Evangelicals offer a providential worldview, that centres on evangelical message(s) of the promise to have special access to God, and beyond that, that they – each member of God’s Kingdom – enjoy special access to God, as revelatory knowledge, through the person of the Holy Spirit. Outside of the evangelical bubble, persons find such claims and testimonies of that experience and promise, bizarre. This weekend I have had the revelatory moment where I fully agree with the many, outside the enclosed pathway of the Evangelical person. The path may be narrow for each person, but we must assess the Life journey and its many directions fairly and openly (at least to ourselves).

My current revelatory moment goes to my first break with evangelicalism in 1994-1995. As a new professional historian with a new Ph.D. on the American Revivalist Tradition, I had challenged the providential worldview of believers in 1995. Few took notice then. Professor Timothy Larsen of Wheaton College, on last Saturday (20 May 2023) at the 2023 EHA Conference, spoke about the game-playing in the Evangelical World. Enforced upon them in the historical shift into 20th century modernism, Evangelical believers in the scholarly enterprise, and honest to the academic game (and unfortunately it is an academic game all-round), must take their research and writing into the “non-providential” outlook, but, when the opportunity for public ‘witness’ or for personal ‘testimony’ appears, their true position of the providential outlook is revealed. The immediate problem here is the binary of providential and the bland reference to “non-providential”, but let me take this problem up further on.

This Neo-Evangelical game playing is aligned to another story; one I have described before. It is not exactly the same game playing but related. As a student at Alcorn College in the early 1980s there was a Neo-Fundamentalist game being played. Rev. Col Warren, the Principal and a creationist, was having closed conversations with conservative evangelical students. He encouraged them to be silent of their true intellectual convictions in the university classroom. They could perform their humanities or science studies without protest and to write what was required by the university teachers and supervisor, in order to gain academic accreditation for their apologetic work, outside the academy. The tactic was framed in Neo-Fundamentalism, but make no mistake, this was one strategy of the wider evangelical cultural-history war. Here I have to remind myself to make terms clear; which has been natural to me as a historian of belief and doubt for over 30 years. Fundamentalism is the position that the Bible (semantically the evangelical message) is inerrant and infallible. Neo-Evangelicalism was the break with this position to claim the Bible, with the exact same semantics, highly inspired (the Word of God). Neo-Fundamentalism retained the same early twentieth century positioning of its forebears but added a new hermeneutics – compromising, with the Neo-Evangelicals, in moderate and controlled biblical criticism scholarship. In the case of Neo-Fundamental believers, such efforts deconstructed modernism badly as a history and sociology, arriving at semantically thin forms. For those outside of the academic world, I have to explain the existence of phony debates. The Theism-Atheism debates are mostly phony debates from both sides. The participants cannot fully read – history and sociology – their opposition within their own particular bubble thinking (from both sides). If they could, the realisation would happen that debates are no good, and open and communicative rationality (Habermas 1991-2010 listed) is the only answer.

To return to the concept of the revelatory moment. In 1995, having completed the doctorate and it awarded, I begun the Brisbane Unitarian-Universalist Fellowship, with Ruth (Social Worker), now my late wife, and John (Science Master) and Kelly (Psychologist) Dixon. We individually arrived at our revelatory moment in the great intellectual and spiritual dissatisfaction with evangelicalism. We were quickly joined by American friends, and by Australians commonly in relations to American persons. In my way of thinking, Unitarian-Universalism was the sufficient challenge to the intellectual and spiritual problems in evangelicalism. What is evangelicalism? The historian David Bebbington in 1989 gave the modern quadrilateral definition: the Bible (Biblicism), the Cross (Crucicentrism), the Salvation (Conversionism), and the Spirit (ideas of ‘second blessing’) or Activism (e.g., social justice). Make no mistakes: these positionings are orthodoxies, meaning there are no semantic compromises in belief. Challenge any one orthodox position and you are out on the street and out on your head. Most Evangelical believers will also respond in true kindness, with an honest concern for your soul and wellbeing; but it is an upsetting moment which might lead to a crisis of faith. Conversionism is then a particularly interesting position. Religious conversion is the adoption of a set of beliefs identified with one particular religious denomination to the exclusion of others. Thus ‘religious conversion’ would describe the abandoning of adherence to one former ‘denomination’ (think of this term widely, ‘to denominate loyalty’), or to one former worldview, and affiliating with another. Here Unitarian-Universalism is different. Unitarian-Universalism is a liberal religion characterized by a ‘free and responsible search for truth and meaning’. There might be revelatory moments but there is no conversion experience. As a scholar in history, sociology, and philosophy, I kept my openness. I am still strongly associated with beliefs of Unitarian-Universalism, but I would be only too pleased to criticise the positioning. Foremost, the Unitarian-Universalism has not dealt with the problem of religion which emerges from the scholarly literature of studies-in-religion primarily, and other sources in secondary analysis.

