© EHA Inc. and Dr Neville Buch

For the 2023 Evangelical History Association (EHA) Conference, “Telling Our Story”, Alphacrucis College, 30 Cowper St, Parramatta NSW, Australia. 10.45-11.15. a.m. Saturday 20 May, 2023, Alphacrucis College, 30 Cowper St, Parramatta NSW, Australia.

This is the presentation handout version which is not the abbreviated 20 minutes speaking presentation, nor the full paper. Please refer to the forthcoming EHA Lucas journal edited publication.

FULLER VIEW FOR TELLING THE STORY OF AUSTRALIAN EVANGELICAL HISTORY

By Dr Neville Buch, MPHA (Qld), EHA, AHA.

“During the 1940s, Fuller Seminary joined Westminster as a professional school dedicated not only to the preparation of ministers but also to the prosecution of research.”

Mark A. Noll (1994). The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, Grand Rapids: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company page 219.

“…if this school is to be, it should be the best of its kind in the world. It should stand out first, as being absolutely true to the fundamentals of the faith and second, as a school of high scholarship…particularly the study of the atoning work of Christ.”

Charles Fuller writing to Wilbur Smith in 1946, cited in Mark Hutchinson and John Wolffe (2012). A Short History of Global Evangelicalism, New York: Cambridge University Press, page 191.

To start, allow me to paint a small story of my recent sojourn to the United States. It was the 31st of January (the next day for AEST; 1st of February 2023), on a cool but sunny morning. I was preparing in the hotel lounge, Palihotel Westwood Village, for the afternoon with the Dean for the School of Theology and Mission at Fuller, Dr. Amos Yong, and Dr. Kirsten Kim, the Paul E. Pierson Chair in World Christianity and Associate Dean of the Center for Missiological Research (for the sweep of the history on Fuller T.S., Fundamentalism, and Neo-Evangelicalism, see Marsden 1980, 1987).

The journey from Westwood to Pasadena gave me sufficient time. In the hour-long drive there, to look around. I walked around and through the famous City Hall and had lunch at the California Pizza Kitchen. The journey along the San Diego and Ventura freeways blew my mind in the landscapes which seem to swallow you up. The wide roads and freeways provide the sense of space, as well as the flatness; and yet there are so many twist and turns through the hills while remaining at the same height. Much concrete and steel, and yet the many, many, palm trees and the hills, seem to give life to the urban machine. Freeways appear like a mass of arteries. And there is much clogging, as well as the racing heart.

My uber driver, the darker-skinned George, gave me a glorious tour which for him was a charge into the normal scene. And I guess it is the stranger who is taken by the unfamiliar, and understand the freedom of foreign travel. After lunch and before the Fuller meeting, I walked up to the place where 30 years ago, Ruth and I stared at the San Gabriel mountains. It is a gigantic presence pressing against the Pasadena landscape on the Foothills Freeway. Unfortunately, my photographs do not do the visual sensation the justice it deserves. You have to be here to see it. Fuller has always welcomed me, and since the last time that I sojourned to the halls of learning in Pasadena thirty years ago.

Nothing clearly prepared me for my discussion Drs. Yong and Kim that day than a few recent publications on race and evangelicalism, most formatively Jesse Curtis’s The Myth of Colorblind Christians: Evangelicals and White Supremacy in the Civil Rights Era. Still, I was almost thrown off my chair in the Dean’s conference room when Dr. Yong spoke of “white backlash” among the American evangelical congregations, and whose parents were reluctant to send their children to Fuller. It is obvious that the situation is delicate in Pasadena. Fuller was concerned there were the declining enrolments, and general discussion puts a primary reason down, not to the exploration of political theologies which Yong had published from the 2009 Cadbury Lectures, but from Yong’s prioritisation to Asian-American thinking, beginning with the launching of the Korean Studies program with courses offered in the Korean language, in 1992. Something significant had changed at Fuller and it impacted in the Fuller View of Australian Evangelical History. Things had changed since my last visit to Pasadena in December 1991 and January 1992. I had been researching across the whole length of the United States for my Buch’s ART thesis, published as the doctorate in 1995. ART stands for the American Revivalist Tradition. I recall in those cooler evenings of January 1992, Ruth and I fellowshipping with the Australian Sociologist, Robert Banks and his first wife, Julie. Both Ruth and Julie were to pass with a brain tumour.

