by Neville Buch | Jun 7, 2023 | Article, Blog, Concepts in Public History for Marketplace Dialogue, Concepts in Religious Thought Series

Image: An image of Francis Schaeffer, http://www.pcahistory.org/images/schaeffer01.jpg on the Wikipedia entry site.

INTRODUCTION

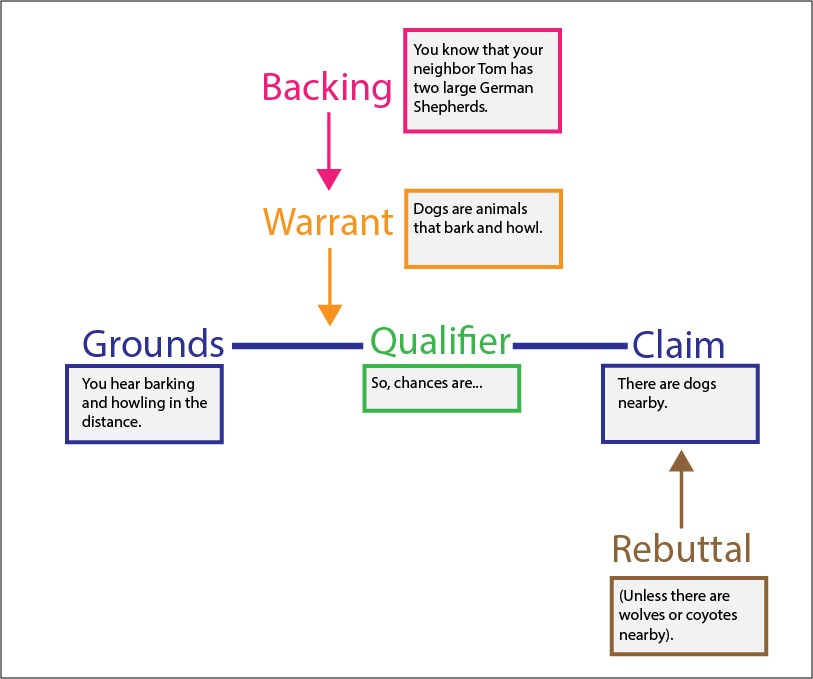

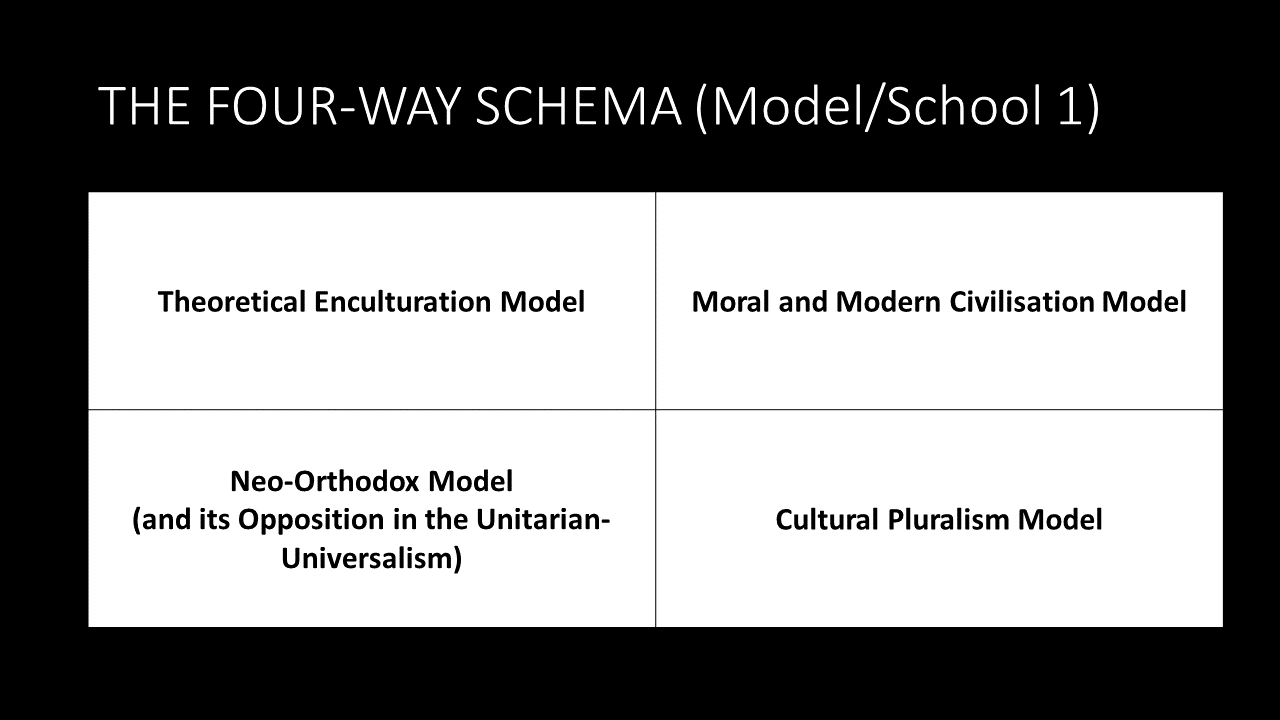

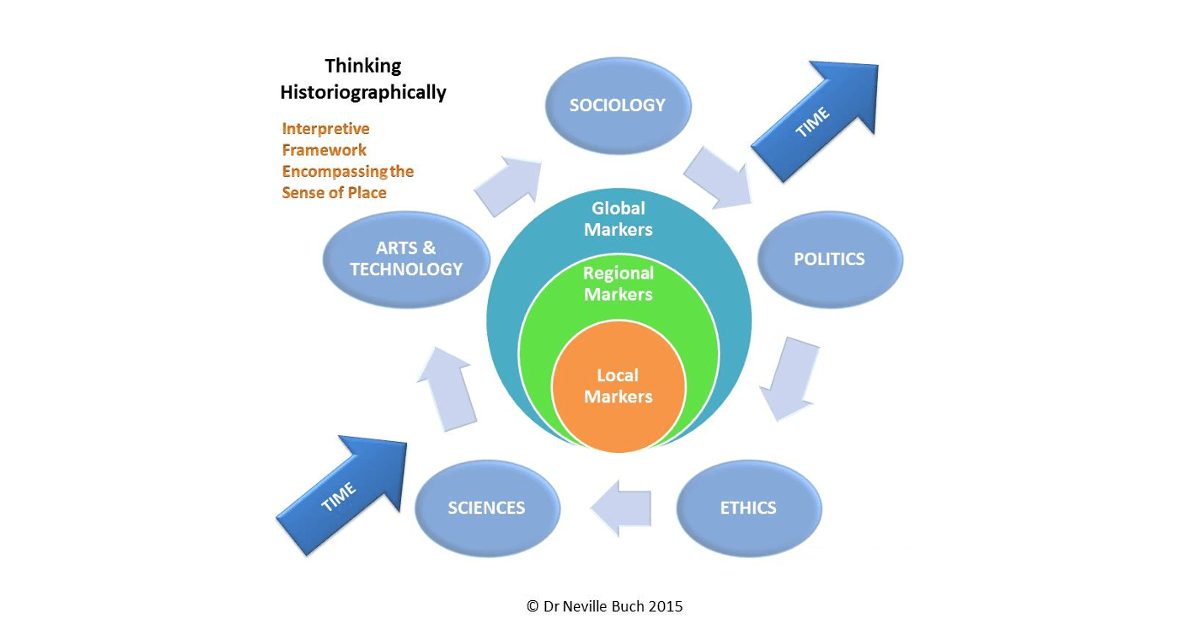

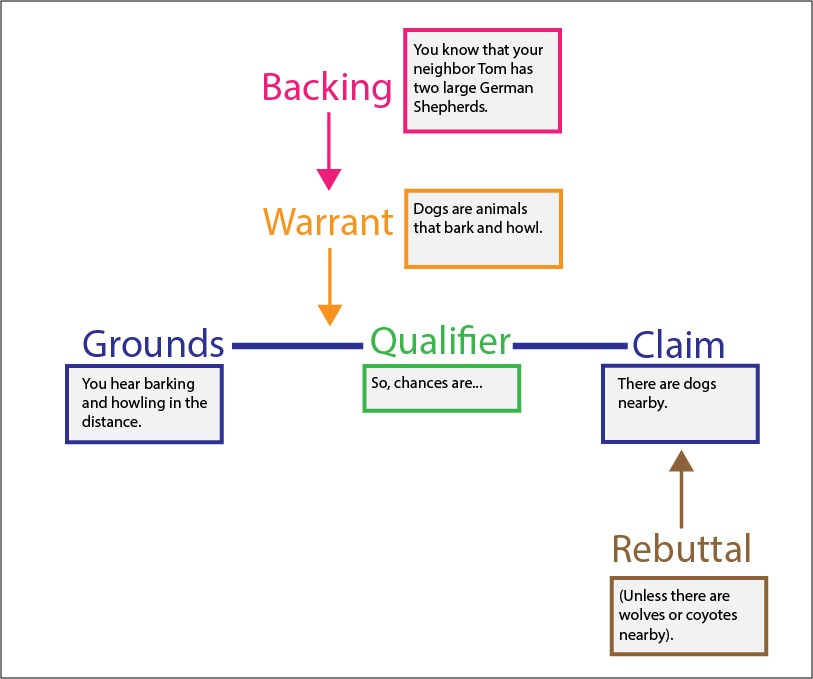

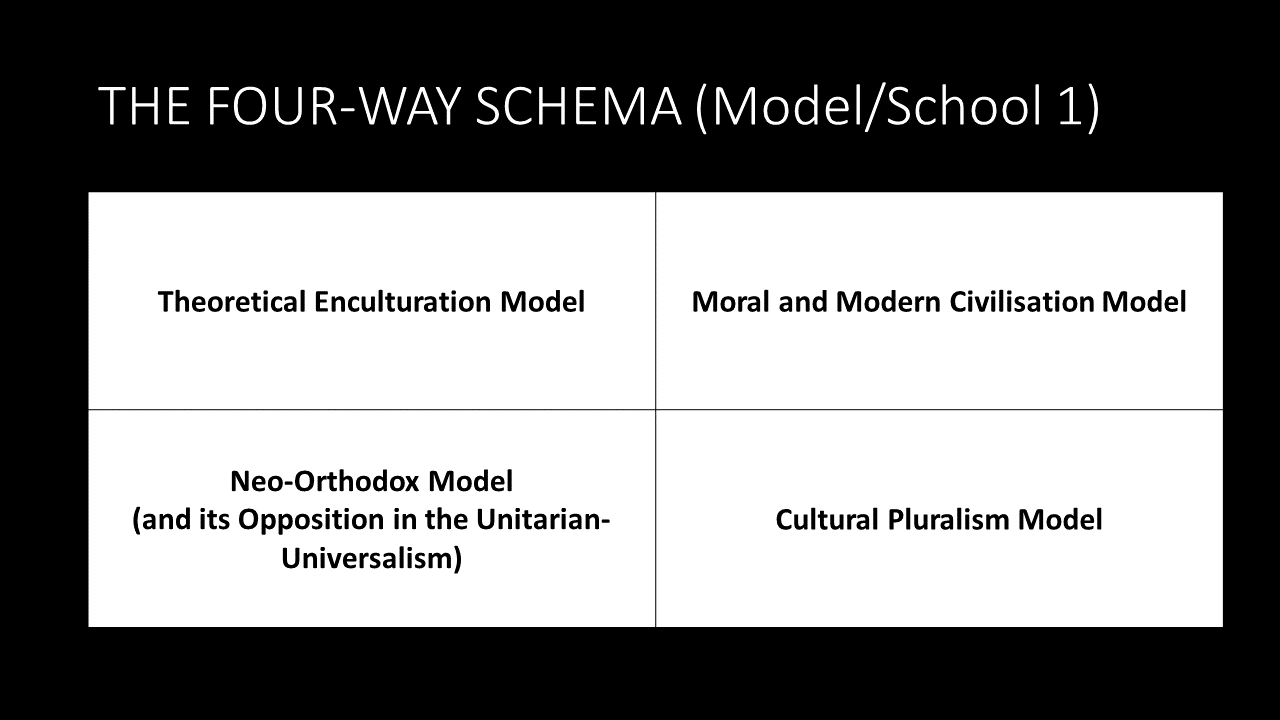

James Fodor, Unreasonable Faith: How William Lane Craig Overstates the Case for Christianity (Hypatia Press, 2018) is a very generous critique towards the Christian apologist. Foder is making the argument for me on how apologetics completely miss the wider disciplinary critiques. For Fodor and me, faith is not the target, but an in-principle argument that apologetics does not achieve what it seeks to accomplish: a convincing argument for the knowledgeable non-believer. In Fodor’s case he takes the best case of Christian Apologetics in William Lane Craig, and as the book title states, demonstrates it has not made the case for Christianity. Foder often shows that this because many of the arguments are not on historical Christianity per se, but rather presents other related targets for skeptics; arguments which are fallaciously abusive in exclusivist claims for faith. The abuse (for me as I interpret the arguments, not necessarily as Fodor’s specific references) is the cherry-picking of apologetics and taking the claims away from the context of wider scholarly debates in history, sociology, philosophy, and other disciplines. What students of apologetics failed to be taught are that apologetic arguments commonly misunderstands comprehensive fields of knowledge as scholars understand them today. Against common sense prejudice, the advocates in the disciplines of knowledge have not decided that it is a free catch-bag in the way apologetics works. Apologetics, if it is a field of knowledge, is rhetoric: the field which teaches tricks of defeating an opponent in an argument without regard to the complexity of truth (propositional knowledge). This is not education, and it is not learning in faith.

This blog article is part of a series in argument that demonstrates that Apologetics does not establish a convincing case for Christian faith, and the only solution for evangelicals is to engage in the disciplines proper. It should be noted that there are already theists/Christians who are doing just that and reject the apologetics pathway. In principle, Apologetics places defence before an open questioning of faith, and continually defers to “orthodoxy imitation” (as a characteristic in the social psychology). This is not education and does not mean a necessary abandonment of faith. All that is expected in the argument is the continual challenging of the disciplinary reasoning with the multi-layering of multi-disciplinary thinking. In that process there is a place for the traditional concept of “the apology” within disciplinary discourses, but it is very different to the practice of modern apologetics.

