The History and Future of Apologetics Courses in Christian colleges: The Historiographical Challenges from Marc Bloch (1886-1944).

By Neville Buch, Ph.D., MPHA

2023 PESA Conference

INTRODUCTION

The paper is an examination on the history and future of apologetics courses in Christian colleges, with an argument that such courses are either collapsing or being redesigned, but that the better educational philosophy would be in the teaching of reasons for faith — that is, such ‘apologetic’ sources — be returned back into the larger disciplinary and open discourses of history, sociology, philosophy, and theology proper. In 1981 Vernon Bates put forth the argument that “… Christian apologetics are treated as legitimating formulas designed to ward off threats to one’s universe.” Forty years later, the truth of the formulation-type mindset, and its demise, is apparent with an article from The Washington Post on the new American house speaker, Mike Johnson’s, plan to establish a Christian law school (Kranish and Stanley-Becker 2023). Johnson had begun a feasibility study for a Christian Law School in 2010. It would have been known as Louisiana Christian University, and its parent school was Louisiana College, a private Southern Baptist college in Pineville. It is claimed that $5 million to buy and renovate the project headquarters, among other expenses.

The feasibility study was said to be a “hodgepodge collection of papers.” This is what American evangelical apologetics looks like: high on talk of American enterprise, low on the education and application of intellectual history and sociology. The scheme’s failure was inevitable when you compare the evangelical apologetic planning to the well-established history of Law School of Catholic Universities. Schools of Catholic apologetics do exists but Catholic academia keeps such schools at great distance to the traditional schools of the humanities and social science, and particularly including Law. Apologetics is different to doing legal defence cases, for the very reason that worldviews of belief involve judgements which is not weighted on the Law. This is the Kantian tradition (Kant 1790) which has kept scholarly Protestant worldviews continuing in the times of hype-modernism and postmodernism. Kant talked about moral law but introduced a new transcendentalism, different to Plato. Moral law were metaphysical principles, but application would always be skewed in practical reason. The Dutch Reformed tradition, to which American evangelical scholarship, is largely based, was marginally influenced from Kant’s schema, but placed heavier reliance in the concept of God’s law. From the mid-century, there has been no consensus in American evangelical scholarship, between the model of Immanuel Kant, a pietist, and the model of Abraham Kuyper, a neo-Calvinist. In politics, the former separated most clearly the roles of Church and State, and for the pietist communities they were not of the world. The Calvinist model had always separated roles, but Calvinism privileges the Church above the State in the formal, establishment, roles. The pietist acts out privilege in folky separatism, which connects pietism to political radicalism.

Schooling and Apologetics

In considering apologetics, there are various schools of religious thought, Modernism, Neo-orthodoxy, Neo-evangelicism, Evangelicism, and Fundamentalism, are as examples of attempts to develop “viable apologetics or legitimating formulas” (Bates 1981). This is the same argument of Buch’s American Revivalist Tradition (ART) thesis (1995). Frameworks in Christian philosophy of education is critically considered, and the ART way of thinking is not only contained within the boundaries of the United States. The author’s doctorate (Buch 1995) has demonstrated that that the way of thinking has been present in Australasia for more than half-century, and American schools of evangelicalism are well-established in Australia and New Zealand, and Papua New Guinea, and Polynesia.

21st Century Criticism of Apologetics

Although there is a current re-think on Christian Apologetics for the 21st Century (Sudduth 2003, Penner 2013, Siniscalchi 2013, Stackhouse 2014, Smith 2023), much of the thinking still pertains to the early 20th century debates and outlooks. For the past decade “The End of Apologetics” has been herald among evangelical communities (Penner 2013; Siniscalchi 2018). The end is conveyed as the continuation of “Christian Witness”, pietistic opportunity for personal testimony, avoiding what is perceived as the intellectual pitfalls of apologetics. Ted A. Smith (2023) denotes the wider context as “The End of Theological Education,” which comes as the phoenix fire and resurrection. Smith is speaking in a different context in the decline of theological enrolments, but it illustrates the difference between theology as a knowledge discipline and college-level apologetics courses. Apologetics is a technology of rhetorical defence; it does not have the comprehensive examinations that a Batchelor of Theology course is expected to have. Smith’s problem with the decline of theological education is that a majority of potential enrolments would be happier with a lighter apologetics and ministry program than the rigours of theology, or a studies-in-religion, degree.