At the time, Robert Banks represented at Fuller the very opposite of Americanised Church Growth thinking. In the late 1980s and early 1990s Banks led an Australian ex-pat group of Fuller students at Pasadena. Of all evangelicals in Australia of his generation, Banks enjoyed the most stimulating career. Banks was a graduate of Moore Theological College (1959-1962), and he completed a Master of Theology at King’s College in the University of London and a Ph.D. in New Testament on Jesus’ attitude to the Law at Clare College Cambridge University. In 1969, he was appointed as a Research Fellow in the History of Ideas Unit at the Australian National University, and in 1974 he became Senior Lecturer in Ancient History at Macquarie University, Sydney. From his ideas of ancient Christian community, he created and led home-based congregations in several Australian cities. In 1989 he was invited to become Foundation Professor in The Ministry of the Laity at Fuller where he introduced a Master of Arts in Christian Leadership for lay people and a Doctorate in Practical Theology. In early 1999 he returned to Australia, and subsequently became the first Director and Dean of the Christian Studies Institute at Macquarie University.

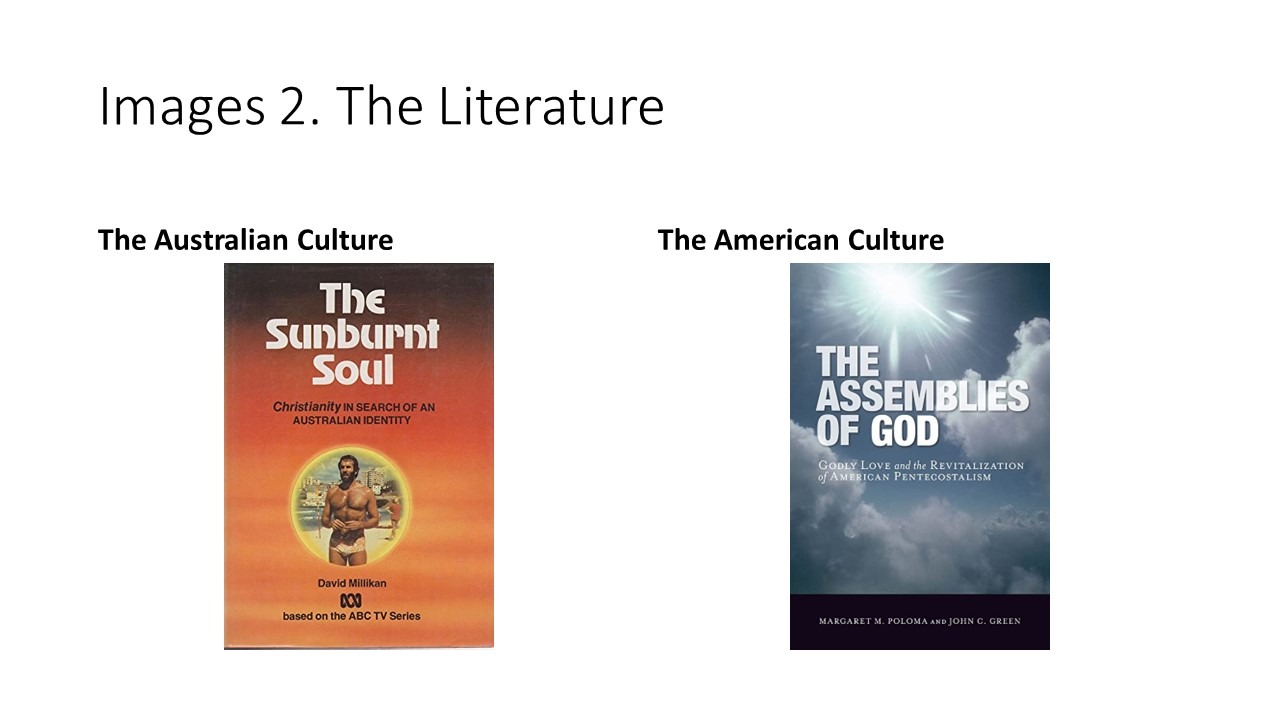

In the early 1980s Banks had been part of the short lived ‘gum-leaf’ theology which crystalised around David Millikan’s The Sunburnt Soul: Christianity in search of an Australian identity, which was a 1981 ABC-TV series as well as a coffee-table book for a broad audience (see also Millikan et al 1982). At the time, the average Australian Protestant leaders did not see American models of church life as cultural products. If they did, there had been a general belief that models of church life could be divorced from cultural characteristics, and be Australianised. How this would occur was never thought out, except for the short-lived experiment in Gum-Leaf Theology of the early 1980s.

Banks’ home-based churches was given a space at Fuller as advocacy for the Australian innovation in the School of Theology, which contrasted sharply with the Church Growth model of McGavran and his Fuller teachers. There were other examples of the alleged ‘Australianist’ innovation: Charles Ringma’s counter-culture Teen Challenge Inc. (Queensland founded), Athol Gill’s House of Freedom (Brisbane), and the House of the Gentle Bunyip (Melbourne), John Hirst’s House of the New World (Sydney), and David Andrew’s Waiters Union (Brisbane). It is difficult to argue what the Australian characteristics were. In many cases, American patterns of innovations were involved. Ringma had bought over the initial model from agreements with Don Wilkerson in Philadelphia (Founder Dave Wilkerson’s brother and business partner). John Hirst and Athol Gill were inspired by the ‘Jesus Revolution’ movement which had been developing in California since 1967 (Enroth et al 1972). Dave Andrew was a Fuller student. Nevertheless, the characteristics of Bank’s, Ringma’s, Gill’s (Hirst’s to a lesser extent), and Andrew’s, counter-culture, muted any clear American characteristics for the Australian scene. Nationalistic analysis is a mistake if it parks the thinking too conveniently.