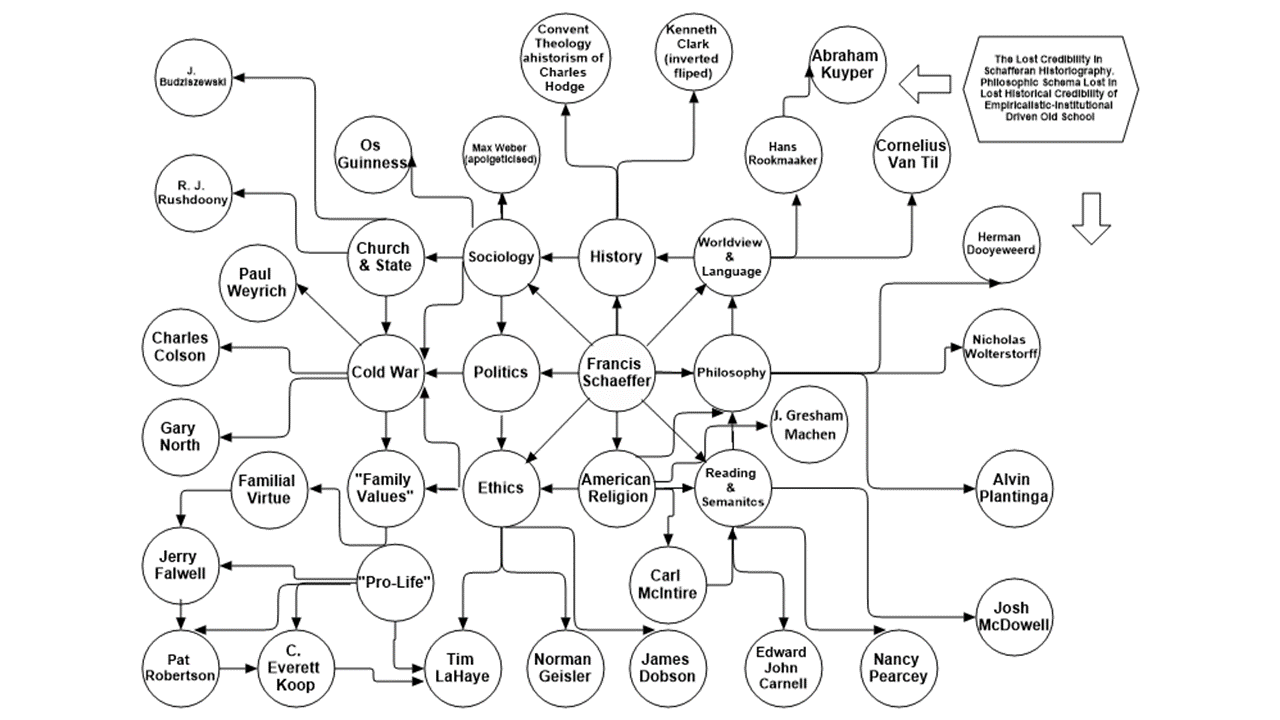

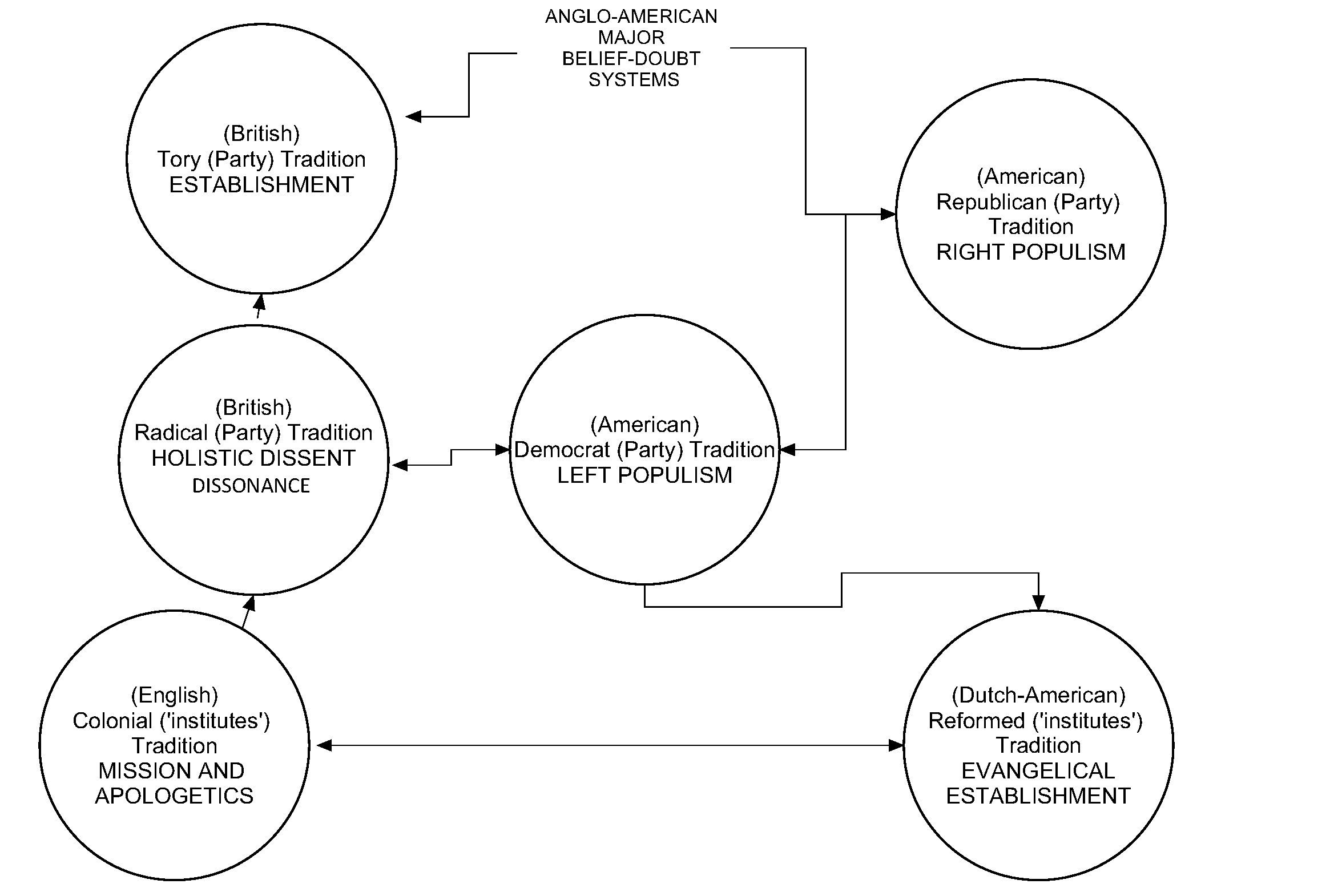

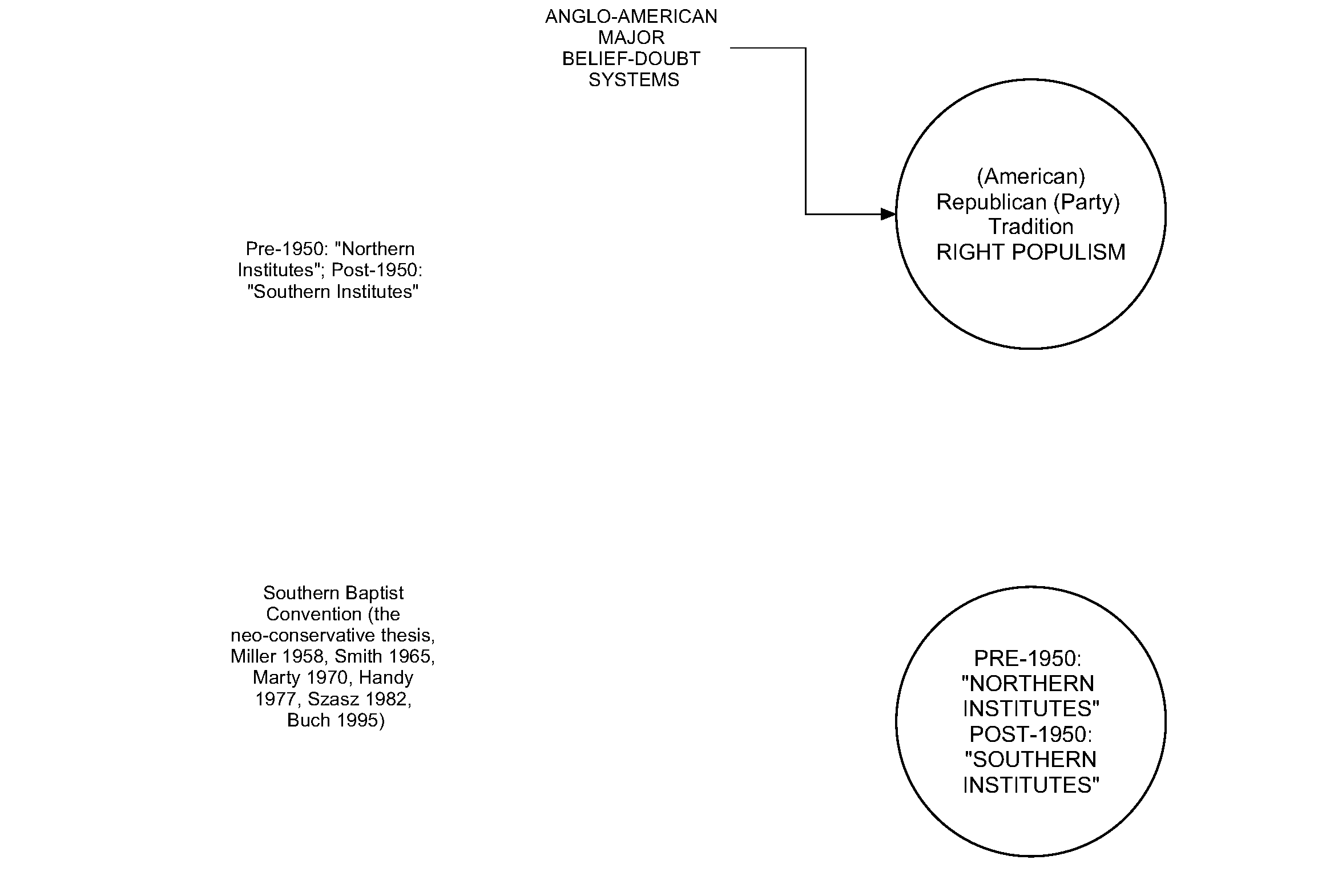

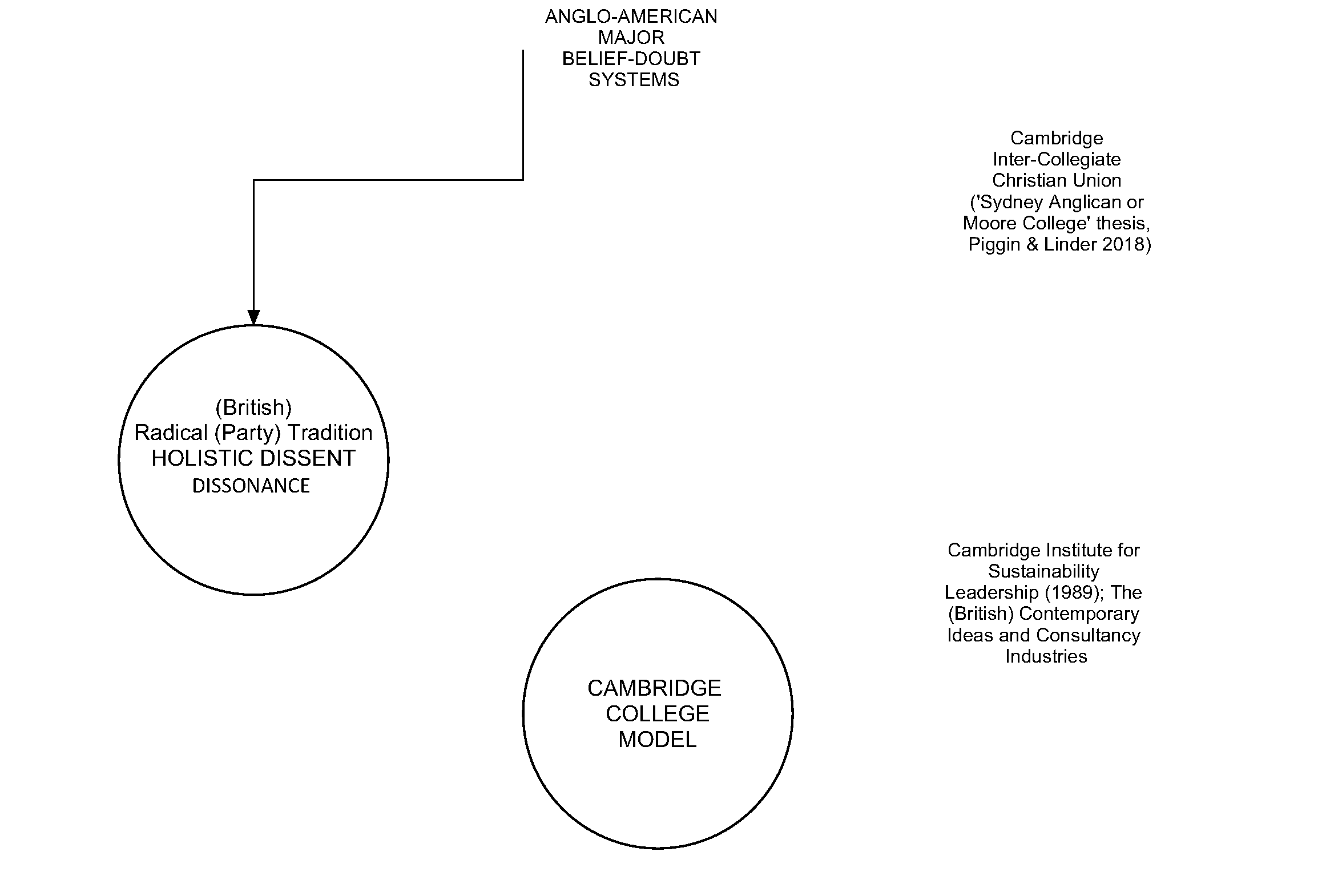

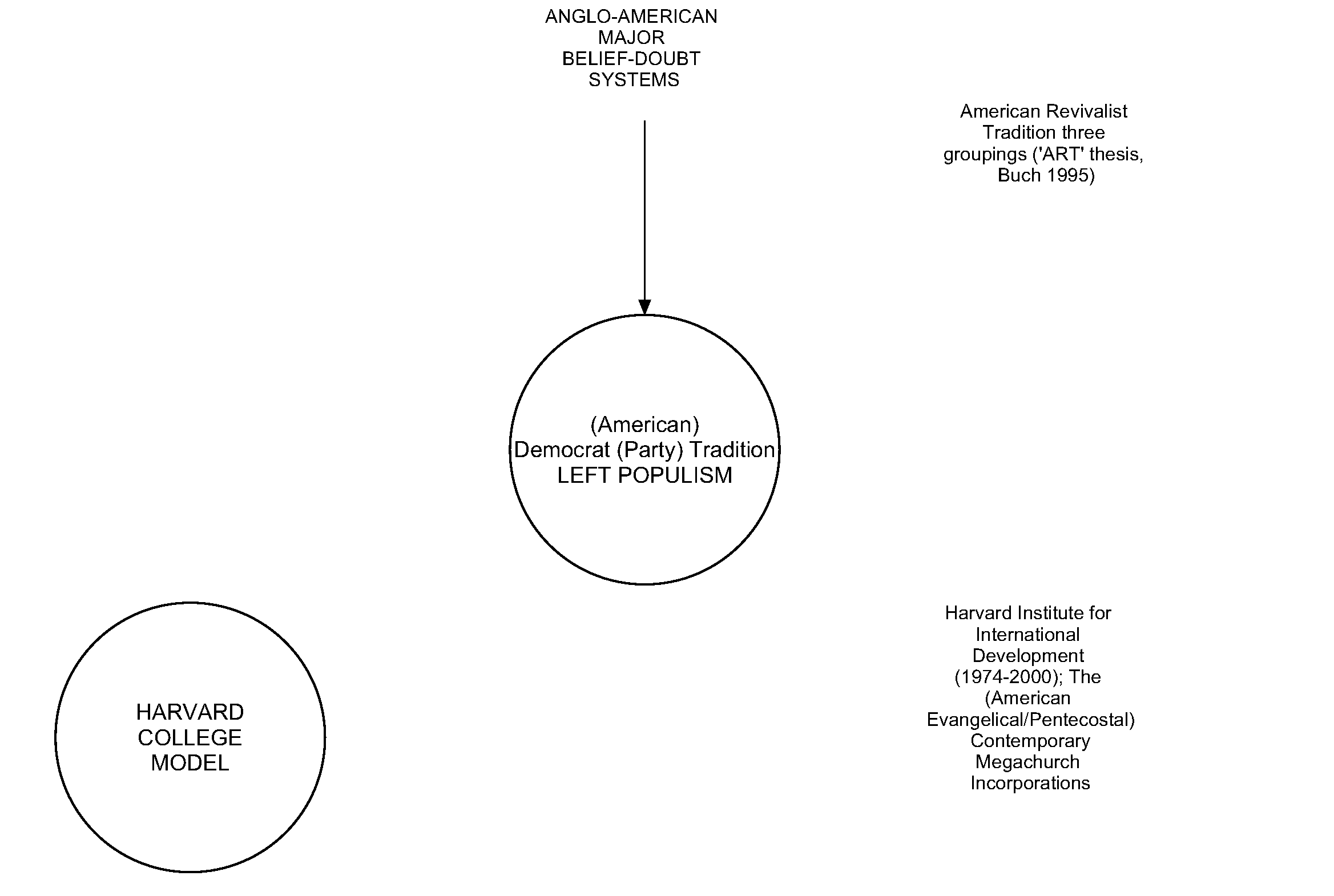

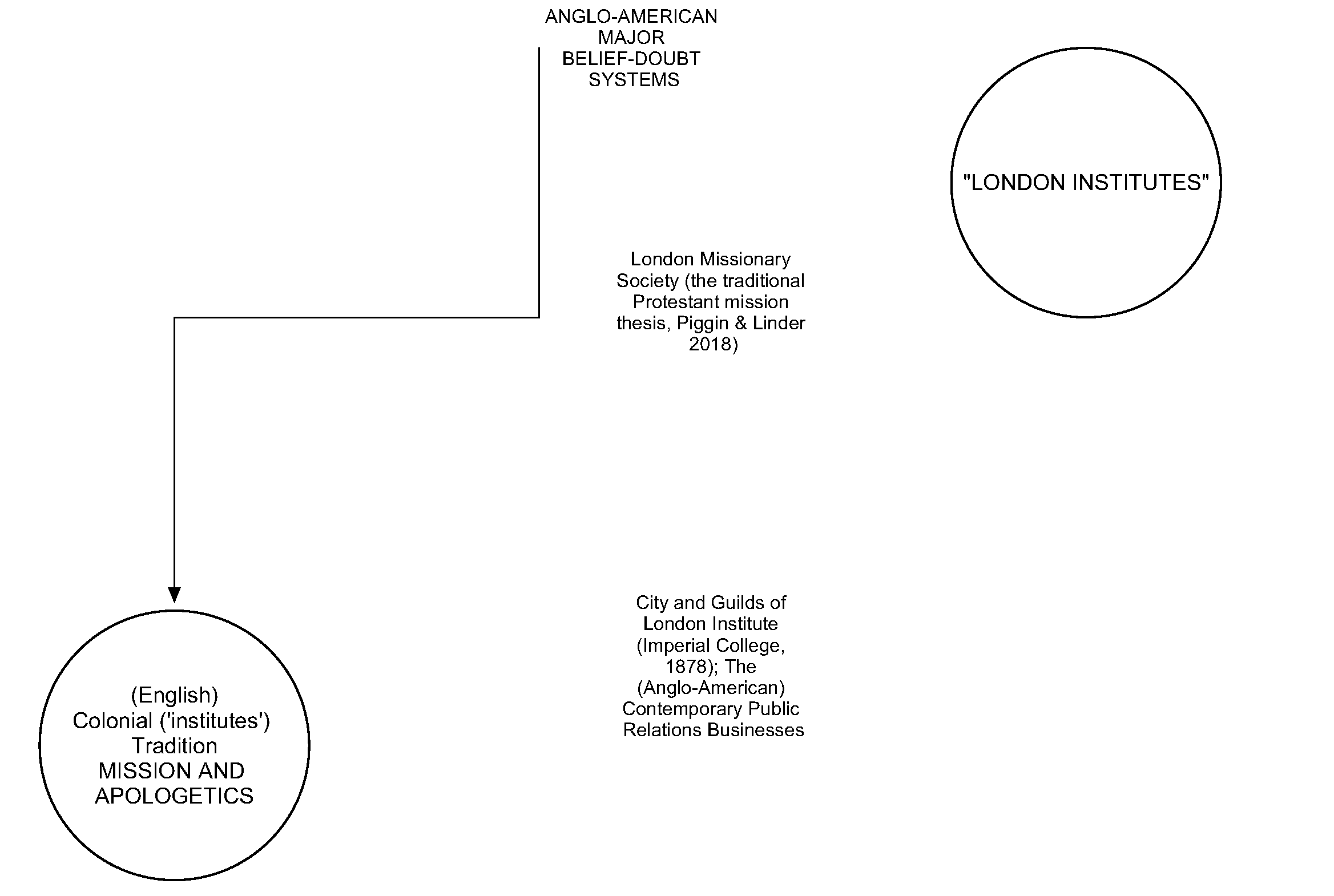

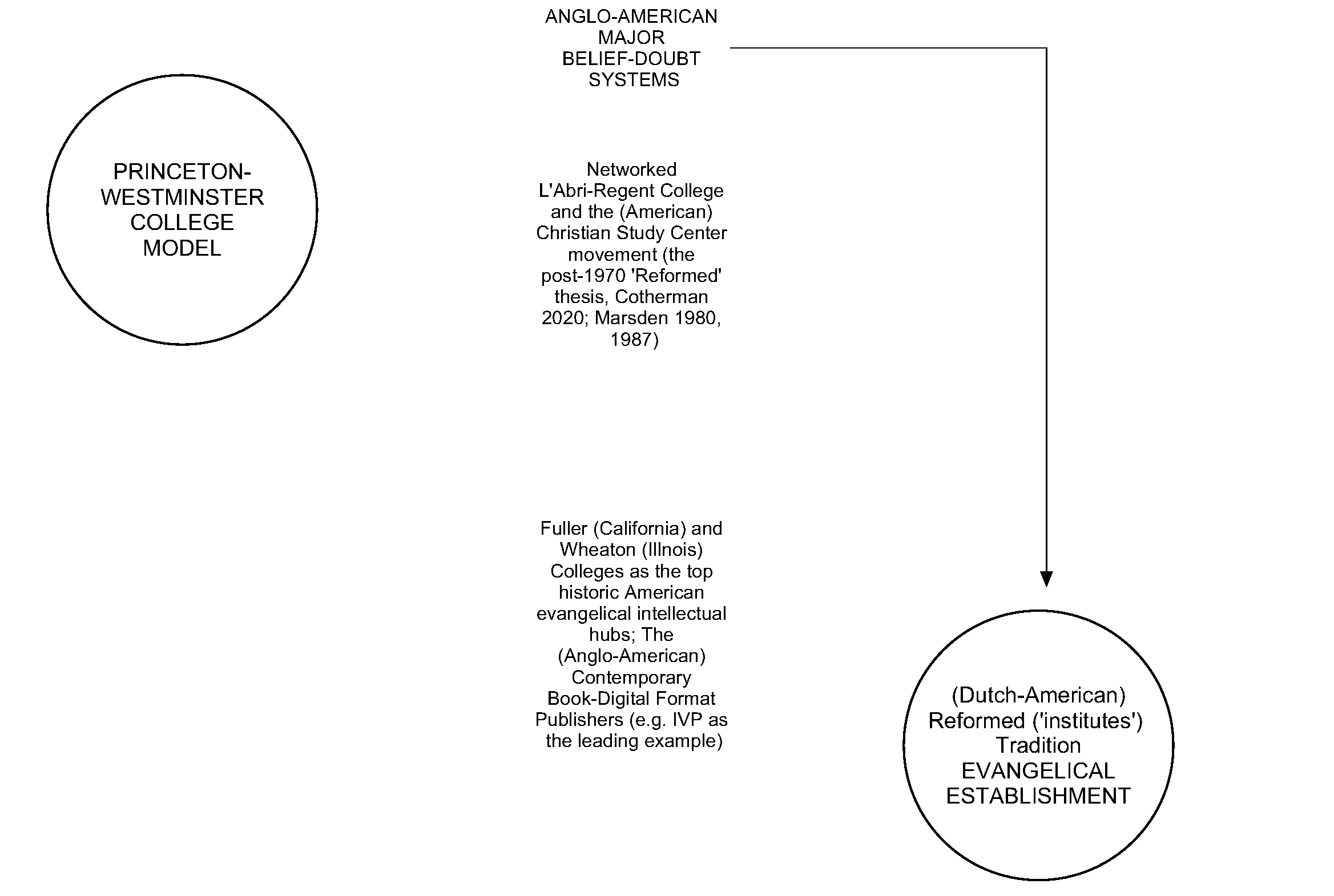

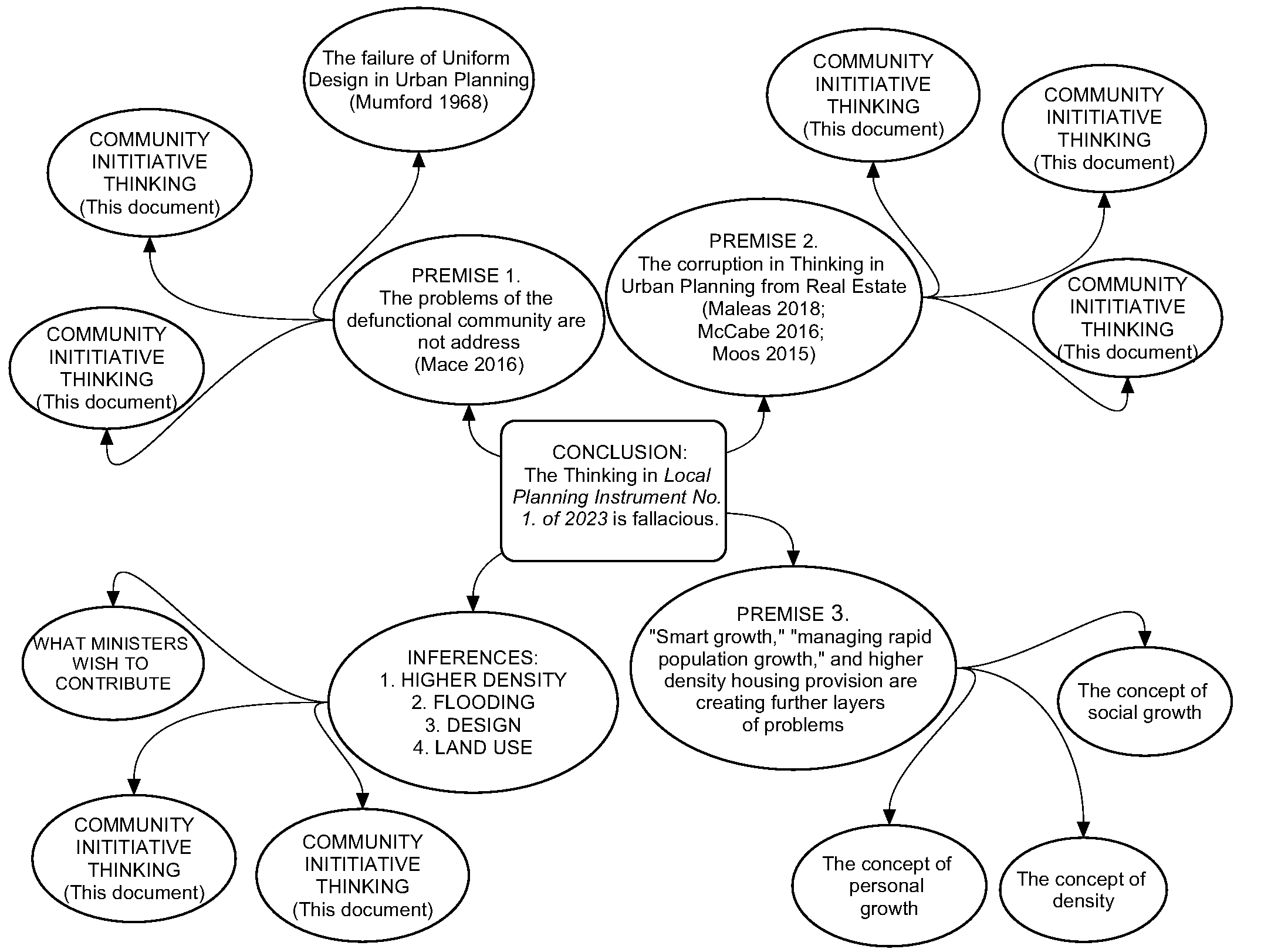

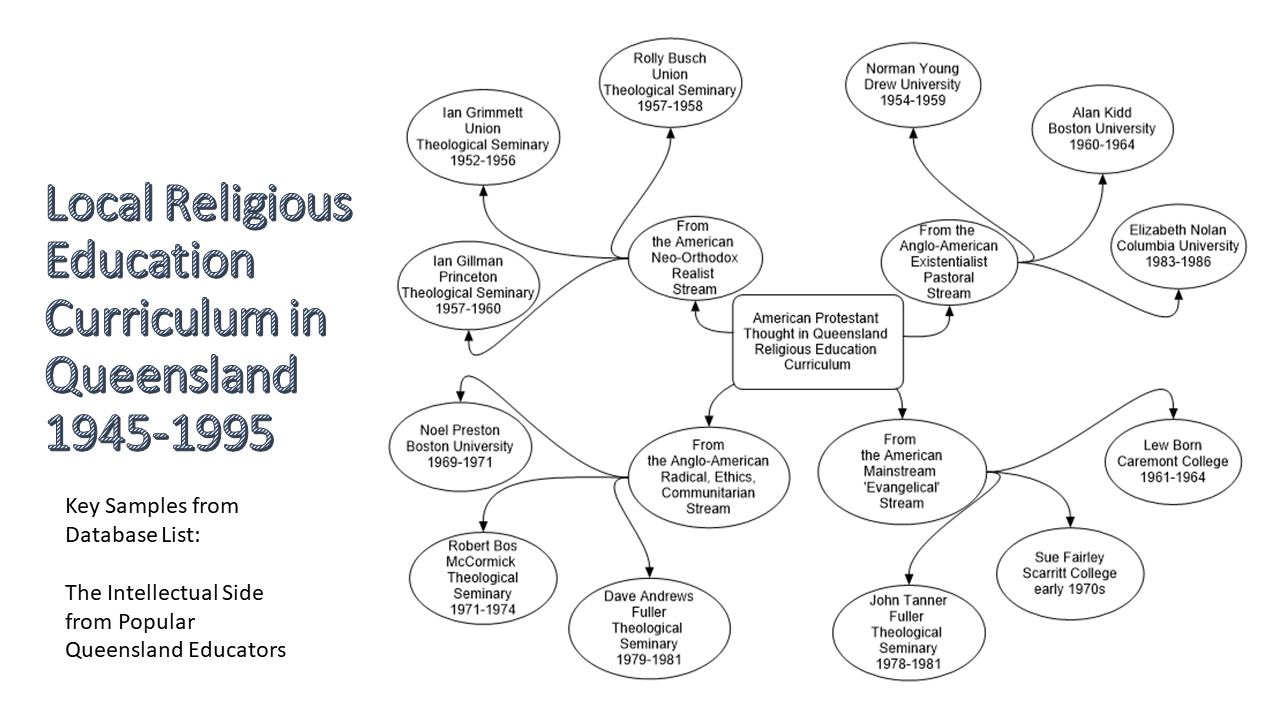

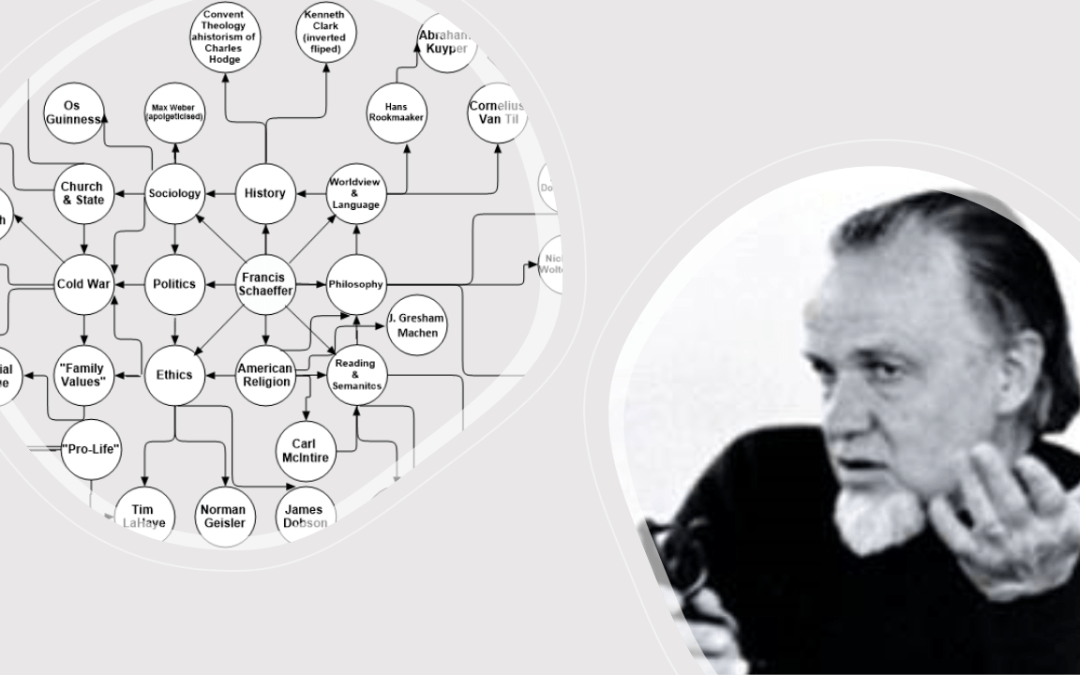

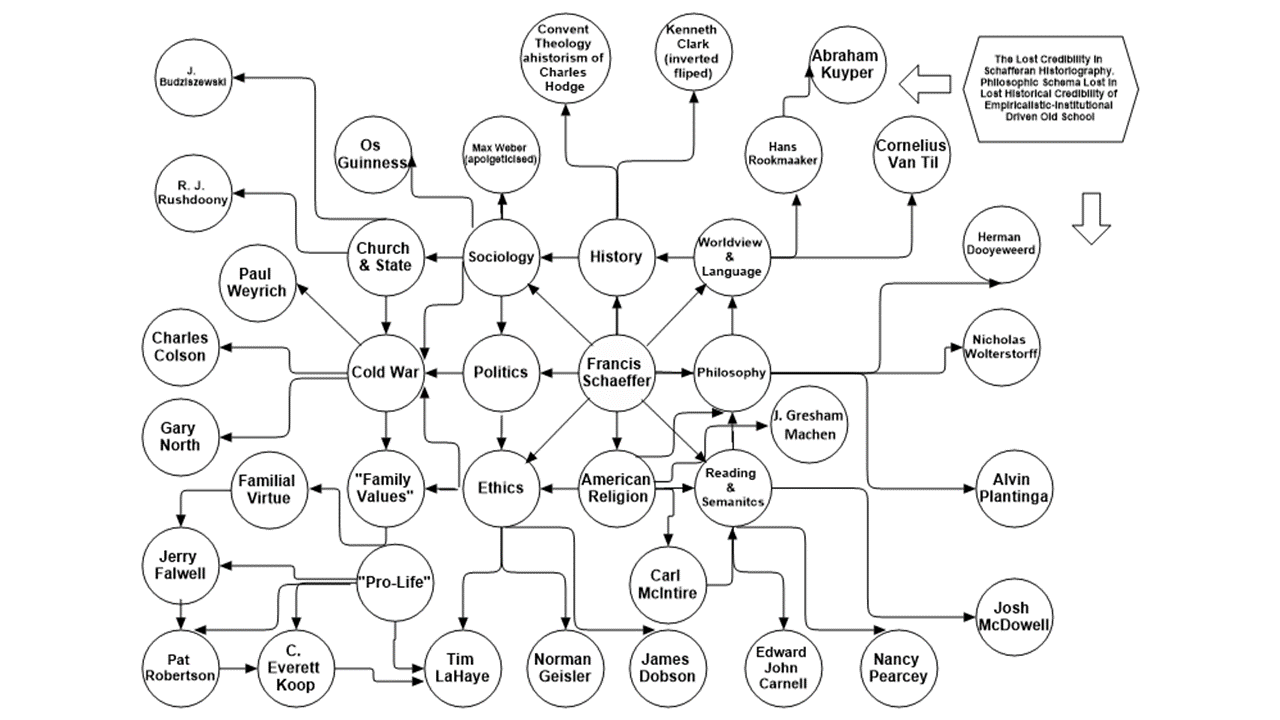

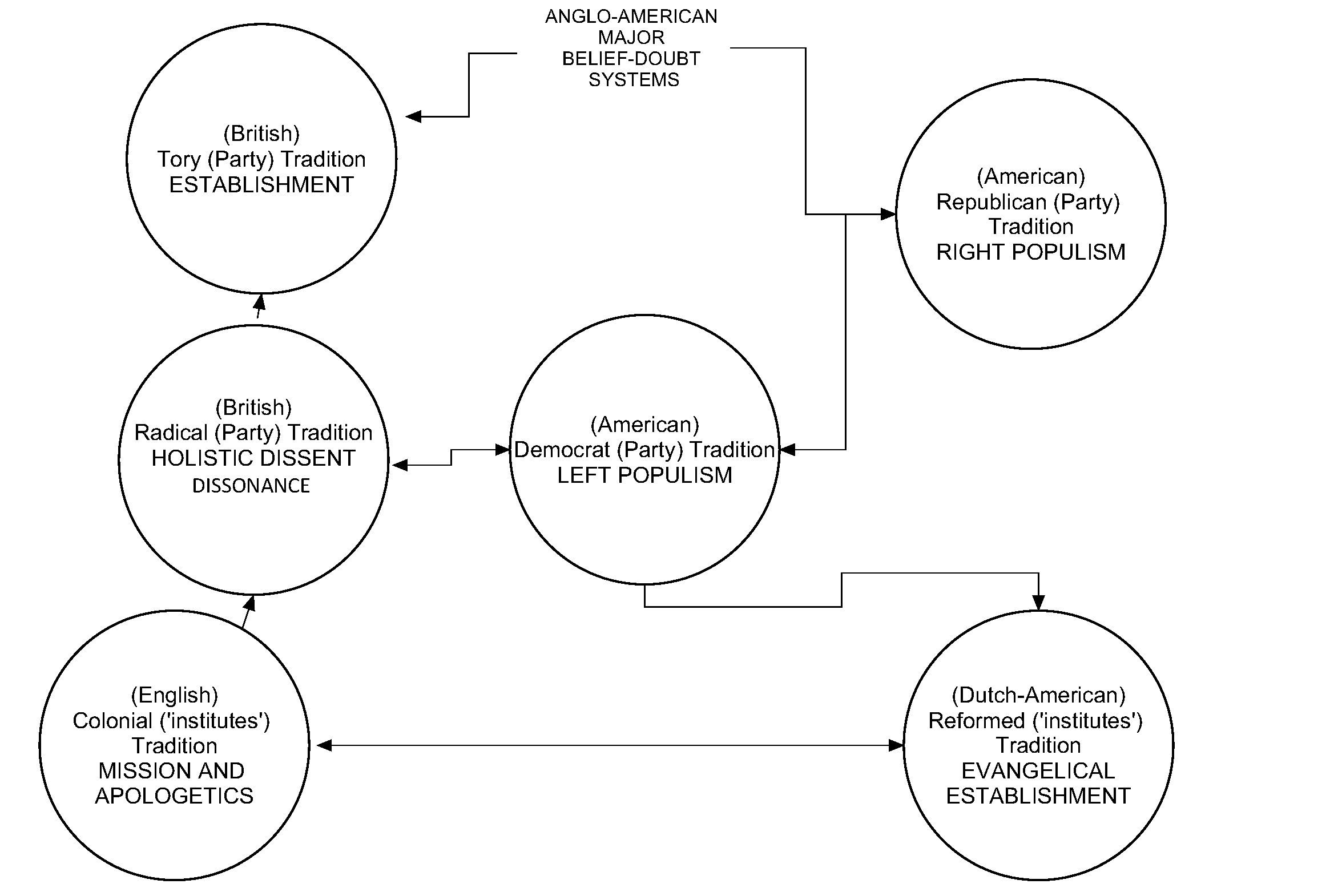

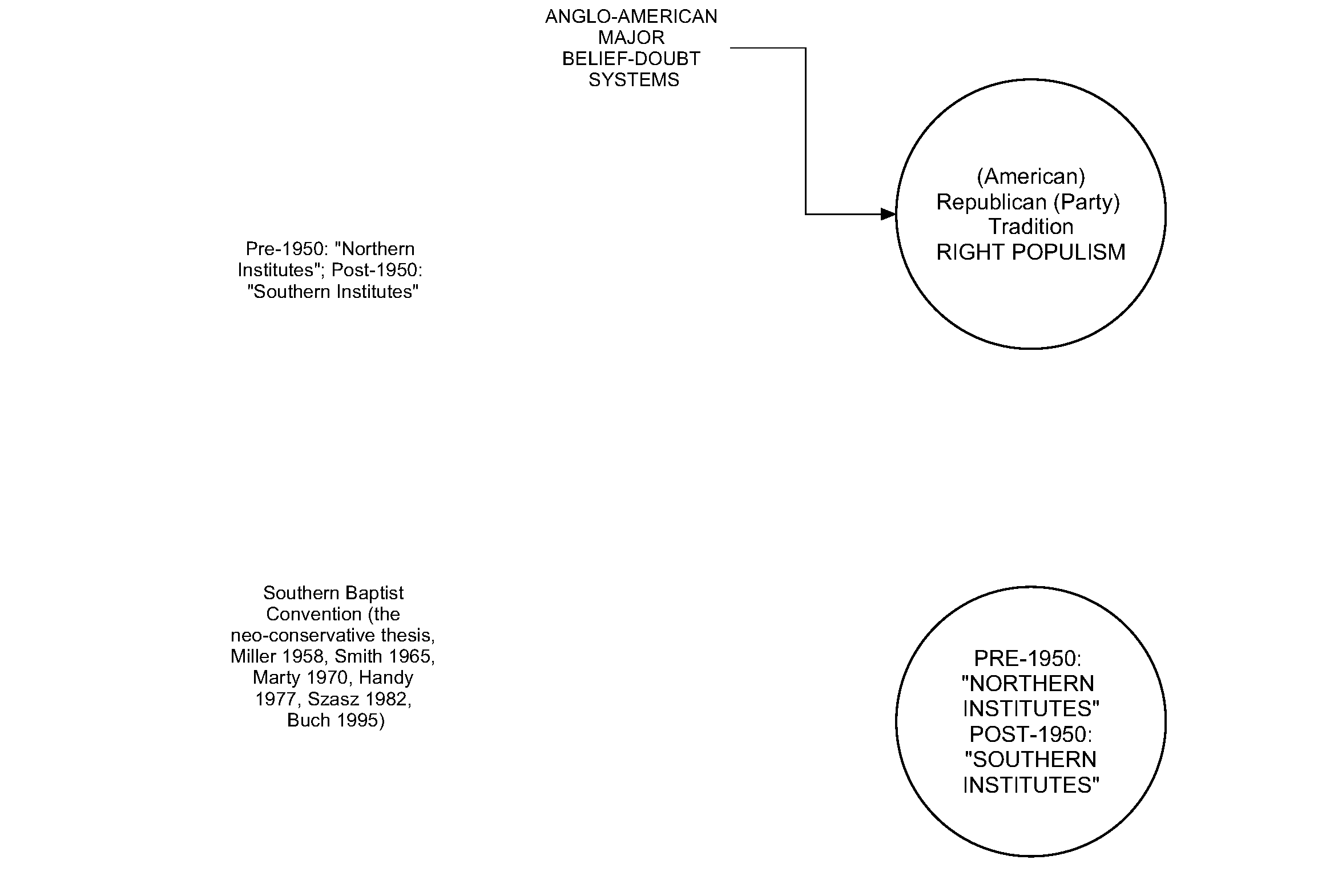

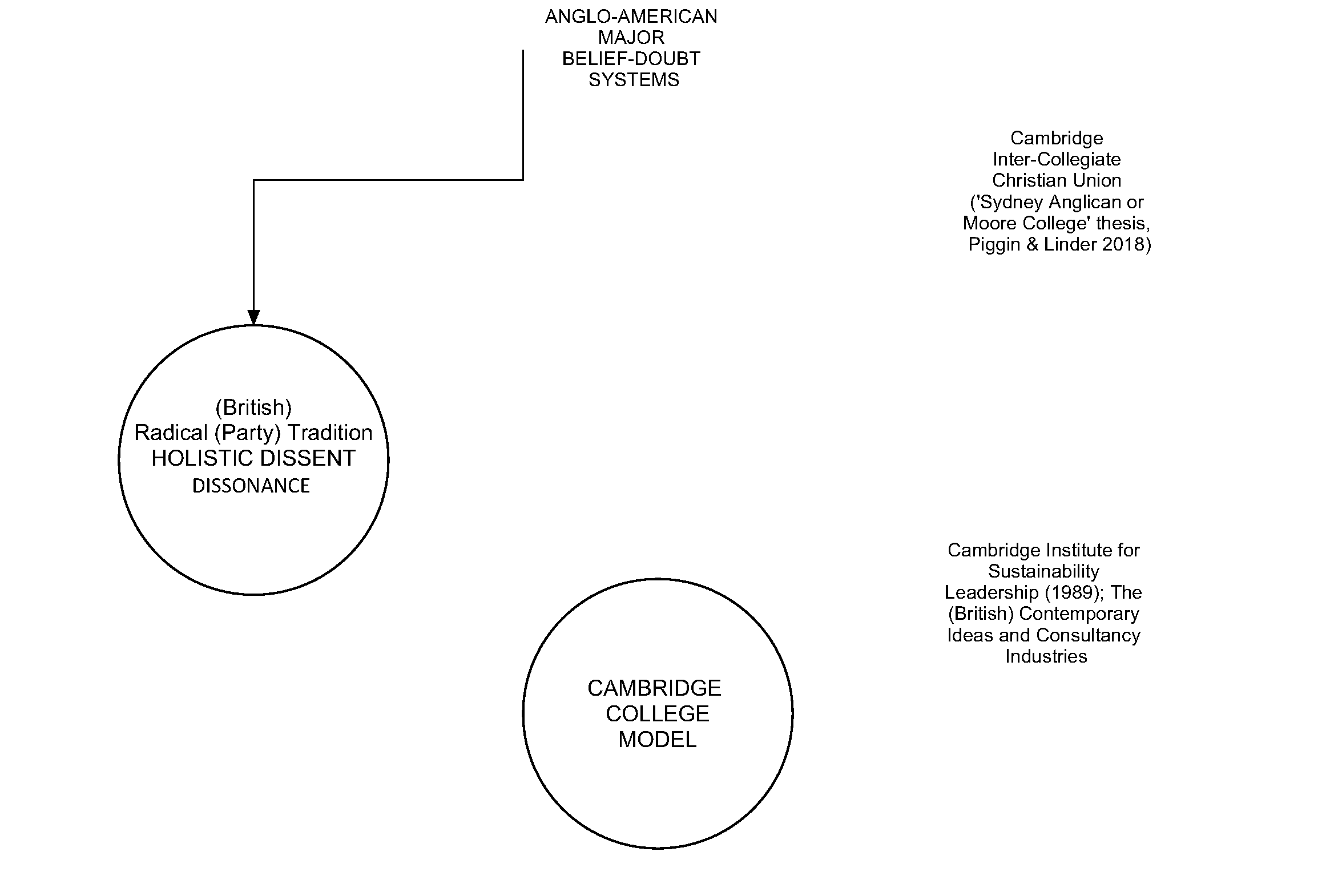

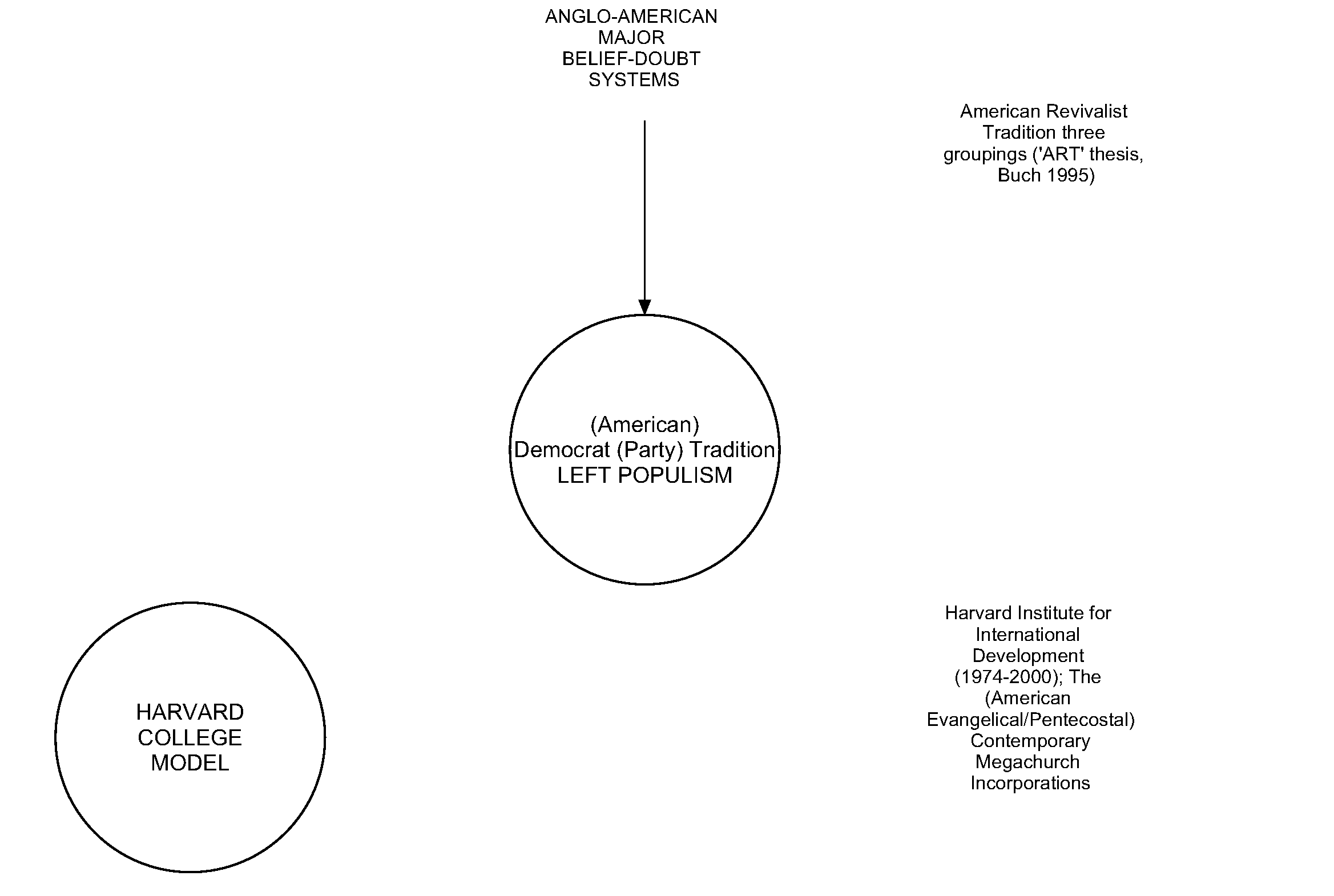

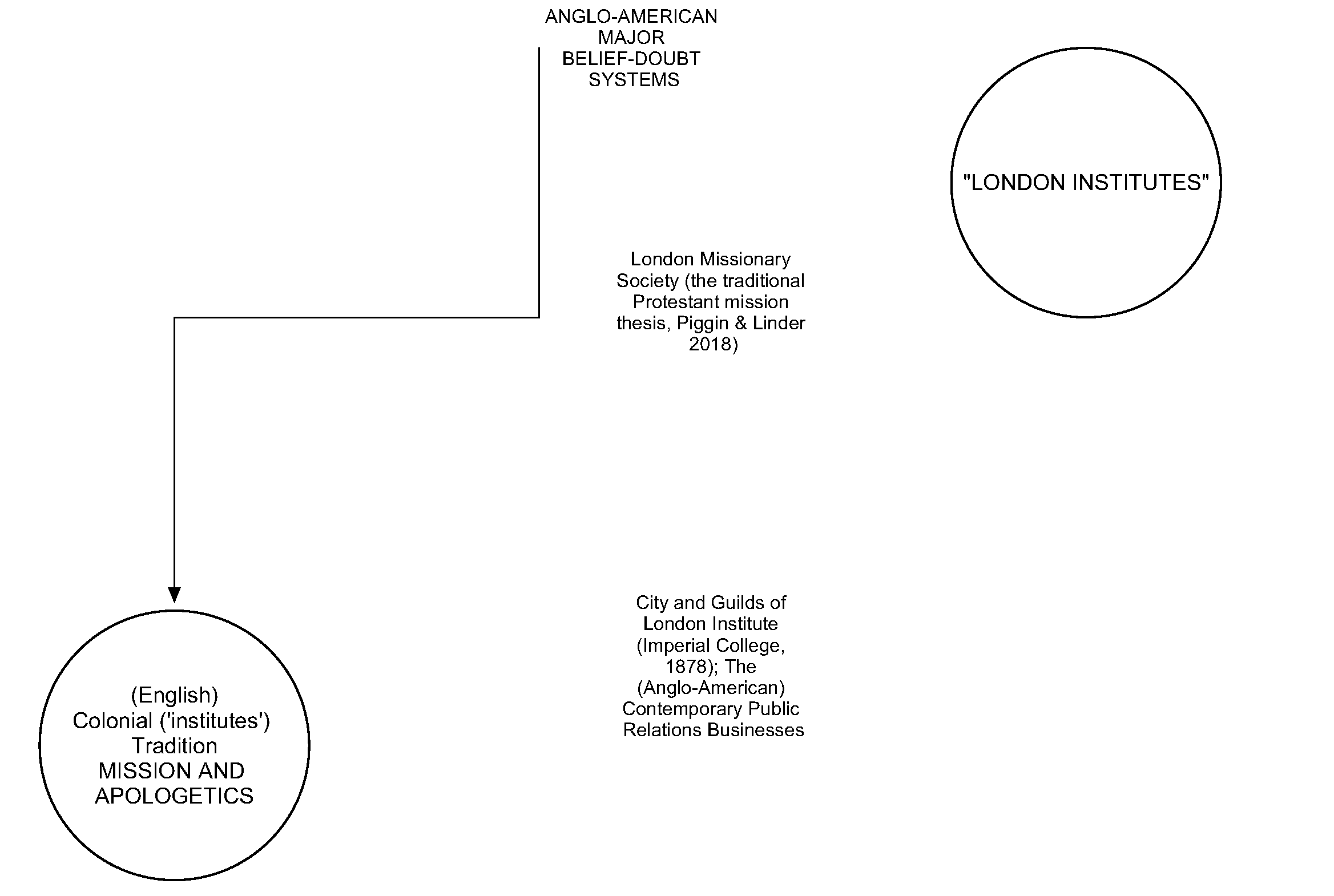

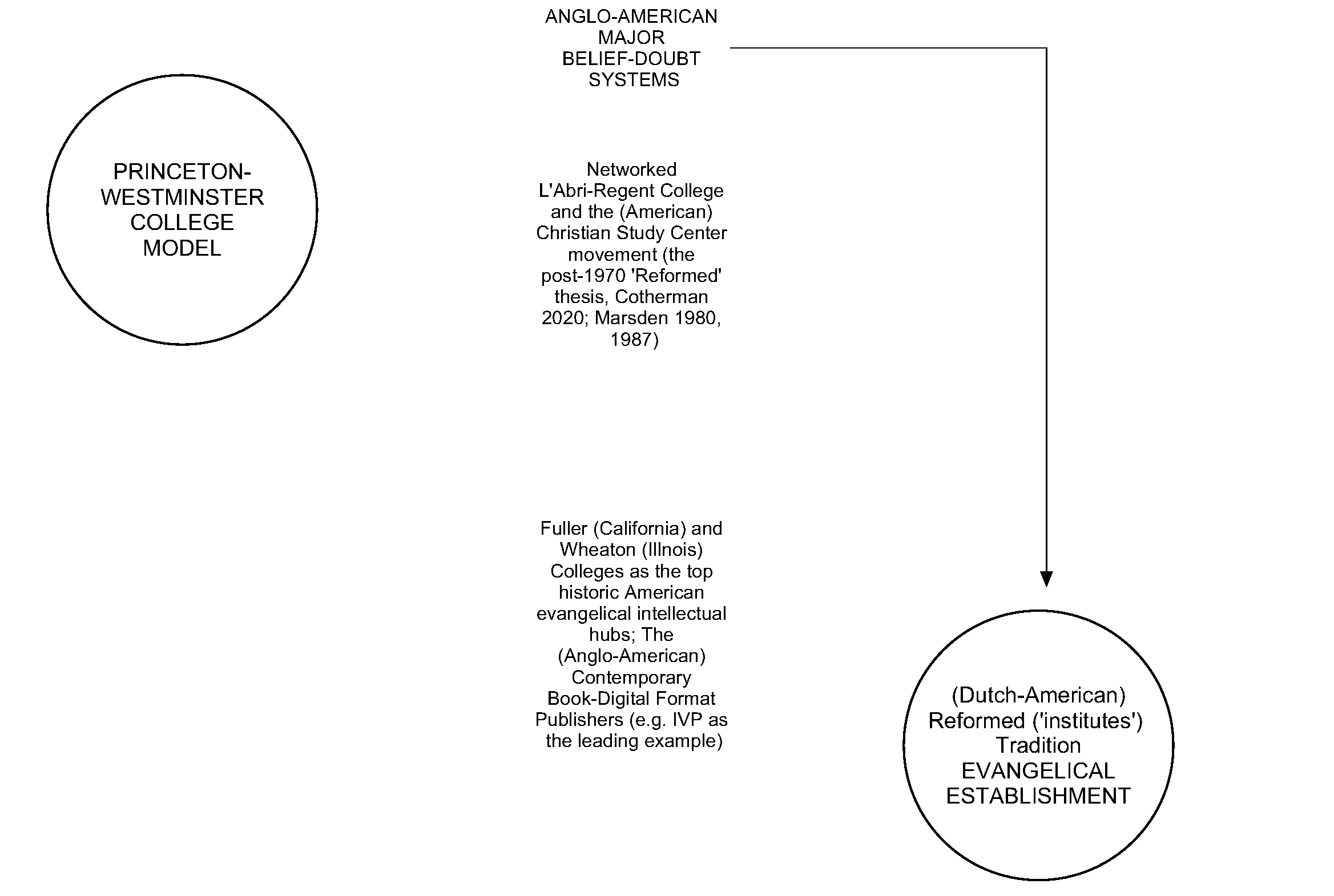

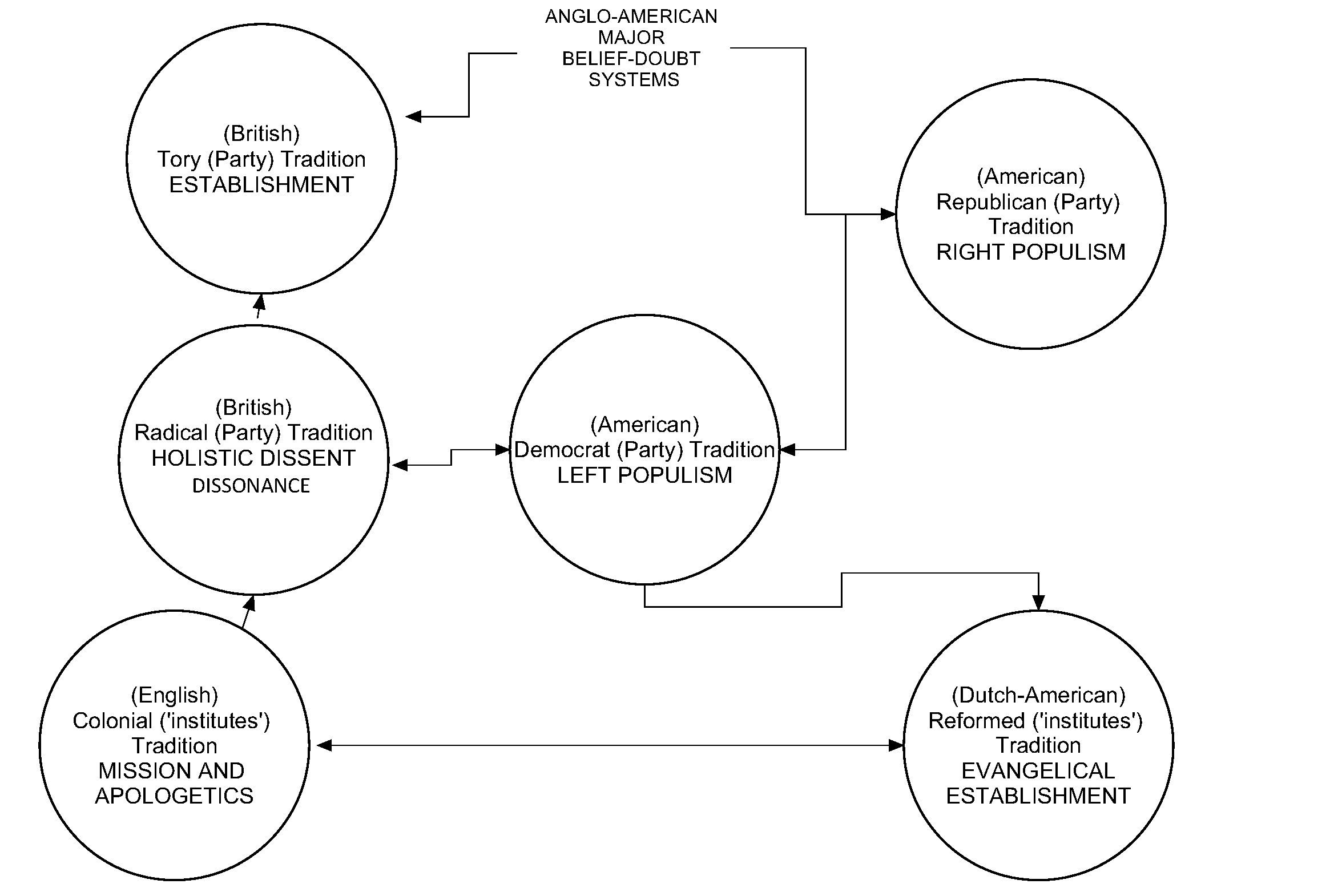

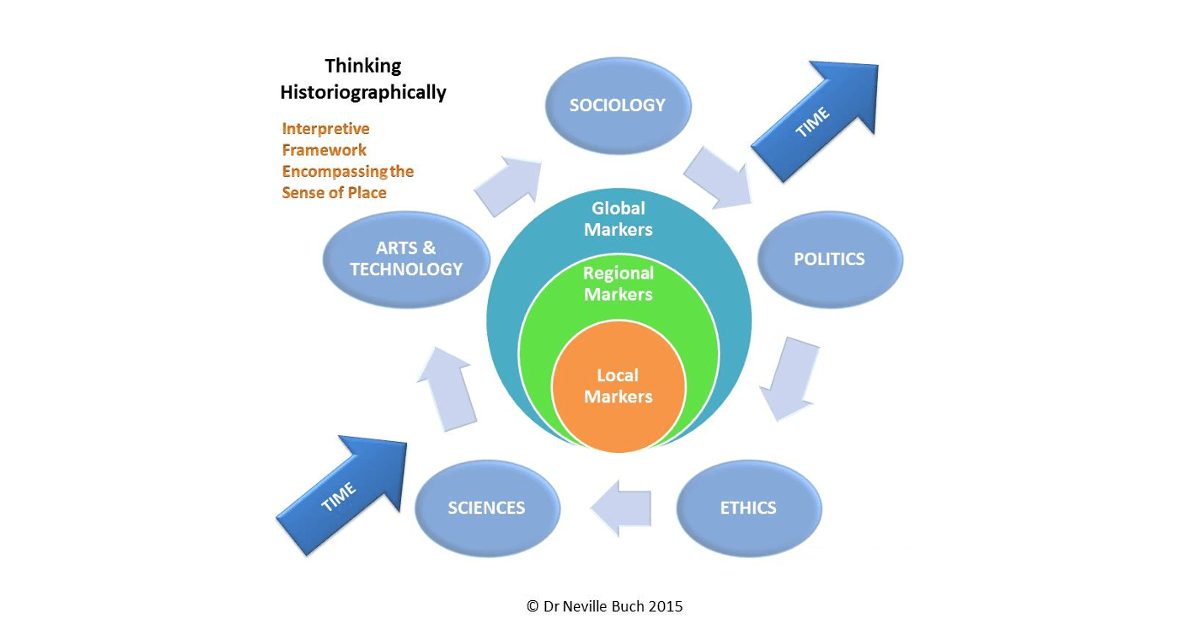

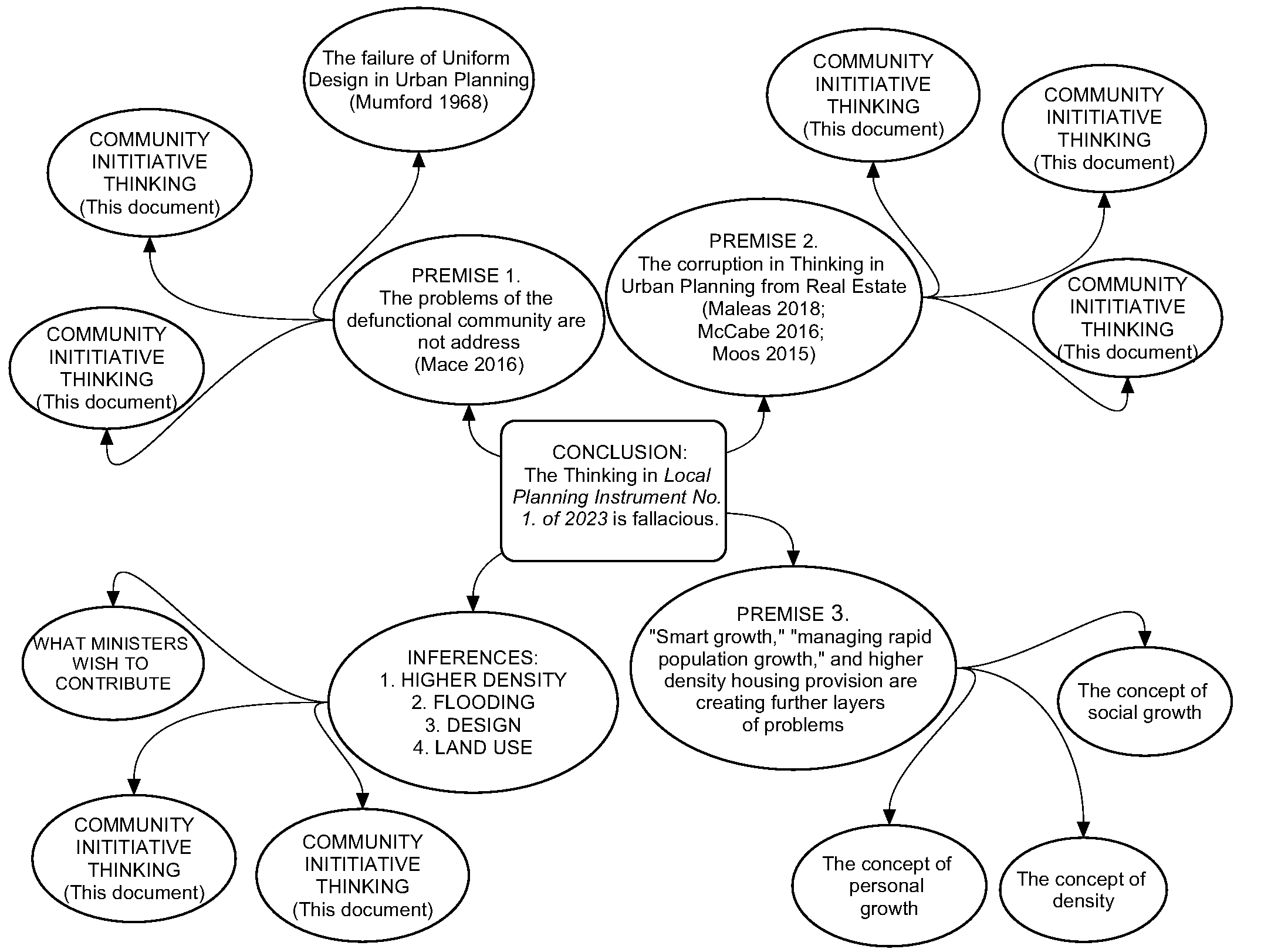

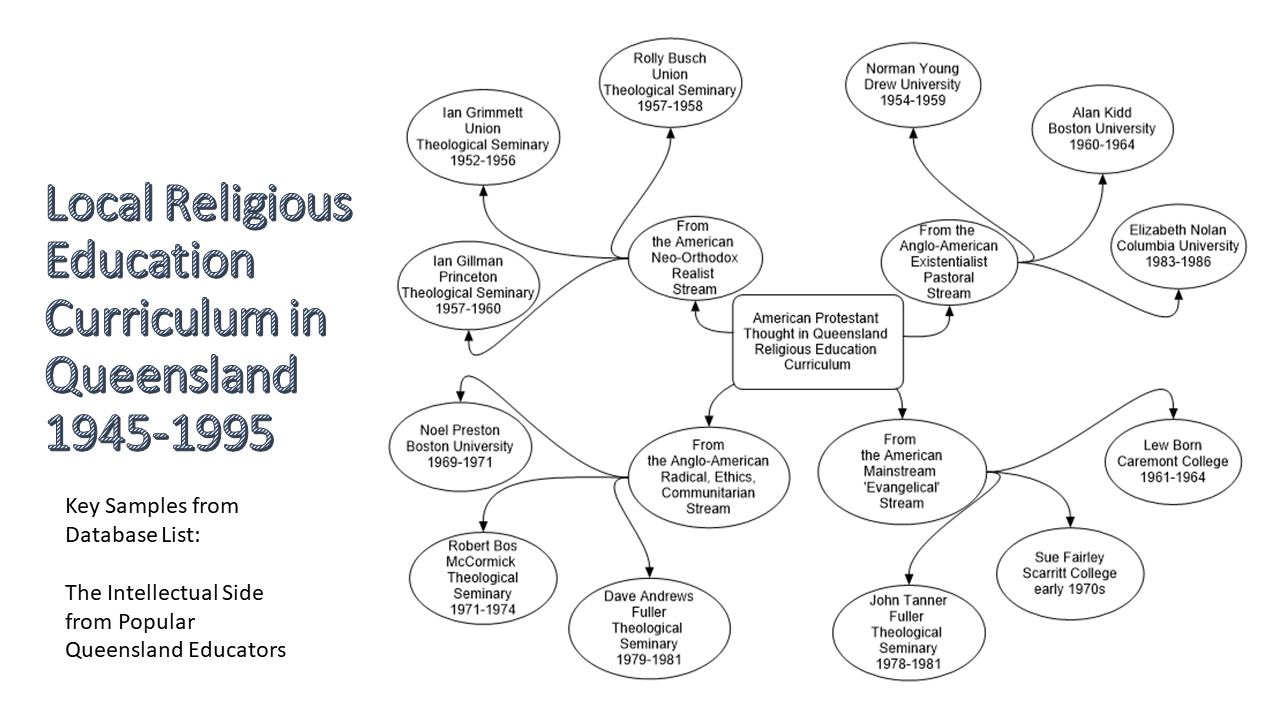

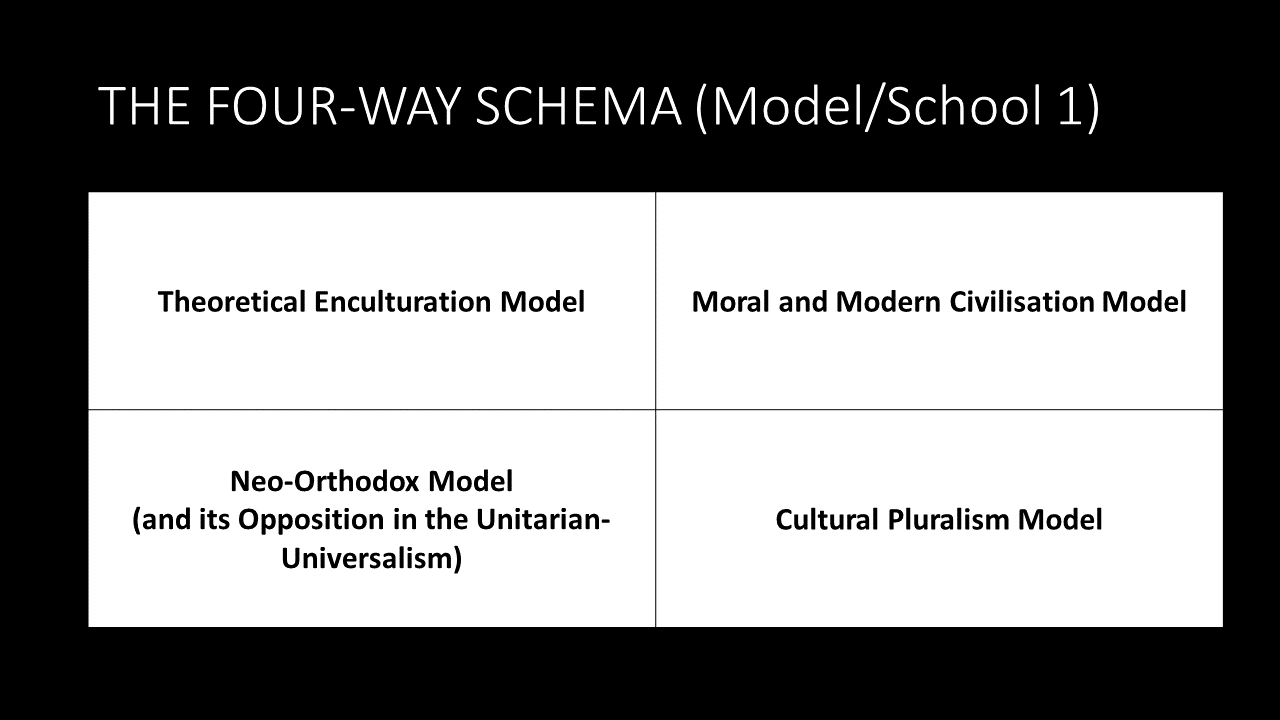

This blog article, as part of a series, demonstrated that much of Christian Apologetics is intellectual nonsense and focuses on the apologetics of Francis Schaeffer (1912-1984). If you do not know who Francis Schaeffer is, I suggest you click the link to the Wikipedia entry. This a central linkpin in the series of blog articles because, as the intellectual mapping graph on Francis Schaeffer demonstrates, Schaeffer linked most, if not all of the thematic failures in Christian Apologetics, as it is debates in the mainstream disciplines; even as this promotion (“PR”) of Christian Orthodoxy, declares all of its positioning across intellectual themes as “correct belief” in Lord Jesus Christ. The final conclusion is that the “Christian Apologetic” is nothing more than of a dominion theory, which is a majority thinking of American evangelical believers (i.e., right-wing and where the American left-wing evangelical positioning is the minority), BUT a small fundamentalist minority in the Christian world. To those who label themselves “Neo-Evangelical” and disagree with my own positioning in the argument, I would ask you consider the weight of evidence in this blog article, and be open to the suggestion that you may have not understood the story of the “Neo-Evangelical rebellion” from fundamentalist orthodoxy, as shown in the historiography of George Marsden and Mark Noll. The historiography starts the analysis as discipline learning, but it then proceeds into seven other sub-disciplinary areas.

The Evangelical Ultimate Concern: “Authority”

In 1987, George M. Marsden, in Reforming Fundamentalism: Fuller Seminary and the New Evangelicalism, pointed out several factors about the life and role of Francis Schaeffer to give members of the Neo-Evangelical movement concern.[1] In the 1940s Schaeffer was a keen defender for the Carl McIntire’s Bible Presbyterian movement. Marsden notes Schaeffer’s historical reading of American and global events was in terms of the fundamentalist theology of McIntire and J. Gresham Machen, and Schaeffer was influenced in this way from connections with the evangelist Wilbur Smith. Schaeffer was part of the National Association of Evangelicals fold because he could play somewhat, in the naive popular view, between the fundamentalist’s ‘Bible as inerrant’ and the neo-evangelical’s ‘Bible as infallible’, but for Schaeffer they were different concepts, and although he dressed his historiography in more moderate language of a “liberal” anti-modernist stance, his anti-modernism was fundamentalist through and through. One reviewer put it, “Schaeffer feared such a softening of fundamentalism allowed the victory of modernism.”[2] Today, the fundamentalist agenda of Schaefferan apologetics should not be doubted.[3] But the history is simply ignored in the evangelical argument over theological authority. It is so strange to the historiographer working in disciplinary knowledge, and not in apologetics. George Marsden’s Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth Century Evangelicalism 1870-1925 (1980) had explained so well what Neo-Fundamentalism of the late twentieth century had become, and it seem not understood in Christian college’s apologetics programs.

The ultimate concern here is of evangelicals is “Authority” where the semantics can be read in such different ways. Molly Worthen’s Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism (2014) tells the story.[4] Schaeffer was a fundamentalist believer. His historiography was known as the “line of despair.” Schaeffer had convinced Pat Robertson to abandon his early resistance to political involvement and assume a leading role in the Religious Right (called, ‘New Christian Right’; NCR). Schaeffer forged the 1980s NCR consensus. Schaeffer anticipated the apologetic design of the Christian schooling movement in the 1990s. Schaeffer was able to work-in his apologetics with the premillennial evangelicals, such as Hal Lindsay, even though, his political vision was postmillennial. Schaefferan apologetics is pseudo-intellectualism. Today, his ‘academic’ followers, such as Ronald Wells, water-down the intellectual problems in Schaeffer’s thinking. The authority which Worthen referred to is often less than concepts of biblical authority than of evangelical politics. Worthen is correct.