Let’s return to the bland evangelic reference of “non-providential”. It is difficult to find a term which is the opposite of providential and is multi-disciplinary. The best that can be done are disciplinary terms. In theology we find Don Cupitt’s use of the “Everyday” (2011) and Solar Ethics (2000). There is structural historiography in Cupitt but his conception of the everyday (speech) and ethics are not providential. Providence is a construction of history as all history is constructed. Providentia is a divine personification of the ability to foresee and make provision in ancient Roman religion. There is a non-realist sense, though, Cupitt does articulate providential historiography: in his The Meaning of the West: An Apologia for Secular Christianity (2008). It is clearly the providence of Western thinking as a whole. In Jesus and Philosophy (2009), Cupitt does has it half and half, a philosophy of Jesus which is “non-providential”, although a perennial theme (‘the message of Jesus’) in philosophy which is providential as a construction of history, casting back in a linear story of western philosophy.

Now, evangelicalism opposes this understanding of historiography. For one reason, Cupitt’s positioning comes out of a wider ‘Death of God’ movement. However, the problem is not merely one of evangelicalism, but goes to the problem of the religion paradigm. Providence (officially Christian Gospel Mission), better known as JMS (acronym of Jesus Morning Star), is a Christian new religious movement founded by Jung Myung-seok in 1980 and headquartered in Wol Myeong-dong, South Korea. Providence has been widely referred to by international media as a cult (i.e., a particular way of understanding ‘religion’). I will return to the challenge to the providential outlook in the conclusion.

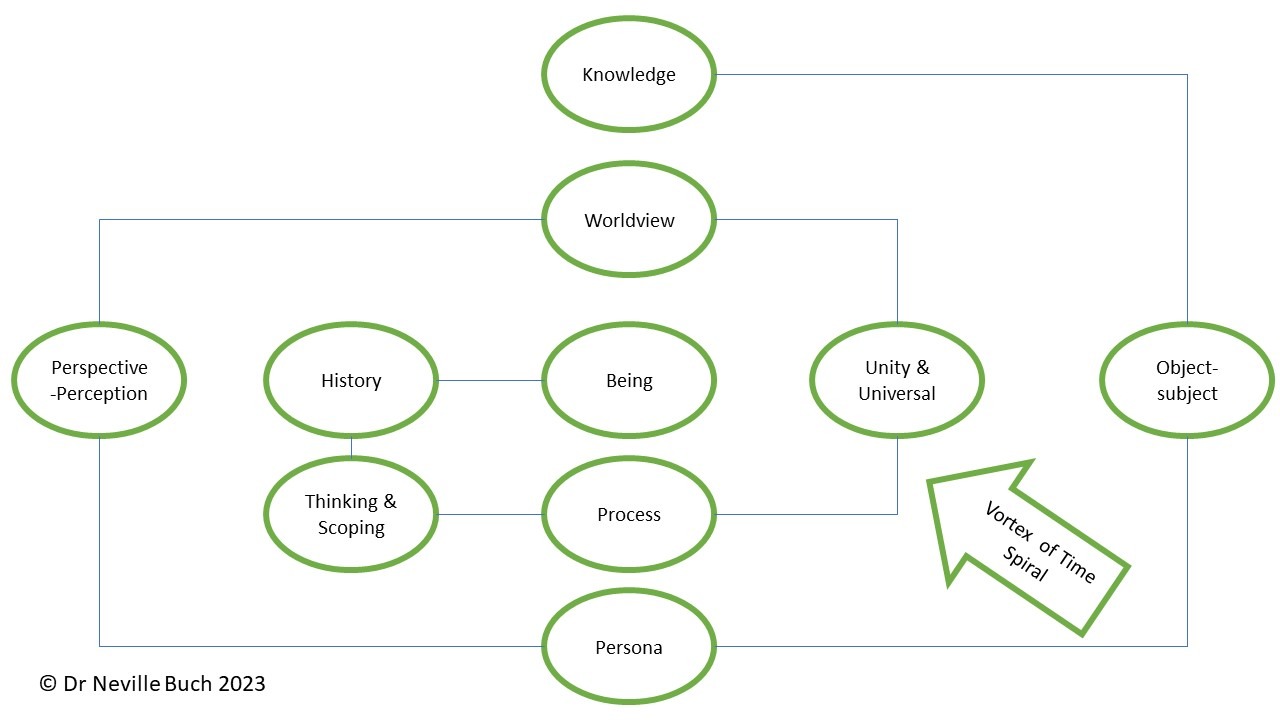

Image: Dr Neville Buch Methodological Model.

