by Neville Buch | Nov 4, 2022

The Cultural Influence of the 1970s Mainstream Evangelical Conservatism

In the previous essays the organisational history of Teen Challenge Inc. has been described under the activities and intellectual headings of ‘evangelical outreach,’ ‘Christian community’, and ‘social work’ with both secular and sacred regard for the person.

Organisational Teen Challenge Inc. workers across the timelines represented the thinking, collectively, of the triangular thinking of the mission, commune valuing, and working for a better, improved, or transformed society.

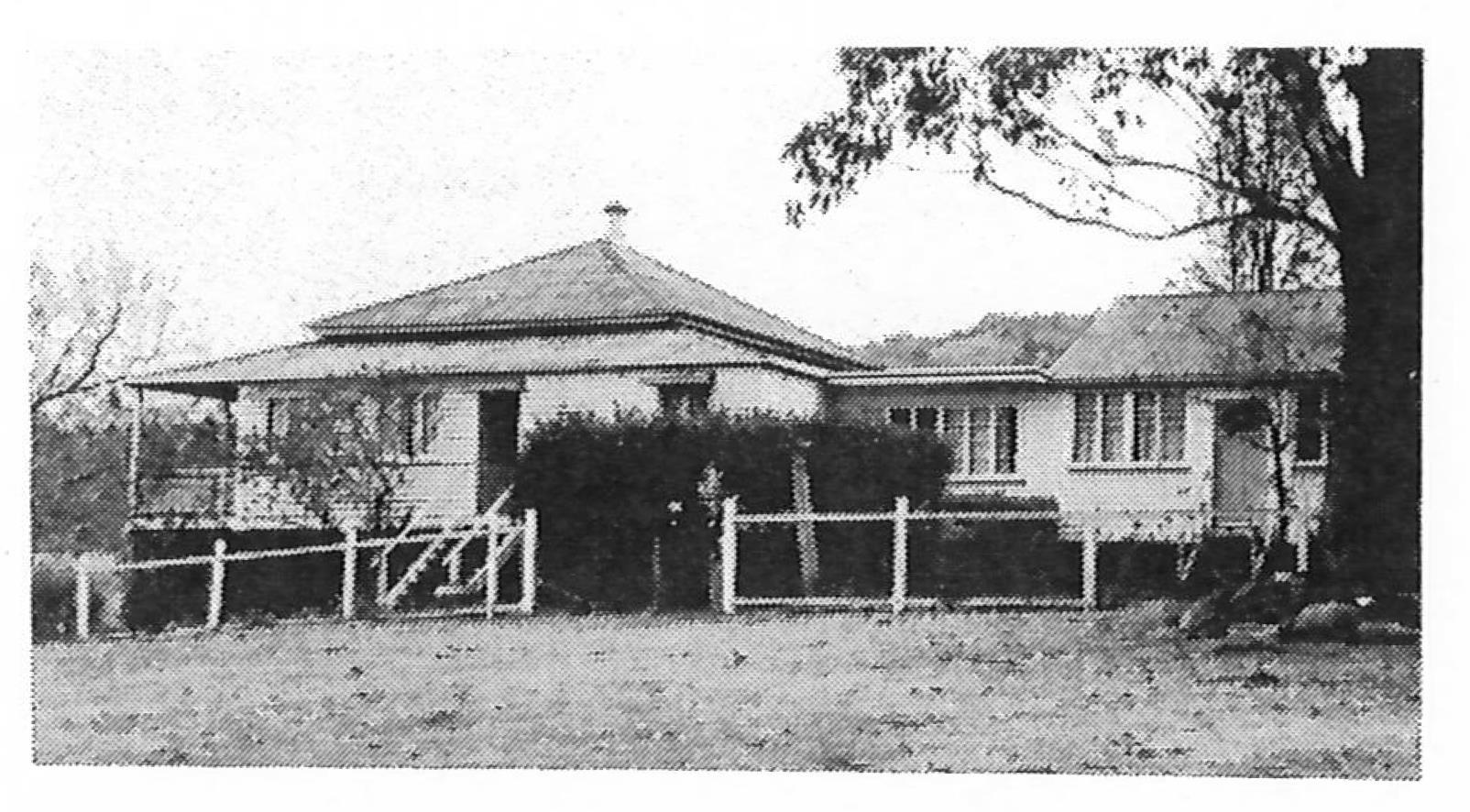

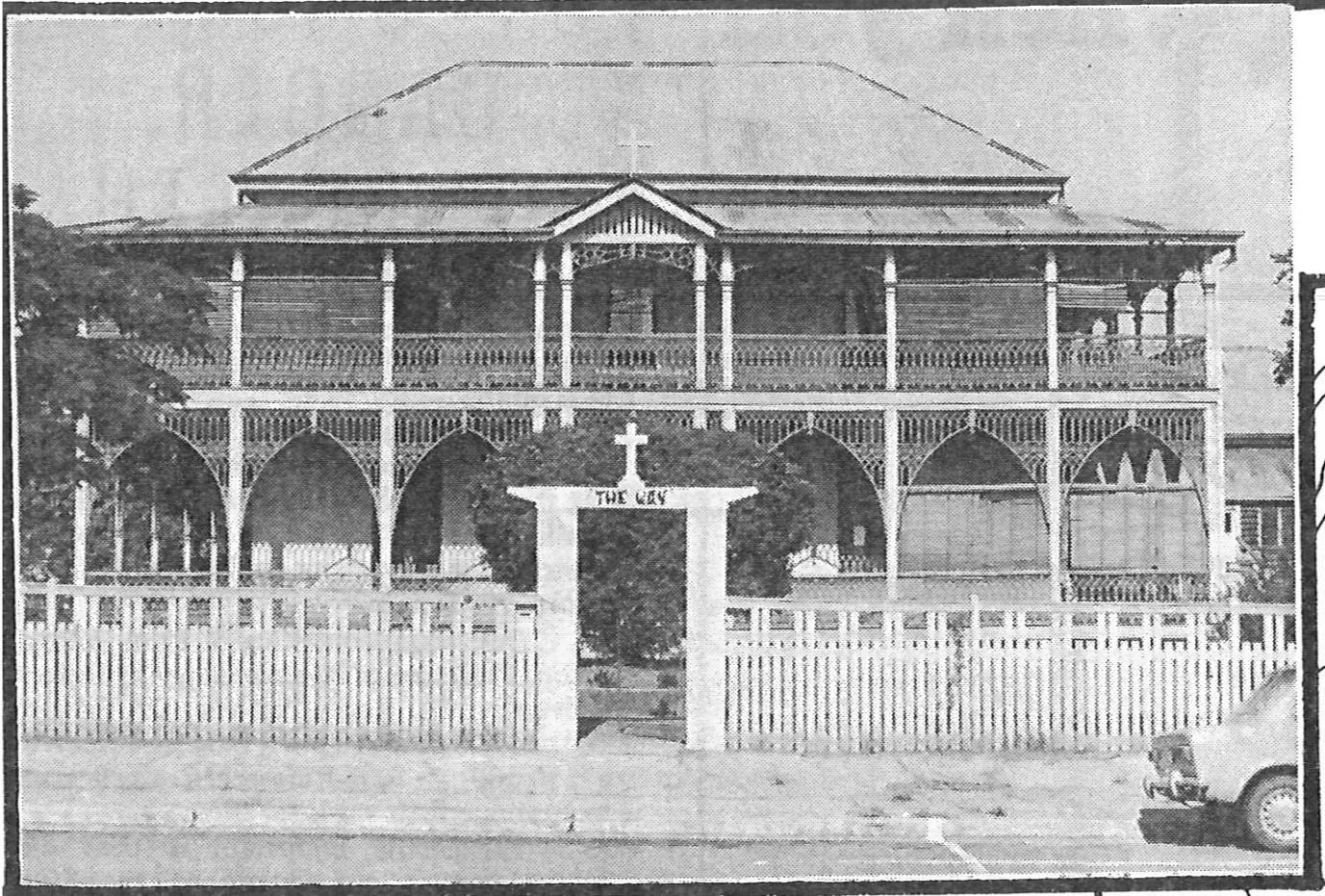

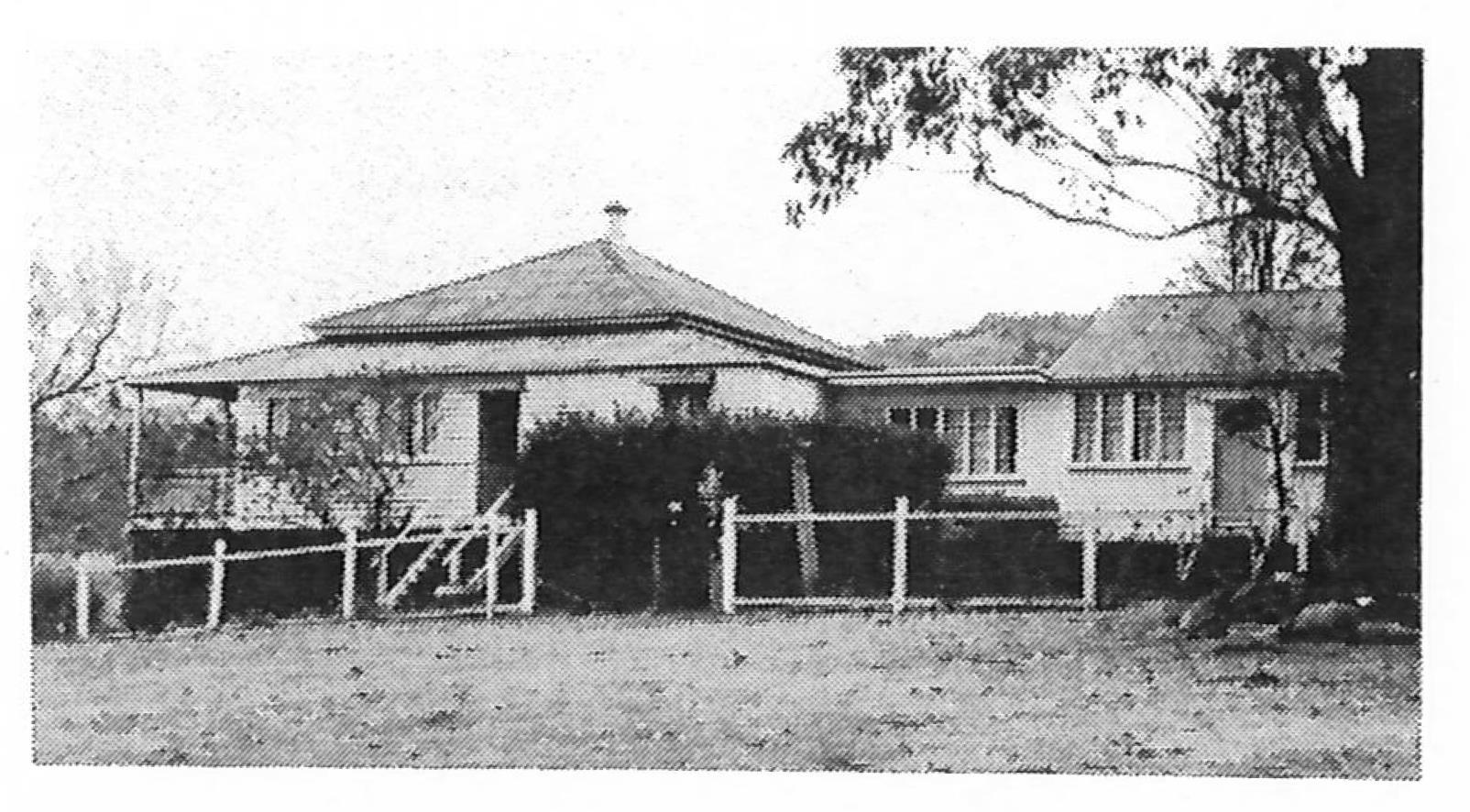

Figure 1. Teen Challenge Inc., Enoggera Terrace, Red Hill. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

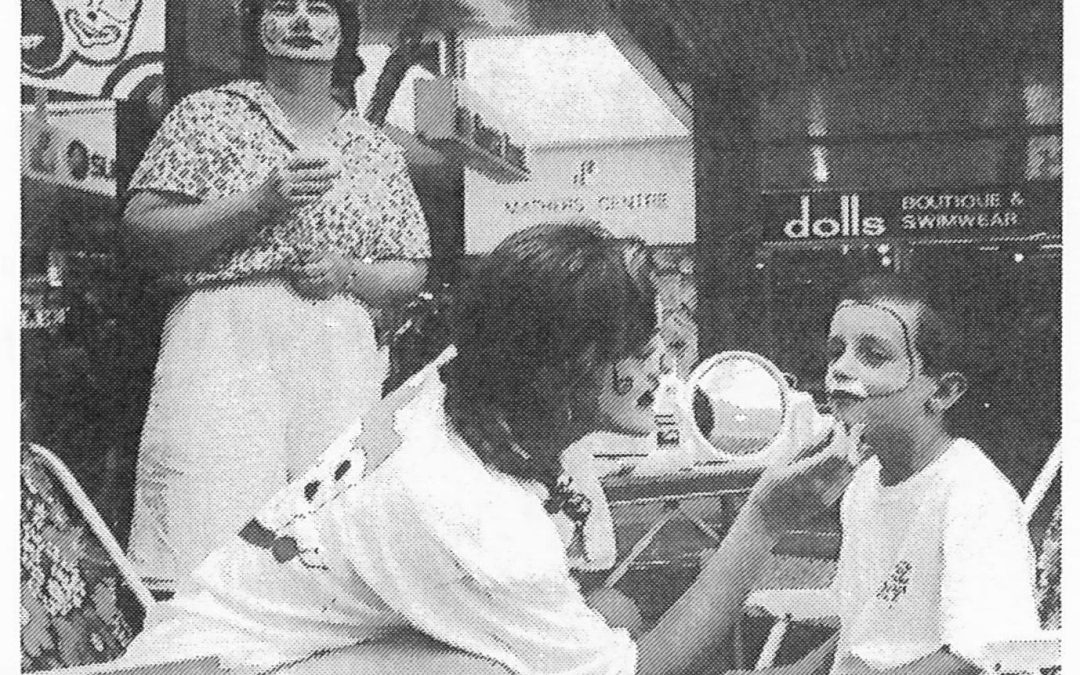

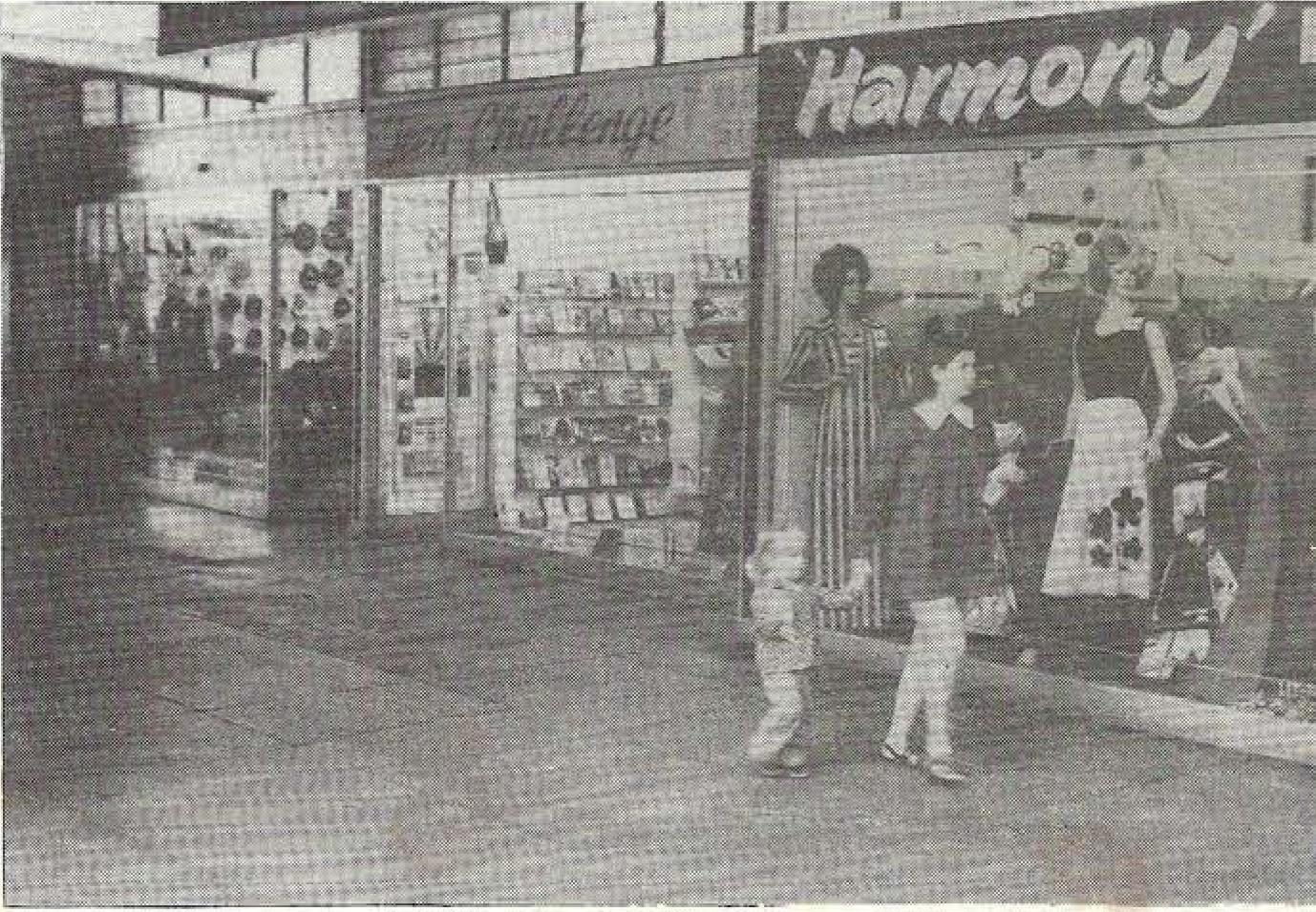

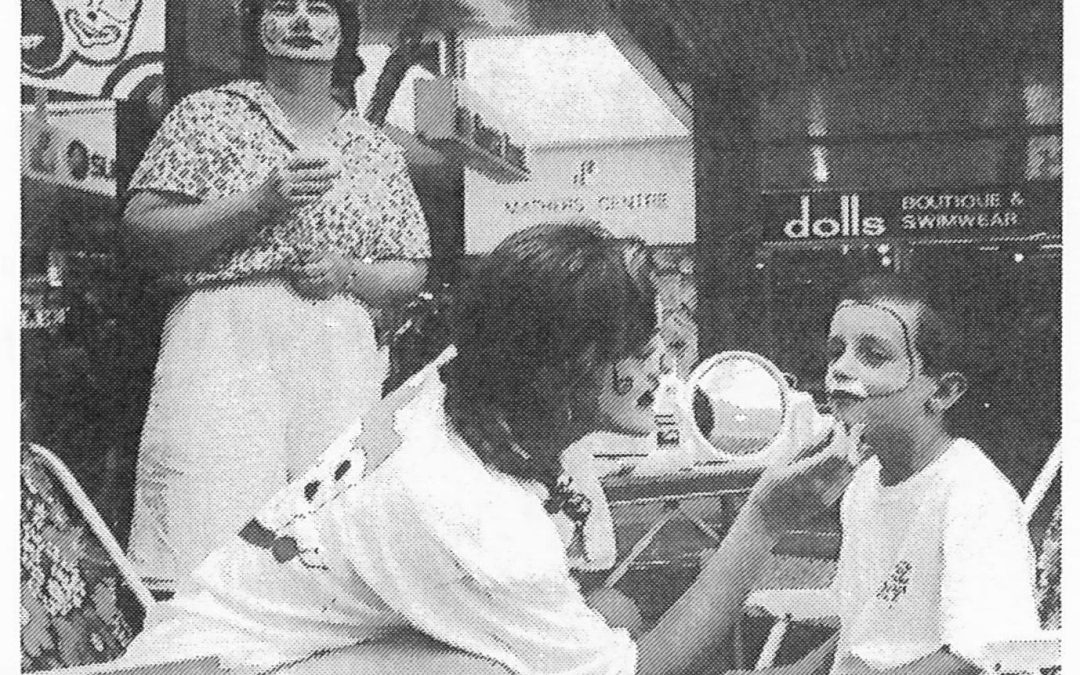

To take a snapshot of the early days of the Teen Challenge Inc. Office, from circa 1975 to 1984, at the Woolworths Shopping Centre, 107 Latrobe Terrace, Paddington (QLD 4064). It was a centre-point in time, coming from a location usually describe in the earliest years (circa 1974-1975) as located at Enoggera Terrace, Red Hill (QLD 4059). It would have been the third ‘Head Office’ following Newmarket and South Brisbane and combined with the Rehabilitation Home at the same address. The confusion of locations might be simply a matter of suburban boundaries, but there is more at play. There is a time shift here, and there is the common geographic confusion for common office workers, possibly stuck at their desks much of the time, and/or lacking good knowledge of their surroundings. The previous office site, up to circa 1975, was Newmarket ‘around the corner’ from ‘Enoggera Terrace’ in Enoggera Road (Confusing?). One of the hardest lessons for Christian missions is understanding landscape and understanding persons in landscape. Memory is not good enough to interpret the past and testimonies need further examinations.

