Review Essay: Matthew Hunter, Charles Taylor’s Sublime Shortcomings: The great philosopher’s book about poetry is provocative but disappointing, The Chronicle of Higher Education, MAY 22, 2024.

Charles Taylor (2024). Cosmic Connections: Poetry in the Age of Disenchantment, Harvard University Press.

At a moment when, as Taylor has it, religiously inflected paradigms of thinking were being discarded — chief among them the belief that language could accurately reflect some divine order — Romantic poets and their heirs cultivated a language of what Taylor calls “reconnection,” a language which takes our “links with the cosmos” and makes them “palpable for you in a way which moves you and hence restores your link to them.”

At the heart of Taylor’s book is a story about language. Its animating question is, how we can believe in language’s power to do important and valuable things in the world when our words are no longer reflective of any divine order? The book’s guiding answer is that poetry demonstrates the capacity of language to establish “connections” that are otherwise impossible to come by. In the extensive readings that follow the book’s introductory chapters, Taylor shows how the poetry of Wordsworth, Hölderlin, Keats, Novalis, Shelley, Baudelaire, Hopkins, Rilke, Mallarmé, and T.S. Eliot puts readers in contact with experiences of divine harmony, of supernatural order, of a joy which is the direct result of a situated haecceity, which is to say, of the thisness of poetic experience. Language is not incidental to these experiences, but constitutive of them.

…

This impulse gives the book its bursts of real intellectual excitement. At a moment when literary criticism is still beholden to a historicism that treats the language of poetry as but another symptom of more general cultural conditions, Cosmic Connections dares to treat poetic language as a unique category of communication unto itself that is as distinct as it is elusive to the understanding. Elusiveness, for Taylor, is indeed part of the point of poetry. Whereas descriptive, declarative prose hinges on matters of fact, poetry — by dint of its reliance on figuration — elaborates a different kind of knowledge. “Figuring,” as Taylor has it, “can give insight, but it always leaves something more to be said, more about what features the object has and what it doesn’t. That is why it lacks the finality and clarity that ordinary prose can attain.”

Romanticism is one theme I have written on, and specifically, the connection between romanticism and politics.

I picked up the theme in my discussion in Conscious Existence: Realistic or Romantic? I make a claim for reality and I understand that such a claim is far too romantic. We grasp for what we individually want and it is always illusory; nevertheless, that becomes the reality of our situation. There are those behaviourists who claim that the mind, consciousness, self, is all illusion; pause and think, being all illusion makes it reality. It is the fact of the matter that the behaviourists have not awoken upon. I do not simply behave. I live. I live knowingly.

I am awake to my depressing reality. The realism, though, is that truth is in the measure. It is never that bad, that good, that ugly, that beautiful, and never that false or that true. It is measured upon an ideal horizon worldview, and the wider I make that view-in-learning the greater the hope I have. That is the insight – to embrace the depressing reality does not mean the end of hope. If we live then there is hope for further good, beauty, and truth. What it will make of you or I, cannot be said. It has to be lived. However, seeing the wide horizon worldview unfolding, that for me, is flourishing.

Romanticism is an analytic tool in my historiography. To quote, Lynn Hunt as President of the American Historical Association in May 2002:

It’s the difference of the past that renders it a proper subject for epic, romance, or tragedy-genres preferred by many readers and students of history. The “ironic” mode of much professional history writing just leaves them cold.

It is a work of tragedy with a plot around social taboo and a secret love affair which speaks about the idealism and romanticisation of the past. The continental Romantic Movement also had a teleology of liberalism. The cry of Jean-Jaques Rousseau, “Man was born free, and everywhere he is in chains” (L’hommes est né libre, et partou il est dans les fers), was a call for change where nationalist revolutionaries attempt to break out of the social imprisonment of the ancien régime. Rousseau had a different idea of change than most revolutionary progressives. He wanted humanity to return back to state of nature which he envisaged as a paradise of innocence.

