Minister for State Development, Infrastructure, Local Government and Planning (the Planning Minister)

PO Box 15009, City East, Queensland 4002

Submission as Feedback on Kurilpa Sustainable Growth Precinct Temporary Local Planning Instrument No.1 of 2023 (Brisbane City Council) – DSDILGP

Dear Stephen Miles [Planning Minister],

cc. Environmental Minister

cc. Health Minister

Please accept this document as our submission to Queensland Government, as well as the Brisbane City Council as their LOCAL PLANNING INSTRUMENT NO.1 OF 2023.

The argument backbone of the submission is an analytic literature review of 44 scholarly works in the last 20 years (2003-2023), which demonstrates that the Council and State Government is globally out of touch with the current best thinking and practice for urban design, urban planning, the housing demand (crisis), suburban sustainable living and population management.

1.0 Community Opposition to Density Planning

The overall argument is of historical-sociology, important, since the bureaucrats who prepared The Kurilpa Sustainable Growth Precinct Temporary Local Planning Instrument No.1 of 2023 (Brisbane City Council) seem to suffer history blindside-ness. There is considerable contemporary urban sociology criticism of short-visioned town/city/urban planning, or the process of de-planning in ideologically neo-conservative-committed municipal governance, explained in this document. The instrument of Local Planning Instrument No.1 of 2023 is effectively an argument of totalitarian free-market governing de-planning. It will not open up a housing market to relieve the housing crisis in the way that the political argument of Council promises. This will become clear as the community opposition to (hyper) density planning is explained, and why the free-market de-planning approach that Council is seeking is not the view of the wider sets of communities in Brisbane, but simply allows construction developers a free-hand in their preferred business model.

First, though, some history in urban sociology needs to be referenced, and other historical references will be throughout the document. Mace (2016: 243) referenced the early opposition to 20th-century mass suburbanisation in the United Kingdom from the architect Ian Nairn (1955[1]) and social commentators Gordon and Gordon (1933[2]), and later in the 1960s, Lewis Mumford (1968[3]). The problem identified was the link between the growth of mass-consumption and mass movement into suburban areas, creating a de-functional kind of community, generally unlistened and misunderstood in the governance process. The distinction between the intercity suburbs and the city’s suburbs “proper” in the conversations-debates was artificial. The intercity suburbs have always been suburbs and the pattern of suburbanisation was always the same: releasing of land as estates by government and private residential developments. All suburbanisation happened in the presence of industry – rural and manufacturing – and the pattern only changes as the suburban sprawl moved outwards in distance. The distinction then that the intercity suburbs gained has been as a gateway to the CBD district for suburbs further out. Quoting Mumford, Mace points out the mass movement of suburbs, “caricatured both the historic city and the archetypal suburban refuge: a multitude of uniform, unidentifiable houses, lined up inflexibly, at uniform distances, on uniform roads, in a treeless communal waste, inhabited by people of the same class, the same income, the same age group, witnessing the same television performances, eating the same tasteless pre-fabricated foods, from the same freezers, conforming in every outward and inward respect to a common mold …” (Mumford, The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects, p. 486).

City planning has long involved real estate interests opposing regulation and wide and intelligent planning, and this false narrative of real estate has degenerated in the opposition between the dynamics of social housing construction and private housing densification processes in the suburbs, with a few ignored methods being proposed for resolution (Maleas 2018:73). McCabe (2016:137) articulated the historical opposition to good urban planning in the context of the Plan of Chicago where the false narratives abound from real estate developers and planners, claiming that best-practice municipal planning is esoteric or impractical: “The conversion of the real estate interests to city planning is the crux of the whole movement.” The false narrative which the Brisbane City Council has picked up in the purpose of Local Planning Instrument No.1 of 2023 is to develop into an emphasis on the growing internal diversity of suburbs and inner-city gentrification (Moos, et al. 2015: 84). On this exact point, Moos (2015) sees “the lack of congruence between largely suburban constituencies and the promotion of what are still seen in some quarters as planner-driven urban lifestyles” (Preville 2011, Sewell 2009).

As Raynor, Mayere, & Matthews (2018a:1058) stated:

“Australian urban consolidation policy has employed a similar set of rationales to smart growth and focuses on managing rapid population growth and compromising higher density housing provision with a historical preference for suburban, detached housing (Newton and Glackin, 2014). Despite international policy support for consolidation strategies, urban consolidation remains contentious and often inspires ‘almost systemic’ community opposition (Searle and Filion, 2011: 11).”