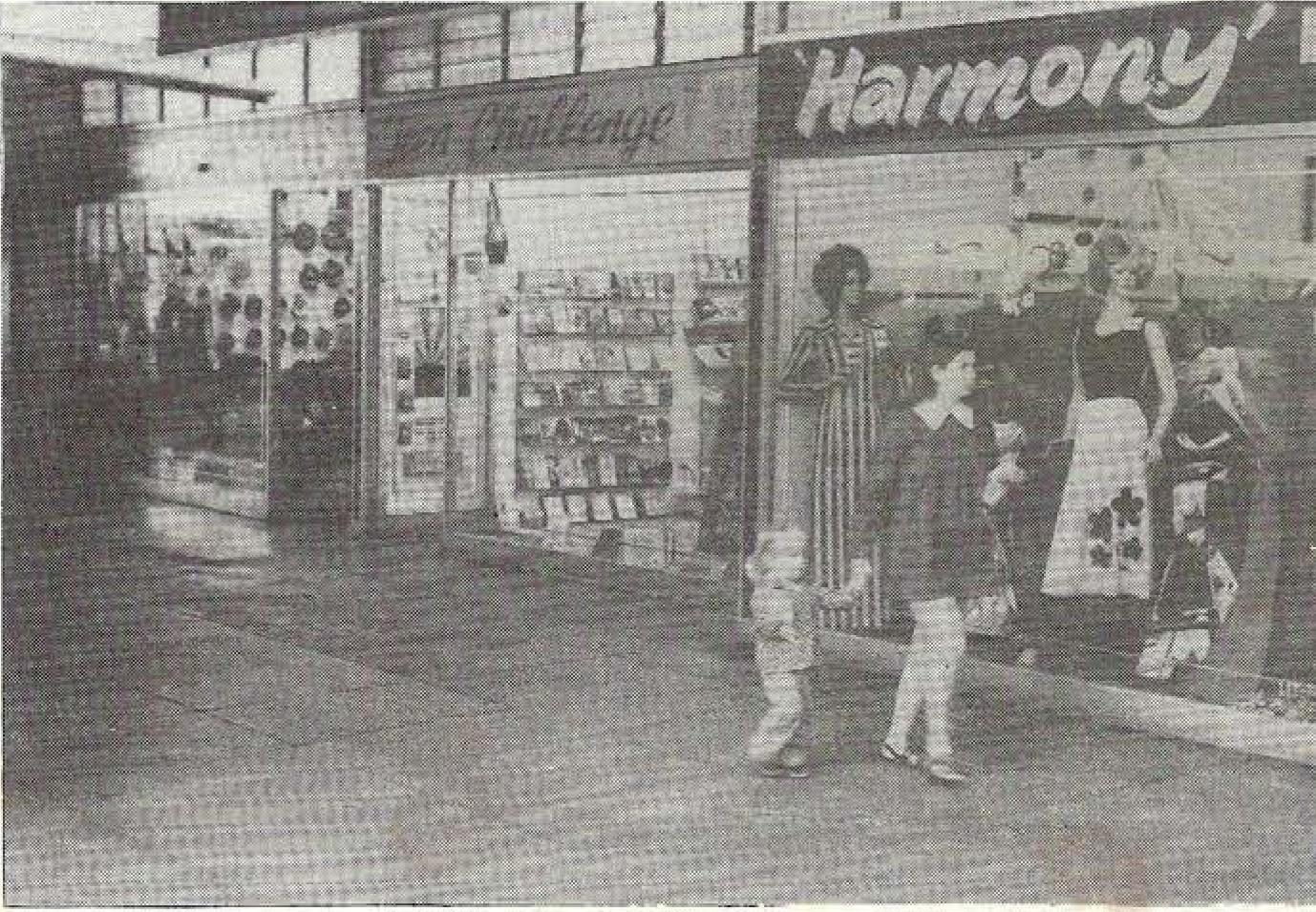

Figure 2. The Teen Challenge Bookshop, Newmarket. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

With Charles and Rita Ringma, mission is a driving force among the office workers. The Office was run in these days by John and Pat Healey, who came to Teen Challenge Inc. as workers of Youth With A Mission (YWAM). YWAM had a much stronger ethos of discipleship and evangelism than many other of the similar organisations in Brisbane. Among the YWAM literature there was a revivalist crusade theme, lacking a certain critical edge in the far more socially conscious Teen Challenge Inc. There were other early Teen Challenge workers who shared the same rough street preacher approach.

Figure 3. The Early Teen Challenge Inc. Office. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The Organisational Issues of Financial Philosophy and Strategy

However, Teen Challenge Inc. was a business from day one. The fourth area of the organisation was financial philosophy and strategy to keep the business running,

Much of that work was the role of the Board of Management, and, in the early days, Board members needed to have a more hands-on approach in the Office. Henry Baskerville was the first Treasurer, for the Board of Management, Teen Challenge Inc. He was the finance man with one foot in sacred space and the other in the space for secular operations. He was the Manager at the Newmarket Commonwealth Bank, and also Vice President for Gideons in Queensland. Next came Albert Hall who formally took up the title of the Office Administrator, working closely with Charles Ringma as the Executive Director. Albert Hall was also a Board member and with his secular work connections, the Board in those days met at Shell House, Ann Street in the City (QLD 4001). The role of the Board Treasurer and Office Administrator, whether the same person or not, was as a financial advisor/bookkeeper.

Ringma modelled his directorship from Bob Bartlett, Director, Teen Challenge Philadelphia, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, United States of America. Around Charles was a team of personable directors for different divisions of the organisational work. John Healey was the Acting Executive Director, delegated as Charles’ representative. Other Office Administrators worked in the Office in the same period, Peter Jones with Brenda Jones as an office worker, and Dennis Everett. Geoff Job was a Centre Supervisor and an office worker, with Cathy Job as a Secretary.

Office workers were conflated as volunteers and stipend paid workers. Full award wages were unheard of in the charity organisation, and it was only Christian trust that keep this small business economy going. The workforce was not unionised, not by principle but by economic necessity, and kept running by the worker’s own professional pro bono attitude. In the last half century, the arrangement has reached a critical point, with the economy being little more than the worker’s self-serving slave labour. The fact is well recognised in the industry, but conservative governments wish it away.

The Organisational Issues of Governance and Administration

The Incorporation of Teen Challenge in Queensland in 1972 would have meant that the organisation had, at least, one Legal Advisor. What is known is that Board member Graham Corney was a solicitor.

Council of Reference

The Council of Reference might have been for show, a process of legitimatization. It did not last long, and there is very little information on the Council, except for who the members were. There were media personalities, one type of showmen. Reg Leonard was probably the most powerful figure. At the time he was Chairman (1971-82) of Brisbane TV Ltd, but he held Chairmanships and Board membership across the Australian media world. Former Church of Christ minister in Annerley, Hayden Sargent started his media career at the Christian Television Association. In those days of the 1960s, he hosted a daily half-hour program, Look, for Brisbane channel TVQ0. In these early days of the 1970s, he ‘pioneered’ local talkback radio at 4BC. He also hosting a daytime talk-back television program, Heartline, produced by Reg Grundy in Brisbane for the Seven Network, and would later hosted local current affairs programs Haydn Sargent’s Brisbane for BTQ7, This Week for QTQ9 and The Sargent Report for TVQ0. His recommendation for Teen Challenge carried much local weight.

There were a few medical show-persons on the Council of Reference, political operators. Arthur Crawford had the third biggest surgical practice in Queensland, it is thought, in the late 1960s. However, his role in the long history was as the Legislative Assembly member for Wavell (1969-1977) for the Liberal Party, and in that parliamentary role a loud and harsh critic of the State Health department and of the socialised medicine. Such a loud critic’s support for Teen Challenge meant that the organisation could overcome the skepticism in the medical profession. Crawford was joined on the Council by Phyllis Cilento. Another controversial figure, the grand old lady doctor, who did had a much softer demeanour than Crawford. Cilento was the conservative progressivist for maternity and child health reforms. Her controversial reputation has returned in recent times. With her famous husband, Ray Cilento, she spoke in very white-centric terms. Although she did not have the outright racism of Ray, as it is contemporarily considered, the naive motherly adornment for racial hierarchy is little tolerated today.

There also academics and associates of the academy among the Council members. The most noted, as an academic career, was Paul Wilson, and yet to be another controversial figure. A criminologist at the University of Queensland, and later Bond University, he would be found guilty of four counts of indecent treatment of a child under 12 years in 2016 from child sex offences (allegedly) committed in the early 1970s. This was an era that Wilson was writing on policing and criminal law courts from a social justice perspective. Hypo-conservatives are extremely unhappy with these exposures from historians. Historians, those good at the profession, breaks the illusion of the good-bad binary. Unfortunately, there are readers who are want the ‘great comfort’ and seek ethical understanding in such traditional and conventional theology, which does stand up to the historical scrutiny. Again, fallible persons in the landscape must be seen. This is no less true for Teen Challenge Inc.

The rest of the Council members were still being called ‘men of the cloth’ in the early 1970s. The Rev. Dr. Charles Geoffrey Noller was an academic associate with his wife, Patricia Noller, an internationally renowned professor of psychology. Charles and Patricia Noller came from New South Wales for Charles to become the Director of Lifeline Brisbane in 1971. From his career in LifeLine, Noller became involved in Legal Aid, Drug Arm, and the Family Council of Queensland. He also became a teacher in the short-lived interdenominational Brisbane College of Theology. Most of these local religious ‘showmen’ were well-known to each other in the small township mentality of Brisbane. It is not a negative criticism, but a factor in personality type. Religion is theatre and it is performance.

On the scale of the religious hierarchy among the Council members was Felix Arnott. Archbishop of Brisbane from 1970 to 1980, the highly educated Arnott was the closest thing Queensland Anglicans had as a public intellectual, and, as such, the churchgoing ‘ratbags’ regarded him as a dangerous theological liberal. Much of the criticisms of the hypo-conservatives was socio-political, although that could not be admitted. The height in the discord arrived in Arnott’s role as a member of the progressivist the Commonwealth royal commission on human relationships. At the annual diocesan synod in June 1978 Arnott decried against the erosion of civil liberties in Queensland, and, like Charles Ringma and Noel Preston, endured the self-righteous wrath of the Nationalists.

The Protestant mainstream in Queensland were moderately liberalising Christian believers, as were the remaining two members of the Council of Reference, Rev. Gloster Udy and Rev. Dr. Lew Born. Gloster Udy was a Director of Lifeline and would during his career served on the staff of the General Board of the Methodist Department of Evangelism in Nashville. Lew Born is a lesser-known figure but as Director of the Methodist – then also Uniting – Director of Youth People/Christian Education he was highly influential in a soft evangelicalisation through the camping movement.

The Council of Reference was brief in time and does not appear to have done much. However, in starting a progressivist enterprise in the early 1970s, it was important to have the Council of Reference as a ‘showboat’ from the high society Felix Arnott to the ‘touch-of-the-common man’ Lew Born. From the backroom power play Reg Leonard to the motherly Phyllis Cilento. It calmed nerves in the pews and installed confidence across radio and television.

Board of Management

The real power for Teen Challenge Inc., in terms of setting directions and capabilities, was in the hand of the Board of Management. Many of the members of the Board have been referenced across the essays. The dominance of the Assemblies of God has been noted – Rev. Ralph Read and Rev. Gerald Rowlands, with Charles Ringma, are at the top of the list, joined by F.G.B.M.F.I. Keith Kelly, Pastor Gary Swenson and Pastor Roy Short. The Board’s moderating voices to this Neo-Pentecostal outlook were Methodist Minister Wal Gregory, Presbyterian Minister Harvey Pollock, Church of Christ Minister Ted Watson, Chartered Accountant Don Usher and state public servant Gary Uhlmann.

The Organisational Issues of The Outreach Issues Including Ventures and Tours

As in all humanity, Charles Ringma had/has different parts of his personality. The personally of an AOG minister is the work in the concept of outreach. The lost become saved and are brought from the street into the ‘temple’ – middle class church congregations. It is more than a fishing exercise but, at its basics, this is what outreach is. This was the reason why Charles was reluctant to start Jubilee Fellowship. He had hoped that Teen Challenge converts would be integrated into the established churches; theologically, this is understood as sanctification. Culturally, the old Catholic doctrine of there being no salvation but as the Church (Body of Christ) became there are no true Christians except on the cushioned seats of the Megachurch. The lives of the young converts changed the lives of Charles and Rita. The counterculture thinking never disappeared by the time Jubilee Fellowship became an ‘established’ and regular congregational gathering. Charles, over time, articulated polite institutional critiques in his writings, but under the politeness the majority of Jesus-informed Christians believe that the Church (institutionally) had betrayed Jesus Christ, the son of God.

In Christian literature that critique is becoming more forthright, over the last half century, and openly defiant since the betrayal of the Evangelical Right in the Trump era.

AOG Branches

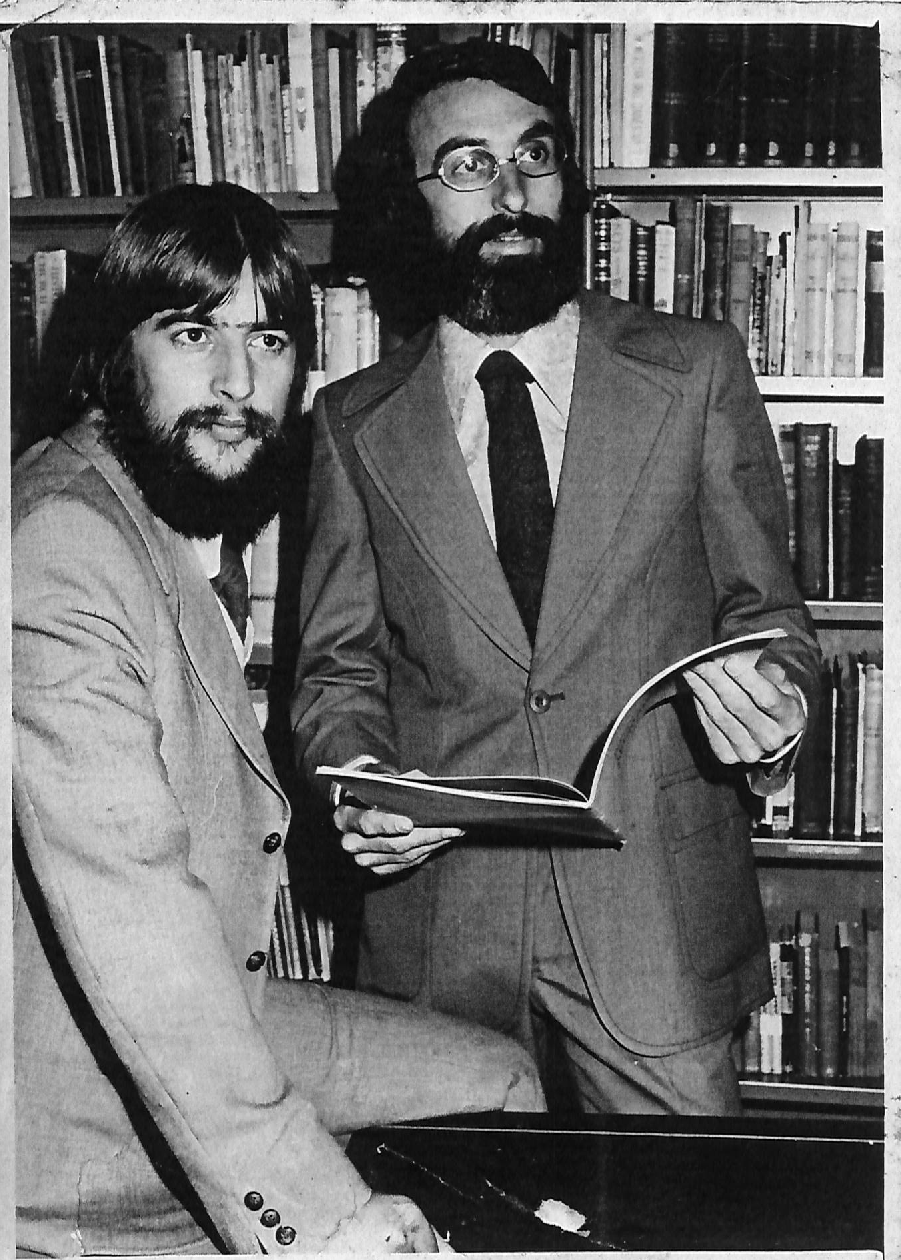

There was a period of hope for AOG churches in the late 1970s and the 1980s and 1990s. For a quarter of century, AOG churches were active in Teen Challenge Inc. with official branches in regional centres. For example, among the early TC branch leaders centred in the local AOG churches were Berend and Moss Boer, the Townsville Contacts; and the Pauline Peake, Toowoomba Worker.

In the era before the Charter Towers and Toowoomba physical facilities, this was the only way that Teen Challenge Inc. could achieve regionalisation.

Figure 4. Teen Challenge Inc. Folk, circa 1974. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The Organisational Issues of Activities of Media, Rehabilitation, and Education (Prevention)

The activities of Teen Challenge Inc. across time and space can be explained under the organisational headings of Media, Rehabilitation, and Education (Prevention).

Figure 5. Discussing Teen Challenge Promotion in the Office. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Media

The point has been made above that those members of the Council of Reference were showmen and show-woman for Teen Challenge Inc. We have also seen Board members, particularly the ‘men of the cloth’ were also performers. Hadyn Sargent was not the only local radio and television personality to promote Teen Challenge. Chris Adams, a local radio personality, was one of the early office workers. His role was in developing a publicity program for the organisation.

Media is an important feature of the counterculture. It has to out-message the mainstream. The centre of operation was there in the beginning, in 1972, called, Jesus People Action Groups, with the P.O. Box 88, South Brisbane 4101. These were the days when the bulk of communication came as paper-based letter writing. The early Teen Challenge Inc. periodicals had different titles, starting with ‘Rag Writer’. They were typed and wet-print duplicated two or four sheet newsletters or rag newspapers. Undergraduate-orientated hand-produced comics dominated the visuals. Charles Ringma was the Editor, Philip Horwood was the Layout Artist, and Delene Lancaster the Typist.