Romanticism is a theme I explored in my review essay on The Great Gatsby. Before marrying Tom, Daisy had a romantic relationship with Gatsby. Her choice between Gatsby and Tom is one of the novel’s central conflicts. Fitzgerald’s romance and life-long obsession with Ginevra King inspired the character of Daisy. There is irony in Nick’s final judgement of Jay. Jay’s character had no scruples other than his romantic vision of Daisy as the “nice girl”. He was in the end revealed as the bootlegger in the crime network of ‘Wolfsheim’ who is based on New York gangster, Arnold Rothstein. One of the biggest shortfalls in American modernism of the 1920s, and 1930s, was the celebration of brutal crime and thuggish characters, as if there were no significant moral or ethical judgements; only aesthetical ones. Unfortunately, there is a swing back to this kind of nasty love of criminality in our own time. Swings and round-a-abouts. For example the Ned Kelly mythology is celebrated, and then it is correctly criticised. Against the romantic illusion, such criminals destroyed lives. The character of Jay Gatsby begins as an enigma, but, as his hidden life history is revealed, he is not so much careless or ruthless, but confused of mind. After his death, James’ father, Gatz senior, reveals a son who redeemed himself to the original family, making something of amends for his reckless ambition. His father had been given a house two years before Gatsby’s untimely end. Another aspect of the carelessness is the misjudgment that Nick’s father warned about. Tom had clearly set up George to murder Gatsby under the misjudgment of both Tom and George that it was Jay at the wheel of the vehicle that killed Myrtle. If Tom and George knew that it was Daisy, the judgement would have led in another direction. In the end, it is the capacity to revaluate our judgements that matters. As a good stoic, Nick’s father’s approach was to suspend judgement, but that is, realistically, a temporary position. It is only the romantic who fears disillusion who refuses the need for revaluation in judgement, which means that judgement has already been secured.

The historiography of American modernism draws out several important themes: the nature of the past between what we think is modern and what came before; and the romantic recurrent past where modernism is confusingly represented as realism, but, in truth, European Enlightenment (as 20th century modernism) never escaped its Romanic roots. Fitzgerald originally, as American modernism, proposed the question of time-past: can we re-grasp what has come before? Fitzgerald is influenced by the Nietzschean ideal of history as recurrence. But then, again, the words, “his mind would never romp again like the mind of God”, is striking. The phrase “mind of God” is romantic and mysterious. There is a strong sense that the reference is beyond the human mind. The sensible hermeneutics would guide us to merely the idea that, in the end, in death, there is stationary nothing. In the romantic mind, in life, there is a rapturous moment when time does stand still. The search for meaning has ended, not in the thought, but in simply being (or non-being).

While we are still alive we dream in a green light, something romantic. It can become a prison for the mind, if we are unaware in judgement, but Realism does not end the Ideal. How can we say what is real unless we prepared to reevaluate our hidden idealism.

In that hidden idealism is the understanding that the Romantic is the heart of local studies. To quote W.G. Hoskins’ “English Provincial Towns in the Early Sixteenth Century” (Transactions of the Royal Historical Society, Fifth Series, Vol. 6 (1956), pp. 1-19):

The English historians have concentrated almost exclusively upon the constitutional and legal aspects of town development. They have concerned themselves with the borough rather than the town, with legal concepts rather than topography or social history, just as the agrarian historians have been pre- occupied with the manor rather than the village. Local historians of towns and villages have, with two or three notable exceptions, followed suit in this ill-balanced emphasis. The result is that we know surprisingly little about the economy, social structure, and physical growth of English towns before the latter part of the eighteenth century.

The context of the early sixteenth century might appear to have little relevance, but the themes of urban development and its social impact on the human experience is the same for late nineteenth and and early twentieth century Brisbane local history, albeit keeping in mind very distinctive differences between the political system of the different centuries. It must be borne in mind that the late nineteenth century was obsessed with medieval romanticism, and the questions of what historians of the era called the “Agrarian Revolution” spoke to the loss felt in the Romantic Movement.