The chief fallacy is that Schaeffer represented a centrist position, and the idea came from Schaeffer explaining his own apologetics as a middle path between evidentialism and presuppositionalism. However, as the analysis of the eight wide sub-disciplines shows that Schaeffer was well out of his depth in the disciplines of modern scholarship. The complexity of the nuanced arguments as political theology should not deflect the central problem here. For example, Nord (2001) in raising issues from the educationalist discipline, and reviewing Fritz Detwiler’s Standing on the Premises of God: The Christian Right’s Fight to Redefine America’s Public Schools (1999) writes:[5]

“While Detwiler locates the Right historically in American fundamentalism, he places Dutch Calvinism at the heart of his narrative, and he argues that Francis Schaeffer (“the single most important figure in the development of the contemporary Christian Right”

) and Rousas John Rushdoony give the Right its identity (p. 24). (He makes only the slightest of passing references to Rushdoony’s desire to apply the death penalty to enough offenses to curdle the blood of most members of the Christian Right; see p. 251.) In fact, Detwiler may well place too much emphasis on Schaeffer and Rushdoony and, toward the end of his book, he acknowledges that Dutch Reformed theology cannot unify the Right – and this poses something of a problem for it (p. 239; also see p. 130).”

It is true that no single theological or ideological analysis defeats the apologetics of Francis Schaeffer, but together an intelligent evangelical believer must see the utter nonsense and wonder why the evangelical institutions keep the fallacies of Schaeffer going.

- Critiques with the Whole Sub-Discipline of Historiography

Evangelicals, and others, as historiographers, began with a very charitable view of Francis Schaeffer’s positioning. In this regard, it was too charitable to Schaeffer’s fundamentalism, and it has continued into the new century.[6] Mark Noll (1994) in the classic work, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, merely points out that Schaeffer had drew attention to “the theological meaning of general cultural developments”.[7] From recent reviews of the literature, Noll (2015) does not seem interested to be drawn into the argument about the nature of Schaeffer’s apologetics, but Noll neither entertains Schaeffer’s nonsense historiography; deferring to those American historians who are harshly critical of Schaeffer’s pretence to accurate historical analysis.[8]

Looking at the history of the Carter administration, Freedman (2005) stated that “Jerry Falwell and Francis Schaeffer argued a similar case from a conservative perspective” as the liberal theologian Reinhold Niebuhr had on Christians participating in politics. Falwell’s interest in Schaeffer, though, was very un-Niebuhrian, that the modern ‘monolithic consensus’ would mean “…art, music, drama, theology, and the mass media, values [would have] died.”[9] It was an anti-modernist polemic unfit in the thinking of the liberal Niebuhr brothers. Still, from recent works of the late decade of institutionalised evangelical believers, there has been trouble in capturing the significance of the Falwell-Schaeffer connection.[10]

In fairness it was Freedman’s passing remark, and he had cited others who offered a much more nuanced view:

“[Susan Friend] Harding [2000] argues that this process of secularization among fundamentalists made the religious right possible. In the 1970s and 1980s, Falwell and fundamentalist theologian Francis Schaeffer ‘pared essence’, down to its ecclesiastical essence, arguing that Christianity was best served through ministry in a broad sense. A logical conclusion was that Christians could use politics as a form of ministry.”

Grams (2007) also took this modest and charitable view too far, repeating the view of Schaeffer’s apologetics as it may have been in the 1970s counter culture.[11] Troubling is the way the views of Schaeffer, Arthur Glasser and David du Plessis, and Ronald Sider, are taken as the same whole in transformative mission dialogue. There is no capacity to discern very different semantics.

Scott Appleby (2002) is able to describe the fundamentalist imagination in the Schaefferan historiography.[12] “Their different settings, beliefs, and goals notwithstanding, Jewish, Christian, and Islamic fundamentalists interpret the history of the modern period, especially the twentieth century, in remarkably similar ways,” pointing out, “ ‘The bottom line,’ concluded the influential Christian thinker Francis A. Schaeffer, who have been speaking for the disgruntled Jews of Israel or the Muslims of Egypt, that at a certain point there is not only the right, but the duty, to disobey the state.” The imagination is of rebellion. Appleby goes on:

“The treachery of supposedly orthodox co-religionists is another fundamentalist history. Christian ideologues such as Schaeffer and Tim LaHaye point to the Christian foundations of the American republic and lament their erosion the hands of secularized Christians. Jewish extremists see the peace movement in Israel as expressive of the fragmentation of Orthodox Judaism and the confusion wrought by that crisis. And Muslim extremists, whose reading of history-and plans to alter its course-have captured our attention in dramatic fashion since September 1, 2001, have their own distinctive litany of traitors and of heroes.”

