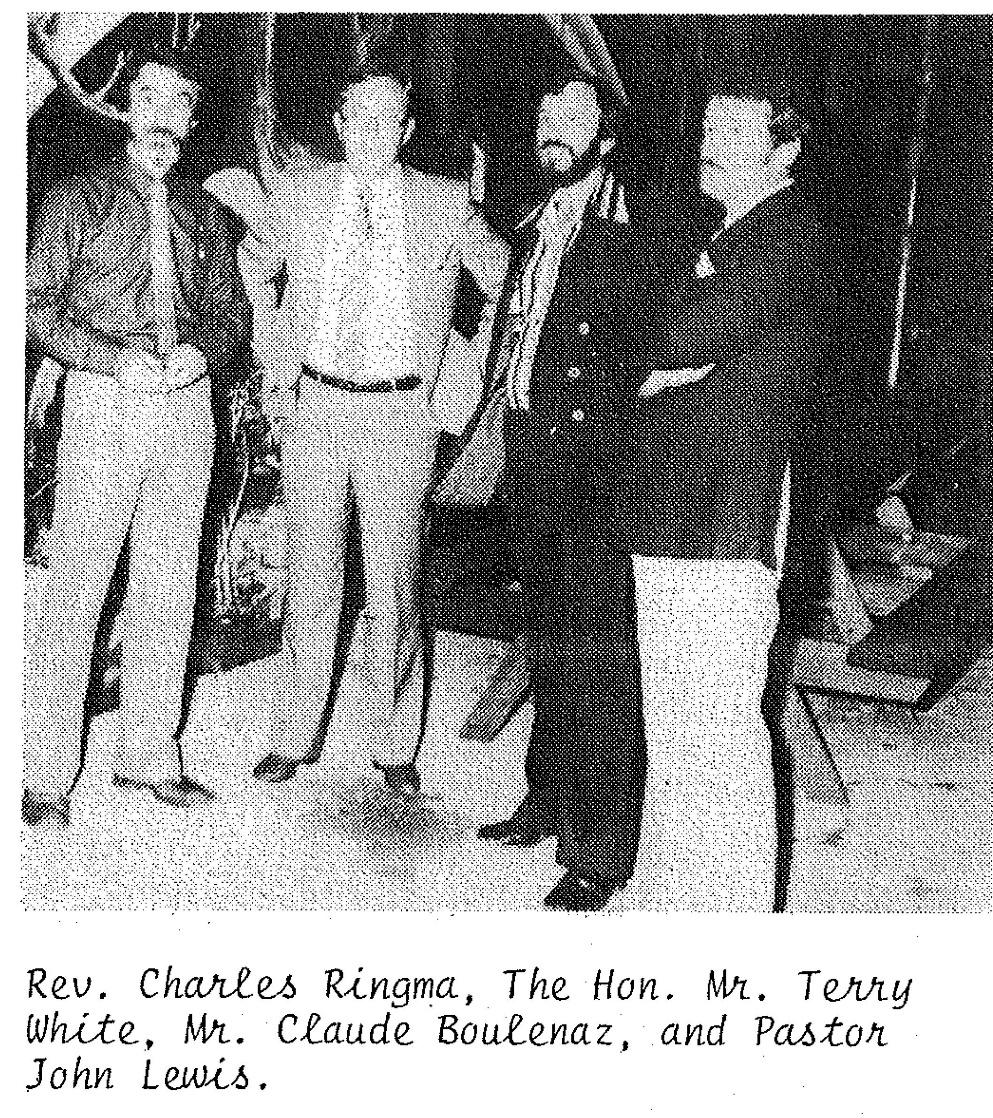

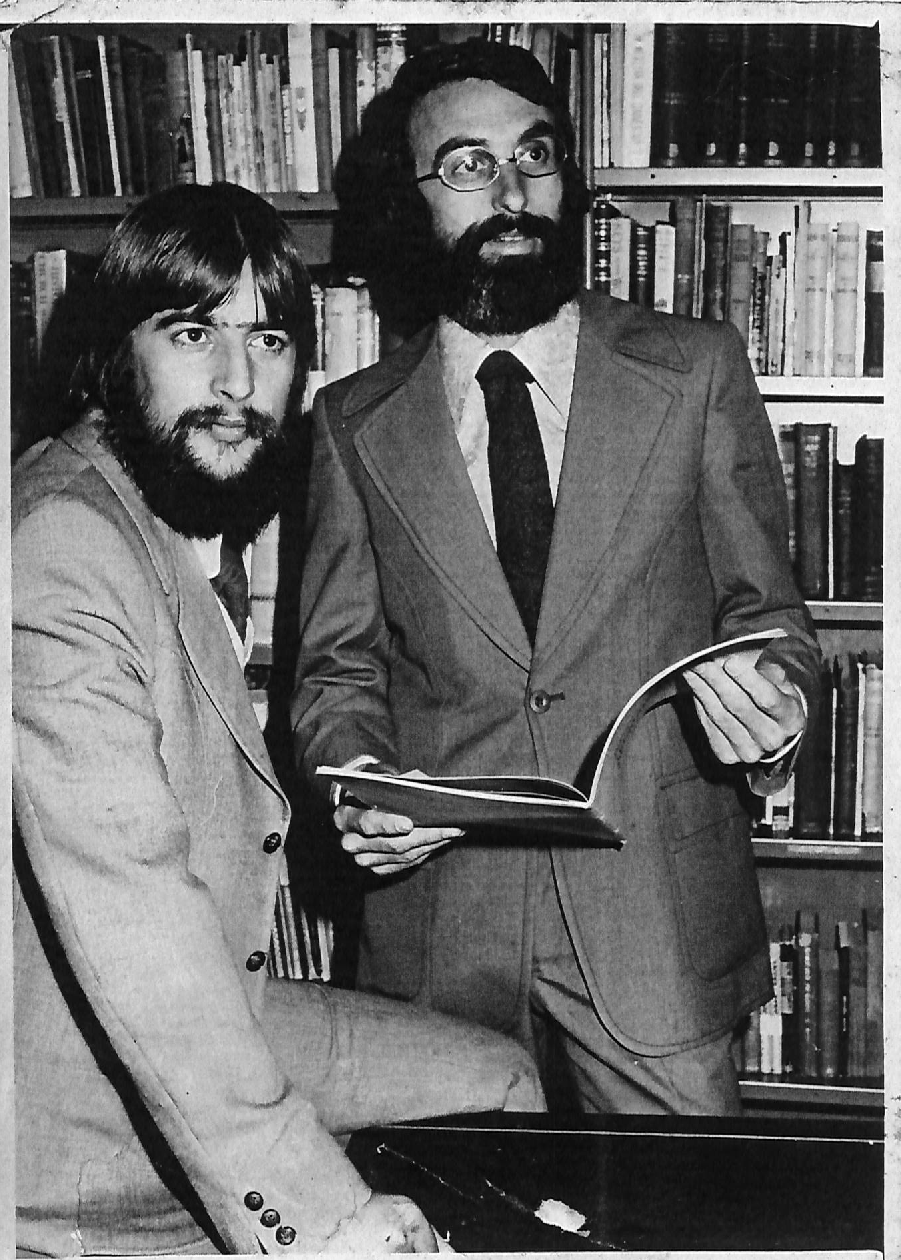

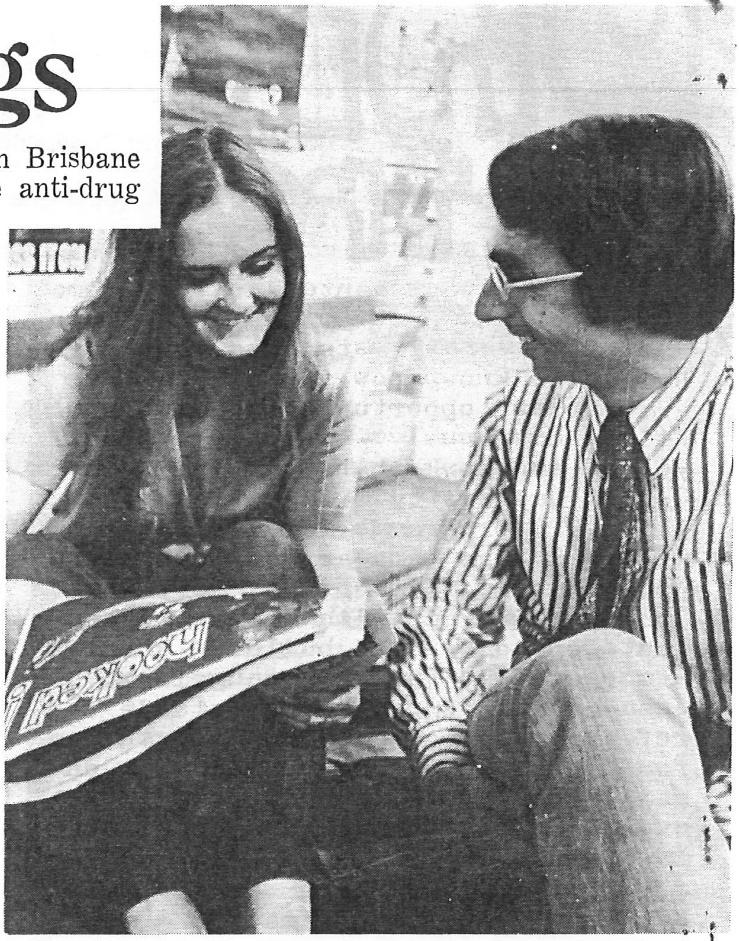

Figure 4. Teen Challenge Inc. Folk, circa 1974. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The Organisational Issues of Activities of Media, Rehabilitation, and Education (Prevention)

The activities of Teen Challenge Inc. across time and space can be explained under the organisational headings of Media, Rehabilitation, and Education (Prevention).

Figure 5. Discussing Teen Challenge Promotion in the Office. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Media

The point has been made above that those members of the Council of Reference were showmen and show-woman for Teen Challenge Inc. We have also seen Board members, particularly the ‘men of the cloth’ were also performers. Hadyn Sargent was not the only local radio and television personality to promote Teen Challenge. Chris Adams, a local radio personality, was one of the early office workers. His role was in developing a publicity program for the organisation.

Media is an important feature of the counterculture. It has to out-message the mainstream. The centre of operation was there in the beginning, in 1972, called, Jesus People Action Groups, with the P.O. Box 88, South Brisbane 4101. These were the days when the bulk of communication came as paper-based letter writing. The early Teen Challenge Inc. periodicals had different titles, starting with ‘Rag Writer’. They were typed and wet-print duplicated two or four sheet newsletters or rag newspapers. Undergraduate-orientated hand-produced comics dominated the visuals. Charles Ringma was the Editor, Philip Horwood was the Layout Artist, and Delene Lancaster the Typist.

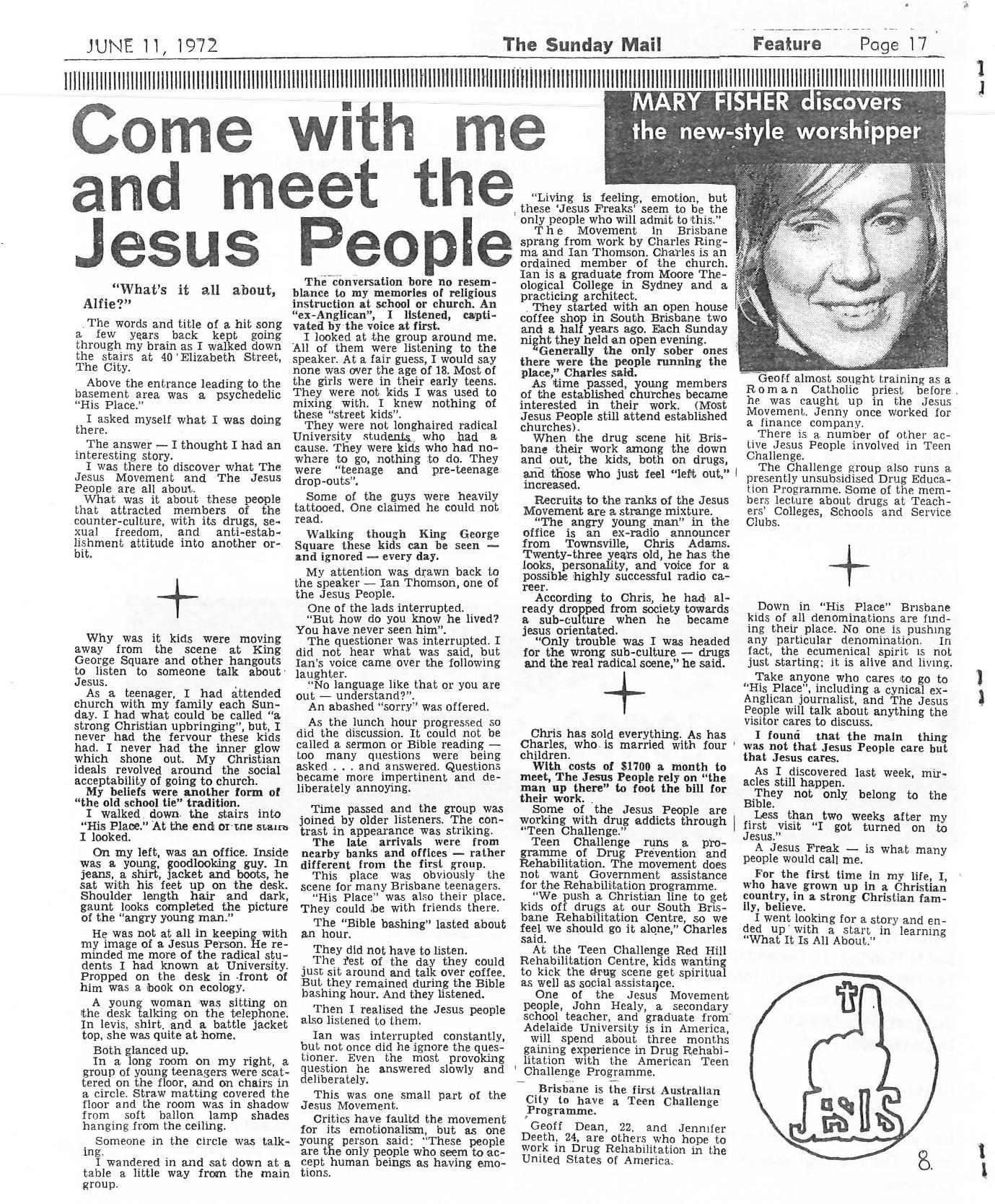

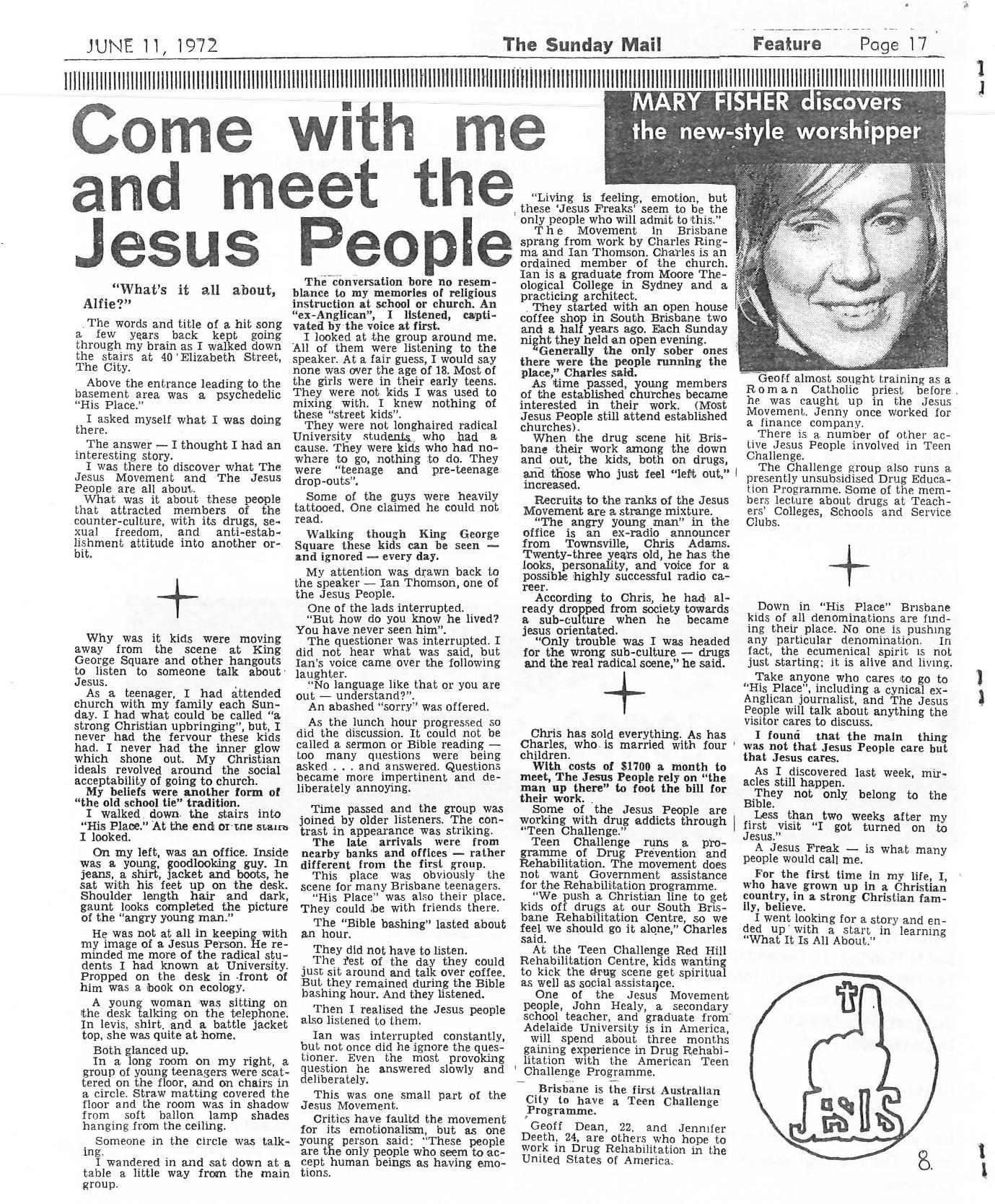

The Queensland News Corp began to splash several articles on Teen Challenge, usually on a first section page in its dailies. The role of Reg Leonard has been noted as a significant figure, a TC ally who headed up a media empire in these days of diverse media ownership. Of the articles the most transformative was that of Mary Fisher, a Sunday Mail Reporter. Fisher explains half a century later:

“When I wrote that first article on Teen Challenge, The Sunday Mail gave me a major ‘by-line’ on the front page of the Features section. This is the photo that went with the ‘by-line’. It was a week before my 24th birthday.

Up until then the editors had not been impressed, in fact very unimpressed by my writing.

That was the day they later referred to as my becoming a good writer.

I believe it was our Lord enabling me.

I have so much to be grateful for.

So grateful

Love in Christ”

The Teen Challenge narrative was transformative on the newspaper pages in 1973-1974 when the organisation was fresh news. That continued for some time, but it could become a double-edge sword, as when in 1977 Charles’ image was ‘front page’ news, among a group of clergies who opposed the positioning of the Joh Bjelke-Peterson regime. Newspaper readerships are prejudicial and newspaper owners play on the prejudice.