What my Fuller paper offers today is a contemporaneous history. Amos Yong himself, though, does not fully align with the Buch 1995 ART thesis, but there is sufficient alignment with the general arguments on cultural Americanisation and also with Yong’s concerns on the Evangelical meltdown over ethnicity, race, and politics. The ideological work of Yong is extraordinary and I fear is underread in the pews.

Yong’s argument is that the Korean Church Growth movement is evidence of global convergence rather than my ART argument. The Korean Church Growth movement assisted the rise of the Asian-American movement in the United States, in the same way that it is alleged that the Australian Hillsong movement boomerang back to the United States ideas and practices of Church Growth. My counterpoint here is that the origins in these movements were originally from American missionaries and the American Evangelical Leadership, considering the larger scoping of the histories. Before Hillsong, there were the Church Growth movements in Australia from Reginald Klimionok’s Assemblies of God movement and the movement of Trevor Chandler’s Christian Life Centre (CLC) and Clark Taylor’s Christian Outreach Centre (COC). These were developed in the Queensland, but in the latter case of Chandler (CLC) and Clark (COC) there was a passage of the Latter Rain movement, originating in the United States and transferring (largely) to New Zealand before arriving in Australia. Frank and Brian Houston’s Hillsong movement arose both from American connections and the legacy of the Australia CLC and COC movements. All were based in Americanised Church Growth theoretical development of the ‘Neo-Pentecost Megachurch’. Klimionok (1983) provided the clearest example of the Church Growth theory and practice. It has been quietly whispered in the Australian evangelical circles that Klimionok did not import an American model. This is based on Klimionok connections with the Korean Paul Yonggi Cho. However, the connections happened through Dr Holland London, President of California Graduate School of Theology, and Dr John Hurston, Vice-President of California Graduate School of Theology and Dean of Church Growth International. Sociologically, Paul Yonggi Cho presented a mixture of American and Korean worldviews, American materialism and Korean Taoism, held in total contradiction, or paradox logic yet to be demonstrated (Buch 1995: 372). The attempt to water-down the ART thesis in defence of the Australian Megachurch model, as separate to its American legacy, “does not hold water.”

