This is a blog post to set everyone straight, which makes me open to the critique of being one of Manning Clark’s ‘straighteners’; but that’s another story. My arguments, as a general framework, is based on a basic critique of the neo-conservative paradigm. The paradigm is a defence of a cultural position(s) which has become implausible in the last 70 years, since the early days in the ‘neo-con’ writings of people like William F. Buckley (Virginia, USA) and Frederick Charles Schwarz (Queensland, AU). My critique of this positioning goes to both culture and religion.

Recently, I was gobsmacked by the language and phrasing of a cultural warrior in a ‘Facebook’ community of social justice. Such posts are not clear-thinking scholarship. It is polemics which is not prepared to cite the exact scholarly books on the questions at hand. The descriptions offered are no better than the nonsense on Fox News, Sky After Dark, and, from-time-to-time, in the Murdoch Press.

So, to explain from my 1995 thesis:

Queensland political culture did not escape from the American influences on Queensland Protestantism. This was seen in the populist politics exploited by the National Party Government [1968-1989], which encouraged American-style right-wing fundamentalist political lobby groups. In the late 1980s, when the National Party Government was in crisis the Christian neo-conservatives supported it openly in an attempt to keep their power base. The downfall of the National Party Government at the 1989 elections has meant the demise of many political lobby groups, but it has not meant the end of American style populist politics in Queensland. [Preamble: 2]

During the mid-1970s, a power struggle emerged within the [Southern Baptist] Convention’s hierarchy between the progressive elements of the Convention and neo-conservative fundamentalists. This struggle resulted in fundamentalists taking over executive positions, creating an uneasy co-existence between the two [Hudsonian] political blocs. [Chapter 1: 24; from Winthrop Hudson. American Protestantism. University of Chicago. 1961. p. 165. In the light of this phenomenal growth, Hudson defines the Southern Baptist Convention, along with the Lutheran Church-Missouri Synod, as the “growing edge of protestantism”, a middle group as “co-operative protestantism” (liberal or “progressive” denominations). These are church bodies that have been active in the ecumenical movement and are affiliated with the American National Council of Churches (N.C.C.). The other section is what Henry Pitt Van Dusen describes as the “Third Force” Protestantism; the miscellaneous threefold grouping of adventist, fundamentalist, and holiness churches]

The Australian encounter with the American revivalism has come in three distinct, but interrelated, sub-species of the American revivalist tradition, Classic fundamentalism, Neo-evangelicalism, and Pentecostalism. Although internationally present, these conservative religious systems are, in their essence, a reflection of the American Protestant culture. [Chapter 2: 60]

The [other] expressions of American Neo-Calvinism [within American fundamentalism] also found their way to Queensland. Francis A. Schaeffer was a popular apologist for the Queensland evangelical community in the 1970s and 1980s. Schaeffer had been influenced by Cornelius Van Til, a professor of apologetics (1930-1975) at Westminster Theological Seminary. Van Til had devised a system of Presuppositionalism, a philosophy which divides all knowledge down to either one of two presuppositional beliefs, the bible held as the infallible Word of God, and all other views. Schaeffer sought to demonstrate that all areas of secular learning which departed from the worldview of the Protestant Reformation were based on the latter category, and therefore, were all in error. For Schaeffer, the standard of true learning had been established at the Reformation, and all areas of Western culture had since passed over “the line of despair” (despair at failing to find certainty and absolutes, which in Schaeffer’s opinion, lay only in the Bible). In his scholarly endeavours, Schaeffer was assisted by a number of European colleagues, English scholars Os Guinness and Jerram Barrs, Dutch philosopher Herman Dooyeweerd, and Swiss scholar Udo Middelman, and so established two “intellectual” communities, called L’Abri, in England and Switzerland (where he resided). Schaeffer’s writings, however, continued to be published and largely supported within the American evangelical community. [Chapter 2: 73-74]

The influence of American Neo-Pentecostalism has also extended out to para-church organisations. In 1974, He Lives ministry, led by Jack and Swanny Kooy, set up a conference centre in Beenleigh. By 1982, the ministry included a Christian primary school and a printery. The Covenant Evangelical Church, the ministry arm of the Logos Foundation, was started in 1969 by the New Zealand Charismatic Baptist minister Howard Carter. The Church moved with the Foundation from the Blue Mountains to Toowoomba in the mid-1980s. The Foundation has modelled the neo-conservative political activity of the large American Neo-Pentecostal church organisations, and was active in Queensland state politics during the last years of the Bjelke-Petersen government. [Chapter 2: 101]