Figure 6. The TCTI Logo, circa 1982. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Figure 7. Mary Fisher’s Ground-Breaking article for Teen Challenge Inc. in The Sunday Mail. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Rehabilitation

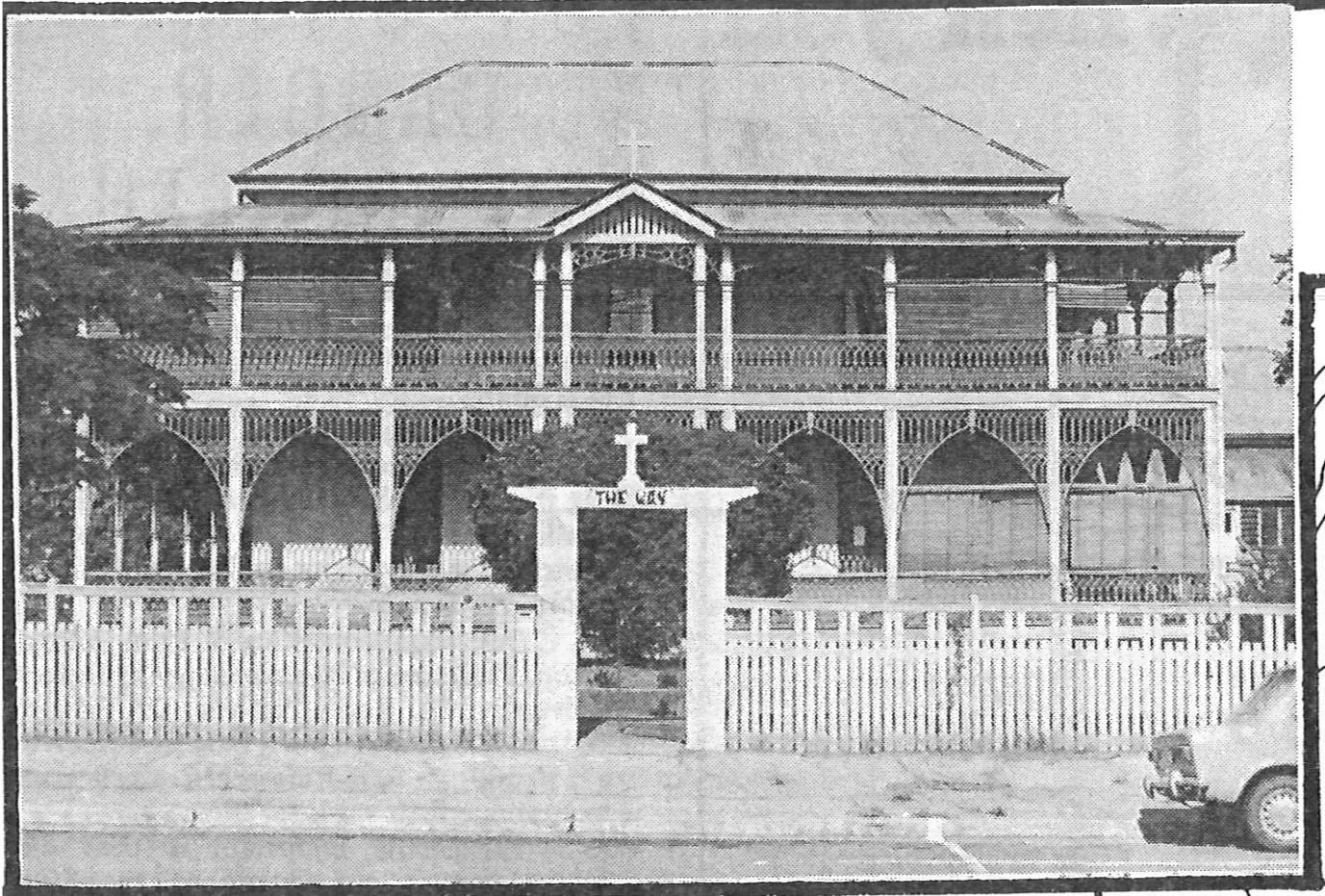

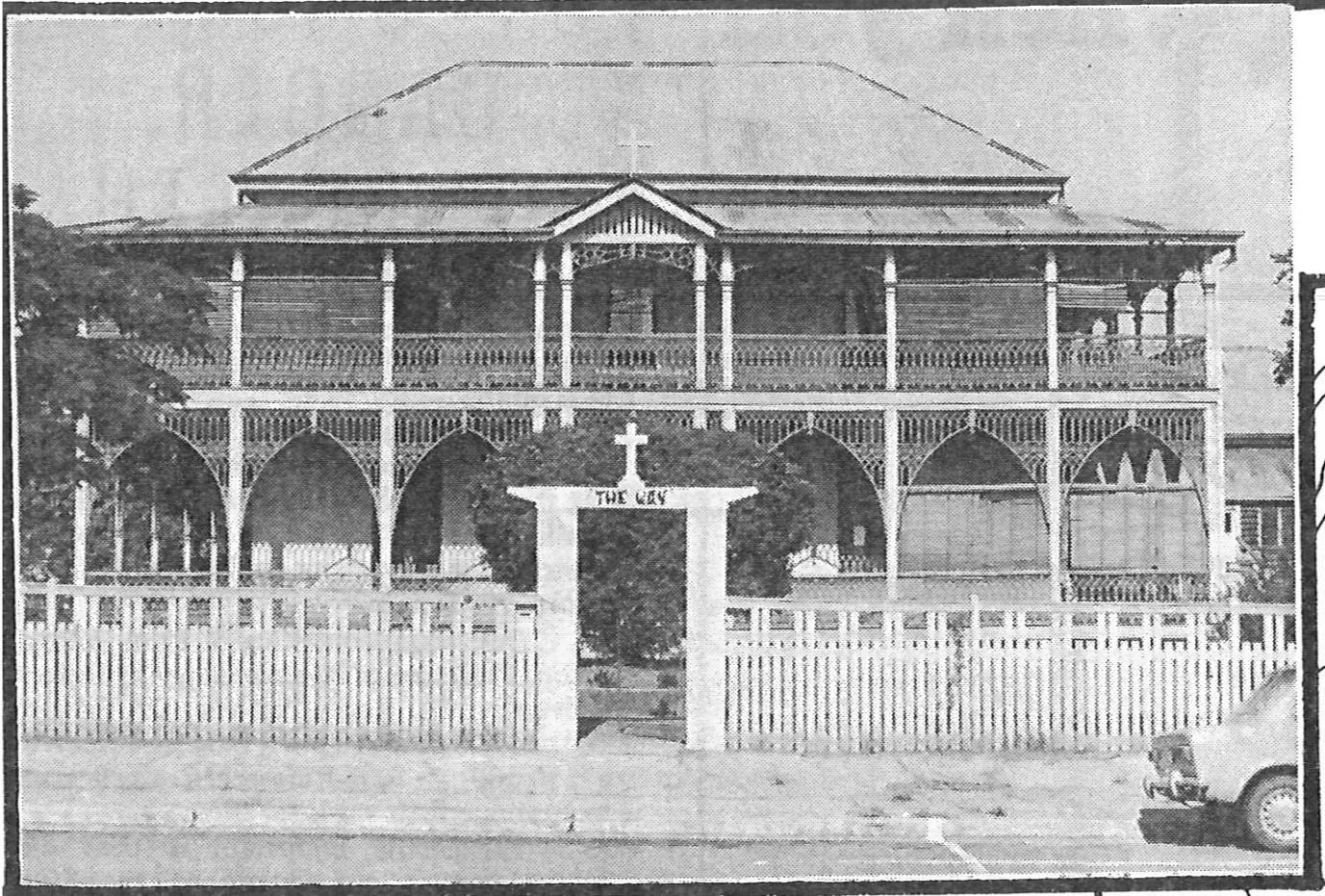

The backbone work of Teen Challenge was drug rehabilitation. The work was also heavily organisational, beginning even before 1972 with Charles Ringma as the Manager, and early residents-workers, Joyce K and Mac Campbell, for The Way Office and Outreach Residence, at 1 Peel Street (cnr. Cordelia Street), South Brisbane (QLD 4101). John Healey began his TC work as an organiser at The Way. Healey was responsible for the Open House Bar-B-Q on the 26 August 1972. During 1972 Charles and Rita moved out The Way to establish a home, as the Executive Director’s Residence, at 34 Gresham Street, St. John’s Wood, Ashgrove, QLD 4060. It operated as a second headquarters for the Teen Challenge Office. Terry Gatfield became the Director, at The Way Centre, partnered with Rosemary Gatfield, another valuable TC worker.

Figure 8. The Way (Good News Centre), 1 Cordelia Street, South Brisbane. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Charles Ringma as Executive Director, Peter Lane as Rehabilitation Director, Dot Lane and Doug Boyle as Rehabilitation Workers, had the work of the TC men’s rehab at Enoggera Terrace, Paddington; it is referred in the records as, Enoggera Road, Red Hill (QLD 4059). However, the exact location has yet to be marked in the Teen Challenge Mapping program.

In 1973 John Healey was formally appointed Teen Challenge Rehabilitation Director, Brisbane. In these years 1973-1974 there were unnamed drug rehabilitation managers and organisers across the country. One has been named in the records as Rodney Hickman, Support Worker, NSW Teen Challenge Inc., NSW Teen Challenge Support Group, 87 Macleay Street, Potts Point, (NSW 2011). In these fledging days of incorporation, and in the failure of Australian federation, the New South Wales work, and then the Victorian work, and then the South Australian, operated separately and the ignorance abounded of who did what.

By 1975 Peter Lane was the Rehabilitation Director, located at 103 Simpsons Road, Bardon (QLD 4065). In the same year, Gary Swenson, Lorna Swenson, Rita Ringma, worked as Manager and Co-Manager, Counsellor, at the Teen Challenge Inc. Girls Home, Red Hill. A few years later saw the acquisition of the Rathdowney Farm as a rural facility, and the Teen Challenge Drug Referral Centre was set-up at 9 Hall Street, Paddington (QLD 4064). By 1980 the Rehabilitation Appeal was launched.

A previous essay has picked up on the role of Koinonia Drug Rehabilitation Centre, Teen Challenge Inc., as a story of short-lived hope for bigger things to come. It had to wait until the new century, but the early players were Neil Paulsen, Sue Paulsen, Roy Calic, Lyn Calic, Margaret Robertson, John Moutou, Mike Bellas, Mike Power, Chris Cummings, Neville Buch, and host of names not listed here.

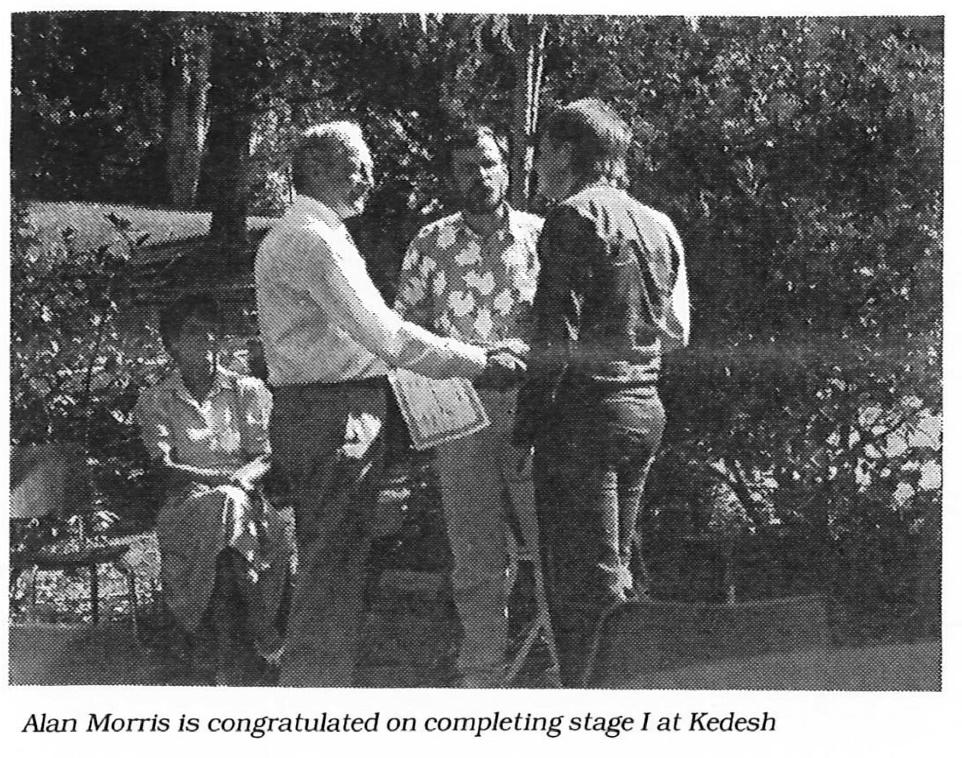

The official opening of the Kedesh Male Rehabilitation Centre was to be the 3 May 1987 but the guest of honour, Reg Yake, died before he got to Brisbane. Instead, the Re-Dedication of the Kedesh Male Rehabilitation Centre went ahead on 15 December 1988, at 254 Flinders Parade, Sandgate (QLD 4017). Rick Raetz was the Co-ordinator. Little remains on records for the Maleny Rehabilitation Farm and the Sunshine Coast Rehabilitation Centre.

Figure 9. Graduation of Kedesh Male Rehabilitation Centre, 1987. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Education (Prevention)

The TC workers were progressivists. The programs were not only about picking up the damaged after the fact. Teen Challenge Inc. was about the education for prevention; preventing young people falling into a drug habit.

In 1972 the program was a matter of a small visitation with the coordination of a few high school teachers, such as the Cooroy State High School I.S.C.F. Outreach. Larger High School Visitation Teams were then formed, such as the Teen Challenge Chinchilla High School Visit. This included John Healey (Director), Jeff Ganter (Graduate), Josephine Horrochs (Team Assistant), and Chris Adams (Director of Drug Awareness).

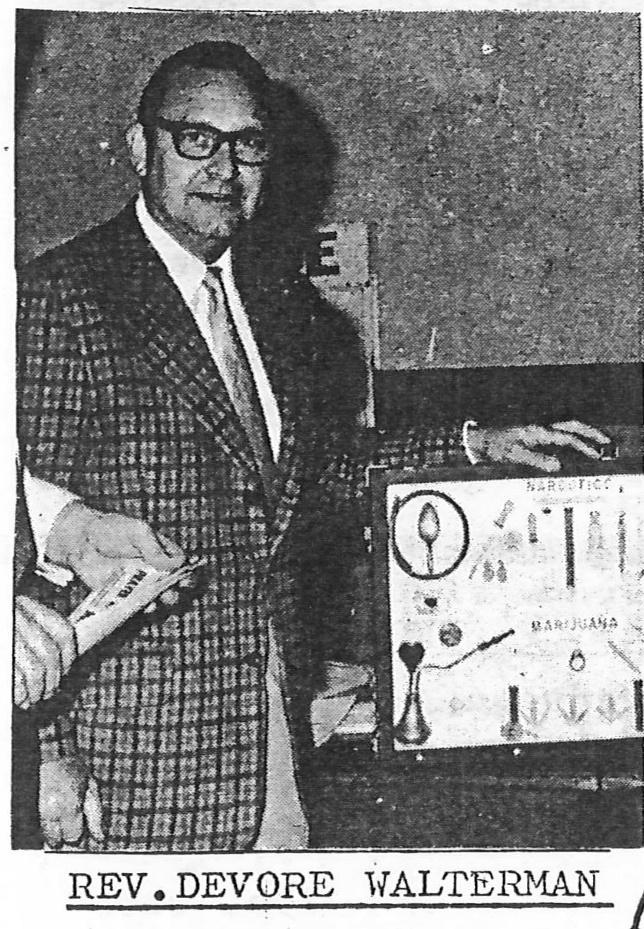

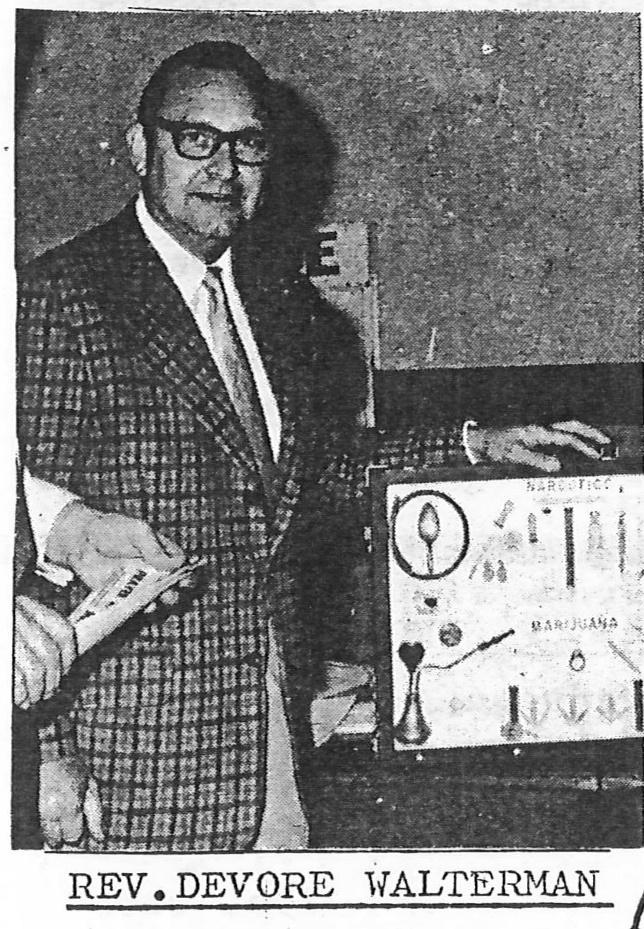

Figure 10. The De Vore Walterman event. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The year 1973 gave a lift with the visit of De Vore Walterman, Executive Director, US National Council for Prevention of Drug Abuse, and speaking at Brisbane Drug Awareness Meetings. The messaging went something like Teen Challenge Inc. is ‘the Jesus Movement’ to the dangerous ‘The Drug Sub-Culture.’ The problems of the culture are deeper than addiction and answers lies in transforming young persons into a redeeming culture (Christian). The messaging appears conventional for the American thinking, but the challenge underlying the messaging was the alignment with contested United States drug policies. Between blanket prohibition and blanket permissiveness were a host of realities of which the likes of De Vore Walterman struggled to understand. In the Australian setting Charles Ringma was more in tune with the way drug policies were double-edged and contradictory.

Education: Teen Challenge Training Institute

Both for drug rehabilitation and education, heart of the organisational operation was the Youth Workers Training Seminar, which became the National Teen Challenge Diploma Training Course (one year long), operated as the Teen Challenge Training Institute (TCTI).

In 1972 John Healey trained for two and half months at the San Francisco Teen Challenge Center. This became the basis for the Brisbane training program with Australian modifications. It appears that it took a few years for the training to be formalised as a full seminar program. In the week of 14-18 January 1974 Healey organised the Evangelism, Counselling and Youth Problems Seminar at the West End Methodist Church, Vulture Street, West End, (QLD 4101). The other trainers included in the seminar program were Charles Ringma, Athol Gill, Chris Adams, John Carrol, Jim Christian, Greg Job, Bob Pearson, and Gloster Udy from Sydney.

By 1978 Charles Ringma began his part-time clinical teaching with the University of Queensland Medical School, on social medicine and legal and illegal drug abuse. The year 1981 saw the chaplain Brendan Scarce became the National Director, the role being in actuality the National Teen Challenge Diploma Training Course (one year long). Charles functioned in the first year of the course as the National Director, and the course eventually moved to include interstate Teen Challenge organisations and to which the social worker Brendan Scarce had prime responsibility.

Education: Queensland Pedagogies (and research).

A few analytical observations can be summarised as the research pedagogies. In 1971 Charles Ringma is the LifeLine researcher to find the most appropriate service, what is coined AOD – Alcohol and Other Drugs. The binary between ‘alcohol’ and ‘other drugs’ expresses the confusion in the social model with the vague category of ‘Other’. In that mix is other pedagogies. There is the educational mix an expression of social fears about the dark world and also a fascination with the underworld drama, common to the thinking in American liberal art colleges of the era. It is picked up in the language of De Vore Walterman, and of Dave Wilkerson’s Cross and Switchblade.

The Teen Challenge education required more, and it was delivered in the connections to the leading Queensland Christian educators, such as Rev. Dr. Lew Born, the Director for the Methodist Department of Christian Education. And the few academics associated with Teen Challenge added another layer – academics such as the criminologist Dr Paul Wilson, who in those days was Acting Head of Department, Anthropology and Sociology, University of Queensland. Charles continued his role as a researcher, and by 1976 he has begun the B.A. degree part-time at The University of Queensland majoring in Sociology and Studies in Religion.

Figure 11. John Healey leads the Teen Challenge Chapel Service, circa 1973. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

ACTIVITIES

The buzzword for pedagogies in the last half century has been praxis, the running together of theory and action, activities in the current thinking. What did this mean for Teen Challenge Inc.? The rationale behind the facilities which the organisation ran provided theoretically based action, or put another way, or action shaped as theory.

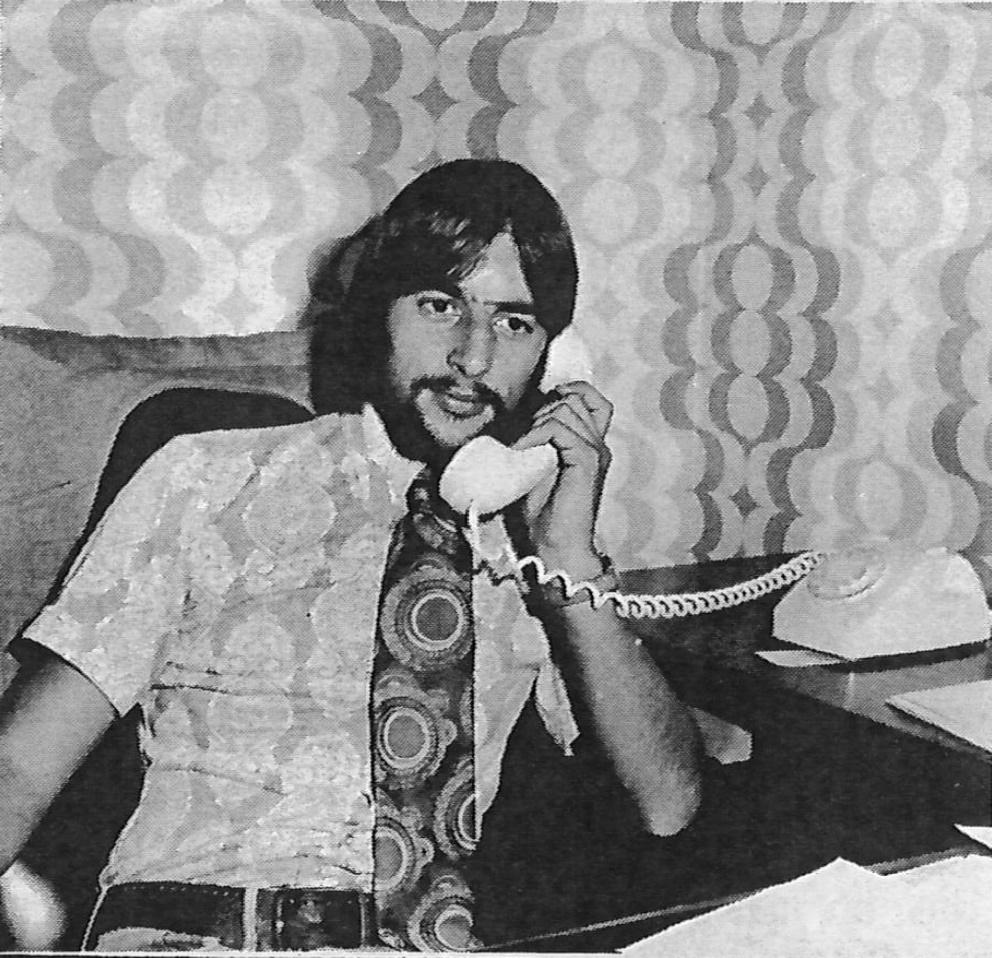

Phone Communications ministries

The shift in communication theories were coming from different directions but they overlapped in the action. Indeed, communication action was another buzz phrase. The global names which buzzed in the local scene in the decade of the 1970s and 1980s were theorists headed by John Dewey, Jurgen Habermas, Marshall McLuhan, Theodor Adorno, Antonio Gramsci, and George Herbert Mead. Many more names could be added, but these six philosophers and sociologists were immediately recognisable. The names stretched across a large part of the mid-twentieth century. McLuhan coined the expression, ‘the medium is the message’. The idea that that a communication medium itself, not the messages it carries, is the revealing focus of study. It is beyond the full explanation here but goes to the beginning of Teen Challenge Inc. in the activities of the phone communications ministries, which started as a connection between the first coffee shop, ‘His Place’, and LifeLine. The Phone medium is the Interactional Model of communication. It is bidirectional, where two persons send and receive messages in (hopefully) a cooperative manner as they continuously encode and decode information. Compare that earlier medium to the social media today. Communication on these new mediums is chaotic involving many more than two persons.