Part of the problem is confusion about the role of the Reformed Tradition and negative or positive apologetics, to which Michael Sudduth (2003: 299–321) had untangled. According to Sudduth, Reformed epistemologists have criticisms of both particular versions of natural theology and positive apologetics “that can constructively shape future approaches to the apologetic employment of natural theology and Christian evidence.” However, Sudduth’s argument is merely about which is the sharpest tool in the shed, and how to use it. The big picture on Christian worldview is lost in such an argument. In the meantime, John Stackhouse Jr. (2014) has taken the American Neo-Evangelical Tradition further into the sphere of existentialism, and following the pietists, Christian Epistemology becomes a matter of articulating the believer’s passionate and personal vocation; as in Luther’s Here I Stand. What is too overlooked by Stackhouse and the evangelical apologists who follow his approach, is the disjunction between existential mindset and the concept of apologetics. The existential character is the person who does not defend herself or his self. The person simply chooses, and the rationality of existentialism is the legitimacy to make such a decision. The only sociology for existentialism is to affirm, for everyone, the capacity of such freedom, or slavery or alienation in not making clear choices to live, in the absurdity or not. If it has positive apologetic characteristics, then existentialism is an affirmation for living in one constructed meaning.

SEE FULL PAPER: 2023 PESA Paper. Bloch, Philosophy of Education, and Apologetics

The Ongoing Conclusion: The Educated Society

On this basis, the College courses of Christian college do more harm than good. There are several defuncted (dysfunctional) characteristics of apologetics teaching.

- Imagining an Education Society

In different ways – nationalism (Richardson 2002), understanding marginality and outliers (Greenleaf, Hinchman 2009; Hughes, Miller, Karls 2022), and multiliteracies (Jacobs 2013; Rhodes, Alexander 2014) – apologetics misses what it is to imagine an Education Society.

- Spiritual Leadership

Apologetics teaching prides itself on its spiritual leadership, but too frequently it misses the “Critical and Spiritual Engagement” of “Transformative Instructional Leadership” (Dantley 2011).

- Thinking for Peace

Apologetics teaching is almost completely unaware of the historiographical failure, in its leaning into culture-history rhetoric (Buch 2021).

- Language

Those who perform apologetics teaching would like to think it goes to the reframing rhetoric of fear with narratives of agency and hope (Caraballo, Martinez 2019). Apologetics, however, is grounded necessarily in the defensive posture of defence, and this is the reason why it struggles in leveraging Language.

- Politics and Policy

Finally, too often, those on the ground are too resistant to messages of Globalization and Transnationalism (Lauria, Mirón 2005). Those at the top, the decision-makers, are sensitive to that groundswell of resistance. It is for this reason that poorly understood or harmful educational policies are difficult to change across the levels of governances.

*****

FOR FULL PAPER:

2023 PESA Paper. Bloch, Philosophy of Education, and Apologetics

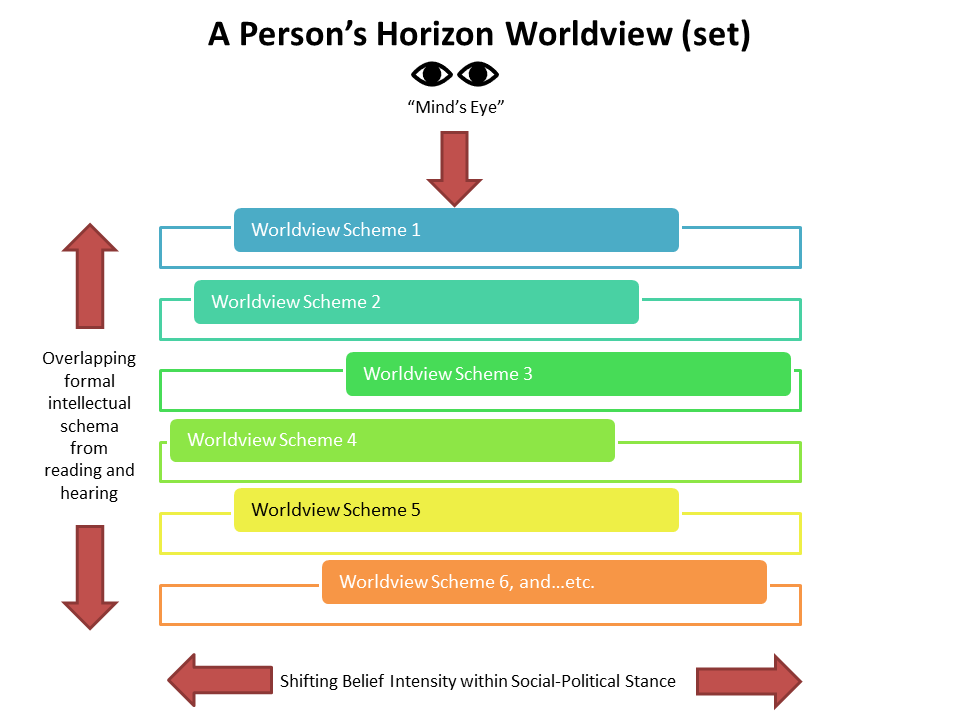

Featured Image: Mind’s Eye of a Personal Horizon Worldview

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- Dear grossly, ethically, corrupted - December 21, 2024

- Thoughts with a Professional History colleague on “Artificial Intelligence” - December 21, 2024

- Stephanie M. Lee on “AI by omission”, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Thursday, December 19, 2024 - December 20, 2024