[YWAM, Loren] Cunningham was deeply affected by the Cold War mentality that pervaded the American neo-conservative Christian community, of which he was apart. He lined up politically with the New Christian Right in the 1980s, along with Bill Bright, Pat Robertson, and Tim Lahaye. [Source, Gifford. The Religious Right in South Africa. p. 55. Chapter 6: 293, fn. 114]

Towards the end of 1977, the Baptist Union took up the issue of independent Christian schooling. The Department of Youth and Christian Education (DYCE) put the question of adopting independent Christian schools to the Union by surveying 52 Baptist churches and inviting individual submissions (50 submissions were forthcoming). One of the most important submissions was made by Rev. Norman E. Weston. Weston’s submission called for the establishment of independent Christian schools along the same lines outlined by the American neo-conservatives. Weston argued that humanistic philosophy formed the background to the present secular education system in Queensland. [a very bad thing in Weston’s and the American ‘neo-con’ views; Chapter 10: 413]

Under the Bjekle-Petersen administration, American-style right-wing fundamentalist political lobby groups flourished. The most significant groups were the Christian Anti-Communist Crusade, the Committed Christian Crusade, Society To Outlaw Pornography & Committee Against Regressive Education, Creation Science Foundation, Women Who Want to be Women, The Council for A Free Australia, League of Rights, Logos Foundation, Ten Thousand Men, and the National Alliance for Christian Leadership. One of the oldest groups, which has taken different forms, has been the Queensland League for National Welfare and Decency, established in 1964. In 1973, the League became the Community Standards Organisation, and in 1980, the Festival of Light and the Community Standard Organisation amalgamated to become the Festival of Light – Community Standard Organisation (FOLCSO), Queensland. All these groups were modelled on the American Far Right of the 1960s, and the American New Christian Right of the 1980s. [Chapter 11: 425-426]

A significant development in the influence of the American Christian Far Right in Australia was the establishment of the Australian Christian Anti-Communist Crusade (CACC). The CACC was founded by Dr. Fred Schwarz in the United States in 1953. Interestingly, Schwarz was a medical doctor from Brisbane, and a Queensland Baptist lay preacher. Schwarz toured the United States, claiming that the communists had planned to takeover that country in 1972. In 1954, the CACC was established in Australia with its headquarters in Concord, New South Wales, and a Queensland office in Ferny Grove. In the mid-1960s, the CACC showed American anti-communists films in Brisbane. Schwarz’s book You Can Trust the Communists was sent to clergymen and to every parliamentarian in Australia. In September 1962, the Queensland Baptist gave Fred Schwarz’s book, You Can Trust The Communists – To Be Communists, glowing praise. The reviewer stated that Schwarz’s book “is one every freedom-loving thinker should read and re-read”. Advertisement for the CACC appeared in both the Queensland Baptist and the Methodist Times throughout the 1960s. The advertisement was headed “Will Communism Conquer Australia before 1972 ?” or simply “Will Communism Conquer Australia ?”. [Chapter 11: 428-429]

Conspiratorial groups continued to thrive in Queensland. In late 1981, writing for the Queensland Baptist Rev. Ron Bickerston of the Baptist Social Justice Forum caused a reaction from Christian neo-conservatives when he made a comparison between the Russian invasion of Afghanistan and the colonial invasion of Australia. G.S. Baker of Wondai suggested that such comments were part of the racial upheaval which was “Satan’s work, preparing for world government (Anti-Christ)”. [Chapter 11: 435]

The appearance of [Hughie] Giesbert’s letter [in Queensland Baptist] reveals that the minority position of the American old Christian far right was still active in Queensland churches like the Baptist Union in the mid-1980s, a time when the New Christian Right (a resurgence of the American old Christian Far Right but politically focused on more “reasoned” rhetoric) had already emerged. [Chapter 11: 438]

The 1970s saw the rise of the New Christian Right in the United States with such groups as Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, Christian Voice, and Ed McAteer’s Religious Roundtable [Chapter 11: 438-439]

In 1983, the Christian neo-conservative organisation, Women Who Want to be Women, linked to the Festival of Light network, carried out a major political campaign against the Australian ratification of the United Nations Convention Against All Sexual Discrimination. The campaign had been particularly successful in being able to disseminate American right-wing conspiratorial theories which attempted to link the meaning of the Convention to a plot to undermine Australian sovereignty. [Chapter 11: 436]

