I lived in Melbourne for a decade. Coming from Brisbane, what struck me is the largeness of the diverse landscape. The foliage and species differed, as well as the contours, but diverse suburban landscapes were paralleled in Brisbane, at a different scale. You had a grander ‘intercity’ region which the streetscape reminded me of South Brisbane and Annerley, from Brunswick to Coburg, along the Sydney Road. It was not actually ‘intercity’. Carlton is intercity. However, its streetscapes are historically present today as dense town shop frontage with tight suburban blocks behind.

Toorak-Clayton Suburban Comparison

Image: Some suburbs have more well-established trees than others. (ABC News: Prianka Srinivasan). From Prianka Srinivasan and Hellena Souisa, “As backyards get smaller and trees are removed, urban heat islands could be making suburbs hotter,” ABC News Online, 11 November 2021.

Suburban analysis of Melbourne usually focuses on the growth corridor of the south-east. Melbourne northside often gets forgotten – the workingman’s paradise from the late nineteenth century. Our family lived on the northside in that decade, and always thought of it as a grander parallel to the Brisbane Southside. There is an outer northside where suburban estates got going in the bush from the 1970s. The family moved from North Coburg to ‘Regent’: an old leafy area of Reservoir off from High Street; it was a reminder of ‘Auchenflower’. It is certainly not ‘Toorak’ with the overhanging trees on the streetscape (as in the pictorial above). Nevertheless, we had moved not much further northward, more eastward, and we had found well grassed footpaths and well-kept gardens, as you do in that part of Melbourne.

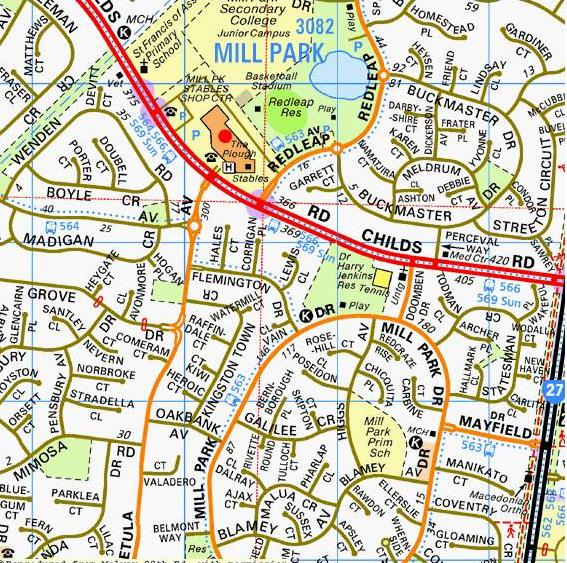

Image: Map of Mill Park. (Taken from my copy of Melways. Neville Buch. Melbourne Images Collection).

It has never been measured to my knowledge, but if you look at the maps and compare Melbourne and Brisbane, it seems that Brisbane, the river city, is much devoid of parklands along its watercourses in comparison to Melbourne. Brisbanites laugh at Melbourians over the size and flow of Yarra River. However, Melbourne has done extraordinary work over decades on the creeks which flow into the Yarra. The cultured Merri Creek landscape is world-class and far exceeds the work done on the Kedron Brook (let alone the larger work done on the less greener Oxley Creek). In the area we had moved to, there was the Coburg Lake Reserve, nearby westward next to Sydney Road, and also the Edwardes Lake Park nearby in the north. There is nothing to compare in Brisbane.

Image: 10 Rosehill Court Mill Park (large). (Neville Buch. Melbourne Images Collection).