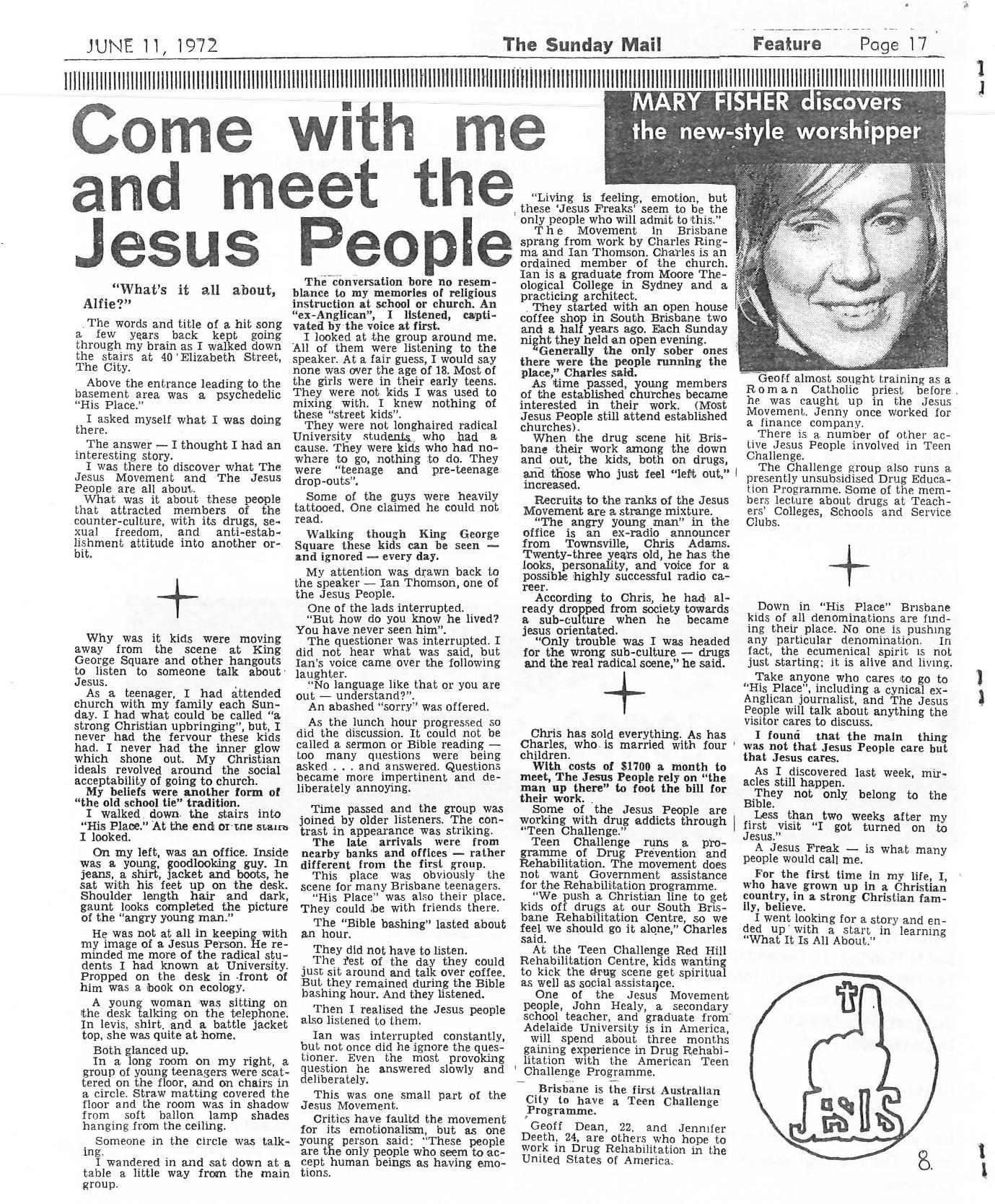

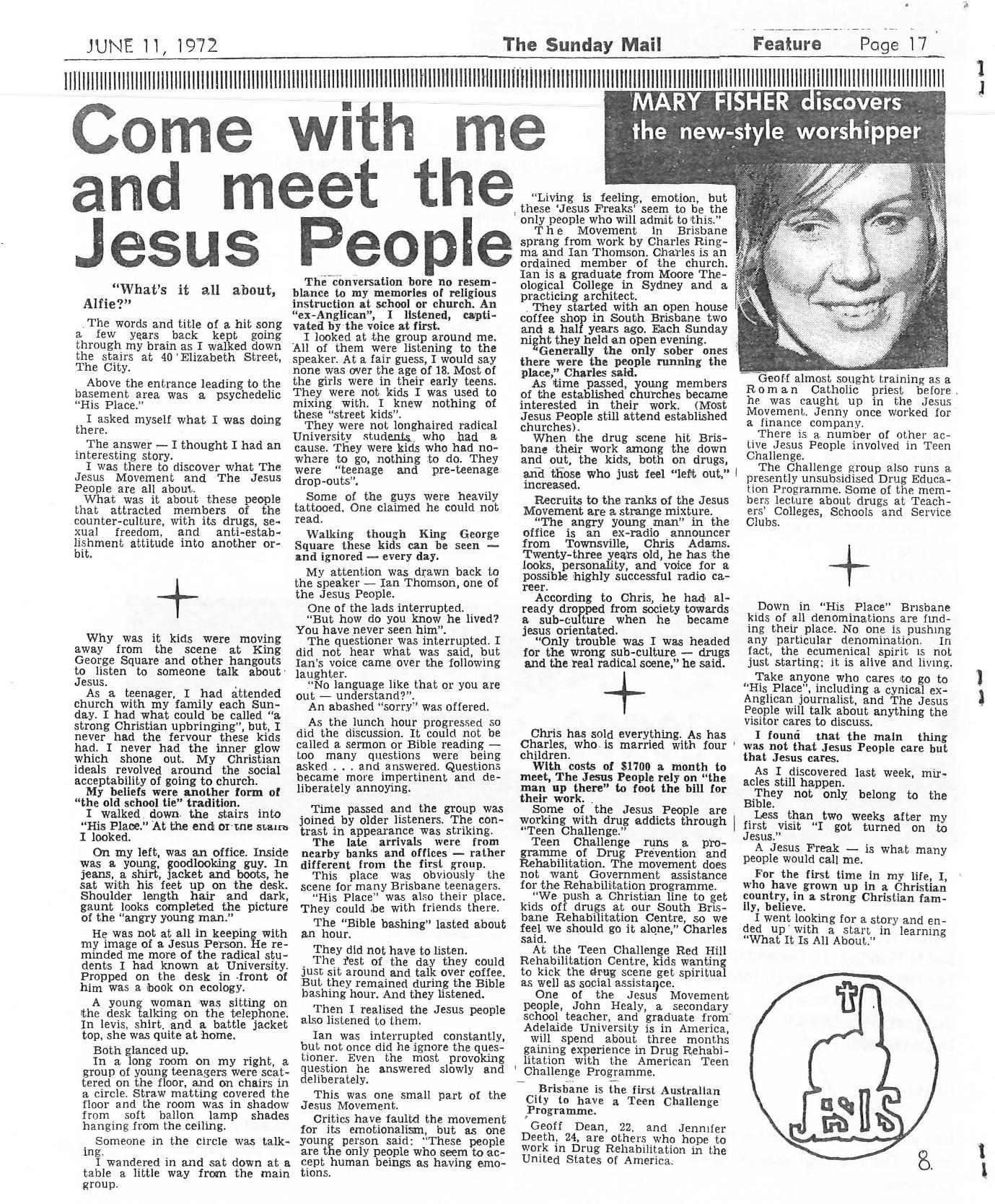

The Queensland News Corp began to splash several articles on Teen Challenge, usually on a first section page in its dailies. The role of Reg Leonard has been noted as a significant figure, a TC ally who headed up a media empire in these days of diverse media ownership. Of the articles the most transformative was that of Mary Fisher, a Sunday Mail Reporter. Fisher explains half a century later:

“When I wrote that first article on Teen Challenge, The Sunday Mail gave me a major ‘by-line’ on the front page of the Features section. This is the photo that went with the ‘by-line’. It was a week before my 24th birthday.

Up until then the editors had not been impressed, in fact very unimpressed by my writing.

That was the day they later referred to as my becoming a good writer.

I believe it was our Lord enabling me.

I have so much to be grateful for.

So grateful

Love in Christ”

The Teen Challenge narrative was transformative on the newspaper pages in 1973-1974 when the organisation was fresh news. That continued for some time, but it could become a double-edge sword, as when in 1977 Charles’ image was ‘front page’ news, among a group of clergies who opposed the positioning of the Joh Bjelke-Peterson regime. Newspaper readerships are prejudicial and newspaper owners play on the prejudice.

Figure 6. The TCTI Logo, circa 1982. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Figure 7. Mary Fisher’s Ground-Breaking article for Teen Challenge Inc. in The Sunday Mail. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Rehabilitation

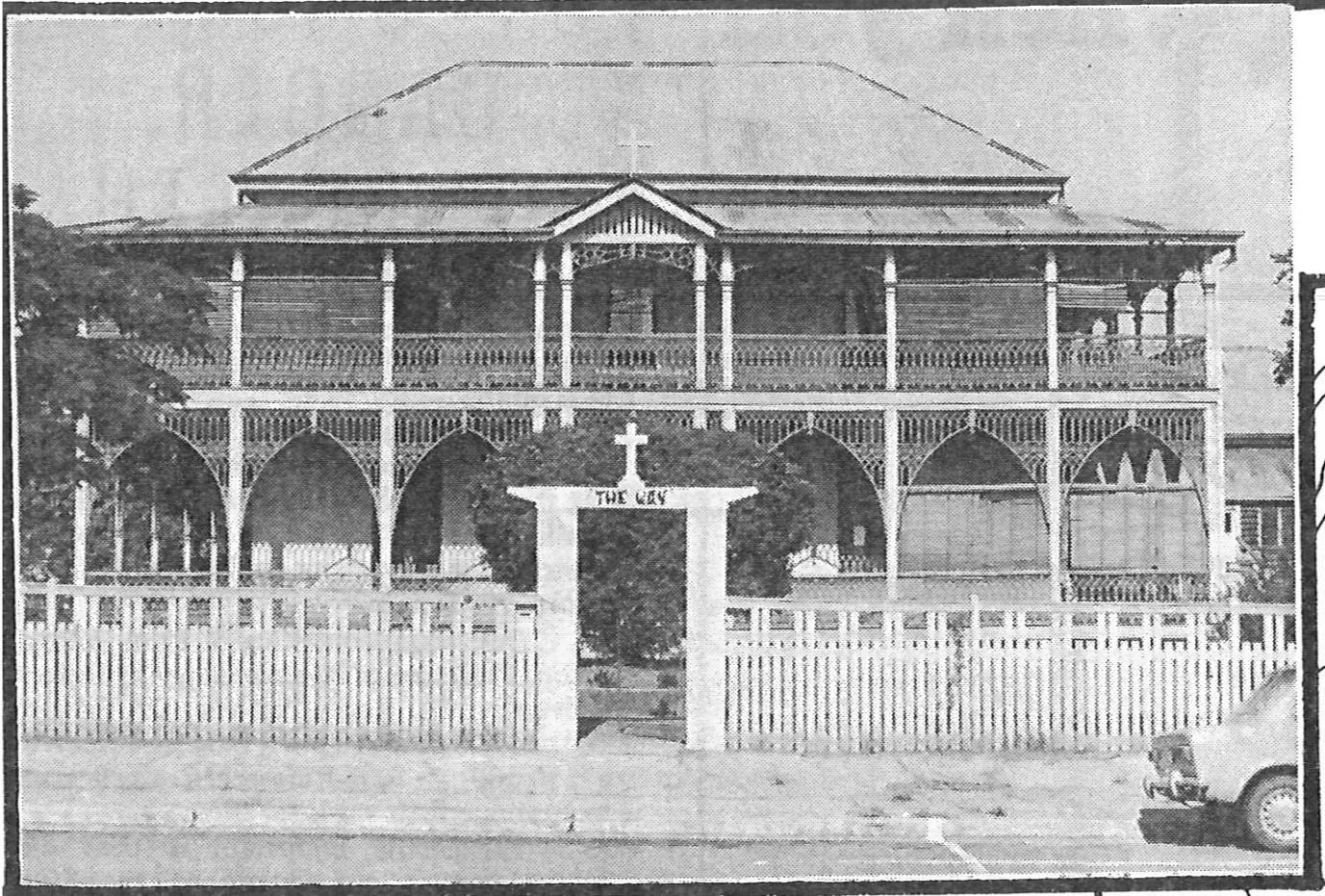

The backbone work of Teen Challenge was drug rehabilitation. The work was also heavily organisational, beginning even before 1972 with Charles Ringma as the Manager, and early residents-workers, Joyce K and Mac Campbell, for The Way Office and Outreach Residence, at 1 Peel Street (cnr. Cordelia Street), South Brisbane (QLD 4101). John Healey began his TC work as an organiser at The Way. Healey was responsible for the Open House Bar-B-Q on the 26 August 1972. During 1972 Charles and Rita moved out The Way to establish a home, as the Executive Director’s Residence, at 34 Gresham Street, St. John’s Wood, Ashgrove, QLD 4060. It operated as a second headquarters for the Teen Challenge Office. Terry Gatfield became the Director, at The Way Centre, partnered with Rosemary Gatfield, another valuable TC worker.

Figure 8. The Way (Good News Centre), 1 Cordelia Street, South Brisbane. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Charles Ringma as Executive Director, Peter Lane as Rehabilitation Director, Dot Lane and Doug Boyle as Rehabilitation Workers, had the work of the TC men’s rehab at Enoggera Terrace, Paddington; it is referred in the records as, Enoggera Road, Red Hill (QLD 4059). However, the exact location has yet to be marked in the Teen Challenge Mapping program.

In 1973 John Healey was formally appointed Teen Challenge Rehabilitation Director, Brisbane. In these years 1973-1974 there were unnamed drug rehabilitation managers and organisers across the country. One has been named in the records as Rodney Hickman, Support Worker, NSW Teen Challenge Inc., NSW Teen Challenge Support Group, 87 Macleay Street, Potts Point, (NSW 2011). In these fledging days of incorporation, and in the failure of Australian federation, the New South Wales work, and then the Victorian work, and then the South Australian, operated separately and the ignorance abounded of who did what.

By 1975 Peter Lane was the Rehabilitation Director, located at 103 Simpsons Road, Bardon (QLD 4065). In the same year, Gary Swenson, Lorna Swenson, Rita Ringma, worked as Manager and Co-Manager, Counsellor, at the Teen Challenge Inc. Girls Home, Red Hill. A few years later saw the acquisition of the Rathdowney Farm as a rural facility, and the Teen Challenge Drug Referral Centre was set-up at 9 Hall Street, Paddington (QLD 4064). By 1980 the Rehabilitation Appeal was launched.

A previous essay has picked up on the role of Koinonia Drug Rehabilitation Centre, Teen Challenge Inc., as a story of short-lived hope for bigger things to come. It had to wait until the new century, but the early players were Neil Paulsen, Sue Paulsen, Roy Calic, Lyn Calic, Margaret Robertson, John Moutou, Mike Bellas, Mike Power, Chris Cummings, Neville Buch, and host of names not listed here.

The official opening of the Kedesh Male Rehabilitation Centre was to be the 3 May 1987 but the guest of honour, Reg Yake, died before he got to Brisbane. Instead, the Re-Dedication of the Kedesh Male Rehabilitation Centre went ahead on 15 December 1988, at 254 Flinders Parade, Sandgate (QLD 4017). Rick Raetz was the Co-ordinator. Little remains on records for the Maleny Rehabilitation Farm and the Sunshine Coast Rehabilitation Centre.

Figure 9. Graduation of Kedesh Male Rehabilitation Centre, 1987. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Education (Prevention)

The TC workers were progressivists. The programs were not only about picking up the damaged after the fact. Teen Challenge Inc. was about the education for prevention; preventing young people falling into a drug habit.

In 1972 the program was a matter of a small visitation with the coordination of a few high school teachers, such as the Cooroy State High School I.S.C.F. Outreach. Larger High School Visitation Teams were then formed, such as the Teen Challenge Chinchilla High School Visit. This included John Healey (Director), Jeff Ganter (Graduate), Josephine Horrochs (Team Assistant), and Chris Adams (Director of Drug Awareness).

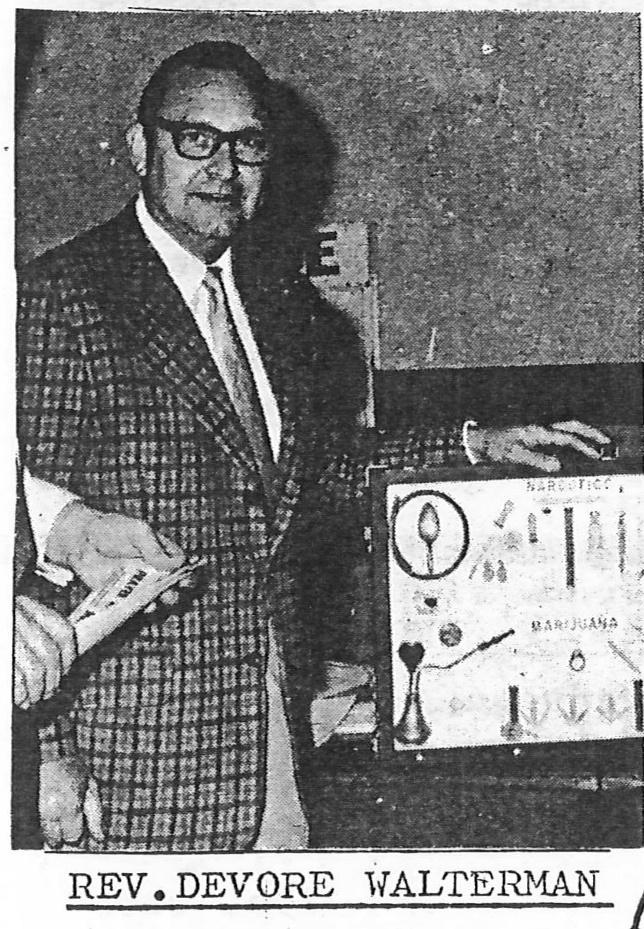

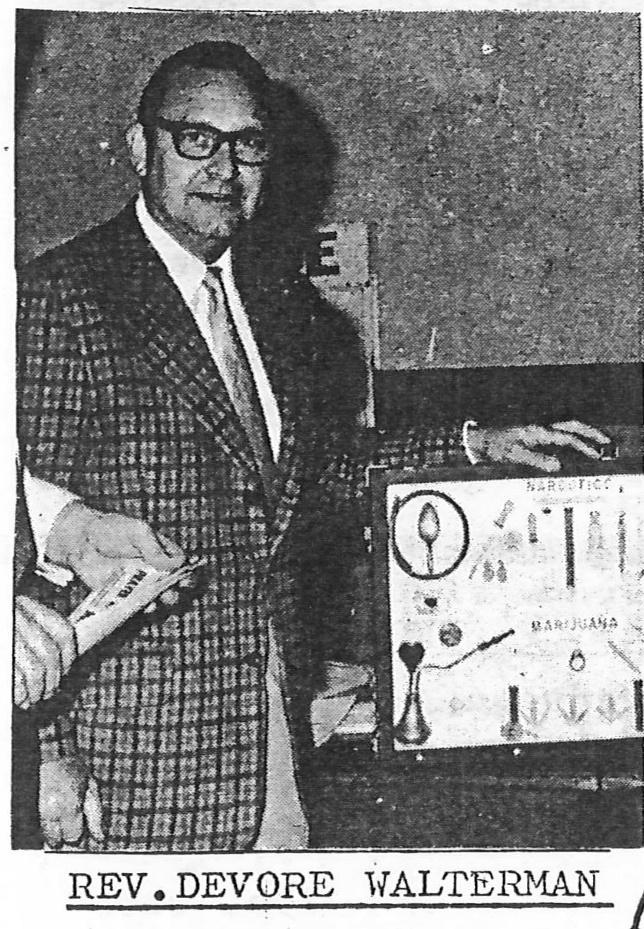

Figure 10. The De Vore Walterman event. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The year 1973 gave a lift with the visit of De Vore Walterman, Executive Director, US National Council for Prevention of Drug Abuse, and speaking at Brisbane Drug Awareness Meetings. The messaging went something like Teen Challenge Inc. is ‘the Jesus Movement’ to the dangerous ‘The Drug Sub-Culture.’ The problems of the culture are deeper than addiction and answers lies in transforming young persons into a redeeming culture (Christian). The messaging appears conventional for the American thinking, but the challenge underlying the messaging was the alignment with contested United States drug policies. Between blanket prohibition and blanket permissiveness were a host of realities of which the likes of De Vore Walterman struggled to understand. In the Australian setting Charles Ringma was more in tune with the way drug policies were double-edged and contradictory.

Education: Teen Challenge Training Institute

Both for drug rehabilitation and education, heart of the organisational operation was the Youth Workers Training Seminar, which became the National Teen Challenge Diploma Training Course (one year long), operated as the Teen Challenge Training Institute (TCTI).

In 1972 John Healey trained for two and half months at the San Francisco Teen Challenge Center. This became the basis for the Brisbane training program with Australian modifications. It appears that it took a few years for the training to be formalised as a full seminar program. In the week of 14-18 January 1974 Healey organised the Evangelism, Counselling and Youth Problems Seminar at the West End Methodist Church, Vulture Street, West End, (QLD 4101). The other trainers included in the seminar program were Charles Ringma, Athol Gill, Chris Adams, John Carrol, Jim Christian, Greg Job, Bob Pearson, and Gloster Udy from Sydney.

By 1978 Charles Ringma began his part-time clinical teaching with the University of Queensland Medical School, on social medicine and legal and illegal drug abuse. The year 1981 saw the chaplain Brendan Scarce became the National Director, the role being in actuality the National Teen Challenge Diploma Training Course (one year long). Charles functioned in the first year of the course as the National Director, and the course eventually moved to include interstate Teen Challenge organisations and to which the social worker Brendan Scarce had prime responsibility.

Education: Queensland Pedagogies (and research).

A few analytical observations can be summarised as the research pedagogies. In 1971 Charles Ringma is the LifeLine researcher to find the most appropriate service, what is coined AOD – Alcohol and Other Drugs. The binary between ‘alcohol’ and ‘other drugs’ expresses the confusion in the social model with the vague category of ‘Other’. In that mix is other pedagogies. There is the educational mix an expression of social fears about the dark world and also a fascination with the underworld drama, common to the thinking in American liberal art colleges of the era. It is picked up in the language of De Vore Walterman, and of Dave Wilkerson’s Cross and Switchblade.

The Teen Challenge education required more, and it was delivered in the connections to the leading Queensland Christian educators, such as Rev. Dr. Lew Born, the Director for the Methodist Department of Christian Education. And the few academics associated with Teen Challenge added another layer – academics such as the criminologist Dr Paul Wilson, who in those days was Acting Head of Department, Anthropology and Sociology, University of Queensland. Charles continued his role as a researcher, and by 1976 he has begun the B.A. degree part-time at The University of Queensland majoring in Sociology and Studies in Religion.

Figure 11. John Healey leads the Teen Challenge Chapel Service, circa 1973. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

ACTIVITIES

The buzzword for pedagogies in the last half century has been praxis, the running together of theory and action, activities in the current thinking. What did this mean for Teen Challenge Inc.? The rationale behind the facilities which the organisation ran provided theoretically based action, or put another way, or action shaped as theory.