It is conceded that origins might not carry much weight for some nuanced arguments, and that the development of theo-nationalist mythologies do have differences. However, that is the prime criticism of Buch ART thesis – of origin-ism, the position of the Americanised New Christian Right that origins are not only the beginning of an argument, but simply the whole argument, is greatly mistaken and historically-put nonsense. We see such arguments in the movements of American-style Creationism and American-style moralism (articulated in Morris 1984); in the abuse of the national histories as idealistic myths. The criticism of the ART criticism – criticism to the false legitimation in the actual belief and practice – is that it is the historiography which cannot deal with the idea of change in key doctrines. Religion paradigms always trip up in orthodoxy. ART is a ridiculous ideology in its poor attempt to revive a sociology which has been passed over and will not return.

For us Australians, in this ART problem, the solution is a Fuller View for telling our stories, but must be balanced in the critical filters of local, region, national, and global outlooks.

I will concluded by how the Fuller education and view could stand in relation to educational and sociological models for Australian institutions and local pastors. I should say that all the immediate simplistic and nonsense dismissals have been deal with in two other sections called, “The Global Evangelical Context 1958-1987”, and “Was Fuller influential in the thinking of Australian evangelical histories?” You will have to read the full papers for the counter-points. However, what are Australian institutions and local pastors missing out from the contemporaneous history of Fuller Theological Seminary, Pasadena, California? To be brief, here is my summary points from the full paper:

First, the only Australian distinctiveness has been David Millikan’s gum-leaf theology 1980-1987, and it suspiciously had looked like an Australian version of ART – the use of national mythology to revive life in the Australian churches. The difference was that the American model anchored in a return to the Puritan heritage, the original sociological vision on the later waves of revivalism which kept reshaping the national mythology in different directions (McLoughlin 1957, 1960, 1987). Australian history never had that Puritan beginning; only in the misguided imagination of the Reformed Church historiographers (Murray 1988; and with regard to more critical Koch 1975). Furthermore, even American historians had seen ART’s reference to the Puritan heritage as problematic: an evangelical historiographical product, which mythologised with the thin historical evidence.

Secondly, the School of World Mission – which became the School of Intercultural Studies in the year 2003 – and, globally, the cultural studies field as a whole, has been sloppy and expressing too-many shifts in the articulation for the exact nature of transformations expected inter-cultural. From a contemporary theological perspective, revivalistic expectations for any culture was not the transformation desired in formal (proper) theology. In this analysis, political theology came to the fore.

Thirdly, in the new century, the neo-conservative intelligentsia – whose cultural analysis had driven the rightist political movements – became more open on the topic of political theology. The discourses, however, were obscure, from any political side, since the phrasing of ‘political theology’ could be used accusatory or advocacy: each either accusing the other of a “political theology which transformed into a political religion” or simply advocating a ‘theology of politics’ (Borghesi: 24-5). Yong was astute enough to map the spectrum of political theology and discussed elements which would assist the future of Pentecostalism and Evangelical theology as a whole. It was correctly abstract, open, and comprehensive for evangelical pastors and congregants to ‘wake up’ to the rightist lie about “Woke Ideology”. The Evangelical centralist attempt to moderate Pat Robertson’s Moral Majority and Dominion Theology-Reconstructionism, and so forth (historical account: Straub 1986, 1988; Criticism: Du Mez 2020; its Fuller theological expression: Lindsell 1976), only gave life to the nonsense; and today we have Trumpism.

At the larger scoping of global politics, Fuller in Australia is not a matter of global convergence but a matter of cultural Americanisation which remains largely undigested in evangelical church life. The objections from the evangelical congregations tend to be the ignorance of the global scoping. Furthermore, the ART gets alleged legitimatisation in congregational life with an argument that that such beliefs and practices have motivations in basic evangelical education. Critical sociology and historiography, however, resisted the false justifications that come with the references of David Bebbington’s quadrilateral definition without the knowledge of political theology. This is why Amos Yong’s mapping of political theologies from the 2009 Cadbury Lectures is so important.

Thank you.

VERSIONS AND RESOURCES OF PRE-PUBLISHED LUCAS ARTICLE

Evangelical History Association (EHA)

Fuller view for Telling the Story of Australian Evangelical History (PRESENTATION HANDOUT)

Fuller view for Telling the Story of Australian Evangelical History (APPENDICIES ONLY)

2023 EHA IMAGE PRESENTATION.

2023 EHA Speaking Text (for Image Presentation)

REFERENCES

Bebbington, David W. (1989). Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s, London: Unwin Hyman.