The sub-discipline of historiography today has a wide and deep analysis on the subject of historical imagination of which Christian apologists completely miss.

It was Butler (2004) who clarified the problem for evangelical historians who were willing to listen, and doing so makes the evangelical connection to Catholic neo-conservativism:[13]

“It would belabor the point to stress that theological ideas have helped propel the new Christian Right from the 1970s to the present. But the political scientist Michael Lienesch has described the importance of Francis A. Schaeffer’s 1976 book, How Should We Then Live? Schaeffer is not well known to historians, but his denunciation of ‘secular humanism’ heralded the vast literature that fueled conservative Christian activism after 1970 and shaped the style of cable television and radio talk that have expanded the movement since the mid-1980s. Patrick Allitt’s dissection of conservative Catholicism after World War II reminds us that religiously motivated political conservatism was not ubiquitously evangelical or Protestant. Participants in the intellectually pungent world surrounding William Buckley’s National Review always understood their movement as embodying a Catholic world view that could inform modern America. At the same time, National Review conservatives found it possible to support more secular conservatives such as Barry Goldwater, who favored the ‘the primacy of moral initiative” but from a more political than religious foundation.”

George Marsden is the best American historiographer for evangelical belief and American ideology. His The Twilight of the American Enlightenment: The 1950s Liberal Belief, provides a fair assessment in the decline of American liberalism from the perspective of Marsden’s traditional conservative beliefs:[14]

“[Marsden]… show[ed] how America moved quickly into a state of intellectual fragmentation. Mass culture became subject to impassioned debate while such authors as David Riesman, Erich Fromm, William H. Whyte, and Betty Friedan condemned a conformist mentality. Walter Lippmann called for a return to nature law, Reinhold Niebuhr advanced ‘Christian realism,’ and Daniel Bell and Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. expounded a non-dogmatic relativistic pragmatism that eschewed any quest for first principles. None, however, offered clear solutions to the country’s fragmentation. All this time mainline Protestantism was going into rapid decline, giving way to secularism and rightist fundamentalism. The author’s own sympathies lie most strongly with Martin Luther King’s call to honor a higher moral law, expressed in King’s 1963 ‘Letter from a Birmingham Jail.’ Drawing upon Dutch Calvinist theologian and prime minister Abraham Kuyper, Marsden, realizing that the consensus of the fifties is no longer possible, seeks a fully inclusive pluralism respectful of a variety of Christian and non-Christian worldviews.”

It is then clear that Marsden’s Reformed theological interpretation of Kuyper greatly differs to that of Schaeffer’s covenant theology. Marsden sets out the historiographical application of the Kuyperian theology, but showed no desire to condemn other worldviews from David Riesman, Erich Fromm, William H. Whyte, Betty Friedan, Reinhold Niebuhr, Daniel Bell and Arthur M. Schlesinger Jr. Indeed, aligning with King’s ‘Letter from a Birmingham Jail’ (1963) puts Marsden in conflict with Schaefferan apologetics, given most black theologians are in conflict with the NCR Schaefferan worldview. Swartz (2011) points to the divergent pathways in Left evangelicalism of the 1970s, referencing authentic black evangelical theology, “one that was biblical, grounded in ‘concrete sociopolitical realities,’ and that did not ‘merely blackenize the theologies of E. J. Carnell, Carl F. H. Henry, Francis Schaeffer, and other White Evangelical ‘saints.’”[15] Obery M., Hendricks Jr. in Christians Against Christianity: How Right-Wing Evangelicals are Destroying our Nation and our Faith (2021) clearly condemns white evangelical NCR theology, such that it is a wonder that white liberal evangelical can formally continue to fellowship with and acknowledge the advocates of Schaefferan apologetics.

Furthermore, the Kuyperian theology is difficult to translate if it is not historized, and that is a methodology Schaeffer rejected. Intellectual historians who specialise in the Dutch Reformed tradition debate these type of connections, and cannot be delivered in the art of apologetics.[16] Groothuis (2013) explained what Schaeffer got from the Kuyperian theological perspective:[17]

“For Kuyper, being a Calvinist meant far more than accepting the sovereignty of God with respect to predestination, although [Richard J.] Mouw [2011] addresses this important dimension of thought in the first chapter. God’s sovereignty was in addition God’s claim to the ultimate authority and normativity for all of life. As he famously stated, ‘There is not a thumb’s width over creation about which Christ does say, ‘Mine.’ Theologian, philosopher, and social critic Francis Schaeffer (1912-1984) made this theme central to his life and work.”

However, Groothuis denied the theocratic interpretation:

“But Kuyper was no theocrat, as Mouw emphasizes. He taught that Christ Lord over every sphere of life and that no sphere should overstep its domain. The church is not over the state; nor is the state over the church. Rather, are under the sovereignty of God and both should develop philosophies practices proper to their callings—all based on biblical revelation as well as truths known by common grace.”

That maybe well for Kuyper and Mouw, but it is very difficult to draw common grace in Schaeffer as he increasingly lashed out at ‘secular’ ideologies and those persons caught up in his blunt attacks. How well Schaeffer interpreted Kuyper via Herman Dooyeweerd (1894-1977), and Dooyeweerd’s follower, Hans Rookmaaker, is an open question here and beyond the scope of the research. However, Keene (2016) states that Schaeffer shared Dooyeweerd’s prejudice against synthesis and held only antithesis.[18] Keene says that the “espousal of antithesis needs to be set in the context of common grace just as with Kuyper.” Common grace, on the other hand, would seem would need to be synthetic to a measure; however, we stray beyond our purpose here.

Still the moderate evangelical apologist remains confused on Francis Schaeffer’s endpoint and claim him as among the critics of ‘Christian nationalism.’[19] Schaeffer’s critique of ‘Christian nationalism’ was directed towards a cultural Christian view of ‘Manifest Destiny’, but for Schaeffer it was only that the providence was not manifest in Americanism. Rather it was providential that the ‘Church of Lord Jesus Christ’ would reign, not merely as a promise, but an active fulfilment of the postmillennial hope.[20] Members of the Kingdom of God needed to seize what opportunity providentially prevailed, and the Church would trump the State. As Perlstein (2006) put it:[21]

“The evangelical theologian Francis Schaeffer preached the doctrine that Jesus would never come back until iniquity was conquered on earth. Newly politicized evangelicals joined in coalition with Catholics for whom intervention in worldly public affairs was second nature – and who now more and more identified themselves, in an increasingly liberalized culture, as conservatives. Both groups increasingly identified with a Republican Party more and more defining itself, with the aid of national leaders like Ronald Reagan and Jesse Helms, with what now became known as the ‘religious right.’ The pieces were in place for these social movement stirrings to begin to reconfigure the American political landscape. The organizational capacity of right wing social movements continued to grow.”

Perlstein here has articulate the postmillennial strategy. This is what Schaeffer’s ‘Christian Manifesto’ comes as the endpoint, in the exact same spirit of Karl Marx’s ‘Communist Manifesto’. Several conservative evangelical reviews of Worthen’s critique fail to get the point, as if orthodoxy authority is beyond serious and probing questions.[22]

Why is Schaeffer’s historiography difficult for many evangelical believers to discern? One answer is the poor biographies and hagiographies.[23] As Ingersoll (2009) asks:

“Was the ‘real’ Schaeffer the leader of the open-minded conversations at L’Abri, the Schaeffers’ retreat in Switzerland for young, searching evangelicals (a hippie, as his son, Frank, has described him), or the fundamentalist of the 1950s, or the religious Right leader of the 1980?”

The reference to Frank Schaeffer indicates the issue of the new generation reinterpreting the legacy of their parents. However, Barry Hankins’ Francis Schaeffer and the Shaping of Evangelical America (2008) has been able to generate a consistent mega-historiographical position; and with many reviews of the book, it has only reinforced an argument that Schaefferan apologetics overstep the evolution in knowledge from the disciplines into fallacious thinking and misinformation. Hankins’ main contention is “the tension between Schaeffer and his contemporary ‘Christian historians,’ George Marsden, Nathan Hatch, and Mark Noll.”

- Critiques with the Whole Sub-Discipline of Studies-in-Religion

Whether the failure of the apologetic approach is discussed in the congregations or college classroom, sometimes the religious institutions recognise the Worthen critique. Doenecke laid out the intellectual history in a concise summary:[24]

“Worthen offers an engaging road map through evangelical thought. Almost encyclopedic in nature, her book ably captures its richness and variety, and polarization as well. She begins her narrative with profiles of such intellectual evangelicals as J. Gresham Machen, Carl Henry, and Harold Ockenga, whose theology found fruit intellectually in Christianity Today and institutionally in the National Association of Evangelicals and Fuller Theological Seminary. Her narrative ends with the establishment of the Christian Right, as manifested in such figures as Jerry Falwell and Tim LeHaye [sic]. Certain sections of Worthen’s account are particularly fascinating, among them the debates over plenary inspiration of the Bible, relation to Roman Catholicism, and the Anabaptist renaissance spearheaded by John Howard Yoder and the Holiness one led by Mildred Bangs Wynkoop. Worthen presents the much-touted work of Francis Schaeffer as bordering on charlatanry and the ‘biblical ethics’ propounded by Reconstructionist Rousas Rushdoony as being downright bizarre. At the same time, she writes appreciatively of Jim Wallis, founder of Sojourners, and Notre Dame historian Mark Noll.”