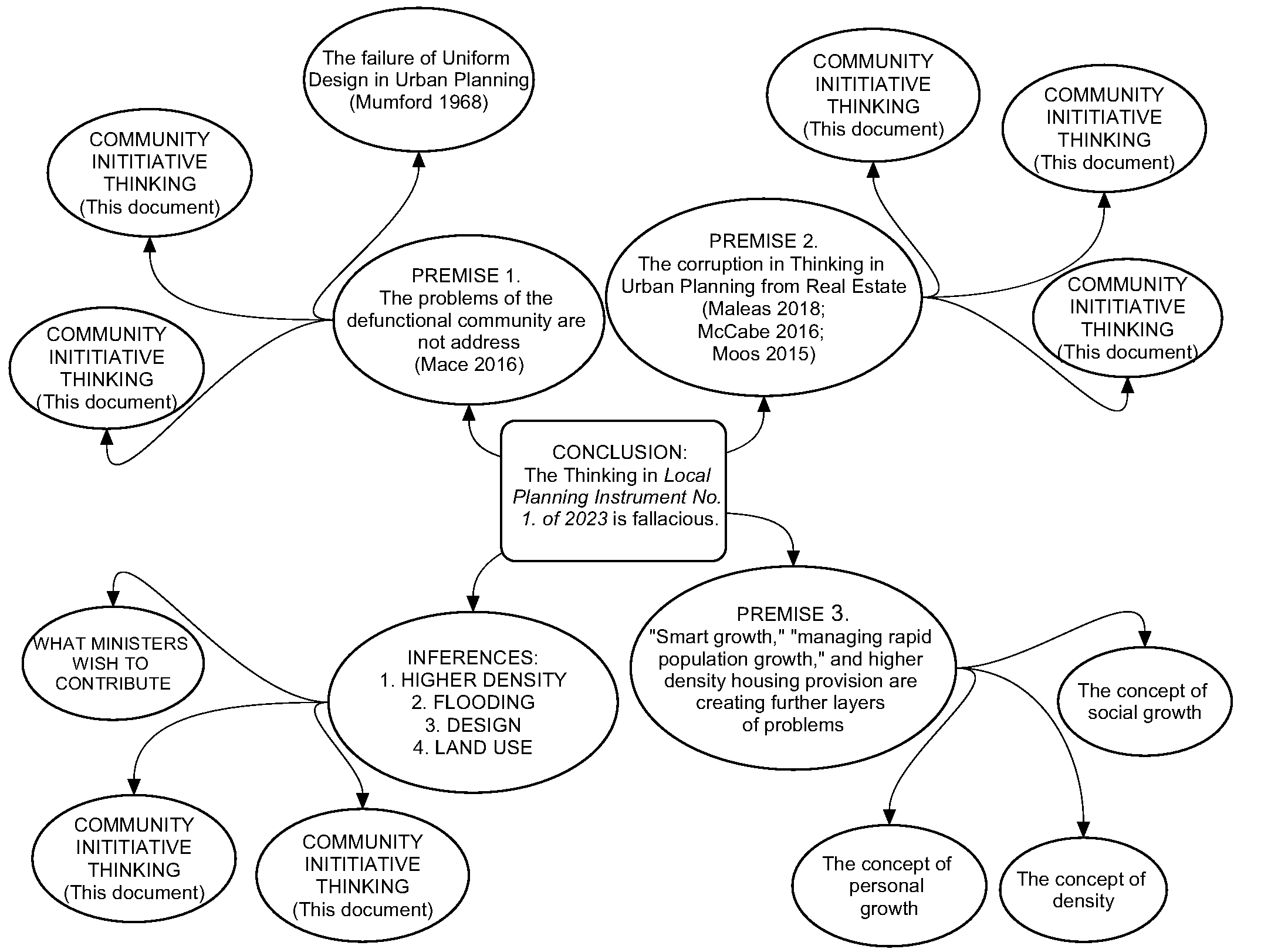

In the Rationale critical thinking diagram, it is in black and white, evidenced and unmasked, and yet the Council and State Government remain deaf, to the electorate, and eventually facing the political backlash. And yet the Council and State Government remain deaf.

Figure 1: Rationale critical thinking diagram, Mind Map: Why the Local Planning Instrument No. 1 of 2023 fails.

As Shasore (2018:189) explains, as the skewed and historic bubble thinking, there is still:

“Dissatisfaction at [the UK] ministry and with the methods of the housing division perhaps helps to explain [Arthur Trystan] Edwards’s use of a voluntary association as a vehicle for housing reform, free from covert politicking and internal lobbying [mid-century]. He bitterly recalled, for instance, that when ministry officials expressed doubt about the twelve dwellings per acre limit, ‘[Raymond] Unwin whipped up his parliamentary henchmen to make a protest against the suggested abandonment of the humane standards of life which after years of propaganda housing reformers had succeeded in establishing’.”

Thwarting best-practice municipal planning is not new from councils and governments; and the bureaucrats and the politicians are fools if they think that, after a century, and more, of such tactics and strategies, the educated population will tolerate it anymore, especially with the clear evidence of climate change and Europe and North American burning before our eyes.

The same tactics and strategies are, though, being practice by Australian municipal authorities. Troy (2018: 1339) notes of Sydney’s politics of urban renewal: “Meriton was heavily criticised for not only trying to maximise their development potential by pushing design boundaries, but also maximise returns by building as cheaply as possible, with the inevitable outcome being the construction of poor-quality buildings.” This is exactly the nature of the Brisbane City Council’s Local Planning Instrument No.1 of 2023, and the state government should not continue to buy into the false narratives. Poor quality buildings have implications with disruptions to community, and increased energy and water consumption and usage, thus exacerbating the regions health problems, economic costs and schedule blowouts to government department budgets and operations.

There are five technical arguments of urban sociology in this document: the climate-change (and related health issues) agenda, the spatial scoping, the sufficient and comprehensive policy, the sufficient and comprehensive planning, and the community valuing as the general valuing and ethos of our historical timing in the 2020s (i.e., we no longer tolerate the institutional ‘bullshit’ – a technical term in applied philosophy, see Harry G. Frankfurt’s infamous essay, Bullshit, Princeton University Press, 2005).

Overall, the climate-change argument here is that, on top of the problem of rezoning for laxing height restrictions, changes in the building codes, and to create new codes (Gurran, & Phibbs 2016: 63), were aimed to ameliorate the changes in global climate, and increasing height in buildings will only work against those meagre climate change and health efficiency service measures: increasing shadows and the cold in periods of dramatic lower temperatures, and increasing hot airflows between larger buildings and increase airconditioned energy needs in periods of dramatic higher temperatures. There is a clear policy’s argument which effectively and comprehensively tie together all of the other arguments. Everything is tied together as policy failure (and thus the solution) in the final cost to the community, and government and council simply bulwarking what communities want and need. Legal battle between the leaders of a community of low-income families that wanted to construct an affordable housing project and local government that tried to resist the construction are well-known (Mc Cawley 2019: 596n34). What is also well-known are municipal game-playing on the truth about policy failures in many national context (Philifert 2014: 73). The stated policy might be effective and comprehensive but the loss of integrity is seen in the planning stages and implementations. There are simply, but perhaps legally corrupt, laxation of plans and failure to implement publicly-stated policies ( Gurran, & Phibbs 2016: 63; Mc Cawley 2019: 596n34; Philifert 2014: 73). The terms of politically democratization by the community, “refers to changes in the system of power and decision-making procedures that resulted in a ‘pluralisation’ of power relations and relations to power that opened spaces of freedom and places of debates while expanding the possibilities of conflict management’” (Philifert 2014:73, citing Béatrice Hibou 2011, p. 2). March (2010:115) sums up the problem of the Australian policy historical setting from Melbourne:

“The widespread emergence of the new form of medium density housing divided planning academics, activists and practitioners. A small but influential group of modernists, mainly from architectural backgrounds, believed good design would solve both social issues and desires to provide high quality family housing. On the other side of this divide stood opposition to redevelopment of ‘slums’ via demolition of existing housing stock, and the supporters of the suburbs (Yule, 2004: 161). Yet another group were the staunch supporters of planned suburban development as the ideal Australian housing form (Stretton, 1971). Even today, debate about the suburbs versus higher density living continues (Gleeson, 2006).”

The false narratives of governments and councils (as mentioned above) are the attempt of these governing entities to mask themselves from public scrutiny that they are out of ideas and have become the victims of the unscrupulous developers’ game-playing. To get around the problem of the political narrative, there has been abusive employment of consensus theory. As Ormerod & MacLeod (2019: 320) stated:

“Contributions to this body of thought [political rhetoric] have undoubtedly disclosed some limits to consensus models of planning and formal political engagement while also revealing seemingly neutral practices like ‘good governance’ to be deeply politicized (Brown, 2015; MacLeod, 2011; Swyngedouw, 2009). Nonetheless, adhering to a post-political narrative in turn risks positing a troubling binary between consensus and conflict: one that envisages places to be governed through a ‘police order’ in opposition to ‘proper political’ undertakings that disrupt this very order. These disruptions are often viewed to foreshadow the potential for a more progressive democracy (cf. Dikeç and Swyngedouw, 2017; Rancière, 1999; Swyngedouw, 2011). Such a binary suffers ‘… from an overly limited definition of what counts as politics proper, as well as a failure to understand consent as fundamentally political. In so doing, it undermines its own ability to understand how consensus is won and whose interests it serves.’ (Mitchell et al., 2015: 2636)”

There is also the spatial argument in the other overlapping arguments to which is significantly connected to community costs and rental affordability. The community’s argument here is for the state and municipal authorities to share its effective and comprehensive valuing. As Sager (2018: 456) argued:

“Intentional communities have a permanent need to stress their otherness. Consequently, when spatial planning is part of their defence strategy, the plans are likely to demonstrate difference from mainstream society. This makes intentional community planning agonistic by nature. Strife must be continuing to underline opposition to conventional living (Pløger, 2004). The combination of hybridity and non-conformity is the reason why planning by intentional communities can contribute something new to planning theory.”