Dr Rod Fisher, an historian at the University of Queensland in 1980s and 1990s, pioneered academic-based local history in the former Centre of Applied History. Fisher was also a specialist in Tutor and Stuart History, and thus, represented the British model of bridging sixteenth and seventh century English history with contemporary local history. The challenge for the reader is to apply the type of analysis Hoskins demonstrated for sixteenth century England in local history of late nineteenth and twentieth century Queensland.

An example is the work I did in the History of Teen Challenge Inc. In Essay 3 — The Spirit (1967-1975): The early mission and Reformed Theology of Charles Ringma, I wrote:

The revolutionary feature was the motifs of the youth counterculture in the German and French Romantic traditions: coffee shops of radical thought in seedily intercity districts of student habitations. In March 1968, [Arthur] Blessitt had opened a coffee house called ‘His Place’ in a rented building next door to a topless go-go club. Ann Wilkerson had much earlier organised the first coffee houses of the Teen Challenge movement.

This is an understanding that many local historians miss, and, indeed, most Australian historians miss the thinking, since the collapse of the intellectual history ‘industry’, most thanks to the idiocy (think Dostoevsky) of the neo-liberal economy.

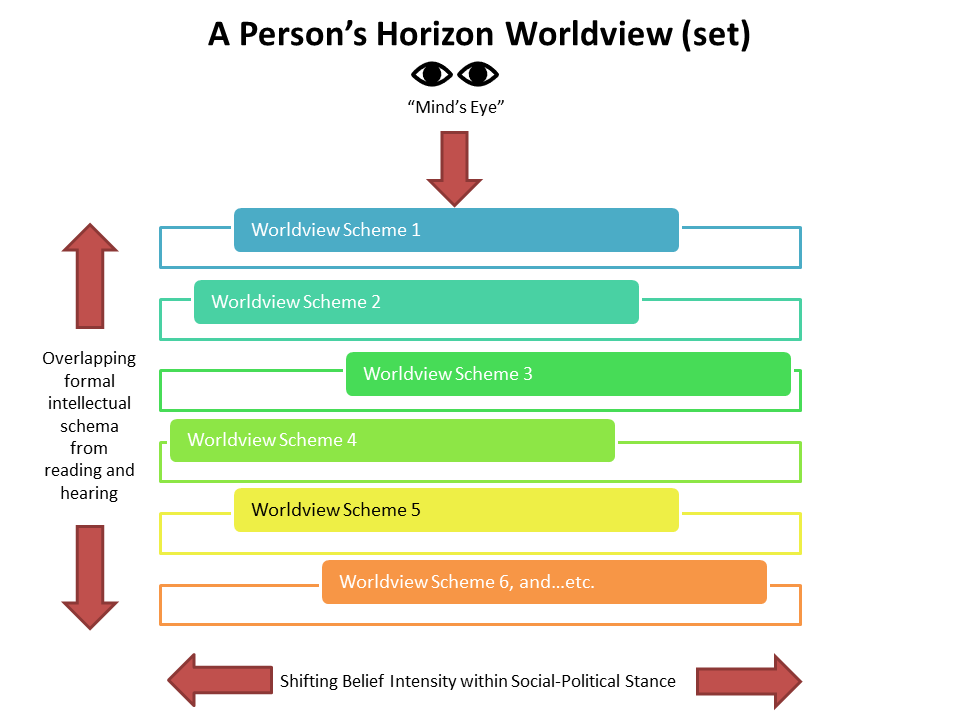

Featured Image: 01. Mind’s Eye of a Personal Horizon Worldview

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- Dear grossly, ethically, corrupted - December 21, 2024

- Thoughts with a Professional History colleague on “Artificial Intelligence” - December 21, 2024

- Stephanie M. Lee on “AI by omission”, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Thursday, December 19, 2024 - December 20, 2024