The Christian neo-conservatives became very “vocal” in the pages of the Queensland Baptist when Steven Westbrook of Toowong claimed that much of the criticism of the Convention within the Baptist Union “demonstrates a lack of historical and anthropological awareness”. Queenie Kilpatrick of St. George claimed that the Convention would see the State taking over welfare of the child from parents, and that government welfare officers in Scandinavia, and even in South Australia, were seeking to take children from their parents. Jackie Butler, State Coordinator of Women Who Want to be Women, claimed that “Our children will be managed, controlled and circumscribed by Canberra politicians and bureaucrats, to an extent thought impossible only 20 years ago”. [Chapter 11: 436-437]

The first indication of the influence of the American New Christian Right in Queensland was the campaign against the introduction of Social Education Materials Project (SEMP) and Man: A Course of Study (MACOS) in Queensland schools. The main ideological objection to SEMP and MACOS was the Christian neo-conservative belief about “humanism” as a force that was undermining Christian values. Dr. Rupert Goodman, Reader in Education at the University of Queensland, lectured on his view of the “humanist” threat in the educational system at the Festival of Light organised “Humanism In Education” Conference at Macquarie University in July 1980. [Chapter 11: 439; Source on the ideological linkages, Robert C. Liebman and Robert Wuthnow (Editors). The New Christian Right. Mobilization and Legitimation. New York. Aldine Publishing Company. 1983.]

Other New Christian Right organisations emerged in Queensland. In 1984, Jackie Butler, Queensland Coordinator of Woman Who Want To Be Women, and a member of Wynnum Baptist Church, began The Council for A Free Australia, described as “Pro-Christian, Pro-Family, Pro-Free Enterprise, Pro-Freedom, Pro-Life, Pro-Common Law”. [Chapter 11: 442]

In the late 1980s, the National Party Government was in crisis. Christian neo-conservative groups were increasingly alarmed at the prospect of losing a sympathetic administration. A number of Queensland Protestant churches publicly came out in support of Premier Joh Bjelke-Petersen. Two of Brisbane’s largest churches, located in the Mount Gravatt-Mansfield bible belt, Christian Outreach Centre and Garden City Christian Church, were outspoken supporters. This support was generated by the National Party Member for Mount Gravatt and a member of Garden City Christian Church, Ian Henderson. Henderson served in the National Party Government as the Minister for Justice and Minister for Corrective Services. In 1986, Joh Bjelke-Petersen appeared on the platform of Garden City Christian Church the Sunday before he announced the next parliamentary election which he won with the support of the “church vote”. Increasingly in the late 1980s Bjelke-Petersen was politically supported by new emerging Christian neo-conservative organisations, such as Ten Thousand Men, and the Logos Foundation. Ten Thousand Men was an organisation that called men to pray for Australia’s political leaders, but its prayer points were always phrased for outcomes that were in favour of a neo-conservative agenda (such as the defeat of the referendum on the Bill of Rights). Leaders with left-wing views were targeted as those who were in need in prayer, and the organisation celebrated as God’s answers to prayer when Lionel Murphy retired from the High Court, Neville Warn retired as Premier of New South Wales, and Don Chipp retired as leader of the Australian Democrats. Those leaders with strong right-wing views were never targeted in the same manner. The Ten Thousand Men was one of the primary organisations interlinked with the neo-conservative National Alliance for Christian Leadership involved in setting up the bicentenary Christian National gathering in Canberra. The operation of the National Alliance for Christian Leadership was very similar to the American Christian neo-conservative groups, such as the Religious Roundtable. In 1988, the Logos Foundation and the National Alliance for Christian Leadership ran a No campaign in the 1988 Referendum because they believed that a United Nations conspiracy for a one world dictatorship was behind the proposed Bill of Rights. [Chapter 11: 443-445]

MORE RECENT SOURCES

Buccola, Nicholas (2019). The Fire is Upon Us: James Baldwin, William F. Buckley Jr., and the Debate over Race in America, Princeton University Press.

Johnson, C. (2005). Narratives of Identity: Denying Empathy in Conservative Discourses on Race, Class, and Sexuality, Theory and Society, 34(1), 37-61. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/4501713

Jones, Steven (2022). Universities Under Fire: Hostile Discourses and Integrity Deficits in Higher Education, Palgrave Macmillan.