It should be straight forward for the State Government Minister to understand; strife is how the urban-suburb community is feeling (see figure 1). Further comments are to follow in relation to the climate-change agenda, the spatial scoping, the sufficient and comprehensive policy, the sufficient and comprehensive planning, and the community valuing, and applied to two specific problems which arise from the Council’s Local Planning Instrument No.1 of 2023 – (1) higher (hyper) density residential building, and (2) the future and well-predictable flooding in the riverside neighbourhood (un)planned area. Added to the examination are the true valuing in (3) community design excellence, (4) community land use strategies, and (5) community urban planning.

1.1 Higher density residential buildings

Ideologically, outside the vested-interest of an elite wealthy, the community argument is against higher (hyper) density residential buildings. Raynor, Matthews, & Mayere (2017: 1520), speaking to the Brisbane scene, cites Dodson and Gleeson (2007) and Ruming and Houston (2013) on the issue of urban consolidation, and relating genuine fears of “diminished quality of life, neighbourhood character and property values once densification occurs”. Raynor, Matthews, & Mayere (2017) concern is for “social representations employed by city shapers to understand, promote and communicate about urban consolidation”. The article reads as a lesson on critiquing urban propaganda, and they state, “…that urban consolidation debates and justifications diverge significantly from stated policy intentions and are based on differing views on ‘good’ urban form, the role of planning and community consultation and the value of higher density housing”; and [We] “conclude that there is utility and value in identifying how urban consolidation strategies are influenced by the shared beliefs, myths and perceptions held by city shapers.” The problem is that academics in this narrow field of urban sociology do not appreciate the depth of the political criticism from wider fields of social science, such as political studies, studies-in-religion and historiography. Hence, whether meaning to or not, Raynor, Mayere, & Matthews (2018b: 1057) have come across a little too sympathetic to political needs of government and council rather than that of Queensland communities to which they argue they understand but do not have the voice of the community; although their academic ‘neutral’ rhetoric did somewhat depart in referring to “Understanding these narratives and their influence is fundamental to understanding the power-laden manipulation of policy definitions and development outcomes.” This document makes a stronger argument and cites those urban sociologists who refer to the stronger economic critique masked by government and council, such as from Troy (2018: 1329):

“Australia has long had a deeply speculative housing property market. Arguably this has been accentuated in recent years as successive governments have privileged private-sector investment in housing property as the key mechanism for delivering housing and a concurrent winding back of direct government support for housing. This has occurred through a period in which urban renewal and flexible planning regulation have become the key focus of urban planning policy to deliver on compact city ambitions in the name of sustainability. There has been a tendency to read many of the higher density housing outcomes as a relatively homogenous component of the housing market. There has been a comparative lack of critical engagement with differentiated spatial, physical and socio-economic outcomes within the higher density housing market. This [Troy’s] paper will explore the interactions between flexible design-based planning policies, the local property market and physical outcomes. Different parts of the property development industry produced distinctive social and physical outcomes within the same regulatory space. Each response was infused with similar politics of exclusion and privilege in which capacity to pay regulated both access and standard of housing accessible, opening new socio-economic divisions within Australia’s housing landscape.”

Again, can the Minister ignore what is so publicly understood in dealing with the Council’s Local Planning Instrument No.1 of 2023. This is particularly true with the climate-change argument. The link between environmental sustainability and low-density suburban development is not lost on the leading urban sociologists (Newton 2010:82). Newton’s work (2010) is very technical and is able to draw out the planning limitations for greenfield, brownfield and greyfield development but none of it supports at all the arguments of the Council’s Local Planning Instrument No.1 of 2023. Newton is rationally and wisely hopeful that the society can create a “transitions arena of stakeholders (institutions and communities) to formulate a new model for greyfield precinct regeneration that can help redevelop those existing but poorly performing neighbourhoods of Australia’s major cities into more sustainable places?” This is hopeful if government and council does not remain deaf. As Wright (2010: 1) points out the:

“Consolidation of the urban fabric is seen as a means to reduce energy consumption and thus greenhouse gas emissions. However, the relationship between high-density housing and low energy use is not automatic. Although urban consolidation can lead to lower transport energy use, research shows that planners, designers and policy makers may not have sufficiently taken into account built-form energy use by different housing types.”

The return of affluent population groups into gentrifying inner urban areas, the market for higher (hyper) density residential buildings, is rationalised on good public transport accessibility in a spatial sense, but this has only been seen for such neighbourhoods with other extending problems, such as street parking, and the planned transport alleged solutions are distributed into other suburbs usually at a greater distance from metropolitan centres (Scheurer Curtis, & McLeod 2017: 912). It does not at all improve public transport accessibility in a spatial sense in the way that Brisbane City Council promises. This is one of many policy failure around the argument for higher (hyper) density residential buildings. Planning intentions from such de-regulated policies might be originally good (Nethercote 2019: 3394), but they become closed-minded when planning goes wrong, such as the case of creating isolated, heat-attracting, and unattractive and unused “islands” in the form of enclosed, large, courtyards not well-maintained (Patel, Shirish Alpa Sheth, & Neha Pancha 2007: 2725). The urban heat island effect referenced in Australia’s State of the Environment 2021 Report, officially released in 2022, https://soe.dcceew.gov.au/urban/pressures/climate-change.

The policy failure is largely driven by the market demand of the affluent population groups, as opposed to a vision of integrated communities and it recognizes the importance of affordable housing to such a vision. The latter was the Victorian government’s housing policy a few decades ago (Wood, Berry, Taylor, & Nygaard (2008: 274).

1.2 Flooding riverside neighbourhood plan area

The most severe ideological criticism of government and council is in the sphere of flood and water management and that has had a long legacy in the history of Brisbane. Water engineering (surface water management to control flash flooding and protect underground aquifers) is a very important element in Greenstructure planning (Beer, Delshammar, & Schildwacht 2003: 133-4). Dr Cook (2019:72-75) has challenged the effective use of the Council powers to manage flood risk, even as the Council is powerful as a kind of modern city state. Cook (2022) has well-demonstrated that the continual policy of the Brisbane City Council extends to the extremely poor thinking in water management across governance in Australia. The Council’s Local Planning Instrument No.1 of 2023 is another example of the extremely poor thinking in that the Council has yet to respond to Cook’s challenge that higher (density) building will only make the Brisbane River flooding worse. Ignoring the challenge puts the government and the council on the wrong side of history as evidence in the climate-change argument are dramatically increasing. In fact, we as a society are supposed to be beyond the debate and should be participating in what is expertly seen as a global emergency. Allowing The Council’s Local Planning Instrument No.1 of 2023 to pass would be a great policy and de-planning failure.