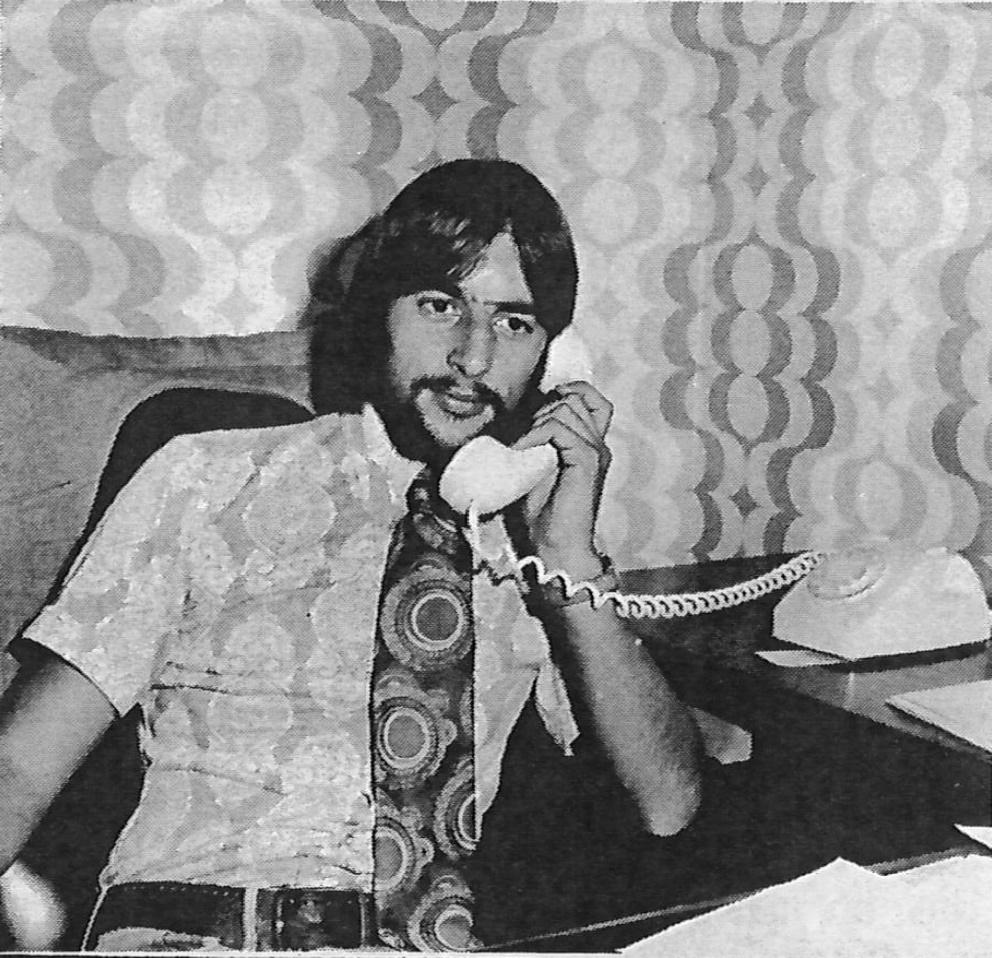

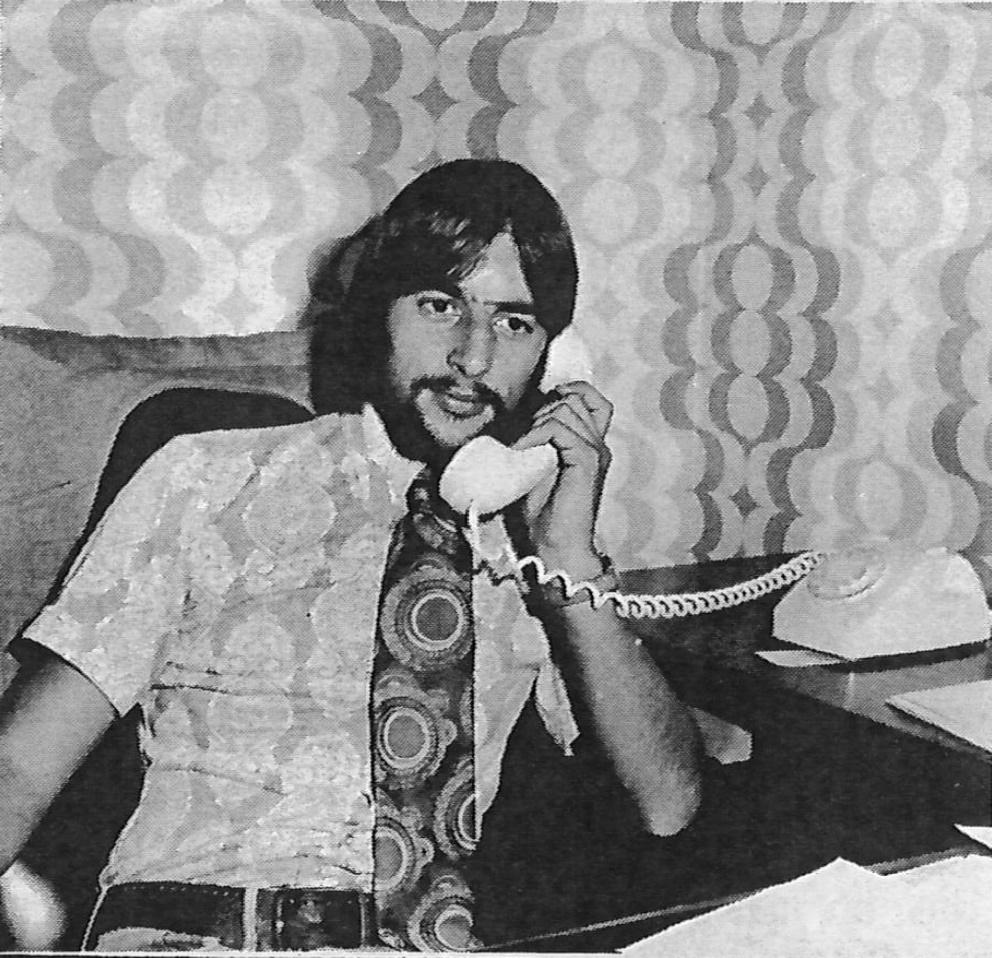

Phone Communications ministries

The shift in communication theories were coming from different directions but they overlapped in the action. Indeed, communication action was another buzz phrase. The global names which buzzed in the local scene in the decade of the 1970s and 1980s were theorists headed by John Dewey, Jurgen Habermas, Marshall McLuhan, Theodor Adorno, Antonio Gramsci, and George Herbert Mead. Many more names could be added, but these six philosophers and sociologists were immediately recognisable. The names stretched across a large part of the mid-twentieth century. McLuhan coined the expression, ‘the medium is the message’. The idea that that a communication medium itself, not the messages it carries, is the revealing focus of study. It is beyond the full explanation here but goes to the beginning of Teen Challenge Inc. in the activities of the phone communications ministries, which started as a connection between the first coffee shop, ‘His Place’, and LifeLine. The Phone medium is the Interactional Model of communication. It is bidirectional, where two persons send and receive messages in (hopefully) a cooperative manner as they continuously encode and decode information. Compare that earlier medium to the social media today. Communication on these new mediums is chaotic involving many more than two persons.

Figure 12. Chris Adams ‘on the phone.’ Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Back in 1972, soon the ministry became known as ‘Teen Dial’ with an office outfit at 19 Eagle Terrace, Brisbane City (QLD 4000). How long it stayed in the expensive area of city properties is uncertain. Harvey Pollock became the LifeLine Coordinator with Teen Challenge, based at the Teen Challenge Inc. Head Office, Enoggera Road, Red Hill (QLD 4059). Oversight came from Charles Noller, as the Director, Counselling, LifeLine, and the TC Council of Reference member.

Respite Ministry (Farms)

Very little information among the records have been kept on the Teen Challenge respite ministry, closely associated with the rehabilitation program. The activities have to do with the farms leased by Teen Challenge, the first being, in 1974, the NSW Teen Challenge Farm, in Connabarabran, (NSW 2357). Very little is also known of the Rathdowney farm. It appears that the urban rehabilitation centres were utilised for the main part of the program. The farms provided respite spaces for both clients and staff members, leaving urban pressures behind, with some geographic distance.

Figure 13. Teen Challenge Rathdowney Homestead Retreat, circa 1974. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Primmer Lodge and Hebron House

More is known of the urban houses in Teen Challenge Inc.; however, the purpose of the essay is only to sketch the organisational history. More will said in the book, and feedback is welcomed.

The 1977 opening of Hebron House (emergency short-term accommodation) began a period of organisational renewal. Located at Milton Road, Toowong (QLD 4066), Mike Hobbs was the Director for Homeless Youth, Hebron House. Terri Hobbs was a Support Worker, as was Mark Cleaver, Helen Wallace, Tony Bennett, Gary Sivyer, David Smith, Paul Cummings, Steve Jeanerret, Mike Hobbs, Philip McLennan, Mike Power, Terri Hobbs, Liz Payne, Margaret Robertson, Janice Jordin, and host of names not listed here. Philip McLennan became the Director in 1980, and Mark Cleaver was the Children’s Services Co-ordinator for Hebron House. Other TC Workers also were Children’s Services Co-ordinators: Helen Wallace, Tony Bennett, Gary Sivyer, David Smith, Steve Jeanerret, and Paul Cummings. In 1984 Mike Power became the Director with Alec Spencer beginning his stellar rise in the organisation as a Hebron House worker. Spencer would become the Hebron House Director in 1987.

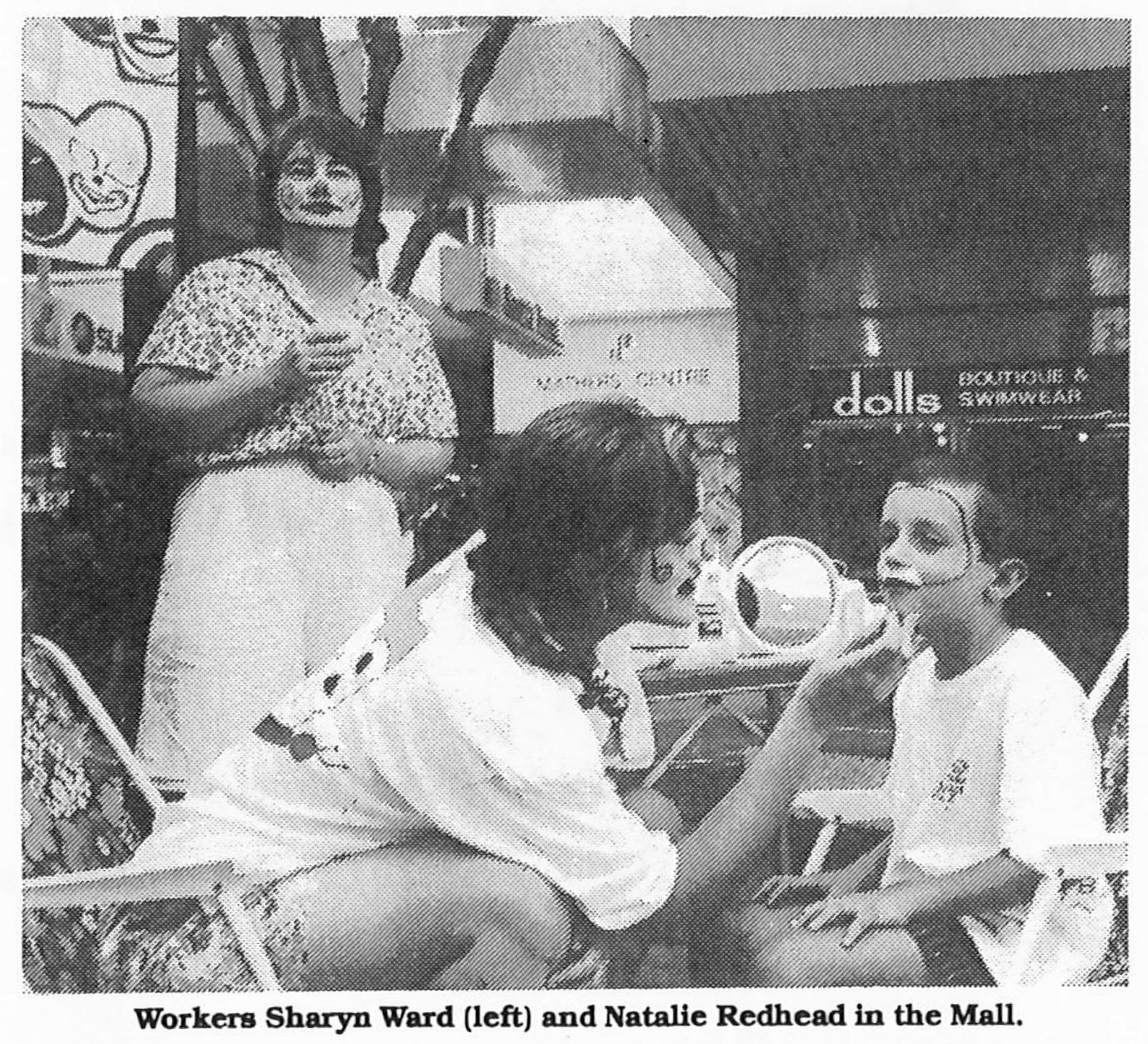

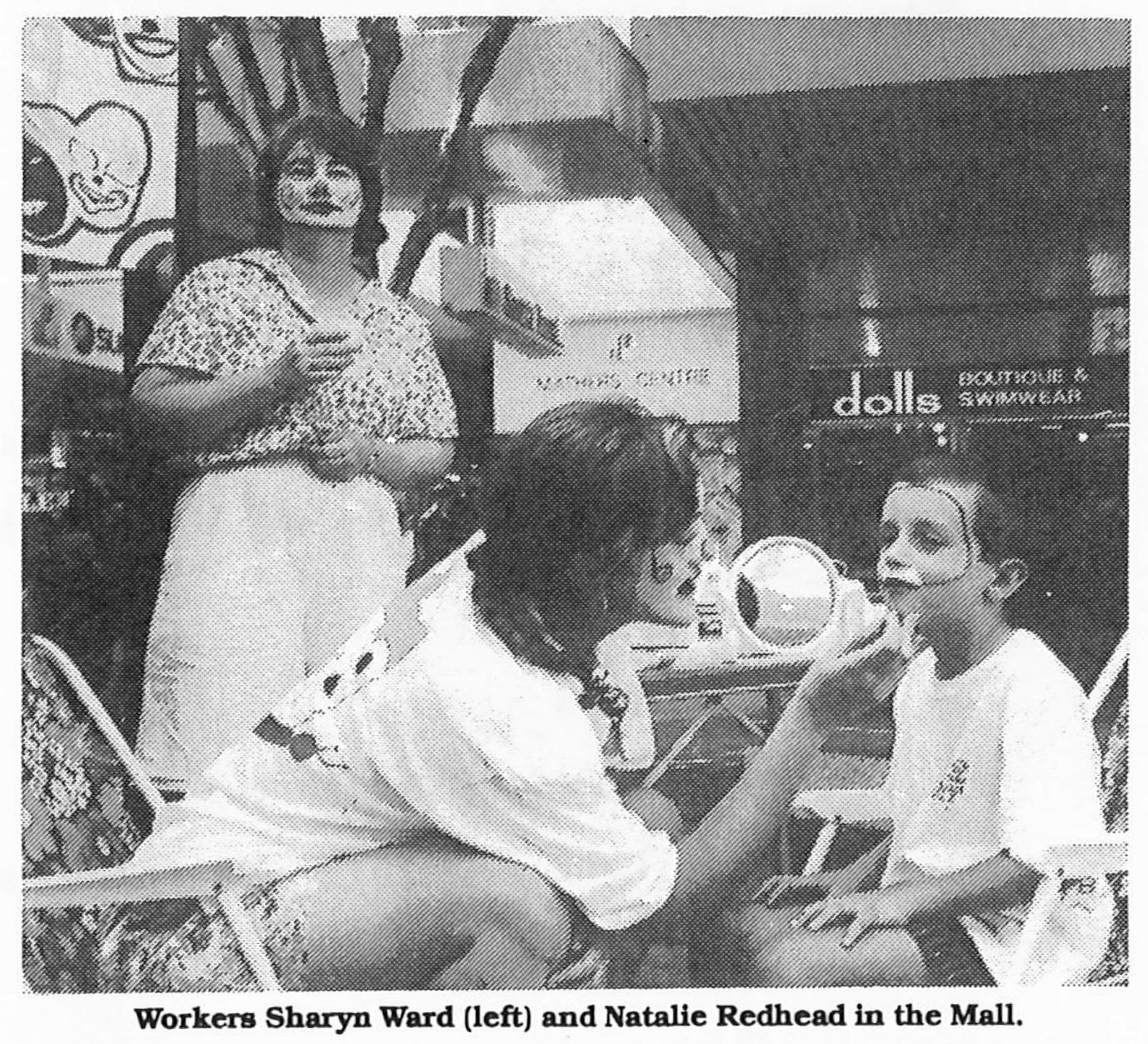

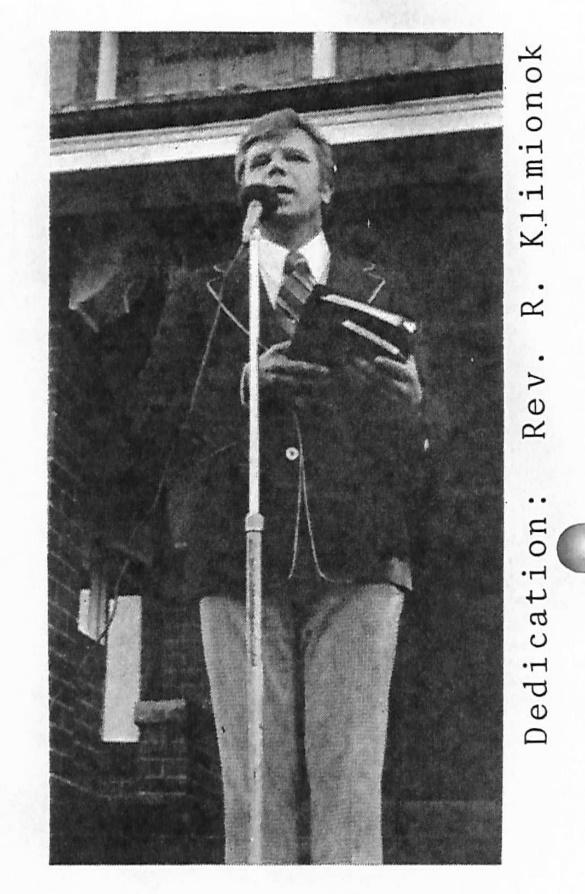

In 1978 the Minister for Welfare, John Herbert, officially opened Primmer Lodge (long-term support accommodation). This was a watershed moment in Teen Challenge Inc. A growth in TC volunteers formed around Primmer Lodge, at 18 Bellevue Parade, Taringa (QLD 4068). Among the volunteers recorded were Peter Allen, Brian Gibson, Liz Payne, Sue Peel, Ros Stark, Gary Uhlmann, Chris Cummings, and Peter Wilson. The Primmer Lodge workers included Lyn Meier, Helen Wallace, David Smith, Marylin Smith, and Jean Claude Boulenaz was the Manager.

Figure 14. Pastor Reg Kliminonok, speaking at the Opening of Primmer Lodge, 13 May 1978. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

The moment tended to overshadow the organisation work for the men’s and girls’ homes, in Paddington and Red Hill. Gary Swenson, as the Manager, of the Teen Challenge Girls Home, and Lorna Swenson, as a Co-Manager, is important to the story but little is known.

It is hoped that the set of online essays will provide more detailed information from comments offered up.

Youth Activity Centre

The front door to Teen Challenge Inc. was, for several decades, the Youth Activity Centre at Alfred Street, Fortitude Valley (QLD 4006). There were several TC directors, Tony Bennett and Wayne Porritt among them, and other workers who passed through the Centre, Alan Ruthford among the earliest in 1975, when Teen Challenge Activity Centre, actually began at the Focal Point Arcade, Wickham Street, Fortitude Valley (QLD 4006). Claire Fielding was a stalwart in the centre over the decades until the early 1990s.

Figure 15. The Offical Opening of Teen Challenge Activity Centre, 1982. Source: Teen Challenge Inc. (Qld)

Prison Ministry

In the organisational background, out of the limelight, was the TC Prison ministry, based at the old Brisbane Goal (‘Boggo Road’), Annerley Road, Dutton Park (QLD 4102). The tireless workers in the ministry were Doug Boyle, Norm McIntyre, Margaret Robertson, Shirley Allan, and Claire Fielding.

Rallies and Concerts

There was an informal side to the Teen Challenge Inc. which involved rally and concert promotion in the office environment. Tickets were sold, sometimes as an event of promoting the Teen Challenge mission, such as the Nick Cruz Rally in 1975, or as a fundraising event as in the 1976 Andrae in Concert. In both of these cases the venue was the Festival Hall, Alice Street, Brisbane City (QLD 4001). These were events that had a megachurch feel in the era before the Brisbane megachurches. The Christian religion was becoming the art of the showman in the ‘mega’ ways – mega Christian rock bands, loud and in your face, and faith was a ticket to entertainment. It was not that there was not something existentially genuine in the experience for the youth of the day. The local Brisbane band, ‘His’, delivering the Pink Floyd version of Jesus the anarchist – we were not going to be another brick in the wall. The Teen Challenge youth of the last quarter of the twentieth century became the leaders of the local Church. What has escaped the attention of the institutional Church, in its talk of orthodoxy, is how heretical the history is.