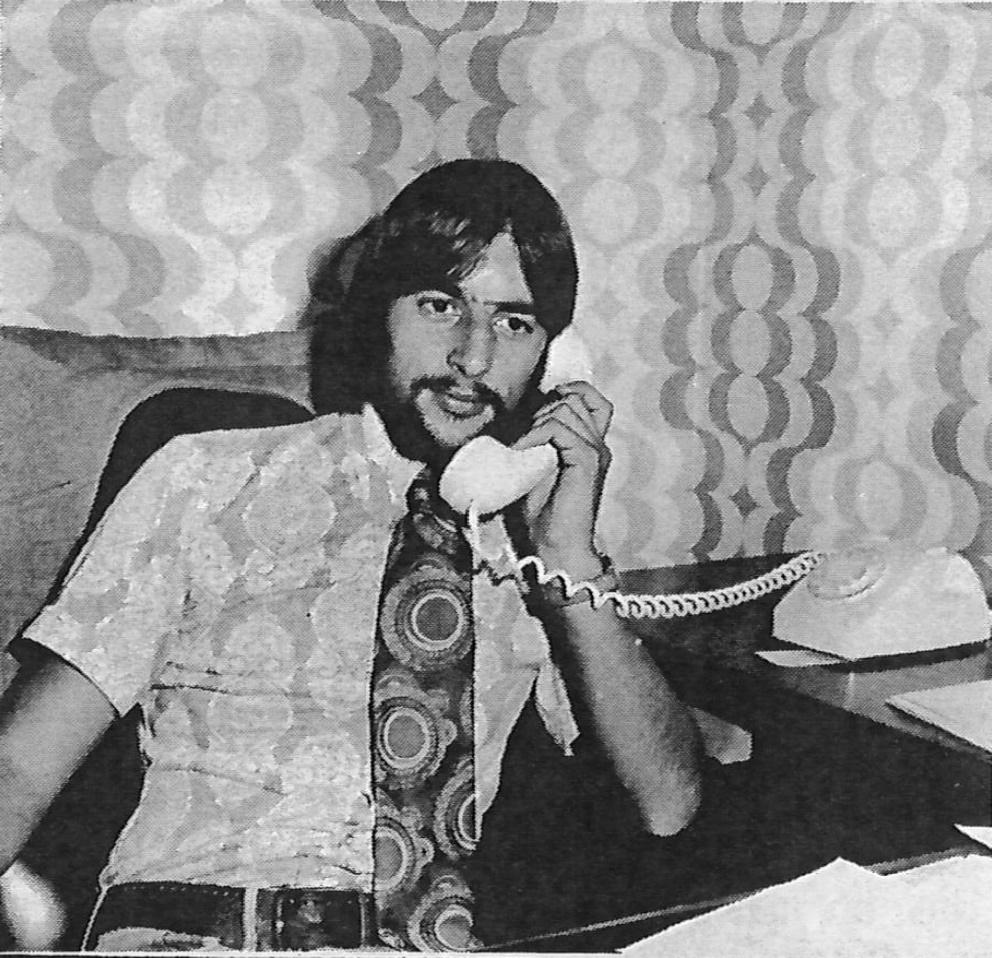

Figure 12. Chris Adams ‘on the phone.’ Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Back in 1972, soon the ministry became known as ‘Teen Dial’ with an office outfit at 19 Eagle Terrace, Brisbane City (QLD 4000). How long it stayed in the expensive area of city properties is uncertain. Harvey Pollock became the LifeLine Coordinator with Teen Challenge, based at the Teen Challenge Inc. Head Office, Enoggera Road, Red Hill (QLD 4059). Oversight came from Charles Noller, as the Director, Counselling, LifeLine, and the TC Council of Reference member.

Respite Ministry (Farms)

Very little information among the records have been kept on the Teen Challenge respite ministry, closely associated with the rehabilitation program. The activities have to do with the farms leased by Teen Challenge, the first being, in 1974, the NSW Teen Challenge Farm, in Connabarabran, (NSW 2357). Very little is also known of the Rathdowney farm. It appears that the urban rehabilitation centres were utilised for the main part of the program. The farms provided respite spaces for both clients and staff members, leaving urban pressures behind, with some geographic distance.

Figure 13. Teen Challenge Rathdowney Homestead Retreat, circa 1974. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Primmer Lodge and Hebron House

More is known of the urban houses in Teen Challenge Inc.; however, the purpose of the essay is only to sketch the organisational history. More will said in the book, and feedback is welcomed.

The 1977 opening of Hebron House (emergency short-term accommodation) began a period of organisational renewal. Located at Milton Road, Toowong (QLD 4066), Mike Hobbs was the Director for Homeless Youth, Hebron House. Terri Hobbs was a Support Worker, as was Mark Cleaver, Helen Wallace, Tony Bennett, Gary Sivyer, David Smith, Paul Cummings, Steve Jeanerret, Mike Hobbs, Philip McLennan, Mike Power, Terri Hobbs, Liz Payne, Margaret Robertson, Janice Jordin, and host of names not listed here. Philip McLennan became the Director in 1980, and Mark Cleaver was the Children’s Services Co-ordinator for Hebron House. Other TC Workers also were Children’s Services Co-ordinators: Helen Wallace, Tony Bennett, Gary Sivyer, David Smith, Steve Jeanerret, and Paul Cummings. In 1984 Mike Power became the Director with Alec Spencer beginning his stellar rise in the organisation as a Hebron House worker. Spencer would become the Hebron House Director in 1987.

In 1978 the Minister for Welfare, John Herbert, officially opened Primmer Lodge (long-term support accommodation). This was a watershed moment in Teen Challenge Inc. A growth in TC volunteers formed around Primmer Lodge, at 18 Bellevue Parade, Taringa (QLD 4068). Among the volunteers recorded were Peter Allen, Brian Gibson, Liz Payne, Sue Peel, Ros Stark, Gary Uhlmann, Chris Cummings, and Peter Wilson. The Primmer Lodge workers included Lyn Meier, Helen Wallace, David Smith, Marylin Smith, and Jean Claude Boulenaz was the Manager.

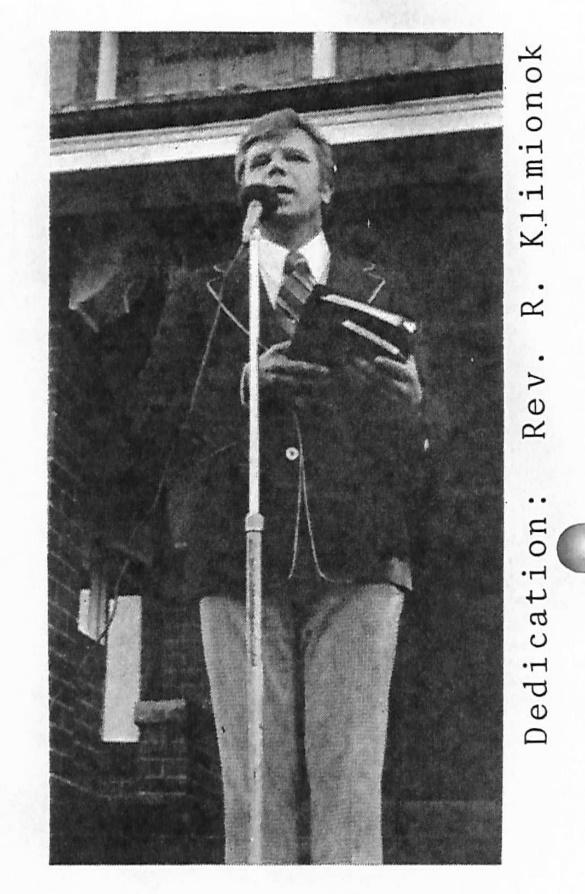

Figure 14. Pastor Reg Kliminonok, speaking at the Opening of Primmer Lodge, 13 May 1978. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The moment tended to overshadow the organisation work for the men’s and girls’ homes, in Paddington and Red Hill. Gary Swenson, as the Manager, of the Teen Challenge Girls Home, and Lorna Swenson, as a Co-Manager, is important to the story but little is known.

It is hoped that the set of online essays will provide more detailed information from comments offered up.

Youth Activity Centre

The front door to Teen Challenge Inc. was, for several decades, the Youth Activity Centre at Alfred Street, Fortitude Valley (QLD 4006). There were several TC directors, Tony Bennett and Wayne Porritt among them, and other workers who passed through the Centre, Alan Ruthford among the earliest in 1975, when Teen Challenge Activity Centre, actually began at the Focal Point Arcade, Wickham Street, Fortitude Valley (QLD 4006). Claire Fielding was a stalwart in the centre over the decades until the early 1990s.

Figure 15. The Offical Opening of Teen Challenge Activity Centre, 1982. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Prison Ministry

In the organisational background, out of the limelight, was the TC Prison ministry, based at the old Brisbane Goal (‘Boggo Road’), Annerley Road, Dutton Park (QLD 4102). The tireless workers in the ministry were Doug Boyle, Norm McIntyre, Margaret Robertson, Shirley Allan, and Claire Fielding.

Rallies and Concerts

There was an informal side to the Teen Challenge Inc. which involved rally and concert promotion in the office environment. Tickets were sold, sometimes as an event of promoting the Teen Challenge mission, such as the Nick Cruz Rally in 1975, or as a fundraising event as in the 1976 Andrae in Concert. In both of these cases the venue was the Festival Hall, Alice Street, Brisbane City (QLD 4001). These were events that had a megachurch feel in the era before the Brisbane megachurches. The Christian religion was becoming the art of the showman in the ‘mega’ ways – mega Christian rock bands, loud and in your face, and faith was a ticket to entertainment. It was not that there was not something existentially genuine in the experience for the youth of the day. The local Brisbane band, ‘His’, delivering the Pink Floyd version of Jesus the anarchist – we were not going to be another brick in the wall. The Teen Challenge youth of the last quarter of the twentieth century became the leaders of the local Church. What has escaped the attention of the institutional Church, in its talk of orthodoxy, is how heretical the history is.

Concluding Remarks

The working for the history during 2022 will need assistance from past in present voices. Much more is to be done on the welfare agency, Good News Centre working with alcoholics in South Brisbane, and the office volunteers, such as Joyce Krassenburg, who is only a name in the records.

New Governance and Administration invested in Workers.

With small organisations, it very common that governance and administration is in the hands of the ‘ordinary’ or ‘labouring’ worker. There are partial stories collected.

Even as Teen Challenge Inc. expanded, the habit of a worker-leader continued. The organisation was among those that did not abide the rigid distinction of modern capitalism between those who laboured and those who managed labour. In the postmodern world the distinction has become an absurdity. Nevertheless, for any organisation it is almost impossible to completely get rid of a hierarchical outlook, given enough tasks and the time to do it in.

In thinking how much more of the story has to be told, consider a snapshot picture sometime in 1975 at the Teen Challenge Inc. Head Office, Enoggera Road, Red Hill (QLD 4059), or the relocation to Head Office, (Woolworths Shopping Centre) 107 Latrobe Terrace, Paddington (QLD 4064).

There is the leadership of Geoff Dean, a worker from the Catholic Tradition, who unknowns to him, would create a scholarly career from the work in the decades ahead. In that office environment were regular visitors, Hans Booy, the TC Campus worker; Ian Thomson, TC Worker, Architect and Moore College graduate; and Glenda Reinhardt, Rehabilitation Worker. There is Harvey Pollock, the Business Deputation Worker, chatting away. Peter Jones and Roslyn Stark are barely listening as office workers. Forms and other records have to be completed.

Please help, much more is to be said.

by Neville Buch | Jul 27, 2023 | Article, Concepts in Educationalist Thought Series, Concepts in Public History for Marketplace Dialogue, Concepts in Religious Thought Series, Intellectual History