1.3 True community design excellence

This document submission does offer positive suggestions. There are projects which have become successful and sustainable as community design excellence. They are draw from principles of ‘civic design’ (Shasore 2018: 175). However, here having sufficient knowledge of design and construction principles means going much deeper in the historical sociology to see where assumptions built into principles have led into problematic outcomes (Moos et al 2015: 69). To the horror of poor, uncritical, thinkers, it necessitates a deep examinations of common presumptions in matters of gender, “race”, ethnicity, and wealth, in relation to workspace and the space for sustainable suburban living. Indeed, it goes to criticism of the precognitive “miserable science”: economics and its presumptions. We need to be aware that the knowledge-base that may have solutions is also the same knowledge-base that led us into the problems in the first place. We need not, though, repeat the cognitive mistakes. When we have been substantively told the truth, Minister, we cannot plea ignorance for when policy or implementation failures occur. From the Canadian perspective, Moos et al (2015: 64-5) expresses well what we what we already should know and act upon in historical sociology:

“Suburbs that developed in metropolitan Canada post-World War II have historically been depicted as homogeneous landscapes of gendered domesticity, detached housing, White middle-class nuclear families, and heavy automobile use. We find that key features of this historical popular image do in fact persist across the nation’s contemporary metropolitan landscape, particularly at the expanding fringes and in mid-sized cities near the largest metropolitan areas. The findings reflect suburbanization into new areas, point to enduring social exclusion, and recall the negative environmental consequences arising from suburban ways of living such as widespread automobile use and continuing sprawl. However, the analysis also points to the internal diversity that marks suburbanization today and to the growing presence of suburban ways of living in central areas. Our results suggest that planning policies promoting intensification and targeting social equity objectives are likely to remain ineffective if society fails to challenge directly the political, economic and socio-cultural drivers behind the kind of suburban ways of living that fit popular imaginings of post-World War II suburbs.”

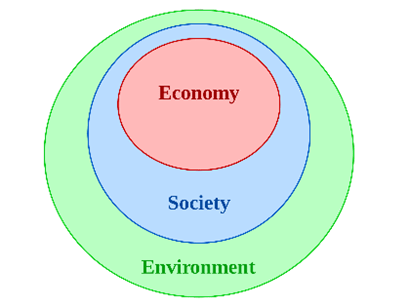

Figure 2: Necessary Scoping in Thought for Urban Planning and Sociology

Again, across the document, the truth could not be plainer for the Minister’s reading. The argument is repeated across the volumes of scholarly literature which draw the same broad conclusion and that conclusion goes to what design excellence is in the 2020s, and what it is not. Troy (2018: 1329) stated:

“There has been a tendency to read many of the higher density housing outcomes as a relatively homogenous component of the housing market. There has been a comparative lack of critical engagement with differentiated spatial, physical and socio-economic outcomes within the higher density housing market. This paper [Troy’s] will explore the interactions between flexible design-based planning policies, the local property market and physical outcomes. Different parts of the property development industry produced distinctive social and physical outcomes within the same regulatory space. Each response was infused with similar politics of exclusion and privilege in which capacity to pay regulated both access and standard of housing accessible, opening new socio-economic divisions within Australia’s housing landscape.”

Nelson (2009: 40) points out the problem of the singular political messaging of “The new urbanism [which] would design neighbourhoods so that households of all life stages have the option of living in a single neighbourhood.” Randall & Baetz, (2015: 361) described this singular messaging as the “”Proponents of smart growth and neo-traditional design models of development purport that these characteristics will lead to residential development that is more sustainable than the conventional suburban model.” However, the design models are being critical re-examined in its reported successes. In the last 20 years academics have made similar criticism of the Queensland case, but the criticism is too bland and lacks the sharp philosophic critical statements of the sociological problem in Queensland politics; to which is being drawn out in this document. In the critique of Raynor, Mayere, & Matthews (2018a: 1059), in relation to the statutory South East Queensland Regional Plan 2009–2031, and with the Council’s Local Planning Instrument No.1 of 2023 in mind, only conclude that despite political rhetoric that in keeping with community-based policy outcomes (Frew et al., 2016)., the Queensland government urban policies are “…often criticised for not achieving the benefits it purports to deliver, for instance by lowering the standards of building regulation and by reinforcing the general climate and consequences of neoliberal reform (Frew et al., 2016).”

The language, however, has to be put much stronger in philosophical terms on the political cognition when it comes to the critical problems identified in the climate-change argument. The list of problems includes those from Coutts, Beringer, & Tapper (2007: 477):

“Alterations to the natural environment, resulting from the physical structure of the city and its artificial energy and pollution emissions, interact to form distinct urban climates (Bridgman et al. 1995). These urban climates can often be undesirable, causing increases in air pollution and aiding the formation of urban heat islands (UHI). Urban warming can have substantial implications for air quality and human health (Stone and Rodgers 2001). Factors generating the UHI are believed to include emissions of atmospheric pollutants that increase longwave radiation from the sky and/or increased absorption of shortwave radiation (depending on the pollutant), anthropogenic heating, reduced horizontal airflow due to increased friction, absorption and retention of energy from solar radiation due to canyon geometry, reduced longwave loss due to limited sky-view factor, and reduced evapo-transpiration from vegetation removal, which is a natural cooling mechanism (Tapper 1984; Oke 1982; Stone and Rodgers 2001). Urban structure, intensity of development, and type of building material can also influence UHI intensity, which suggests that UHI may be more a product of urban design rather than, as commonly assumed, the density of development (Stone and Rodgers 2001).”

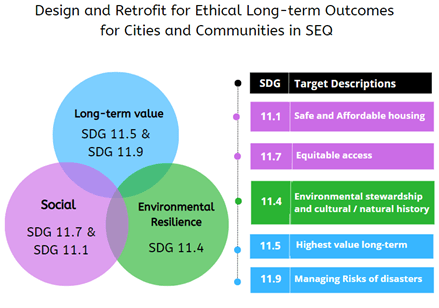

Ensuring urban design leads the planning and development is offered as a solution to counter UHI and promote environmental outcomes for health, economic and recreational/tourism benefits. This has been identified in the “We the peoples declaration of South East Queensland” following a series of roundtables structured on the world leading united nations Habitat 3 framework and alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

The climate-change argument clearly demolishes the Council’s argument for higher (hyper) density building in Kurilpa area, as elsewhere.