Concluding Remarks

The working for the history during 2022 will need assistance from past in present voices. Much more is to be done on the welfare agency, Good News Centre working with alcoholics in South Brisbane, and the office volunteers, such as Joyce Krassenburg, who is only a name in the records.

New Governance and Administration invested in Workers.

With small organisations, it very common that governance and administration is in the hands of the ‘ordinary’ or ‘labouring’ worker. There are partial stories collected.

Even as Teen Challenge Inc. expanded, the habit of a worker-leader continued. The organisation was among those that did not abide the rigid distinction of modern capitalism between those who laboured and those who managed labour. In the postmodern world the distinction has become an absurdity. Nevertheless, for any organisation it is almost impossible to completely get rid of a hierarchical outlook, given enough tasks and the time to do it in.

In thinking how much more of the story has to be told, consider a snapshot picture sometime in 1975 at the Teen Challenge Inc. Head Office, Enoggera Road, Red Hill (QLD 4059), or the relocation to Head Office, (Woolworths Shopping Centre) 107 Latrobe Terrace, Paddington (QLD 4064).

There is the leadership of Geoff Dean, a worker from the Catholic Tradition, who unknowns to him, would create a scholarly career from the work in the decades ahead. In that office environment were regular visitors, Hans Booy, the TC Campus worker; Ian Thomson, TC Worker, Architect and Moore College graduate; and Glenda Reinhardt, Rehabilitation Worker. There is Harvey Pollock, the Business Deputation Worker, chatting away. Peter Jones and Roslyn Stark are barely listening as office workers. Forms and other records have to be completed.

Please help, much more is to be said.

by Neville Buch | Jan 25, 2024 | 2023 American Tour, Concepts in Public History for Marketplace Dialogue, Intellectual History, Literature (Fiction)

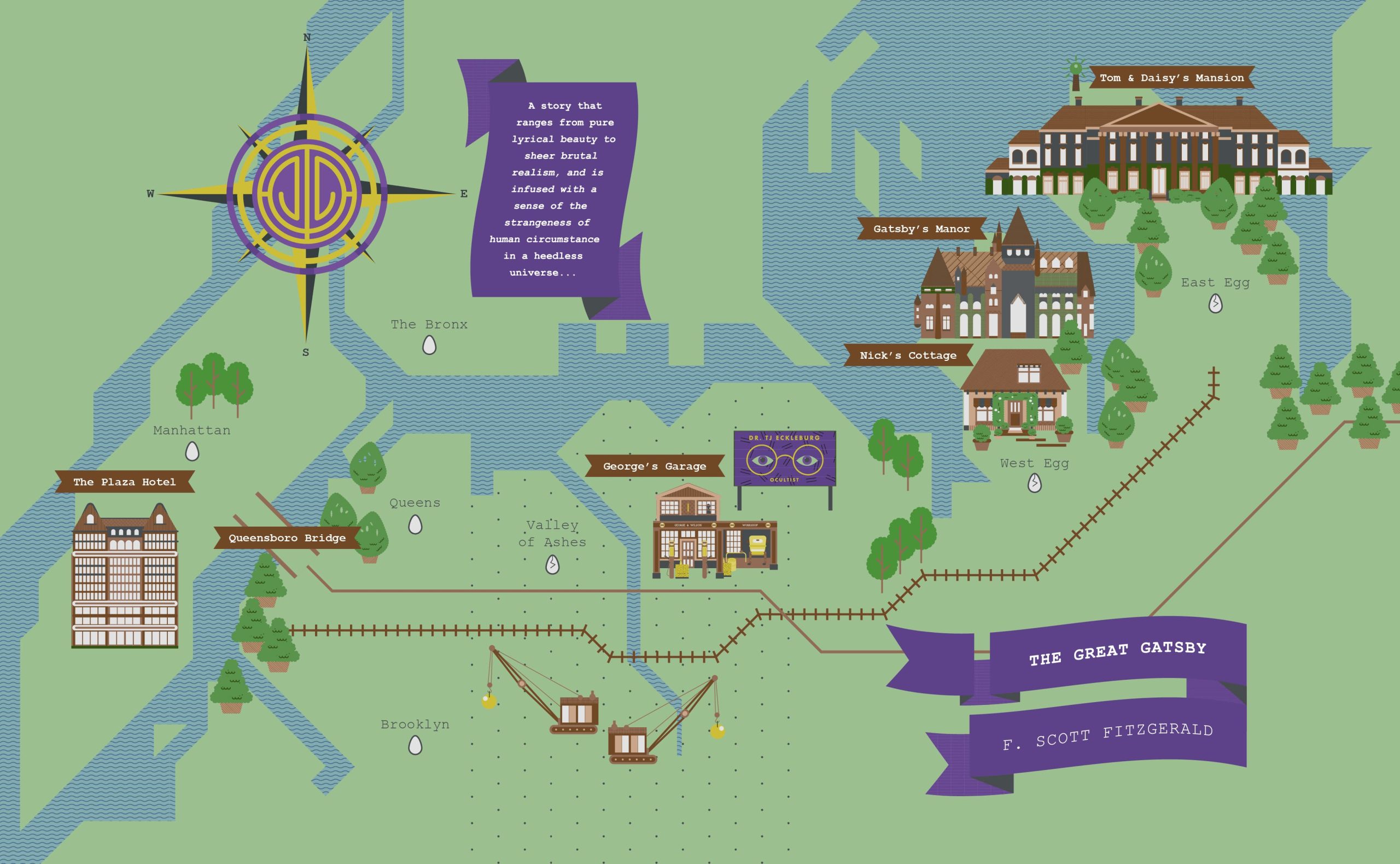

Synopsis: A review of F. Scott Fitzgerald‘s The Great Gatsby (read copy, Penguin Books 1950, 2008 edition). The book was published in 1926, from notes of 1922 and as set in New York’s Long Island and Manhattan Island in 1922. The landscape of the narrative, is considered, in the first section of the review, with reflections of a 2023 tour around the geography of The Great Gatsby, a hundred years later. The second section is a discussion of personalism from the book, and the third section makes a few comments of the relationship of the book and the messages of American modernism in the 1920s, considered a century later.

CONCEPT OF LANDSCAPE

Re-reading novel The Great Gatsby and watching Baz Luhrmann’s film (2012 trailer), The Great Gatsby, I realised I had been in the novel’s fictional geography, albeit a century later, during my 2023 American research tour. The film re-creates the fairly accurate sense of the novel‘s historic landscape, but fails to capture well the novel‘s personalism and cultural modernism, as American modernism was just emerging as literature in 1922. Henry James’ theme of New York’s binary of old money and new money is there, but added is the modern thematic visionary of Sinclair Lewis‘ Main Street (1920). If you wander around American townships you inevitably find a Main Street, somewhat updated, but nevertheless in both the intellectual and parochial small-mindedness which Lewis described in the early twentieth century. The more things change, the more it does not; a paradox of any intellectual history. Perennial themes in new or recycled frameworks. I had spent an afternoon in Main Street, Northport, Long Island.

Image: Main Street, Northport, 10 Feb 2023

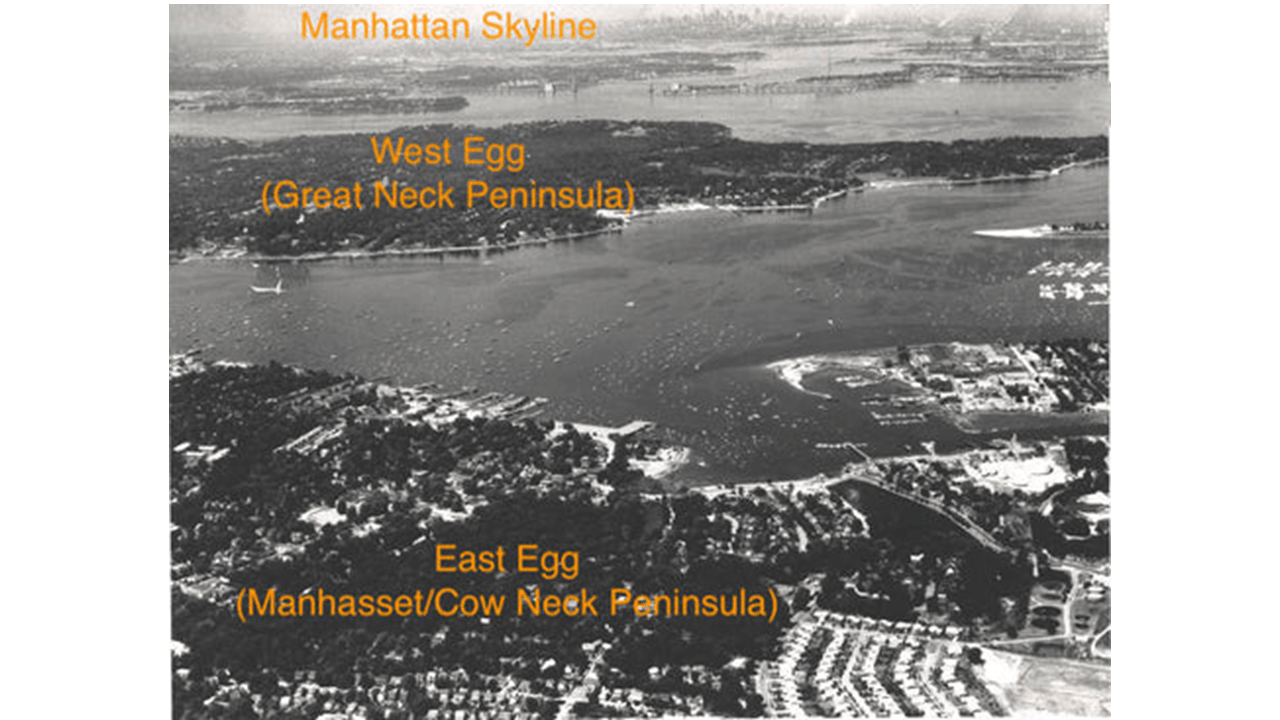

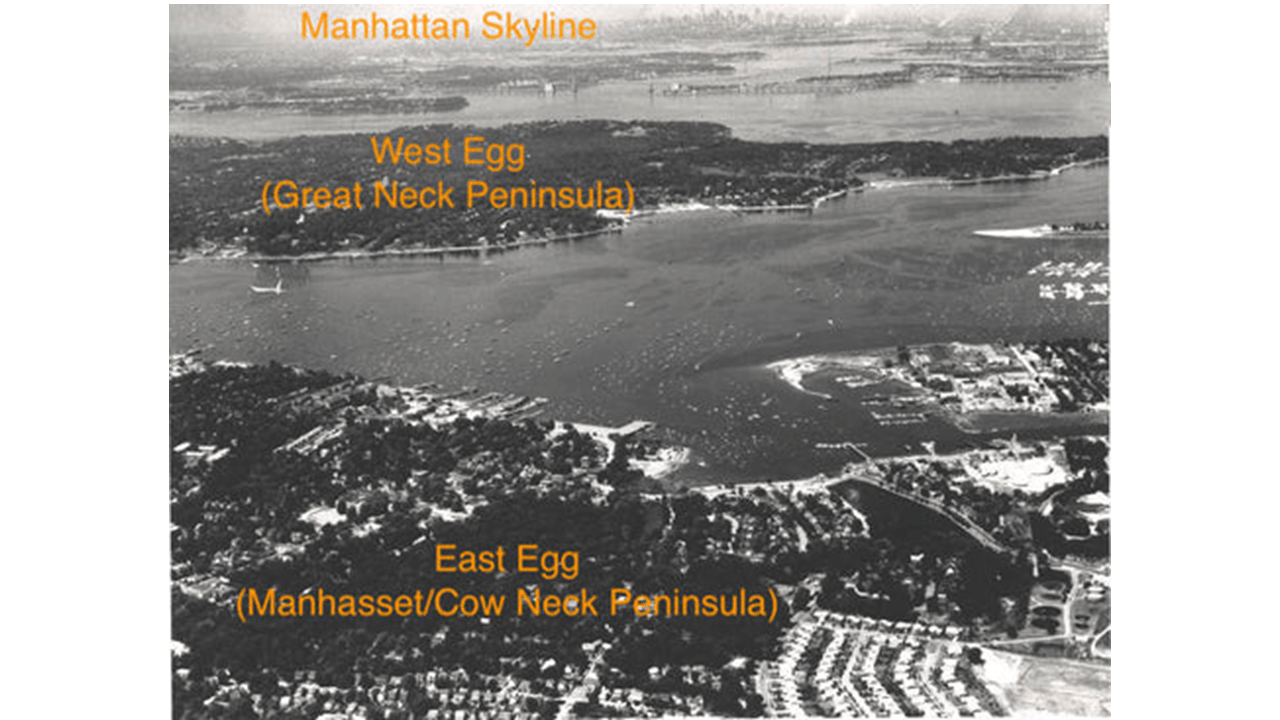

This is not the part of Long Island of Fitzgerald’s geographical recreation, using different names but with the same contours and pathways which existed. But the Centerport-Northport area, which is further east than Fitzgerald’s Manhasset Bay area, is a good place to start, as it is the location of Vanderbilt Museum and Planetarium, what remains of the ethos of the Jay Gatsby’s mansion, on an island famous for playboy mansions and parties.

Image: Vanderbilt Museum and Planetarium, Centerport (2), 10 Feb 2023

Image: Vanderbilt Museum and Planetarium, Centerport (2), 10 Feb 2023

These days the beaches of northern Long Island are more inviting to the American middle classes, and basically gone are the symbolic representation of the old-new moneyed Gilded Age. Summers are full of young families less concerned with the cultural prejudices of modernism. Sophisticated and moneyed hedonism is less to be seen on the summer vacation, but with the remaining private mansions some of the ethos lingers in the shadows.

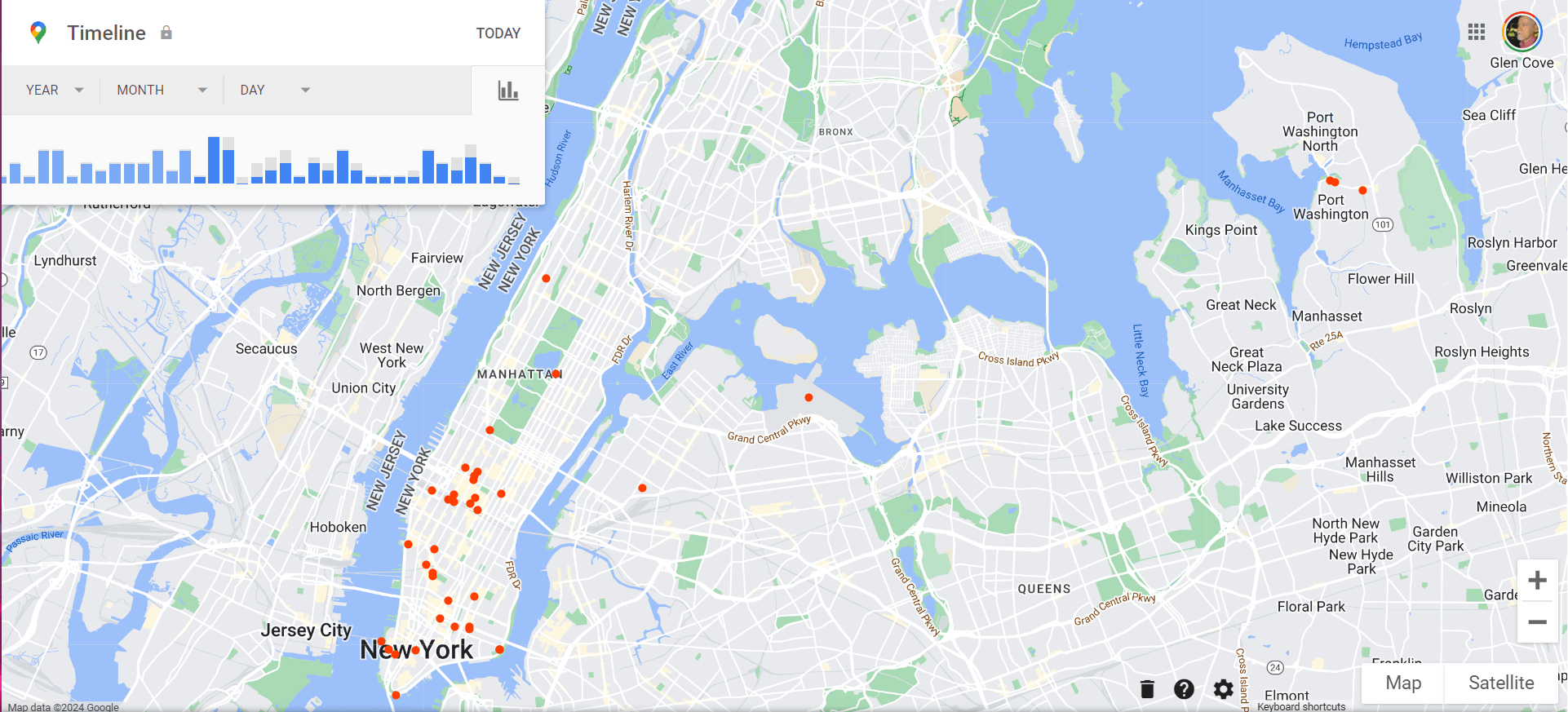

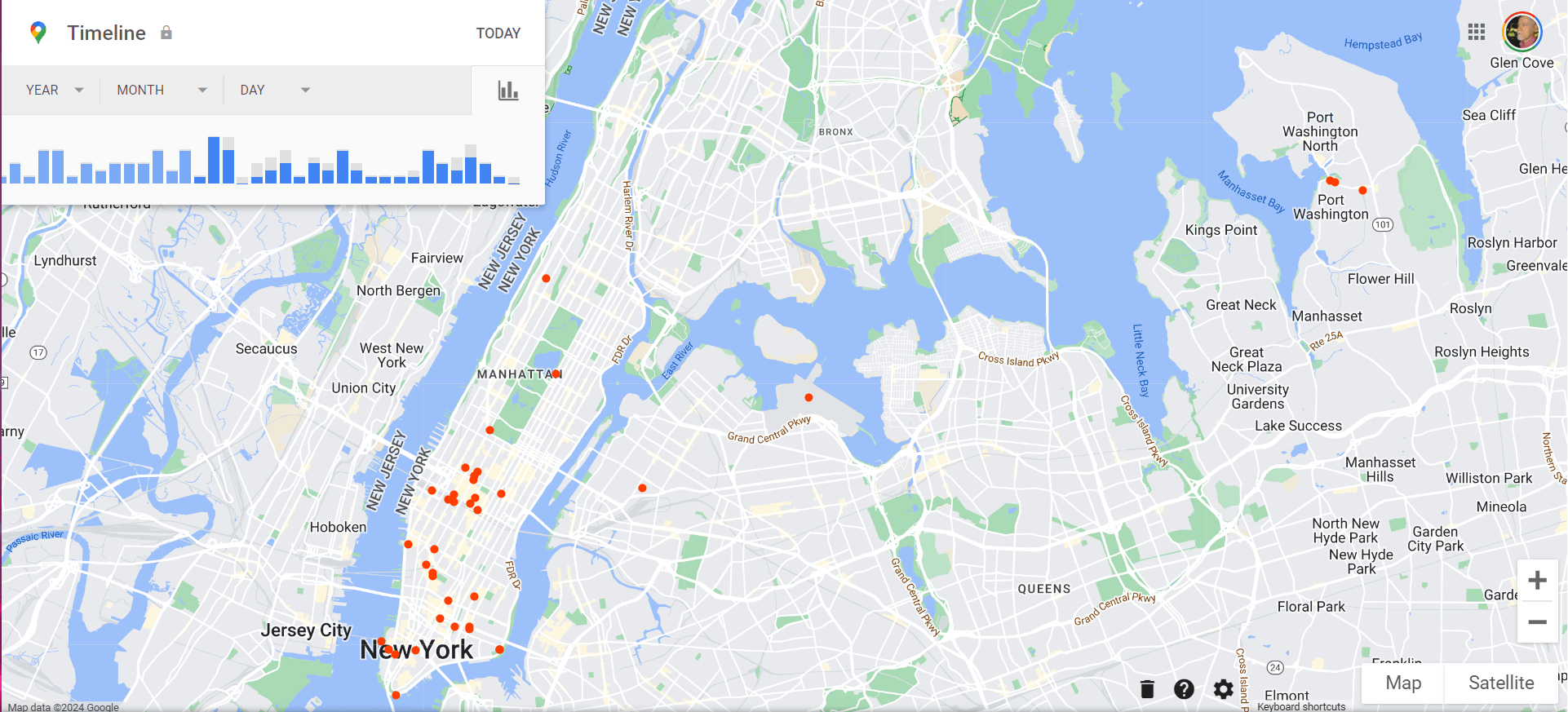

Image: Neville at Centerport Beach, 10 Feb 2023

When not being driven in fast automobiles, Nick Carraway transverses between the ‘West and East Eggs’ area and Midtown and Lower Manhattan by the Long Island Rail Road (LIRR). It was a February sunny afternoon I headed out of Pennsylvania Station on a journey to Port Washington, joined by my travelling host, Herb Klitzner, in Queens. This meant traveling through the Fitzgeraldian geography. At the time I had not taken the significance of the journey. I was on my way to the Port Washington Library with Lewis more in mind. The Library had a good size collection of Lewis’ papers and first edition books, but also had a few Fitzgerald reference materials. Lewises and Fitzgeralds were known to each other, mixing in New York literary circles during these early years of the 1920s.