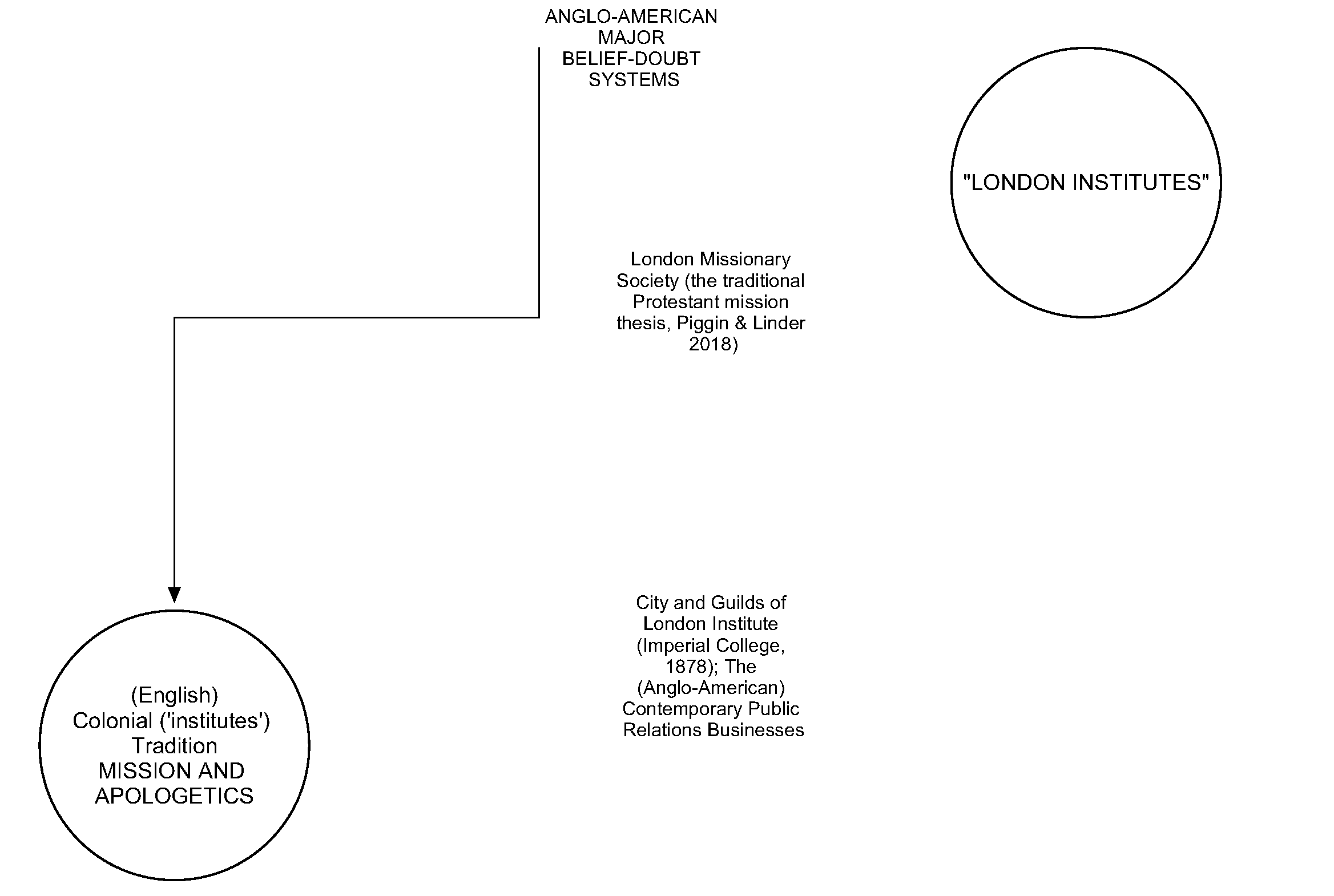

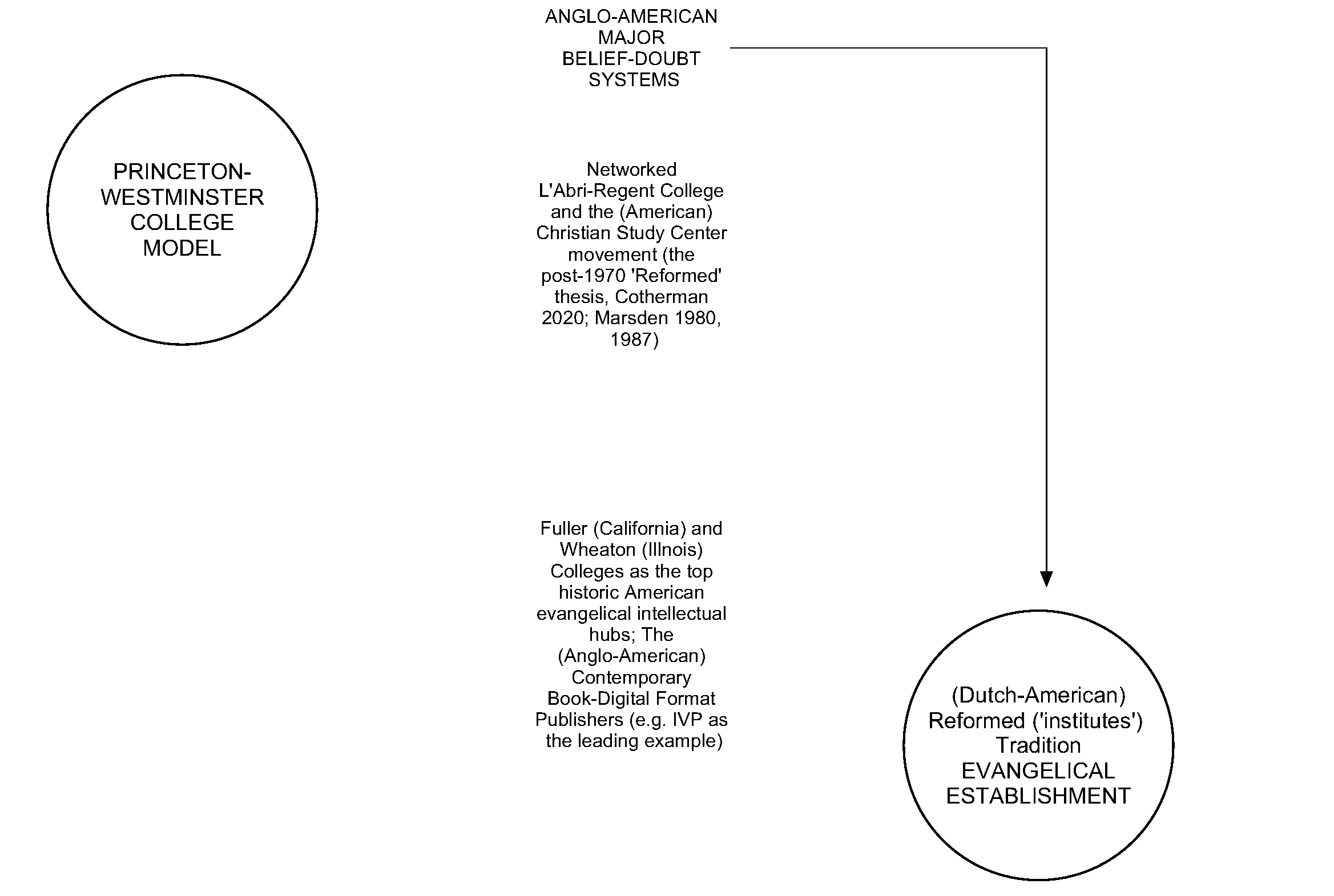

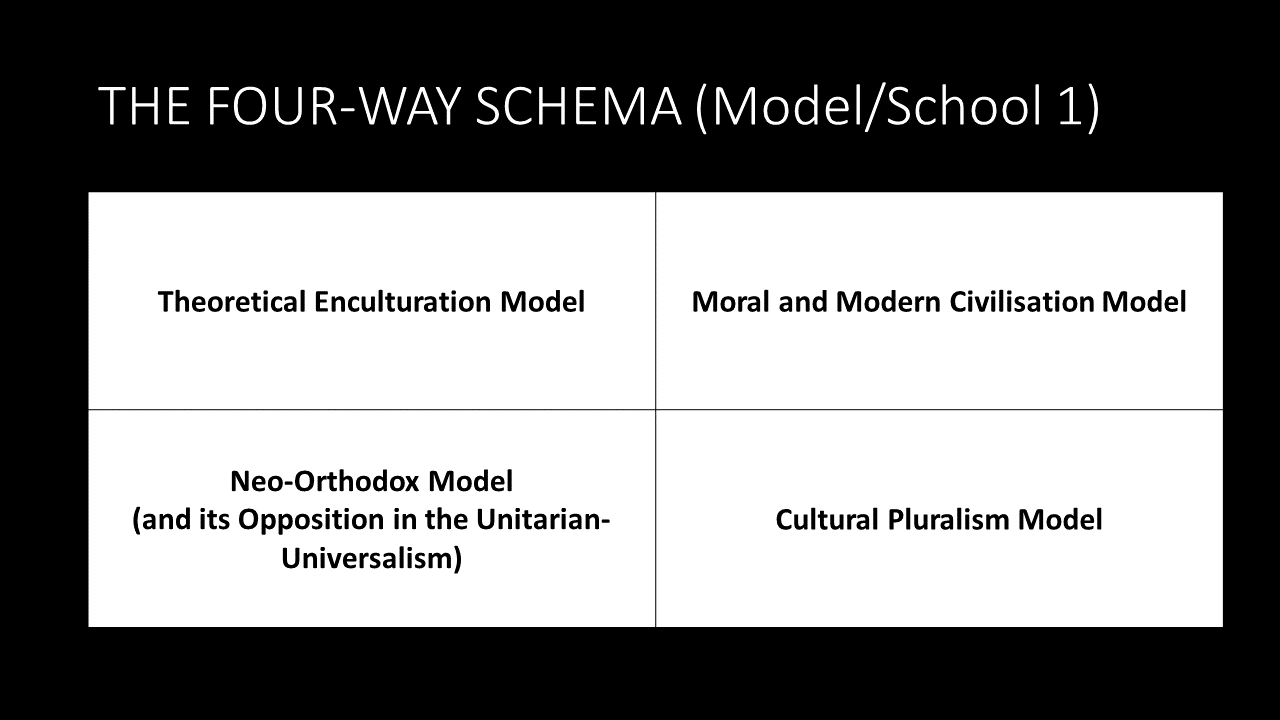

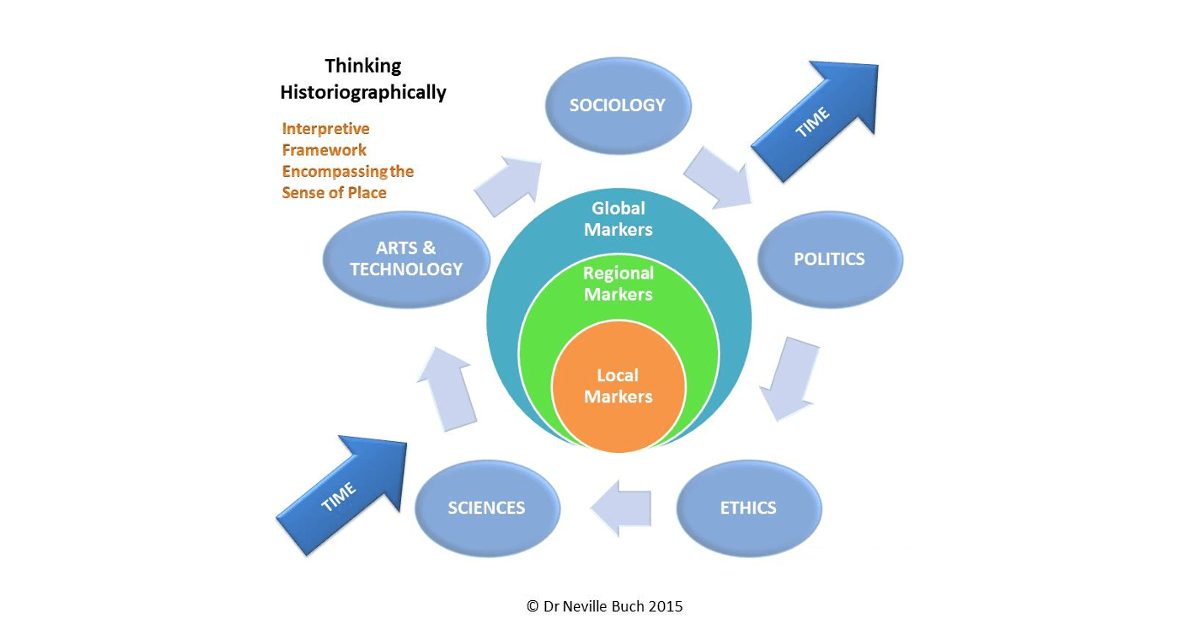

This is a research note to preserve copyright and notice to this new and substantive thesis of the Anglo-American major belief-doubt systems, since the seventeenth century, which at the end of that century expanded, and transformed, the power of the English monarchy to a new entity known as the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. The constitutional and national development coincided with the securing of the fledging English colonialism in North America, with entry, in the next century (18th) into the waters and landmass of the Asia-Indian-Pacific spheres. The concept of colonialism is not limited nor unique to the English-speaking worlds. However, in both threatening and beneficial ways, it produced Anglo-American belief systems, and both for the powerful colonisers and the disempowered colonised.

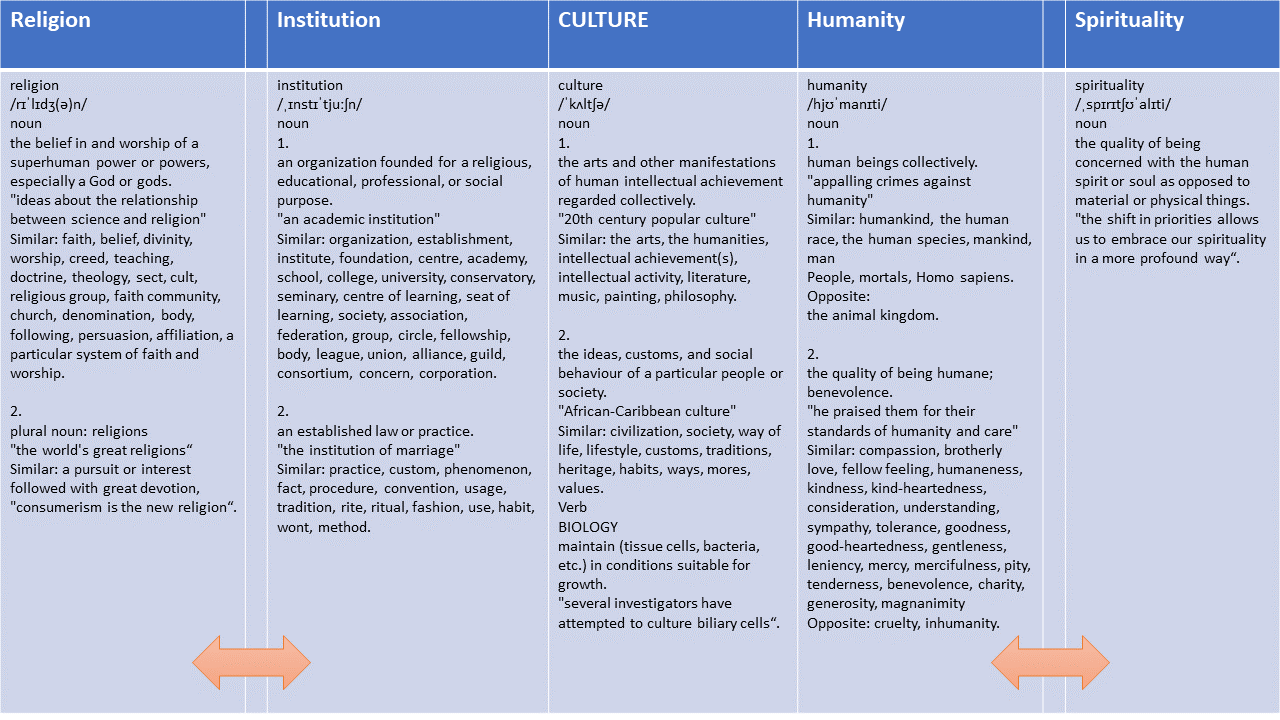

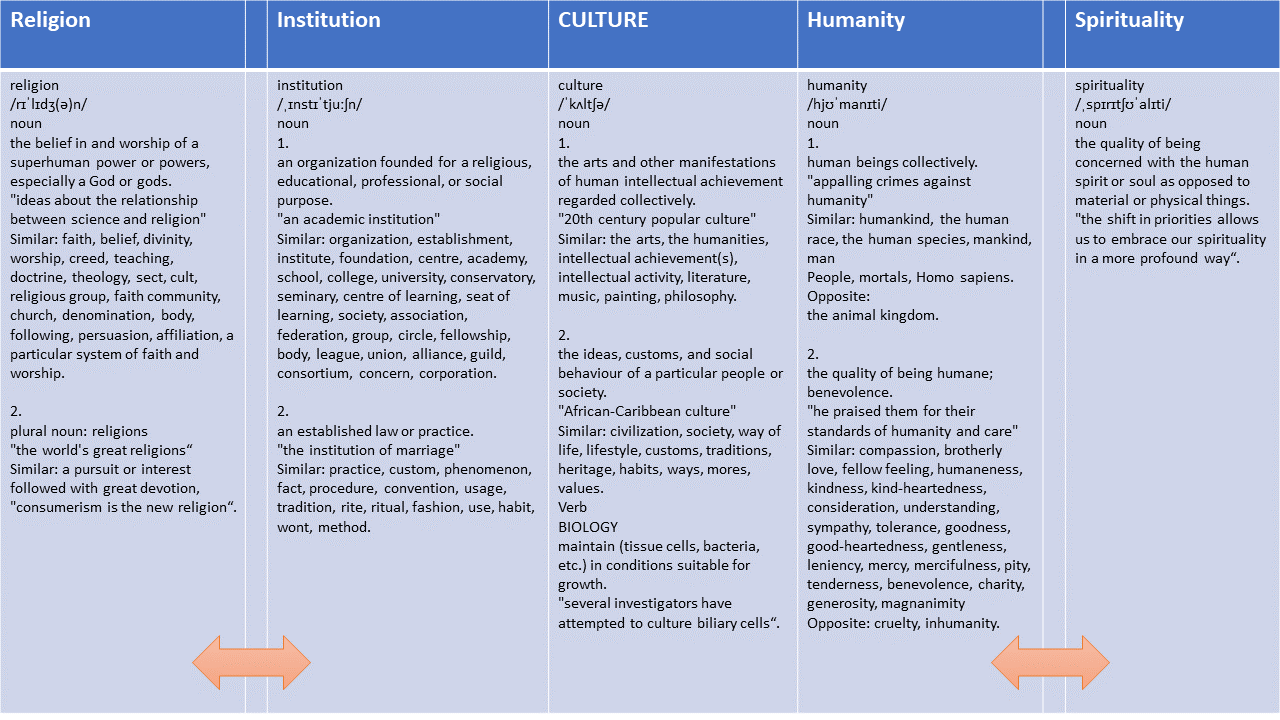

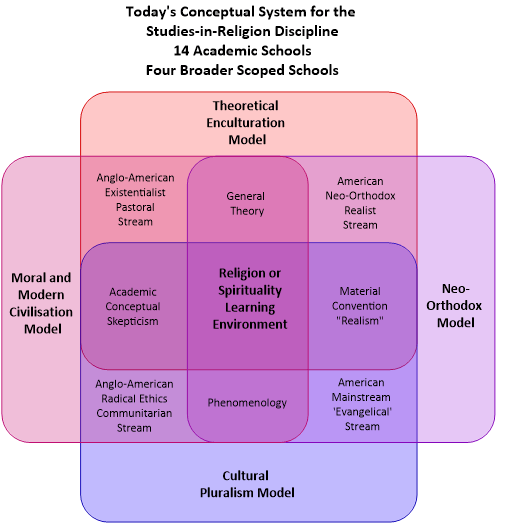

These belief systems, which includes its necessary skepticism (doubt), have usually been 1) called ‘ideology’, and 2) boxed as categories of ‘religion’ and ‘secularity’. Both these outlooks are problematics and are based on gross intellectual misunderstanding. First, ‘ideology’ is commonly used as a swearword to dismiss systems thought: out-of-hand, as (to be frank) a ‘blood-minded’ and ignorant defence mechanism. So, to be clear, references to ‘ideology’ and ‘ideological’ are used here merely as references to systems thought, either for good or bad. Secondly, the studies-in-religion field, more than half century, has clearly demonstrated that the hard categorisation between references to ‘religion’ and ‘secularity’ are false. Those who continue in that ‘categorical mistake’ (Gilbert Ryle, The Concept of Mind, 1949) are usually culture-history warriors.

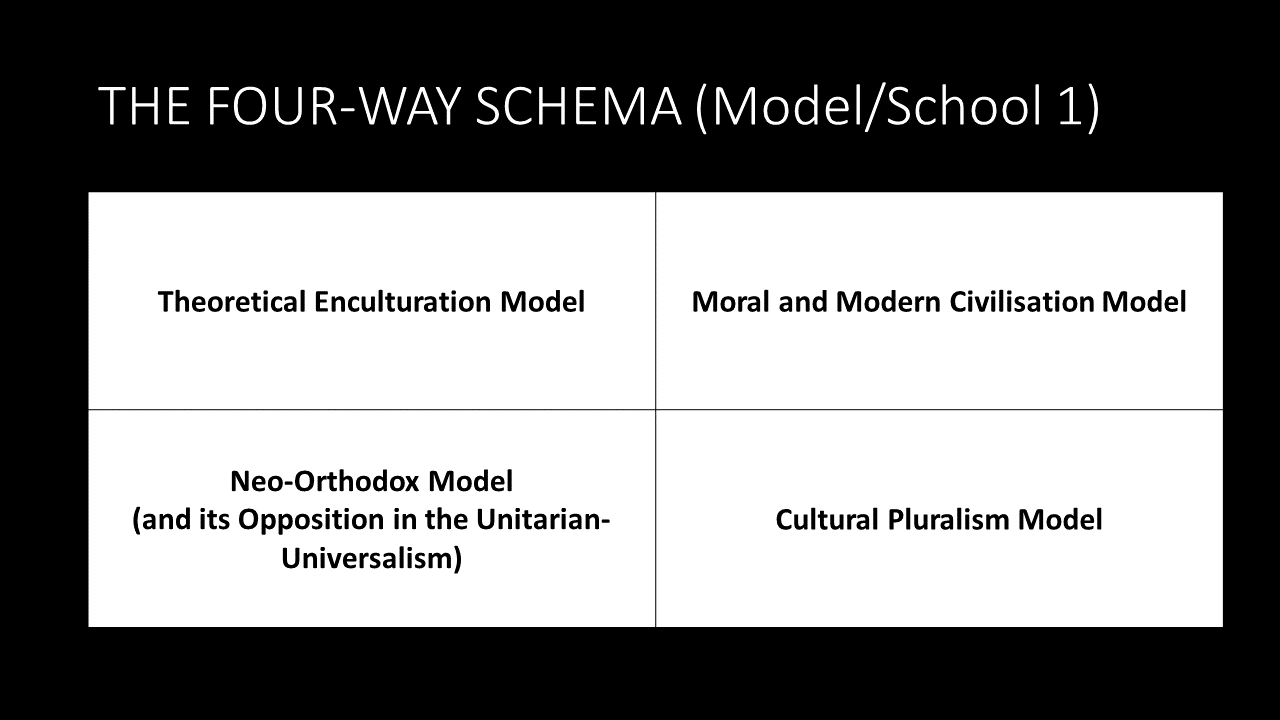

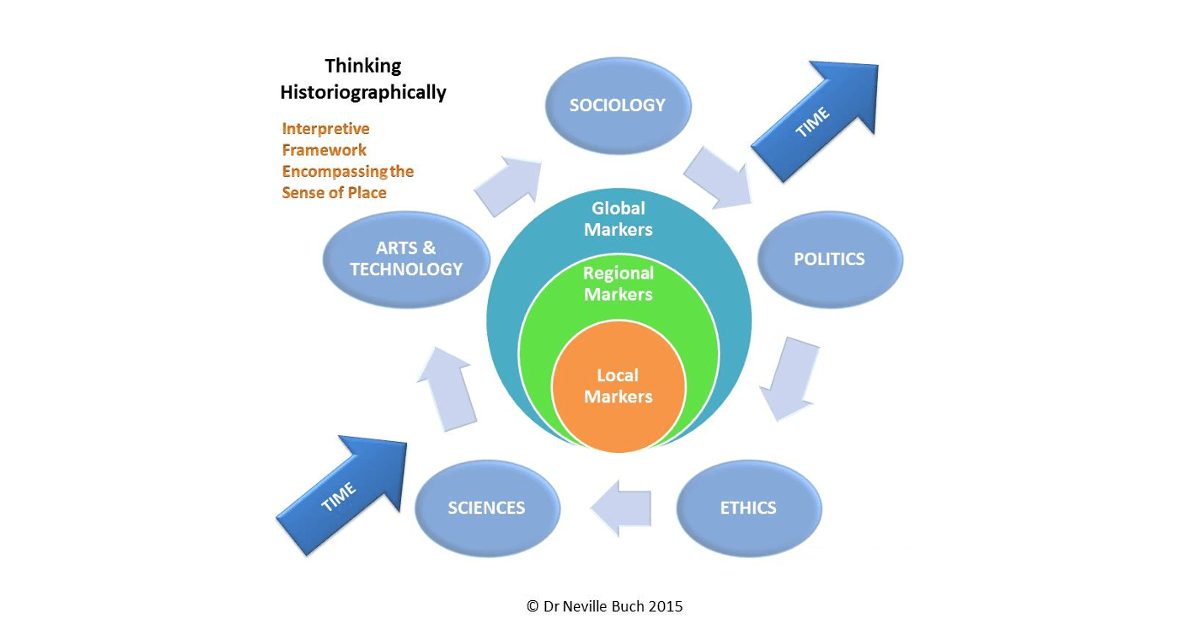

The structure of the research to 1) identify a basic worldview, 2) describe a model of that worldview which usually ties the evolutionary thread to a global university school or college or networked institutes. From those two steps is a selection of one key example in 3) the historic Evangelical World and one in 4) the (‘secular’) Corporate World, usually in a dual sense of a singular institute or school of thought and an industry or corporate grouping. In this way, a web of belief can be both described and explained.