Since the QUT Kelvin Grove higher (hyper) density residential development, the university’s academics have been the principal advisors for the Queensland Department of Housing in the thinking on the construction of a mix of educational, research, commercial and community buildings in the decade 2005-2015 (Hammonds 2005: 1). That has been extremely poor because the academics have been caught in the narrow boxes of technical specialisation, since they lack the wider and deeper multidisciplinary education in other fields of sociology, philosophy, and history. The machine, technical, thinking skews the outlook of the academics. There needs to be a re-reading of the basic issue in the way Nankervis (2003: 315) demonstrates:

“ A basic issue in measuring anything is to identify, describe or define the concept or object. It is here that the problem begins. In the broad conceptual sense, planning is simply making decisions about how to act in the future, generally with the implication that a series of actions will be coordinated towards a particular end. One dictionary definition notes planning or a plan as ‘(noun); tabulated statement or scheme; project, design or way of proceeding’. Or; ‘(verb, transitive); arrange beforehand’. The inclusion of the concept ‘town’ or ‘urban’ (or regional), merely locates the decisions in space, though town planning is not exclusively about space. As Badcock (1984) argued, we need to ‘put space in its place’, and so town planning should not focus on space, but the human activities taking place within space.”

As Cheshire (2018: 10) stated, “the first problem with the British planning system: it has no rules.” Ormerod & MacLeod (2019: 319) also confirms the existence of the philosophical problem: “In recent decades, and drawing lessons from the critique of high modernism (Dear, 1986), scholars of urban planning have been motivated to formulate conceptual approaches facilitating a deeper involvement of the public in actively planning and designing places (Fainstein, 2000; Healey, 1996).” The criticism refers to the unplanning in the Local Planning Instrument No.1 of 2023. Other parts of the literature speak to the urban poor who need to participate in formal planning processes (Galuszka 2019: 144). However, from the current government and council perspective the issue remains narrowly one of land usage and zoning. A result of this is where an economic success for one government department, such as local planning, will have negative and economic blowouts in other government departments, such as the government departments of environment & science, water, and health. Hence is this really an economic success for the state and local governments outright.

1.4 True community land use strategies

Outside of the power-hold of government and council, the wider community has its own solutions. Allen (2011: 358) points to CIAM urbanism (Californian institutional architectural management?) which is not pure abstract modernism but successfully demonstrated commitments to local natural landscape during 1950s and 1960s in general, in Berkeley’s plans and the Francisco Bay Area. Historically, Meen, & Nygaard (2011: 3107-8) argue that the rigours of the land use planning system means that supply is inelastic, particularly, “…where states that face the most stringent zoning regulations (notably the coastal states) experience low supply elasticities and more price volatility (Glaeser et al , 2008; and Goodman and Thibodeau, 2008). This is not an argument for de-regulation nor de-planning, but according to Meen, & Nygaard (2011: 3108):

“In summary, history and geography may have strong effects on local inequalities in development, but it is not clear whether or not they exert a stronger or weaker impact than planning policy, although the two are not entirely distinct at the local level. Yet, given that national policies are common to all areas, local markets can be analysed to examine whether differences in supply elasticities are partly attributable to differences in existing land use patterns, which may have been laid down over many years.”

What is inferred is an uneven political competition between developers and the interests of the broader-but-local community in land use strategies for housing. Even in the ICT networked Mega-City which was supposed to ameliorate climate-change threats, the prospect of new stage development is “…characterized by suburbanization [and] could signify for multifunctional land-use deurbanization” (or, as Van den Berg, 1982, in planning of such a Mega-City-Region, term it, ‘desurbanization’; Priemus & Hall 2004: 339). Hilber & Schöni 2016: 291) concluded from the literature that:

“The United States is characterized by fiscal federalism and an enormous variation in the tightness of land use restrictiveness across metropolitan areas. The key policy concern across the country is homeownership attainment and the key policy to tackle this issue is the mortgage interest deduction (MID). This policy backfires in metropolitan areas that are prosperous and where land use is tightly regulated— “superstar cities”—because, in these places, the policy-induced demand increase mainly pushes up house prices. The MID increases homeownership attainment of only higher-income households in metropolitan areas with lax land use regulation.”

Again, the argument for the Minister not to approve the Local Planning Instrument No.1 of 2023 could not be clearer. In this argument there is no binary between intercity zoning and outer suburb concerns, that is a complete false narrative and is all parcelled into the same residential land termed urban sprawl (Kulmer, Koland, Steininger, Fürst, & Käfer 2014: 57). There are no secrets here. The public call has been made by urban sociologists.

Murdoch (2004: 52-3) in a precise argument called, “Putting Discourse in Its Place: Planning, Sustainability and the Urban Capacity Study”, rejected the

“…‘predict and provide’ approach to planning for housing [a phrase first popularized by the Planning for the Communities of the Future, Council for the Protection of Rural England (CPRE), UK Department of the Environment, Transport and the Regions (DETR 1998)]. It also emphasized the need to increase the responsibility of regional and local planning authorities in deciding how to best meet housing needs in each region. In undertaking this task, these authorities should look closely at the allocation of previously developed sites and the scope for a ‘sequential’ and ‘phased’ approach to the provision of new housing. All these proposals had recently been advocated by the CPRE in the hope that localistic pressures for the preservation of green land would gain greater influence in the planning process.”

The failure of the UK approach is precisely the same characteristics of Queensland’s statutory South East Queensland Regional Plan 2009–2031. As Arias, Draper-Zivetz, & Martin (2017: 98) examined in the San Francisco Bay Area, the Puget Sound region in Washington State, and the Minneapolis-Saint Paul, Minnesota, the “…efforts [of planning authorities] did not add up to a comprehensive community engagement strategy, especially as compared with other case study regions.” And as D’Apolito (2012:xx) stated, “a truly comprehensive regionalism would address the interrelationships between land use, transportation, and other features of the infrastructure, and concomitant social and economic disparities… Land use and education are [the] issues” (emphasis added; D’Apolito cited Basolo and Hastings 2003: 450, and Norris 2001). The Minister’s decision, again, could not be clearer based on the evidence.

1.5 True community urban planning

The whole document here has shown what true community urban planning details in opposition to the Council’s Local Planning Instrument No.1 of 2023. There is no shortage of information and data to make wise and intelligent decisions on behalf of the substantive local community interest. For example, Lenth, Knight & Gilgert, (2006: 1445), who detail issues on conservation value: (1) densities of songbirds, (2) nest density and survival of ground-nesting birds, (3) presence of mammals, and (4) percent cover and proportion of native and non-native plant species. This is nothing new after a century or more in urban planning, and there are many global examples of community-initiative planning: Baltimore Plan (Leclair-Paquet 2017: 517n2); City Quay scheme (1979-81), the Royal Institute of Architects of Ireland Silver Medal for Housing, “greatly loved by its house-proud tenants” (McManus 2011: 280).

The Queensland government appears (to date) to ignore the historical sociology argument. This has led to ignorance – whether wilful or not – of mistakes made in the United Kingdom decades ago in housing policies (Barker 2019:69). This decade of 2020s goes to deeper problems of food security and climate change. Basso (2018: 111) only a few years ago stated:

“Only recently, however, the way in which food-related policies and strategies could renew the themes and tools of public space design and, more generally, of open spaces, has been questioned. From this point of view, is it possible for us to put forward another research question: can the “food system” help define new fields for urban design? Some scholars have already pointed out that, since 2005, urban agriculture has progressively shifted from being only a policy subject to being a design subject, too (Viljoenet et al., 2015). There are many instances confirming this trend. To date, for example, the Carrot City website (https://www.torontomu.ca/carrotcity/) has collected more than 100 design experiences related to urban agriculture, highlighting the wide variety of proposed solutions: from community initiatives, housing, and rooftops up to the designing of individual ‘components’ that can enrich and diversify open space configurations and uses.”