Borghesi, Massimo (2021). Catholic Discordance: Neoconservatism vs. the Field Hospital Church of Pope Francis, Collegeville: Liturgical Press Academic

Buch, Neville (1995). American influence on Protestantism in Queensland since 1945. PhD Thesis, School of History, Philosophy, Religion, and Classics, The University of Queensland. (https://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view/UQ:189291)

Buch, Neville (2022). Evangelicals & Nation-Building: Radical and Transformational Criticism from Across Christian Traditions in Queensland History, 2022 EHA Conference (in press)

Curtis, Jesse (2021). The Myth of Colorblind Christians: Evangelicals and White Supremacy in the Civil Rights Era, New York University Press

Enroth, Ronald M and Edward E. Ericson, C. Breckinridge Peters. (1972). The Jesus People: Old-time Religion in the Age of Aquarius, Grand Rapids: Williams B. Eerdman Publishing Company.

Du Mez, Kristin Kobes (2020). Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation, New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation

Hollenweger, W.J. (1972). The Pentecostals: The Charismatic Movement in the Churches, Minneapolis: Augsburg Publishing House.

Hutchinson, Mark and John Wolffe, (2012). A Short History of Global Evangelicalism, New York: Cambridge University Press.

Klimionok, Reginald (1983). God sent His Angel, Mt. Gravatt: Vision Enterprises Publication.

Koch, John B. (1975) When Murray Meets the Mississippi: A Survey of Australian and American Contacts 1838-1974, Adelaide: Lutheran Publishing House.

McLoughlin, William G. (1957). Modern Revivalism: Charles Grandison Finney to Billy Graham, New York: Ronald Press.

McLoughlin, William G. (1960). Billy Graham: Revivalist in a Secular Age, New York. The Ronald Press Company.

McLoughlin, William G. (1987). Revivals, Awakenings and Reform: An Essay on Religion and Social Change in America 1607-1977, The University of Chicago Press.

Marsden, George M. (1980). Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth Century Evangelicalism 1870-1925, New York: Oxford University Press.

Marsden, George M. (1987). Reforming Fundamentalism: Fuller Seminary and the New Evangelicalism, Grand Rapids: William B. Eermanns Publishing Company.

Miller, Robert M. (1958) American Protestantism and Social Issues 1919 – 1939, Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press.

David Millikan (1981). The Sunburnt Soul: Christianity in search of an Australian identity, Homebush West: ANZEA Press.

Millikan, David and Douglas Hynd, Dorothy Harris, (Editors, 1982). The Shape of Belief: Christianity and Australia Today, Homebush, Victoria: Lancer. 1982.

Morris, Henry M. (1984). A History of Modern Creationism, San Diego: Master Books.

Murray, Iain H. (1988). Australian Christian Life From 1788: An Introduction and an Anthology, Edinburgh: The Banner of Truth Trust.

Lindsell, Harold (1976). The Battle for the Bible, Grand Rapids: Zondervan.

Niebuhr, H.Richard. (1937) The Kingdom of God in America, New York: Harper and Brothers.

Niebuhr, H.Richard. (1951). Christ and Culture, New York: Harper and Brothers Publishers.

Noll, Mark A. (1994). The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, Grand Rapids: William B. Eermans Publishing Company.

Yong, Amos (2005). The Spirit Poured Out on All Flesh: Pentecostalism and the Possibility of Global Theology, Grand Rapids: Baker Academic

Yong, Amos (2010). In the Days of Caesar: Pentecostalism and Political Theology, Grand Rapids: William B. Eermans Publishing Company

Yong, Amos (2014). The Future of Evangelical Theology: Soundings from the Asian American Diaspora, Downers Grove: IVP Academic.

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- J. D. Vance’s Insult to America is to Propagandize American Modernism - July 26, 2024

- Why both the two majority Australian political parties get it wrong, and why Australia is following the United States into ‘Higher Education’ idiocy - July 23, 2024

- Populist Nationalism Will Not Deliver; We have been Here Before, many times… - July 20, 2024