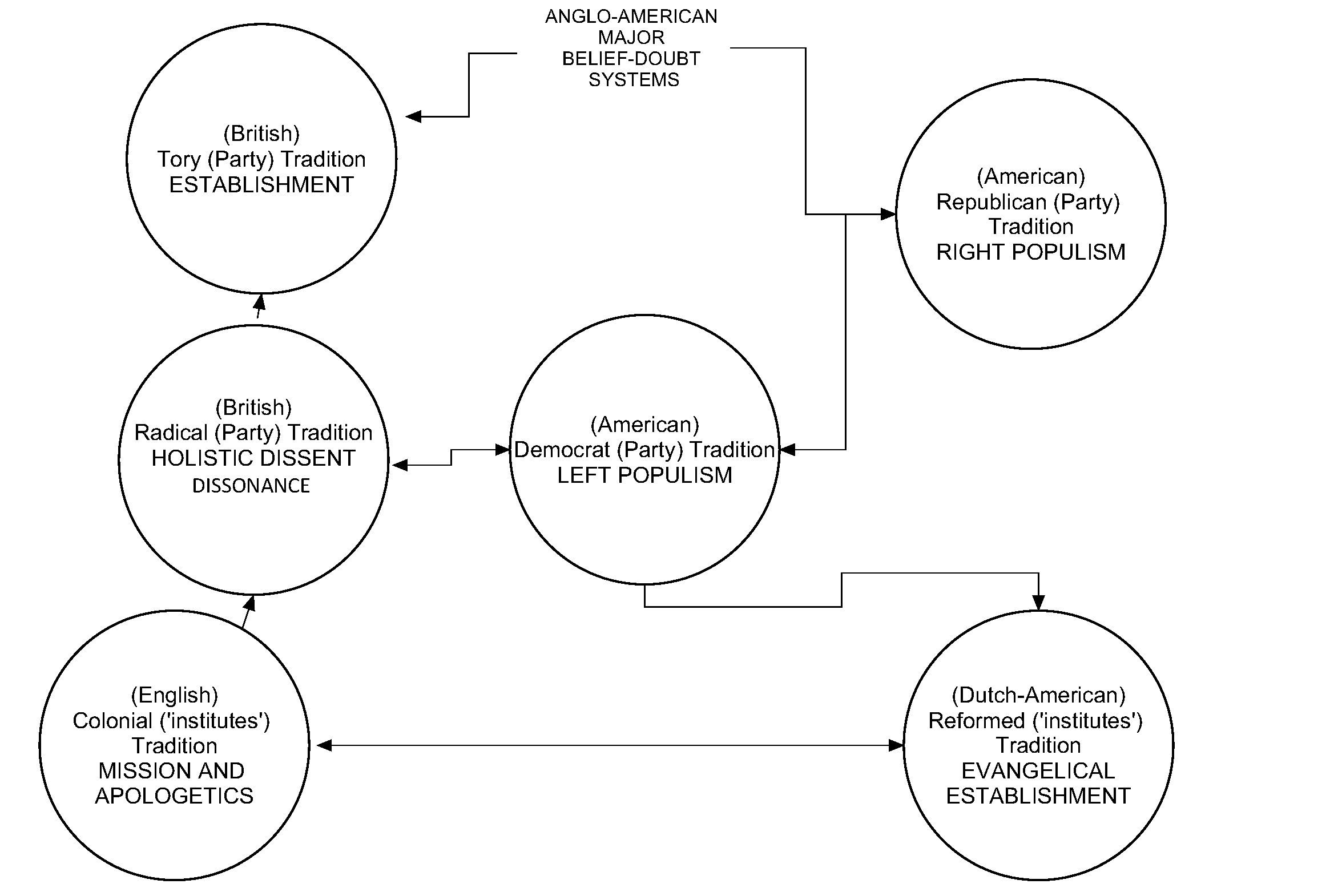

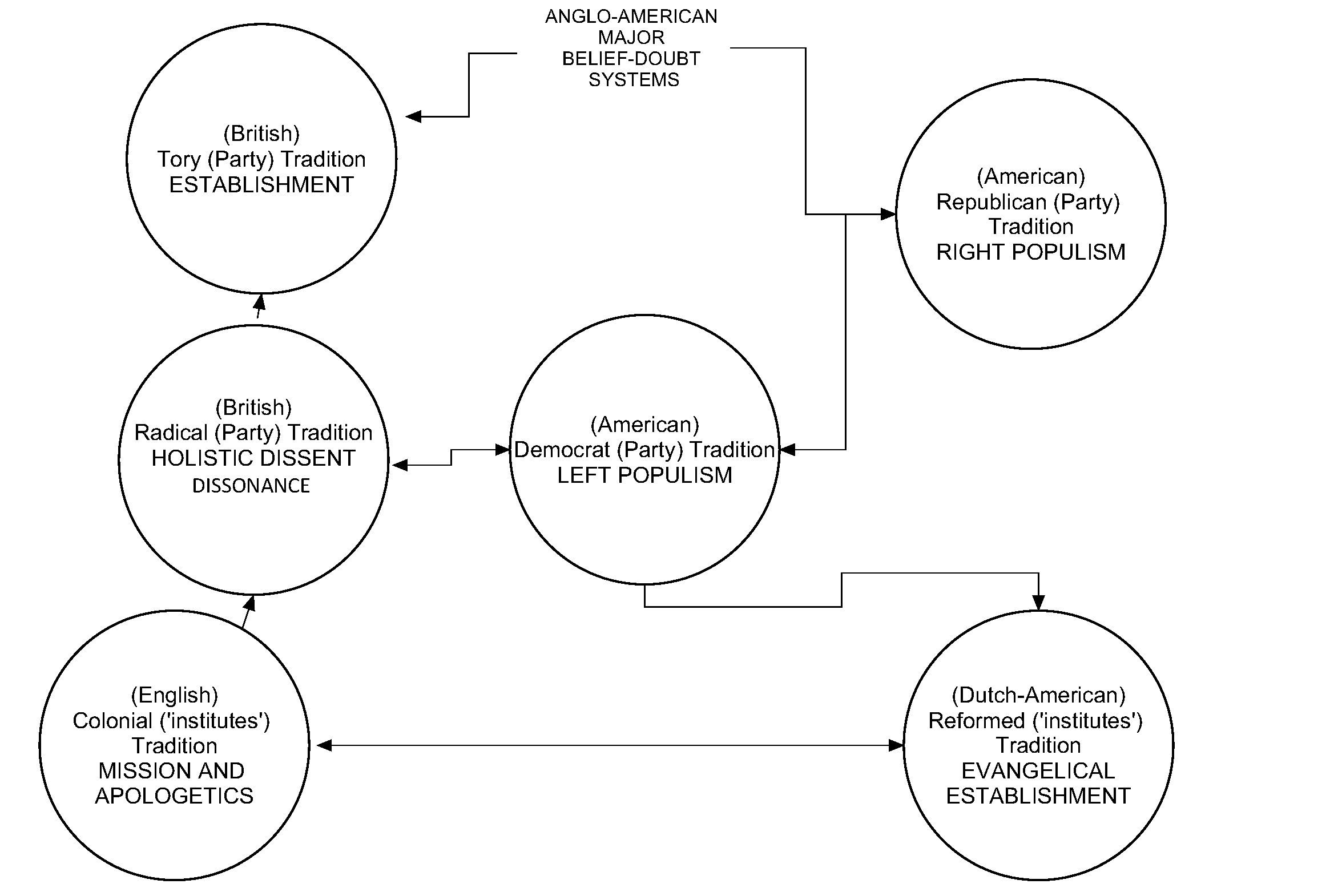

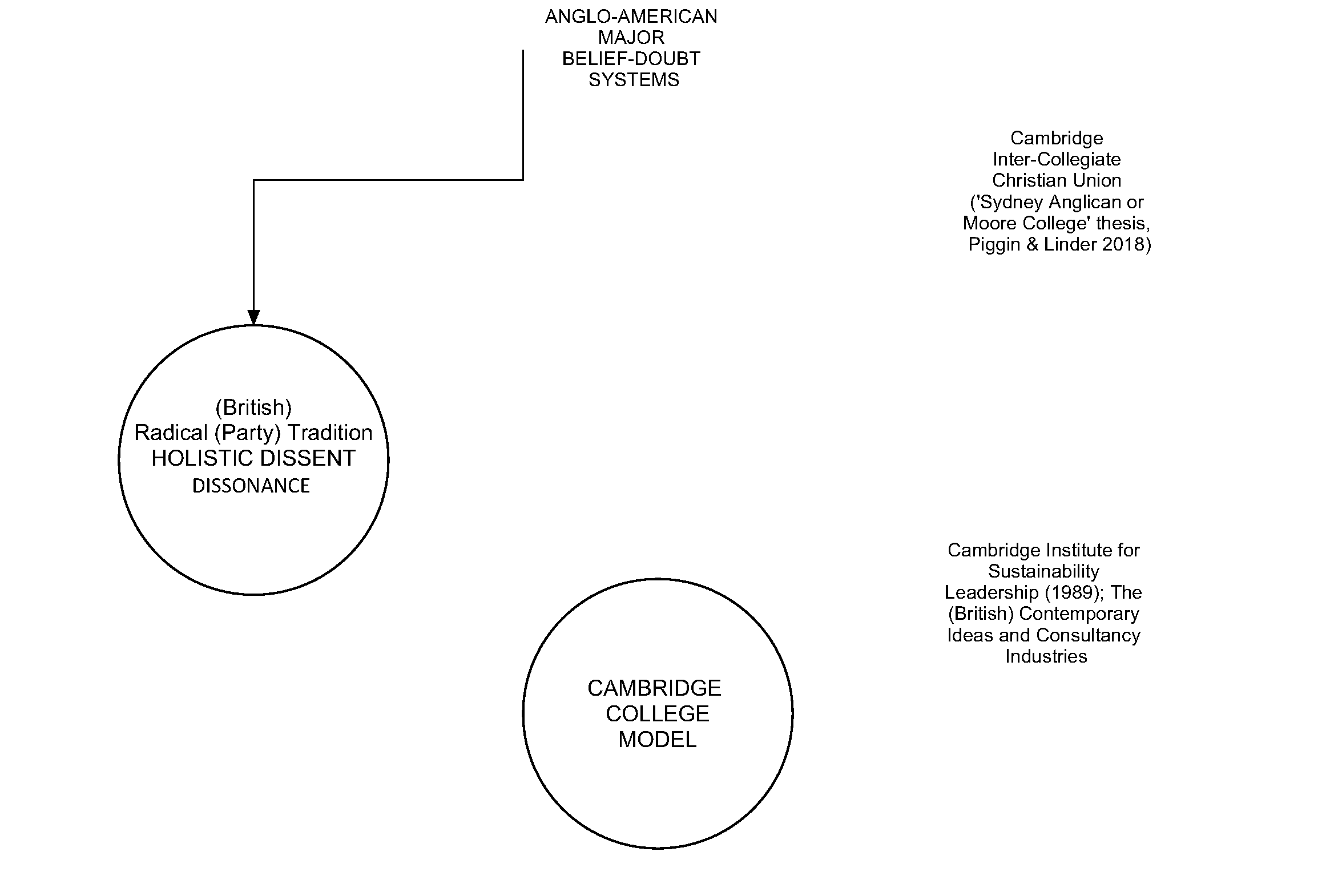

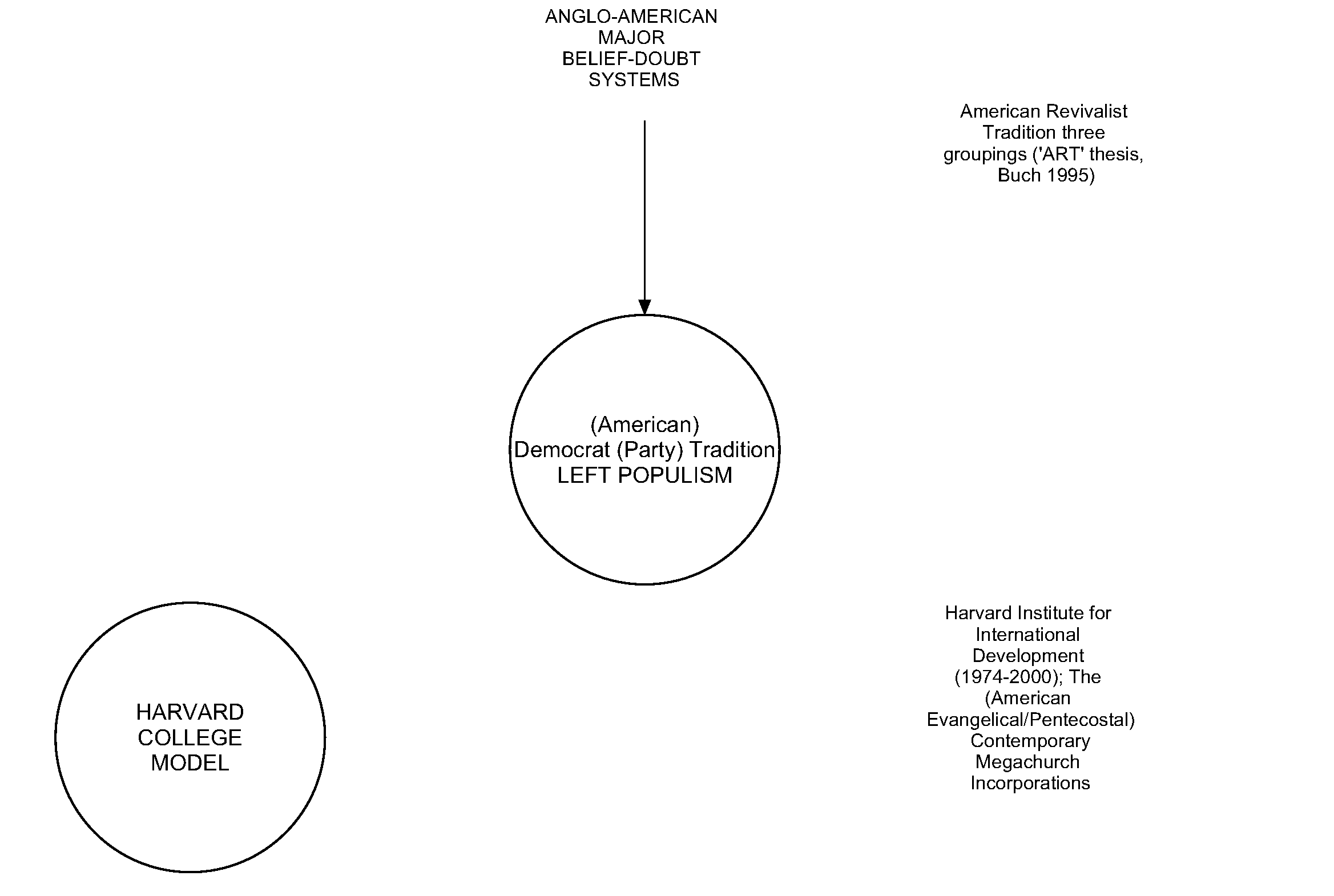

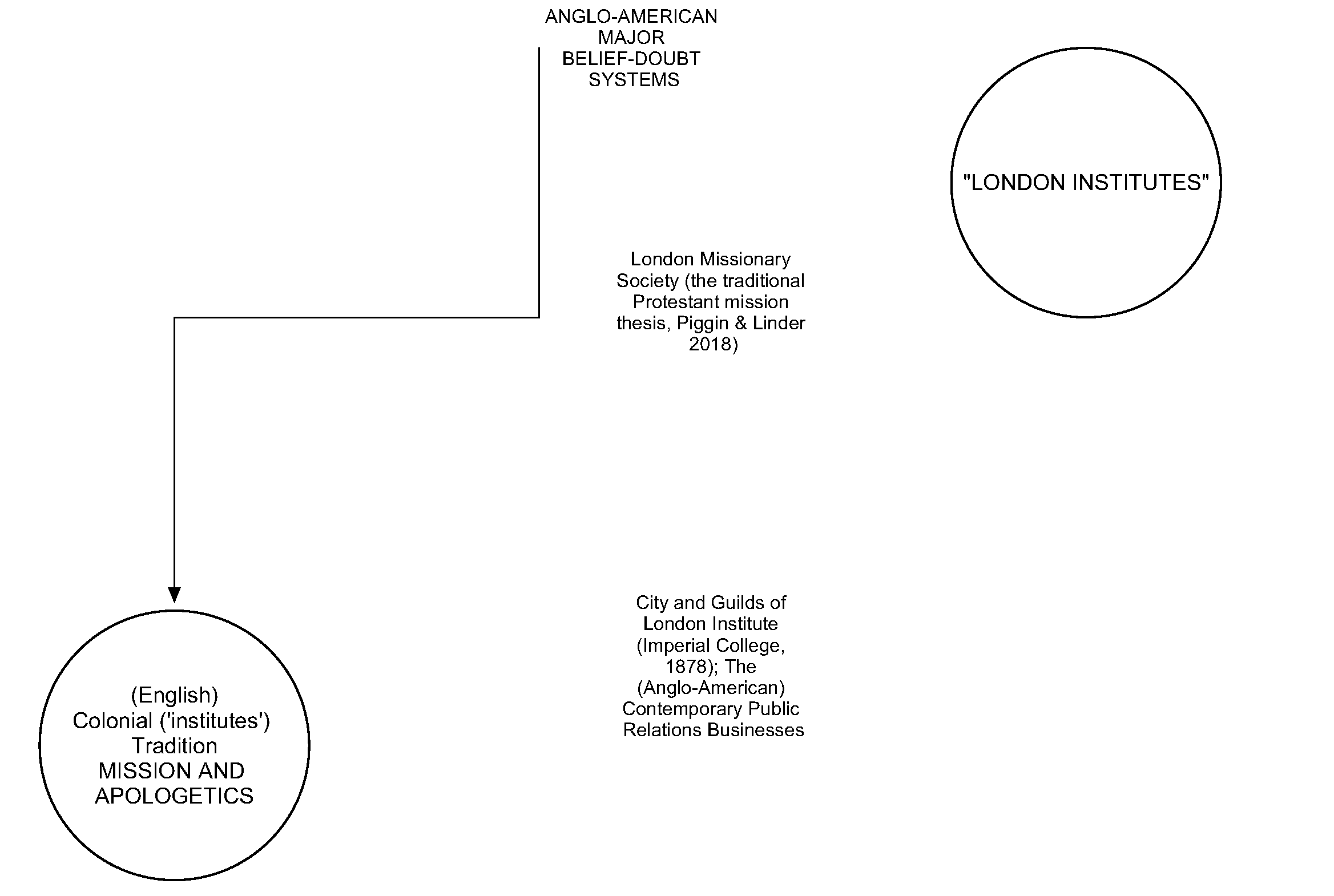

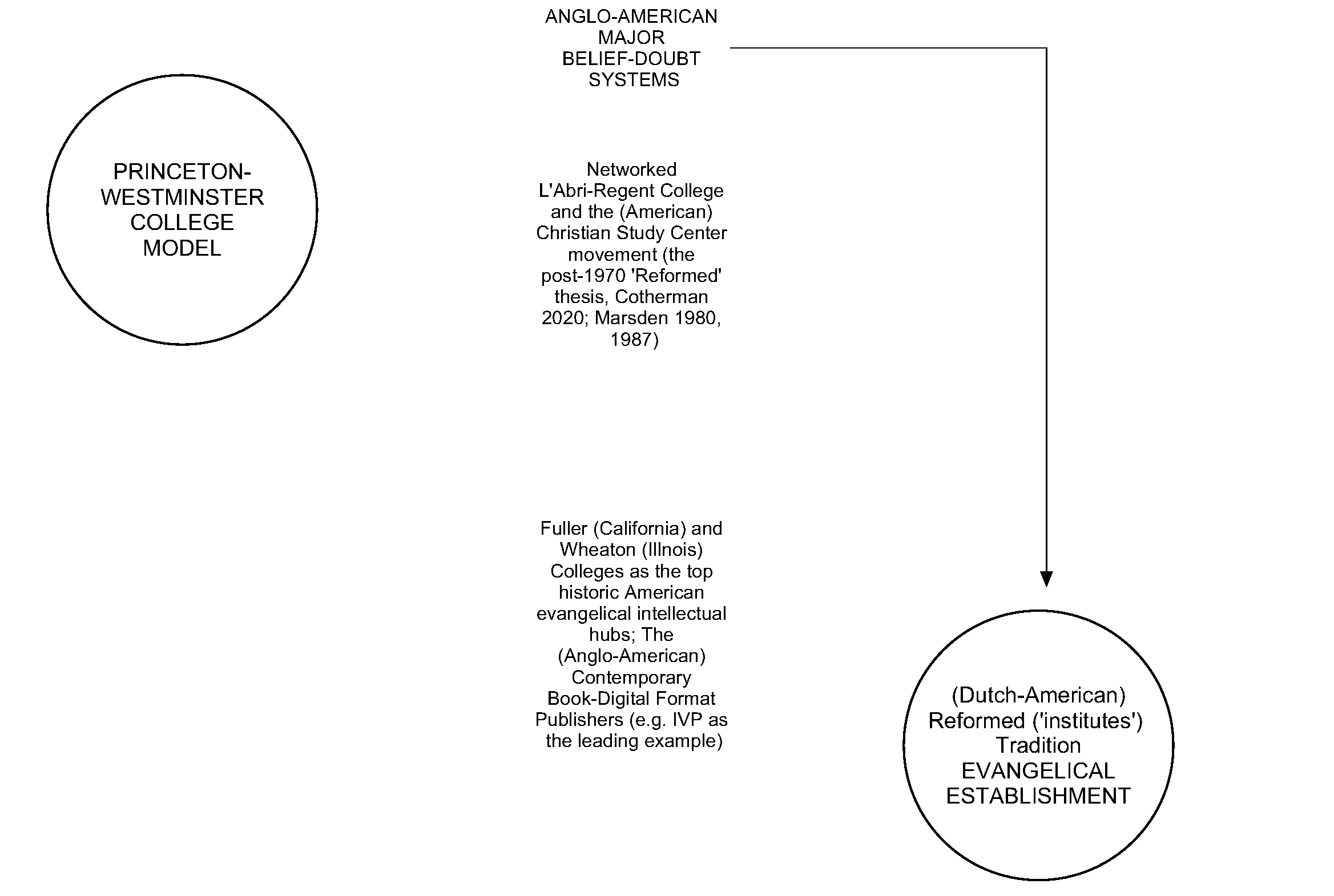

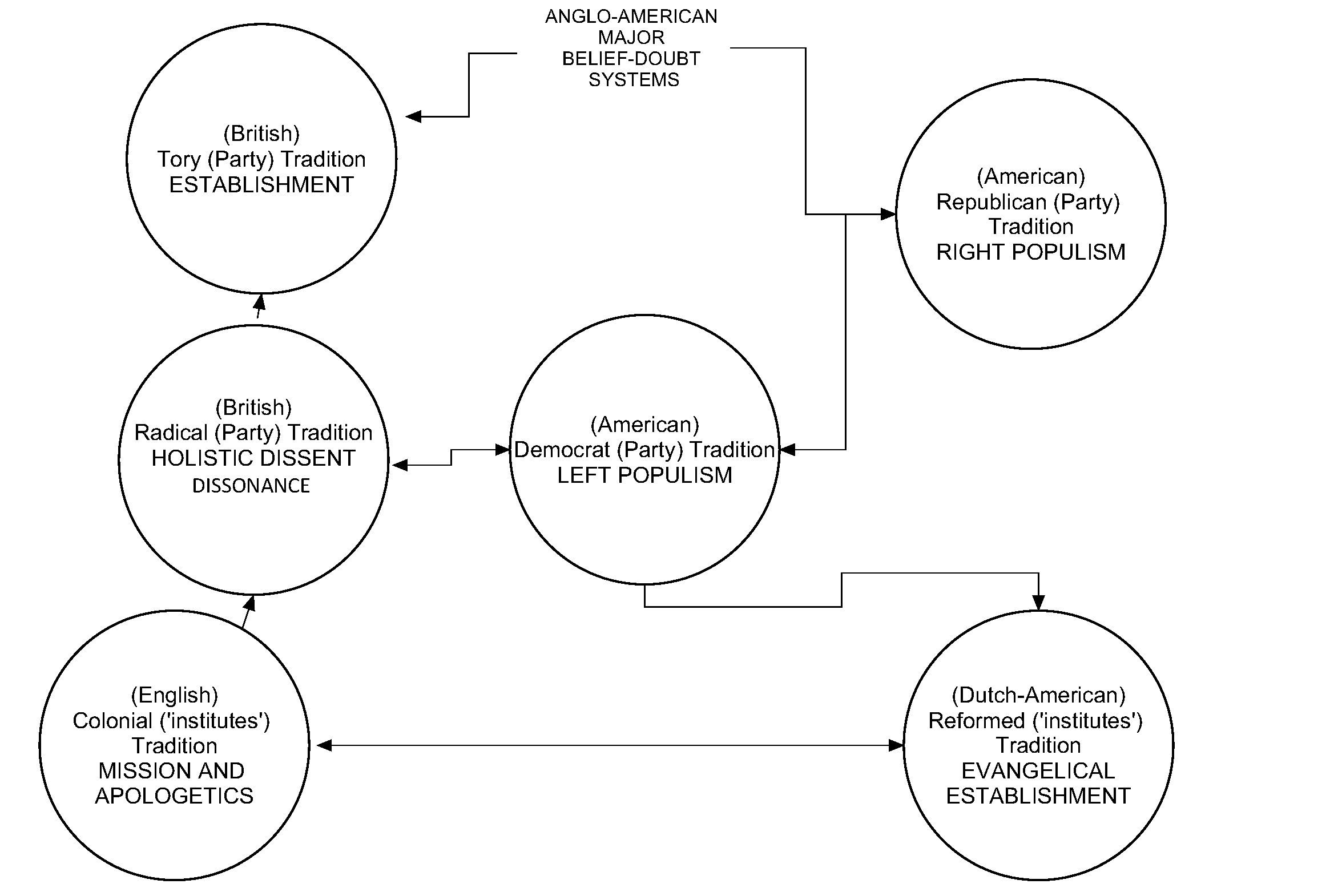

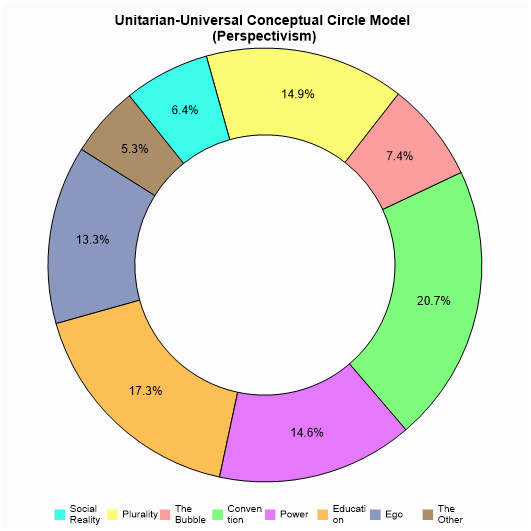

There are six basic socio-political worldviews. The descriptors identify a cultural reference, the usual ‘socio-political’ name, its usual status as either a political party or a social institute, describing the worldview as a tradition, and the usual tag as a common language by-word (in that order of the descriptive phrase):

- The (British) Tory (Party) ESTABLISHMENT

- The (American) Republican (Party) Tradition RIGHT POPULISM

- The (British) Radical (Party) Tradition HOLISTIC DISSENT Dissonance

- The (American) Democrat (Party) Tradition LEFT POPULISM

- The (English) Colonial (‘institutes’) Tradition MISSION AND APOLOGETICS

- The (Dutch-American) Reformed (‘institutes’) Tradition EVANGELICAL ESTABLISHMENT

- (British) Tory (Party) Tradition. ESTABLISHMENT.

The conservative tradition in the English-speaking world is best expressed by the ‘British Tory Party’: a descriptor for organisations such as the Conservative Party UK or the Conservative Party of Canada. Political organisations do not align perfectly with ideology, so Toryism is like any other social science model, a genealogical method (as in philosophical term of Nietzsche and Foucault), and, as Bernard William describes it, an origin-type fiction, paralleling the concept of myth, which broadly structures out the non-fiction truth (truthfulness propositions); thus, having accuracy but not the logical accuracy of mathematical truth (Truth and Truthfulness: An Essay in Genealogy, 2002). “The Conservative Mind” (Russell Kirk, 1953) appears to continually to trip-over with this misunderstanding of social science, in its rejection of the thought propositions within the outlook of modernity; ironically, the modernist propositions of hard scientific humanism (in the mid-century) led to a neo-conservative outlook to reject the Nietzschean genealogical method since mythology could not be taken as accurate scientifically. This is done in employing the fallacy of cherry-picking details and failing to understand the mythological or constructivist’s point; or to employ another metaphor, chopping down one tree (or even a few) and think that the concept of the forest has been destroyed; or extending the metaphor: being deaf to the forest in chopping down the tree. Starting with the concept of tradition, the new conservatism, particularly Americanised neo-conservatism (William F. Buckley Jr., God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom”, 1951), has ended up in the cognitive trap of scientism. This has meant that “The Conservative Mind” had the incapacity to see its own ideological faults, in terms of the political and social critiques, and, indeed, the overall ideological critique in terms of systems analysis.

The historical criticism (historiography) of Toryism does the best in plain English terms to demonstrate the shortfall in the thinking. Historically seen, retrospective in time, Tories were monarchists, engaged in a high church Anglican religious heritage, and were opposed to the liberalism of the Whig party. The Conservative model was only ‘recently’ changed – mid-century – with is usually described as ‘Neo-Conservativism’ – the works of Kirk and Buckley Jr., as well as Daniel Bell, Daniel Patrick Moynihan, and Irving Kristol. There is then a disjunction between Toryism and the new conservative model, with neo-conservative writers strangely disparaging modern liberal thinkers of having Tory attitudes; in the same twisted logic of Buckley Jr., in accusing academics of having “supernaturalism”. In terms of critical thinking, it does not take much logical understanding to see that the new conservativism is an argument made of fallacious thinking, and is historically a replay of the ancient Roman “language game” of rhetoric to bewilder the public in accepting the false arguments of the modern industrial/post-industrial “The Power Elite” (C. Wright Mills, 1956).

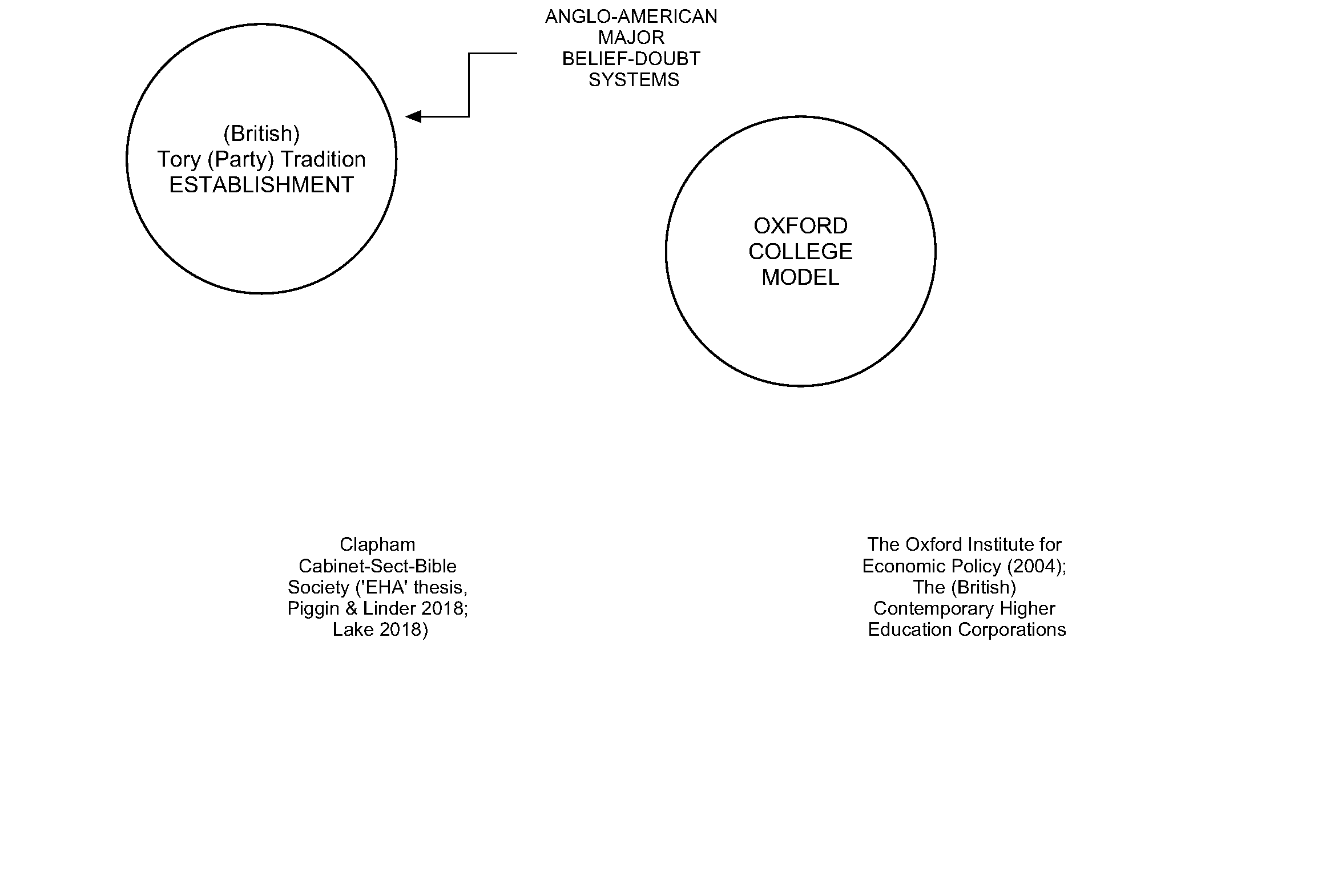

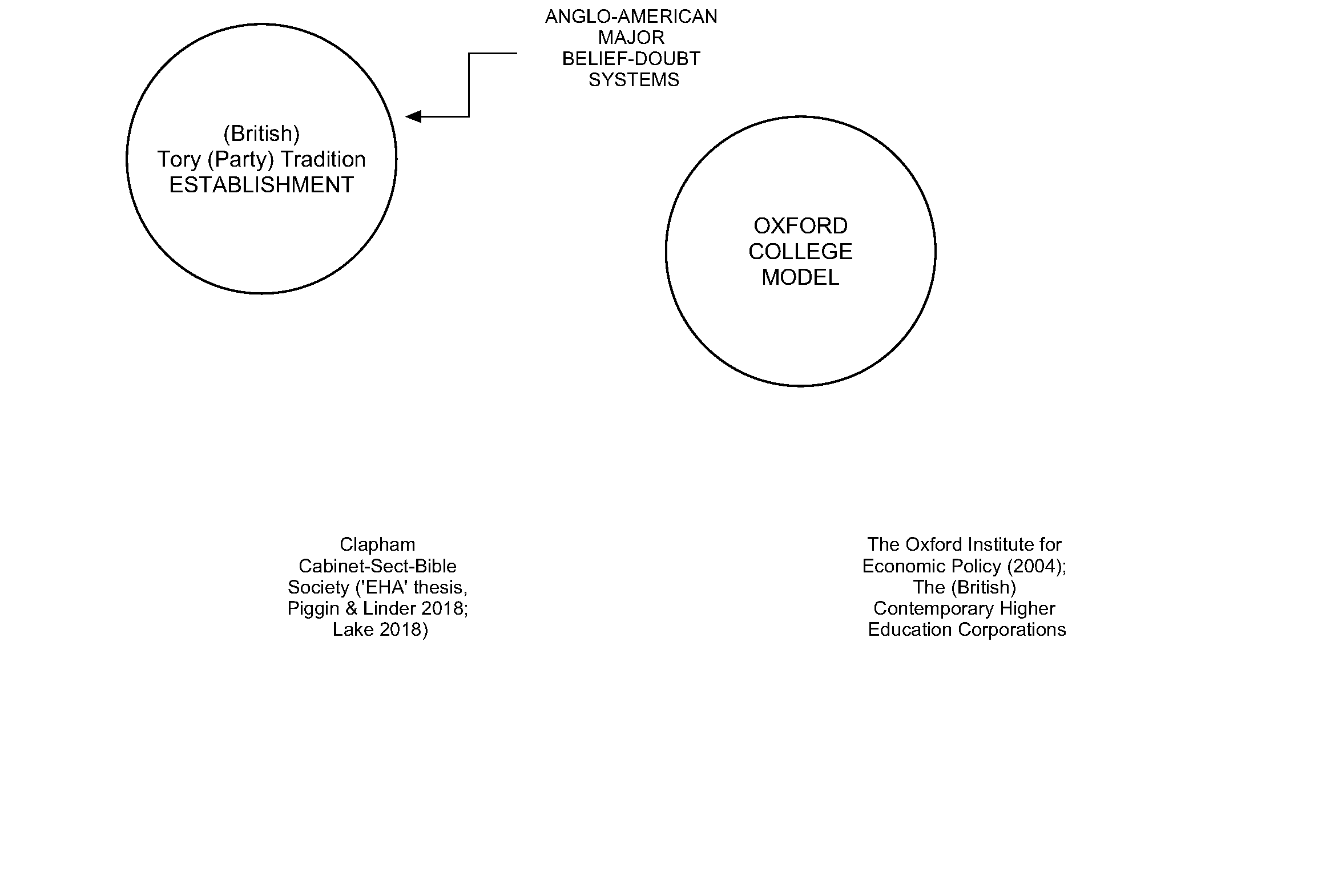

The Oxford College Model is based on the Oxford University Commissioners’ Report of 1852: “The education imparted at Oxford was not such as to conduce to the advancement in life of many persons, except those intended for the ministry.” It is a model of the power elite in the way that the liberal sociologist C. Wright Mills (1956) described it in the American mid-century. Historically, the Oxford College Model has been tied to the Torys’ high church Anglican religious heritage. The link here with the Evangelical world is ambiguous but the intellectual thread is connected in what was called the “Clapham Cabinet” or ‘Sect’ and the history of the Bible Society (‘EHA’ thesis, Piggin & Linder 2018; Lake 2018). The Clapham Sect (technically not a sect but as much part of the established Church of England), or Clapham Saints, were a group of social reformers associated with Clapham in the period from the 1780s to the 1840s. Stuart Piggin & Rob Linder (2018) use the term, Clapham Cabinet, which was made up of its organisational leadership, across Oxbridge and the London Anglican base. The reformers were partly composed of members from St Edmund Hall, Oxford and Magdalene College, Cambridge, where the Vicar of Holy Trinity Church, Charles Simeon had preached to students from the university, and were encouraged by Beilby Porteus, the Bishop of London, himself an abolitionist and reformer, who sympathised with many of their aims. The British and Foreign Bible Society and the Church Missionary Society were associated with the reformers. The Bishop of Oxford in this period (1816-1827) was Edward Legge, Warden of All Souls College, Oxford, from 1817. Catholic emancipation was a long road with strong Puritan and Evangelical opposition, with the markers of the Papists Act 1778, the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1791, the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1793, the removal of the Sacramental Test Act in 1828, and the Roman Catholic Relief Act 1829, followed by “the Tithe War” of the 1830s (the last of legal anti-Catholic discriminations were not removed until the 1920s). In a three-way political competition, the Anglo-Catholic Bishops and Evangelical reformers, stood together in opposition to any appeasement to Roman Catholics; in the same way, in the mid-century Cold War, that American fundamentalists stood together with American neo-conservatives in opposition to any appeasement to global socialists (and in the ideological language of the Americans, “communist”).