In this light, Dr Cook’s (2019: viii) call for a rethink on the riverine territory more in line with the indigenous outlook is not outlandish.

First, however, government and council need to re-think and re-design community education. The UK mistakes in the housing policy were generated in the public square through a set of false narratives on measuring and modelling the impact of planning and other public interventions for economic outcomes (Bramley, & Leishman 2005: 2213). Ultimately, what is needed is community education in the deep philosophy pertaining to visions of, and for, language, society and urban sociology. A very good example is Griggs, & Howarth (2008: 125) in addressing paradoxical concerns in the politics of urban sociology:

“Very generally, to put it in terms borrowed from Rousseau, the paradox concerns the difficulties of mediating and reconciling the gap between ‘the will of all’ (the sum of particular wills) and the ‘general will’ (the moment of universality that is common to each particular will), thus highlighting the tension between the free pursuit of private self-interest and those activities directed at the realization of the common or public good (Rousseau, 1978). But while Rousseau (as well as Hegel and Marx in their different ways) strived for a complete overcoming of this split in any legitimate political order, where individual freedom would coincide with community and the good of all, he was of course deeply pessimistic about its realization in actual political orders. Indeed, it is clear that the tension pinpointed by Rousseau is still pertinent today, even though in contemporary theory it admits of a range of possible permutations and expressions. In rational choice theory, for example, it is manifest in the difficulties of reconciling the logic of individual, rational self-interest with the logic of collective action, as the perceived costs of the latter can outweigh its perceived benefits, or because the goods can be achieved without acting in concert at all (Olson, 1965).”

Again, this is not an argument for cynical resignation. Our hope lies in better ways of being cognisant of the issues. The various arguments of this document ought to bring the Minister to an intelligent decision upon the Local Planning Instrument No.1 of 2023.

2.0 Conclusion

Incorporating the five technical arguments discussed in this document, for true community urban planning, land use strategies. design excellence, climate resilient neighbourhood plans and adequate and varied housing density buildings, solutions should involve adequate urban design with participatory governance. This can be visualised through a trifecta framework of 1. long term economic value, 2. social, and 3. environmental framework aligned to the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Reference for image: https://www.unaa.org.au/2023/02/07/united-nations-habitat-35-declaration/ (figure 3 below).

A further consideration is that the Queensland Treaty and Education Minister would be good to engage for the input and voice of indigenous peoples which it references. This submission sets out to demask or de-ideologize policy narratives in urban planning. Philosophy professor at UQ, Donald Vandenberg, argued that the first step is to the understanding the forces at play in the public arena. However, ideology always serves the interests of those in power, and, now with the focus on the Brisbane Olympic Games in 2032, it will become increasingly harder for those wishing to challenge the ideology with rational thought and evidence. The tension between inner city and suburban development will continue to be a political argument of ‘totalitarian free-market government de-planning’ no matter the evidence to the contrary. The Minister, though, has the agency of the honesty, not to accept false narratives and bad policies.

The educated public is a notion that resonates with the community, and Lewis Mumford in the 1970s continues to be deeply influential for the community. Many community geographers have seen the lively debates on the relationship between the city and space: ‘we need to put space in its place’. The whole object of town planning ought to be a focus on the human activities taking place within space and not space per se. Leibnitz argued that space is nothing but a series of relations which is in stark contrast to the Newtonian conception of absolute space as a container into which all sorts of object are placed. There needs to be a conversation around such philosophic thought, and perhaps as part of re-thinking and re-designing community education.

The community is fed up with the game playing political rhetoric of institutional bullshit from those who are too lazy to think a little deeper about the kind of city our children will inherit. There well may be political backlash if the Minister gives the Kurilpa Sustainable Growth Temporary Local Planning No 1 of 2023 a tick of approval but at least the ‘TRUTH’ has been presented to the Minister which is a positive outcome of the submission. It remains to be seen. Will logic, evidence and argument prevail?

Figure 3: Necessary Scoping in Thought for Urban Planning and Sociology: United Nations Sustainable Development Goals

3.0 Bibliography and References

Allen, P. (2011). The End of Modernism? People’s Park, Urban Renewal, and Community Design. Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, 70(3), 354–374. https://doi.org/10.1525/jsah.2011.70.3.354

Arias, J. S., Draper-Zivetz, S., & Martin, A. (2017). The Impacts of the Sustainable Communities Initiative Regional Planning Grants on Planning and Equity in Three Metropolitan Regions. Cityscape, 19(3), 93–114. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26328354

Badcock, B. (1984). Unfairly Structured Cities. Oxford: Blackwell.

Barker, K. (2019). Redesigning Housing Policy. National Institute Economic Review, 250, R69–R74. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48564806

Basso, S. (2018). Rethinking public space through food processes: Research proposal for a “public city.” Urbani Izziv, 29, 109–124. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26516365

Beer, A. R., Delshammar, T., & Schildwacht, P. (2003). A Changing Understanding of the Role of Greenspace in High-density Housing: A European Perspective. Built Environment (1978-), 29(2), 132–143. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23288812

Berg, L. van den, Drewett, R., Klaassen, Rossi, A. and Vijverberg, C.H.T. (1982). Europe, A Study of Growth and Decline, Oxford: Pergamon.

Bramley, G., & Leishman, C. (2005). Planning and Housing Supply in Two-speed Britain: Modelling Local Market Outcomes. Urban Studies, 42(12), 2213–2244. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43197241

Bricocoli, M., & Cucca, R. (2016). Social mix and housing policy: Local effects of a misleading rhetoric. The case of Milan. Urban Studies, 53(1), 77–91. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26146232

Bridgman, H., R. Warner, and J. Dodson (1995). Urban Biophysical Environments. Oxford University Press.

Brown, W. (2015). Undoing the Demos: Neoliberalism’s Stealth Revolution, New York: Zone Books.

Cheshire, P. (2018). Broken Market Or Broken Policy? The Unintended Consequences Of Restrictive Planning. National Institute Economic Review, 245, R9–R19. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48562309

Cook, Margaret (2019). A River with a City Problem: A History of Brisbane Floods, University of Queensland Press.

Cook, Margaret (2022). Cities in a Sunburnt Country: Water and the Making of Urban Australia, Cambridge University Press

Coutts, A. M., Beringer, J., & Tapper, N. J. (2007). Impact of Increasing Urban Density on Local Climate: Spatial and Temporal Variations in the Surface Energy Balance in Melbourne, Australia. Journal of Applied Meteorology and Climatology, 46(4), 477–493. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26171916

D’Apolito, R. (2012). Can’t We All Get Along? Public Officials’ Attitudes toward Regionalism as a Solution to Metropolitan Problems in a Rust Belt Community. Journal of Applied Social Science, 6(1), 103–120. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23549001

Dear, M. (1986). Postmodernism and planning. Environment and Planning Development: Society and Space 4: 367–384.