Image: Neville at the Port Washington Library between the Fitzgerald and Lewis collections, 11 Feb 2023

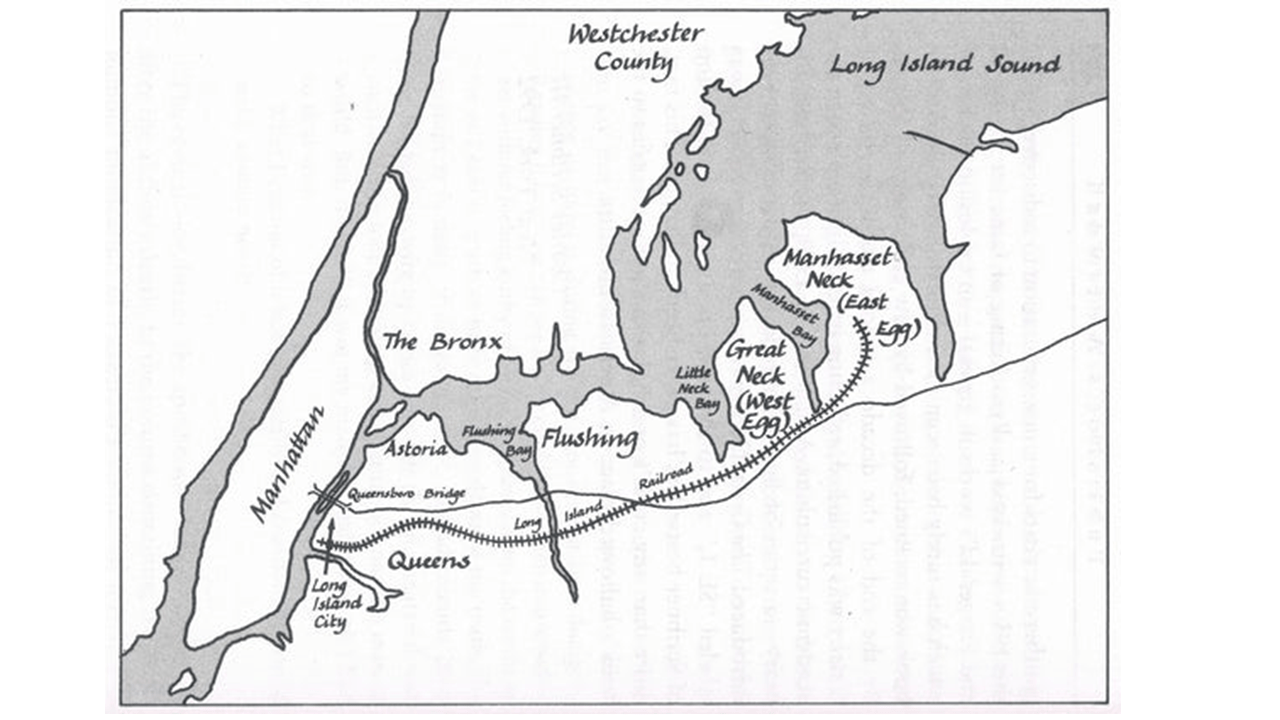

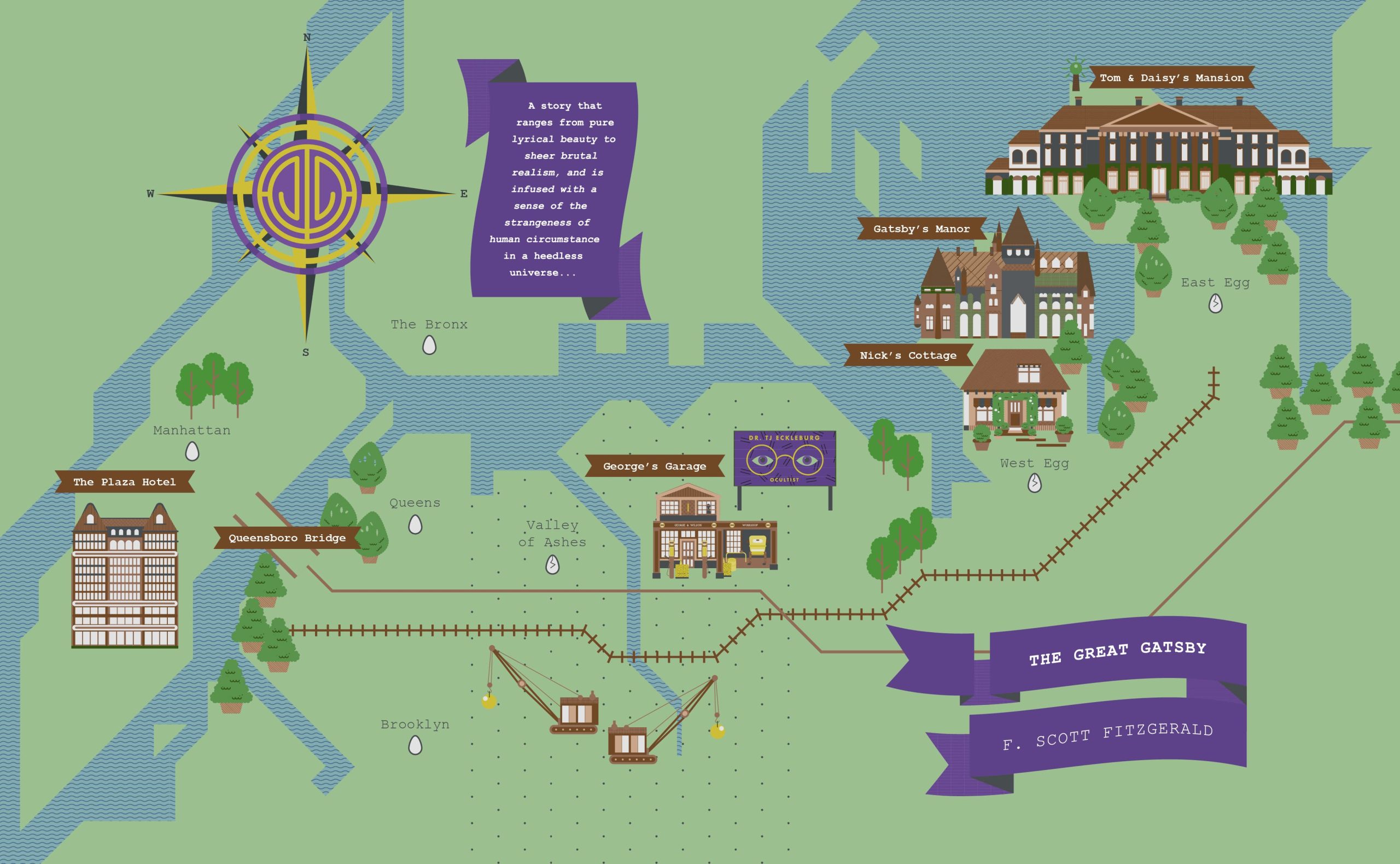

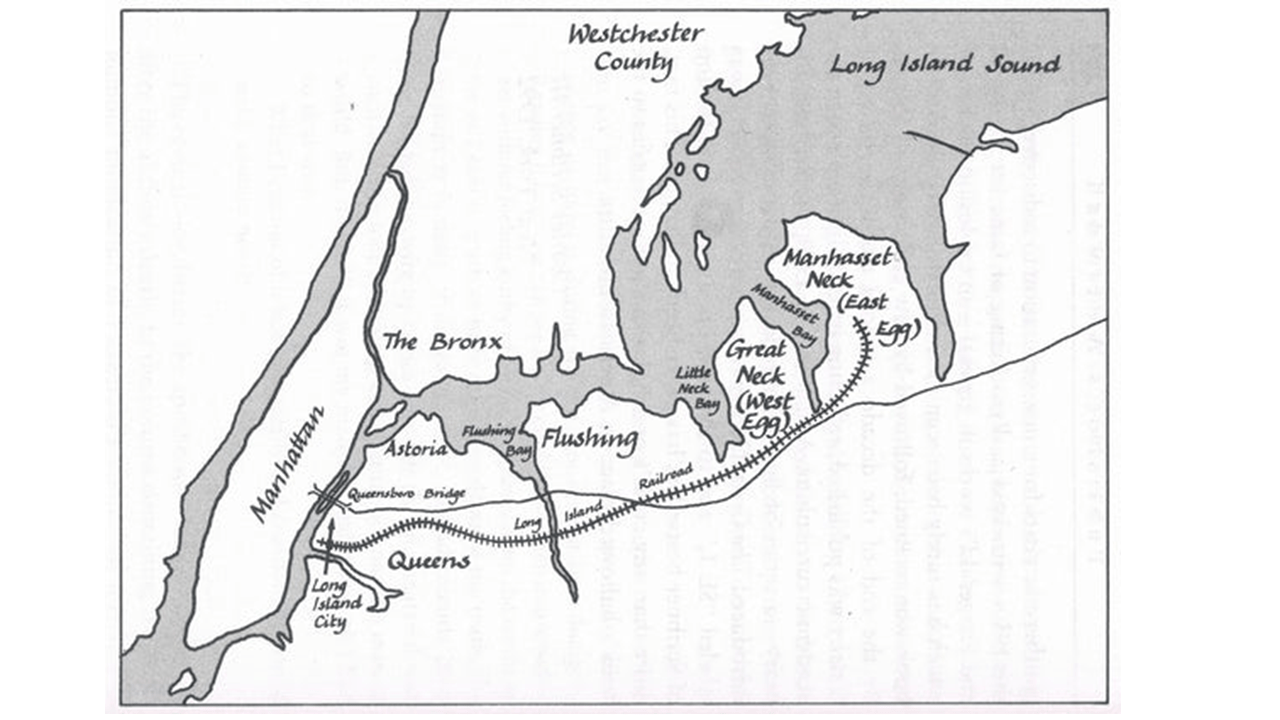

The trip to Port Washington is basically the same in 1922 but the appearance of the landscape has changed greatly. The webpage, Century Press, Letter No. 7 – Gatsby’s Geography, helpfully matches the novel’s fictional names to the actual Long Island sites.

Image: 1920s Sketch Map NY to LI. From Century Press, Letter No. 7 – Gatsby’s Geography, https://www.centurypress.ca/blogs/letters-from-century-press/letter-no-7-on-gatsbys-geography

Image: Neville’s Travel Map in the New York-Port Washington Area, Feb 2023

Flushing (true name) is part of Queens where George Wilson’s Garage is located, stared at by the eyes of Doctor T.J. Eckleburg’s billboard. Jay Gatsby’s mansion is in the fictional West Egg (new money) and is actually Great Neck. East Egg is the area of the Buchanan’s mansion, and more precisely it is Plum Point, looking across the Bay to Gatsby’s Kings Point. Plum Point is just north of Port Washington. The fictional/actual Valley of Ashes is just across from the Queens railway stop (as in 1922), on the other side of Flushing creek which has been mostly built over, and exposed as Flushing Meadows Corona Park.

Source: http://treadwellburket.mtaspiring.edutronic.net/the-great-gatsby-analysis-settings/

The desolate scenes of the novel are gone, except in the evidence of swampland, feed from the Long Island Sound.

Image: View from the Long Island Railway journey, 11 Feb 2023

The landscape viewed in 2023 is not the imagined landscape of Fitzgerald in 1922. What we have to imagine are desolate hamlets, coastal villages, set through small inlets and lightly forested and narrow roadways. There are only a few old black and white photographs which capture the 1920s landscape of the Long Island playground.

Image: 1920s Aerial Image of Gatsby Area. From Century Press, Letter No. 7 – Gatsby’s Geography, https://www.centurypress.ca/blogs/letters-from-century-press/letter-no-7-on-gatsbys-geography

The landscape of the early 1920s Long Island speaks to us of American modernism. Visions of relaxing suburban life outside of the madness of the Megacity, and yet the truth was that it came with the Valley of Ashes. It is the industrial dumping site, a significant representation of industrialisation in the landscape, which in the twentieth century came and went, and the prosperity of the Jazz Age had long gone with the loss of this economy.

CONCEPT OF PERSONS

There are two main frameworks in thinking about the concept of persons. Personalism, a diverse set of philosophical doctrines on what a person is, and Philosophical Psychology, as oppose to therapy, and is the explanatory basis for psychology.

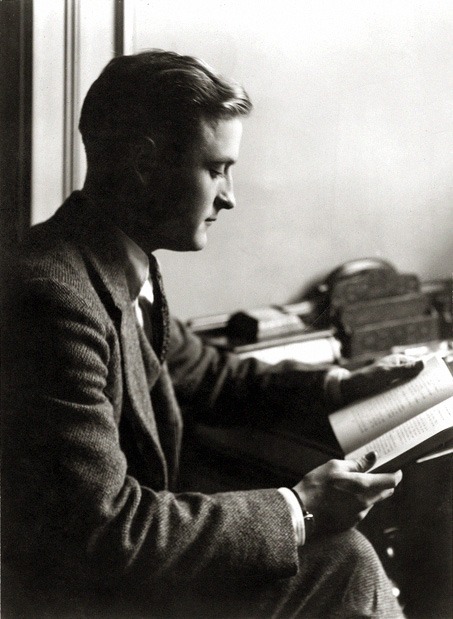

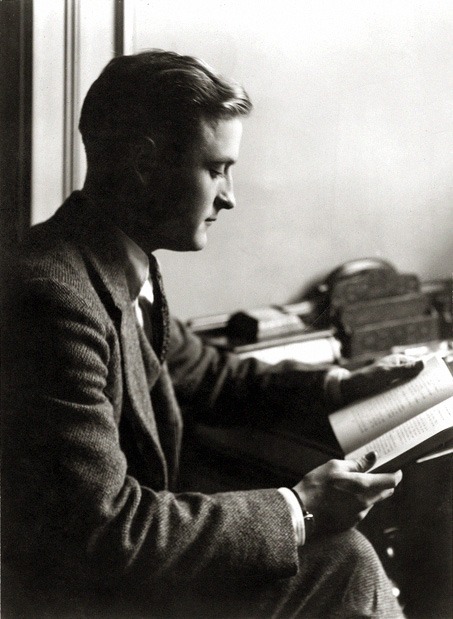

Wikipedia Image: A black-and-white photographic portrait of Jazz Age writer F. Scott Fitzgerald. Courtesy of the Minnesota Historical Society. This photo appeared on the rear of the original dust jacket of Fitzgerald’s second novel, The Beautiful and Damned, which was published in March 1922 by Charles Scribner’s Sons.

Which any frameworks are being considered, there are common terms to illuminate the thinking of the text: personality, and gendered relations (including sexuality). The philosophic reflection on the text can go much further to types of judgement, caring and carelessness or ruthlessness, and thinking on ourselves and the significant other.

In personality:

“If personality is an unbroken series of successful gestures, then there was something gorgeous about him”

“He smiled understandingly-much more than understandingly. It was one of those rare smiles with a quality of eternal reassurance in it, that you may come across four or five times in life. It faced–or seemed to face–the whole eternal world for an instant, and then concentrated on you with an irresistible prejudice in your favor. It understood you just as far as you wanted to be understood, believed in you as you would like to believe in yourself, and assured you that it had precisely the impression of you that, at your best, you hoped to convey.”

Nick Carraway is not Fitzgerald as the narrator, but it is clear that Fitzgerald, across the novel, is speaking to personalities he came across in his life, before writing the book. It is also clear, from the above quotations, that Fitzgerald introduces persons as the modernist perceives beauty and aesthetics. How many times in the “public relations” rhetoric are we told to smile.

Nick Carraway – a Yale University alumnus from the Midwest, a World War I veteran, and a newly arrived resident of West Egg, age 29 (later 30) who serves as the first-person narrator. He is Gatsby’s neighbor and a bond salesman. Carraway is easy-going and optimistic, although this latter quality fades as the novel progresses. He ultimately returns to the Midwest after despairing of the decadence and indifference of the eastern United States.

Jay Gatsby (originally James ‘Jimmy’ Gatz) – a young, mysterious millionaire with shady business connections (later revealed to be a bootlegger), originally from North Dakota. During World War I, when he was a young military officer stationed at the United States Army’s Camp Taylor in Louisville, Kentucky, Gatsby encountered the love of his life, the debutante Daisy Buchanan. Later, after the war, he studied briefly at Trinity College, Oxford, in England. According to Fitzgerald’s wife Zelda, he partly based Gatsby on their enigmatic Long Island neighbor, Max Gerlach. A military veteran, Gerlach became a self-made millionaire due to his bootlegging endeavors and was fond of using the phrase ‘old sport’ in his letters to Fitzgerald.

Daisy Buchanan – a shallow, self-absorbed, and young debutante and socialite from Louisville, Kentucky, identified as a flapper. She is Nick’s second cousin, once removed, and the wife of Tom Buchanan. Before marrying Tom, Daisy had a romantic relationship with Gatsby. Her choice between Gatsby and Tom is one of the novel’s central conflicts. Fitzgerald’s romance and life-long obsession with Ginevra King inspired the character of Daisy.

Thomas ‘Tom’ Buchanan – Daisy’s husband, a millionaire who lives in East Egg. Tom is an imposing man of muscular build with a gruff voice and contemptuous demeanor. He was a football star at Yale and is a white supremacist. Among other literary models, Buchanan has certain parallels with William “Bill” Mitchell, the Chicago businessman who married Ginevra King. Buchanan and Mitchell were both Chicagoans with an interest in polo. Also, like Ginevra’s father Charles King whom Fitzgerald resented, Buchanan is an imperious Yale man and polo player from Lake Forest, Illinois.

Jordan Baker – an amateur golfer with a sarcastic streak and an aloof attitude, and Daisy’s long-time friend. She is Nick Carraway’s girlfriend for most of the novel, though they grow apart towards the end. She has a shady reputation because of rumors that she had cheated in a tournament, which harmed her reputation both socially and as a golfer. Fitzgerald based Jordan on Ginevra’s friend Edith Cummings, a premier amateur golfer known in the press as ‘The Fairway Flapper’. Unlike Jordan Baker, Cummings was never suspected of cheating. The character’s name is a play on two popular automobile brands, the Jordan Motor Car Company and the Baker Motor Vehicle, both of Cleveland, Ohio, alluding to Jordan’s ‘fast’ reputation and the new freedom presented to American women, especially flappers, in the 1920s.

George B. Wilson – a mechanic and owner of a garage. He is disliked by both his wife, Myrtle Wilson, and Tom Buchanan, who describes him as “so dumb he doesn’t know he’s alive”. At the end of the novel, George kills Gatsby, wrongly believing he had been driving the car that killed Myrtle, and then kills himself.

Myrtle Wilson – George’s wife and Tom Buchanan’s mistress. Myrtle, who possesses a fierce vitality, is desperate to find refuge from her disappointing marriage. She is accidentally killed by Gatsby’s car, as she mistakenly thinks Tom is still driving it and runs after it.

Source: Wikipedia.

The modernist sensibilities are clear, in defiance to Nick’s father’s advice on judgement. Tom is a prig, while Jay is “worth the whole damn bunch put together”. These modernist sensibilities, however, do not escape, criticism of the modernist outlook. Daisy is shallow and George is a brute.

In Gendered Relations:

“He looked at her the way all women want to be looked at by a man.”

“Angry, and half in love with her, and tremendously sorry, I turned away.”

Jay’s quality of personality is mysterious. He has that secret knowledge of knowing the “way all women want to be looked at by a man.” Most men would also like to know. It is not only Jay’s imagined relations with Daisy, the singular and large dream he has build up, symbolised by the West Egg mansion. Nick’s relations with Jordan is also complex and full of illusions. The affairs of the heart are entangled with conflicting emotions and thoughts.

In Philosophic Reflection:

“In my younger and more vulnerable years my father gave me some advice that I’ve been turning over in my mind ever since.

“Whenever you feel like criticizing any one,” he told me, “just remember that all the people in this world haven’t had the advantages that you’ve had.”

“There are only the pursued, the pursuing, the busy and the tired.”

“I was within and without, simultaneously enchanted and repelled by the inexhaustible variety of life.”

“They’re a rotten crowd’, I shouted across the lawn. ‘You’re worth the whole damn bunch put together.”