The religion of American evangelicalism, outside the liberal framings of such believers, cemented in the 1970s with the Fuller reactionary neo-conservatives:[25]

“Events in the 1970s limited the reach of these non-Reformed reformers, however. Henry’s successor at Christianity Today, Harold Lindsell, published the polemical Battle for the Bible in 1976, charging anyone who did not affirm biblical inerrancy with apostasy. Reformed, inerrantist evangelicals used the context of the emerging ‘culture wars’ to clarify the boundaries of evangelicalism. Francis Schaeffer became the most visible of the ‘evangelical experts,’ as he expounded on ‘historic Christianity’ in lectures and books that reified the marks of true believers. Increasingly, those marks included commitment to the fights against abortion, liberalism, and secular humanism. This politicization of evangelicalism worried many non-Reformed evangelicals, especially Mennonites. But a greater number joined the fight against liberalism, convinced by Schaefer and other ‘idea men’ that they were charged with nothing less than the survival of historic Christianity, Western culture, and America itself.”

Those in the studies-in-religion discipline have no doubt that Schaefferan apologetics is skewed in cultural and orthodox bias.

- Critiques with the Whole Sub-Disciplines of Law and Political Studies: The Church-State and Civil Society Debates

The Schaefferan apologetics in the context of NCR operated on a narrow view and argument of the ‘public square’.[26] It is a legal perception on what ‘a Christian nation’ ought to expect. On the view of the Christian State, Ahdar (1998) points out, Francis A. Schaeffer, in A Christian Manifesto (1981: 121), rejected “The whole ‘Constantine mentality’ from the fourth century up to our day [and it was] was a mistake. … Making Christianity the official state religion opened the way for confusion till our own day”.[27] However, that semantics for centralists evangelicals of the 1980s and 1990s was confusing thinking, in that for Schaeffer it was a rejection of ‘secular’ statism. As it was articulated as one interpretation by Ahdar, as an argument against a Christian State, a militant theocracy:

“If establishment is good for society, is it nonetheless good for Christianity itself? Certainly, the strongest form of establishment, theocracy, is a form of government firmly rejected by several influential Christian thinkers. Church and state are viewed by some Christians as two separate realms not to be confounded.”

That is, though, one interpretation, and Ahdar’s remarks suggest another. Ahdar cites Schaeffer in the footnote but has confused the semantics of Schaeffer’s references which are, one hand, the old covenant of the Old Testament theocracy, and, on the other hand, the new covenant in a postmillennial promise of a literal theocracy. Given a fundamentalist reading, which has to be politically literal, with the two covenants in semantic agreement, the centrists are shocked by the discovery of the more forth-right Schaefferan theocratic statements in the context of the New Christian Right.

The Christian rightists had, in the 1980s and 1990s taken the moderate Christian apologists as fools. In the new century one still finds the naïve references to Schaeffer, Krabbendam (2011):[28]

“… Schaeffer was one of the rare fundamentalists who analyzed modern culture instead of rejecting it. The middle part of his life, from 1955 to 1970, was his most creative and rewarding period. He built a consistent worldview avoiding the division of reality in a realm of grace and of nature. This discovery broadened his cultural horizon and liberated him to explore contemporary culture. This made him address the immorality of race relations, economic injustice, and of abuse of creation, and opened his eyes for appreciation of art. These issues made him a unique progressive voice in the traditional Christian America.”

Many American progressivist evangelical believers would simply find these comments bizarre. It is quite clear that Schaefferan Apologetics is entangled in the schema of the New Christian Right.[29] At a forum in 2017 on ‘Studying Religion in the Age of Trump’ Schaeffer was labelled “the intellectual godfather of the Religious Right”.[30] Jerry Falwell and Francis Schaeffer were interlinked into a political program that, if centrists were able to look straightforward at the apologetics in wider disciplinary thinking, the apologetics would be seen as far too compromised for faithfully thinking of the neo-evangelical semantics.[31]

Furthermore, it is the entanglement of legal semantics which is the biggest problem that Schaefferan apologetics provides. Kersch (2016) demonstrates the confusion that a series of works brought to the understanding of the American legal system: John W. Whitehead’s The Second American Revolution (1982), R. J. Rushdoony’s Christian Reconstructionism (1973), and Francis Schaeffer’s A Christian Manifesto (1982).[32] Francis Schaeffer explained that:

“The government, the courts, the media, the law are all dominated to one degree or another by [the] elite. They have largely secularized our society by force, particularly using the courts. . . . If there is still an entity known as ‘the Christian church’ by the end of this century, operating with any semblance of liberty within our society here in the United States,” he writes, “it will probably have John Whitehead and his book to thank…”

The association with R. J. Rushdoony’s original The Institutes of Biblical Law (1973) would have also provided little doubt of Schaeffer’s rebellion theocratic turn. Quite simply, in this evangelical worldview there was only the current pagan laws of the American state and a call for instituting biblical law.

It could not be clearer that Schaefferan apologetics in relation to church-state analysis is opposed to disciplinary knowledge, but if it needs to be clearer look to what Worthen (2008) herself said:[33]

“The Christian reconstructionist movement – defined by theologians who explicitly assent to reconstructionism’s distinctives and are actively publishing and debating – is largely dead. Riven by internal schism, a distaste for politics or compromise, and an utter disdain for anyone who dared disagree, the movement imploded in the mid-1990s. In Ventrella’s view, this was the best thing that could have happened for Christian reconstructionism – for now that no one is worried about keeping to the party line or claiming credit, its ideas are at liberty to filter into America’s cultural bloodstream. ‘The ideas get diffused, and the better ones get traction,’ he said. ‘It’s like Francis Schaeffer said: worldviews are more often caught than taught. And you see the evidence of Rushdoony’s influence everywhere, from the homeschooling movement to proponents of Intelligent Design.”

So, from Worthen, we get the view that reconstructionism of Schaefferan apologetics is intellectually dead from the 1990s, and yet it continues as college and homeschooling programs.

One other civil religion issue should be ought to be noted. Schaeffer was never known as a racist. In recent times there has been a body of literature which has challenged, not racism of the evangelical world, but the appeasing reading in evangelical historiography which whitewashed racism; Jesse Curtis’s The Myth of Colorblind Christians : Evangelicals and White Supremacy in the Civil Rights Era (2021) is a formative example. Although Kristin Kobes Du Mez in Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation (2020) has nothing to say on Schaeffer himself, De Mez does index Schaeffer with the NCR which De Mez see as the educational expression of white evangelical thinking.[34] This is why institutionalised evangelical believers miss the point: an inability to read the different semantics in the unfair charge of racism and the fair critique of white evangelical appeasement.

- Critiques with the Whole Sub-Discipline of Political Studies: The Cold War Debates

Schaeffer for nearly half a century after his death in 1984 set the pace of evangelical politics on the American domestic landscape.[35] “Late in his life, Schaeffer’s cultural engagement morphed into the apocalyptic culture-war politics”, stated Hamil-Luker and Smith (1998). From the early days, Schaeffer worked from his belief of “the mutual dependence of Christian virtue and political liberty.”[36] It created something very intellectually foul in the evangelical world. The historical details linking Schaefferan apologetics, dominionistic theology and politics and all the leading NCR organisation players together could not be clearer, and references need to be made than Weinberg (2021) is a good start.[37] The principle became the pathway in the transformation and electoral power of the American Republican Party since Ronald Reagan.[38] The connections are quite apparent to Noll (2015).[39] Ethicists studying closely religious ethics see the problematic nature of the connections.[40] As Northcott (2012) stated:

“Under the influence of Jerry Falwell, Francis Schaeffer, and the Christian Right more broadly, appeals to faith in public policy have become mainstream for conservative Protestants and Catholics. They produced the ambiguous fruit of the ‘faith-based’ projects of George W. Bush as governor of Texas, and then as President (Northcott 2004). But the positions Christian conservatives have promoted in their political interventions—against abortion, homosexuality, and taxes, and for capital punishment, foreign military interventions, and Israeli expansion—are so contrary to those of Christian progressives that the progressives have turned on the conservatives and suggested that ‘religion and politics do not mix’ (Hauerwas 2001b, 463). This dissension underlines the problem that afflicts both conservatives and progressives in their attempts to interpret or influence American politics: both lack a shared Christian moral compass because they are shaped more by the American way of life, and the ‘tyranny’ of individual autonomy writ large in the totalizing institutions of capitalism and the strong state, than by their shared identity as those called to follow the crucified Christ.”

Northcott’s remark ought to provide an evangelical believer the most devastating critique of Schaefferan apologetics.

Pierard (1995), even before the new century, had taken the analysis much further in the concept of civil religion.[41] “The religious right’s civil religion offensive was particularly apparent in two areas,” stated Pierard, “the assault on separation of church and state and the rewriting of history to prove that the United States is a Christian nation.” The issue of Christian nationalism raises the question how the “Cold War politics” might have gone beyond the domestic concerns to the Cold War politics of Americanism proper.[42] Here it seems that Schaefferan apologetics was once rooted in the Cold War of the 1950s before turning to the moralistic domestic concerns in the 1970s. Ruotsila (2013) identifies Schaeffer as part of the 1950s fundamentalist critics who attack Christian mainline’s thinking, and “regarded neo-orthodoxy as but ‘the new modernism’.”[43] Ruotsila cited the forgotten work of Schaeffer’s The New Modernism (1950). In this regard, it demonstrates the historical forgottenness of the Evangelical world when it is politically convenient.

- Critiques with the Whole Sub-Discipline of Political Studies: The Abortion and Family Values Debates

The politics in the American debate on abortion and what is described as “family values” is extremely entangled in fallacies and misinformation. The discipline of political studies and general philosophy does it best. Most of the literature cannot, though, be any more than descriptions, such as when Anthony Fauci (2014) provided an obituary for C. Everett Koop and made the connection to Francis Schaeffer.[44] The most informative side of these debates are not in the literature of political studies but in the literature of epistemology and ethics.

During the 1970s and early 1980s, Schaeffer was highly-visible in a public globalising stand against abortion, infanticide, and euthanasia. For those who had different sets of ethic thought, such as Hamil-Luker (1998), Schaefferan apologetics had set a barrier: “fundamentalists have historically erected subcultural barriers behind which to preserve the purity of their faith.”[45] The outcome is an entanglement casted as an internalist projection on the interior of the worldview. As Weinberg (2021) well-described the projected outlook of the NCR:[46]

“[Pat] Robertson hailed the wisdom of the nation’s founders who created a country ‘under God.’ He bemoaned the state of America, which in the previous quarter-century had strayed from ‘our historic Judeo-Christian faith.’ Public schools had replaced moral absolutes with ‘values clarification’ and ‘situation ethics.’ They had replaced the ‘Holy Bible’ with the familiar pantheon of communist and evolutionary evil: Charles Darwin, Karl Marx, Sigmund Freud, and John Dewey. Young people were learning that ‘if it feels good, do it.’ For conservative Christians paying attention to the warnings of Francis Schaeffer, Tim LaHaye, and the like, the ‘whirlwind’ of immoral consequences was also familiar: one million teenage pregnancies and four hundred thousand abortions each year; a massive number of sexual assaults; and an epidemic of sexually transmitted diseases, including AIDS.”

The ‘fundamentalist’ error is the presumption that their ideological analysis in any way fits as well-connected worldview in relation to disciplinary knowledge. The irony is that the Schaefferan apologists today seek to flip the argument as an ideological critique which they misbelieve is nuanced. In the review criticism of Elizabeth Mensch’s and Alan Freeman’s The Politics of Virtue: Is Abortion Debatable? Steffen (1995) had pointed out:[47]

“While I am relating the Mensch and Freeman analysis in broad strokes, the detail of their picture of what lies behind the move toward absolutist discourse is intriguingly made. Good historical detail is provided on, for instance, various divinity schools (e.g., Princeton) and on the Randall Terry and Jerry Falwell influence of Francis Schaeffer. What becomes more problematic in their analysis is the way in which the authors adopt a point of view towards the secular, for in their effort to dissociate themselves from the rhetoric of the conservative critique of secularism (i.e., ‘secular humanism’), the authors still manage to attach to ‘secular’ a negative charge that conservatives will find laudable (Furthermore, I would never gloss over the ‘death of God’ movement as cavalierly as they do, especially and feminist theology.)”

- Critiques with the Whole Sub-Disciplines of Philosophy and Literature: Hermeneutics

It was not until Burton (1996) that modest educated evangelicals began to understand that the hermeneutics of the traditional approach of C.S. Lewis and of the neo-con radical Francis Schaeffer was poles apart to be different belief systems.[48] Schaeffer’s approach was mostly non-philosophical bound to scripture, committed to fundamentalist concept of inerrancy, using largely the hermeneutic framework of Cornelius Van Til, in ‘old-time’ (mostly nineteenth century Hodgean thinking) historiographical methodology, restricted to the correspondence theory of truth, and anti-Hegelian into philosophically ridiculous polemics. In one frame is hermeneutics about opposing all historical idealism, disregarding of any philosophic validate reasoning for different versions of historical idealism, and for that matter, an equal disregard for forms of historical realism. Contrast to the old form of apologetics from C.S. Lewis, Lewis thought that the American preoccupation with verbal inspiration was a theological red herring.[49] Lewis could work between historical idealism and realism but that is because most of his pop paperbacks were not apologetic in the semantic sense of American evangelicalism. Lewis was not concerned to defend exclusivist faith but only to defend an idea of basic Christianity in the context of the ecumenical mid-century.

The problem of apologetic hermeneutics, though, goes much deeper philosophically, to refusing to honestly engage in the “secular” schemas which are rejected with a mere preposition or cherry-picked evidential reference. As Davies (1997) stated on covenantal hermeneutics:[50]

“Lundin [Roger Lundin’s Culture of Interpretation: Christian Faith and the Postmodern, 1993] writes in what must surely be a tone of shocked incredulity (‘Can you believe it?’), for he makes no effort to answer or refute these poststructuralist claims. Instead, he writes as though it were sufficient merely to identify the scandalous scope of deconstruction – tracing the Enlightenment’s roots to the origins of Western thought – in order to summarily to reject it. Lundin assumes that the absurdity of the absurdity of such an audacious project should be self-evident to his readers. Such a project, however, will seem neither novel nor absurd for anyone who has worked through Herman Dooyeweerďs formidable A New Critique of Theoretical Thought, or Lev Shestov’s Athens and Jerusalem , or even Francis Schaeffer ‘s numerous books, for he or she would already have encountered it from within Christian thought itself. Why should we not want to subvert ‘conceptions of truth and transcendence that have grounded Western experience since well before the time of Christ,’ since those very origins of Western thought are unbiblical and idolatrous? Why stop with the Enlightenment? Why is it so unthinkable to Lundin that the Enlightenment is a development out of fundamentally classical roots, that in it we see the logical unfolding of ideas that had been held in an uneasy syncretistic embrace through the many years of medieval Christendom? And, finally, why should we ‘desire to recover or restore those practices and beliefs,’ if they contain within them the very germs of Enlightenment thought?”

Davies’ critical analysis of Lundin is stuck in the nineteenth century American Revivalist Tradition (ART) reading of old-time historiography; an anti-modernist positioning which is not to be found in the credible history discipline today. Schaffer’s hermeneutic worked, though, on the principle that “something could be historically false and religiously true.”[51] I recall back in the early 1980s my teacher in Christian Thought, Ian Gillman, faced with the bubble thinking of Schaefferan apologetic students, pointed out Schaffer’s historiographical account had completely missed engaging with Kant. On the subject of historiography, Schaefferan apologetics is full of cognitive holes.

- Critiques with the Whole Sub-Disciplines of Philosophy and Sociology

The critiques of Schaefferan apologetics from the wide disciplines of philosophy and sociology goes beyond the hermeneutic problem. Often the criticisms relay the failed aesthetic sensibilities of Schaeffer: “Elsewhere, FitzGerald describes Francis Schaeffer’s critique of Renaissance art as ‘a triumph of ideology over the sight of what was in front of him- and a perfectly philistine position that viscerally he did not feel’ (pp. 352-353).”[52]

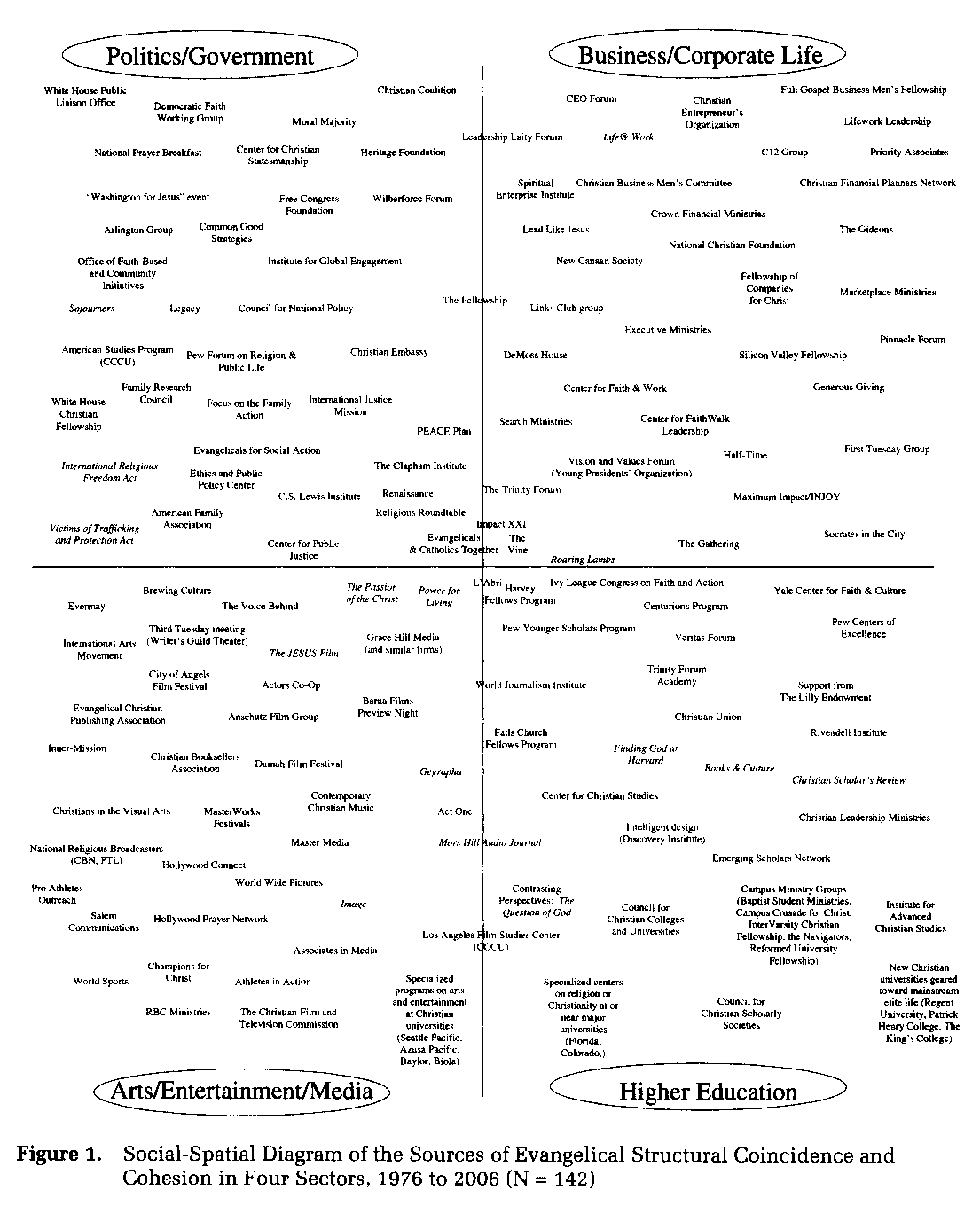

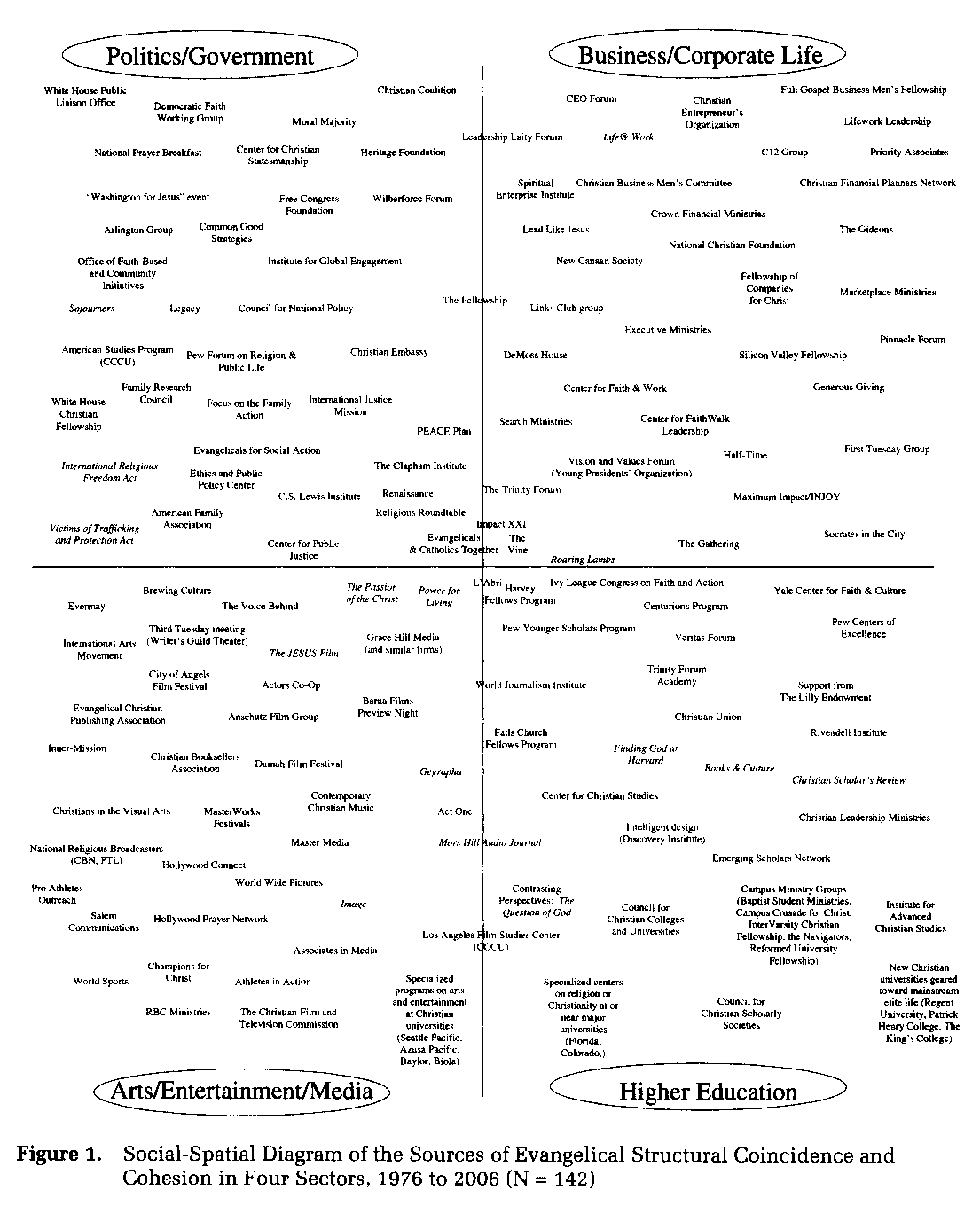

While there is a mass of literature in and of evangelical sociology, very little has been done on the sociology of evangelicalism which picks the significant place of Schaefferan apologetics. Lindsay (2008) is a significant example of what has been achieved.[53] Lindsay’s Figure 1. Social-Spatial Diagram of Evangelical Structural Coincidence and Cohesion in Four Sectors, 1976 to 2006 (n = 142) is important.