Dikeç, M. and Swyngedouw E. (2017) .Theorizing the politicizing city. International Journal of Urban and Regional Studies 41(1): 1–18.

Dodson, J. and Gleeson B. (2007) The use of density in Australian planning. Paper presented at the 2007 State of Australian Cities Conference, Adelaide, 28–30 November 2007.

Edwards, Arthur Trystan (1921). The Things Which Are Seen: A Revaluation of the Visual Arts, London.

Edwards, Arthur Trystan (1944). Style and Composition in Architecture: An Exposition of the Canon of Number, Punctuation and Inflection, London.

Edwards, Arthur Trystan (1947). The Things Which Are Seen: A Philosophy of Beauty, 2nd edition, London.

Fainstein, S. (2000). New directions in planning theory. Urban Affairs Review, 35: 451–478.

Frankfurt, Harry G. (2005). Bullshit, Princeton University Press.

Frew, T., Baker D. and Donehue P. (2016). Performance based planning in Queensland: A case of unintended plan-making outcomes. Land Use Policy, 50: 239–251.

Galuszka, J. (2019). What makes urban governance co-productive? Contradictions in the current debate on co-production. Planning Theory, 18(1), 143–160. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26677440

Glaeser, G. L., Gyourko, J. and Saiz, A. (2008). Housing supply and housing bubbles, Journal of Urban Economics, 64, pp. 198

Gleeson, B. (2006) Australian Heartlands: Making Space for Hope in the Suburbs, Crows Nest: Allen & Unwin.

Goodman, A. C. and Thibodeau, T. G. (2008). Where are the speculative bubbles in US housing markets?, Journal of Housing Economics, 17, 117-137.

Gordon J. and Gordon C. (1933) The London Roundabout. Edinburgh: Harrap.

Griggs, S., & Howarth, D. (2008). Populism, Localism And Environmental Politics: The Logic and Rhetoric of the Stop Stansted Expansion Campaign. Planning Theory, 7(2), 123–144. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26004248

Gurran, N., & Phibbs, P. (2016). “Boulevard of Broken Dreams”: Planning, Housing Supply and Affordability in Urban Australia. Built Environment (1978-), 42(1), 55–71. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44132319

Hammonds, A. (2005). Kelvin Grove Urban Village. Environment Design Guide, 1–10. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26148283

Healey P (1996) The communicative turn in planning theory and its implications for spatial strategy formation. Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science 23: 217–234.

Hilber, C. A. L., & Schöni, O. (2016). Housing Policies in the United Kingdom, Switzerland, and the United States: Lessons Learned. Cityscape, 18(3), 291–332. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26328289

Hibou, B. (2011). Le mouvement du 20 février, le Makhzen et l’antipolitique… Cahiers du CERI, May, pp. 1-11.

Jackson, K. (1985). Crabgrass frontier: the suburbanization of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press.

Kulmer, V., Koland, O., Steininger, K. W., Fürst, B., & Käfer, A. (2014). The interaction of spatial planning and transport policy: A regional perspective on sprawl. Journal of Transport and Land Use, 7(1), 57–77. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26202672

Leclair-Paquet, B. (2017). The ‘Baltimore Plan’: case-study from the prehistory of urban rehabilitation. Urban History, 44(3), 516–543. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26398769

Lenth, B. A., Knight, R. L., & Gilgert, W. C. (2006). Conservation Value of Clustered Housing Developments. Conservation Biology, 20(5), 1445–1456. http://www.jstor.org/stable/3879136

Mace, A. (2016). The suburbs as sites of “within-planning” power relations. Planning Theory, 15(3), 239–254. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26098748

MacLeod, G. and Johnstone C. (2012). Stretching urban renaissance: Privatizing space, civilizing place, summoning community. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research 36:1–28.

Maleas, I. (2018). Social housing in a suburban context: A bearer of peri-urban diversity? Urbani Izziv, 29(1), 73–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26446684

March, A. (2010). Practising theory: When theory affects urban planning. Planning Theory, 9(2), 108–125. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26004197

McManus, R. (2011). Suburban and urban housing in the twentieth century. Proceedings of the Royal Irish Academy. Section C: Archaeology, Celtic Studies, History, Linguistics, Literature, 111C, 253–286. http://www.jstor.org/stable/41472822

McCabe, M. P. (2016). Building the Planning Consensus: The Plan of Chicago, Civic Boosterism, and Urban Reform in Chicago, 1893 to 1915. The American Journal of Economics and Sociology, 75(1), 116–148. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43818683

Mc Cawley, D. G. (2019). Law and Inclusive Urban Development: Lessons from Chile’s Enabling Markets Housing Policy Regime. The American Journal of Comparative Law, 67(3), 587–636. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26866522

Meen, G., & Nygaard, C. (2011). Local Housing Supply and the Impact of History and Geography. Urban Studies, 48(14), 3107–3124. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43082026

Mitchell, D., Attoh K. and Staeheli L. (2015). Whose city? What politics? Contentious and noncontentious spaces on Colorado’s Front Range. Urban Studies 52: 2633–2648.

Miller, Mervyn (1992). Raymond Unwin: Garden Cities and Town Planning, Leicester.

Moos, M., Kramer, A., Williamson, M., Mendez, P., McGuire, L., Wyly, E., & Walter-Joseph, R. (2015). More Continuity than Change? Re-evaluating the Contemporary Socio-economic and Housing Characteristics of Suburbs. Canadian Journal of Urban Research, 24(2), 64–90. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26195292

Mumford L. (1968). The City in History: Its Origins, Its Transformations, and Its Prospects. San Diego, CA: Harcourt Brace International.

Murdoch, J. (2004). Putting Discourse in Its Place: Planning, Sustainability and the Urban Capacity Study. Area, 36(1), 50–58. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20004357

Nairn I. (1955). Outrage: On the disfigurement of town and countryside, London. Architectural Review 117: 361–460.

Nankervis, M. (2003). Measuring Australian Planning: Constraints and Caveats. Built Environment (1978-), 29(4), 315–326. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23288882

Nelson, A. C. (2009). Catching the Next Wave: Older Adults and the ‘New Urbanism.’ Generations: Journal of the American Society on Aging, 33(4), 37–42. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26555694

Nethercote, M. (2019). Melbourne’s vertical expansion and the political economies of high-rise residential development. Urban Studies, 56(16), 3394–3414. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26958648

Newman, P. and Kenworthy, J. (1999). Sustainability and Cities: Overcoming Automobile Dependence. Washington, DC: Island Press.

Newton, P. W. (2010). Beyond Greenfield and Brownfield: The Challenge of Regenerating Australia’s Greyfield Suburbs. Built Environment (1978-), 36(1), 81–104. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23289985

Newton P. and Glackin S. (2014) Understanding infill: Towards new policy and practice for urban regeneration in the established suburbs of Australia’s cities. Urban Policy and Research, 32(2): 1–23.