Taylor, Tony (2013) Neoconservative Progressivism, Knowledgeable Ignorance and the Origins of the Next History War, History Australia, 10:2, 227-240, DOI: 10.1080/14490854.2013.11668469

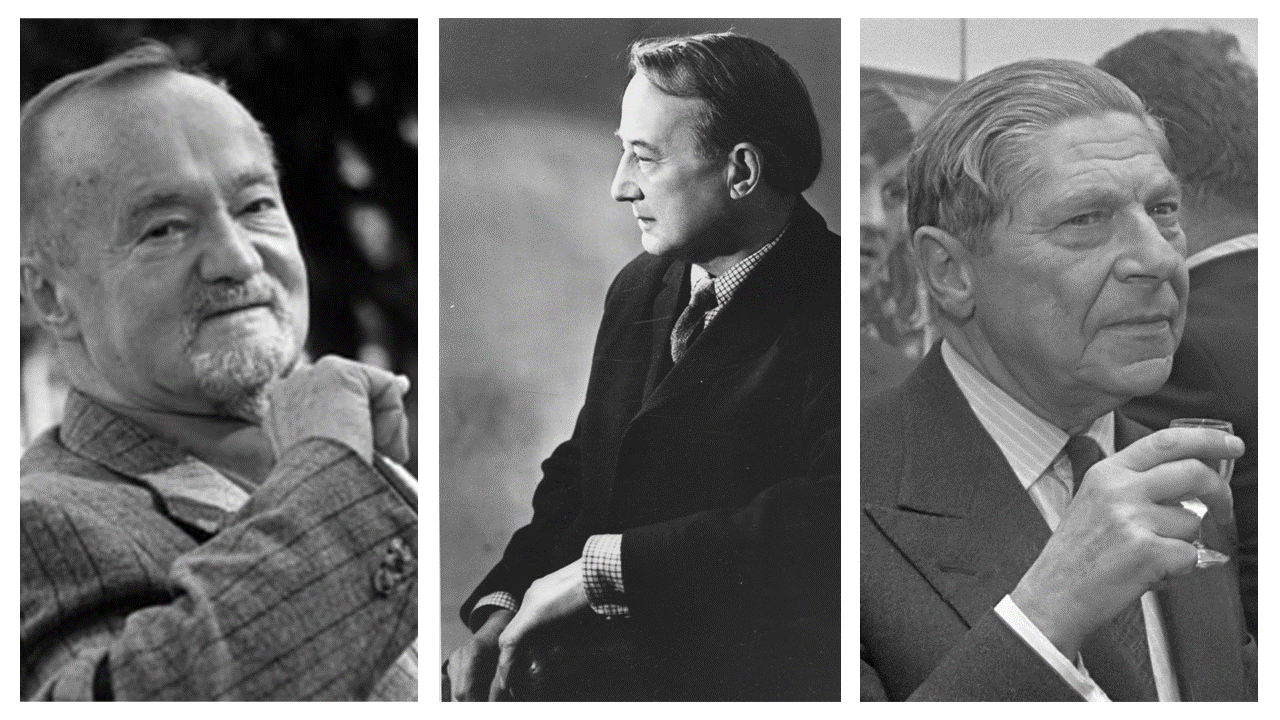

Image: Toulim, Oakeshott, Koestler, conservative thinkers who are not ‘neo-cons’ in the American semantic, and whose works (sources) are the great critiques of American neoconservatism.

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- Dear grossly, ethically, corrupted - December 21, 2024

- Thoughts with a Professional History colleague on “Artificial Intelligence” - December 21, 2024

- Stephanie M. Lee on “AI by omission”, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Thursday, December 19, 2024 - December 20, 2024

Just to set a detail straight… He Lives set up a school prior to 1982 and it was in Carbrook not Beenleigh… I know this because I lived in Jack and Swanny Kooys commune and attended the school which my father pioneered to protect us from the evil of the worldly system.

Thank you, Geraldine, for the detail. Details are important but the current issue being discussed by evangelical historians is that the outlook in the folkish historiography “cannot see the forest for the individual trees.” The thinking of “the evil of the worldly system” is too homogeneous, as if the forest has no variation in perspective than what bounces off the inside of the cognitive bubble. This affects everyone, but we can move beyond the bubble by being empathetic in our thinking, by considering “the other” deeply. See Emmanuel Levinas, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Emmanuel_Levinas