The aesthetic analysis from media can bring the reader to a place beyond the surface. The media use of the term, “cult” is “something which looks like our religion but is not.” Many ‘Providence movements’ have been caught up in media scandals. This morning I was reading on my ABC News updates the scandal of Paul Nthenge Mackenzie and his Good News International Church (2003-2019) in eastern Kenya. The details of deaths and starvation are horrible but not the main point. At the centre of the media reports is the personal psychology of ‘The Leader” and “The Followers”. I believe this abstraction is correct in the media reporting, but, as journalism, it remains at the surface level or layer. The analysis is a challenge for all Christians, but it also a challenge for Post-Christians and anyone who wishes to retain western thinking. I do. These ‘cults’ uses the language of ‘Jesus’ in references to leading, following, as well as of disciples. The language is very problematic as it appears in evangelicalism, secular Christianity, cultural Christianity (meaning having knowledge of ‘culture’, but not theology), and possibly elsewhere. For millennium, theology has wrestled with the literalism of such claims, where ‘God’, ‘Jesus’ and ‘discipleship’ become mechanisms of control. Neo-Evangelicalism has performed a wonderful ‘shell game’ in the Janus Face Game (refer to Habermas literature 1991-2010 and critical examination of Janus-Face concept in Lenscheu-Jey Lee 2022 and Salvatore 2017). Here the evangelical bubble thinking has yet to confront the deep critique of the Habermasian theme which is hidden in the evangelical shell game; if such historians, sociologists, and philosophers are gamed enough to wrestle with the constructed historiography.

However, there are another layer here for evangelical believers and me. The engagement of the Saturday 2023 EHA conference, and contemplating the “aftermath of evangelicalism” (‘aftermath’: a term to arise from the conference discussion/papers as a ‘after-life’), brought me to the second revelatory moment in my life; one post-Ruth. The first was that moment in 1995 for both Ruth and I, for different reasons which overlapped. Without Ruth now, I have become bolder in my scholarship. It is a new life without overtaxing Ruth with unpaid boldness and a liability to institutions if my critical thinking achieved any popularity. The abstract is never reduced to personal psychology, but the personal psychology (dispositional states of being) speaks everything to the decisions we make in life’s journey once the abstraction is realised. I have come to realise the view from outside my own personal bubble: the revelatory moment. I am intense, and overwhelming. I tend to do things intensely and in such an overwhelming style. Take for instance, my celebration last night (Saturday) with a five-course meal and five selected wines at a very expensive restaurant.[1] It might be seen as a personal weakness, but it has great abstract strength. Jesus was intense, and overwhelming. Don’t worry, I renounce all pathways into a totalitarian Jesusism (an example is a recent film; and speaks to me on how my evangelical youth shaped me as an intense and overwhelming person). I am not Jesus, nor a son of God. I am an open and compatibilist scholar who is honest on where the conflict truly lies, and not in the nonsense apologetics.