Oke, T. R., 1982: The energetic basis of the urban heat island. Quarterly Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society, 108, 1–24.

Olson, M. (1965). The Logic of Collective Action. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Ormerod, E., & MacLeod, G. (2019). Beyond consensus and conflict in housing governance: Returning to the local state. Planning Theory, 18(3), 319–338. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26759191

Patel, Shirish B., Alpa Sheth, & Neha Panchal. (2007). Urban Layouts, Densities and the Quality of Urban Life. Economic and Political Weekly, 42(26), 2725–2736. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4419764

Philifert, P. (2014). Morocco 2011/2012: Persistence of Past Urban Policies or a New Historical Sequence for Urban Action? Built Environment (1978-), 40(1), 72–84. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43296872

Pløger, J. (2004). Strife: Urban planning and agonism. Planning Theory 3(1): 71–92.

Preville, P. (2011). Exodus to the ‘burbs: why diehard downtowners are giving up on the city. Toronto Life September 14. (Accessed January 29, 2014: ttp://www.torontolife.com/informer/features/2011/09/14/exodus-to-the-burbs-whydiehard-downtowners-are-giving-up-on-the-city/)

Priemus, H., & HALL, P. (2004). Multifunctional Urban Planning of Mega-City-Regions. Built Environment (1978-), 30(4), 338–349. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24026086

Rancière, J. (1999). Dis-Agreement: Politics and Philosophy. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

Randall, T. A., & Baetz, B. W. (2015). A GIS-based land-use diversity index model to measure the degree of suburban sprawl. Area, 47(4), 360–375. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24811684

Raynor, K., Matthews, T., & Mayere, S. (2017). Shaping urban consolidation debates: Social representations in Brisbane newspaper media. Urban Studies, 54(6), 1519–1536. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26151428

Raynor, K., Mayere, S., & Matthews, T. (2018). Do ‘city shapers’ really support urban consolidation? The case of Brisbane, Australia. Urban Studies, 55(5), 1056–1075. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26428476

Rousseau, J. J. (1978). On the Social Contract: With Geneva Manuscript and Political Economy. New York: St Martin’s Press.

Ruming, K. and Houston D. (2013). Enacting planning borders: Consolidation and resistance in Ku-ring-gai, Sydney. Australian Planner 50(2):123–129.

Ruming, K., Houston D. and Amati M (2011). Multiple suburban publics: Rethinking community opposition to consolidation in Sydney. Geographical Research 50(4): 421–435.

Sager, T. (2018). Planning by intentional communities: An understudied form of activist planning. Planning Theory, 17(4), 449–471. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26539550

Scheurer, J., Curtis, C., & McLeod, S. (2017). Spatial accessibility of public transport in Australian cities: Does it relieve or entrench social and economic inequality? Journal of Transport and Land Use, 10(1), 911–930. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26211762

Searle G and Filion P (2011) Planning context and urban intensification outcomes: Sydney versus Toronto. Urban Studies, 48: 1419–1438.

Sewell, J. (2009). Shape of the Suburbs: Understanding Toronto’s Sprawl. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Shasore, N. E. (2018). ‘A Stammering Bundle of Welsh Idealism’: Arthur Trystan Edwards and Principles of Civic Design in Interwar Britain. Architectural History, 61, 175–203. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26794867

Stretton, H. (1971). Ideas for Australian Cities. Melbourne: Georgian.

Stone, B., and M. O. Rodgers, 2001: Urban form and thermal efficiency—How the design of cities influences the urban heat island effect. Journal of American Planning Association, 67, 186–198.

Swyngedouw, E. (2009). The antinomies of the postpolitical city: In search of a democratic politics of environmental production. International Journal of Urban and Regional Studies 33: 601–620.

Swyngedouw, E. (2011). Interrogating post-democratization: Reclaiming egalitarian political spaces. Political Geography 30: 370–380.

Tapper, N. J., 1984: Prediction of the downward flux of atmospheric radiation in a polluted urban environment. Australian. Meteorological Magazine, 32, 83–93.

Troy, L. (2018). The politics of urban renewal in Sydney’s residential apartment market. Urban Studies, 55(6), 1329–1345. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26510366

Viljoen, A., Schlesinger, J., Bohn, K. & Drescher, A. (2015). Agriculture in urban planning and spatial design. In: de Zeeuw, H. & Drechsel, P. (eds.) Cities and agriculture. Developing resilient urban food system, pp. 88-120. New York, Routledge.

Wood, G., Berry, M., Taylor, E., & Nygaard, C. (2008). Community Mix, Affordable Housing and Metropolitan Planning Strategy in Melbourne. Built Environment (1978-), 34(3), 273–290. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23289784

Wright, K. (2010). The Relationship Between House Density and Built-Form Energy Use. Environment Design Guide, 1–8. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26150782

Yule, P. (ed.) (2004). Carlton: A History, Melbourne University Press.

*****

We, of the Southern Brisbane Suburban Forum Inc., submit this report as a submission to the Queensland Government and Council as being truthful and accurate.

Yours sincerely

Dr Neville Buch

President, Southern Brisbane Suburban Forum Inc.

Acknowledgement of the editing and textual contributions of SBSF’s urban engineer Elizabeth Harrison, and Dr.

Adrian O’Connor, South-East Queensland geographer, and Dr. Neil Peach, urban sociologist.

Public Historian and Sociologist,

MPHA (Qld), Ph.D. (History) UQ., Grad. Dip. Arts (Philosophy) Melb., Grad. Dip. (Education) UQ.

ABN 86703686642

[1] Ian Nairn (1930-1983) was the British architectural critic who coined the word ‘Subtopia’ to indicate drab suburbs that look identical through unimaginative town-planning. There is an intellectual link here with the ABC television program “Utopia”.

[2] J. Gordon and C. Gordon (1933). The London Roundabout. Edinburgh: Harrap.

[3] Lewis Mumford (1895-1990) is the best urban sociologist to go, to understand the big problems of urban-town-city planning currently in Queensland.

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- Dear grossly, ethically, corrupted - December 21, 2024

- Thoughts with a Professional History colleague on “Artificial Intelligence” - December 21, 2024

- Stephanie M. Lee on “AI by omission”, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Thursday, December 19, 2024 - December 20, 2024

From Dr Neil Peach: The current SEQ Regional Plan is Shaping SEQ 2017, see https://dsdmipprd.blob.core.windows.net/general/shapingseq.pdf

From Dr Neil Peach: There are multiple reasons for not approving this request [even if it is simply on the grounds of waiting for a more apposite time to fully consider the merits of such a proposal]. Some pertinent justifications for not approving the permit, without entering into the pros and cons of the proposal are as follows. It would be inappropriate to approve this request from BCC prior to the resolution of the SEQ Regional Plan and the consideration of feedback that flows from that process. There is no need to approve this proposal at this stage because it… Read more »