The ambiguity, part from cross-institutional connections, was also that the Claphamites, from about the 1830s, often exemplified Nonconformist conscience with many ended up as the Methodists and the Plymouth Brethren thinkers in a broader socio-political movement against Catholic emancipation. The bigot attitude was part and parcel of the growth of evangelical Christian revivalism in England, which had direct links through Anglo-American revivalists, particularly in the American colonial experience of John Wesley, to the American Revivalist Tradition (ART; Buch 1995). Intellectually, at the time, Evangelical Protestant thought necessitated a conspiratorial evaluation of Catholic thought, aided in the growth of American nationalistic thinking. The liberal historiographical critique of mid-century to late century, among the Anglo-American historians, have developed this critique of ART (including Neo-Evangelical scholars). Yet otherwise excelling Evangelical historians continue to “paper over” the intellectual problem – the too high emphasis on doctrine and inability to conceive the ‘dogma’ problem fully in these histories of evangelicalism. It has to be noted that younger “neo-evangelical” scholars, and older scholars in the field are driving the critique (such as the author, Buch, Lucas, 3:1, June 2023, and forthcoming).

The Oxford College Model is historically linked to English Conservativism because of the university’s role during the English Civil War (1642–1649), as the centre of the Royalist party. From the beginnings of the Church of England as the established church until 1866, membership of the church was a requirement to receive an Oxford BA degree from the university and Protestant dissenter were only permitted to receive the Oxford MA in 1871. In contrast, historically, Cambridge University, has been closely associated to radical thought, although the intellectual history is (again) ambiguous. The history of Cambridge is well-associated with several important “anti-establishment” thinkers or mavericks to conventional thought: Isaac Newton, Francis Bacon, Oliver Cromwell, John Milton, Lord Byron, Charles Darwin, Vladimir Nabokov, John Maynard Keynes, Jawaharlal Nehru, Bertrand Russell, Alan Turing, J. Robert Oppenheimer, Ludwig Wittgenstein, and Stephen Hawking. It is a far-too simple, and thus false, to set up an Oxford and Cambridge University Model comparison, but if main collegial networks are the truthful point as several important references to the ‘Oxford School’ or the ‘Cambridge School’, the modelling holds (Randall Collins, The Sociology of Philosophies: A Global Theory of Intellectual Change, 1998). Outside of the intellectual history, what made Cambridge distinct, in the terms social organisational history, was the Cambridge Apostles, founded in 1820. Stephen Toulmin, the philosopher of thinking in this research, was a member, so was Alfred Tennyson, Bertrand Russell, G. E. Moore, and John Maynard Keynes. The Soviet spies Anthony Blunt, Guy Burgess and John Cairncross, three of the Cambridge Five, and Michael Straight were all members of the Apostles in the early 1930s, which would also explain intellectual tensions that had existed with the Oxford establishment.

In the Studies-in-Religion field, there is a strong Cambridge-Birmingham-Lancaster network (English north-west direction) with Ninian Smart, John Hick, and Don Cupitt. The Oxford-Cambridge distinction, however, is even stronger in historiography. Historically, a major network thread in the “Oxford School” has been the conservative ‘Great Man’ tradition, originated in the multi-volume Dictionary of National Biography (which originated in 1882 and issued updates into the 1970s); it continues to this day in the new Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. On the other hand, there is a significant connection between radical thought and the “Cambridge School” of historians. Again, this is ambiguous truthfulness (not straightforward): at Oxford, Christopher Hill, Rodney Hilton (though, moved to Birmingham) but at Cambridge, G. M. Trevelyan, E. P. Thompson, and Eric Hobsbawm. Other places and centres of English radical thought was much closer to Cambridge than Oxford: Dona Torr at University College London and John Saville at Hull University. The work of the American Peter Novick’s, That noble dream: The ‘objectivity question’ and the American historical profession (1988) was published by Cambridge University Press, and can be contrast to the anti-communist liberal historiography of Oxford’s Isaiah Berlin. Indeed, the strength of Berlin’s history of ideas approach was the benefits in “the Oxford idealism”, a much more clearcut set of critiques of ideas in the Continental tradition, which is seen as too highbrow by social historians in the English radical tradition. These historians of a Cambridge bent were not adverse to systems thought but their ideological criticism rode on a perceived social realism from the social historical context in history-from-below. The Cambridge History of Latin America is eleven volume treatment which is much more honest and open to criticisms on Spanish, Portuguese, English Colonialism.