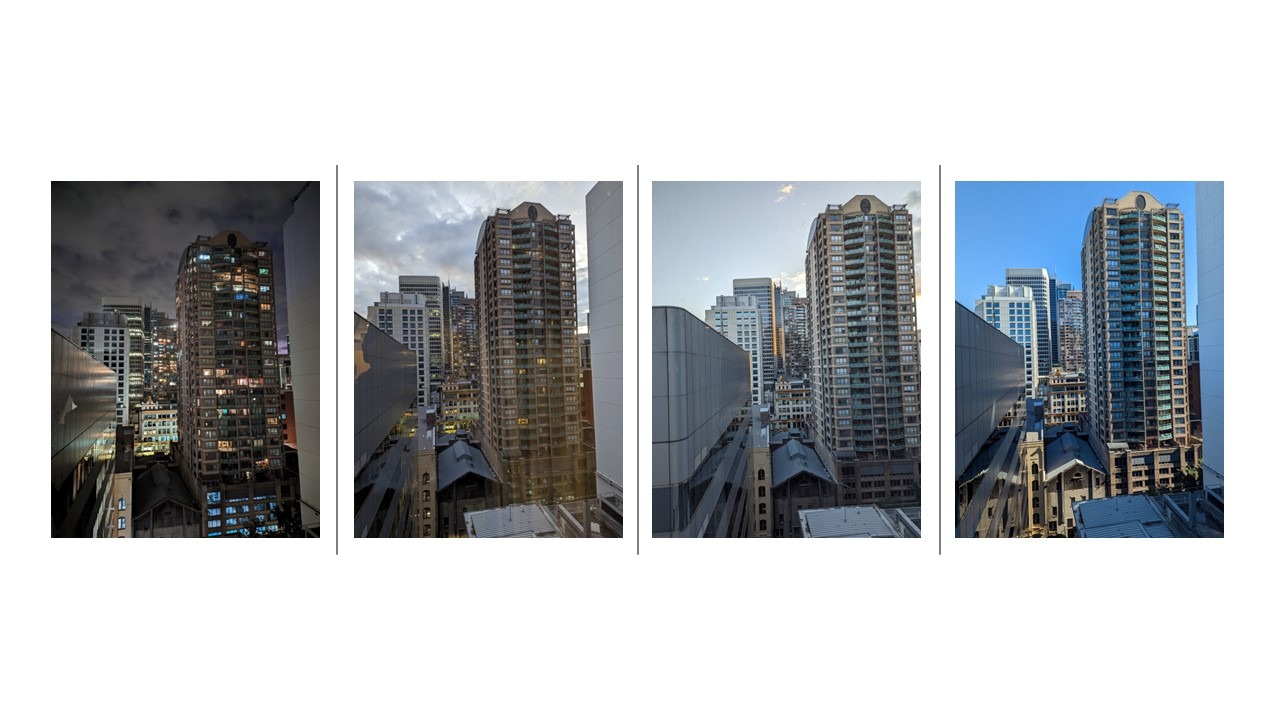

Image: Dining at Cirrus, at Barangaroo on the Darling Harbour, Sydney. See footnote 1.

However, to be clear: my criticism is not an attack on evangelical believers, personally, nor criticising on the right for evangelicals to hold their orthodox beliefs. Yes, I am rejecting orthodoxies (continually; meaning I reject pre-set ‘correct beliefs’ as abstractly defined and faithfully unchanging in face of the shifting historical conditions). I do not, though, expect anyone to shift from their ‘fundamental’ or basic beliefs. What I do expect is a freedom to get beyond orthodoxies. And this idea returns the discussion to the bland evangelic reference of “non-providential” and alternatives which might present themselves.

Featured Image: 2023-05-20 Neville, at Cirrus, Barangaroo, Darling Harbour, Sydney.

In a similar style of Cupitt’s view of the everyday (speech), Wayne Hudson’s (2004, 2005) discussion of the mundane, non-mundane, and anti-mundane has important bearing, and it develops the ethics layer of the discussion. Hudson frames the ideas in the Feuerbachian Project which led to Cupitt’s non-providential framing in the ‘Death of God’ movement.

“…Feuerbach admitted that the representation of feeling in religious consciousness produced the most fundamental access of the human being to knowledge of its own species nature. That fact that for Feuerbach the object of religion was understood to be primarily an object of feeling did not mean that religion was unimportant. On the contrary, Feuerbach recognised that the human essence needed to be objectified in an alienated form before it could be returned to the human being in a corrected and developed form. To this extent, the happy fault of Christian theology survived in Feuerbach’s atheistic humanism, and Feuerbach’s famous claim that God was only a projection of the deepest dimension of human subjectivity had the radical implication that it might be necessary to make this projection before human beings could recognise their own non-mundane being for the first time.” (Hudson 2005: 6-7; I emphasis the word)

The ideas of the mundane, non-mundane, and anti-mundane means Christian ethics, which is in actuality, authentic experience, existential, is mundane but heighten in the language of wonder, immanent introspection, and transcendent-oriented belief. The non-mundane is a Kantian abstract sense of the noumena, removed from the mundane phenomena. This then is the only way that evangelical believers can make sense of the orthodox messages from their biblicism framework. The messages are abstractions but also the inscrutable[2] ways of God. Several times at the 2023 EHA conference, I heard this phrase said: “God’s ways are inscrutable.” Here evangelicalism has a big problem if the shell game is revealed, not as Stephen Jay Gould’s “non-overlapping magisteria,” but as a mundane magic trick we have seen many times before and well-explained. Kantian abstractions can remain after the Feuerbachian Project, but magic thinking cannot; and not if evangelicalism continues to seek academic legitimatisation in modern/postmodern scholarship. Evangelical believers can have their cake of personal belief. And they can eat their cake through rigorous analysis and modern/postmodern forms of synthesis. But they can not have the cake and eat it.

Image: 2023-05-19 Recovery at the Ibis Sydney.