There is irony in Nick’s final judgement of Jay. Jay’s character had no scruples other than his romantic vision of Daisy as the “nice girl”. He was in the end revealed as the bootlegger in the crime network of ‘Wolfsheim’ who is based on New York gangster, Arnold Rothstein. One of the biggest shortfalls in American modernism of the 1920s, and 1930s, was the celebration of brutal crime and thuggish characters, as if there were no significant moral or ethical judgements; only aesthetical ones. Unfortunately, there is a swing back to this kind of nasty love of criminality in our own time. Swings and round-a-abouts. For example the Ned Kelly mythology is celebrated, and then it is correctly criticised.

Wikipedia Image: Arnold Rothstein, New York Daily News – https://www.newspapers.com/image/391466253/ Daily News 29 Oct 1920, Fri · Page 40

In the more philosophic reflection, this is caring and carelessness or ruthlessness:

“I couldn’t forgive him or like him, but I saw that what he had done was, to him, entirely justified. It was all very careless and confused. They were careless people, Tom and Daisy—they smashed up things and creatures and then retreated back into their money or their vast carelessness, or whatever it was that kept them together, and let other people clean up the mess they had made.”

Carelessness description is a judgement appropriate for Tom and Daisy for most of the novel, but, at the end, when Daisy is vulnerable and Tom take something of redemption, Nick observes a tenderness between Tom and Daisy; after all, Daisy could not declare that there was never a time she loved Tom. It is only that the care within the coupling is exclusive and is careless to others. Daisy is shallow in her judgement, and Tom is an outright white supremacist. Their affective politeness is a matter of class behaviour, not genuine personal caring. When it comes to Wolfsheim or Arnold Rothstein, the situation is outright ruthlessness but masked within civil sensibilities. Against the romantic illusion, such criminals destroyed lives. The character of Jay Gatsby begins as an enigma, but, as his hidden life history is revealed, he is not so much careless or ruthless, but confused of mind. After his death, James’ father, Gatz senior, reveals a son who redeemed himself to the original family, making something of amends for his reckless ambition. His father had been given a house two years before Gatsby’s untimely end. Another aspect of the carelessness is the misjudgment that Nick’s father warned about. Tom had clearly set up George to murder Gatsby under the misjudgment of both Tom and George that it was Jay at the wheel of the vehicle that killed Myrtle. If Tom and George knew that it was Daisy, the judgement would have led in another direction.

In even more philosophic reflections, in how we each think of ourselves and the significance other:

“There must have been moments even that afternoon when Daisy tumbled short of his dreams — not through her own fault, but because of the colossal vitality of his illusion. It had gone beyond her, beyond everything. He had thrown himself into it with a creative passion, adding to it all the time, decking it out with every bright feather that drifted his way. No amount of fire or freshness can challenge what a man will store up in his ghostly heart.”

In the end, it is the capacity to revaluate our judgements that matters. As a good stoic, Nick’s father’s approach was to suspend judgement, but that is, realistically, a temporary position. It is only the romantic who fears disillusion who refuses the need for revaluation in judgement, which means that judgement has already been secured.

CONCEPT OF TIME-PAST

The Great Gatsby is a work that draws out the concept of time-past for us, a hundred years later. It would have been difficult for the readers in 1926 to appreciate the historiography which was only just happening in the emergence of American modernism as literature.

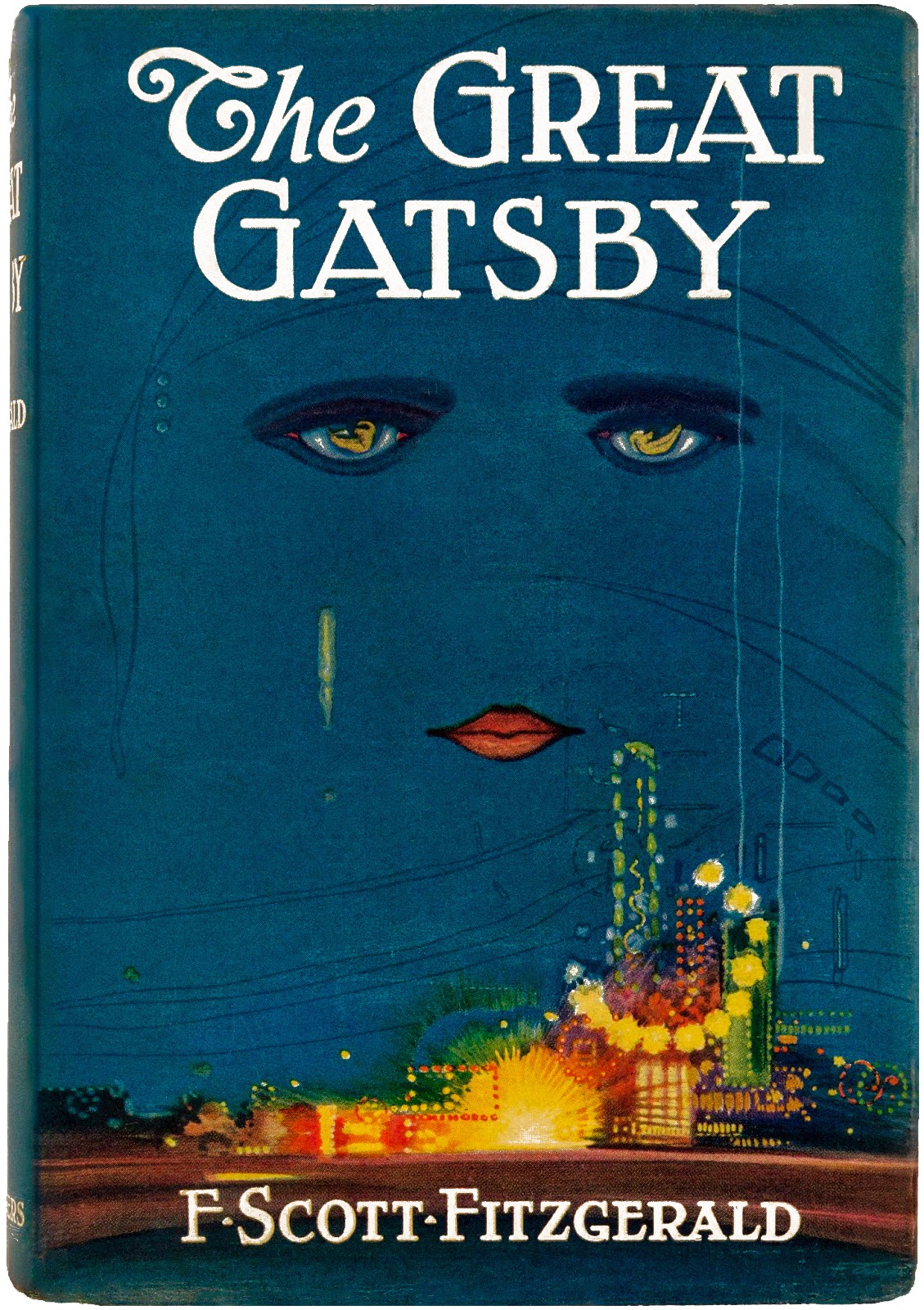

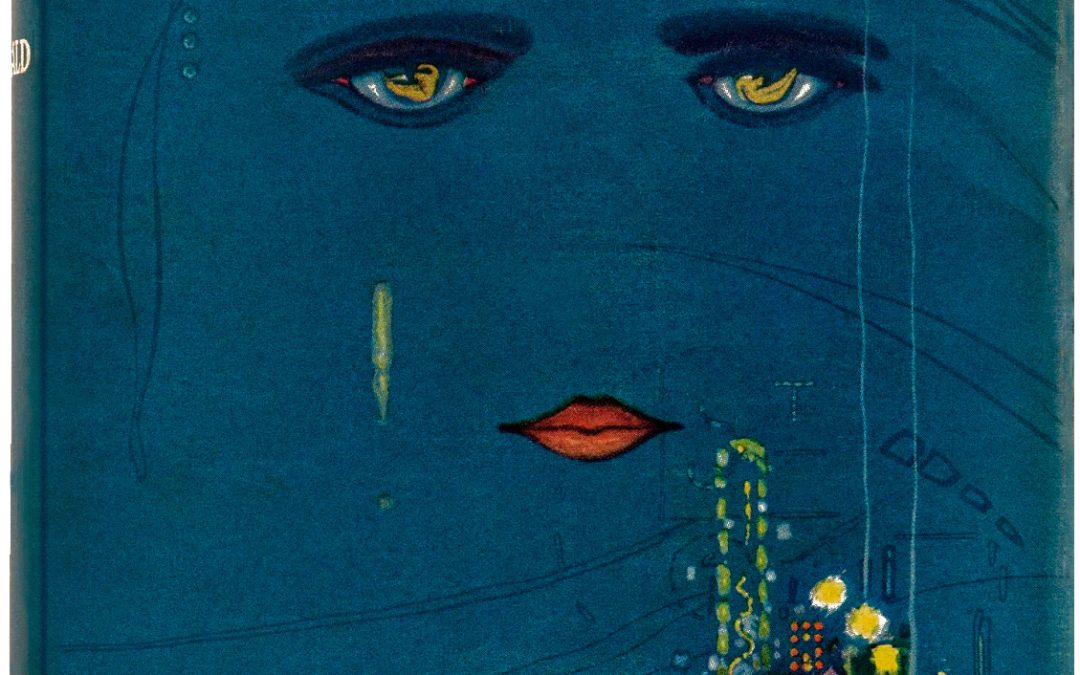

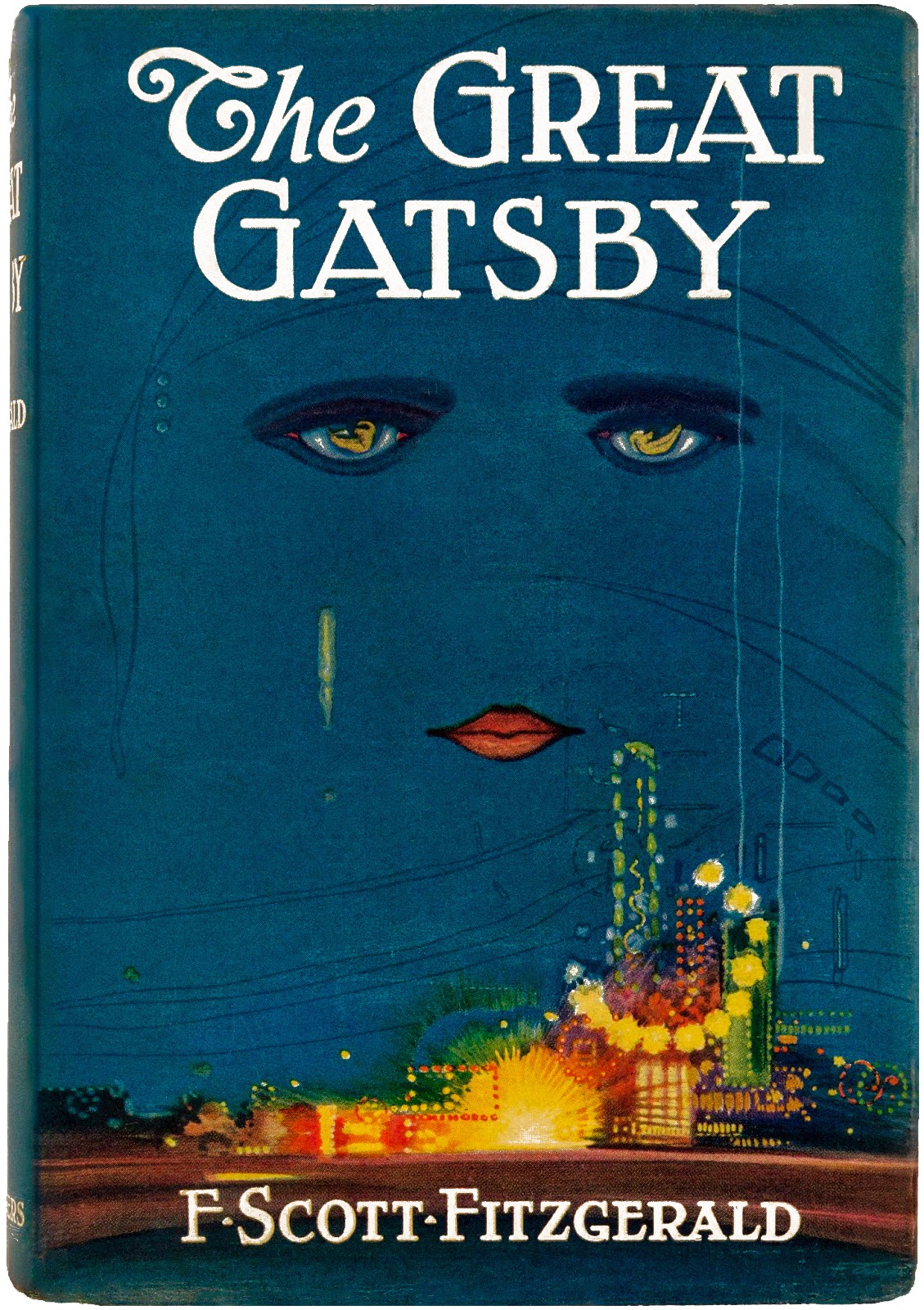

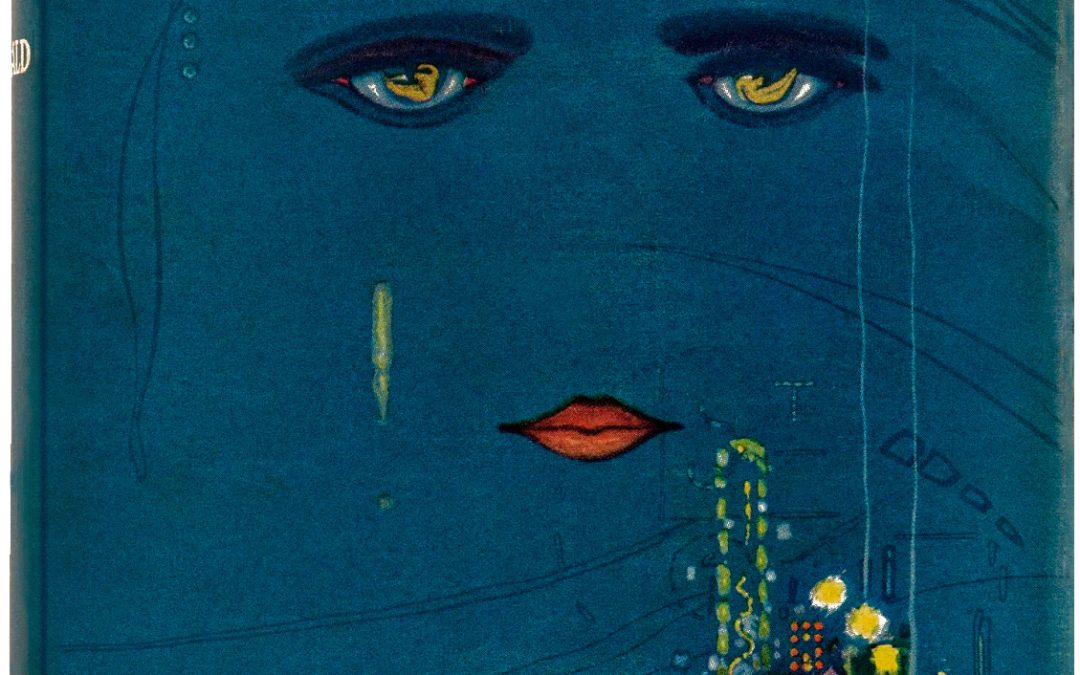

Wikipedia Image: The front dust jacket art with title against a dark sky. Beneath the title are lips and two eyes, looming over a city. Digitally restored and enhanced image of the first edition cover for F. Scott Fitzgerald’s novel The Great Gatsby (1925). Original cover illustration by Francis Cugat (1893–1981) and published by Charles Scribner’s Sons.

The historiography of American modernism draws out several important themes: the nature of the past between what we think is modern and what came before; and the romantic recurrent past where modernism is confusingly represented as realism, but, in truth, European Enlightenment (as 20th century modernism) never escaped its Romanic roots. Fitzgerald originally, as American modernism, proposed the question of time-past: can we re-grasp what has come before?

On the nature of the past:

“Can’t repeat the past?…Why of course you can!”

This is the cry of the romantic Jay, and his great dream of Daisy became his mental prison. There are matters which cannot be changed. Time past is the most significant. History, the story of the past, spirals rather than repeats; which is to say there is a pattern of never returning to the exact same point, but a similar point of the past, just some way forward. Things have to change.

On Life and Death in the Time-Past:

“Let us learn to show our friendship for a man when he is alive and not after he is dead.”

“Life starts all over again when it gets crisp in the fall.”

“So we drove on toward death through the cooling twilight.”

If there are any perennial finality, it is life and death. One lifetime. One death (most usually). Yet, as the romantic would have it, there are cyclic seasons. We can be born again, in a sense. Things do go around in a spiral, but finally, “So we drove on toward death through the cooling twilight.”

On the romantic recurrent past:

“And so with the sunshine and the great bursts of leaves growing on the trees, just as things grow in fast movies, I had that familiar conviction that life was beginning over again with the summer.”

“His heart beat faster and faster as Daisy’s white face came up to his own. He knew that when he kissed this girl, and forever wed his unutterable visions to her perishable breath, his mind would never romp again like the mind of God. So he waited, listening for a moment longer to the tuning fork that had been struck upon a star. Then he kissed her. At his lips’ touch she blossomed like a flower and the incarnation was complete.”

Fitzgerald is influenced by the Nietzschean ideal of history as recurrence. But then, again, the words, “his mind would never romp again like the mind of God”, is striking. The phrase “mind of God” is romantic and mysterious. There is a strong sense that the reference is beyond the human mind. The sensible hermeneutics would guide us to merely the idea that, in the end, in death, there is stationary nothing. In the romantic mind, in life, there is a rapturous moment when time does stand still. The search for meaning has ended, not in the thought, but in simply being (or non-being).

On the conclusion of American modernism:

“And as I sat there brooding on the old, unknown world, I thought of Gatsby’s wonder when he first picked out the green light at the end of Daisy’s dock. He had come a long way to this blue lawn, and his dream must have seemed so close that he could hardly fail to grasp it. He did not know that it was already behind him, somewhere back in that vast obscurity beyond the city, where the dark fields of the republic rolled on under the night.”

“Gatsby believed in the green light, the orgastic future that year by year recedes before us. It eluded us then, but that’s no matter—to-morrow we will run faster, stretch out our arms farther. . . . And one fine morning——

So we beat on, boats against the current, borne back ceaselessly into the past.”

Wikipedia Image: The Great Gatsby, a film directed by Baz Luhrmann, 2013 Poster. Image linked to Film Trailer.

While we are still alive we dream in a green light, something romantic. It can become a prison for the mind, if we are unaware in judgement, but Realism does not end the Ideal. How can we say what is real unless we prepared to reevaluate our hidden idealism.

*****

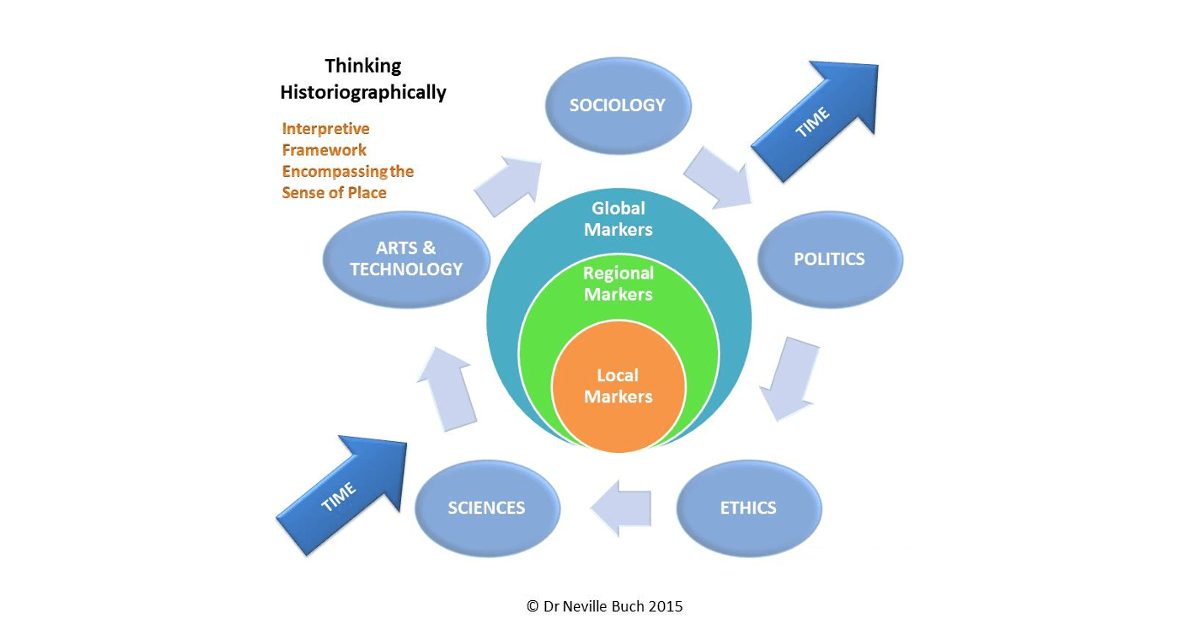

by Neville Buch | Apr 10, 2024 | American-Australian Relational History, Concepts in Educationalist Thought Series

https://www.chronicle.com/article/the-gutting-of-the-liberal-arts?utm_source=Iterable&utm_medium=email&utm_campaign=campaign_9519245_nl_Academe-Today_date_20240409&cid=at&sra=true

READ!!!! THINK!!!! ACT!!!!