- Critiques with the Whole Sub-Disciplines of Philosophy, Ethics, and Language Studies

Several sources identified Schaeffer’s radicalisation in the American anti-abortion, pro-life, movement. Intellectually, it was a turn into moralism after the counter-culture period of the L’ Abri communitarian ethics. That moralism was centred in the virtue concept of “family value”.[54] Since Schaeffer took an inerrant view of biblical language where there was no room for compromise in ethical theory. Morals were absolute. Laws needed to be as absolute as possible but recognising the political convenience of taking what one could get in the legislative and court processes. Here what theory survives the anti-theory approach of Schaeffer is reduced to divine command (theory). It is the morals of a theocracy but could not truly be said to be ethics in respects to the subject (moral subjectivism), persons (personalism), or existential choice (ethical existentialism). Schaeffer does make rhetorical appeals to the concept of a person and subjects of the state, but his anti-humanism with no Christian humanist respect belies his moralistic positioning.

Philosophical-aware historians have picked up that the moralism of the Schaefferan-shaped NCR is driven by historically bare ideas in the obsession with sexuality and sexual reproduction. Moreton (2009) does well to identity the utterly and historically confused language in the Schaeffer and Koop argument:[55]

“In 1979, Christian surgeon – and later United States surgeon general – C. Everett Koop teamed up with the prolific antiabortion crusader Francis A. Schaeffer to produce Whatever Happened to the Human Race? Under this title, a book, a five-part video sequence, and a traveling workshop laid out the winning argument against abortion for Christians who had previously shown little formal concern: rational Enlightenment values – ‘secular humanism’ in the authors’ argot – could not distinguish between vulnerable, unproductive, non-contributing members of the human race and any other drag on maximum efficiency. With the machine as its supreme being, the argument went, perverse, pitiless reason could define people as expendable.”

You would expect to find no such flimsy argument of the NCR in a credible university course on ethics.

Mapping Schaefferan Apologetics in relation to the disciplines

The cross-over disciplinary analysis from academic literature demonstrates that the Schaefferan apologetics and historiography has failed to catch anyone other than the uneducated in the disciplines. The literature is so large (53 articles for this research work alone) that to make the point further the following are others citations, apart from what has already been referenced, and listed as follows:

- “The Lausanne Congress on World Evangelization in 1974 was the largest global gathering of evangelical Christians in the latter half of the twentieth century. Lausanne was significant, in part because of the struggle between two sets of evangelical leaders: those, led by the US, who wanted to retain a focus on ‘evangelism,’ and the young radicals, led by Latin Americans, who demanded a broader attention to ‘social concern.’ This essay traces the impact of the liberalizing faction, while also following the ‘evangelism-first’ movement and its role in the rise of the religious right in the US in the 1980s.”[56]

- “Fundamentalism provides a strong system of social support and a sense of purpose to its participants. An analysis of apostate surveys identified the primary positive attractions of fundamentalism as friendship and family, a sense of purpose, a sense of belonging, a sense of community, and a sense of certainty.”[57]

- [As an Islamic scholar’s critique] “ ‘3. Assault on Liberalism by portraying Secular Humanism as a Religion. The fundamentalists had lost to the modernists at the beginning of the 20th century on the intellectual grounds. Their main problem was that they challenged modern science on the basis of biblical facts as the ultimate truth. In the second half of the 20th century they changed the strategy and instead argued that the liberal ideologues actually believed in secular humanism as a religion. This meant that the liberal worldview and paradigm were actually drawn from the philosophical foundations of secular humanism. This implied that the secular humanism played the same role in liberal thought as religion. This attack on liberalism inspired titles for publications, like The Christian Beacon; Essentialist; Crusader’s Champion; King’s Business; Conflict; Defender; and Dynamited.’ The main architect of this intellectual position was Francis Schaeffer.”[58]

- “Hankins [2008] is fully aware of the overarching trope established by Mark Noll in his now-classic The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1994). The point is that the Evangelical movement did not forget to think; rather, it was a movement meant to do without ideas. Thus, for the subject of the biography, Francis Schaeffer, to try to shape an ‘Evangelical mind’ would be to try to climb a mountain as high as his beloved Swiss Alps, where he labored for many years.” …The author shows Schaeffer as both memorable and problematic in three areas: as a fundamentalist who created fairly narrow boundaries to defend the purity of the church; as a guru of the Christian Right in the United States after about 1980, in which he tried to galvanize a return to America’s putative Christian roots; and as a daring intellectual generalizer who took ideas seriously enough to provide a broad interpretation and critique of Western society… Nevertheless, I join many others in celebrating Francis Schaeffer for getting us underway toward intellectual goals we would probably not have imagined without him. While most of us later transcended his initial vision, it would be churlish of us not to acknowledge with gratitude how we began our journeys…Hankins does mention the dark and unappealing side of Schaeffer’s life (bouts with depression, temper fits, and alleged physical abuse of his wife). The author wisely, in my view, distances his analysis from the tawdry, almost embarrassing, story that has been written about so flamboyantly by Schaeffer’s son, Frank, in his tell-all (and one means all) memoir, Crazy for God: How I Grew Up as One of the Elect, Helped Found the Religious Right, and Lived to Take All (or Almost All) of It Back (Cambridge, MA: De Capo Press, 2007).”[59] [To the discipline critic, the reading of the reviewer seems like he wanted it both ways: salvaging Francis Schaeffer in history and yet the Schaefferan historiography must fall].

- “Moore [2015] opens and concludes his book with a brief critical engagement with the Christian America claims of David Barton, Glenn Beck, and Francis Schaeffer. The main body of the book, however, is set in the past. Founding Sins focuses on the Covenanter variety of Presbyterianism and its influence on American politics. As such, it provides a helpful survey of the Covenanter movement, starting in Scotland, then making its way to the United States. Along the way, the reader is treated to Presbyterian church history, political intrigue of the English monarchy, American colonial history, and a fascinating look at the often contradictory nature of nineteenth-century moral and social activism.”[60] [b. contradictory because of contemporary reading and belief in the nineteenth century historiography and ART]

- “A well-functioning democracy is dependent on truth itself. Trump’s efforts to undermine the press, undermine the availability and credibility of truth, threatens the foundations of American democracy. As previously stated, the Fourth Estate exists outside the dominion of the Executive Branch to prevent this very phenomenon from paralyzing the nation. Through his calculated disregard of object truth, he has managed to further polarize the opposite ends of the political spectrum. … It seems that now political discussion has regressed so far that Democrats and Republicans cannot even manage to get on the same page about basic facts. When the truth is made out to be “liberal conspiracy theories,” all constructive dialogue begins to break down.”[61] [not directly related to Schaeffer, but Schaeffer’s apologetics is caught up in the semantics of the observation]

In Kevin Schilbrack’s paper, ‘The Study of Religious Belief after Donald Davidson’ (2002) is a demonstration that Christian apologetics is far too removed from the philosophy discipline to make any sense today (outside of populist ignorance).[62] As Schilbrack explained, Davidson famously argued for the incoherence of what he calls scheme/content dualism. What is criticised is the view that thought can be divided into two parts: a conceptual system that our mind or our language provides and the preconceptual content that the world provides. Davidson argument targets the Kantian concept of noumena, and this might trouble propositions of liberal Christianity; that is contested. What is not contested is that Schaefferan apologetics has no capacity to deal with Davidson. Liberal Christianity may or may not be defeated in such an argument, but certainly evangelicalism which relies on conservative thought is. It is simply not that Schaefferan apologetics is a Wittgenstein ladder that can be kicked away for evangelical apologetics to continue as if it can ignore wider debates in the disciplines. And for this reason, evangelical believers need to abandon apologetics and return to the disciplines. The better evangelical scholars, such as George Marsden, Mark Noll, and Alvin Plantinga, always have and they three are distinctive as the evangelical scholarship associated with Notre Dame University.

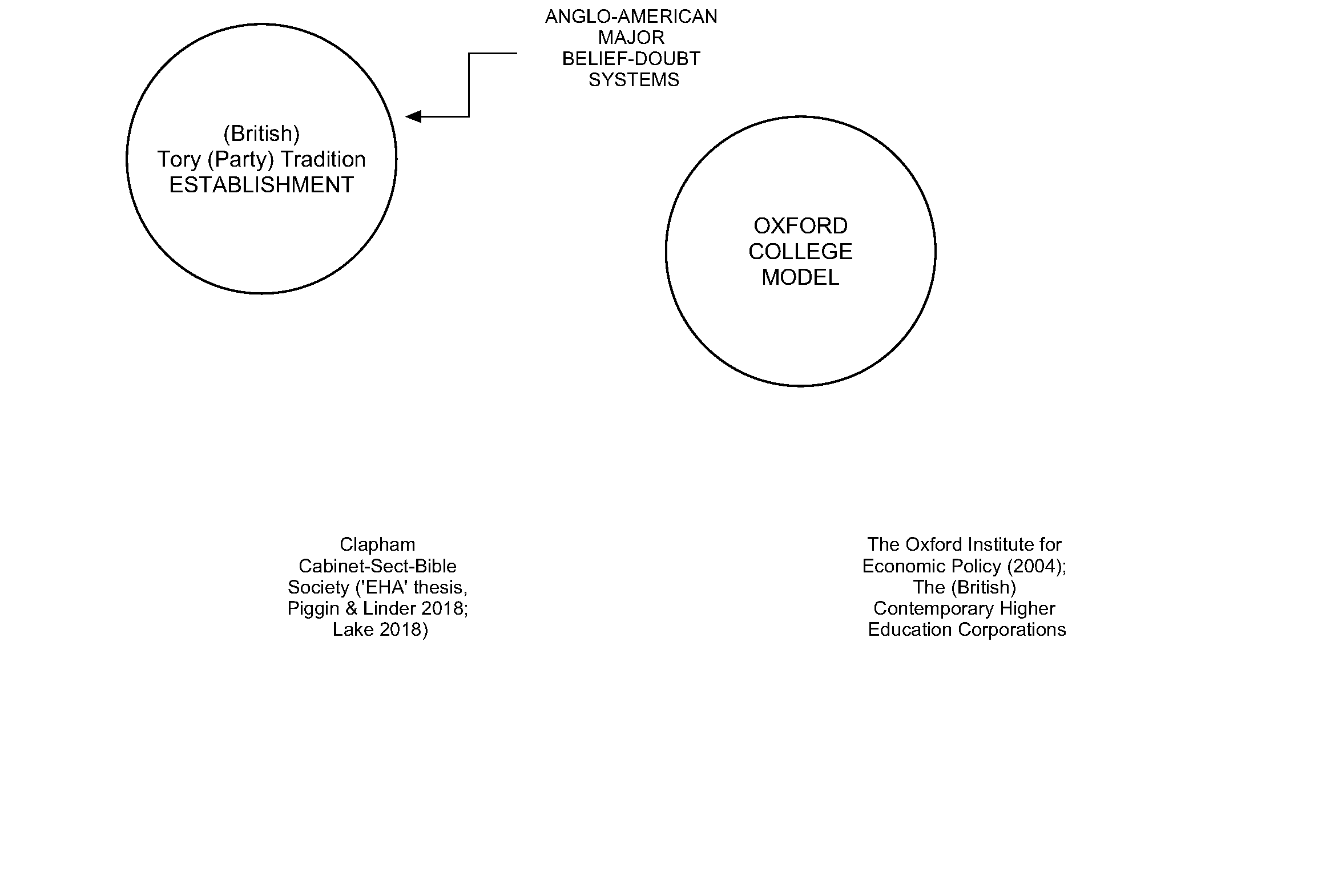

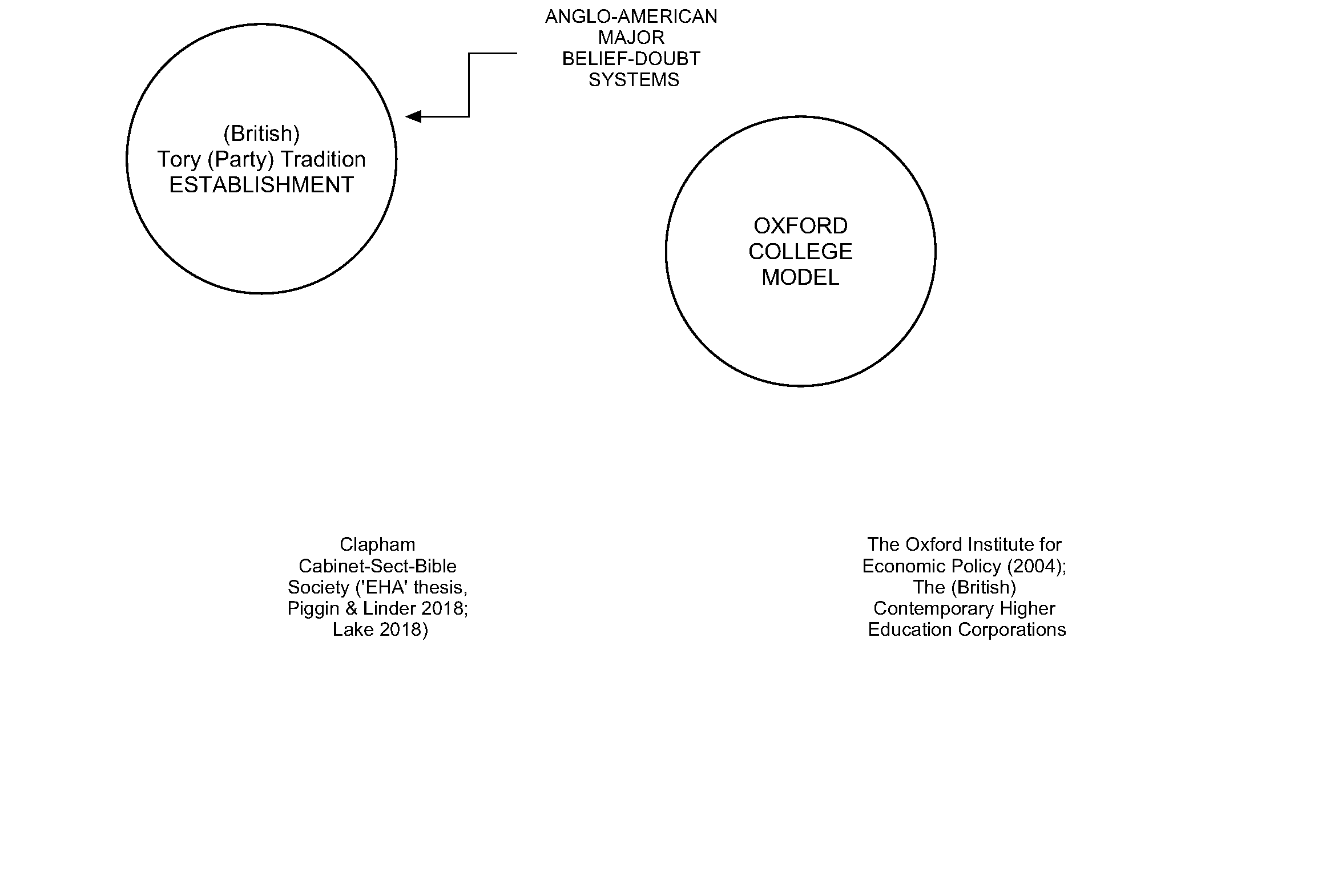

For the institutional rest, the intellectual problems illustrated as reference in the Buch’s Mapping the World of Schaefferan apologetics (as apologetics, not disciplinary knowledge; distinguishing roles of Plantinga, who appears on the graph, between the philosopher and used in apologetics).

There are many others who are in that world but are not listed here, such as Udo Middelmann, the President of the Francis A. Schaeffer Foundation. The point of the graph is that Schaeffer’s thinking is directed through several disciplinary filters and connects up to American activists and public intellectuals. Before his death in 1984, Schaeffer shaped their thinking, and they Schaeffer’s. Many are NCR players, but several important figures are not. Other figures, such as Cornelius Van Til, demonstrate the role of pre-propositional apologetics.[63] The commonality is the lost credibility in, or of Schaefferan historiography. In Schaefferan historiography, nearly all philosophic schemas are lost; Plantinga’s Warrant Belief and proper function maybe an exception, but it is not enough to save apologetics. The argument of warrant belief and proper function is the epistemic glue in the argument for abandoning apologetics for discourse in disciplinary knowledge. So, what went wrong? Schaefferan historiography is based in the thinking of Empiricalistic-Institutional driven school of history which had existed at the time of the Biblicalist Charles Hodge (1797-1878). In Schaeffer’s anti-modernism critical-thinking historiography was lost to him.

REFERENCE LIST

Publication List: Recent back to the Buch ART Thesis in 1994-1995.

Miller, Paul D. (2022). The Religion of American Greatness: What’s Wrong With Christian Nationalism, IVP Academic.

Curtis, Jesse (2021). The Myth of Colorblind Christians: Evangelicals and White Supremacy in the Civil Rights Era, New York University Press.

Hendricks Jr., Obery M. (2021). Christians Against Christianity: How Right-Wing Evangelicals are Destroying our Nation and our Faith, Boston: Beacon Press.

Weinberg, C. R. (2021). Trees, Knees, and Nurseries. In Red Dynamite: Creationism, Culture Wars, and Anticommunism in †America (pp. 202–246). Cornell University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctv310vk3m.10

Weinberg, C. R. (2021). The Nightcrawler, the Wedge, and the Bloodiest Religion. In Red Dynamite: Creationism, Culture Wars, and Anticommunism in †America (pp. 247–270). Cornell University Press. http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.7591/j.ctv310vk3m.11

Du Mez, Kristin Kobes (2020). Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Fractured a Nation, New York: Liveright Publishing Corporation

Brooke McPherson, & Helen McGowan. (2020). The Reality of Fake News, A Study of Donald J. Trump’s Free Press Violations [Documents]. https://jstor.org/stable/community.28786802

Miller, S. P. (2019). [Review of The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America, by F. FitzGerald]. The North Carolina Historical Review, 96(4), 449–450. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45286369

Wilson, J. C., & Hollis-Brusky, A. (2018). Higher Law: Can Christian Conservatives Transform Law Through Legal Education? Law & Society Review, 52(4), 835–870. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45093945

MCALISTER, M. (2017). The Global Conscience of American Evangelicalism: Internationalism and Social Concern in the 1970s and Beyond. Journal of American Studies, 51(4), 1197–1220. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26803498

Coffman, E. (2017). [Review of Saving Faith: Making Religious Pluralism an American Value at the Dawn of the Secular Age, by D. Mislin]. The Journal of Religion, 97(4), 576–578. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26544108

Balmer, R., Bowler, K., Butler, A., Farrelly, M. J., Markofski, W., Orsi, R., Park, J. Z., Davidson, J. C., Sutton, M. A., & Yukich, G. (2017). Forum: Studying Religion in the Age of Trump. Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation, 27(1), 2–56. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26419415

Hankins, B. (2016). [Review of American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism, by M. A. Sutton]. The Journal of Religion, 96(4), 581–582. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26543598

Dowland, S. (2016). Making Sense of Twentieth-Century American Evangelicalism [Review of The Age of Evangelicalism: America’s Born-Again Years; American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism; Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism, by S. P. Miller, M. A. Sutton, & M. Worthen]. Reviews in American History, 44(1), 152–159. http://www.jstor.org/stable/26363998

Keene, T. (2016). Kuyper and Dooyeweerd: Sphere Sovereignty and Modal Aspects. Transformation, 33(1), 65–79. https://www.jstor.org/stable/90008856

Kersch, K. I. (2016). Constitutive Stories about the Common Law In Modern American Conservatism. Nomos, 56, 211–255. https://www.jstor.org/stable/26387884

Doenecke, J. D. (2015). [Review of The Twilight of the American Enlightenment: The 1950s and the Crisis of Liberal Belief; Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism, by G. M. Marsden & M. Worthen]. Anglican and Episcopal History, 84(4), 496–498. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43685184

Harp, Gillis J. Church History 84, no. 3 (2015): 701–4. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24537399.