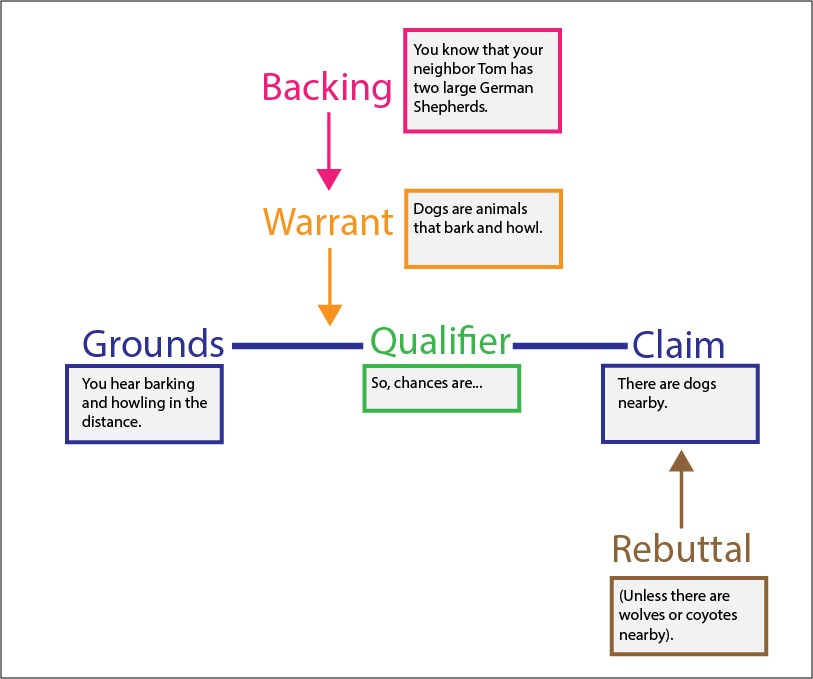

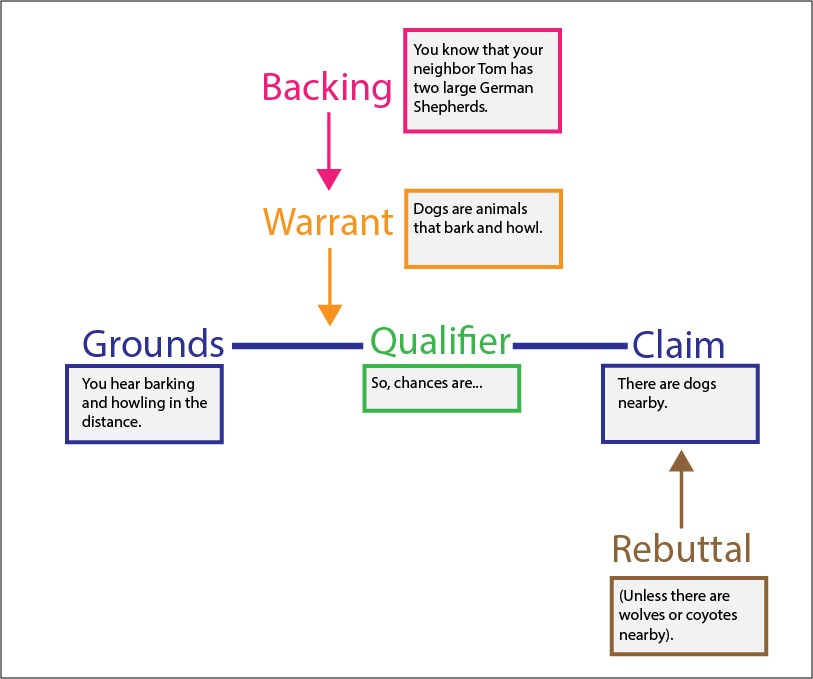

Other fields also reflected in this approach to more contextual and informal logical modes of thought. Stephen Toulmin developed his basic argument of informal logic at Cambridge: the dissertation as An Examination of the Place of Reason in Ethics (1950), where he was influenced by contact with Ludwig Wittgenstein, whose examination of the relationship between the uses and the meanings of language shaped much of Toulmin’s own work. The Toulmin model of argumentation is a diagrammatic six interrelated components used for analysing arguments (The Uses of Argument 1958), and led to “the good reasons approach” a meta-ethical theory that ethical conduct is justified if the actor has good reasons for that conduct, developed in the thinking of Stephen Toulmin, Jon Wheatley and Kai Nielsen. The good reasons approach is not opposed to ethical theory per se, but is antithetical to wholesale justifications of morality and stresses that our moral conduct requires no further ontological or other foundation beyond concrete justifications. The thinking was brought to Oxford when Toulmin was appointed University Lecturer in Philosophy of Science at Oxford University (1949-1954). Toulmin also brought the thinking to Australia when he was Visiting Professor of History and Philosophy of Science at the University of Melbourne (1954-1955). The English modern social and theoretical science has a stronger association with Cambridge.

The Toulmin model of argumentation

There are also important economic developments associated with the paradigm of Anglo-American conservative thought, but there is very little distinction between universities, except for the London School of Economics. The economic thinking coming out of Oxford is seen as conservative or conventional, but that is due to the comparison to the history of the London School, which has always been “radical” in both Left and Right semantics. Indeed, while Oxford desires an overall stable historiography (“conventional wisdom”), London expresses the seesawing between 19th century Free-Market Capitalism (Right), Keynesian “Middle-of-the-Road” Regulation (Left), and Neoliberalism (Right). These cognitive risings and falls take place over decades. The neo-liberal thinking as theoretical works came into being during the 1970s. The Adam Smith Institute, a United Kingdom–based free-market think tank and lobbying group that formed in 1977, was a major driver of the neoliberal reforms. The 1980s saw Thatcherism and Reaganism. Then the economic thinking could not be divorced from shifts in international development theory and trade interest from theorists in the United States. In the 1990s there was the neo-liberal politics of Alberto Fujimori in Peru, and the North American Free Trade Agreement. In the culture-history war since the collapse of communist states (1989-1993), the neoliberal turn was much more about the ideological attack of the neo-conservatives upon the social thinking of mid-century liberals like Walter Reuther or John Kenneth Galbraith or Arthur Schlesinger, than the statistical obscure economic models. The Oxford Institute for Economic Policy was founded (2004), and has been for the last 20 years an independent and non-profit think tank focused on analysis, discussion and dissemination of economic policy issues. However, globally it is still unclear what new economic vision will emerge, but it will, and the historiographical spiral will turn Left in a new way. Unfortunately, the social damage has been done, most significantly in the creation of “The (British) Contemporary Higher Education Corporations”. The damage is significant because a common economic complaint, and the new mantra, are the loss of many specific sub-fields of the humanities and social sciences once taught and researched within the universities, creating a skills shortage for global communities, seeking out a new vision. This will be seen in the third section, examining the Cambridge College Model in further details.

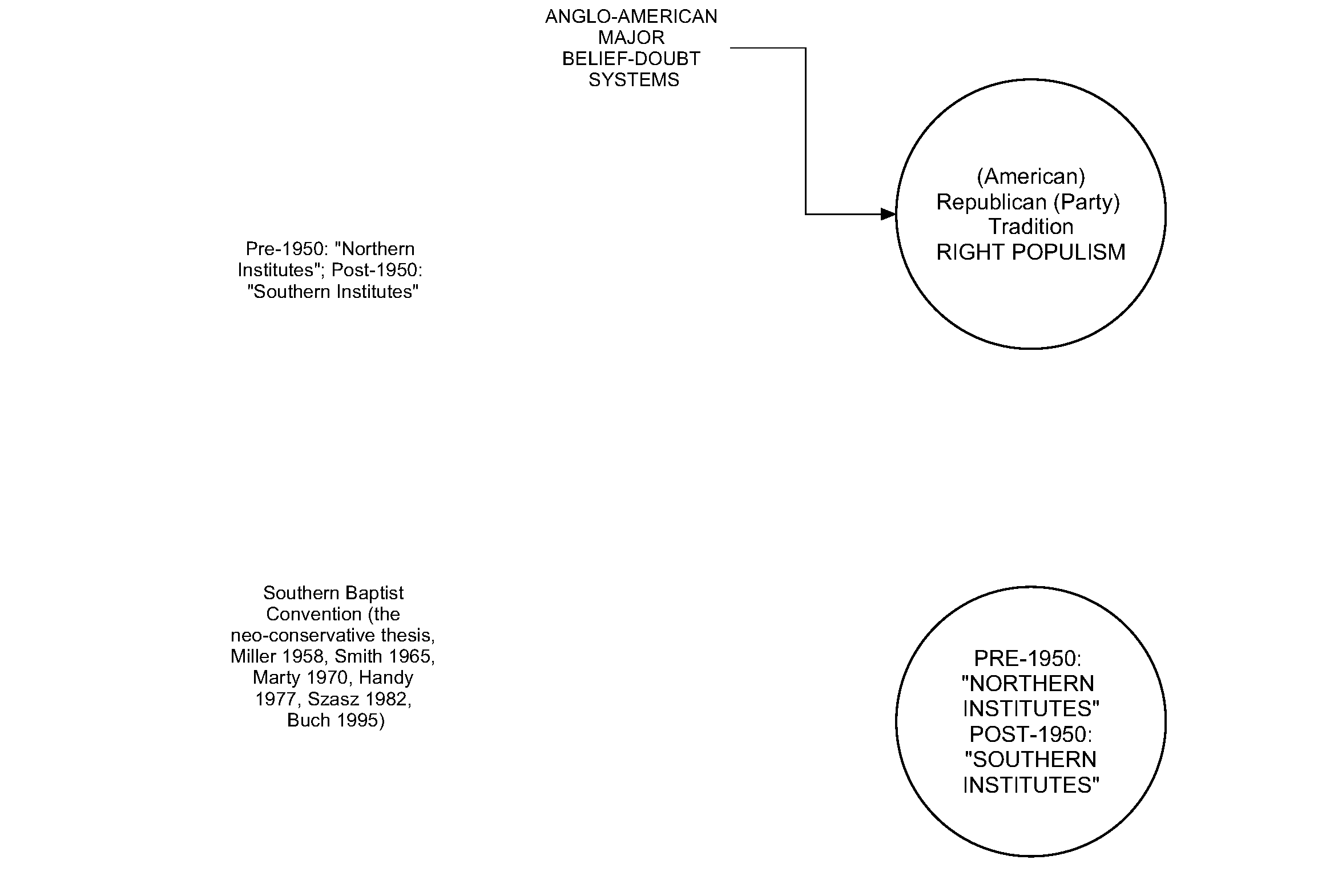

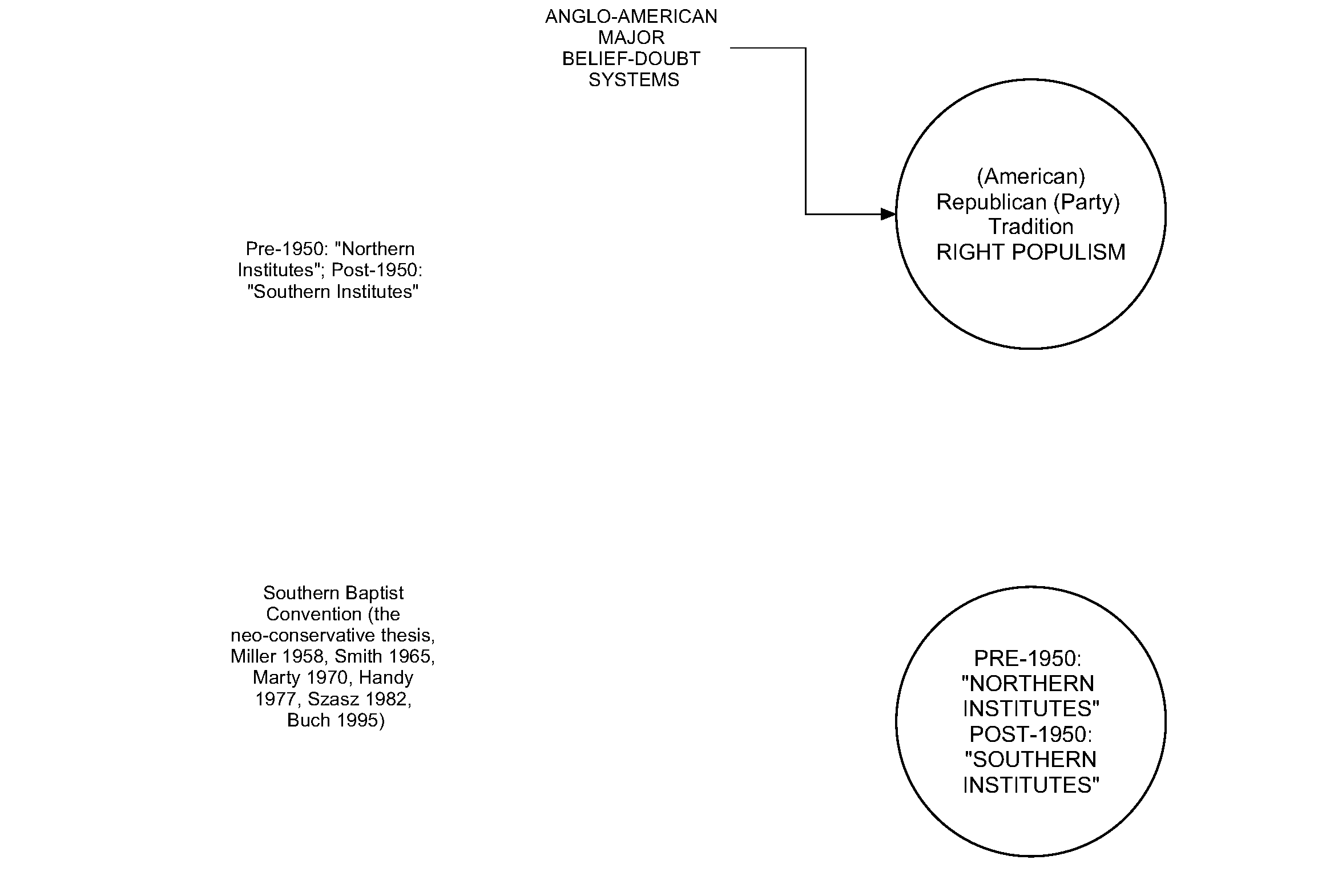

- (American) Republican (Party) Tradition. RIGHT POPULISM.

A basic worldview of the Republican Party (United States), founded in 1854, is difficult to sum up as an accurate summative account, but usually read as the ideology of traditional conservativism. The evidence of the ‘shift thesis’ demonstrated that today’s contextual hermeneutics has made this idea of conservatism a false proposition. The ‘shift thesis’ is a widely held view by American historians that the successes of the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s, meant that the Republican Party’s core base shifted to the Southern states (and intellectually, the Post-1950: “Southern Institutes”), and as the Northeastern states increasingly Democratic (and intellectually reflected the outlook of Pre-1950: “Northern Institutes”). The Republican Party has become the party of right-wing social reaction.

There are several “Southern Institutes” which could be mentioned as closer to the Republican Party, however, because of Buckley Jr.’s 1951 thesis (God and Man at Yale: The Superstitions of “Academic Freedom), universities are marginalised in Republican discussions. Republicans have either attacked the university sector of higher education, or created a new college sector which reflected the traditional conservative curriculum, and often called, “Christian”. In the social reality, but as most cases, these colleges are not ‘traditional conservative’ but the powerhouse of American neo-conservatism. The analysis has to say, “most cases”, as an increasing number of evangelical college communities are fighting back at the colonialisation of “religion” by the Republican Party. Indeed, the excelling evangelical scholars have been, more than half a century back, critics of “American religion”. The smaller but more powerful colleges for the Party are still thinking in terms of neo-fundamentalism, i.e., centralising every argument on the biblical inerrancies. The challenge is that many good evangelical scholars have yet to realise that the modern evangelical apologetic movements of Bill Bright, Chuck Colson (very politically directed under a theological mask for the contemporary Republican ideology) James Dobson, D. James Kennedy, C. Everett Koop, Francis Schaffer, and R.C. Sproul, are eroding the Neo-Evangelical movement in the uncreditable, invalid, and unsound biblical inerrancy claims.

In the middle of this mess of the American South is the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC; the neo-conservative thesis, Miller 1958, Smith 1965, Marty 1970, Handy 1977, Szasz 1982, Buch 1995). I have already explained the role of the SBC in the American neo-conservative thinking in previous publications, but to again recap: Sydney Alhstrom sees anti-intellectualism as a corollary of American revivalism in A Religious History of the American People (1972), and recounted that large elements of the Southern Baptist Convention (SBC), in their opposition to higher education, worked havoc in the academic program of Southern Theological Seminary in Kentucky. The SBC has had a history of forcing academics out of their seminary positions, often due to academics critical study of the scriptures and Church history. It was under these circumstances that Dr. Crawford Howell Toy was pressured to resign from Southern Baptist Seminary in 1879. Martin Marty (1970) saw Toy’s downfall as a pattern that is typical of southern churches. William H. Whitsett, professor of Church History, also at Southern, had the same fate as Toy nineteen years later (1898). When Whitsett condemned the populist Landmark theory, sectarian Baptists, for whom Landmarkism was a sacred doctrine, threatened to withdraw financial support for the seminary.

Such interference in the academic standards of Southern Baptist seminaries has also been evident in the post-1945 period. In 1962, Professor Ralph H. Elliot was dismissed from his position at Midwestern Baptist Theological Seminary when his published book, The Message of Genesis (1962), was deemed ‘liberal’. It is important to note that anti-intellectualism does not pervade all areas of the American Revivalist tradition (ART), but is only a common characteristic of the majority which articulate American revivalism. In the case of Neo-Calvinist and Neo-Evangelical scholarship, it is not a matter of anti-intellectualism, but a matter of pseudo-intellectualism, flawed or out-dated scholarship which continues to avoid relevant contemporary criticism of its assumptions. This is why otherwise many good evangelical scholars are blind-sighted to the intellectual problems in their midst, and what the contemporised Republican Party represents. Much of that comes from a vehement anti-liberal populism. The history of the Convention has only pushed further in this direction in recent years.

Apart from the Republican Party and the Southern Baptist Convention and likeminded colleges, it is difficult to say what educational entities are that generates the worldview in a singular institute or school of thought. This is due, as indicated, that the anti-liberal populism is also anti-intellectual and anti-education in the full understanding of the concept of education. One of the important historical marker as an institutional shaper is “The (American federal) Senate’s Southern Caucus (1964)” in a fight against “Civil Rights” being legislated. The type of thinking has been carried through into the new century with the Tea Party movement (2009) and the House Freedom Caucus (2015), and developing into the ideology of Trumpism (2016-).

There is a link here between the contemporised information technology thinking in relation to social visions of the future, cemented into the mythology of the American Dream, or in cynical disappointment, creating its dystopian mirror vision. These are the conversations and rhetoric of the “The (American) Contemporary Informational and Data Corporations”. There are only a few works which makes the linkages clear, historically Jacques Ellul (1964): the original and formative in a strange but effective Neo-Calvinist and Reformed-Marxist mixture of thought. Nevertheless, the cyber-capitalism is well documented, even if few works described the intellectual relationships with concepts of culture, history and nations.

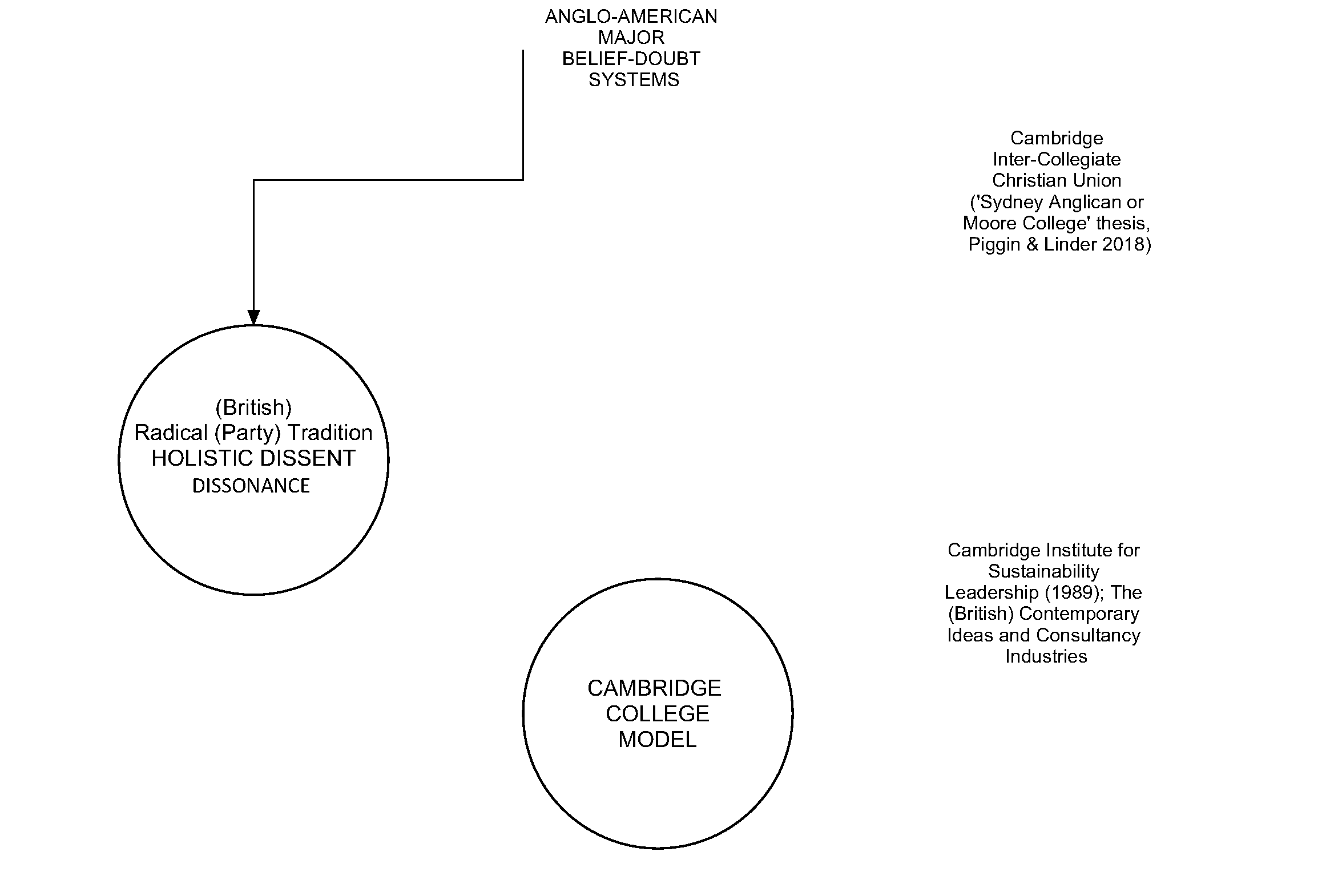

- (British) Radical (Party) Tradition. HOLISTIC DISSENT Dissonance.