David C.K. Curry, The Gutting of the Liberal Arts, The Chronicle of Higher Education,

APRIL 8, 2024

Let me spell this out to the Prime Minister, the Premier, the Government Ministers, and all elected representative officials at the three level of governments, and the manipulative-thinking bureaucrats, WE KNOW YOUR DIRTY SECRET.

It is, in fact, an open secret. There are types of personalities you hate, and that is not a too-stronger word.

“You can fool some of the people all of the time, and all of the people some of the time, but you can not fool all of the people all of the time.”

― Abraham Lincoln

David Curry’s article reveals this truth which publicly demands action. Curry states,

“The template is worth considering, even if it hasn’t yet reached your campus.”

What Curry is referring to are the intellectual cognition histories I have been discussing, on and off the university campuses in Australia. It is no surprise to those who have “eyes to see” and then take action on the visuals. One is reminded of the three monkeys of bureaucracy (the cognition histories in the present):

The three wise monkeys are a Japanese pictorial maxim, embodying the proverbial principle “see no evil, hear no evil, speak no evil”. The three monkeys are. Mizaru (見ざる), who sees no evil, covering his eyes. Kikazaru (聞かざる), who hears no evil, covering his ears. Iwazaru (言わざる), who speaks no evil, covering his mouth.

The concept of “realignments” from Curry is a significant case of this “bureaucracy”, or more accurately, the three monkey principle. Scholarly critics come along and demonstrate the critical alignment problems in governance, and the bureaucracy then manipulate a realignment solution which favours the those personal interests of governance against actually resolving the problem.

“The baneful results have included the loss of faculty members’ careers and livelihoods, the cheapening of students’ educations, and the transformation of institutions’ identities.”

It is an open secret. For decades, even as scholars as the apologetic appointees of the university governance, such as (selected examples)…

- Gregory, Helen (1987). Vivant Professores: Distinguished Members of the University of Queensland, 1910-1940, St. Lucia: University of Queensland Library;

- Grawe, Nathan D. (2021). The Agile College: How Institutions Successfully Navigate Demographic Changes, John Hopkins University Press;

- Story, John D. The Spirit of Caledonia in the Formation of the University of Queensland, Emmanuel College;

- Thomis, Malcolm I. (1985). A Place of Light & Learning: The University of Queensland’s first seventy-five years, St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press;

- Willetts, David (2017). A University Education, Oxford University Press…

…get it so wrong…the literature of which tells of this cognitive corruption, in universities, the federal and state government, and mirrored in local governance, is large and cannot be missed (selected examples)…

- Alexander, Fred. (1955). Sydney University And The W.E.A. (1913-1919). The Australian Quarterly, 27(4), 34-56. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/24477368;

- Aronowitz, Stanley and Henry A. Giroux (1991). Postmodern Education: Politics, Culture, and Social Criticism, University of Minnesota Press;

- Clark, William (2006). Academic Charisma and the Origins of the Research University, University of Chicago Press;

- Crotty, Martin (2018) Book Review: No End of a Lesson: Australia’s Unified National System of Higher Education / The Australian Idea of a University, Australian Historical Studies, 49:4, 566-568, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2018.1520081;

- Darian-Smith, Kate, and James Waghorne, (2019). The First World War, the Universities and the Professions in Australia 1914-1939. Melbourne University Publishing, Carlton, Victoria, Australia;

- Davis, Glyn (2011). The Boyer Lectures 2010: The Republic of Learning: Higher Education Transforms Australia, Bolinda Publishing;

- Davis, Glyn (2017). The Australian Idea of a University, Melbourne University Press;

- Edmonds, P. (2015). Whither the Universities. In Tilting at Windmills: The literary magazine in Australia, 1968-2012 (pp. 153-154). South Australia: University of Adelaide Press. Retrieved May 1, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/10.20851/j.ctt1sq5wf6.15;

- Emison, Mary (2013). Degrees for a New Generation: Marking the Melbourne Model, University of Melbourne Press;

- Fenn, J., Blandy, D., Arnold, T. J., Lorbach, J., Moore, S., Shepherd, J., & Silberman, L. (2015). Training Community-Engaged Culture Workers at a Public University. The Journal of American Folklore, 128(509), 351–368. https://doi.org/10.5406/jamerfolk.128.509.0351;

- Forsyth, Hannah (2014). A History of the Modern Australian University, New South Publishing;

- Forsyth, Hannah (2014) The Russel Ward case: Academic freedom in Australia during the Cold War, History Australia, 11:3, 31-52, DOI: 10.1080/14490854.2014.11668530;

- Ginn, Geoffrey (2009). ‘Cilento’s Centenary: The Triumph of His Topics’, Queensland Review, 16 (2), 57-72;

- Glanzer, P., Carpenter, J., & Lantinga, N. (2011). Looking for god in the university: Examining trends in Christian higher education. Higher Education, 61(6), 721-755. Retrieved April 28, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/41477837;

- Greenwood, Gordon (1954) The present state of history teaching and research in Australian universities: An estimate, Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand, 6:23, 324-338, DOI: 10.1080/10314615408595002;

- Harman, G. S., and Australian National University. Research School of Social Sciences. Education Research Unit. Research in the Politics of Education, 1973-1978 : an International Review and Bibliography / [by] Grant Harman. Education Research Unit, Research School of Social Sciences, A.N.U., 1979. State Library of NSW Offsite Storage collect 4pm next weekday T0243104;

- Hart, D. G. (1999). The University Gets Religion: Religious Studies in American Higher Education. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN: 0-8018-6210-8;

- Hayot, Eric (2021). Humanist Reason: A History, An Argument, A Plan, Columbia University Press;

- Henrick, Eureka and David Carment (2023). An ‘Important and Necessary Institution’: A History of the Australian Historical Association, The Australian Historical Association;

- Hill, Catharine B. , Winston, G., & Stephanie A. Boyd. (2005). Affordability: Family Incomes and Net Prices at Highly Selective Private Colleges and Universities. The Journal of Human Resources, 40(4), 769-790. Retrieved June 22, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/4129540;

- Giroux Henry A., and Stanley Aronowitz (1985). Education Under Siege: The Conservative, Liberal and Radical Debate Over Schooling, Routledge;

- Hutchinson, Mark and Bruce Mansfield (1992), Liberality of Opportunity: A History of Macquarie University 1964-1989, North Ryde: Hale & Iremonger;

- Jones, Steven (2022). Universities Under Fire: Hostile Discourses and Integrity Deficits in Higher Education, Palgrave Macmillan;

- Jones, Adrian (2011) Teaching History at University through Communities of Inquiry, Australian Historical Studies, 42:2, 168-193, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2010.531747;

- Kronman, Anthony T. (2007) Education End: Why Our Colleges and Universities have Given Up on the Meaning of Life, Yale University Press;

- Macintye, Stuart (2016). Life After Dawkins : The University of Melbourne in the Unified National System of Higher Education, Melbourne University Press;

- Macintyre, Stuart (2014) Book Review: Empire of Scholars: Universities, Networks and the British Academic World, 1850–1939, Australian Historical Studies, 45:1, 145-146, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2014.877795;

- Mandler, Peter (2020). The Crisis of the Meritocracy: Britain’s Transition to Mass Education since the Second World War, Oxford University Press;

- Marginson, Simon. (2016). The Dream Is Over: The Crisis of Clark Kerr’s California Idea of Higher Education. Oakland, California: University of California Press. Retrieved June 22, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/j.ctt1kc6k1p;

- Marginson, Simon (2016). Higher Education and the Common Good, Melbourne University Publishing;

- Marginson, Simon (1993). Education and Public Policy in Australia. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge [England] ; Melbourne;

- Mark, Young, (1900). A historical portrait of the new student Left at the University of Queensland : 1966-1972. Microfilm Services Brisbane, Brisbane;

- Murphy, Kate (2018) Book Review: From the Paddock to the Agora: Fifty Years of La Trobe University, Australian Historical Studies, 49:4, 569, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2018.1520104;

- Perry, B. (2011). Universities and Cities: Governance, Institutions and Mediation. Built Environment (1978-), 37(3), 244–259. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23290044;

- Pietsch, Tamson (2015). Empire of Scholars : Universities, Networks and the British Academic World, 1850-1939. Manchester University Press, Oxford;

- Pietsch, Tamson (2019) Book Reviews: Life After Dawkins: The University of Melbourne in the Unified National System of Higher Education / Coming of Age: Griffith University in the Unified National System / A New Kid on the Block: The University of South Australia in the Unified National System / Preserving the Past: The University of Sydney and the Unified National System of Higher Education, 1987–96, Australian Historical Studies, 50:1, 146-149, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2019.1559450;

- Rasmussen, Carolyn (2015) Book Review: A History of the Modern Australian University, Australian Historical Studies, 46:1, 151-52, DOI: 10.1080/1031461X.2015.992847;

- Reitter, Paul and Chad Wellmon (2021). Permanent Crisis: The Humanities in a Disenchanted Age, The University of Chicago Press;

- Roberts, Jon H. and James Turner (2000). The Sacred and the Secular University, with an Introduction by John F. Wilson. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN: 0-6910-1556-2;

- Salmon, J. H. M. (1962) European history in Australian Universities: Comments on Professor I. Schoffer’s article (Historical Studies, No. 37), Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand, 10:38, 222-223, DOI: 10.1080/10314616208595225;

- Schöffer, I. (1961) European history in Australian Universities, Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand, 10:37, 94-99, DOI: 10.1080/10314616108595210;

- Serle, Geoffrey (1971) A survey of honours graduates of the University of Melbourne school of history, 1937–1966, Historical Studies, 15:57, 43-58, DOI: 10.1080/10314617108595456;

- Shermer, Elizabeth (2021). Indentured Students : How Government-Guaranteed Loans Left Generations Drowning in College Debt, Harvard University Press;

- Taylor, Miles and Jill Pellow (2002). Utopian Universities : A Global History of the New Campuses of the 1960s, Bloomsbury Publishing PLC;

- Thomas, Amy, and Hannah Forsyth & Andrew G. Bonnell (2020) ‘The dice are loaded’: history, solidarity and precarity in Australian universities, History Australia, 17:1, 21-39, DOI: 10.1080/14490854.2020.1717350;

- Unnamed (1956) Research theses: Post‐graduate theses in history, political science, etc., held by Australian Universities, Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand, 7:27, 348-364, DOI: 10.1080/10314615608595077;

- Wright, Claire and Simon Ville (2018) The university tea room: informal public spaces as ideas incubators, History Australia, 15:2, 236-254, DOI: 10.1080/14490854.2018.1443701.

Yes, much of that critical literature is history and we must “out” the mad-brained “critic” who dismisses the history. AT THE VERY LEAST the corruption goes to an attitude of acceptance within the status quo, and dismiss any need for action which will change the policies which impoverished persons’ living, reduce university curriculum, and falsify the understanding of higher education: to quote, “the loss of faculty members’ careers and livelihoods, the cheapening of students’ educations, and the transformation of institutions’ identities.”

To conclude with a quote from Curry:

“The results are no accident….But who decides what the employment needs of the future will be, and which courses will be most relevant? In a humanizing moment, Smith teared up while announcing the cuts. While I have no doubt that her news was genuinely difficult to deliver, it was more difficult to receive.”

We wonder if the political decision-makers understand and if they really care?

Featured Image: Grunge Don T Be Stupid Stamp Seal and Bright Mesh Banker Gear Person with Light Spots. Illuminated polygonal net banker gear person icon with glare effect on a black background, and round Don T Be Stupid unclean seal print. Vector grid based on banker gear person icon. Illustration 236213769 © Evgeny Malkov | Dreamstime.com

by Neville Buch | Sep 8, 2022 | Article, Blog, Concepts in Educationalist Thought Series, Concepts in Public History for Marketplace Dialogue

Is ‘Schooling’ Education?

Or is it behaviour modification, and is it that necessarily a bad thing?

What I am suggesting is that the problem is not so much around the institutional commitment to modify behaviour for socialisation, but much, much, more that ‘schooling’ fails to produce comprehension in the educational needs and “outcomes.” Schooling has become performance, and, more exactly, performance measures, and much too often not true educational outcomes that each individual would consider important for their life values and career performance. This model(s) will continue to fail as long as governments, the markets, and the public echo chamber obsess with skills and job entry, rather than careers and true educative “outcomes.”

After a few millennials in the philosophy of education, since Aristotle, it is maddening that the political and bureaucratic dumb idols (idiots) cannot recognise this basic truth. A flourishing life is in lifelong learning (education), and never in a model of economic recovery or growth.

Unfortunately, the academic literature struggles to get to the point, but nevertheless, the scholarship constantly makes the point that 1) educational needs and outcomes are personal, 2) that policy needs to reflect that personalism (inclusively), and 3) the current ‘school’ models do not ‘perform’ in this way.

In 2015 Emily Milne and Janice Aurini calls for ‘discretionary spaces’ for parental involvement in ‘school policy’, but it raises questions, in the way Ivan Illich once raised the issue, whether being school policy that persons as parents or members of the community have ownership in the policy, or whether it is just another school performance measure.

There is a failure in policy-formulation to think critically in the philosophical terms of mission and purpose, always succumbing to the technological agenda. This is something Edward Rozycki thought about in 2015, in an article called “Mission and Vision in Education”. He wonderfully points out the ‘crap’ in ‘Vision statements’, ‘Mission statements’, and ‘Goal statements’. Rozycki calls it, “GIGO – garbage in, garbage out.” Here is the critical point of the personalism. If a student, as a person, is not enculturated with the autonomy of their own passions, education is impossible. Learning only sticks when there are passions to bind.

Mamphela Ramphele wonderfully brings this together in yet-another 2015 article, entitled, “Meaning and Mission”. The article starts with a quote from Viktor Frankl’s Man’s Search for Meaning (1946):

“Everyone has his own special vocation or mission in life; everyone must carry out a concrete assignment that demands fulfillment. Therein he [her/them?] cannot be replaced, nor can his [hers/theirs?] life be replaced, nor can his [hers/theirs?] life be repeated. Thus, everyone’s task is unique as is his [hers/theirs?] special opportunities to implement it.”

It is, as Mamphela Ramphele says, “the core of the pursuit of learning.” In a much earlier article Rozycki (1994) demonstrated the limits of schooling to perform in this way. Rozycki does not mince words, but offers plain-speaking. He said that if a person does not appreciate the function-mission distinction, you probably “have your canine anatomy all mixed up.” A reference to the very bad policy tail wagging the public educational dog. It is not a matter of being ‘dog brain’ but that there is an obsessive desire coming in the rear. Read this as ‘dirty’ as you like! Politeness, it seems, does not get the full attention of politicians and bureaucrats; when do they truly listen to the quiet scholarship?

There is much more literature that points to the same critiques of government and corporate gross misunderstanding of education. Elliot W. Eisner (1980) explained the relationships between artistic thinking, human intelligence and his understanding of mission of the school. The mission is a noble one, but, rooted in ancient classical philosophy, it is extremely difficult to see how modern schooling can deliver. Much of the philosophy of education literature points out that school missions are about socialisation (e.g., Thomas Bellamy and John Goodlad 2008, Nadine M. Finigan-Carr and Wendy E. Shaia 2018). And yet-again found in a 2015 article (results from an ad hoc JSTOR search), Linda A. Renzulli, Ashley B. Barr, and Maria Paino draws out the tensions between ‘specialist mimicry’ and ‘generalist assimilation’ through an examination of specialist charter school mission statements as “one indicator of innovation.” The article clearly infers – even as it was not the empirical intention of the research – that charter schools have succumb to the technological agenda (‘specialist mimicry’), and that “to foster innovation through specialisation”, at this obsessive level, destroys balanced ‘generalist assimilation’, and thus destroys education in Aristotelian terms (‘a flourishing life’).

This is why schooling fails as education. It is not per se behavioural modification for socialisation; that is merely a symptom of the technological agenda – the tail wagging the dog. Schooling fails because it is not addressing the personal needs nor the personal educative outcomes. The School addresses the mission of the school, an institution, and not a community of persons. The tail wags the dog. When will we stop this idiocy of this manufactured consent?

REFERENCES AND SOURCES

Bellamy, G. T., & Goodlad, J. I. (2008). Continuity and Change in the Pursuit of a Democratic Public Mission for Our Schools. The Phi Delta Kappan, 89(8), 565–571. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20442568

Bruno-Jofré, Rosa (2022). Ivan Illich Fifty Years Later: Situating Deschooling Society in His Intellectual and Personal Journey, University of Toronto Press

Eisner, E. W. (1980). Artistic Thinking, Human Intelligence and the Mission of the School. The High School Journal, 63(8), 326–334. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40365006

Finigan-Carr, N. M., & Shaia, W. E. (2018). School social workers as partners in the school mission. The Phi Delta Kappan, 99(7), 26–30. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26552377

Illich, Ivan (1971). Deschooling Society. London: Calder & Boyars.

Illich, Ivan (1973). Tools for Conviviality. New York: Harper & Row.

Illich, Ivan (1974). Energy and Equity. London: Calder & Boyars.

Illich, Ivan , et al (edited,1977). Disabling Professions. New York Marion Boyars

Macklin, Michael (1976). When Schools are Gone: A Projection of the Thought of Ivan Illich. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press.

Macklin, Michael (1975). Those Misconceptions are not Illich’s. Educational Theory, 25 (3), 323-329

Milne, E., & Aurini, J. (2015). Schools, Cultural Mobility and Social Reproduction: The Case of Progressive Discipline. The Canadian Journal of Sociology / Cahiers Canadiens de Sociologie, 40(1), 51–74. https://doi.org/10.2307/canajsocicahican.40.1.51

Ramphele, M. (2015). Meaning and Mission. European Journal of Education, 50(1), 10–13. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26609246

Renzulli, L. A., Barr, A. B., & Paino, M. (2015). Innovative Education? A Test of Specialist Mimicry or Generalist Assimilation in Trends in Charter School Specialization Over Time. Sociology of Education, 88(1), 83–102. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43186826

Rozycki, E. G. (1994). Mission versus Function: Limits to Schooling Aspiration. Educational Horizons, 72(4), 163–165. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42925069

Rozycki, E. G. (2004). Mission and Vision in Education. Educational Horizons, 82(2), 94–98. http://www.jstor.org/stable/42927135

Image: Collage of Images as (left to right, top to bottom):

Vision, education people concept – displeased red haired teenage student girl in glasses and checkered shirt l showing thumbs down over grey background. Photo 143161962 © Syda Productions | Dreamstime.com

Girl sleeping with holding a sign with the word Help. Photo 134669606 © Sevak Aramyan | Dreamstime.com

A close up shot of a little boy at school who looks distant and upset. Photo 57218706 © Liquoricelegs | Dreamstime.com

Grunge image of a stressed overworked man studying. Photo 39431170 © Kmiragaya | Dreamstime.com

Stressed college student for exam in classroom. Photo 68713779 © Tom Wang | Dreamstime.com

Worried young woman using laptop, teenager feeling nervous passing online exam or distance graduation test on web, f grade, anxious girl stressed by bad news in email, biting nails, looking at screen. Photo 101334378 © Fizkes | Dreamstime.com

*****

by Neville Buch | Nov 4, 2022

The 1990s Cultural Fall-Out for Teen Challenge Australia Inc. and the Associated Churches.

The argument of this history of Teen Challenge Inc. is that the organisation entered a difficult maturing phase of the 1990s. Much of the early twentieth-first century was a massive rebuild to recover from the challenges. The challenges were two, the State and the Society. Both had changed with the year 1989 as a clear marker.

Much credit in the years that followed goes to Alex Spencer, as Executive Director, Teen Challenge Inc., and Teen Challenge National Director and Queensland State Director from 1991 to 2000. There also new leadership of managers and directors. One example is Bob Engwicht. Bob Engwicht (manager of the residential services) who would move on to commence Teen Challenge in Tasmania. Engwich was responsible for the Tour De Freedom Bike Ride, the community workday implemented, and which was much more than a fundraising event. There were many more, and a few mentioned here.

The Program Operations Manager Craig Watson was appointed Manager of the New Life Centre, and Hebron House fell under Alanna Fraser to become a part of the Outreach division. Peter Sewell was the Outreach Regional Worker, based at Head Office, Teen Challenge Care (Qld) Ltd, in Mount Gravatt (P.O. Box 895, QLD 4122). Among others:

- Glen Schaefer, Outreach Coordinator, Teen Challenge Inc.

- Andrew Staggs, Manager, Accounting, Administrator & Training, Teen Challenge Inc.