I have personally reached my state of a Recovery Moment; this Sunday afternoon from the writing. A decision is to be made. And I decide to continue my critical work in evangelical historiography (the cake), but deepening my work beyond an analysis of the bubble thinking (eating cake). The short-term movement beyond will be in the important work of Habermas. In that, I believe I personally can have the cake and eat it.

Image: 2023-05-21 View from Room 1416, Ibis Styles Sydney Central. Recovery Moment.

REFERENCES

Bebbington, David W. (1989). Evangelicalism in Modern Britain: A History from the 1730s to the 1980s, London: Unwin Hyman.

Cupitt, Don (2000). Solar Ethics, SCM Press.

Cupitt, Don (2008). The Meaning of the West: An Apologia for Secular Christianity, SCM Press.

Cupitt, Don (2009). Jesus and Philosophy, SCM Press.

Cupitt, Don (2011). Meaning of It All in Everyday Speech, SCM Press.

Freundlieb, Dieter and Wayne Hudson, John F. Rundell (2004). Critical Theory after Habermas. Brill, Leiden ; Boston.

Habermas, Jürgen (1991). The Theory of Communicative Action : Lifeworld and Systems, a Critique of Functionalist Reason, Volume 2, Polity Press.

Habermas, Jürgen (1992). Communication and the Evolution of Society, Polity Press.

Habermas, Jürgen (1997). Between Facts and Norms: Contributions to a Discourse Theory of Law and Democracy, Polity Press.

Habermas, Jürgen (1991). Knowledge and Human Interests, Polity Press.

Habermas, Jürgen (2010). Legitimation Crisis, Polity Press.

Hudson, Wayne (1997). Constructivism and history teaching. Griffith University, Brisbane, Qld.

Hudson, Wayne (2004). Postreligious Aesthetics and Critical Theory, in Critical Theory after Habermas [listed above], 133-154.

Hudson, Wayne (2005). The Enlightenment Critique of ‘Religion’, Australian EJournal of Theology, (5), 1-13.

Hudson, Wayne (2016). Australian Religious Thought, Monash University Publishing.

Lenscheu-Jey Lee (2022). Examining The Janus Face Of Power In Critical Literacy Through A Habermasian Lens, International Journal of Critical Pedagogy, 12:1, 126-138.

Salvatore, Italia (2017). A Janus-faced Approach to Learning: A Critical Discussion of Habermas’ Pragmatic Approach, Journal of Philosophy of Education, 51:2, 443–460.

Spector, Matthew (2010). Habermas: an intellectual biography, Cambridge University Press.

[1] Cirrus, at Barangaroo on the Darling Harbour, Sydney. The pre-dinner drink was a New York sour. It grew on me. Unsure with the first few sips. But really enjoyed the last few sip. First course, bread and a scallop with an Italian Brut. The scallop was incredible. Second course, Kingfish followed by The Prawn, all with a German Riesling. Third course, Barramundi with veggies and a very dry Italian white from the Venice region. Fourth course, a steak with a very tasty chips, an Italian red from the Alba region. Final course, dessert! Yoghurt, White Chocolate, Macadamia and Passionfruit. And a German dessert wine. The price: $264.32, overwhelming for uno me. Nevertheless, there was, as the evangelicals say, testimony during the ostentatious* dining experience, a wonderful conversation with a young couple at the next table. They had recently came from Denmark and settled in Sydney (but not Danish). We talked about Brisbane and life. Apart of that conversation was on the topic of religion, spirituality, and personal belief. It is a personal experience which leads me to think that most persons will never find themselves in the scoping of evangelicalism. Evangelicalism understands this point in the rhetoric of the narrow pathway in Jesus Christ, but the modern evangelical outlook contradicts itself in the push for accommodation for modernist (post) schemas; even fundamentalists are ignorantly caught up in that movement to some (smaller) principled degree. I am sure my couple at the next table found me overwhelming (to some degree), however, there was kindness in the way they listen to me, and I with them. *NB. ostentatious: attracting or seeking to attract attention, admiration, or envy often by gaudiness or obviousness; overly elaborate or conspicuous; characterized by, fond of, or evincing ostentation; an ostentatious display of wealth/knowledge.

[2] Inscrutable: impossible to understand or interpret.

Neville Buch

Latest posts by Neville Buch (see all)

- Dear grossly, ethically, corrupted - December 21, 2024

- Thoughts with a Professional History colleague on “Artificial Intelligence” - December 21, 2024

- Stephanie M. Lee on “AI by omission”, The Chronicle of Higher Education, Thursday, December 19, 2024 - December 20, 2024