Noll, M. A. (2015). [Review of The Age of Evangelicalism: America’s Born-Again Years, by S. P. Miller]. The American Historical Review, 120(2), 674–675. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43696800

Kidd, T. S. (2015). [Review of Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism, by M. Worthen]. Church History, 84(1), 276–278. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24537327

Doenecke, J. D. (2015). [Review of The Twilight of the American Enlightenment: The 1950s and the Crisis Liberal Belief; Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism, by G. M. Marsden & M. Worthen]. Anglican and Episcopal History, 84(1), 93–95. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43685088

Nijhoff, R. (2015). [Review of Neo-Calvinism and Christian Theosophy. Franz von Baader, Abraham Kuyper, Herman Dooyeweerd, by J. G. Friesen]. Philosophia Reformata, 80(2), 236–240. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24709980

Moore, Joseph S. (2015). Founding Sins: How a Group of Antislavery Radicals Fought to Put Christ into the Constitution. New York: Oxford University Press.

Worthen, Molly (2014). Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism, Oxford University Press.

Marsden, George M. (2014). The Twilight of the American Enlightenment: The 1950s Liberal Belief, New York: Basic Books.

Fauci, A. S. (2014). C. Everett Koop: 14 October 1916 · 25 February 2013. Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, 158(4), 455–460. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24640191

Lempke, M. A. (2014). So Long, Jerry Falwell: Reconsidering Evangelical Public Engagement [Review of The Anointed: Evangelical Truth in a Secular Age; Moral Minority: The Evangelical Left in an Age of Conservatism, by R. J. Stephens, K. W. Giberson, & D. R. Swartz]. Reviews in American History, 42(1), 174–180. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43663494

Ruotsila, M. (2013). “Russia’s Most Effective Fifth Column”: Cold War Perceptions of Un-Americanism in US Churches. Journal of American Studies, 47(4), 1019–1041. http://www.jstor.org/stable/24485873

Fea, J. (2013). Using the Past to “Save” Our Nation: The Debate over Christian America. OAH Magazine of History, 27(1), 7–11. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23489627

Groothuis, D. (2013). [Review of Abraham Kuyper. A Short and Personal Introduction, by R. J. Mouw]. Church History and Religious Culture, 93(4), 638–640. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23923543

Ruotsila, M. (2012). Carl McIntire and the Fundamentalist Origins of the Christian Right. Church History, 81(2), 378–407. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23253819

Northcott, M. S. (2012). READING HAUERWAS IN THE CORNBELT: The Demise of the American Dream and the Return of Liturgical Politics. The Journal of Religious Ethics, 40(2), 262–280. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23251026

Swartz, D. R. (2011). Identity Politics and the Fragmenting of the 1970s Evangelical Left. Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation, 21(1), 81–120. https://doi.org/10.1525/rac.2011.21.1.81

Krabbendam, H. (2011). [Review of Francis Schaeffer and the Shaping of Evangelical America, by B. Hankins]. Church History and Religious Culture, 91(3/4), 606–608. http://www.jstor.org/stable/23922883

Lofton, K. (2010). [Review of Francis Schaeffer and the Shaping of Evangelical America. Library of Religious Biography Series, by B. Hankins]. Church History, 79(4), 983–985. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40962918

Wells, R. A., & Hankins, B. (2010). [Review of Francis Schaeffer and the Shaping of Evangelical America]. The Journal of Religion, 90(3), 417–419. https://doi.org/10.1086/654862

Ingersoll, J. (2009). [Review of Francis Schaeffer and the Shaping of Evangelical America, by B. Hankins]. The Journal of American History, 96(2), 611–611. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25622435

Dowland, S. (2009). “Family Values” and the Formation of a Christian Right Agenda. Church History, 78(3), 606–631. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20618754

Moreton, B. (2009). Why Is There So Much Sex in Christian Conservatism and Why Do So Few Historians Care Anything about It? The Journal of Southern History, 75(3), 717–738. http://www.jstor.org/stable/27779035

Worthen, M. (2008). The Chalcedon Problem: Rousas John Rushdoony and the Origins of Christian Reconstructionism. Church History, 77(2), 399–437. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20618492

Lindsay, D. M. (2008). Evangelicals in the Power Elite: Elite Cohesion Advancing a Movement. American Sociological Review, 73(1), 60–82. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25472514

Adam, R. (2008). Relating Faith Development and Religious Styles: Reflections in Light of Apostasy from Religious Fundamentalism. Archiv Für Religionspsychologie / Archive for the Psychology of Religion, 30, 201-231. Retrieved April 29, 2020, from www.jstor.org/stable/23907899

McGreevy, J. (2007). Catholics, Democrats, and the GOP in Contemporary America. American Quarterly, 59(3), 669–681. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40068445

Grams, R. G. (2007). Transformation Mission Theology: Its History, Theology and Hermeneutics. Transformation, 24(3/4), 193–212. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43052710

Perlstein, R. (2006). Thunder on the Right: The Roots of Conservative Victory in the 1960s. OAH Magazine of History, 20(5), 24–27. http://www.jstor.org/stable/25162080

Freedman, R. (2005). The Religious Right and the Carter Administration. The Historical Journal, 48(1), 231–260. http://www.jstor.org/stable/4091685

Butler, J. (2004). Jack-in-the-Box Faith: The Religion Problem in Modern American History. The Journal of American History, 90(4), 1357–1378. https://doi.org/10.2307/3660356

ZAKAULLAH, M. A. (2003). The Rise of Christian Fundamentalism in the United States and the Challenge to Understand the New America. Islamic Studies, 42(3), 437–486. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20837287

Carpenter, J. (2003). [Review of The Book of Jerry Falwell: Fundamentalist Language and Politics, by S. F. Harding]. The Journal of Religion, 83(1), 124–125. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1205452

Jerry Falwell. (2003). Our Dying Values [Documents]. https://jstor.org/stable/community.32095064

Appleby, R. S. (2002). History in the Fundamentalist Imagination. The Journal of American History, 89(2), 498–511. https://doi.org/10.2307/3092170

Schilbrack, Kevin (2002). The Study of Religious Belief after Donald Davidson, Method &# 38; Theory in the Study of Religion, ingentaconnect.com, https://www.academia.edu/1964361/The_Study_of_Religious_Belief_after_Donald_Davidson

Nord, W. A. (2001). [Review of Standing on the Premises of God: The Christian Right’s Fight to Redefine America’s Public Schools, by F. Detwiler]. The Journal of Religion, 81(3), 471–472. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1206420

Jeffrey, D. L. (2000). C. S. Lewis, the Bible, and Its Literary Critics. Christianity and Literature, 50(1), 95–109. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44298997

Hamil-Luker, J., & Smith, C. (1998). Religious Authority and Public Opinion on the Right to Die. Sociology of Religion, 59(4), 373–391. https://doi.org/10.2307/3712123

Ahdar, R. J. (1998). A Christian State? Journal of Law and Religion, 13(2), 453–482. https://doi.org/10.2307/1051480

Davies, L. (1997). Covenantal Hermeneutics and the Redemption of Theory. Christianity and Literature, 46(3/4), 357–397. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44312553

Burson, S. R. (1996). A Comparative Analysis of C. S. Lewis and Francis Schaeffer — The Most Influential Apologists of Our Time. The Lamp-Post of the Southern California C.S. Lewis Society, 20(2), 4–29. http://www.jstor.org/stable/45348286

Appleby, S. (1996). [Review of Redeeming America: Piety and Politics in the New Christian Right, by M. Lienisch]. Church History, 65(1), 168–169. https://doi.org/10.2307/3170573

Steffen, L. (1995). [Review of The Politics of Virtue: Is Abortion Debatable? by E. Mensch & A. Freeman]. Journal of the American Academy of Religion, 63(4), 910–914. http://www.jstor.org/stable/1465491

Pierard, R. (1995). Civil Religion Critically Revisited. Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte, 8(1), 203–219. http://www.jstor.org/stable/43096664

Noll, Mark A. (1994). The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, Grand Rapids: William B. Eermans Publishing Company.

Lienisch, Michael (1993). Redeeming America: Piety and Politics in the New Christian Right. Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina.

Marsden, George M. (1987). Reforming Fundamentalism. Fuller Seminary and the New Evangelicalism, Grand Rapids: William B. Eermanns Publishing Company.

Marsden, George M. (1980). Fundamentalism and American Culture: The Shaping of Twentieth Century Evangelicalism 1870-1925, New York. Oxford University Press.

FOOTNOTES

[1] Marsden, George M. (1987). Reforming Fundamentalism. Fuller Seminary and the New Evangelicalism, Grand Rapids: William B. Eermanns Publishing Company, Pages 44, 100n16, 105n32, 111, 113.

[2] Lofton, K., 2010, Review of Francis Schaeffer and the Shaping of Evangelical America, Church History, Issue 79, 983–985. Cited page 984.

[3] Ruotsila, M., 2012, Carl McIntire and the Fundamentalist Origins of the Christian Right, Church History, Issue 81, 378–407. “Jerry Falwell was greatly influenced by the eventual embrace of Mclntire style civil disobedience by Francis Schaeffer—who, of course, was Mclntire’s old student and protege, the first pastor ordained in the Bible Presbyterian Church and the ACCC’s chief European representative in the late 1940s and the early 1950.” Page 394.

[4] Worthen, Molly, 2014, Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism, Oxford University Press. Pages 209-19, 212, 228-9, 231, 240, 251, 260, 311n18.

[5] Nord, W. A., 2001, Review of Standing on the Premises of God: The Christian Right’s Fight to Redefine America’s Public Schools, The Journal of Religion, Issue 81, 471–472. Quotation page 472.

[6] Freedman, R., 2005, The Religious Right and the Carter Administration, The Historical Journal, Issue 48, 231–260. Quotation page 234. Susan Friend Harding (2000). The book of Jerry Falwell: fundamentalist language and politics, Princeton, NJ.

[7] Noll, Mark A., 1994, The Scandal of the Evangelical Mind, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, page 223.

[8] Noll, M. A., 2015, Review of The Age of Evangelicalism: America’s Born-Again Years, The American Historical Review, Issue 120, 674–675. See the description page 674.

[9] Jerry Falwell., 2003, Our Dying Values [Documents]. Email from Jerry Falwell, dated 2 July 2003.

[10] Lempke, M. A., 2014, Review of The Anointed: Evangelical Truth in a Secular Age, Reviews in American History, Issue 42, 174–180. Cited page 179.

[11] Grams, R. G., 2007, Transformation Mission Theology: Its History, Theology and Hermeneutics, Transformation, Issue 24, 193–212. Specially page 97.

[12] Appleby, R. S., 2002, History in the Fundamentalist Imagination, The Journal of American History, Issue 2, 498–511. Quotations on pages 503-4, and 505.

[13] Butler, J., 2004, Jack-in-the-Box Faith: The Religion Problem in Modern American History, The Journal of American History, Issue 4, 1357–1378. Quotation page

[14] Doenecke, J. D., 2015, Review of The Twilight of the American Enlightenment: The 1950s and the Crisis of Liberal Belief, Anglican and Episcopal History, Issue 84, 496–498. Quotation page 497.

[15] Swartz, D. R., 2011, Identity Politics and the Fragmenting of the 1970s Evangelical Left, Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation, Issue 21, 81–120. Quotation pages 88-89.

[16] For example, Nijhoff, R., 2015, Review of Neo-Calvinism and Christian Theosophy. Franz von Baader, Abraham Kuyper, Herman Dooyeweerd, Philosophia Reformata, Issue 80, 236–240.

[17] Groothuis, D., 2013, Review of Abraham Kuyper. A Short and Personal Introduction, by R. J. Mouw. Church History and Religious Culture, 93, Church History and Religious Culture, Issue 93, 638–640. Quotation page 639.

[18] Keene, T., 2016, Kuyper and Dooyeweerd: Sphere Sovereignty and Modal Aspects, Transformation, Issue 33, 65–79. Cited page 69.

[19] Fea, J., 2013, Using the Past to “Save” Our Nation: The Debate over Christian America, OAH Magazine of History, Issue 27, 7–11. Specifically, page 9.

[20] Some in the literature put Schaeffer in the premillennial camp, such as Worthen, Molly, 2014, Apostles of Reason, 304-5n32. But that it hard to comprehend when premillennialism is essentially the escaping worldly affairs at the Return of Christ. It would be proper to describe Schaefferan apologetics postmillennial since as Perlstein (2006) stated, “that Jesus would never come back until iniquity was conquered on earth,” a clearly postmillennial position.

[21] Perlstein, R., 2006, Thunder on the Right: The Roots of Conservative Victory in the 1960s, OAH Magazine of History, Issue 20, 24–27. Quotation page 27.

[22] For example, Kidd, T. S., 2015, Review of Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism, Church History, Issue 84, 276–278. Kidd refers to the movement and its anxieties it raises.

[23] Ingersoll, J., 2009, Review of Francis Schaeffer and the Shaping of Evangelical America, The Journal of American History, Issue 96, 611–611. Barry Hankins (2008). Francis Schaeffer and the Shaping of Evangelical America, Grand Rapids: Eerdmans. Citations pages 611

[24] Doenecke, J. D., 2015, Review of Apostles of Reason: The Crisis of Authority in American Evangelicalism, Anglican and Episcopal History, Issue 84, 93–95. Quotation page 94.

[25] Dowland, S., 2016, Review of The Age of Evangelicalism: America’s Born-Again Years, Reviews in American History, Issue 44, 152–159. Quotation page 156.

[26] Wilson, J. C., & Hollis-Brusky, A., 2018, Higher Law: Can Christian Conservatives Transform Law Through Legal Education? Law & Society Review, Issue 52, 835–870. Cited page 843.

[27] Ahdar, R. J., 1998, A Christian State? Journal of Law and Religion, Issue 2, 453–482. Quotation on pages 464 and 467.

[28] Krabbendam, H., 2011, Review of Francis Schaeffer and the Shaping of Evangelical America, Church History and Religious Culture, Issue 91, 606–608. Quotation page 607.

[29] Appleby, S., 1996, Review of Redeeming America, Church History, Issue 1, 168–169. “Lienisch recognizes that the NCR is a social movement complex intellectual and moral claims at its core. Intellectual historians appreciate his refusal to subordinate beliefs and values other reliable but overplayed markers of social identity. This approach raises a formidable theoretical challenge, however, in assuming tease out a coherent worldview from the several, often somewhat ambivalent opinions, theologies, and historical various personalities normally identified with the movement. To complicate things further, Lienisch rightly included not only politicized preachers (Pat Robertson and Jerry Falwell), preachy politicians (Jesse Helms), celebrity evangelicals (Anita Bryant and in-house movement intellectual (Francis Schaeffer) – but also the dozens of lesser-known (to outsiders) but influential ideologues such David Chilton, George Grant, John Eidsmore, and Rousas John Rushdoony.” Appleby 1996: 168. Lienisch, Michael (1993). Redeeming America: Piety and Politics in the New Christian Right. Chapel Hill, N.C.: The University of North Carolina.

[30] Balmer, R., Bowler, et al., 2017, Forum: Studying Religion in the Age of Trump. Religion and American Culture, Religion and American Culture: A Journal of Interpretation, Issue 1, 2–56. Cited on page 6.

[31] Carpenter, J., 2003, Review of The Book of Jerry Falwell: Fundamentalist Language and Politic, The Journal of Religion, Issue 1, 124–125. “With the help of the Calvinist preacher and apologist Francis Schaeffer, Falwell gets his world-fleeing fundamentalists to imagine a greater role in God’s grand economy as world transformers. The immediate object of their reforming witness is America it.” Pages 124-5.

[32] Kersch, K. I., 2016, Constitutive Stories about the Common Law in Modern American Conservatism, Nomos, Issue 56, 211–255. Cited pages 227-8, 250. Rushdoony, Rousas John (1973). The Institutes of Biblical Law, Nutley, NJ: P&R (Craig Press)

[33] Worthen, M., 2008, The Chalcedon Problem: Rousas John Rushdoony and the Origins of Christian Reconstructionism, Church History, Issue 77, 399–437. Quotation page 435.

[34] Du Mez, Kristin Kobes, 2020, Jesus and John Wayne: How White Evangelicals Corrupted a Faith and Frac-tured a Nation, Liveright publishing Corporation. Cite page 78.

[35] Hankins, B., 2016, Review of American Apocalypse: A History of Modern Evangelicalism, The Journal of Religion, Issue 96, 581–582. Quotation page 582.

[36] Harp, Gillis J., 2015, Review of Republican Theology: The Civil Religion of American Evangelicals, Church History, Issue 84, 701-4. Cited page 703.

[37] Weinberg, C. R., 2021, Trees, Knees, and Nurseries, in Creationism, Culture Wars, and Anticommunism in †America, Cornell University Press. Specially, pages from 204 to 232.

[38] McGreevy, J., 2007, Catholics, Democrats, and the GOP in Contemporary America, American Quarterly, Issue 59, 669–681. Cited page 672.

[39] Noll, M. A., 2015, Review of The Age of Evangelicalism: America’s Born-Again Years, The American Historical Review, 120, 674-675. Cited 674.

[40] Northcott, M. S., 2012, Reading Hauerwas in The Cornbelt: The Demise of the American Dream and the Return of Liturgical Politics, The Journal of Religious Ethics, Issue 40, 262–280. Quotation page 264.

[41] Pierard, R., 1995, Civil Religion Critically Revisited, Kirchliche Zeitgeschichte, Issue 8, 203–219. Quotation page 216.

[42] Miller, Paul D., 2022, The Religion of American Greatness: What’s Wrong With Christian Nationalism. Pages 21-22, 143, 148-9.

[43] Ruotsila, M., 2013, “Russia’s Most Effective Fifth Column”: Cold War Perceptions of Un-Americanism in US Churches, Journal of American Studies, Issue 47, 1019–1041. Quotation page 1028. 8); Schaeffer, Francis. (1950) The New Modernism, Philadelphia: The Independent Board of Presbyterian Foreign Missions.

[44] Fauci, A. S., 2014, C. Everett Koop: 14 October 1916-25 February 2013, Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society, Issue 158, 455–460.

[45] Hamil-Luker, J., & Smith, C., 1998, Religious Authority and Public Opinion on the Right to Die, Sociology of Religion, Issue 59, 373–391. Quotation page 387.

[46] Weinberg, C. R., 2021, Trees, Knees, and Nurseries, in Creationism, Culture Wars, and Anticommunism in †America, Cornell University Press. Quotation page 250.

[47] Steffen, L., 1995, Review of The Politics of Virtue: Is Abortion Debatable? Journal of the American Academy of Religion, Issue 63, 910–914. Quotation page 913.

[48] Burson, S. R., 1996, A Comparative Analysis of C. S. Lewis and Francis Schaeffer, The Lamp-Post of the Southern California C.S. Lewis Society, Issue 2, 4–29. References are pages 14-18.

[49] Jeffrey, D. L., 2000, C. S. Lewis, the Bible, and Its Literary Critics, Christianity and Literature, Issue 50, 95–109. Cited page 97.

[50] Davies, L., 1997, Covenantal Hermeneutics and the Redemption of Theory, Christianity and Literature, Issue 46, 357–397. Quotation pages 367-8.

[51] Lofton, K., 2010, Review of Francis Schaeffer and the Shaping of Evangelical America, Church History, Issue 79, 983–985. Cited page 984.

[52] Miller, S. P., 2019, Review of The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America, The North Carolina Historical Review, Issue 96, 449–450. Quotation page 449. FitzGerald, Frances (2017). The Evangelicals: The Struggle to Shape America, New York: Simon and Schuster.

[53] Lindsay, D. M., 2008, Evangelicals in the Power Elite: Elite Cohesion Advancing a Movement, American Sociological Review, Issue 73, 60–82. Reference pages 70-1.

[54] Dowland, S., 2009, “Family Values” and the Formation of a Christian Right Agenda, Church History, Issue 78, 606–631. “Schaeffer concluded that ‘we must stand against the loss of humanness in all its forms.’ He saw abortion as murder of innocents, and his book popularized that interpretation among conservative Protestant.” Page 613.

[55] Moreton, B., 2009, Why Is There So Much Sex in Christian Conservatism and Why Do So Few Historians Care Anything about It? The Journal of Southern History, Issue 75, 717–738. Quotation page 723.

[56] McAlister, M., 2017, The Global Conscience of American Evangelicalism: Internationalism and Social Concern in the 1970s and Beyond, Journal of American Studies, Issue 51, 1197–1220. Quotation page 1197.