English Radicalism or “classical radicalism” or “radical liberalism” had its earliest beginnings during the English Civil War with the Levellers and later with the Radical Whigs, as the retrospective reading of the history in and around the English Civil War. From that development we have, not merely an outdated Whiggish historiography of the 19th century, but the emergence of the new 20th century Progressivist historiography. The new framework is currently evolving in the Postmodern phase. It is not a tradition which will disappear, since philosophically, we can say that somethings are better than others, and since policy says we should not make the better an enemy of the perfect, but the demand for ideological purity is the enemy of social improvement. Hence English Radicalism, or radical parties have been sociologically negative: against the purity of social conservatism, arguing for taking on risks for social change, in the way conservatives continually resist social change to the point of zero (ideologically purity). It is thus ironical that conservatives, still today, accuse the reformist Left of being ‘ideological’. Certainly ‘radicals’ are “ideological” in different variants of: liberalism, republicanism, modernism, secular humanism, antimilitarism, civic nationalism, abolition of titles, rationalism, secularism, redistribution of property, freedom of the press, ‘left-wing causes’, and etc. The ongoing agendas of reforms is what the conservative negatively charge as “being political” with the presumption that most areas of life are generally, on principle, “pre-political”. This is the cause in Conservative blind-side to their own locked-in ideological thinking. Nevertheless, Anglo-American radicalism has its own blind-side.

When conservatives tend to be highly logical in their intellectualism (bubble thinking of logicism), radicals suffer from what I describe as “ Holistic Dissent Dissonance”. The problem is not in taking a holistic approach per se. Nor is the problem in dissenting from convention, or even dissenting from the school of perennial philosophy. It is that there is too frequently cognitive dissonance in the way the poorer radical scholars articulate a positioning of equalitarian holism or any other positioning of radical dissent. Leon Festinger proposed that human beings strive for internal psychological consistency to function mentally in the real world, from his works, When Prophecy Fails: A Social and Psychological Study of a Modern Group That Predicted the Destruction of the World (1956) and A Theory of Cognitive Dissonance (1957). Festinger goes on to say that a person experiences internal inconsistency tends to become psychologically uncomfortable and is motivated to reduce the cognitive dissonance, this then leads to a person justifying the stressful behaviour, either by adding new parts to the cognition causing the psychological dissonance (rationalization) or by avoiding circumstances and contradictory information likely to increase the magnitude of the cognitive dissonance (confirmation bias). More simply, persons avoid admitting mistakes in their thinking, and either rationalise what is poorly rational or blocks emotions by removing the thinking from the situation (context). Psychological dissonance affects the conservatives – the avoidance of admitting mistakes – by the logicism which is something like rationalising in Aristotelian universal spirals (adding cycles upon cycles Infineum). Radicals do not have the traditional recourse and so, despite its universality, the argumentations became fragmented and only signal holism without substantiation. For conservative and radical thinker, none of this is pre-determined, and the solution is the model of communicative rationality (Jürgen Habermas, Communication and the Evolution of society, 1979). In its post-metaphysical model, the argument is:

- called into question the substantive conceptions of rationality (e.g., “a rational person thinks this”) and put forward procedural or formal conceptions instead (e.g., “a rational person thinks like this”);

- replaced foundationalism with fallibilism with regard to valid knowledge and how it may be achieved;

- cast doubt on the idea that reason should be conceived abstractly beyond history and the complexities of social life, and have contextualized or situated reason in actual historical practices;

- replaced a focus on individual structures of consciousness with a concern for pragmatic structures of language and action as part of the contextualization of reason; and

- given up philosophy’s traditional fixation on theoretical truth and the representational functions of language, to the extent that they also recognize the moral and expressive functions of language as part of the contextualization of reason.

The model comes out of post-1945 German radicalism, as the school of Critical Theory. Which is to say that the Anglo-American belief systems of radical and conservative thought could fairly engage, even overlap, before 1945, but after 1945 there was a great disjunction, and this uncoincidentally coincided with the bitter reaction of American neo-conservatism.

It explains the disjunction in the Evangelical World. The European influence in the American Neo-Evangelical movement was to fallibilism from the Barthian reading of Kant. This is directly opposed to the positioning of the American (neo-) fundamentalist movement linked into the American neo-conservatist’s ideological purity (e.g., the purity of Americanism and biblical inerrancy).

The Cambridge College Model has been described above as the contrast with the Oxford Model, however, it might be further suggested that Cambridge had more significant ties to Continental Philosophy than Oxford. That is seen in a Cambridge thinker like Wittgenstein, however, Bernard Williams is better to be said to be an Oxbridge thinker, the philosopher who overcame useless divide between the Anglo-American analytic tradition and the European continental tradition. Williams was able to do that by making links between the Cambridge Wittgenstein’s philosophy of language and Frankfurt Habermas’ philosophy of language, all in a deep historiography influenced by Oxford Berlin’s history of continental ideas.

In the Anglo-American evangelical world, the role of the Cambridge Inter-Collegiate Christian Union provided something of the radical influences from both Anglo-American and German thinking. In the former is the Protestant dissenter’s Arminianism, the Reform’s opposition to the deterministic and highly-doctrinaire classic Calvinism. The latter is more British with the links of Hegelian idealism in liberal evangelicalism, before the American variant of Neo-Orthodoxy killed it, for the United States, from its anti-liberal biases. In the Australian evangelical variant, Piggin & Linder tied the Cambridge outlook to the Keswick movement and the suspicion towards doctrinal fundamentalism in the ranks (2018: 449, 501; 2020: 304). Here is the same link to Protestant dissenter’s Arminianism. I refer this historical description as the Sydney Anglican or Moore College’s thesis. It is a fair institutional self-criticism in the history, particularly as the “Sydney Anglican” historical phenomena. Nevertheless, it misses the deeper layer of the intellectual history, particularly framed in Critical Theory.

The historical debates go to what was sustainable in the intellectual framing. On a wider canvas, ‘secular’ (?), we can look at the Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (1989). It has been for thirty years examining the same intellectual questions for high-end businesses and technology corporations. (https://www.cisl.cam.ac.uk/). Hence, there is a wider ‘secular’ framework in “The (British) Contemporary Ideas and Consultancy Industries”.

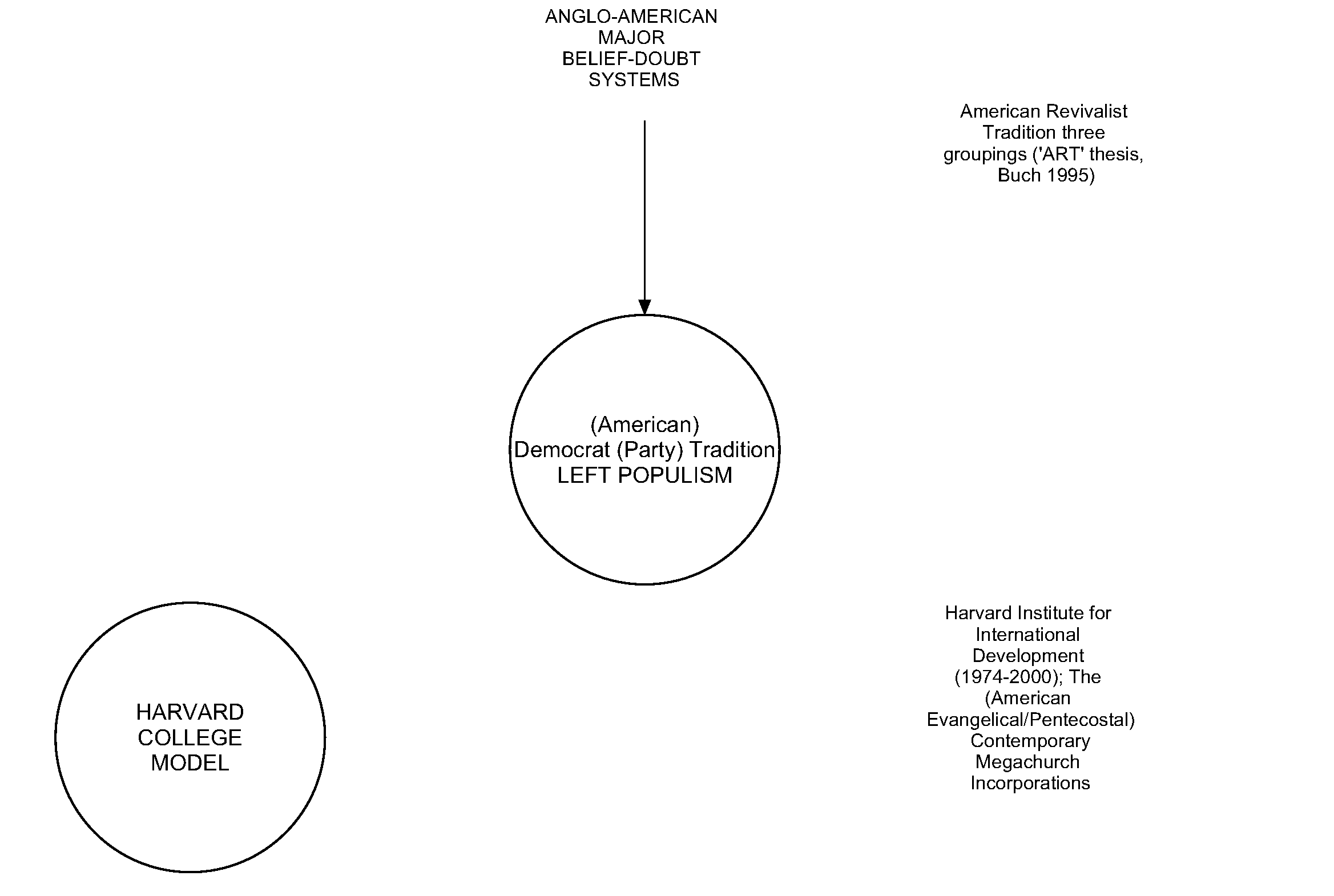

- (American) Democrat (Party) Tradition. LEFT POPULISM.

Many of the descriptions of the American Democrat (Party) tradition and American radicalism are the same as described above for English radicalism. There are important differences. As in the ‘shift thesis’ for the Republican Party, the Democrat Party was not in the camp of “social justice” until the late twentieth century, Kennedy-Johnston politics. Democrat Party has to be remembered as the party of carpetbaggers of the 19th century. Something of the legacy lingers in the Party room. Neither can populist American radicalism escape charges of cognitive dissonance, the same cases of English Radicalism. Historian Gordon S. Wood articulated the differences for American Left Populism and Establishment Democrats from their English counterparts in the 1993 Pulitzer Prize book, The Radicalism of the American Revolution (Vintage Books). The American revolution was a completely different to the English Civil War, and has some, but not all, overlap in the concept of a Puritan Revolution. Wood argues that the American colonists appropriated Whig absolute ideals of ‘liberty,’ different to the articulations of the English Civil War. The American variant ultimately came to represent the unity of personal liberty and public liberty, and a residue of representation in a ‘natural aristocracy’. Differences are drawn out by writers like Henry James. The difference is subtle but go to a power play on informal (America) and formal (British) characteristics.

Most significant, is that these differences are moral characteristics. The question is who was more respectable? The practical informality of the Americans, which the British saw as coarse (disrespectful), or the ancient formality of the British, which the Americans saw as hypocrisy (disrespectful). The question arose from the emergence of the Harvard College Model. Daniel Walker Howe (1970) articulated the tradition of Harvard Moral Philosophy in connection to the Unitarian ‘revolution’ at Harvard (The Unitarian Conscience, Harvard University Press). That ‘revolution’ of thought is the rejection of orthodoxy and dogma for informal logic, or as said today, critical thinking. This kind of thinking was reflected in the short-lived Harvard Institute for International Development (1974-2000). Liberal organisations have been plagued on the American scene from anti-liberal biases which arises from the culture(s).

This is what we have today in the crisis of Americanised evangelicalism. ‘The battle of bible’ of the 1970s and 1980s was only the shaper end, theologically, of intellectual framings, which goes to, one side, outside of traditional evangelicalism, Unitarian-Universalist Thought, and the other side, a hard-driven Calvinistic (neo) fundamentalist thinking, all within the United States. This research began as the doctorate of the current author (‘ART’ thesis, Buch 1995). The current crisis of evangelicalism extends back in a history to the 1960s, and also back to the American neo-conservative paradigm of the Cold War 1950s. There are three ART groupings (American Revivalist Tradition, Buch 1995). American revivalism is expressed by the three distinct characteristics of the American Revivalist tradition; biblicalism, anti-intellectualism, and mechanisation of the Christian faith. Biblicalism is the ideology which gives the biblical canon an exalted authority over the life of the believer.

All aspects of belief, doctrine, thought is expected to conform to precepts that biblicalists claim are recorded and supported by the 66 books of scripture. Biblicalism is based on the belief that the whole biblical canon is a harmonious revelation of God, the Word of God. Although most biblicalists would claim that there are areas of scripture that are vague in their meaning and may be given differing interpretations, the fact that the biblicalists make themselves the interpreters of the divine Word of God means biblicalism, like all sacred book traditions, ends up being the tyranny of the believers over themselves. The believer is locked into a cyclical existence where belief is said to come from the Word of God which is itself the belief of the believer. In such an existence, the process of hermeneutics is avoided.

Anti-intellectualism is the second characteristic present in the American Revivalist tradition. Anti-intellectualism is a state of mind which suspects complex and abstract concepts in favour of dogmatic and poorly-constructed beliefs. It has generally involved the slander, censorship, or prohibition of certain academics and their writings. Richard Hofstadter identifies anti-intellectualism as a significant part of the American culture in Anti-intellectualism in American Life (1966). American anti-intellectualism frequently appeared through the use of American apocryphal stories which were recorded in denominational periodicals, as well as the over-the-top criticism of non-evangelical paradigms in literature (usually paperbacks, tapes, and then digital podcasts) of the Apologetics Industry.

Mechanisation of the Christian faith is the third characteristic of the American Revivalist tradition. The American Revivalist tradition sought to implement various techniques to bring about a ‘revival’, and in the process, reduced the Christian life to a series of techniques in evangelism and discipleship. In this way, the Christian faith was merely mechanical, the elements of faith (belief, prayer, worship, etc.) all locked into a machine-like plan. In the post-1945 period, American revivalism became consumed by searching out revivalistic techniques in the form of evangelistic methodologies. There were many American evangelical writers who claim to have discovered the “techniques” that Jesus used with his disciples. To understand the technological nature of the American Revivalist tradition, one needs to turn to the sociological works of Jacques Ellul, Professor of History and Sociology of Institutions at the University of Bordeaux, and a European evangelical in the Calvinist tradition. Ellul formed the thesis that the predominant characteristic of the contemporary human condition is, in the French definition of the word, technique. Technique, once a tool developed for science, is now a mindset that dominates the affairs of humanity; a mindset where the question of “How it works” becomes all important while the question of “Why it is so” becomes increasingly irrelevant. Method is valued more than content.

In the 21st century, then, “The (American Evangelical/Pentecostal) Contemporary Megachurch Incorporations” has become the expression of the paradigm. The current research analysis is based on a large volume of American liberal historiography during the twentieth century, hovering between the consensus and conflictual schools, with a focus on Richard Hofstadter (1963, 1965). It demonstrates that a megachurch can only exist as a business organisation, with membership growth as the prime reason for that existence.

That the megachurch problem is sourced in the history of the American culture, and some might disagree, having described the Australian Pentecostalism as indigenous. The ‘indigenous’ view is supported by Rocha & Hutchinson (2020: 3-4; 2002: 26), Barry Chant (1999: 39), Byron Klaus (Klaus in Dempster, Klaus & Petersen 1999: 127), and Philip Hughes (1996: 3). It is posited that Australian Pentecostalism is local rather than sourced from overseas missions. However, the American history described and explained the phenomenon of the global megachurch. In Australia, the local megachurch phenomena of the 1970s and 1980s were a product of the American revivalist tradition (Buch 1994). The tradition is a historical series of parochial mass movements which shaped the American ideological narrative, and then exported as Americanism (as in American modernism). Mark Hutchinson and John Wolffe (2012) attempt to link the new direction of the ‘indigenous’ view in the era of 1870-1914 with what they describe as a ‘New Global Spiritual Unity’. There is some bearing here, but it is more accurate to say that it was a vision of world mission undergirded by western cultural values rather than being a true vision of global unity. That new vision had to wait for the mid-twentieth century sociology revolution. Sam Hey’s recent works (2011, 2016) has greatly helped to understand the Australian experience of megachurch in the sociologies of Peter L. Berger (1973), Rodney Stark and William S. Bainbridge (1987), Robert Wuthnow (1988), Wade C. Roof (1999), and Scott Thumma and Travis Dave (2007). The new sociology of religion has done much to have shaped the understanding of and for the megachurch, which for the large part is American, and framed in the American culture.

- (English) Colonial (‘institutes’) Tradition. MISSION AND APOLOGETICS.

In popular fiction – novels, television, films – the landscape of London is the signifier of colonialism. This is true as references to “London Institutes”. The “London Missionary Society” (the traditional Protestant mission thesis, Piggin & Linder 2018: 107-15) is at the top of the list. Piggin and Linder refer to the ‘triumphalist spirit of the missionaries’ (110). The ‘religious’ adjoins to the ‘secular’ in City and Guilds of London Institute (Imperial College, 1878). The Institute is an educational organisation in the United Kingdom. Founded on 11 November 1878 by the City of London and 16 livery companies – to develop a national system of technical education, the institute has been operating under royal charter (RC117), granted by Queen Victoria, since 1900. Today, one of it main historical functions is as a registered charity, thereby funding itself as the awarding body for City & Guilds and ILM qualifications, offering many accredited qualifications mapped onto the Regulated Qualifications Framework (RQF).

Here is another great social problem of our times, “The (Anglo-American) Contemporary Public Relations Businesses”. The world of charities and higher education have succumbed to the great mistakes of public relations thinking: 1) dumbing down the narrative of a singular message, 2) engage criticism as unintelligent Apologetics, the system of defence by diverting criticism into fallacious propositions, and 3) produce neo-colonial arguments:

1.0. The Dumbing Down Thesis is well-established, and yet there are ‘religious’ and secular’ readers who act as if it is a surprising new thesis. However, the literature is volumes and sharper to the accurate point than the dismissive institutional apologetics:

1.A. On higher education there is Kenneth Minogue, emeritus professor in political science at the London School of Economics, Alan Smithers, professor of education at Liverpool University, and Frank Furedi, writer and sociologist at the University of Kent, Canterbury (Where Have All The Intellectuals Gone? Continuum, 2004);

1.B. On Secondary Schooling: John Taylor Gatto’s Dumbing Us Down: The Hidden Curriculum of Compulsory Schooling (1991, 2002), where for 30 years there has been nothing new in the criticism of the conventional institutional outlook:

-

-

- It confuses the students. It presents an incoherent ensemble of information that the child needs to memorize to stay in school. Apart from the tests and trials, this programming is similar to the television; it fills almost all the ‘free’ time of children. One sees and hears something, only to forget it again.

- It teaches them to accept their class affiliation.

- It makes them indifferent.

- It makes them emotionally dependent.

- It makes them intellectually dependent.

- It teaches them a kind of self-confidence that requires constant confirmation by experts (provisional self-esteem).

- It makes it clear to them that they cannot hide because they are always supervised.

1.C. The Sociology from Below: in the well-known sociologist Pierre Bourdieu’s (1930–2002) book, Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste (1979), proposed that, in a society in which the cultural practices of the ruling class are rendered and established as the legitimate culture, said distinction then devalues the cultural capital of the subordinate middle- and working- classes, and thus limits their social mobility within their own society.

1.D. Sociology from Above: the social critic Paul Fussell touched on the same themes but speaks of “prole drift” in Class: A Guide Through the American Status System (1983) and focused on them specifically in BAD: or, The Dumbing of America (1991). The difference here is that Fussell’s work can be read as a critique of the ruling class thinking or as the ruling class thinking apologetics: the American neo-conservatism.