Eventually, the family made a second move, out further onto the Melbourne’s north-east. This is one side of the outer ring of Melbourne, the equivalent of Algester and Parkinson on Brisbane Southside. It is marked by the large Bundoora Park, where Mount Cooper peaks. Most of Melbourne’s northside is a gentler rising slope to this peak, and the height as you enter Melbourne from the north (none of sharp rises of Brisbane’s riverhills). The north-east urban sprawl followed Plenty Road which parallels the Plenty Creek valley on one side, and where the Darebin Creek follows on the other side. There is Melbourne’s version of our Griffith University, La Trobe in Bundoora. The family had moved to Mill Park, a suburb just further north of Bundoora, and has the RMIT Bundoora campuses nearby. Mill Park marks the end of Melbourne, and is, in fact, part of the Whittlesea Council area, the town outside of Melbourne boundaries (Mill Park is still classified as a suburb of Melbourne). The part of Mill Park we lived in was a historic racecourse for training horses in the bushland. We lived in a cul-de-sac off Mill Park Drive, off the main road of Childs. The cyclic drive marked the old racecourse. The houses were lovely brickwork from the 1970s. Most of the houses had weathered well in the dry heat, but there were some issues of brickwork cracking. We had a beautiful large home in Mill Park (pictured above).

Image: Bundoora Homestead. (Neville Buch. Melbourne Images Collection).

Now, I tell this long story for three points on urban development in Melbourne and the Brisbane City Council intended rollout of its neighbourhood plan for the outer Brisbane Southside suburbs. The first is that the Melbourne north-east has had high-density building, mostly student accommodation. Compared to the Nathan-Salisbury area (in Brisbane), Melbourne’s north-east has worked-in such buildings in keeping with greener suburbs (even though it is a drier climate) and the surrounding bushlands. The risks have been that the suburbs are prone to bushfire, however, with the new and modern high-density buildings — although changing the view and feel of the main roads (Plenty Road, being a major tramline) — there is still a spaciousness to the region. It has not stopped the urban sprawl, nor stopped the quickly filling-in of the main road shop-industry frontage. Think Logan Road, and it is only one quarter as bad. Nevertheless, you have the quiet feel of the ‘inside area’ of the Salisbury suburb, but not of the terrifying area of Nathan’s Kessels Road. Although Sydney Road has problems, the development of High Street and Plenty Road on the outer suburbs, with still-existing tramways, provided much safer and less heavy traffic than Kessels Road. The controversial (in its day) Melbourne ring road had done the same job as Brisbane’s Southeast freeway, but with better results. The Brisbane-Ipswich By-Pass has yet to be as effective.

Image: Horse Ride At Lower Eltham Park. (Not a Real Estate Pitch, as it is in an old leafy Melbourne outer suburb. Neville Buch. Melbourne Images Collection).

The second point is that Melbourne suburbs always have had large parklands, and often with lakes or reservoirs. Mill Park has Redleap Reserve. It would be like if Coopers Plains had a lake with wild birdlife, instead of thin strip of swampland. Thirdly, Melbourne northside, inner and outer, has preserved their heritage sites of industry in quieter space. Over the decades there have been issues with active industrial sites in the middle of residential areas, however, the problems have become less since the decline of Australian manufacturing industry. Forwarding thinking economists have argued that upgrading cottage industries to moderate sizes, with lighter footprints on the landscape, would be a far better approach in urban planning.

Image: Yet Another Picnic At Yan Yen. (Neville Buch. Melbourne Images Collection).

From Prianka Srinivasan’s and Hellena Souisa’s ABC News piece, it is obvious that there are still major town planning problems, but what if we compare the array of Melbourne councils to that of the single and large Brisbane City Council?

Image: Buch’s At South Bank On The Yarra. (Note the Foliage on the North Bank. Neville Buch. Melbourne Images Collection).

The question is whether the Brisbane City Council will listen or be tied to invested interests of the same old-same old? I have been told by members of the Council that we should not compare Brisbane to Melbourne in the local histories and historiographies. I say, la accuse, such responses are parochial stupidity, and should not be accepted by the neighbourhood!

Neville Buch, MPHA (Qld).

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- Dear grossly, ethically, corrupted - December 21, 2024

- Thoughts with a Professional History colleague on “Artificial Intelligence” - December 21, 2024

- Stephanie M. Lee on “AI by omission”, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Thursday, December 19, 2024 - December 20, 2024